To date, scholarly and popular histories of the Mongols have been dominated by the seemingly masculine topic of Mongol warfare, which makes it easy to suspect that steppe women enjoyed little political, social, or economic power. Furthermore, Mongol society before Chinggis Khan’s rise was not only impoverished but also tremendously unsettled, so that nomadic women were vulnerable to aggression, violence, and rape. This may especially have been the case among rank-and-file nomadic subjects, among whom harsh circumstances might weigh more heavily on women and girls than on men and boys.Footnote 1 Nevertheless, despite the dangers inherent in their society, many nomadic women enjoyed control and exerted influence in a wide range of arenas. As for women at the pinnacle of steppe society, such as the Chinggisids, the picture is one of wealth, responsibility and tremendous opportunity for those with intelligence and talent.

It is only possible to appreciate the authority that some women enjoyed and the contributions they made to Mongol history if we understand the general situation of women on the steppe. To do this, we must examine their lives in detail. We begin with marriage, since women’s most extensive powers tended to appear after marriage through their status as wives, mothers, or widows. Next comes women’s work, since they engaged all day long in a wide range of activities, which required the formation and maintenance of many complex relationships. Along with work, we must investigate women’s economic opportunities, since their daily business included the management, control, and exploitation of animal, human, and other resources. An additional area of women’s activity centered on hospitality and religious duties. Women also had a profound influence on the family: in the immediate sphere, they managed the upbringing of children with the help of others, while on a larger front, women were essential to the question of succession and inheritance, since a woman’s own status shaped the options open to her children. Women also figured in politics in many ways, including as advisors to others, as political actors themselves, or as the critical links that joined allied families, among other roles. Finally, women’s private, interior lives came to affect the empire in surprising ways, especially those conquered women brought into the Chinggisid house by force, whose loyalty to that house was never questioned, but perhaps should have been.

It is also necessary to remember that all women’s lives were governed by status. Steppe society remained generally hierarchical in nature for women and men, even after Chinggis Khan upended existing social hierarchies to create a new, merit-based social and military system. We cannot understand the activities of women, and from them learn about their relationships and their control of resources, without locating these women in a hierarchy of rank of which nomads themselves were exquisitely aware.

Bride Price, Levirate, and Seniority among Wives

Although the Mongols were a polygynous people, wealth strongly shaped marriage, since rich men wedded more wives than poor ones.Footnote 2 One reason was that Mongol grooms paid a bride price to compensate a prospective wife’s family for the “loss” of their daughter.Footnote 3 Brides with wealthy parents could bring a dowry (inje) of household items, jewelry, livestock, and even servants and slaves to the union. But this was not always produced immediately – in some cases the delay could be as long as three years – and in any case seems to have been less than the sum provided by the groom.Footnote 4 Furthermore, when the dowry did appear it remained the woman’s personal property, not the man’s, and later went to her children: livestock to sons, cloth and jewels to daughters, and servants to both.Footnote 5 If a family could not afford a bride price, the groom might instead pay off his debt by working for his father-in-law for a period of time. Another option was to arrange a double marriage between two families, where each family provided a son and a daughter, which allowed both sides to dispense with bride price.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, for poorer men in the chaotic period before Temüjin’s rise, the bride price may have been such a barrier to marriage, and the idea of labor so unappealing, that one affordable way to acquire a wife became to kidnap her, even though this eliminated any chance of a dowry.Footnote 7 Thus one scholar has suggested that Temüjin’s father, Yisügei, was himself relatively poor, first because he acquired Temüjin’s mother, Hö’elün, by kidnapping her, not by negotiating an agreement with her parents; and second because he left their son Temüjin to work off the bride price for his fiancée, Börte, rather than simply providing the expected gift.Footnote 8

The Mongols engaged in strictly exogamous marriages, which stipulated that individuals had to wed into a lineage other than their own.Footnote 9 Nomadic society was organized by larger groups (oboq, sometimes “tribes”Footnote 10) descended from a real or mythical ancestor, and within these large groups, by smaller patrilineal descent groups (uruq), or lineages. One large group could contain multiple lineages, usually connected to one another by a cousinly relationship.Footnote 11 Marriages between descendants of related patrilineal groups were unacceptable, but loopholes did exist. In particular, the Mongols favored exchange marriages, where children married back into their mother’s natal line. This could be a daughter marrying her mother’s nephew “in exchange” for the mother’s earlier marriage, or it could be a sister exchange, where a son and his male cousin married one another’s sisters.Footnote 12 Such marriages were possible within the rules of exogamy because of the patrilineal quality of nomadic lineages, which meant that the bloodlines of fathers, not mothers, determined the relationship between two prospective partners.Footnote 13 Thus a couple could marry their daughter or son to the mother’s nephew or niece without qualm, since the fathers in question – the man, his wife’s brother – were not related by blood. By modern standards these marriages would be consanguineous on the mother’s side, but this was not a concern for the Mongols.Footnote 14 Although consanguinity may have contributed to the poor health that plagued the Chinggisids in the later decades of their empire, it should not be seen as the sole cause.Footnote 15

Although details on the negotiation process are scant for the early period, mothers are likely to have been actively involved in pairing their own children with those of their siblings. Certainly mothers shaped their children’s marital futures through the preference for the woman’s relatives as partners. It is reasonable to assume that women were also somehow involved in the negotiations for their children, especially since later marriage manuals point to the active participation of both sets of parents in the wedding ceremonies.Footnote 16 Fathers and mothers together might accompany their daughters to their new homes after the wedding.Footnote 17

If a woman’s husband died, the widow usually engaged in a second, levirate marriage to a junior kinsman of her deceased husband, such as a younger brother, nephew, or son from another wife.Footnote 18 Levirate marriage gave the widow a protector, and kept her from seeking remarriage outside the husband’s family, taking his children and any property she controlled with her.Footnote 19 Despite the levirate’s origin as a nomadic practice, it later appeared in the Mongol Empire among subject peoples as well, even though at times it conflicted with existing, non-Mongol legal practices.Footnote 20 But although levirate marriage was widespread on the steppe, a few imperial widows of Chinggisid princes managed to avoid remarriage, and thus formed one important exception to this rule.Footnote 21

Scholars have claimed that wealthy men with many wives treated their wives equally.Footnote 22 Even if this delightful theory were possible to carry out, it did not mean that wives were equal to one another in status. Rather, nomadic society distinguished clearly between wives according to rank, even though all wives had their own dwelling, servants, income, and husbandly attention. The senior wife was the most important, and was often the first woman the husband married. She controlled the largest and wealthiest camp (ordo). At the same time, a few other high-status wives controlled secondary camps. The junior wives and concubines then lived in the establishments of either the senior wife or the lesser camp-managing wives and answered to them.Footnote 23 A senior wife could be displaced if she had no children or died, in which case another woman would become the next senior wife through marriage and the bestowal of the senior wife’s camp on her. If the second senior woman had been a junior wife, a reassignment of the main camp might take place; if she already had her own camp, she would simply increase in honors, respect, and ceremonial to reflect her new status.Footnote 24 Historical sources from China suggest that each Mongol khan had four main wives with four main camps, but sources for the Western Khanates beginning in the mid-thirteenth century do not always specify a fixed number of camps.Footnote 25 Spatially, wifely dwellings within each camp formed a line arranged in strict hierarchy of rank, with the managing wife at the westernmost position, and the most junior wife at the eastern end.Footnote 26 Younger children lived with their mother, older children had their own gers (yurts, or round, felt-walled tents) behind her, and servants inhabited lesser quarters behind the family they served.Footnote 27 (Concubines were also positioned behind the wives, but in front of the gers of the bodyguard and officials.Footnote 28) We may assume that when several camp-managing wives were together, the camps were lined up in order of the status of the mistresses. Once the Chinggisids had established their empire, all of the imperial gers became marvels of gleaming white felt outside and gold brocade inside, strewn with carpets and decorated with gems and pearls to mark the imperial status of the inhabitants.Footnote 29 The khan may have possessed his own establishment, and also a larger pavilion, which held the thrones for him and his senior wife.Footnote 30 But for daily living, the husband appears to have moved from ger to ger among his wives, accompanied by his guards (keshig).Footnote 31 Additional guards were responsible for the safety of the entire family compound, which was further protected by lines of carts, and an open space in front of the imperial gers.Footnote 32 Above and beyond the imperial guard, some women may have had their own guardsmen, although in smaller numbers than the keshig.Footnote 33

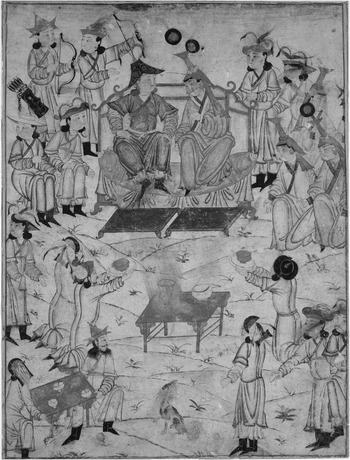

In addition to holding the most prestigious place in the wifely line, the senior wife spent more time with the husband than did the junior wives, which may explain why senior wives often had many children (between five and nine), whereas junior wives and concubines tended to have one or two.Footnote 34 Although a junior wife enjoyed precedence over her co-wives during drinking-parties at her dwelling if her husband attended, otherwise the senior wife sat closest to the husband at ceremonies and receptions, and received other courtesies: at feasts in thirteenth-century Yuan China, for example, Qubilai (r. 1260–94) sat at a raised table with his senior wife, while the junior wives sat at a lower table so that their heads were level with the senior wife’s feet.Footnote 35 (See Figure 1.1.) In the royal encampments of the Jochid khanate along the Volga River, the khan’s throne had space for two – the khan and the senior wife – and was situated on a platform raised three steps off the floor.Footnote 36 Less vertical yet equally telling ceremonial distinctions appeared during fourteenth-century Jochid social gatherings, where the khan walked to the doorway of an imperial pavilion to welcome his senior wife and seat her. He then met the junior wives in order after they had entered the pavilion, not at the doorway.Footnote 37 On the grimmer end of womanly duties in the steppe, widows in general and certainly senior widows in particular usually survived their husbands’ funerals, whereas concubines could be dispatched – by strangulation, immolation, or live burial – to serve their master in the afterlife, along with male servants and livestock. Although wives were expected to rejoin their husband after death, they generally escaped being sent after him immediately, since duties to their live children, and to their new husband if they remarried through the levirate, outweighed duties to their dead spouse for the time being.Footnote 38

Figure 1.1 An enthronement scene from the Diez Albums, Iran (possibly Tabriz), early fourteenth century, ink, colors, and gold on paper. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin-Prussischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung, Diez Album, fol. 70, S. 22.

Women and Work

We can best imagine steppe women’s lives by examining the work they did every day.Footnote 39 The Franciscan Friar Carpini, who traveled through the Mongol Empire in 1245–7, and his later counterpart, Friar William of Rubruck in 1253–5, both noted that women’s responsibilities were extensive.Footnote 40 Friar William in particular catalogued the separate duties of women and men: men made gers and wagons, but women managed the journeys between summer and winter camps by loading the gers on to the wagons, driving the wagons to the next site, and unloading them again.Footnote 41 Gender similarly shaped livestock duties: women cared for cattle, men tended horses and camels, and both took care of sheep and goats. In addition, men fermented mares’ milk (qumiz), fashioned weapons and tack, and cured skins; women made butter, cooked, and sewed clothes from the skins the men had cured.Footnote 42 As one scholar puts it, women handled all work relating to the hearth, to dairy production except from horses, and to childrearing (which will be discussed later); men handled hunting, fighting, and horses; and both cooperated to manage small animals, make felt, and preserve meat at butchering time.Footnote 43 The interiors of Mongol dwellings reflected the clear division of labor, with different sections designated for men and women, the tools they needed, and specific kinds of work.Footnote 44

But Friar William’s otherwise useful description overlooks both the way a woman’s status determined her labor, and the question of overall management, which was the responsibility of wives in general and a senior wife in particular. Women maintained their camps both when men were present, and when they departed to hunt or fight, which they did regularly.Footnote 45 These were non-combatant camps (a’ughruq / a’uruq, sometimes called ordo as well).Footnote 46 Whenever the man was absent from the non-combatant camp, the senior wife supervised everything.Footnote 47 During military campaigns, a different kind of camp (potentially and confusingly also called ordo),Footnote 48 was also run by a woman with staff, but these accompanied the armies as they traveled.Footnote 49 When Chinggis Khan set out on his conquests, he took one wife with him to manage the traveling camp, while the other wives remained in Mongolia to manage the non-combatant camps.Footnote 50 In addition to this routine management, some wives took on extra responsibilities temporarily or even permanently if their husbands died.Footnote 51

The writings of the fourteenth-century Muslim North African visitor to the Mongols, Ibn Baṭūṭah (d. 1377), reveal further details of the labor of imperial women (khatuns, “ladies” or “queens”), gained when he met the wives and married daughter of the Jochid ruler Özbek Khan (r. 1313–41) in the grasslands near the Volga River.Footnote 52 Like Friar William, Ibn Baṭṭuṭah described royal women as they engaged in domestic activities, but unlike Friar William, he mentioned their managerial roles. Thus when Özbek’s senior wife received Ibn Baṭṭuṭah, she was both personally cleaning a tray of cherries, and overseeing fifty female servants doing the same. Similarly, whereas Friar William suggested that all women sewed clothes, Ibn Baṭṭuṭah instead found another royal wife reading aloud to thirty ladies as they performed skilled embroidery for her.Footnote 53

In the case of the wives of Chinggisid princes, the question of management became further complicated by the presence of the imperial bodyguards (keshig) after 1203.Footnote 54 A certain number of the guards were responsible for important household tasks that overlapped the wifely domain. Guards supervised some male and female household attendants, managed the care of some animals, maintained weapons, carts, and hunting equipment; supplied, staffed, and ran the kitchens, and helped distribute certain kinds of spoils.Footnote 55 Although clearly some of these responsibilities related to their military duties, others, especially food preparation, intertwined with women’s work. Officers in the keshig appear to have answered both to the Chinggisid prince they guarded, and to the wife in whose camp they were assigned. For example, the Tangut Buda, who was a commander of a hundred in Chinggis Khan’s personal unit of a thousand, reported militarily to Chinggis Khan, and domestically to his senior wife, Börte, as her personal camp commander (amīr-i ordo in later sources). The position of camp commander in an imperial woman’s establishment became standard in the decades after Chinggis Khan.Footnote 56 Wives were responsible not only for working with the camp commander, but also for coordinating additional areas of activity that were not under the camp commander’s purview, such as some animal care, children’s needs, clothing and wardrobe, religious rituals like the mourning of the dead, trade and political advice (both of which will be discussed later). In addition to the camp commander, a set of male and female administrative officers reported to each imperial wife and helped manage her retinue.Footnote 57 The activities, equipment, and personnel a woman and her staff had to supervise could be extensive, as shown in a financial decision made by Ghazan (r. 1295–1304) in the Ilkhanate: “funds for the ladies’ board, provisions, necessities of wardrobes and mounts would be assured, as would be funds for supplies for the department of potables and stables, for camels and pack horses, and for wages of maids, eunuchs, custodians, kitchen help, caravan drivers, muleteers, and other servants and retinue [of each lady] as necessary.”Footnote 58 Even concubines formed part of the domestic work force: Marco Polo remarks that concubines on duty at Qubilai’s court not only had sex with Qubilai, but also prepared and served food and drink. At the same time, other women spent their time sewing or “cut[ting] out gloves and … other genteel work.”Footnote 59

According to Friar William, one imperial woman might possess 200 wagons of belongings, as well as servants to tend to them.Footnote 60 Indeed, one of Chinggis Khan’s secondary wives, the Kereit princess Ibaqa, came into the marriage with at least 200 servants and 2 stewards (and the corresponding wagons), as well as slaves and followers, horses and cattle, and equipment and stores that included golden dishes.Footnote 61 Later the Jochid prince Sartaq (r. 1257) married 6 wives, whose wagons numbered 1,200 when gathered together.Footnote 62 In China under Qubilai, each of the 4 most important wives had her own dwelling and 300 ladies-in-waiting, male and female servants, and staff to help her manage all this, so that each establishment might number as many as 10,000 people.Footnote 63 In the fourteenth century Volga grasslands, each of Özbek’s wives attended Friday court ceremonies with 370 attendants.Footnote 64 When Özbek’s third wife, a Byzantine princess, returned to Constantinople to give birth, she took a retinue of about 500 people (servants and troops), 400 wagons, 2,000 horses, and 500 oxen and camels. Not only was this merely a fraction of her own people, but it did not even include the 5,000 additional warriors her husband sent to escort her.Footnote 65 In addition to their immediate retinues, some women controlled peoples given to them as spoils, such as the 3,000 Olqunu’ut subjects that Chinggis Khan gave to his mother, Hö’elün, in 1206, or the Tanguts he bestowed on his wife Yisüi during his final campaign in 1226–7.Footnote 66 Women’s subjects, dependents and retinues could therefore be numerous, especially among women in the ruling elite. Some visitors to the Mongols were astonished to reach settlements as large as cities, whose inhabitants were mostly female; these were the establishments of imperial women.Footnote 67 When a Chinese visitor arrived at Chinggis Khan’s home camp in summer 1221, he found an enormous moveable city – “hundreds and thousands of wagons and tents.”Footnote 68 This was managed by the highest-ranking wife, the Empress (possibly Börte) while Chinggis Khan was campaigning thousands of miles to the west, based in a traveling camp run by his junior wife Qulan.Footnote 69 Indeed, nomadic men were free to specialize in warfare to such a high degree precisely because nomadic women managed camps with such skill.

Economics, Hospitality, and Religion

Given women’s extensive control of animal, human, and other resources, it comes as no surprise that they were economically important to the families into which they married. Any aristocratic wife acquired through negotiation (not kidnap or capture) had her dowry in livestock, cloth, jewels, household items, and servants. A senior wife also received a portion of her husband’s wealth after marriage, often in livestock, which she managed for him during his lifetime and held after his death for their youngest son to inherit.Footnote 70 (Junior wives also held part of their husband’s wealth, but the amounts relative to the share of the senior wife are unknown.)Footnote 71 Thus when a woman emerged from her ger every morning she might gaze on both her own animals and those of her husband; it is probable that she kept close track of which animals were whose over generations of livestock. Women could also employ Muslim, Chinese, or other merchants (ortaqs) to act as financial agents and engage in sales, purchases, or investments with capital that the woman supplied. Such merchants furnished women with interest, profits from enterprises, and gifts from third parties.Footnote 72 Even as the empire was forming, personal merchants soon became standard among imperial wives.Footnote 73 Thus, for example, in 1218 Chinggis Khan ordered all the princesses, princes, and major commanders to send agents with ingots of precious metal to trade in the Khwarazm-Shah Empire.Footnote 74

But other than the dowry, the husbandly grant, and the potentially shrewd uses to which women put these assets, women did not receive a regular income from men.Footnote 75 Instead men provided occasional gifts in the form of spoils from warfare by distributing goods, animals, territories, and peoples both to male followers, and also to wives, mother, sisters, and daughters, not to mention stepmothers, aunts, and daughters-in-law. After Chinggis Khan conquered Northern China, for example, he gave all his wives lands there, which became their own possessions, not his.Footnote 76 Similarly in 1219 he parceled out artisans captured at Samarqand to “officers, commanders and ladies.”Footnote 77 At the quriltais where Grand Khans were elected, the princesses, princes, generals, and administrators were rewarded by the new ruler with handsome gifts.Footnote 78 Once the Mongol Empire was established, wives of rulers could expect to receive gifts from subject rulers or their envoys, or from ministers and officials working directly for the Chinggisids.Footnote 79 In later decades, imperial women acquired access to tax monies raised from conquered populations.Footnote 80 Overall this meant that the female kin of a steppe leader could control herds, deposits of ore or other natural resources, artisans and craftspeople, and even portions of industries.Footnote 81

Yet a wife’s duties hardly stopped with the practical matters of managing personnel and exploiting resources. According to a maxim attributed to Chinggis Khan, a wife bore the weighty responsibility of promoting her husband’s public reputation by maintaining the hospitality of their home for guests, especially when the husband himself was away.Footnote 82 Thus in the case of the Chinese visitor to Mongolia in 1221, the Empress chose her guest’s lodging site within the great camp and demonstrated her hospitality by sending him melted butter and clotted milk every day, while her co-wives, the Jin and Tangut princesses, dispatched gifts of clothing, millet, and cash (silver).Footnote 83 Similarly in 1246 it was the wives of the new Grand Khan Güyük (r. 1246–8) who arranged a welcome for Friar Carpini and his companions when they arrived at the imperial camp.Footnote 84 Social status and rank further shaped hospitality, just as it did the rest of Mongol society. Thus, when in 1254 Friar William paid calls on Möngke’s family, he first met with Möngke and his senior wife in her personal gold-hung ger, went next to Möngke’s oldest son, and then called on Möngke’s other wives and daughter in order by rank.Footnote 85 Ibn Baṭṭuṭah similarly took careful note of seniority while paying his respects to Özbek’s wives and daughter in the 1330s.Footnote 86 During such visits, wives could favor individuals by giving them bowls of qumiz with their own hands, or sitting and looking on while they ate; by contrast, less privileged guests were waited on by servants.Footnote 87

Imperial women also acted as participants in and patrons of religion, whether shamanism, Taoism, Nestorian Christianity, Islam, Tibetan Buddhism, or a combination of several.Footnote 88 Women learned not only to practice religion but participate in religious ceremonies, and sometimes preside over them.Footnote 89 Some imperial women were known for the portable houses of worship that accompanied them everywhere, while others patronized a range of religions financially.Footnote 90 Imperial hostesses also facilitated religious events, as seen in the example of Özbek’s daughter, who summoned the Muslim personnel in the camp so that Ibn Baṭṭuṭah and his companions could meet them. Similarly the senior wife of Grand Khan Möngke (r. 1251–9) attended Christian services, then hosted a meal that Friar William attended.Footnote 91

Thus it is clear that although in a very small household a woman’s duties might not exceed the activities that Friar William described, in larger establishments women had to oversee the coordination of significant resources (herds, flocks, subjects) as well as people (shepherds, stewards, craftspeople, household servants, and armed retainers). It is surely no accident that another of Chinggis Khan’s maxims described an ideal steppe girl as not only naturally beautiful without “combs or rouge,” but also spry and efficient.Footnote 92 Friar Carpini claimed that the reality matched Chinggis Khan’s ideal: “In all their tasks they [the women] are very swift and energetic.”Footnote 93 To keep up with their many responsibilities, they would have to be.

Women, Children, Inheritance, and Succession

In addition to the work they performed on a daily basis, women in general and mothers in particular had the potential to shape steppe society through childbearing, childrearing, and inheritance. Although mothers played a central role in bringing up children, childrearing was a joint endeavor shared by all adults.Footnote 94 This communal approach was strengthened by existing practices: some mothers sent their children out for extended visits with other branches of the family, while in all cases women with the means to do so employed wet nurses and attendants when children stayed at home.Footnote 95 Later during the independent khanates, tutors and religious officials taught the royal young, along with co-wives and others.Footnote 96 To gain a better understanding of childrearing in the Mongol period, scholars have combined a modern anthropological approach with careful mining of the historical sources to propose the following: young people seem to have been taught to have a sense of honor, a respect for hierarchy, admiration for elders, and an appreciation for working with others.Footnote 97 Children were also encouraged to develop a certain “agility of spirit.”Footnote 98 This could be achieved through games like chess, which taught strategy; or riddles, which were fun and also helped children learn to use metaphors and metonyms in place of taboo objects (See Figure 1.2).Footnote 99 Literature was oral among the Mongols at least until they acquired a script in the 12-aughts thus children not only memorized existing maxims, songs, stories, and epics, but were encouraged to produce new pieces extemporaneously, since the ability to create literature on the spot as occasion demanded was highly valued in steppe society.Footnote 100 Children furthermore learned rules, practical advice, and genealogy, which helped them follow the regulations of exogamous marriage.Footnote 101 In addition to these abstract forms of knowledge, children learned how to care for specific animals – goats, sheep, horses, cattle, camels – at specific ages as they themselves matured.Footnote 102

To date, scholars have focused on the way mothers interacted with sons: they have noted that nomadic society expected women to promote peace and cooperation among their boys, and, when the mothers were high in status, rear their sons to be leaders.Footnote 103 One mother in Chinggis Khan’s family was celebrated by contemporary authors and modern scholars alike for the way she taught her four sons Mongol customs, beliefs, and military practices, as well as the religions, beliefs, and habits of the sedentary peoples they controlled.Footnote 104 Certain mothers within the Mongol empire themselves held great political importance: Chinggis Khan’s mother, Hö’elün, helped her oldest son establish himself, while others were instrumental in maneuvering their sons onto a throne they should not have held at all.Footnote 105

In literature, including The Secret History of the Mongols,Footnote 106 mothers appear as responsible for harnessing the tremendous violence expected of males in Mongol society, and directing their sons’ aggression outward against enemies, not against one another. The most famous example of such a portrayal was the ancestral Mongol mother, Alan-qo’a, who appeared in the Secret History using the example of individual arrows versus arrows tied together to teach her sons that cooperation would make them a force to be reckoned with: “If, like the five arrow-shafts just now, each of you keeps to himself, then, like those single arrow-shafts, anybody will easily break you. If, like the bound arrow-shafts, you remain together and of one mind, how can anyone deal with you so easily?”Footnote 107 Scholars caution us to view such stories of mothers and sons as folkloric motifs designed to teach lessons about the high costs of disunity among brothers, not as historical reality.Footnote 108 Nevertheless, such stories at least indicate that the author and audience of the Secret History were likely to see women as appropriate teachers on moral questions like proper sibling behavior. A later historian, writing without the arrow motif, described another woman in a similar vein: “she exerted herself to raise and educate them [her sons] and teach them skills and manners. She never allowed even an iota of disagreement to come between them.”Footnote 109

But scholars of the Mongol empire have paid little attention to the upbringing of girls.Footnote 110 Surely, however, steppe women worked as hard at raising their daughters as they did at everything else, since the competent wives, mothers, and widows who crowd Mongol history did not come from nowhere. A close look at the historical sources reveals that traces of their education can indeed be found. Thus Friar William observed women making and breaking camp, driving, cooking, sewing clothes, and tending animals, from which we may deduce that girls learned these activities when young.Footnote 111 Since many historical observers saw women riding and shooting, it is logical to assume that girls acquired these skills, too, probably with instruction given the danger involved for a novice – Friar Carpini notes that children began to ride at the age of two or three.Footnote 112 If we accept Chinggis Khan’s maxim on a wife’s duty to provide good hospitality, then we may infer that girls were taught about the proper reception of guests.Footnote 113 If we observe that most senior wives used a range of techniques to manage their people, herds, and property – possibly including memorizing their animals’ strengths, weaknesses, and bloodlinesFootnote 114 – then it is reasonable to conjecture that women began to acquire management skills as girls, and further that they probably passed them on to their daughters.Footnote 115 The ample evidence we see of women’s religious involvement similarly indicates that girls learned to participate in shamanistic ceremonies and rituals, or those of other religions.Footnote 116 In addition, politically successful women had husbands who listened to their advice and rewarded them for it with spoils; they must have figured out how best to advise others, as when Chinggis Khan’s Tatar wife Yisügen convinced him to look for her sister and marry her, and when the sister, Yisüi, later persuaded him to make a partial reconstitution of his Tatar enemies.Footnote 117

Another arena in which women played a critical role was that of inheritance, especially succession to a throne. On the steppe, succession was a complex, contrary, and contradictory process: a ruler could be followed by a senior male member of his family (uncles, brothers), a son, grandson or nephew that he chose himself (ruler’s choice), or a widow acting as regent for a son.Footnote 118 Or the next ruler could be his oldest son (primogeniture) or his youngest (ultimogeniture), as long as their mother was his senior wife – sons of junior wives were not candidates for succession.Footnote 119 But Chinggis Khan narrowed the options for succession to his empire by limiting himself to the four sons of his senior wife, Börte, and cutting out his brothers, uncles, and nephews, as well as his sons from junior wives. His descendants similarly preferred their offspring as heirs. Thus whereas the senior wife of any steppe leader knew her sons might inherit rule from their father but had competition from other men in the family, the senior wife of a Chinggisid knew her sons’ chances were much better because succession was so limited.Footnote 120

As for daughters: these often married their father’s political allies or vassals.Footnote 121 One theory is that the great nomadic empires that preceded the Mongols were confederations of various peoples led by rulers who maintained their alliances chiefly through marriage ties.Footnote 122 Although Chinggis Khan is widely credited with dismantling the confederation system, he did actually make confederation-style marriages himself, as seen in Chapter 4. It should come as no surprise that the most important of these alliances were reserved for children of his senior wife. Börte’s five daughters, all of whose names are known to posterity, made good or even brilliant marriages in terms of wealth and status, and their husbands were important figures or major vassal rulers linked politically to Chinggis Khan.Footnote 123 Furthermore, Chinggisid princesses who married vassal lords and produced sons could expect to see their sons succeed to the vassal’s throne.Footnote 124 Striking examples of the impact of Chinggisid princesses on succession appeared in Korea, first in 1298, when a ruler was deposed for refusing to have sex with his Mongol princess wife, and again in the thirteen-teens, when a Korean king requested three Chinggisid wives in succession, despite the fact that he had sons from other women.Footnote 125

In contrast to the benefits heaped on the children of senior wives, the offspring of junior wives could expect lesser favors, as could the children of concubines. Chinggis Khan’s junior children had respectable careers, but they were less brilliant than those of their senior half-siblings, despite claims to the contrary.Footnote 126 Daughters of junior wives made good marriages but not brilliant ones, while junior sons enjoyed military careers, but could not even dream of ruling.

Women and Politics

Women and men both played active roles in steppe politics. High-ranking women in particular joined men in the public expression of political power by attending and participating in political ceremonies, while decrees could be issued jointly through the authority of a man and his wife or wives.Footnote 127 Many women made strategic marriages and thereby participated in networks of personal and political connection, as will be discussed shortly. Women with access to political information could use it to advise others or shape policy. Finally, and as mentioned previously, women managed the essential activities of everyday life, which allowed men to engage in their specialties of raiding and war.

Women in the Mongol Empire and the successor khanates participated most visibly in politics at formal ceremonies like quriltais, coronations, and receptions of ambassadors. Visitors particularly noted the presence of women at official gatherings. As elsewhere in Mongol life, physical space was assigned to each gender: men sat to the right of the ruler, women to the left. Usually all of an important man’s wives attended these ceremonies, but only the senior wife sat next to her husband, often on a raised dais, while the others sat below on designated benches or other seats.Footnote 128 (See Figure 1.3.) Thus for example the senior wife of the Jochid prince Sartaq received Friar William with her husband, and together they examined an incense burner and psalter that Friar William showed them.Footnote 129 Other women present at political events could be the daughters, sisters, aunts, and mothers of important men.Footnote 130 Ambassadors also routinely met with women independently from their meeting with the ruler, and might be given food, drink, and gifts by the wife or her servants.Footnote 131 In later centuries, nomadic wives usually received diplomats a few days before their menfolk. It has been suggested that the women were vetting the visitors in order to help men prepare for a later audience.Footnote 132 Unfortunately the existing information is too scant to tell us whether there was a Mongol precedent to this behavior.

Women also attended informal political meetings: if a man discussed politics inside any ger other than his own ceremonial pavilion, the ger always belonged to a wife, who would be there waiting on (or directing servants to wait on) her husband and his guest as well as participating in or listening to their conversation. In this way women’s roles in hospitality could involve them in politics. One such highly informal interaction took place between Temüjin and his youngest brother Temüge when the latter burst in late at night after a set-to with the shaman Kököchü. Since Temüjin was in Börte’s ger, she participated in the conversation.Footnote 133

Some women were therefore well-positioned to gain valuable knowledge of politics, personalities, and current events, which they could then use to advantage. But women rarely seem to have employed their political acumen openly for themselves; rather, historical and literary evidence suggests that they shared their ideas with men, many of whom deliberately sought out and followed women’s advice.Footnote 134 Thus on one occasion Temüjin asked both his mother and wife about a cryptic comment that his friend Jamuqa had made, and decamped with all his followers as a result of Börte’s political advice.Footnote 135 Similarly both Hö’elün and Börte provided important political analyses and advice when Temüjin faced rivals, while the Tatar wife Yisüi is credited with convincing Temüjin to settle the question of succession to his throne.Footnote 136

In addition to acting as advisors to their immediate contacts, women could interact extensively with a wide range of political players. A description of the Chinggisid princess Kelmish Aqa illuminates the networking practices of a politically active Chinggisid woman:

Toqta [of the Jochids, (r. 1291–1312)] and the other princes hold her in a position of great importance. Since she is the offspring of [Chinggis Khan’s son] Tolui Khan, she shows a constant affection to the Padishah of Islam [Ghazan in Iran (r. 1295–1304)] and continually sends emissaries to inform him of events that transpire in that realm. It is due to her that friendship has been maintained and strife and enmity avoided between Toqta and Jochi’s Khan’s other offspring and Tolui Khan’s house. When [Qubilai’s son] Nomoghan was surprised and seized by his cousins and sent to Möngke-Temür, the ruler of Jochi Khan’s ulus [land and peoples], Kelmish Aga exerted herself to have him sent back to his father with honor in the company of some of the princes and great amirs [commanders].Footnote 137

Nevertheless, few women ruled openly, and then only under certain circumstances. As noted above, more often women shared rule with their husbands by participating in government and enjoying inclusion on official decrees, most clearly among the fourteenth-century Golden Horde, Chaghatayids, and Ilkhanids.Footnote 138 Or, when a lesser Chinggisid or other important Mongol man died, his widow could administer his personal territory and continued to receive his revenues, income, gifts, and other resources.Footnote 139 A third possibility was for a woman to rule as a regent on behalf of a son for a limited period of time. This was the case for Börte’s third daughter, Alaqa, who governed Öng’üt territory for a son; for Töregene, who ran the entire empire after Ögedei’s death until enthroning her own son Güyük; and for Chinggis Khan’s granddaughter, Orqīna, who ruled the Chaghatayid Khanate for a decade, also on behalf of a young son.Footnote 140

Women also contributed to steppe politics by marrying the allies of their menfolk. Typically men formed certain kinds of alliances and friendships with other men. When enough such relationships were established among individuals, families, or lineages, larger organizations could result, among them confederations, as outlined above. But although scholars have focused on the political links among men, it is vital to remember that in most confederations these male alliances were matched by marriage ties between the two sides, which equally helped hold confederations together.Footnote 141

This was the realm of in-laws. Among the Mongols, the word quda referred to in-laws in a general sense: when negotiating the marriage between Temüjin and his senior wife Börte, for example, the fathers in question, Yisügei and Dei Sechen, referred to one another as quda.Footnote 142 (A son-in-law earned a special name: küregen.)Footnote 143 The relationship of quda was one of mutual affection and assistance between the marital partners, and between their families. In this way it differed from other forms of political alliances between men, which only linked individuals.Footnote 144 Marriage negotiations were conducted with the assumption that both sides would benefit from the match, especially if the families involved had political standing.Footnote 145 Some benefits were long-term, as when a woman married a man expected to hold political power in the future. This was the case when the previously mentioned leader Dei Sechen engaged his daughter Börte to the young Temüjin, who could be expected to take over his father Yisügei’s position as war leader.Footnote 146 Other benefits were more immediate, such as when the Kereit leader Jaqa Gambu married his loveliest daughter to the Tangut ruler Weiming Renxiao (r. 1140–93, Renzong) in return for immediate status in Tangut lands, or when Jaqa Gambu’s brother Ong Qan matched his own daughter, Huja’ir, with the Merkit leader Toqto’a in return for protection in exile.Footnote 147 At other times marriage obligations could be perilous – the Mongol-Tatar feud that shaped Temüjin’s early life began as a disagreement between the Qonggirats and the Tatars, not the Mongols, but expanded to include the Mongols because of their in-law connections with the Qonggirats.Footnote 148

Particularly among political families, strategic marriages created a network of female and male informants across a confederation, whose loyalties were multiple and complex, and who were well-positioned to gather political information and send it where it could be useful.Footnote 149 Women could therefore draw on their birth families, their children, and sons- or daughters-in-law, and even their co-wives for information. Thus, for example, Temüjin’s divorced Kereit wife Ibaqa traveled to Mongolia from China each year to consult with her sister Sorqoqtani, host parties for the major political players in the realm, and confirm her political and social connections at the heart of the empire.Footnote 150 Women with rank, privilege, and wealth also controlled additional networks of servants, staff and retainers. The daughters of such women must have learned both political savvy and the best ways to express political advice from their mothers, grandmothers (and perhaps stepmothers), then later applied them as situations warranted.

A nomadic lord could use the in-law relationship and the networks it created to promote and maintain his own power. One simple way to do this was to make a political subordinate into a son-in-law, which honored him, elevated him politically, and also guaranteed his service. Chinggis Khan did this with his Turkic sons-in-law from Qara-Khitai territory in 1211.Footnote 151 Less benevolently, a strong nomadic ruling family might seek to control the people ruled by the lineage into which it had married. This was the secret fear of Ong Khan of the Kereits when Temüjin proposed a double marriage between their families: the Kereits had endured unwanted in-law meddling before, and so Ong Khan saw the matches as a prelude to a takeover and refused to cooperate. Temüjin soon proved these fears to be well-grounded when he conquered the Kereit people and subjugated its rulers, albeit without the sanction of the in-law connection that he himself had suggested.Footnote 152

Later, Chinggis Khan used the ties of obligation and affection enshrined in the in-law relationship to bring other nomadic or semi-nomadic peoples, like the Öng’üts, Oirats, Uighurs, and Qarluqs under his control without actually having to conquer them; unlike in the case of the Kereits, however, he left their subject people and their realms intact.Footnote 153 These “conquests” took place through the marriages of Chinggis Khan’s daughters and granddaughters to these rulers, which made the brides into general managers of people, property, and resources for their princely husbands, according to steppe custom. These women were thus perfectly positioned to act both as local informants for Chinggis Khan, and as political advisors for their husbands, while their husbands gained political rights and privileges among the Chinggisids.Footnote 154 This reliance on the political network formed by in-law or consort families became business-as-usual throughout Mongol territory; indeed, after the Mongols were driven out of China in 1368, their Ming successors implemented a policy of restricting the activities, power, and influence of in-law families, which may have been a response to Chinggisid customs.Footnote 155

Women’s Loyalties

Whereas steppe women’s marriages, work, and childrearing have commanded some scholarly attention, no attention has yet been paid to the larger question of women’s mental energy, especially their loyalty, its focus, and the way it affected their behavior. The historical sources and literature mention loyalty in passing, usually when praising a woman for demonstrating it in a socially acceptable way. Thus the mother who worked herself to the bone for her children, the senior wife who remained sexually faithful to her husband, or the junior wife who advised her husband wisely were directly or indirectly lauded as exemplars of women’s loyalty and its proper expression.Footnote 156 But the realities of women’s experiences, and the ways they actually behaved, suggest that their real loyalties were far more complex than has been previously assumed.

It is helpful first to consider women whose loyalties were straightforward, that is, women who grew up in one family, married into another, and bore children, all without encountering abduction, captivity, rape, violence, or other hardship along the way. Scholarship on nomadic marriage has suggested that the bride price system limited married women’s contact with their birth families, since once the bride price was paid the woman was no longer her family’s responsibility; the levirate only exacerbated this situation, since a widow was a concern for her in-laws alone.Footnote 157 The resulting conclusion is that a married woman’s loyalty was directed solely at her immediate family – her husband and children. Or was it? In contrast to scholarly claims, the historical sources suggest that daughters of steppe leaders maintained a sense of responsibilities that extended beyond their own wifely households to the peoples their parents ruled; that is, they retained their loyalty to their birth families and subjects even after marriage, and even as they developed new loyalties to their husbands and children. A famous poetic passage from the Secret History suggests that a well-placed steppe wife was entrusted not just with managing her husband’s wealth and their family, but with protecting her own parents, kin, and people. The passage describes Qonggirat women, who were famed for their beauty:

These lines imply that a woman who married a leader was expected to keep her family and people in mind even after she rode off to a new life, regardless of the mechanics of bride price or levirate.Footnote 159 Accordingly, then, even if a woman had only limited contact with her birth family after her marriage, out of sight was not supposed to mean out of mind.

Additional Chinggisid examples suggest that women in advantageous positions might continue to interact with their families after marriage, sometimes extensively. Although the tremendous political power Chinggis Khan wielded after 1206 certainly facilitated the abilities of his wives or mother to contact their families, it was not the only factor at play, since concepts of loyalty to birth family joined Mongol preferences for exchange marriages with a wife’s relatives. One example was Temüjin’s mother Hö’elün, whose relatives were not even on terms with her kidnapper husband Yisügei. Nevertheless, Yisügei deliberately chose Hö’elün’s Olqunu’ut family as the one in which to find a wife for their son Temüjin, and the patterns of exchange marriage suggest that the bride would have been one of Hö’elün’s close relatives.Footnote 160 Although ultimately Temüjin’s bride (Börte) came from the Qonggirats instead of the Olqunu’uts, Yisügei’s original intent might have enabled Hö’elün to reestablish contact with her family. Later after Yisügei’s death, Hö’elün’s youngest son, Temüge, did marry an Olqunu’ut woman, which Hö’elün probably helped arrange.Footnote 161 Thereafter Chinggis Khan’s unique position further supported Hö’elün’s renewed contact with her people, since he gave her the Olqunu’ut subjects to command in 1206; at the same time her male relatives became commanders of a thousand in Chinggis Khan’s army and married among Chinggis Khan’s junior daughters.Footnote 162

Börte also interacted with her family after marriage, although the Qonggirats profited far more from Börte’s position than the Olqunu’uts did from that of Hö’elün. Although we know nothing about Börte’s early contact with her people, the Qonggirat submission to Temüjin in 1203 certainly facilitated her (re-) connection to her relatives. Thereafter Chinggis Khan made some of Börte’s male kin into commanders of a thousand in his army.Footnote 163 He and Börte also married one daughter to a Qonggirat man (a nephew or adopted nephew), and two sons to Qonggirat women.Footnote 164 It is reasonable to assume that both families were involved in the negotiations, and that both attended the weddings and the installment of the brides with their new husbands. Later the Qonggirats became the most important consort lineage for the Chinggisids, which further facilitated exchange between the families.Footnote 165

Additional examples of contact between steppe wives and their birth families include those of Chinggis Khan’s daughters who left Mongolia once they married.Footnote 166 Some of these women may well have encountered their father again during his conquests, since the Mongol armies crossed their territories, and their husbands joined Chinggis Khan’s forces with their own warriors.Footnote 167 The princesses who married among Chinggis Khan’s own followers were even more likely to see their natal family, since their husbands continued to work for their father.Footnote 168 Furthermore, even when a Chinggisid woman held the uneasy role of representing the Golden Lineage in a vassal country, as in Korea beginning in the 1260s, princesses were able to go back home for visits (in the Korean case, to Yuan China).Footnote 169

But it is even more likely that women maintained multiple loyalties in cases where their lives were interrupted by hardship, despite the fact that these loyalties are harder to prove. Particularly in the violent and chaotic period before the rise of Chinggis Khan, steppe women were especially vulnerable to capture, rape, or other trauma. For a captured wife or daughter, then, where was her loyalty to go? In theory, to her new husband, even if he had just had her family and people killed. In reality, who can say? We cannot know the thoughts of people from such a different world, and the historical sources breathe no word of conflicts raging within these women’s minds. But they were still humans as we are, and we can at least imagine that some captives may have harbored anger, resentment, or hatred. Many of Chinggis Khan’s own women in the early years were daughters of conquered peoples, among them his wives Qulan, Ibaqa, Yisüi, and Yisügen, as well as the Jin and Tangut princesses, while conquered women who married his sons and grandsons included Töregene, Oghul Qaimish, and Sorqoqtani.Footnote 170 Unfortunately the historical sources, and the scholars, have generally not thought even to question where these women’s hearts lay, or have assumed that their husbands or their children became their all.Footnote 171

A clear example of women’s contested loyalties does appear in the case of Chinggis Khan’s Tatar wives, Yisüi and Yisügen, who went to Temüjin as part of the spoils when he annihilated the Alchi Tatars in 1202. As daughters of a leader, the sisters became Chinggis Khan’s wives, not concubines; they then used their position to help those Tatars left alive. They contrived to rescue a few survivors almost immediately, then later maneuvered to gather the others in a remarkable, albeit extremely partial, reconstitution of their destroyed people.Footnote 172 The sisters thus maintained a sense of responsibility to their former subjects, alongside their new responsibilities in the households they were forced to establish with Chinggis Khan.

It is therefore essential to consider the question of women’s mental energy, and particularly their loyalty, in order to understand their lives in nomadic society. The wide varieties in women’s experiences, and the specifics of their behavior, suggest that their loyalties were multiple, complex, and sometimes hidden. Although the scholarly assertion that women were cut off from their families after marriage may be useful as a general rule, it must be tempered by the reality of measurable contact between a woman and her people, as shown in many Chinggisid examples.

Conclusion

Before we turn to specific women in the Mongol empire, it has been vital to investigate the general realities of steppe women’s lives. This investigation has focused on married women, since it was particularly after marriage and childbirth that women were best positioned to exercise their powers. They then spent their lives engaged in a tremendous variety of activities: caring for animals, raising children, supervising workers of many kinds, and carefully husbanding or exploiting the human, animal, or other resources they controlled. Women were an economic mainstay for the families into which they married, and bore heavy responsibilities. Without their logistical, managerial, and economic contributions, to say nothing of their daily labor, steppe life could not have functioned: men would not have been free to raid, or to fight, or even hunt, and the histories of the great steppe empires would be very, very short. In what follows we will examine the individual women important in the life of the greatest empire-builder of them all, Chinggis Khan, and will consider their unique contributions to Mongol history in the specific light of their womanly training, abilities, world-view, and circumstances.