Every Saturday morning several hundred street vendors in an informal market in the center of Medellin, Colombia, pay a “tax” to members of a violent criminal organization. The vendors are recicladores (recyclers) that scour trash bins for items to repair and sell. In exchange for their payment as part of this criminal protection racket, vendors receive the promise of security from everyday crime and the criminal organization itself.Footnote 1 Those unable or unwilling to pay incur violent punishments that can range from a slap on the back of the head to immobilization by Taser before being urinated on. But as evident from the story of one vendor, Don Alfonso,Footnote 2 denouncing the racket itself risks more serious punishment.

Don Alfonso sold old tools in the market. One day he began to publicly complain about the security tax. Another vendor lamented: “We told him it was better to be quiet. But he didn’t listen. He was old and tired of this shit. Soon the media arrived. That was the beginning of the end.”Footnote 3 Weeks after stories about the protection racket appeared in local papers, Don Alfonso was shot in the head in the middle of the market. The killer was never apprehended. The next Saturday the racket’s collectors were back collecting the tax. As one vendor noted: “It’s like the sun rising. You can always count on them showing up and opening their hands to get paid.”Footnote 4

This story aligns with part of the conventional wisdom in research on the politics of crime that views victims as resigned to their fates at the hands of coercive criminal actors. Crime trends in the developing world are certainly concerning. In 2013 Africa and Latin America had the world’s highest homicide rates of 12.5 and 16.3 per 100,000 people, respectively, compared to the global average of 6.2 per 100,000 (UNODC 2014, 22). Between 2003 and 2008 the average percentage of Latin Americans that perceived their country to be less safe increased from 18% to 59% (Casas-Zamora Reference Casas-Zamora2013, 31), and today over one-third of the region’s population views crime and insecurity as the most pressing problems in their countries (CAF 2014, 211). In Sub-Saharan Africa, nearly one-third of urban residents feel “very unsafe” walking on the streets after dark (Baliki Reference Baliki2013, 3). And criminal violence afflicts populations in U.S. and Western European cities as well (Vargas Reference Vargas2016; Wacquant Reference Wacquant2008). Scholars and policymakers agree on the need to better understand “the relationship between politics and violence in the contemporary world” (Barnes Reference Barnes2017, 980).

One area in need of greater understanding is the political interaction between victims and criminal victimizers. Some studies argue that victimization leads people to withdraw from political life into a “low intensity citizenship” (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993) where their political and social rights are systematically violated. Others find that victimization spurs political engagement, from civic organizing to engaging in political discussions. Both lines of research offer valuable, though somewhat contradictory, insights into the political consequences of crime. But both also overlook whether and how victims engage their criminal perpetrators. I began to consider this point halfway through the first of several focus groups that I conducted with informal vendors in Medellin. The six vendors in the room were visibly tired of my questions about how often and how much they paid under the protection racket—my attempt to understand what I assumed was the extent of their victimization. One vendor, an approximately fifty-year old man who sold used cell phone chargers, finally (and thankfully) motioned for me to stop. He explained:

It’s not only that I have to pay every Saturday. That hurts me … all of us, of course it does. But that’s only one part of the problem: something bigger with the Convivir (term used for the groups that coordinate protection rackets in Medellin’s downtown). When [the racket’s collectors] take the money from me, I don’t stop being a victim. He doesn’t stop being a victim (pointing at a vendor sitting across from him). She doesn’t stop being a victim (pointing at a vendor sitting beside him). Like them, I am a victim 12 hours a day and seven days a week (the average work schedule for a vendor)—every single time I step foot in the market, I am a victim.Footnote 5

The prevailing approach to criminal victimization as a traumatic but one-time act is insufficient to understand its ongoing nature. It limits our ability to observe, conceptualize, and theorize how victims exercise agency vis-à-vis their criminal perpetrators. It also conceals the behaviors and practices that criminal victimizers undertake to carry out and sustain victimization, but which are overlooked by the traditional focus on their use and threat of coercive force. Analyzing victimization as a dynamic and interactive process offers a fuller understanding of the politics of criminal victimization.

In this article I first show that whereas emerging research provides important insights into the political consequences of crime, it neglects the inherently political nature of victim-criminal actor relations. The second section conceptually distinguishes between crime as an act and victimization as a relational process to reveal a layer of contentious politics between victims and criminals. I then develop a theoretical framework to analyze these dynamics by drawing from research on power, domination, and subordination. I illustrate the framework’s analytic utility in the third section of the paper with an empirical analysis of the victimization of informal vendors under a criminal protection racket in Medellin. Diverse criminal organizations, from youth gangs to drug trafficking organizations, coordinate similar rackets across Latin America (Oxford Analytica 2016), Africa (Shaw Reference Shaw2016), and Eastern Europe (Frye Reference Frye2002; Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993; Varese Reference Varese2001; Volkov Reference Volkov2002). For the empirical analysis I use data from focus groups, interviews, and participatory drawing exercises. I finish by discussing the implications of my analysis for future research on crime and policy efforts to stem it.

The Politics of Crime: Emerging Insights and a Persistent Gap

Crime challenges order and development (Arias Reference Arias2017; Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Durán-Martínez Reference Durán-Martínez2018; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2015; Lessing Reference Lessing2018; Moncada Reference Moncada2016; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2018; Ungar Reference Ungar2002; Yashar Reference Yashar2018). One strand of the emerging research on crime sees victims as resigned to the harm inflicted upon them by criminal actors amid absent or complicit states in contexts of “endemic fear and insecurity” (Moser and McIlwaine Reference Moser and McIlwaine2004, 3-4). Criminal violence depresses electoral participation by increasing the risks associated with voting and eroding trust in the political system (Ley Reference Ley2018; Trelles and Carreras Reference Trelles and Carreras2012). This echoes the finding of a negative relationship between levels of crime and the perceived legitimacy of political institutions, as well as support for democracy (Carreras Reference Carreras2013; Malone Reference Malone2010; Pérez Reference Pérez2003; Visconti Reference Visconti2019). By contrast, others argue that victimization can spur non-traditional forms of political engagement, including attending community meetings and assuming leadership roles in civil society (Bateson Reference Bateson2012; Dorff 2017). This corresponds with the finding that victims of wartime violence are more likely to become politically engaged relative to non-victims in post-conflict settings (Bellows and Miguel Reference Bellows and Miguel2009; Blattman Reference Blattman2009; Voors et al. Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and Van Soest2012). The focus on victims either engaging or withdrawing from the state, however, overlooks the political nature of relations between victims and criminals. Certainly anthropological studies argue that contemporary lynchings of criminals are political performances, or “moral complaint[s]” (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003, 22-43)Footnote 6 meant to chastise states for disregarding marginalized populations in contexts of resource scarcity. But this still reduces the victim-criminal actor relationship to one of physical violence and locates politics only in the (violent) “dialogue” between victims and the state.Footnote 7

The interactions between victims and criminals may initially seem beyond the scope of a conventional view of politics as phenomenon within the public realm. But victim-criminal actor relations are inherently political. Politics understood as competing efforts to shape the distribution of resources among actors, or “who gets what, when, how” (Laswell Reference Lasswell1936, 3), is not limited to the formal public realm.Footnote 8 As Robert Dahl (1963, 72) said: “Let one person frustrate another in the pursuit of his goal, and you already have the germ of a political system.” Carol Pateman and feminist scholars have convincingly shown that the “personal is political” through studies on gender, sexuality, and citizenship (Nicholson Reference Nicholson1981)Footnote 9 as well as on regimes, states and markets (Pateman Reference Pateman1988). More broadly, though much political science research focuses on the state as the protagonist of political life—what David Easton (1953, 129-34) identifies as the source of the “authoritative allocation of values”—it is not always the only, or even the primary, authority in shaping everyday lives. Instead the state is often one among several actors that orders populations, territories and lives, such as powerful firms in company towns (Gaventa Reference Gaventa1982), large landowners (Scott Reference Scott1985), rebel groups (Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Mampilly Reference Mampilly2012), and urban gangs (Moncada Reference Moncada2013). Sustained interactions to contest the distribution of resources between civilian and non-state actors, including criminal actors, can therefore be fruitfully analyzed as political in nature.Footnote 10

The Politics of Criminal Victimization: A Theoretical Framework

Until the mid-twentieth century, the field of criminology was surprisingly a “victim-free zone” (Dignan Reference Dignan2004, 16) that focused on explaining why people committed criminal offenses. But a sub-field known as “victimology” urged criminologists to conceptualize victimization as a “duet” between the victim and the perpetrator in order to analyze the “problem of dynamics” inherent to victimization (Von Hentig Reference Von Hentig1948), but which were eclipsed by the predominant view of crime as an act. Yet analysis of the interactions between victims and perpetrators ultimately centered on whether the attributes of a victim—the clothing they wore or the streets they frequented—made them more or less vulnerable to particular criminal acts. The broader relational aspects of the victim-criminal actor dyad were overshadowed by an approach ultimately critiqued for its preoccupation with establishing the degree to which the victim was to blame for their own victimization (Mukherjee Reference Mukherjee and Schneider1983, 121). It is here where we can harness insights from political science’s longstanding study of power, domination, and subordination to advance our understanding of the politics of criminal victimization.Footnote 11

A crime is an act that violates a formal law codified by the state.Footnote 12 I define criminal victimization as the extent of the direct interaction between victims and the perpetrators of the crime. Victimization is thus a process that encompasses the criminal act, but crucially, can extend beyond it to include other interactions between victims and criminal actors. These interactions can vary in length and nature, but they all entail the negotiation of material and non-material resources between the two parties. Figure 1 provides a simple visual representation of this conceptual decoupling.Footnote 13

Figure 1 Conceptual decoupling: Crime as an act, victimization as a process

Note: C = criminal act and V = process of victimization.

The duration of a criminal act and the span of direct interaction between a victim and their victimizer can overlap substantially, as in the case of a house break-in. Here a focus on explaining the distribution of the criminal act across space and time would be analytically fruitful. But as shown in figure 1, the degree of overlap between the criminal act and the process of victimization varies across distinct types of crime. In particular, we need to distinguish between crimes that are one-time acts versus those that are ongoing.

A kidnapping is the act of taking or detaining someone by force, often for a ransom. But the associated process of victimization features other interactions where power between victim and victimizer is contested and negotiated. Stockholm Syndrome is a bond of dependence and even affection that victims develop for their kidnappers over time, but which victims may strategically cultivate in order to obtain improved treatment (Ochberg Reference Ochberg1978). Kidnappers engage in calculated practices beyond physically detaining their victims, including sensory deprivation, name-calling, and humiliation, but also “positive experiences for victims” in the form of “the provision of newspaper and radios … food, books, and television” and “clean clothes” (Phillips Reference Phillips2011, 846-47; 865). Unpacking criminal victimization can provide surprising insights into what aspects of the process most impact victims, as illustrated by the following testimony from a kidnapping victim:

When I wanted to go to the bathroom, I had to wait until they brought me a bucket. Sometimes they would leave the bucket in the room to harass me. The sense of humiliation I felt at not being able to decide when to use the bathroom was tremendous. Even worse was trying to do my private business while blindfolded, with someone standing over me, and having to beg them for toilet paper. This was absolutely the worst aspect of the whole experience for me” (Wright Reference Wright2009, 49, emphasis added).

Though physical detention defines the criminal offense, the associated process of victimization includes other interactions that shape the overall relationship between victims and victimizers.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is another instructive example. One out of every three women in the United States has experienced “sexual assault, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner” (Triantafyllou, Wang, and North Reference Triantafyllou, Wang and North2016, 2) during their lifetime. But the individual criminal act of IPV cannot be fully understood without assessing the broader interactions constitutive of the victim-perpetrator relationship. A multi-country survey by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that female victims of IPV regularly experience concurrent emotional abuse at the hands of their abusive partners, including “being insulted or made to feel bad about oneself; being humiliated in front of others; being intimidated or scared on purpose” (WHO 2005, xiii). Though a majority of victims characterize the emotional abuse as more damaging than their physical injuries, we still know little about the former precisely because of the conventional focus on the physical violation (Ibid., 35).Footnote 14 Decoupling crime and victimization therefore makes visible intriguing dynamics of the process of victimization. To analyze these dynamics I theorize relations between criminals and victims as analogous to those between dominant and subordinate actors.Footnote 15

Domination, Subordination, and Resistance as Political Dynamics of Criminal Victimization

Whether criminal rulers, elected politicians, or self-appointed dictators, dominant actors use a range of practices to subordinate populations, as shown in table 1.

Table 1 Strategies and practices of domination

Material domination is the use or threat of coercive force to extract material rents from subordinates. Coercive force is necessary, but not sufficient, to tax populations. As Margaret Levi notes, “without a fairly high degree of quasi-voluntary compliance, revenue production policies are not even feasible” (Levi Reference Levi1989, 13). To obtain this compliance actors combine material with social and political strategies of domination.

Social domination seeks to undercut efforts by subordinates to raise issues that can threaten the power of dominant actors. Bachrach and Baratz (Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962) called this the “second face of power.”Footnote 16 A classic example is political actors using the status quo biases embedded within policymaking institutions to set agendas in ways that constrict debate (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Hall and Wayman Reference Hall and Wayman1990). Dominant actors in contexts of criminal victimization can similarly invoke predominant social norms to affirm the social hierarchy between themselves and their victims. These “symbolic taxes” (Scott Reference Scott1990, 188) include using “humiliation, disprivilege, insults, [and] assaults on dignity” to elicit “deference, demeanor, posture, verbal formulas and acts of humility” (Ibid, 198). Such practices can prevent challenges to the status quo distribution of power. As a researcher of domestic abuse notes: “Victimization works best when the perpetrator produces a sense of immobilization and helplessness and a loss of self-respect” (Boss Reference Boss2002, 161). We thus need to analyze social control as an important dimension of criminal victimization.Footnote 17

Dominant actors also sustain victimization through a “third face of power” that prompts victims to question the legitimacy of their grievances and so “accept their role in the existing order of things” (Lukes Reference Lukes1974, 11). Lisa Wedeen (Reference Wedeen1999) argues that authoritarian rulers saturate society with conservative political rhetoric and symbols to shape the acceptable boundaries of state-society relations. John Gaventa (Reference Gaventa1982) identifies how economic elites structure political norms to dissuade the poor from seeing their concerns as legitimate. Parallels can be drawn with aspects of criminal victimization. Psychological studies of sexual violence examine “rape myths,” defined as “attitudes and beliefs that are generally false but are widely and persistently held, and that serve to deny and justify male sexual aggression against women” (Lonsway and Fitzgerald Reference Lonsway and Fitzgerald.1994).Footnote 18 An example is the notion that women invite sexual violence by dressing or acting in “suggestive” ways. Such myths deny victims of sexual violence their rights and legitimize continued victimization (Burt Reference Burt1980). Thus whereas my focus is on the interactions between victims and criminals, these are not detached from how both states and society view victims based on their socioeconomic, racial, or gender identities.Footnote 19 Greater attention to when and why criminal actors invoke broader social norms to shape their victims’ understandings of their political subjectivity can deepen our understanding of victimization.

Analyzing victimization as a process also challenges us to consider how victims exercise agency vis-à-vis criminal actors. Building on James Scott (Reference Scott1985, Reference Scott1989; Reference Scott1990), I operationalize agency as publicly observable acts of resistance by victims to negotiate the terms of their victimization directly with their criminal victimizers. Researchers have drawn on Scott’s work to study “everyday” resistance in diverse contexts, including by black laborers against white business owners during the Jim Crow era (Kelley Reference Kelley1993), civilians against rebel groups (Arjona Reference Arjona2016), and ordinary citizens against authoritarian regimes (O’Brien Reference O’Brien1996). We should expect that victims of crime too will negotiate the material, social, and political dimensions of subordination. It bears emphasis that contestation along everyday lines will not end victimization (Rubin Reference Rubin1996).Footnote 20 But everyday resistance can help victims to obtain what they understand to be practical, emotional, and political dividends amid victimization.

Two factors define the scope conditions for this theoretical framework. First, because it emphasizes the interactions between victims and criminal actors, the framework is applicable to cases where victimization is ongoing and not a one-time act. The framework helps to analytically parse the criminal act from the process of victimization and assess the links between the two. The framework can also be applied to cases where criminal organizations govern aspects of everyday life while simultaneously committing criminal offenses against the populations in the territories under their control.Footnote 21 Second, the theoretical framework is most useful for analyzing cases where the state is unable or unwilling to advance the rule of law. Because victims in such settings may face greater incentives to contest their victimization directly vis-à-vis their victimizers, the framework can help to make sense of the multi-dimensional nature of the interactions between the two. Contexts where these conditions are likely to be found include violent “urban peripheries” in both the Global South (Arias Reference Arias2017; Denyer-Willis Reference Denyer-Willis2015, 7-8; Holston Reference Holston2008; Moncada Reference Moncada2013) and North (Wacquant Reference Wacquant2008), as well as settings marked by the uneven state provision of formal rights along demographic lines. The latter includes gender-based violence in patriarchal contexts (Heise Reference Heise1998), criminal victimization within minority racial and ethnic enclaves (Alves Reference Alves2018),Footnote 22 and settings where the criminal justice system systematically discriminates against particular social classes or racial groups (Van Cleve 2016).

Criminal Victimization under a Protection Racket: Empirical Analysis

Before proceeding with the empirical analysis I define criminal protection rackets, discuss their manifestation in Colombia and Medellin, and outline the strengths and limitations of the research design and methods.

Conceptualizing Rackets

Criminal protection rackets are ongoing arrangements under which one actor pays tribute to a coercive actor in exchange for the promise of protection from external threats and the coercive actor itself. How is this different from extortion? Varese (2014, 350) defines extortion as taxation for “services that are promised but not provided,” whereas rackets are ongoing arrangements where payment of tribute offers security from some dangers (Volkov Reference Volkov2002, 35). Studies of European criminal rackets indicate that they provide seemingly effective protection to business firms from everyday crime and the violation of contracts (Frye Reference Frye2002; Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993; Volkov Reference Volkov2002; Varese Reference Varese2001). This may reflect the fact that rackets in these settings emerged in response to demand for protection amid the shift from statist to market economies (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993, 17).Footnote 23 But this does not rule out potential variation in the quality and efficacy of the type of protection that rackets can provide.Footnote 24 In Latin America, including in the case that I analyze here, the protection that rackets provide varies in quality and efficacy, though their criminal coordinators still use the promise and occasional provision of protection to justify the “security tax.” As I discuss in the conclusion, this variability provides an opportunity for comparative research on criminal protection rackets.

Criminal Protection Rackets in Colombia

Criminal protection rackets in downtown Medellin, which is called the Comuna 10,Footnote 25 are run by groups called Convivir, a term that paradoxically translates as “living in harmony.” In 1994 the Colombian national government authorized the creation of the Convivir as civilian self-defense groups trained and armed by the military to combat insurgent forces in the country’s decades-old civil war.Footnote 26 Politicians and economic leaders, however, established Convivir to safeguard their particular interests given the state’s limited territorial reach.Footnote 27 The Convivir found an ardent advocate in Álvaro Uribe Vélez, then governor (1995–1997) of the department of Antioquia—of which Medellin is the capital—and subsequently president (2002–2010) and then a senator (2014–) long alleged to have links with right-wing paramilitary groups. Uribe encouraged the establishment of Convivir in nearly all of Antioquia’s municipalities (El Tiempo 1996; Razón Publica 2011), many led by paramilitaries that used them to target civil society leaders and political leftists (Semana 1996). In 1997 the Colombian Constitutional Court limited the activities that the Convivir could undertake, their use of weapons, and the ability of their members to remain legally anonymous. But the Convivir in Antioquia, and particularly in Medellin, had by then begun forcibly collecting security taxes from businesses and residents in the territories where they operated in order to sustain themselves. The protection services were initially welcomed given the context of intense drug-related violence (Moncada Reference Moncada2016, chap. 3). But as violence declined over time, so too did the quality and level of protection, despite the collection of security taxes remaining constant.

Today the Convivir in the Comuna 10 are run by street gangs that work for larger criminal organizations based in the city’s peripheral neighborhoods, known as bandas or oficinas (offices), that coordinate the sale of illicit drugs, weapons, and assassinations for hire. City officials estimate that approximately twenty Convivir operate in the Comuna 10, though local civil society leaders place the figure closer to forty, with anywhere between 750 to 1,200 members (Bargent Reference Bargent2015). The concentration of businesses in the city center makes it a prime target for establishing criminal rackets that generate an estimated one-third of a million dollars every month (El Tiempo 2014).

Case Selection

Between 2016 and 2017 I carried out nearly five months of fieldwork in one informal market in the Comuna 10. The market stretches several city blocks and has about 400 informal vendors that work seven days a week, twelve hours a day. It emerged in 2011 when the vendors were displaced from their previous locale by local authorities that alleged criminals were using the site to sell drugs.Footnote 28 Shortly after the vendors relocated, a local gang that was part of a larger criminal organization known as the Office of the Valle de Aburrá informed the vendors that the market was now under their protection as a Convivir.Footnote 29 Each vendor is expected to pay a weekly “security tax” of two thousand Colombian pesos.Footnote 30 As vendors note: “O paga o paga” [either you pay or you pay], meaning that if the racket’s enforcers cannot collect the tax from a vendor, they violently tax the vendor’s body.

There are several reasons why this analysis should have implications relevant beyond my field-site. The unit of analysis is the dyadic relationship between the vendors and the criminal gang within the market. I zoom down to the micro-level space most relevant for analyzing the choices and behaviors of the key actors in my theoretical framework—what Arjona (Reference Arjona, Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019) calls the “locus of choice.” This strategy isolates theoretically-relevant characteristics to identify analytically comparable units of analysis across distinct empirical settings—what Przeworski and Teune (1970, chap. 5 and 6) termed “cross-system equivalence.” A limitation of the research design is that the politically contested nature of the urban informal economy may limit the type of resistance that the informal vendors can pursue relative to victims located in the formal economy.Footnote 31 Yet this is precisely why informal vendors represent a “least-likely case” (Gerring Reference Gerring2007, 232) for resisting criminal victimization, making the evidence that they do so all the more theoretically intriguing.

Methods

Observing, documenting and analyzing the meaning of interactions between victims and criminals required ethnographic fieldwork and multiple methodologies.Footnote 32 I conducted focus groups with informal vendors. Focus groups can help to establish a temporary space where marginalized populations may be more at ease discussing sensitive topics given their social nature relative to one-on-one interviews (Laimputtong Reference Laimputtong2011, 9). In addition to individual-level data, Cyr (Reference Cyr2016) identifies two other forms of data that focus groups generate. Attention to group-level dynamics enables researchers to see how a subject population collectively understands contentious or “thick concepts” (Coppedge Reference Coppedge1999). This enabled me to see that vendors understood both their victimization and resistance as multi-dimensional in nature. Attention to the interactions between focus group participants can provide insights into how social processes unfold. This allowed me to observe and analyze how strategies of resistance were collectively discussed and even rehearsed and performed by victims beyond the gaze of their victimizer.

I coordinated and carried out nine focus groups. Each had between five and seven participants, and each was balanced along dimensions of age, gender, length of time working in the market and in the informal sector, and type of merchandise or service they sold. Focus groups lasted approximately two hours and I assured participants that I would never reveal their names given security concerns. Meetings took place in a small hotel meeting room on the other side of the city. Each vendor received $15.00 (in Colombian pesos) for participating. Two longtime residents and civil society leaders from the Comuna 10 provided invaluable assistance in coordinating logistics, including helping me to identify and communicate with potential participants and arranging transportation for vendors to the hotel in ways that would avoid drawing the attention of the coordinators of the protection racket.

Second, I carried out participatory drawing exercises. I gave focus group participants blank sheets of paper, pencils, and pens, and asked them to draw something in response to the following prompt: “Please think about the place where you work every day. Now draw what you feel generates either insecurity, security, or both in this place.” Participatory drawing has been used to study how people experience and interpret political and criminal violence (Auyero and Berti Reference Auyero and Berti2015; Moser and McIlwaine Reference Moser and McIlwaine2004; Wood Reference Wood2003). Drawing exercises enable participants to exercise agency in defining part of their contribution to the research process and can help researchers elicit data on sensitive and emotional dynamics (Kearney and Hyle Reference Kearney and Hyle2004, 376). While most participants engaged in the group discussions, others remained quiet, but then enthusiastically described the meanings of their drawings to their groups (Zuboff Reference Zuboff1988, 141).

I conducted thirty-one semi-structured interviews with civil society representatives, police officers, political officials, and individual informal vendors within or in the area immediately surrounding the informal market. I triangulated data from the interviews with data from the focus groups and drawing exercises. Finally, participant observation in the informal market allowed me to observe some of the interactions between vendors and the racket’s criminal coordinators and enforcers, though I was only able to understand what these interactions meant based on the insights gleaned from the other methodologies.

Domination under the Criminal Protection Racket

The criminal coordinators of the Convivir harness negative social perceptions of the informal vendors to engage in social domination. As in other parts of the world, informal vending in Medellin is derided as a source of reduced tax revenue and urban physical disorder.Footnote 33 But local authorities also publicly link the informal vendors to the micro-trafficking of drugs carried out by the gangs that run the rackets. The vendors do not contest this reality:

We bring lots of noise and congestion and lots of things that don’t look pretty, and that helps the Convivir. It lets them hide among us, take from us, but also profit from us in other ways, selling drugs, guns, all sorts of bad things. We are like the dogs, and they are like the fleas. Where we go, they go.Footnote 34

This association fuels negative social perceptions of the vendors. One female vendor that sold used clothing lamented:

When I get on the bus from my house we drive by market. I’ll sit there and I’ll hear people say, ‘Look, these are drug traffickers. All of them are traffickers, thieves, rats.’ And I’ll keep quiet. But I am ashamed. I say to myself: ‘What a pity—that all of us have to pay for what we haven’t been. It makes one ashamed.’Footnote 35

The racket’s coordinators tap into these and other negative social perceptions to publicly humiliate the vendors. Racket collectors regularly step on the vendors’ merchandise and shove them at will—both during and apart from the collection of tribute. But the most commonly used form of humiliation is verbal insults that affirm a social hierarchy where vendors are considered desechable (disposable). Racket coordinators commonly insult the vendors’ dirty clothes, how they smell, and the fact that the vendors earn their livelihoods selling checheres (slang word for assorted trash items). As one vendor noted: “Some Saturdays they just stick out their hands. Other Saturdays they wake up on the wrong side of the bed, because they come with their foul words to make one feel insignificant. As if taking our money wasn’t enough!”Footnote 36 Another reflected on how these insults reaffirm broader social norms: “They just say what everyone in society already thinks about us.”Footnote 37

The racket’s collectors intertwine social and material domination by forcing vendors to witness the physical humiliation of their own. For example, three participants in a focus group discussed one racket collector’s favorite punishment for failure to pay the security tax:

Vendor 1 (male): We call him [the racket coordinator] the Enforcer. He likes to take people into his truck that he keeps parked right next to the market, where he has a motorcycle helmet for those moments. He hits us in the face with it and if you try to get in the back seat away from where everyone can see what is being done to you, he gets angry and hits you harder. He makes sure everyone can see what is happening to you, he wants us to see each other getting a paliza (beating).Footnote 38

Vendor 2 (male): Hitting a man in the face. Seeing that. (Vendor 2 grimaces and shakes his head.) They make us lose respect for ourselves and for each other. You have to keep your mouth shut while they do these things to you and your friends. You have to be … (Vendor 2 covers his mouth with his hand). That stays with you a long time.Footnote 39

Vendor 3 (female): That’s hard for all of us, to see that and know that we cannot move or say anything. But it’s harder for them, the men. To have to watch each other being humiliated. It demoralizes the men … all of us.Footnote 40

Members of the gang also regularly use vendors’ piles of merchandise on the ground to hide the individual doses of cocaine that they sell within the market, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2 Focus group participant drawing #1

Note: This vendor, an approximately thirty-five-year-old female, explained her drawing to the focus group in the following way: “This is me [yo] and my business [negocio]. What generates insecurity [inseguridad] for me? Lots of things. The police [polícia], the cars and motorcycles [moto] that speed by so fast. But the worst is when they [Convivir] make me hide their drugs [esconder droga]. And when they do it they insult [insulta] me, say ugly things to me [puta] (Spanish slang for “whore”). Focus group participant (MDE_FG3_550), Medellin, March 2017.

Vendors understood this as further insult to their efforts to make an honest living:

How are you going to justify taking a man’s work—the place where he earns the food for his family—and use it to sell vicio [illegal drugs]? You can’t. No one that respects you could justify it. We are disposable to everyone.Footnote 41

This is our work. Hiding the drugs in our merchandise, selling the drugs next to us—all of that is not only bad for us, because we are the ones that would suffer the consequences, it is also disrespectful to us as workers.Footnote 42

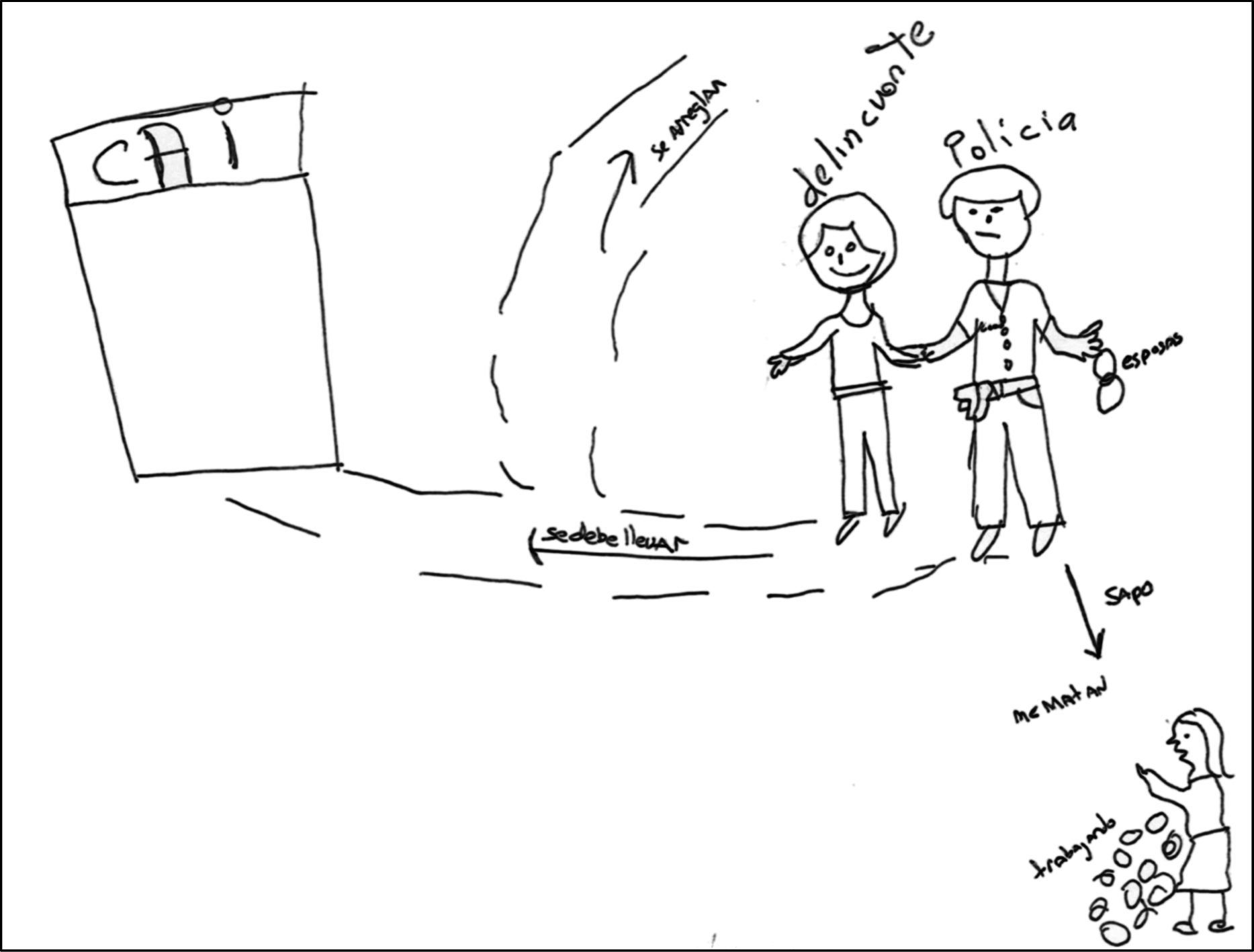

Verbal insults, humiliation woven into physical punishments, and forced complicity in drug trafficking are the social taxes incurred as part of victimization and which the conventional focus on physical offenses alone overlooks. But the criminals also impose political domination by flaunting their co-optation of the state’s local coercive apparatus: the police that patrol the market. Vendors view police as co-opted by receiving regular payments from the gang in exchange for warning them if anyone reports its illicit activities.Footnote 43Figure 3 depicts this dynamic.

Figure 3 Focus group participant drawing #2

Note: This vendor, an approximately forty-year-old woman who sold used clothing, explained her drawing to the focus group in the following way: “If I see a thief [delincuente] and tell the police [polícia], then the police should take him away [se debe llevar] to jail [or CAI, referring to decentralized police stations called Immediate Attention Commands]. But instead they will go around the corner and make a deal [se arreglan] where the police take off the handcuffs [esposas] in exchange for some money. And if the thief offers enough money, the police will tell him who reported him [sapo], and they will come to where I am working [trabajando] and kill me [me matan].” Focus group participant (MDE_FG2_01), Medellin, March 2017.

The racket’s coordinators leverage their co-optation of the police to make evident to the vendors how this power comes at the expense of the vendors’ rights and citizenship. An older male vendor recounted during an interview how one day he had not sold enough to even “pay for my bus ride home.”Footnote 44 Instead of threatening or using coercive force, the racket collector simply reminded him that he could not turn to the state for help:

“He smiled at me because they are all descarados [shameless]. And he said to me, ‘Of course, you could call the police, but even if they show up, it’s more likely that they work for us than that they’ll work for you.”Footnote 45

When physically assaulting vendors who fall behind on their weekly tribute, racket members will tauntingly tell them to “Call the police! Call the police!”—a reminder that this basic institutional resource to which the vendors are theoretically entitled to as citizens is, in practice, denied to them as part of the process of victimization.Footnote 46

Everyday Resistance to Criminal Victimization

Vendors resist their victimization. To resist material domination vendors appeal to the very asymmetry in power between themselves and their victimizers. When the racket’s agents collect their weekly tribute, vendors deliver discourses that affirm the racket’s authority but encourage benevolence.Footnote 47 As one vendor noted: “When it comes time to pay them the vacuna (vaccination, slang for the security tax) we have to become movie actors because it is better to have them as friends than as enemies.”Footnote 48 Through “acting” as resistance vendors confirm and challenge the authority of the racket’s collectors. During the focus groups several vendors recited some of the “lines” they use to this end:

You as the ones who see and know everything here must know that I haven’t sold a thing in so long. So how could I have money to pay when no one is buying?Footnote 49

Oh brother, you know better than I do that things have been tough this week. What can I do? What can I say?Footnote 50

Well, nothing moves [in the market] without you saying it’s okay. So can’t you make people move their pockets and let loose some money here?Footnote 51

Vendors admit that these scripts only mitigate material domination:

So two or three of these little boys will arrive with their chests puffed out and tell us that it’s time for our “collaboration.” But how much you pay depends on the attitude one assumes with them. Without being rude … if you make them feel like men, then they might even let you go that day without paying.Footnote 52

These performances reduce material taxation at the margins when the racket collectors allow the vendors to pay half or less of the tribute. Several vendors indicated that given their precarious economic circumstances, these reductions still represented a gain: “algo es algo” (it’s better than nothing).Footnote 53 But it is the ability to sometimes deny the criminal actors exactly what they demand that vendors see as more powerful than the marginal financial gain—a way to preserve their dignity in the face of victimization: “When you don’t give [the racket collectors] everything they want, you show them, you make them see that you are not some little dog following them and obeying them when they say ‘sit’.”Footnote 54

Vendors use rhetorical tools to resist verbal insults by framing themselves and the racket as businesses. They in turn equalize their social status in the face of their victimizers’ efforts to denigrate their position in the social hierarchy:

I tell them “no” (when the racket’s collectors verbally insult the vendors). We are in the same situation. Working on the streets, out here where nobody cares about either of us. Both of us work hard to make a living, to feed our families and to survive. We are not that different.Footnote 55

Vendors resist offenses against their dignity as workers when the racket’s members attempt to hide illicit drugs in the vendors’ merchandise. The vendors indirectly remind the racket’s members that they too are business owners to be treated with respect:

Yes, they try to extend the plaza (name given to micro-territory used for the sale of illicit drugs) into our businesses. So sometimes we find a little “package” that doesn’t belong in our things, and so with a lot of respect, we say: “Jefe [boss], the thing is, my food is at play here. Please help me and don’t hide this here.” Or if they take a chair and start selling (drugs) from right next to where I’m working, we say, “Oh, I’m so sorry, but I need the chair back for my customers.” And then you take it and they don’t have anywhere to sit. You have to make them feel uncomfortable. But also, in a respectful manner, we make our businesses get respected too.Footnote 56

They screw us by hiding drugs in our merchandise. They begin to sit around, and we see them … [crack] pipes, [crack] rocks, [crack] pipes … all mixed in our merchandise. And inside [of ourselves] we say, “Oh god, not again! People using us, disrespecting us because we’re disposable.” But on the outside, we have to walk carefully and do the dance. So we say, “Look, muchachos [boys], the thing is that everyone here, you and me, we’re all working. And this is my business. And if I get caught with your product, then it’s my business that suffers.”Footnote 57

Finally, though police complicity with the racket’s criminal coordinators prevents vendors from enlisting it to support their resistance, vendors invoke their theoretical relationship with other parts of the state to resist political domination. They do not report their victimization because they fear retribution by the criminal group and further enabling political authorities to depict the vendors as a source of criminality.Footnote 58 As one vendor indicated: “The state is always looking for reasons to paint us as criminals, even though we are not—we are only surrounded by them.Footnote 59

But the vendors do resist political domination by invoking the frames and rhetoric of the ideal-type citizenship found in the Colombian Constitution. This exemplifies what Scheingold (1974, chap. 2) calls the “myth of rights,” wherein the belief in the rights that the state formally grants, but denies in practice, can still provide a powerful catalyst for political mobilization.Footnote 60 Vendors invoke this belief in carefully worded discourses and orchestrated actions to make clear to the racket’s coordinators that the vendors reject the notion that they are second-class citizens. As one vendor noted:

They [the racket coordinators] tell us that we are trash, like what we sell. But we show them. We mobilize, we talk about rights, about the Constitution—our bible. We celebrate it while we work, talk about it, laugh about it, so that they hear us when they’re coming to collect their money.Footnote 61

I regularly observed resistance to political domination enacted through strategic, everyday discussions among handfuls of vendors about their constitutionally guaranteed right to work. One morning three neighboring vendors at the market were discussing whether the city’s Public Space office would take away their merchandise to what they sarcastically refer to as the “North Pole”—a far-off warehouse where vendors must pay large fines to retrieve their wares. The vendors complained that the legal code that gave Public Space agents this power was essentially a “law that allows the state to steal.”Footnote 62 The three vendors then noticed one of the racket’s coordinators crossing the street and approaching. “Aquí viene el duro” (Here comes the tough one), one of the vendors whispered. At that point I expected the conversation to end, but instead the vendors began talking more loudly about how the confiscation of their merchandise was a violation of their “Constitutional rights as citizens of this county.” A second stated loudly: “We all have rights, no matter how we earn [money] for our pansito (bread), carajo (fuck)!” The third vendor replied: “Even though we may not look like it, we are also citizens!”Footnote 63 I later asked one of these vendors why they carried on this way in front of a racket coordinator. He answered: “So that they remember that they are not the only authorities here.”Footnote 64 Far from an organic extension of a conversation, the dialogue had been a strategic declaration to remind the victimizer that the vendors rejected political domination as part of their victimization.

Other forms of resistance to political domination include rallies that small sub-sets of the vendors organize within the market to highlight their vulnerability to displacement by local authorities. Vendors cover light posts and cement walls with politically-infused images that reaffirm their citizenship, from tattered Colombian flags to laminated news clippings discussing previous rallies. What is analytically notable is that these regularly take place on Saturdays—the very day the racket’s coordinators tax the vendors. When I asked one of the rally’s organizers why they would do so, she replied: “We don’t have guns. We don’t have politicians. But we do have dignity and rights and this (pointing to her head), and so you need to use it to make them (the racket’s collectors) realize that they haven’t cornered us—that we are citizens.”Footnote 65

Conclusion

The conventional focus on crime as an act obscures from view the dynamic political interactions that make up the process of criminal victimization. To analyze this process I developed a theoretical framework to identify, conceptualize, and theorize how victims and criminals pursue and resist power. I illustrated the framework’s utility through an analysis of the victimization of informal vendors under a criminal protection racket in Medellin. The argument and empirical findings should motivate an expansion and deepening of the research agenda on the politics of criminal victimization, and also inform related policy efforts to stem crime and advance the rule of law.

Criminal actors do not rely solely on coercive force to carry out and sustain victimization. They instead combine efforts to extract material rents with strategies of social and political domination. The coordinators and enforcers of the criminal racket that I studied regularly and publicly insulted and humiliated vendors in ways that echoed broader social stigmatization. By making clear to vendors that they had the capacity to deny them access to the basic but fundamental right to state-sponsored security, members of the criminal racket underscored the low intensity citizenship to which the vendors are relegated. The traditional focus on the coercive capacity of criminal actors should thus be broadened to include the range of other behaviors and practices they pursue as part of criminal victimization.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, victims exercise agency in the face of victimization. Vendors used strategic and carefully worded discourses to reduce some of the material burden of criminal taxation, and to contest the disparagement of their social and economic status. Vendors met efforts to denigrate their citizenship with indirect but public expressions of political voice attesting to the vendors’ belief in their status as citizens with formally accorded rights. Everyday resistance is not a panacea for victimization, but it does enable victims to negotiate particular dimensions of their victimization and to secure some material and non-material gains.

A key task for future research is to conceptualize and theorize the range of strategies victims pursue in response to criminal victimization. Albert Hirschman’s (Reference Hirschman1970) exit, voice, and loyalty framework could be a point of departure to analyze why populations facing similar forms of victimization pursue varied responses. For example, since the start of Mexico’s war on drugs in 2006, some business owners in Ciudad Juarez have opted for the “exit” option—closing their shops and migrating to the United States—in the face of violent criminal protection rackets. Other business owners in the same city have chosen to exercise “voice” by working with government authorities to weaken the rackets in the micro-zones where their businesses are located (Morales, Prieto, and Bejarano 2014). Meanwhile businesses in parts of Eastern Europe seem to have favored “loyalty” to rackets that offered security and order.Footnote 66 Such puzzling cross-regional and subnational variation offers fertile terrain to study why victims select distinct responses when confronted with similar forms of criminal victimization. The resulting insights could help policymakers build constructive forms of public-private collaboration to stem crime and advance the rule of law (Arias and Ungar Reference Arias and Ungar2009; González Reference González2017; Moncada Reference Moncada2009).

If resistance is the way that victims of crime exercise voice, then a second challenge for future research is to explain why resistance can vary in dramatic ways. A first step here is to develop typologies that capture the theoretically salient differences across distinct forms of resistance. While the informal vendors analyzed in this article engaged in everyday negotiations with their victimizers, in parts of El Salvador, victims of protection rackets coordinated by powerful criminal gangs collude with elements of the police to carry out extra-judicial violence against their victimizers (Cruz Reference Cruz2010). By contrast, victims of protection rackets overseen by drug trafficking organizations in Mexico’s violence-plagued state of Michoacán have established armed self-defense groups. Why does resistance sometimes entail large-scale and sustained collective mobilization, and other times consist primarily of intermittent actions by individuals and small groups of victims? Why do some victims mobilize to end their victimization while others seek only to negotiate different aspects of their subordination at the hands of criminal actors? In addition to differentiating forms of resistance by the intent of the victims and their level of collective action, we also need to consider variation in the role of the state. One strategy here is to relax the theoretical framework’s scope condition regarding the state’s availability to support resistance.

Victims do not always face zero-sum situations where they must either turn to the state or directly confront their victimizers. As historian Elizabeth Dale (Reference Dale2011) argues, during the late eighteenth century construction of the coercive and punitive capacities of the U.S. state, citizens appealed to aspects of the emerging formal criminal justice system that favored their interests and rejected those that did not, but more often combined both with “popular justice” against their criminal victimizers.Footnote 67 What explains variation in the role the state plays in the distinct forms of resistance that victims pursue?Footnote 68 Research along this line could inform policy efforts to prevent extra-judicial violence in settings of intense crime and insecurity.Footnote 69

My analysis also highlights the need to explore the relationship between different forms of resistance, the targets of resistance, and the conditions under which resistance succeeds. Can victims pursue both violent and non-violent forms of resistance against the same criminal actor? Do victims engage in everyday and other forms of resistance against the state given the prevalence of both lethal and non-lethal forms of criminal behavior by police in diverse settings, from Chicago to Rio de Janeiro? Finally, further study is needed to identify and theorize the ways in which criminal actors respond to distinct forms of resistance. When do criminal actors capitulate in the face of resistance? And when and how do they fight back? Research along these lines will help to advance our understanding of criminal victimization and related concerns in the growing field of criminal politics.