Part III The Role of Uncertainty

4 When uncertainty increases cooperation

We can observe collective action or a lack of collective action between firms and parties depending on the breadth of networks and the level of uncertainty. I now explore this argument through party finance, because a major form of collective action between firms and parties takes place when firms finance party political campaigns in exchange for support.

Parties and firms both have reasons to pursue financing arrangements. Parties seek to maximize financial support to increase their political advantage. Firms’ financing of campaigns constitutes an investment geared toward obtaining favors from the winner. A firm’s decision to finance depends on (1) the likelihood of identifying the winner (which in turn depends on the degree of electoral uncertainty) and (2) the likelihood that the receiving party, if it wins, will actually deliver on the promise of favors once in office. The mechanism behind the second condition brings in the role of network density. The winner is compelled to deliver on a promise of assistance to the firm that supported the campaign if shirking can easily be detected and punishment ensues. Network density favors this outcome, because information flows rapidly, reputation mechanisms can operate, and a collective response can mobilize. Broad networks, in other words, make the informal and often hidden contracts behind party financing more enforceable. Firms feel more confident about supporting parties, and parties pay back by delivering favorable policies in order to maintain future streams of support.

When broad networks are combined with high uncertainty, as happens in Poland, the result is a virtuous form of collective action, which I call “concertation,” and we observe the winning party exercising responsiveness to its supporters through broad distributive policies. Concertation sustains cooperation between parties and firms by facilitating the enforcement of agreements. In particular, political uncertainty presents parties with the threat of losing at the polls, and thus provides an incentive to pay back firms once elected or risk losing in the following election. Broad networks provide an effective flow of information among firms, which are therefore more able to avoid parties that shirk on their campaign promises. The two factors together mean that pre-election agreements are secured by both the threat of noncompliance and the monitoring allowed by effective information sharing.

The result of this cooperation over time is the development of broad distributive policies, for two reasons that are also related to political uncertainty and broad networks. The first focuses on the supply side. Political uncertainty means that parties will seek financial support from an ever larger number of firms as they face the costs of sharp competition. As the number of supporters increases, parties have an incentive to provide their payback not in the form of innumerable selective handouts but in generalized, business-friendly regulation that will appease a broad constituency. This solution is more cost-effective and more defensible at the polls. The second reason why broad policies emerge from this configuration rests on the demand side. As examined in earlier chapters, broad networks in Poland (with a heavy presence of financial actors) imply that firms have cross-sectoral stakes and, therefore, preferences. Hence, regulation that is generally business-friendly is in demand by firms in this configuration.

The workings of political uncertainty are different when networks are narrow. When elections are uncertain but networks are narrow, the winning party cannot credibly commit to campaign promises, because defection will go undetected or unpunished by supporters. This is the situation in Bulgaria. The result is the impossibility of cooperation between firms and parties.

Finally, when political uncertainty is low and networks are narrow, as in Romania, the dominant party wins election after election and there is low expectation of a turnover of power. Because networks are weak, the dominant party is in an extremely strong position, as firms lack not only the incentive but also the means to coordinate any leverage against it. Hence, the dominant party exploits them for financial support, and firms are in a position of subjugation: they know that they need to support the dominant party if they are to hope to receive support and if they wish to avoid punishment, and the result is a clientelistic relation between parties and firms, and a patronage state.

What binds parties and firms?

Poland: stable party–business alliances

The case of Poland shows how high uncertainty and broad networks promote cooperation. Because uncertainty in Poland meant political alternation, the left and the right competed for supporters. The result was that both political sides developed a network of powerful and loyal contributors. In the short run, the arrangement required significant and individualized handouts to key supporters when each party was in power. In the long run, however, as more and more firms in the country picked one side with which to align, the result was two increasingly broad and dense networks. Hence, over time, dynamic governing-party–firm relations moved from a prevalence of individual handouts to a prevalence of broad distributive institutions better suited to sustainably addressing the claims of the respective widening support coalitions. It is precisely the “arms race” derived by political uncertainty that promotes the alignment of increasing numbers of firms to one of the two political sides. The analysis of the Polish case below focuses on the early phase of individualized handouts to large backers. Evidence of the progressively higher rates of broadly distributive institutions is presented in Chapter 6, which discusses the impact of state types on governance.

The pitched competition between post-communist and anti-communist forces shaped the nature of political financing and reinforced the dynamic of strong links between political and economic actors that began to take shape right after 1989. It is still widely believed that the former Communist Party elites who seized economic assets as they transformed themselves into post-communist politicians were largely responsible for the promotion of insiders to prominent places in the business world (Solnick Reference Solnick1998; Gustafson Reference Gustafson1999; Staniszkis Reference Staniszkis2000). Poland provides new evidence against this view, as parties that emerged out of the Solidarity movement were also repeatedly involved in scandals related to contacts with business. In fact, influenced by the sheer number of scandals, the public believed in 2000 that post-Solidarity politicians were far more corrupt than the post-communists. During the government of Jerzy Buzek (1997–2001) an unrivaled twenty-two ministers were dismissed, many as a consequence of corruption.

As this suggests, politicians in post-communist Poland have frequently attempted to exert influence over public and private assets. Their interest in these assets stems from a need for financing in order to retain power. Critical packets of extra money originated from political allies in large business in the form of a-legal donations (known as cegiełki, or “bricks”) and free business services. Although these contributions were clandestine, available evidence confirms the importance and magnitude of covert contributions by firms and how the process of undocumented party finance was supported by a deficient legal framework governing party finances and poor monitoring and enforcement (Walecki Reference Walecki2000). Walecki (Reference Walecki2005) offers an excellent discussion of the shortcomings of the laws regulating political parties and the bureaucracies charged with monitoring them. Walecki (Reference Walecki2005) and (Reference Walecki, Smilov and Toplak2007) highlights the role of plutocratic funding, the failure of parties to provide election expense returns, and the lack of adequate policing throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

Few factors seem as important as personal ties in explaining which firms contribute to which party. This can partly be attributed to the fact that the programmatic differences on economic policy between the leftist SLD and the rightist AWS were narrow (Brada Reference Brada1996).1 On industrial policy, political views had little meaning, since the room for fiscal expenditures was thin and budgetary demands pushed privatization and restructuring to the top of the policy agenda. Conversely, some issues were too prickly for discussion by either end of the political spectrum. For example, in 2000 no political faction would have dared to privatize Polish sugar. Even the last AWS and strongly pro-privatization minister of the treasury, Aldona Kamela-Sowińska (known as the “Iron Dame”), backed down from this proposal in the Council of Ministers.

In the context of intense competition and a long-inadequate system of official financing for parties, alternative strategies of campaign finance became commonplace shortly after 1989, when parties had access to assets that came from unofficial sources. For example, the Centrum Alliance (PC) was formed in 1990, and its source of financing was to be a newly registered company called Telegraf. The firm’s worth grew many times over, and this contributed to the PC’s subsequent development into one of the three large Polish parties (Walecki Reference Walecki2000; Paradowska Reference Paradowska2001). The Kaczynski brothers, who reshaped Polish politics in the 2000s, were early activists in the PC.

Once in place, the situation proved hard to reform. It persisted partly because regulations failed to provide adequate means to stamp it out, and parties have not found it in their interest to design a more stringent framework for oversight. The Law on Campaign Financing of 1997 provided no means of supervising party financing other than declarations submitted after elections.2 These are so general that it is hard to verify the size of donations. No disclosure was required of political donors, and only parties are required to provide reports summarizing their finances. Furthermore, no sanction is specified for violating the law (Walecki Reference Walecki2000: 86). This created a broad system of financing parties through firms, including state-owned firms (Walecki Reference Walecki2000: 113). The situation changed somewhat after 2000, when a system of broad public financing was introduced. It did not address the issue of the disclosure and monitoring of party finances, however. It simply added another layer of financial inflows that exists in parallel to illicit financing. Instead of decreasing the competition for funds, it has left Poland with a situation that Ikstens, Smilov, and Walecki (Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001) describe as a party finance “arms race.” According to Szczerbiak (Reference Szczerbiak2006), electoral finance appears in the form of the direct financial support and indirect state subsidies that parties receive, but both types are supplemented by forms of patronage through the appointment of party loyalists to state and quasi-state bodies, such as state-owned or partially privatized firms.

In this context, the left political parties assisted in the formation of a group of entrepreneurs who have been their strong supporters for much of the post-communist period. These ties brought financing to the left, but were openly portrayed as a political effort to create a domestic class of entrepreneurs in the face of intense foreign competition. This group included men such as Gudzowaty, who became a billionaire in dollars for his role as an intermediary in the import of natural gas to Poland.3 In exchange, Gudzowaty received vital support to expand his firms beyond gas supply. Rightist political parties perceived him as a stable ally of the left. According to his allegations, right coalitions in government were aggressive in their attempts to intimidate and dislodge him, allegedly even using the secret police.4

Other businesspeople also developed strong contacts with leftist parties that were vital to the success of their business. Among these was Piotr Bykowski, a rising member of the Communist Party until 1983, when he declined a job in the central committee of the Poznan region and left the party as an “unreformable organization” in order to become a capitalist (Gabryel and Zieleniewski Reference Gabryel and Zieleniewski1998). His banking empire was created with the support of left parties. In keeping with Bykowski’s idea that “state bureaucrats are obligated in helping to create new economic solutions, which will serve society” (Gabryel and Zieleniewski Reference Gabryel and Zieleniewski1998: 168), Bykowski placed many former government officials on his supervisory board. As an aide to Waldemar Pawlak, the socialist prime minister from 1993 to 1995, he worked closely with two ministers of foreign economic cooperation and persuaded the government to establish an institution granting export credits and supporting trade with the West. Effectively, this was an attempt to have the SLD–PSL government build a financial empire with government capital. The program was halted later by Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz when he was prime minister (1996–7). Bykowski’s Bank Staropolski declared bankruptcy in 2000 after Bykowski was arrested for allegedly transferring $500 million of the bank’s funds abroad.

The left was not alone in creating and promoting a group of loyal entrepreneurs. The post-Solidarity groupings also had their protégé businesspeople. Like the SLD, the right attempted to cast the behavior of the political class toward firms as being not purely about economic gains. The interest in and need to create ties to the economy was critical in light of the sharp political struggle with the SLD. The support of domestic entrepreneurs also became an integral part of the discourse of economic development proposed by the right, however. One of the most visible individuals involved in this policy was Jan Kulczyk.

In 1993 Kulczyk, vice-president of the Polish Business Roundtable, the most elite business organization, suggested that Polish entrepreneurs should be able to buy SOEs with payment plans extended over many years. Upon receiving an entrepreneur’s award in 1992, Kulczyk said, “I believe that Polish firms should remain in our hands. Instead, selling domestic capital to foreign firms should be a way of filling out privatizations” (Gabryel and Zieleniewski Reference Gabryel and Zieleniewski1998). Again, the comments of the Democratic Union (UD) minister of privatization at the time, Janusz Lewandowski, testify to the concern with domestic development: “We decided on preferences, for example, payment in parts over time. This was a conscious choice against the best offer. Western groups have a tremendous advantage over us. Privatization created an opportunity for the rise of domestic groups” (Gabryel and Zieleniewski Reference Gabryel and Zieleniewski1998). Hence, when Lewandowski put 40 percent of Lech Breweries on sale, he announced that only Polish business could take part. Kulczyk won the tender through his firm Euro Agro Centrum, and thus established his relations with the center-right coalition then in power. All Kulczyk’s major deals – Lech and Tyskie Breweries, TPSA, Autostrada Wielkopolska – were concluded under right-leaning governments. He had such access that some transformed his name from Kulczyk to kluczyk, the Polish word meaning “key” (Solska Reference Solska2012). Later that year the post-communist SLD returned to power and decided, through the Ministry of the Treasury, to raise the capital of the firm. Subsequently, the Treasury decided not to buy any new shares. Kulczyk, lacking capital, was forced to find an outside investor (South African Breweries). Thus, the SLD government succeeded in undermining Kulczyk’s control of the company (punishing him for his affiliation with center-right parties) and limiting the distributional consequences of the deal.

Individual businesspeople who cultivated relations with political elites held massive fortunes but accounted for only a portion of business support. The privatization process, which often only partially privatized firms, enabled the political appointment of selected directors and managers to newly private companies. These directors and board members, often selected from the ranks of poorly paid but politically faithful bureaucrats, became loyal backers of their political sponsors. Banks also became a critical chip in the Polish post-1989 game of wealth accumulation by political actors. The struggle over their control and the involvement of national political figures, including the second Polish president, Aleksander Kwasniewski, illustrate the centrality of the struggle to control property and its connection to the political struggle between the communist successor parties and the Solidarity/post-Solidarity coalitions. Simultaneously, the race to appropriate assets for the national political contest also created the major banking institutions in Poland.

Throughout these moves, parties and firms became tightly allied partners in the struggle to increase revenue on both sides. There is an important distinction to be made between the race to control assets and the attempt to manage them, however. Parties did attempt to politicize firms but they did not seek to interfere in their management. Describing the interaction with parties in an interview, one businessperson used the phrase “They govern but they don’t manage” (Rzadza ale nie zarzadzaja) to express the perception that parties did not have a coherent plan of firm development. What they sought was a reliable stream of revenue as part of a mutual exchange. This outcome was strikingly different from that of Romania and Bulgaria.

Romania: the state against firms

Romania displays low uncertainty and narrow networks, a combination that results in a patronage state. Party finance in Romania offers a potent and contrasting example of how the level of party competition structures the ability of parties to extract funds, and shapes firm incentives to finance political parties. Whereas parties in Poland were engaged in a sharp conflict between alternative ends of the political spectrum, Romania’s post-transition political history can be summed up as a period of rule by a group of elites emerging around the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. These elites founded the National Salvation Front, which underwent several splits into competing factions. One of these factions, the Party of Social Democracy of Romania, eventually became the Social Democratic Party in 2001. President Iliescu and the PDSR/PSD dominated Romanian politics until the Romanian Democratic Convention was elected in 1996 – the first time that an opposition party was able to form a democratic government following success at the polls. The CDR was voted out of office after one term, however. Although there have been numerous splits and recompositions of individual political parties, the range of alternation is without question much narrower than in Poland or Bulgaria. In this context, the general situation of Romanian party financing leaves much to be desired. Regulations demand that a list of persons who have donated more than the equivalent of ten times the minimum wage must be published. This regulation is not enforced, however, and some parties, such as the Party of Social Democracy of Romania, never published such a list despite numerous scandals about illegal financing. The Liberal Party also never published these financial statements (Ikstens, Smilov, and Walecki Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001).

With such lax monitoring, Romanian political parties are able to aggressively seek out donations. In fact, in an interview one party official argued that “the main problem of party finance is to begin to apply the laws of party finance, not to create new ones.” In Romania, flaws in party finance laws are also intensely exploited by parties to receive funds from the state and private donors. These included the awarding of lavish public contracts to campaign sponsors and large-scale patronage to reward important donors (Gherghina, Chiru, and Casal Bértoa Reference Gherghina, Chiru and Casal Bértoa2011: 22) According to Roper, Moraru, and Iorga (Reference Roper, Moraru, Iorga, Roper and Ikstens2008: 150), “The lack of transparency has led in certain cases to the transformation of the party’s finances into a private business. This mechanism starts with the charging of ‘fees’ for candidates that are not reported, the obtaining of contributions that remain undeclared and the conclusion of contracts with companies owned by party members.” Matichescu and Protsyk (Reference Matichescu, Protsyk, King and Sum2011) argue that business elites are prominent on party lists as part of a system of clientelistic exchanges that provides parties with electoral funds and businesspeople with protection of their interests and, potentially, immunity from prosecution. They also point out that this dynamic has become stronger over time. The percentage of parliamentarians with a business background steadily increased in the period from 1990 to 2004 (Protsyk and Matichescu Reference Protsyk and Matichescu2011: 214). The use of a closed-list proportional representation system until 2008 reinforced the ability of political party organizations to use positions on the party list to obtain campaign funds (Matichescu and Protsyk Reference Matichescu, Protsyk, King and Sum2011). While we might expect an electoral reform to disrupt the ability of parties to trade seats in parliament for funds, the introduction of single-member districts had a minimal impact on the power of party leaders (Coman Reference Coman2012).

To illustrate the Romanian dynamic of party finance, consider the following example: on November 15, 2003, PSD secretary-general Dan Matei Agathon announced in Botosani that the party had just 20 percent of the funds it needed to finance its upcoming electoral campaigns, according to the dailies Adevarul, Evenimentul Zilei, and Romania Libera (reported on November 17). Agathon said that party officials who wished to retain their current posts should immediately embark on securing the needed funds, keeping in mind that they would be judged by their performance. He added that prospective candidates had to contribute to the PSD’s electoral funds. Those candidates would have to raise campaign funds from private companies, to which they were to make clear that they could not finance other political parties at the same time.

Romania thus followed a quite different path, and firms there occupy a much more subordinate position than those in either Poland or Bulgaria. The comments of the PSD secretary-general offer an insight into the relationship between business and political parties in post-socialist Romania. The dominance of post-NSF elites created a rather surprising dynamic. Although Romanian politics was marked by a series of splits and party divisions among the group of elites that formed the initial National Salvation Front, these can be seen as conflicts within a narrow clique struggling for executive power. In this context, the left–right split is quite blurred, and parties that opposed each other in one election often became allies in a coalition government only a few years later. For example, between 2005 and 2008 the PSD was an opposition party after losing an election to a coalition comprised of the Democratic Party and the National Liberal Party (PNL). After various factional conflicts, the PD changed its name to the Democratic Liberal Party (PD-L). In 2008 the PD-L formed a coalition government with its former opponents, the PSD.

Strong expectations of dominance on the part of the post-NSF groupings conditioned business to seek ties primarily with politicians from these parties, but failed to create the conditions for lasting alliances as the dominance of a single party made firms vulnerable to extraction. The long success of the PSD gave it an advantage in this search for financing. A business leader noted, “The PSD has the most of them, contributors, because there are many people who are benefiting from favors from them. It is not possible for a big businessperson to prosper without political connections.” The relationship between parties and firms was different from the partnership that had developed in Poland: business leaders had much more of a sense that parties had the upper hand in the relationship. Another top business owner observed, “We are providing a significant portion of the state revenues and they have to understand that they have to consult my business. But they don’t. They are the rulers and they expect the subjects to contribute.”

As a way around this dilemma, some powerful businesspeople tried to become major figures associated with a particular, personal, party. The oil magnate Dinu Patriciu has, for example, long been involved with the Liberal Party. In fact, he was one of the founders of the party, and worked to develop a political career at the same time as he was developing his fortune. Others established what could best be called vanity parties, such as the Humanist Party of Dan Voiculsecu. This was essentially a personal vehicle through which to lend support to the PSD while also obtaining some security.

The remaining companies try to follow a “swinging” pattern when political opportunity presents itself, jockeying for favor from a member of the dominant coalition, which has thus far meant figures from the various centrist groupings of post-NSF elites. Hence, the difficulty that the opposition faced in gaining seats was related to the fact that it also had a difficult time raising funds. It searched for economic allies among firms that were unable to attract the protection of the PSD, often at an exorbitant cost.

This pattern was documented in a White Paper issued in May Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001, in which the government of Adrian Năstase charged the opposition CDR for allowing arrears to grow rapidly and using concessions to favor particular interests. According to the White Paper, debts to the Finance Ministry stood at an overall lei 7,393 billion at the end of 1996, before the CDR took power. Concessions accounted for only 10.6 percent of this debt. In contrast, the value of debts at the end of the CDR mandate, in 2000, was estimated at around lei 60,000 billion, with concessions related to 60 percent. Debts to the Work and Social Security Ministry at the end of 1996 were worth lei 3,671 billion, and by the end of 2000 they had surged to lei 45,000 billion, of which concessions accounted for 15 percent (Government of Romania 2001). This dynamic, according to the White Paper, was the result of the restrictive economic policies followed between 1997 and 2000, which had led to the “rapid de-capitalization of economic agents coupled with a surge in their indebtedness to creditors” that was tolerated by the CDR.

The White Paper was highly criticized by the opposition as a political smear campaign that attempted to place blame on the CDR for difficulties facing Năstase’s new government. Yet, if the data are reliable, they suggest where the CDR’s support lay within the economy: firms dependent on concessions that had not been able to obtain them under previous governments, and firms awarded concessions in an attempt to secure their future support and lure them away from the PSD.

Outstanding payments in the state sector diminished to the equivalent of 26.8 percent of GDP in the first half of 2000 from a high of 39.6 percent of GDP in 1996, during the CDR government. As the CDR’s support did not come from this sector, it was able to call in the debts of large state-owned enterprises. In contrast, in the mixed-property sector, debt grew to 33.3 percent from 20.4 during the same period (Government of Romania 2001), reflecting the need of the CDR to offer more slack to such firms. A similar explanation could be offered for the rise in concessions. Combined with this first observation, the steep rise in concessions between 1997 and 2000 at the Finance Ministry and Ministry of Work and Social Security was a sign of the importance that giving out this form of preferences to private business held for the CDR. As the NSF and PSDR drew their support and finances largely from the state sector, they did not need to offer concessions to private firms.

Unsurprisingly, the PSD was able to leverage its political dominance into greater access to gains from illicit financing. Extracting money from the state sector was a key means of obtaining support. One method, for example, was for firms to place advertisements in newspapers. The firms would pay newspapers for “advertising,” and the latter would funnel money to political parties. A telltale sign of this dynamic was when advertisements promoted unusual sectors. For example, a business leader pointed out in an interview that the control tower at Bucharest’s Otopeni airport ran an advertisement despite the fact that it had no competition and there was no choice in the use of its services.

Over time, the dominant party was also able to attract well-known politicians. In the period leading up to and right after the 2000 electoral defeat of the CDR coalition, a series of senators and deputies migrated (Stiri Politice 2000). This mostly meant a move to post-NSF splinter groups such as the PDSR/PSD. Thus, Adrian Severin, Adrian Vilău, and Octavian Stireanu left the PD for the PDSR, the last giving up his seat in the senate for a deputies’ seat. Similarly, George Pruteanu left the Christian Democratic PNTCD for the PDSR. Valentin Iliescu left the PUNR for the PDSR. Adrian Paunescu left the PSM for the PDSR. Triţa Faniţa was the leader of the PD and switched in 2000 to the PSD.

The lower degree of uncertainty in Romanian politics as a result of the dominance of the Social Democrats created a situation in which firms were unable to count on political alliances. The dominance of the Social Democrats also created a spiral of increasing support, as confirmed in the extent of party switching. As a result, there were none of the alliances between parties and firms that were such a central part of the Polish landscape.

Bulgaria: firms against the state

The case of Bulgaria displays high uncertainty and narrow networks, resulting in an inability to coordinate and in the prevalence of preying and violence against the state. Bulgarian politics since 1989 has been marked by instability and contention over basic reform issues. The Bulgarian Socialist Party (formerly the Bulgarian Communist Party) won the first post-communist parliamentary elections in 1990, with 48 percent of the vote and 52 percent of seats. The BSP’s support was drawn from pensioners, peasants fearful of land restitution, and the technical intelligentsia. However, the BSP’s policies were largely driven by the old nomenklatura. Its official platform consisted of support for reform, but at a gradual pace.

After a series of failed attempts to form a coalition, the “go it alone” government of the BSP leader, Andre Lukanov, lasted only until late 1990, when it fell as a result of a general strike. A transitional coalition government comprised of members of the BSP, the Union of Democratic Forces, and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BANU) – a party built on the platform of agricultural property restitution – replaced it.

The country’s first fully democratic parliamentary election, in November 1991, resulted in a near-majority for the anti-communist and pro-reform UDF. A coalition government led by the UDF in partnership with an ethnic party, the Turkish Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF), was formed. Despite the passage of a privatization law and a foreign investment law, this coalition collapsed in late 1992 under a vote of no confidence and pressure from the Bulgarian president, Zhelyu Zhelev, also of the UDF. A compromise produced a government of experts put forward by the MRF and supported by the BSP and a breakaway faction of the UDF. This government became increasingly unpopular, culminating with the crash of the Bulgarian currency, the lev, in 1994, which forced the resignation of the prime minister.

The BSP won an absolute majority in the pre-term election in December 1994, with the support of the Bulgarian Business Block (BBB), a new force in Bulgarian politics that proposed to fight for the interests of small business, offering a nationalistic message. The BBB’s leader, Georges Ganchev, became a popular candidate during the 1996 presidential election. The BSP was heavily allied with newly emergent “nomenklatura”-based economic interests, with links that often ran directly to senior party officials. Despite a public commitment to macro-reform, these behind-the-scenes conflicts of interest led to reform inertia. Ganchev remained in office until February 1997, when a populace alienated by the BSP’s failed and corrupt government demanded its resignation and called for a new general election.

The crisis caused tensions among factions within the BSP. At the 1998 party congress, a faction known as “the generals,” a reformist grouping of post-communist businessmen and former security officials determined to re-establish the party, cleared the top party ranks and installed Georgi Purvanov as leader (BTA 1998c; East European Constitutional Review 1998). Little was heard of “the generals’” movement after the financial crisis wiped out many of their businesses, but Purvanov’s presidential victory in Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001 strengthened the position of the BSP. “The generals” themselves moved to take over a number of companies making light firearms and armaments, one of Bulgaria’s strong export product categories.

Once again, a caretaker Cabinet emerged, appointed by the president. Stefan Sofianski, Sofia’s UDF mayor, became prime minister. By stabilizing the lev, proceeding with privatization, fighting corruption, driving down inflation, and vigorously purging the bureaucracy, Sofianski’s government gained popularity, serving until a pre-term parliamentary election in April 1997.

In the general election that year, a pro-reform coalition, the United Democratic Forces (UtdDF), led by the Union of Democratic Forces, won 137 out of 240 seats – a landslide victory. (Other members of the UtdDF included the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union, the Democratic Party, and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party.) In contrast, the Bulgarian Socialist Party dropped from its 1994 majority of 125 seats to fifty-eight. Along with the Ecoglasnost Movement and the Aleksandar Stamboliyski faction of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union, the BSP stood as a member of the Democratic Left electoral alliance. The UDF leader, Ivan Kostov, formed a government that pushed ahead with privatization, signed a three-year agreement with the IMF, and set up a currency board.

Mounting public concerns about corruption caused the UDF to lose popularity as the July Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001 parliamentary election approached, however. As one official put it, “In the previous [Kostov] government, deals were made against the interest of the state. There is no evidence of payments but either the person making these deals was stupid or there was a financial incentive.” The Bulgarian political scene was again disturbed with the entrance of the National Movement Simeon II. This also upset already weak party–economy ties, according to an official who said, “The arrival of Simeon (Sakskoburggotski) has destroyed the clear ties along left–right lines and reconstructed them for his party.” The SNM won the general election and formed a coalition with the MRF. This government again lasted only one term. In 2005 the Socialists attempted to form a coalition government with the MRF, but its proposed Cabinet failed to receive parliamentary approval. Ultimately, a grand coalition of the Socialists, the SNM, and the Turkish minority party emerged. The parliamentary election of 2009 led to even more changes in the party system. The most votes were obtained by a new party, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, led by the brash Boyko Borisov, whose career ranged from security policeman to interior minister and mayor of Sofia. The formerly ruling SNM did not even reach the 4 percent threshold and thus obtained no seats.

This shifting party system also had an impact on patterns of party finance. Despite a law on party financing delivered at the roundtable talks in 1990 and a replacement of this law with a new one on March 28, Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001, financing irregularities are the norm. Official sources include public subsidy, own means, and income from assets and donations. Officially, anonymous donations can be equal to up to 25 percent of the public subsidy, which is determined for each election. The use of anonymous donations was seen as a major problem; as one politician noted, “The problem with party finance is that the audit mechanism is not very strong and there are still [speaking in 2003] anonymous donations.”

Balances of official party financing are available to the public, but BBSS Gallup International estimates that more than 80 percent of party finances are “non-transparent” and illegal according to the reporting standards of the law (Alexandrova Reference Alexandrova2002). According to the World Bank, 42 percent of Bulgarian companies have paid money to political parties in return for favors. This situation is allowed to persist because no effective means for the supervision of party finances exists, and officials are effectively unable to do more than rubber-stamp party financial statements (Ikstens, Smilov, and Walecki Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001). According to one official, “The real problem is that the available money is dirty money, which is controlled by people in the business community involved in the black, grey and even the regular economy.” As a consequence, another official concluded, “Many parties were using practices that ranged from the grey economy to plainly illegal practices to fund their campaigns.”

The prevalence of illegal party finance in Bulgaria reflects a larger dilemma: the fact that a group of strong societal interests faced an unstable party system. In this context, political actors were more dependent on a small group of firms than the firms on parties. Describing how parties are impacted by the business elite, a party leader said, “Most parties are infected by big businesspeople. The parties need to reform themselves and stop taking money from the grey economy.” Echoing these sentiments and pointing out that they have deep consequences for institutional development, an analyst noted, “The individuals who control the shadow business world persist in their activities undisturbed. Really this is a chain of corruption, which permeates all parties. Unfortunately, the Democrats are as corrupted as the Socialists, perhaps even more.” Moreover, narrow networks meant that economic actors beyond these small groups had a difficult time mobilizing coalitions. Monitoring through networks was weak, as well. High levels of uncertainty and narrow networks made it difficult for parties to make credible commitments to firms and for firms to monitor the fulfillment of electoral bargains.

Firms and parties in Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria

In each country, the incentives for firms to be loyal to a particular party were shaped by the extent to which firms could estimate the future political success of a potential political partner and the likelihood that favors would be delivered once in office. In both Poland and Bulgaria, the political climate created uncertainty for firms, yet, in the Polish case, broad networks allowed reputation mechanisms to operate. As a consequence, firms eagerly gave to their favorite political side, because the latter could credibly commit to delivering favors. These were initially destined for a small circle of large backers. Over time the high level of political uncertainty and electoral competition caused an increasing number of firms to align themselves. As a result, parties distributed not only selective handouts but increasingly also broadly distributive regulation. By contrast, in Bulgaria, uncertainty combined with narrow networks undermined the ability of parties to enter into credible agreements with firms. The result was a lack of cooperation and firms engaging in open preying on and violence against the state. Finally, in Romania, the dominance of a coalition meant that firms were at the mercy of political elites who controlled the state.

1 Despite the narrow differences in policy, these parties were organized around a sharp post-communist versus anti-communist ideological cleavage.

2 In 2000 campaign financing regulations restricted the types of contributions that could be accepted. Restricted sources of funding for presidential campaigns were defined in the law of May 25, 2000 (Dziennik Ustaw nr 43, poz. 488). Parliamentary campaigns were reformed on May 16, 2002 (Dziennik Ustaw nr 46, poz. 499). Political party financing was reformed in the law of July 31, 2001 (Dziennik Ustaw nr 79, poz. 857).

3 Although Gudzowaty has been a strong, open supporter of left politicians, he was also a major contributor to Wałesa’s political campaigns. Gudzowaty insists that his support for Wałesa was an indication of his enthusiasm for a man who brought about the end of communism in Poland.

4 Gudzowaty discussed the aggressiveness of right governments in an interview cited earlier.

5 Tracing elite career networks

This chapter builds on the political backgrounds and varying contexts of uncertainty presented in Chapter 4. Through a macro-level analysis of the career networks of elite state officials, it provides an empirically grounded theory of the interplay of uncertainty and networks in institutional development.

Scholars have examined the impact of different forms of embeddedness in accounts of the state’s ability to govern the economy (Wade Reference Wade1990; Evans Reference Evans1995; Kang Reference Kang2002). This chapter, however, offers one of few studies that use data to understand the role of networks between state officials and the private sector. As the coming pages show, these cleverly forged relations are only partly shaped by the individual ambitions of bureaucrats. Political parties also view the deployment of party members to other sectors as a way of creating relational assets that are important in securing political finance for parties and creating lasting bonds with firms. These maneuvers, in combination with the level of political uncertainty, generate different elite networks. As in the case of ownership networks, over time Poland developed the broadest elite network, whereas Bulgaria’s and Romania’s networks were both much more narrowly connected.

How elite networks function

Across the post-socialist landscape, poorly paid bureaucratic positions are seen as a stepping stone for talented individuals on their way to the private sector. For example, the former head of the Bulgarian Parliamentary Energy Committee, Nikita Shervashidze, was influential in the signing of a controversial contract between the state gas monopoly Bulgargas and two companies owned by Multigroup, the company that has been described as a “state within the state” for its ability to evade official control (Ganev Reference Ganev2001). As a result of this contract, Multigroup’s companies performed financial services that involved transferring Bulgargas’s receivables from two other large state companies, Chimco and Kremikovtsi, to itself. Shevarshidze subsequently left his government post and founded the National Gas Company, affiliated with Multigroup, and initiated the establishment of the Energia Invest privatization fund, which has acquired assets in a number of companies from the power industry through mass privatization.

Some authors have suggested that the post-communist left was better placed and more skillful at creating such networks (Staniszkis Reference Staniszkis2000). This is not substantiated by the historical record, however: the Bulgarian Socialist Party’s conservative rival, the Union of Democratic Forces, also created a network through which it could control economic resources. Once the UDF gained control of the government in 1997, it began to introduce management–worker partnerships in a large number of Bulgarian state-owned companies as part of its privatization strategy. As part of this policy, the UDF managed to change the directorates of several companies and installed directors who were party allies or top members of the party. This move, according to the standard argument, was necessary to prevent the mismanagement of state-owned firms by former socialist managers. The main goal, however, was to remove firms from the political control of the Socialist party. Interviews with politicians of various parties reveal that this did not mean that the firms became depoliticized property; rather, in short order, firms were sold to the RMDs and became sources of UDF donations. The pressure to compete for economic resources with other parties meant that having politically connected managers in place was key to the activities of all political parties. Commenting on the view that these networks were a resource for parties even after the individuals left formally political postions, a politician observed, “The UDF elite is still here. And the BSP elite is still here. For example, after the UDF government a lot of the UDF people went into the high court, the constitutional court, the high police agencies. Some of them became businesspeople. So they didn’t disappear.”

Whereas Bulgarian parties struggled to retain control of economic assets, Polish firms established stable ties with political parties that included the exchange of elites. These ties were instrumental for both sides. For example, the former deputy minister of trade and industry, Kazimierz Adamczyk, became the president of EuRoPolgaz, a company that is a critical mediator and beneficiary of trade between Russia’s Gazprom and the Polish natural gas monopoly. Adamczyk also sat on the supervisory board of the Cigna STU insurance company. One of Adamczyk’s former colleagues made a career in the gas business: Roman Czerwinski, the president of PolGaz Telekom, a dependent company of Gazprom, used to be deputy minister of industry. When he was in government, Czerwinski was responsible for the power sector. As minister, he negotiated the contract of the Yamal gas pipeline with Gazprom, while PolGaz Telekom signed contracts on the construction and use of a fiber optic cable, which runs along the pipeline (Polish News Bulletin 2000).

Andrzej Śmietanko, a Polish Peasant Party activist, became minister of agriculture for the PSL government of Waldemar Pawlak and later an advisor to President Kwasniewski. On leaving government, he became the president of Brasco Inc., a company involved in natural gas and part of Gudzowaty’s empire. Śmietanko was a good investment for Gudzowaty because he was a strong opponent of Poland’s largest company and top fuels group, PKN Orlen, when it tried to prevent the passage of a law that would mandate the sale of biofuels in the Polish market. Gudzowaty, on the other hand, had already invested in several biofuel companies and needed Śmietanko’s contacts to push the law through parliament. The latter remains an important figure in the PSL.

These examples suggest that the politicization of property did not end with privatization but instead spread to the emerging private sector. In other words, private property could also be politicized property. All political parties sought to control property in search of advantages during the intense political struggles after 1989. The more intense party competition became, the more deeply this logic took hold.

Whereas the development of a network of loyal party supporters across the state, private, and non-profit sectors took place in every country, these networks took different forms across cases. I explore the mobility of individuals, what sectors they moved between, and, most importantly, the structure of the network of elites that developed as a result of these individual moves.

Poland had an abundance of figures with one foot in the state and one foot beyond, on either the left or the right side of the political spectrum. Elite state officials also experienced a high degree of job mobility during their careers. This supports the argument, made throughout this book, that Poland represents a key variety of post-socialist capitalism that is structured around dense ties in the partisan division of the economy.

Romania instead was a dominant-party regime for much of the first decade, and was dominated by state elites who emerged from a single national unity coalition after the violent and still murky revolution. Overall, Romania has been marked by very low mobility, much of it occasioned by the entrance of the first opposition government in 1996 and its exit in 2000, when many bureaucrats who had served from 1990 to 1996 returned to their state positions. This low mobility was concentrated within the state and was also apparent in the movement of some state officials to the parliament.

Bulgaria experienced the highest degree of mobility, with a high frequency of placements. The range of movement was limited, however, as it was concentrated in moves between private business and the key state ministries that regulate finance and the economy, industrial policy, internal security, and matters related to defense, including highly profitable firms producing arms for export. Such trajectories reflect the ability of business to dominate the state, but, because Bulgarian elites were concentrated in firms and these ministries, the range of career paths was limited and the overall effect was that the Bulgarian network was much less broad than the Polish network.

Networks of individuals

What is the role of persons and personnel networks in the exercise of state power? Do dense networks linking the state to the public sphere enhance state power or impede the exercise of government? By developing the concept of “state embeddedness,” Evans and others have argued that such networks can, under certain circumstances, enhance the state’s ability to make and implement policy by improving information flows and coordination (Gerlach Reference Gerlach1992; Evans Reference Evans1995; Kang Reference Kang2002). On the other hand, some have argued that networks constrain the state’s ability to build institutions and develop autonomy from powerful interests (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1983; Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva1998; Ganev Reference Ganev2007), although these arguments do not explicitly discuss the structure of networks.

As sets of ties that link two or more organizations in a structure that is not just hierarchical, networks connect actors in public administration to other actors in the same ministry or agency, other levels of government, other ministries, and outside the state to private and non-profit actors. Networks can be used to mobilize actors, acquire and share information, generate support, and move a set of actors toward an objective or goal (O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8). Networks related to public administration link actors through three basic kinds of ties – authority, common interest, and exchange (O’Toole and Montjoy Reference O’Toole and Montjoy1984, cited by O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8) – and act as both capacity enhancers and constraints on action by raising the number of potential veto points (Simon Reference Simon1964, cited by O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8). Thus, it is important to distinguish between different types of network structures in order to determine what a particular network can do best. Above all, narrow networks perform different functions from the ones that broad networks do (Scholz, Berardo, and Kile Reference Scholz, Berardo and Kile2008). The former assist in the generation of credible commitments that support cooperation among a small set of actors, while the latter reduce search costs when these pose the greatest obstacle to collaboration. Thus, broad networks between public administration and non-state actors can assist with the conduct of policy by allowing affected groups to communicate concerns to policy makers, receive information about upcoming policy shifts, and generate coalitions of support or opposition by bringing together distant actors around credible commitments to collective action. Narrow networks do not perform these functions (O’Toole and Montjoy Reference O’Toole and Montjoy1984; O’Toole Reference O’Toole1997; Lazer and Friedman Reference Lazer and Friedman2007; Feiock and Scholz Reference Feiock and Scholz2009).

This view is in line with the argument made in this book, with the difference that I consider cases in which the institutional context is incomplete. In the absence of strong institutional constraints, networks matter even more in shaping and determining the types of policies that are chosen. Broad networks reduce search costs, spread information, and mobilize cooperation. The constraint-raising quality identified by Simon (Reference Simon1964) is what leads broad networks to support collective action, as large sets of actors are able to veto narrowly distributive outcomes. This is the dynamic at work in Poland. Narrow networks can support cooperation among small sets of actors and favor narrowly distributive outcomes; this describes the situation in both Bulgaria and Romania. Building on previous chapters, however, the argument developed in the coming pages is that the presence of broader networks is not of itself sufficient to determine whether powerful societal interests collaborate to support the process of institutional development or to subvert it. Instead, network features must be examined together with uncertainty in order to determine how the path of institutional development unfolds.

This chapter considers the uncertainty of career paths that derive from political dynamics, and therefore it focuses on the extent to which job changes coincide with elections. The meaning of a job change is very different if one changes jobs for a better position by choice or if that change is involuntary, prompted by a political dismissal after an election. Frequent election-related job changes suggest the broad politicization of key jobs in a society but also imply that politics serves as an effective check against the prolonged use of powers connected to a particular position by a single individual. The less individuals change jobs over time, the more they are likely to become entrenched power holders. If mass changes occur in the year of or following an election, political ousters likely motivate these changes.

The extent to which an individual moves among jobs affects the density of networks of social ties. If a job holder moves among multiple spheres, he or she will accumulate more ties than someone who moves back and forth between two jobs. I consider historical links to be stored in an individual’s biography as professional capital. Thus, an individual who once worked in a firm and transitioned to a ministry can call on acquaintances made in both positions. Upon moving to a third position, the individual’s built-up professional capital includes networks from both prior contacts. These links are not lost simply because he or she moves on to a new job. Quite to the contrary, such ties can be utilized to build coalitions, and his or her ability to span and connect to individuals in other organizations may be part of what makes him or her attractive as a new hire. Thus, if he or she moves between jobs in different sectors, he or she accumulates historical links to a variety of spheres.

As the data discussed below show, countries vary significantly. Stories about the movement of individuals between the public and private sphere are hardly particular to the post-socialist situation, but they raise interesting questions about the relationship between individual spheres of power and the dynamics of institution building, thus allowing the study of variation in levels and types of systemic influence construction. The pathways of bureaucrats once they leave a particular office are important because they reinforce the popular notion in post-socialist countries that bureaucratic interactions with those who lobby them are part of a longer-term plan to convert political power into other types of power, primarily economic power.1 As noted above, in most eastern European countries the practice of appointing state personnel to firms was a strategy pursued by political organizations to extend political control.2 A great deal has been written in the press about the process and purpose of these exchanges, but little more than anecdotal evidence has been offered to support macro-conclusions about its impact. One often hears, for example, of a bureaucrat being appointed to the board of a firm or an executive being appointed to some governing body in a process that is intended to extend or convert one kind of authority into another (Kublik Reference Kublik2008).

This practice is, of course, advantageous not only to political parties. It is also an attractive strategy to bureaucrats, because it generates “emergency exits” for those who face an uncertain future at each round of elections. For example, in Poland the members of the supervisory boards of the most important firms are also replaced after elections (Grzeszak et al. Reference Grzeszak, Markiewicz, Dziadul, Wilczak, Urbanek, Mojkowski and Pokojska1999; Staniszkis Reference Staniszkis2000). This applies to both public and private firms and is supported by journalistic accounts of individual cases. Similarly, ministerial positions, including lower-level positions, are reshuffled after each election. For example, on June 25, 1994, the leading Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza commented in connection with the then prime minister, “The ease with which Pawlak’s team disposes of the best professionals at every level of the government and ministerial administration prompts amazement and dismay” (Vinton Reference Vinton1994).

These practices are in line with a minimal conception of the state in post-socialist countries that has emerged in the literature. The post-socialist state was initially considered to be an autonomous and strong actor that needed to be dismantled, because it was assumed that the socialist state had been a strong state. More recent studies, in particular Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong’s (Reference Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong2002) direct treatment of the question, have urged a reconsideration of these states as particularly weak, requiring rebuilding to meet new administrative challenges.

Yet rebuilding was unlikely to take place in the conventional fashion: by erecting new institutional structures that were legitimized and that bound actors in rule-following behavior. Even if the situation on the ground could have made this possible, pressure coming from international policy advisors tied the hands of the state and limited the extent to which state structures could take an active role in the construction of markets. As a consequence, alternative structures developed to link political and economic actors. For example, during this period state economic activities were largely controlled or bounded by clientelistic relationships with powerful actors who had the money or means to threaten the state. Political parties with access to decision-making authority were similarly drawn into this web of relations.

Thus, one promising avenue for a reconception of the state focuses on elites (Levi Reference Leff1998; Waldner Reference Waldner1999; Migdal Reference Meyer-Sahling2001; Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong Reference Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong2002), implicitly exploring the notion that the extension of state control and prestige is largely connected to the paths, networks, and initiatives of individuals. This reconception requires a shift toward considering the state as a non-unitary actor – one that operates through disjointed areas of influence that are in the process of consolidation while under pressure from social forces.

In this conception, pathways and relations are strategically deployed so as to maximize the career prospects of the individual and the organization vis-à-vis the state. Such strategic behavior aims to increase individual holdings in one or more of the key currencies in circulation: money, policy influence, and information. These paths form a macro-structural pattern of behavior, which all elites attempt to read and estimate in order to plan their next move. And, with each new move, the value of all members’ network capital grows.

Behind this conception is a particular assumption about the state and the individuals who constitute it. In the weak states considered here, politics penetrates all areas of the state, and individuals are part of this political structure more than they are part of the state agency in which they work. This dynamic can also be attributed to attitudes stemming from before 1989, when all positions were obtained through the ruling communist party. Rather than shedding this trend after transition, there is ample evidence that new political parties, such as the Polish SLD and AWS or the Bulgarian UDF and BSP, adopted it. Hence, it is useful to view the state as constituted by individuals in diffuse political organizations, in the sense that the individuals are not located in one particular place but have fanned out across a variety of social arenas, moving along mutually self-serving paths.

It follows that much can be learned by observing the macro-structural patterns of elite movement. When summed together, different patterns of movement will give rise to very different configurations of networks. In turn, this should lead to different types of states, as a greater or lesser number of individuals control or have access to a network that fulfills functions such as the transmission of information, the facilitation of coalition building, the creation of policy cliques, and an awareness of the interests in different policy arenas. Succinctly, networks facilitate or impede the group mobilization of resources.

By following the development of the networks below, I observe how the state comes to occupy a particular position of relational power. These ties are the “embeddedness” of which Evans and others have written, and which enables the state to make informed policy decisions that have the support of societal actors by taking advantage of the feedback that flows through these ties. The following pages analyze how state power and state consolidation were supported or constrained by the informal organization of networked individuals.

Anticipating the findings, the analysis indicates the importance of two dimensions. First, it highlights the role of elite mobility. I find a striking difference between the breadth of embeddedness in the three cases. The Polish network is much wider than the Bulgarian network, although elites are more mobile in the latter. In Poland, networks spread further and linked social spheres and power brokers more broadly over time. In Romania, network breadth is much lower and elites are much less mobile as a whole. The presence of broad relational contacts between the public and private sectors in Poland challenges the notion that network ties between elites generated many of the pathologies of post-socialist government. The lack of such ties in Romania and Bulgaria – countries known for their poor governance – provides negative cases.

Second, this analysis reveals very different patterns of movement between the state and sectors of the private economy. The closeness of certain areas of the private sector to the state go hand in hand with particular paths of institutional development. The frequent movement of individuals from the private sector into the state in Bulgaria is a central part of the story of state capture that has been told qualitatively elsewhere in the literature (Ganev Reference Ganev2001; Ganev Reference Ganev2007). This pattern is in stark contrast to the dominant movement in Poland: of party functionaries from the parliament to key ministries and sometimes private business. Romania represents a third variant, in which elites circulate from high positions within the state outward, although with far less frequency and more limited breadth.

How elite networks differ across countries

The argument in this chapter is based on a relational approach to the state. In political science, states generally continue to be conceptualized as black boxes. In some empirical studies, scholars explore the actual interactions of state bureaucrats with societal actors (Evans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol Reference Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Evans Reference Evans1995). Even in studies of the post-socialist countries, however, in which much of the political science literature has been focused on how ties between state bureaucrats and societal actors are responsible for corruption, there is a tendency to discuss what states “do” (Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva1998). Rarely, as a result, is the link made between the role that individual actors play and the enabling or constraining effects of individual relational ties.

One aim of this study is to develop a less unitary vision of the state and contribute with empirical substance to the conception of the state as an arena (Mann Reference Mann1984). The analysis thus uncovers how the networks of individual state bureaucrats contribute to the development of state power. To this end, it traces the development of these networks, which are difficult to observe, from a perspective that is available to researchers. As in the example of the Baron Rothschild discussed in Chapter 1, when we move to a temporal conception of networks, network approaches are able to capture both structure and agency. Thus, by observing the same network over time, we can observe the effect that structure has on individual choice within a network.

Summarizing the data presented below, Table 5.1 shows the sharp differences in personnel network development across countries. In the Polish case, networks were conditioned by high uncertainty in the form of frequent changes of the party in power, which led to the regular reshuffling of network ties because individuals were removed from their jobs by an external political shock (this is labeled in the table as the “Impact of elections”). Individuals also tended to move between sectors with a wider range than in the other two countries. As a result, the average individual occupied more positions, and the resulting career network linked many more individuals (this is labeled in the table as “Career heterogeneity”).

Table 5.1 Comparison of cases

In Bulgaria, ties were much more homogeneous but slightly more conditioned by political change over time than in Poland. Occupants of elite bureaucratic positions were significantly affected by electoral shocks and forced to switch jobs in post-election years. They also were highly mobile in non-election years. These moves tended to be within the same sector, however. Many simply returned to their pre-election positions once their own political party returned to power. As a result, Bulgarian personnel networks did not develop the same type of breadth as in Poland, and individual careers did not develop to link diverse organizations and sectors.

As a result of these network structures, Bulgaria became the victim of strong societal interests that had close ties to entrenched bureaucrats in key ministries, which is, in fact, a feature often identified to explain the laggardly performance of Bulgaria in building functional market institutions (Ganev Reference Ganev2007). The reasoning that is commonly implied – that networks link the early winners of reform, who colonize the state – is incorrect, however (Hellman Reference Hellman1998; Ganev Reference Ganev2001; Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2003). As previous chapters have shown in other contexts, what differentiates Poland from Bulgaria is not the presence of networks but their structure.

In all three countries, career networks were affected by elections. Electoral turnover is high in Poland and Bulgaria and weak in Romania, however. Thus, if a single quality marks the careers of Romanian state personnel, it is stability. Individuals in Romania change jobs less frequently, and these changes are not affected by electoral outcomes nearly to the extent that is true in the other cases.

Data

The data used here were collected in Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania. I first collected a list of ministers, deputies, secretaries, and undersecretaries in the Ministries of Finance, Economy, Industry and Trade, Interior, and Defense for all governments during the period 1993 to 2003. Subsequently, a database that included the career paths and declared political affiliations of these individuals for the entire period was compiled. For each person, his or her primary or full-time occupation was coded. The Polish data set covers the complete careers of 105 persons from 1993 to 2003, the Bulgarian dataset covers 106 individuals from 1992 to 2003, and the Romanian dataset covers 149 people from 1990 to 2005. Each cell was recoded into one of eighteen possible job categories culled from the whole range of jobs occupied by members of the data set. These categories are: “Ministry of Finance,” “Ministry of Economy,” “Ministry of Industry and Trade,” “Ministry of Interior,” “Ministry of Defense,” “Ministry of Foreign Trade,” “Other top government positions,” “Business organizations,” “International organization/EU,” “Labor unions,” “State firms,” “Private firms,” “NGOs” (non-governmental organizations), “Diplomatic corps,” “Senior military and police officials,” “Parliament,” “Political party,” and “Academic/journalist.” These were then recoded according to Table 5.2 into a reduced schema that captures the various sectors of society represented in the data set.

Table 5.2 Coding of data3

This database details joint membership in groups, parallels and divergences in the paths of individuals, and the potential “reach” that develops as the network becomes more connected. The codes represent the transformations undertaken by the governing elite as they moved between the state bureaucracy, the business sector (state and private), pressure groups in the NGO sector, international organizations, and the media.

Comparative network development

What macro-patterns can be identified in the data over time, and what differences emerge from a comparison of these three cases? The exploration of the data set described above highlights two dimensions in the configuration of elite career paths: (1) the impact of elections (which captures uncertainty by looking at the degree of mobility – i.e. the frequency of change in jobs); and (2) the range of career destinations (which captures network breadth). Pulling together the degree of mobility and destination range, career paths are a way to materially capture the different relationships between state and economy generated by the interaction of political uncertainty and network breadth.

The impact of elections

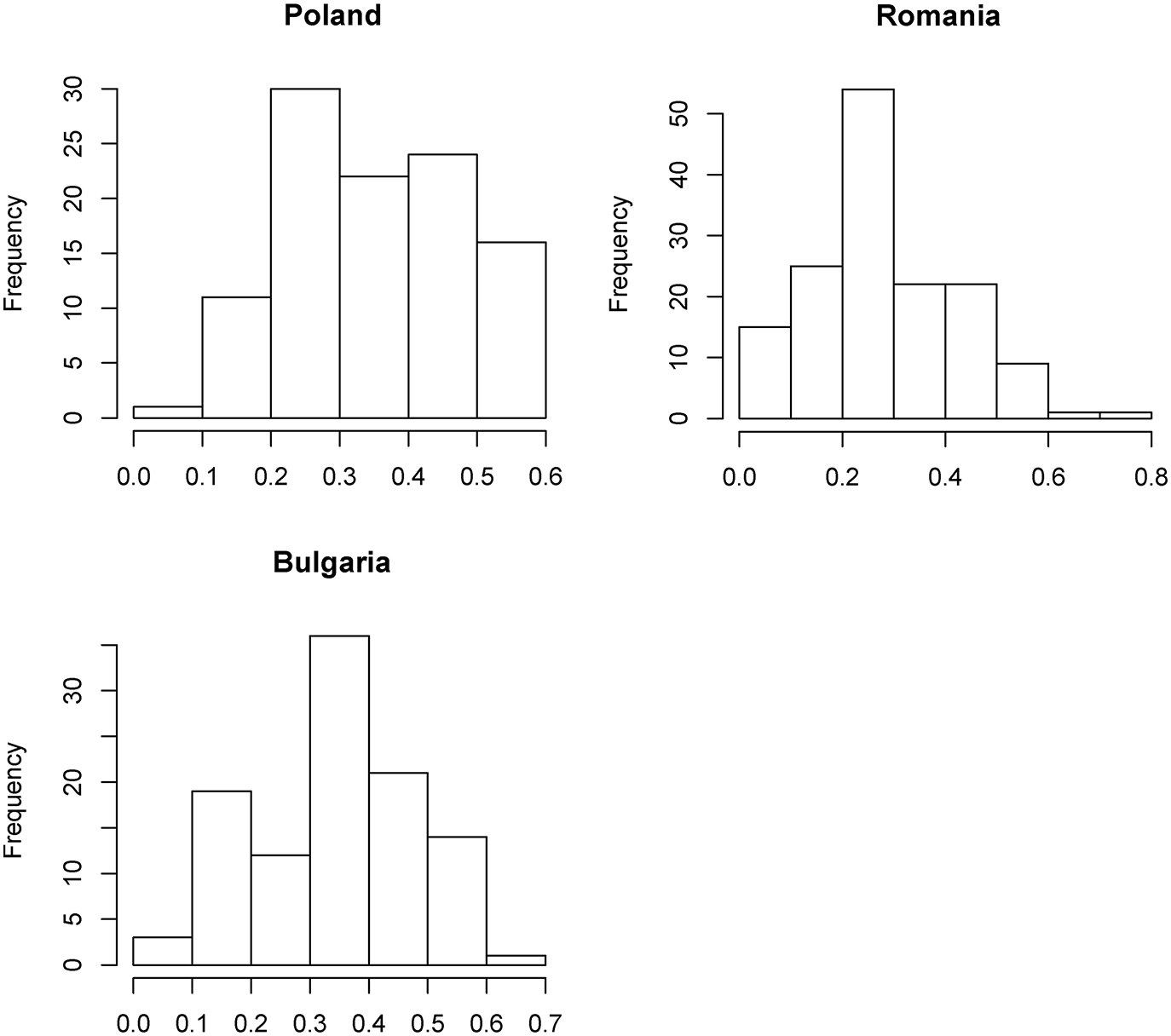

The stability of the network over time captures the extent to which individuals sit in their appointed positions. It expresses the amount of mobility or “turbulence” in the macro-social system as people shift across positions – the extent to which the broad system is disrupted. Some countries are generally more turbulent than others because their social systems – in this case the system of professional appointments – are subject to more frequent shifts. There are also some events that are turbulence-inducing. Elections are particularly significant events of this type. In all three cases in this book, elections bring about broad changes in the staffing of high-status jobs, indicating that high-level positions are political. The degree of such shifts varies, however. The job of an individual at any given time can be considered a state, and a career as a sequence of states. Figure 5.1 captures the average number of transitions across states in non-election years and post-election years.

Figure 5.1 Yearly average of elites changing jobs

Note: Average percentage of job turnovers per year.

The Romanian career network experiences the lowest number of state transitions per year in the year following an election. Individuals there are also highly unlikely to change jobs in any given year, although their chances of doing so rise in post-election years – as they do in other countries. This result is driven by the changes that took place after the 1996 victory of a broad coalition of parties that first interrupted the Social Democrats’ hold on power after 1989. In other periods, the Romanian network experienced much less change. In any given non-election year an average of only 15 percent of individuals in this data set shifted career state.

By contrast, the Bulgarian network was highly turbulent; in any given year nearly a quarter of all individuals shifted jobs. In post-election years more than 35 percent were affected by job changes. Poland is much like Bulgaria: a highly fluid and deeply politicized society in which elite positions in both the public and the private sector are awarded according to political affiliation.

Considering the distribution of different levels of state transition in a population also reveals sharp differences between the cases. One useful measure is sequence entropy.4 If each individual career is considered a sequence of states, then sequence entropy can be interpreted as the “uncertainty” of predicting the states in a given sequence. Sequence entropy is measured on a normalized scale of 0 to 1. If all states in the sequence are the same over time, the entropy is equal to 0. If every state is different, the value is 1. Values reported here are normalized and comparable across country data sets. The distribution of sequence entropies is shown in Figure 5.2, which presents frequency distributions for levels of sequence entropy in each country.

Figure 5.2 Sequence entropy by country

The variance is striking. Romania has a stable and static social system and is different from the other two cases, which experience a much higher degree of individual mobility. Poland and Bulgaria also differ in the extent to which individuals move, however. In Poland, the general population of elites shifts jobs regularly, with about 60 percent of the sample being highly mobile and transitioning through many jobs over the course of a career. By contrast, Bulgaria’s elite tends not to transition through quite as many jobs, and a concentrated group of individuals is much more mobile than the rest of the population, as can be seen in the more bell-shaped distribution of frequencies.

The frequency of shifts reflects the extent to which individuals become entrenched office holders. Whereas, in Poland, no one can afford to be too comfortable in a given post, and this is true across the population in the public and private sectors alike, in Bulgaria only a subset of individuals is affected by the political forces that lead to frequent state transitions. The vast majority in Romania, instead, experience very few state changes. The distribution does indicate that some of those in a political office shift position, but they move on to a new job in which they are likely to become entrenched power holders. The great majority have quite stable careers.

The effect of network breadth

The previous dimension captures the extent to which political shocks determine mobility. The analysis confirms that Romania is a country with little mobility, in response to a static political environment, while the elite in Poland is subject to frequent moves. Bulgaria is similar to Poland, although the elite is slightly less mobile.

Another important component for the argument is the extent to which accumulated contacts in any given country give an individual access to a heterogeneous network. In other words, the breadth of networks linking the state and the economy determines the range of opportunities for career shifts. One can imagine that, at every transition, individuals either fan out across the economy to take up positions in other sectors or perhaps return to an organization in which they previously held a job. The first is a more open system, in which individuals enjoy broad access to different types of organization. This produces individuals with diverse contacts, and organizationally benefits an elite that is jointly seeking to solve search and coordination problems. The second is much less open. Individuals move less, and, when they do move, they are less likely to change organizations or sectors. Instead, they seek or are placed into entrenched positions of power. As an elite system, this second variant is well suited to small groups seeking to address problems of collaboration – behavior that may even be called collusion.

Thus, the analysis now turns to the ties that were formed by individuals changing jobs. A single tie between two organizations means that an individual worked in both and thus provides a human link between them. For example, if a single Romanian bureaucrat worked in the Ministry of Finance and then moved to work in the private business sector, he or she provides a single human pathway between two organizations and two spheres of the social world: the state and the private economy.

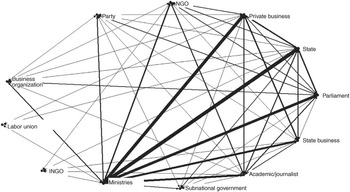

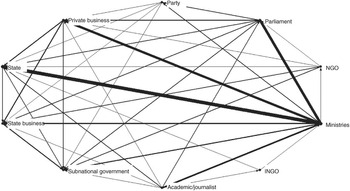

The graphics in Figures 5.3 to 5.5 were obtained by comparing the same eleven-year period for each country (1993–2003). The networks are presented in Figures 5.3 for Bulgaria, 5.4 for Poland, and 5.5 for Romania. These images represent the connectedness of the network at the end of the whole period under study. Although the networks pictured here actually represent a three-dimensional web that includes time, the two-dimensional image shows the state of the network at the end of 2003 and includes all of the relations that were formed from the first year of observation, 1993.

Figure 5.3 Bulgarian network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003 Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.

Figure 5.4 Polish network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003. Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.

Figure 5.5 Romanian network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003. Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.