1. Introduction

Several scientific communities (e.g., One Health, Ecopsychology) and international health organizations (e.g., World Organization of Family DoctorsFootnote 1 [WONCA], Clinicians for Planetary HealthFootnote 2 , Climate Psychology AllianceFootnote 3 , WHO (WHO, 2021) are calling on the healthcare sector to rethink their relationship with nature. They advocate a vision of health in which the interrelationship between biological, human, social and environmental determinants is integrated (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Davies and Pelikan2006; WONCA, 2017; Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Logan, Bristow, Rozzi, Moodie, Redvers, Haahtela, Warber, Poland, Hancock and Berman2022). Furthermore, WONCA (2017) suggests that since healthcare professionals (HCP) are seen as trusted and committed individuals, they can become role models through integrating an integrative health approach. For example, HCP can inspire other colleagues, patients or clients how the integrated, holistic and transdisciplinary One Health (OH) approach can be integrated in private and professional practice and how it can benefit the reciprocal human-nature health relationship. In addition, the IPCC 2022 Mitigation of Climate Change report suggests the need to engage in an inner transition process, such as through raising awareness, changing beliefs, values and agency regarding the human-nature relationship (Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Logan, Bristow, Rozzi, Moodie, Redvers, Haahtela, Warber, Poland, Hancock and Berman2022).

A growing number of studies demonstrate the salutogenic effects of contact with nature on various dimensions of health in the general population (Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Simons, Losito, Fiorito, Miles and Zelson1991; Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1995; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Frantz, Bruehlman-Senecal and Dolliver2009; Barton and Pretty, Reference Barton and Pretty2010; Hartig et al., Reference Hartig, van den Berg, Hagerhall, Tomalak, Bauer, Hansmann, Ojala, Syngollitou, Carrus, van Herzele, Bell, Podesta and Waaseth2011; Nisbet and Zelenski, Reference Nisbet and Zelenski2013; Lumber et al., Reference Lumber, Richardson and Sheffield2017; Martin et al., Reference Martin, White, Hunt, Richardson, Pahl and Burt2020). Additionally, studies have shown how a more relational attitude towards nature (often referred to as nature connectedness or reciprocal) can help in achieving both better self-care (SC) and higher well-being, as well as in improving care of the natural environment (Buzzell & Chalquist, Reference Buzzell and Chalquist2009; Stigsdotter et al., Reference Stigsdotter, Palsdottir, Burls, Chermaz, Ferrini and Grahn2011; Seymour, Reference Seymour2016), and adopting a sustainable lifestyle (Zylstra et al., Reference Zylstra, Knight, Esler and Le Grange2014; Restall and Conrad, Reference Restall and Conrad2015; Zelenski et al., Reference Zelenski, Dopko and Capaldi2015; Mackay and Schmitt, Reference Mackay and Schmitt2019). However, the implementation of these scientific findings into healthcare practice is still rare (Frumkin et al., Reference Frumkin, Bratman, Breslow, Cochran, Kahn, Lawler, Levin, Tandon, Varanasi, Wolf and Wood2017; Summers and Vivian, Reference Summers and Vivian2018; Lauwers et al., Reference Lauwers, Bastiaens, Remmen and Keune2020).

Furthermore, HCP themselves increasingly suffer from stress, burnout, and depression (Dyrbye et al., Reference Dyrbye, Shanafelt, Sinsky, Cipriano, Bhatt, Ommaya, West and Meyers2017; Lemaire and Wallace , Reference Lemaire and Wallace2017; Vandenbroeck et al., Reference Vandenbroeck, Van Gerven, De Witte, Vanhaecht and Godderis2017; Jha et al., Reference Jha, Iliff, Chaoui, Defossez, Bombaugh and Miller2019), often accompanied by lack of efficient SC due to several factors. For example, a study by the British Medical Association has highlighted the problem of physicians being exposed to high levels of stress and risk of burnout (BMA, 2019). More recently, during the Covid-19 pandemic, mental health problems among HCP soared (Vanhaecht et al., Reference Vanhaecht, Seys, Bruyneel, Cox, Kaesemans, Cloet, Van Den Broeck, Cools, De Witte, Lowet, Hellings, Bilsen, Lemmens and Claes2020; Vizheh et al., Reference Vizheh, Qorbani, Arzaghi, Muhidin, Javanmard and Esmaeili2020; Chirico et al., Reference Chirico, Nucera and Magnavita2021; Søvold et al., Reference Søvold, Naslund, Kousoulis, Saxena, Qoronfleh, Grobler and Münter2021).

To date, previous studies have mainly focused on the concept of SC (Bressi and Vaden, Reference Bressi and Vaden2017; Butler et al., Reference Butler, Mercer, McClain-Meeder, Horne and Dudley2019; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Connelly, Pérez and Calero2021), its conditions and barriers (Dattilio, Reference Dattilio2015; Butler et al., Reference Butler, Mercer, McClain-Meeder, Horne and Dudley2019; Laposha and Smallfield, Reference Laposha and Smallfield2020), and the effectivity of SC strategies (e.g., mindfulness, exercise, healthy nutrition) in maintaining physical, mental and social health. However, to our knowledge, limited attention has been paid to how HCP relate to their SC, their relationship with nature and their professional practice. Gaining more knowledge in this area could provide guidelines that can be incorporated into the professional education and development of HCP and help them to become role models.

Therefore, this Belgium-based study investigates how primary HCP integrate SC and nature into their private and professional practice. Specifically, we examine how Belgian HCP relate to their SC, their relationship with nature and its implementation into their professional practice.

A high incidence of burnout and strained mental well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic are also evident among Belgian HCP (Vanhaecht et al., Reference Vanhaecht, Seys, Bruyneel, Cox, Kaesemans, Cloet, Van Den Broeck, Cools, De Witte, Lowet, Hellings, Bilsen, Lemmens and Claes2020; Deman et al., Reference Deman, Seys, Cools, De witte, Claes, Van den Broeck, De Paepe, Lowet and Vanhaecht2022). Yet, interestingly, in recent years there has been growing interest in integrating a OH approach into healthcare (Keune et al., Reference Keune, Flandroy, Thys, De Regge, Mori, Antoine-Moussiaux, Vanhove, Rebolledo, Van Gucht, Deblauwe, Hiemstra, Häsler, Binot, Savic, Ruegg, De Vries, Garnier and van den Berg2017; Rüegg et al., Reference Rüegg, Häsler and Zinsstag2018).

2. Aim of the study

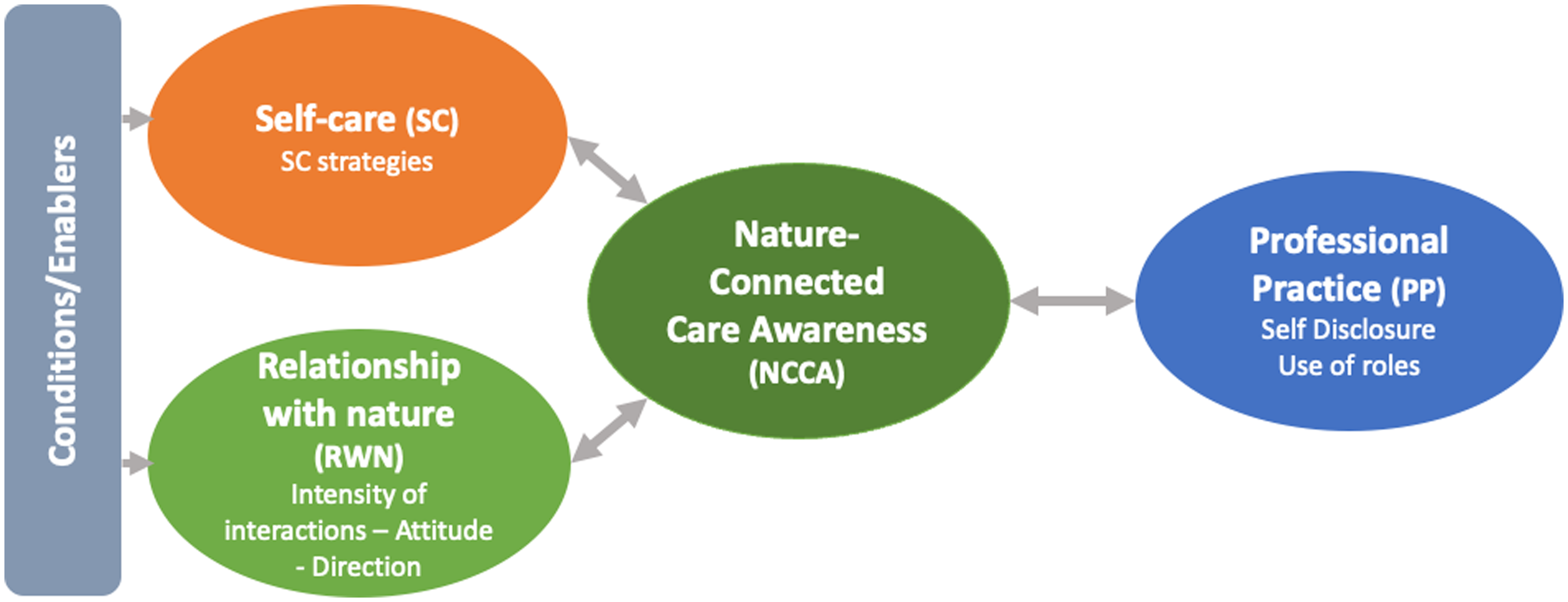

With this study we aim to answer the following research question (Figure 1):

Figure 1. The research topics and its interrelationships.

How do primary health care professionals (HCP) in Belgium relate to their self-care (SC), their relationship with nature (RWN) and its implementation into their professional practice (PP), and what are their interrelationships?

3. Methods

Due to the novelty of the topic, an exploratory qualitative research design was chosen. Hereby we investigated the interrelationship between (1) SC and RWN, (2) SC and PP, (3) RWN and PP, and (4) the overall pattern which might mediate these interrelationships (see Figure 1). We examined each of the topics before turning to the possible interrelationships.

Participants were primary HCP in Belgium. To facilitate the recruitment during this Covid-19 period, we combined purposive sampling with snowballing recruiting techniques (Morgan, Reference Morgan2008). The main selection criterion was whether the HCP already integrated their RWN into their PP. AS initiated two personal connections differing on this selection criterion. Next, to surpass possible bias and lack of diversity, and to differentiate in the recruitment, each participant was asked to suggest two persons differing on this selection criterion. Recruitment continued until we experienced saturation during analyses.

After written informed consent, semi-structured interviews entitled ‘Self-care of primary healthcare professionals’ were conducted, based on a topic list created by AS (Supplementary Material). Data collection took place between March 2020 and March 2021. Due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the interviews were held and recorded using Zoom. In each interview, AS first referred to their previous email conversation. Next, to make participants feel at ease, AS posed questions about themselves and their work situation. To avoid social desirability bias, the aspect of RWN was not introduced at the beginning of the interview. Moving back and forth between SC, RWN and PP, AS initiated a topic which was not raised spontaneously, ensuring all were explored.

Data analysis was inspired by thematic analysis (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2009). To derive themes, a six-step framework (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2012) was used (Figure 2). AS first became familiar with the data by personally transcribing the interviews. Next, the interviews were imported into NVivo and anonymized. AS then analyzed them in three steps. Firstly, inductive analysis was performed by coding the transcripts line by line (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2009). A constant comparative method during analysis of each interview was used (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014). Secondly, deductive analysis was performed, followed by the third step, namely abductive analysis (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2009), in which new patterns may emerge. After four interviews, AS held a consultation with two other researchers (KVDB and an external researcher), after which the topic list was adapted where necessary. The same approach was applied with the following interviews until saturation was reached. Thirdly, AS searched for themes by merging patterns. Then, themes were merged under the topics SC, RWN and PP in function of the research questions, after which the themes were named. Finally, AS wrote the research report.

Figure 2. Data analysis based on the six-step framework (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2012).

A two-step member-checking of the findings was conducted by email. In the first step, participants were given the option to add information to the transcript they received. In the second step, each participant received a summary of the results (see Supplementary Material). Questions were asked about the topics with their respective themes, and answers were offered as multiple-choice, so they could check which patterns they recognized. We also asked how participants were affected by the interview and the member-checking, with the latter being integrated into the final analyses. In addition, an external validity check was performed by giving several presentations to HCP and medical students about the preliminary findings. Cross-referencing the findings in the literature was also executed and new literature sources were searched to further clarify the findings.

Ethical approval for this study had been given by the Ethical Committee Universal Hospital Antwerp with the number EC/PM/AL/2020.060.

4. Findings

4.1. Participants

A total of 19 HCP were contacted, of which 16 participated (Table 1). As we experienced saturation in the analyses, recruitment was stopped at this stage. In the first step of the member-checking, only two persons asked for a small refinement in the transcript. In total,14 of the 16 participants took part in the second member-checking step.

Table 1. Distribution of participants

This study included nine general practitioners, six psychologists and one special education generalist providing psychological counseling. Three GPs combined their practice with teaching at university. Eight HCP were identified as HCP already integrating the relationship with nature into their PP. The codes, used for anonymization, do not reflect the order of interviewing.

4.2. How do primary healthcare professionals in Belgium relate to the topics of self-care, their relationship to nature and its implementation into professional practice, and what are their interrelationships?

Before discussing the interrelationships, the topics of SC, the RWN and its implementation into PP will be addressed individually.

4.2.1. Self-care

Exploring the topic of SC led us to identify three key aspects. First, to stay close to the participants’ language and understanding of SC, we developed a general definition based on their input. Second, we determined several SC strategies. Third, we introduced the term ‘self-care paradox’ to refer to SC being hampered by ineffective personal strategies that impair the goal of SC (e.g., relaxation, recovery).

We invited the participants to describe in their own words what SC means to them and how they experienced it. Summarizing their answers, we defined SC as:

Self-care is a developmental issue in which one can grow, supported by creating time and space for oneself, reflecting and taking care of one’s basic needs, physical, mental and social health, preserving several types of balance and a certain stability in life, and activities that bring inner peace, rest and relaxation.

When asked how they take care of themselves, most participants seemed to enjoy multiple SC strategies, of which taking time and creating space for yourself was most common. As mentioned by one participant it means: 'taking time for yourself and for your needs, to relax, or shift your thoughts or step out of the rush of everyday life’ (GP8). Next, taking care of physical and mental health were often mentioned together. Examples were a healthy diet and physical activity (yoga, walking, running, fitness, going into nature, mindfulness) or seeing a counselor or psychologist when needed. In contrast, maintaining social relationships seemed to be of a different order. Some participants mentioned how caring for one’s partner, family relationship, or friendships could support SC: ‘Self-care is also taking time for the relationship with your partner’. (PSY6). One explanation could be that social relationships are more important to some people than to others: ‘I am also a family man. I have found that this is important to me. And that I often find time to go to my grandma or my parents’. (GP2). The most challenging strategy was ‘maintaining balance’ between: workload and resilience, work and relaxation, give and take, caring for others and caring for oneself, and finally, feeling good at work and at home. SC has also been understood to focus on what energizes and the important things in life: ‘Managing yourself more so that you can be stable in life, investing your time in the things that you find important in life, and investing little time in the things that you don’t find important’ (PSY2). Other participants mentioned doing enjoyable activities, and ‘recharging your battery’: ‘It’s about your balance between real load and load capacity and that you know what gives you energy. That means you ensure enough breaks during a busy day, so that you can charge your battery for a while’. (PSY5). Lastly, SC has also been viewed as boundary setting; the ability to feel and set boundaries for oneself, by listening to one’s needs: ‘And most importantly, I think, also listen to yourself, set your boundaries, make sure that there is occasionally time for self-care’ (GP8). In addition, it is about encouraging self-control to stop whenever your boundary is crossed: ‘Listening to your needs, and recognizing your boundaries in time to not cross them’. (PSY1).

Lack of energy, mental and physical space, and time have been cited as barriers to SC. An attempt is made to change something about the situation, but in retrospect it does not seem to have the desired effect: ‘But then I lack the ability to do that. There are always more important things: computer work, patients, family, shopping and the like, and that happens often, far too often’. (GP1). As a result, the person tends to feel more depressed rather than energetic. In other words, in such a case the individual lacks the self-control to use effective SC strategies. Consequently, self-control does not seem to change the situation at a point where SC is really needed. In this study we will refer to this phenomenon as the ‘ self-care paradox’ .

4.2.2 Relationship with nature

In the interviews we used the word ‘nature’, by which we mean ‘any element of the biophysical system, which includes flora, fauna, and geological landforms occurring across a range of scales and degrees of human presence. “Nature” can therefore be understood as the biophysical environment as it exists without humans, bearing in mind that “nature” is largely a social-cultural construction and its conceptualization varies between different contexts and is inevitably influenced by such contexts’ (Zylstra et al., Reference Zylstra, Knight, Esler and Le Grange2014). All participants talked about nature in this sense. In their descriptions, multiple types of landscapes, such as forests, parks, mountains, the garden, the sea, and coastal areas were mentioned. Natural elements, such as birds, plants, grass, flowers and trees were also mentioned.

The exploration about the participants’ RWN brought five main findings to light. First, visits to nature seemed to occur mainly during private time, that is, on weekends and holidays. On workdays, experiencing nature seemed to be more fragmented and not integrated into everyday life: ‘When we travel, that’s when we go out into nature, I can enjoy that immensely. But I don’t do that enough in everyday life’. (PSY1). Second, several qualities and intensities of interactions with nature were mentioned. For example, nature often seems to be perceived primarily as a context in which we can be active, relax, or experience wonder: ‘Walking and hiking I do a lot. It does help me to be outside, to see nature, which is always good to relax’. (PSY5). Although further probing was necessary, deeper emotional experiences towards nature were mentioned. Some even spoke of spiritual and existential experiences: ‘I can really enjoy watching seedlings appear. You have beauty, you are so close to life, you see that growing, that tells us so much about life and that is so translatable to who we are as human beings’. (PSY4). An overview of the different mentioned kinds of interaction with nature, ordered in function of qualification and level of intensity, are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of the intensities and qualities of interaction with nature

Third, given the findings above, the overall RWN can be explained along a continuum (Figure 3). First, there is a level of intensity, namely going from nature contact (shallow) to nature connectedness (deep) (Ives et al., Reference Ives, Giusti, Fischer, Abson, Klaniecki, Dorninger, Laudan, Barthel, Abernethy, Martín-López, Raymond, Kendal and von Wehrden2017; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Dobson, Abson, Lumber, Hunt, Young and Moorhouse2020). Second, a person’s attitude towards nature can range from instrumental to relational (Jax et al., Reference Jax, Calestani, Chan, Eser, Keune, Muraca, O’Brien, Potthast, Voget-Kleschin and Wittmer2018). Finally, the level of direction can range from a unidirectional to a reciprocal relationship, in which the interactions are not only beneficial for humans, but also for nature (e.g., ‘giving back to nature’).

Figure 3. Continuum of the relationship with nature explained by its level of intensity, attitude and direction.

Fourth, as with the SC topic, several conditions for experiencing nature were mentioned. Some participants mentioned the need to be alone: ‘Then I like to be alone to empty it all out a bit. Here behind us the forest, the fields. Quiet, away from cars and stuff as fast as possible. That’s what I do, peace, just silence’. (GP2). For others it is important to be in the company of like-minded people: ‘Unless I feel that’s someone who can be fully present in nature… And then I don’t have to be alone, it’s about the presence of someone who dares to admit these same things’. (GP1). Admiring or wondering at nature requires a certain openness or maturity: ‘People must be ready for that (opening up to nature), and that’s not always so easy. You must go for a walk and be able to notice that there are beautiful flowers’. (GP5). Some participants mentioned that to experience a deep connection with nature, it is necessary to be physically present in nature: ‘It’s only when you are really standing there that you’re experiencing that’. (GP4). Finally, feeling safe was also a condition, understood here as the feeling that others would not find it strange if you have a certain experience in nature or, for example, leaning against a tree: ‘But when it’s really about self-care, the healing potential, I think it’s best if I go alone. I might need a high degree of security for opening up. When I go for a walk here in the woods in the neighborhood, it’s always crowded, and maybe that doesn’t give me enough that safe feeling’. (GP1).

Finally, several of nature’s health benefits were mentioned, although most participants did not connect it straightly with SC. A feeling of happiness was a shared feeling by most participants: ‘I get a lot of satisfaction when I’m in nature, you come out of that very happy. It’s a kind of endorphin cure that I get, probably also because of working out, and because failure is actually not possible there’. (PSY3). Another participant talked about the healing power of nature, for example during recovering from illness: ‘In the sense of, time after time, when I go into nature, I experience how it heals. (…) In 2012, I had a burnout, and being in nature really was my salvation’. (GP1). Also mentioned was the healing power in the context of grief: ‘I had just graduated, my father died of cancer and that was a shock to me. I remember that I went many times to the sea. I got comforted and tranquil by that mass of water and the tides’. (PSY4). Going into nature might also lead to a feeling of inner peace: ‘Nature is really a place where I look for peace and quietness. That’s a lot more soothing. Looking at things in wonder, that’s where I can best clear my mind’. (GP8). Finally, it helps to relativize or see things from another perspective: ‘Yes, vacation, having a break, it’s not all that important when you’re sitting here [in nature]. It helps you to put things in perspective’. (GP5).

4.2.3. Implementation into professional practice

Implementation of self-care into professional practice

The implementation of SC concerns two levels. The first concerns the degree of SC while working, the second concerns addressing the topic of SC during the consultation.

When AS asked ‘how do you perform SC in your PP?’, AS received answers that concerned their patients or clients rather than themselves. This may be due to a linguistic misunderstanding or another underlying pattern. Therefore, AS asked the question more explicitly. Those who seemed more aware of the need for SC while at work referred to the SC strategies they had learned during their professional education, such as time management, organizational strategies (e.g., having a well-functioning secretary or outsourcing of the telephone system) and self-reflection.

During consultations most HCP address the topic of SC, each using their own method. Generally, they will first ask their patients or clients how the person performs SC. Additionally, they do self-disclosure about their own SC strategies, based on what has proven to be successful for them: ‘I always tell the patient that this is what works for me; I also sought and found that out through trial and error, and that that’s exactly the process they’re in now’. (PSY4). Next, it appears that the HCP use distinctive roles to address the topic of SC during their consultations (Table 3). Inspired by the Social Role Theory in social sciences (Biddle, Reference Biddle2013), we define ‘role’ in this study as ‘a coherent set of patterns of behavior or use of certain communication skills, expected of the HCP when addressing a specific topic during the consultation’. For example, the topic of SC might be discussed using an educational role in which the patient or client is taught why it is important to take care of oneself: ‘I teach them, together, to see what they should invest more in, and what they should invest less in’. (PSY2). Another example is the role of awakening, in which the patient or client may be confronted with his patterns or other perspectives: ‘If that’s really important for you, medication alone is not going to solve it, you also need to make an effort’. (GP2).

Table 3. Use of roles when addressing the topic of self-care during the consultation

Interestingly, more roles were crossed in the member-checking than were mentioned during the interview. From a scientific and methodological point of view, it may be that the roles offered stimulated a certain amount of wishful thinking. On the other hand, one might assume that reflecting on personal themes using multiple methods (e.g., interview, questionnaire, sharing best practices), could lead to raising the participants’ self-awareness.

Implementation of the relationship with nature into professional practice

While the participants show some richness in their RWN, we found that it is rarely implemented into their PP with the same depth. Also, it is not often offered as a complementary healthcare option. Nevertheless, after probing, some examples of the inclusion of the RWN in PP were mentioned and confirmed in the member-check, which we discuss below.

Some participants introduce plants, pictures of nature, and nature magazines in their office. Using nature stories or metaphors to inspire their patients or clients was also an example. This helps to clarify something in a different way. Also, one participant said he uses them when it is not possible to go out into nature: ‘I work a lot with hypnotherapy. A very rewarding source for me are nature stories. When you are in a trance, you can experience that. So, in that sense the client automatically gets the experience of nature’. (PSY2). Some participants prescribe non-formalized nature prescriptions. For example, suggesting the patient or client goes for a walk, as green exercise (Barton & Pretty, Reference Barton and Pretty2010), is most common, while not always indicating this should be in nature. However, three participants explicitly stated their preference that the walk should be in nature: ‘I say that hundreds of times they should go more into nature, into the woods. I always say, look, you can take ten medicines here, there’s one medicine that’s the best, that’s going for a walk’. (GP5). Two participants sometimes refer their patients or clients to another HCP working in nature (e.g., nature coach or ecotherapists): ‘When I notice that their self-care is very strongly linked to nature, I tend to send them to a nature coach. (…). Or people who are very reluctant towards psychologists … it is much less threatening than going to a (traditional) therapist’. (GP8). Finally, three participants take their patient or client into nature for several reasons. It can be easier to talk as it creates inner space: ‘It is stepping out of the dialogue, and going into nature. It is sometimes even more profound, or something can easier be said in nature while walking, than right in front of each other’. (PSY2). Or when oxygen is needed during the conversation, or the patient or client needs to be activated when depressed: ‘Once I worked with a patient with a trauma. I worked with her constantly in nature, and that has meant an incredible breakthrough in her development’. (GP1). For GPs at least, they need to organize their practice in such a way that this is possible.

4.2.4. Interrelationships between the topics

Several patterns arose when considering the interrelationships between the topics. First, attention is paid to both SC and RWN mainly during private time, and is hardly present during PP. Second, certain conditions must be met to make them both possible. At the same time the SC-paradox could also affect the RWN, as going into nature seems not to be an option when the conditions are not met. Consequently, given the combination of the SC-conditions, the SC-paradox (see 4.2.1) and the RWN-conditions (see 4.2.2), a certain complexity seems to arise in the interrelationship between SC and RWN which could jeopardize going out into nature. An interesting example of this complexity was clearly demonstrated during the Covid-19 pandemic. The condition of being alone was not met, and so nature visits decreased during this period: ‘Where my mom’s country house is, in the forest, there is a beautiful walk from Natuurpunt, where usually you are alone, but now you have to queue. Because of that we just don’t go there anymore’. (GP8). Finally, although some participants bring nature into their PP (see above), the depth of their own RWN is not disclosed during consultations. In contrast the invitation to visit nature is mainly limited to walks.

This study resulted in an overall pattern that we termed ‘nature-connected care awareness’ (NCCA), which may mediate the interrelationships discussed above. Participants mentioned that the interview and the second member-check step led to increased awareness and agency. For example, in the second step of the member-check, 11 of 14 participants replied to the question ‘What did you personally gain from the interview and the report?’ that they experienced it positively. ’Strengthening awareness’ (PSY4), ‘being inspired’ (PSY5), ‘encouraging me to …’ (GP1), ‘helping to reflect’ (GP2), described this experience more in detail. There also seemed to be a greater understanding of the interrelationships between SC, RWN and its possible implementation into PP: ‘I really liked the questionnaire about the ways in which nature can be used in healthcare (and self-care). To see it explicitly mentioned, makes you think about it more consciously. I feel inspired and will make more use of it’. (PSY5). In addition, some participants seemed to be stimulated into agency: ‘It encourages me to get out into nature more, to involve nature more in both my self-care and in caring for others!!! Nice reminder!’ (GP1).

Overall, this study suggests that NCCA, evoked by the participants’ reflexivity, could be an interesting facilitator in including an integrated, holistic and transdisciplinary health approach, such as OH, in PP with potential to become a role model.

5. Discussion

This exploratory qualitative study has shed light on how Belgian primary health care professionals (HCP) relate to the topics of self-care (SC), their relationship to nature (RWN) and its implementation into professional practice (PP). Also, we now have a greater understanding of how these topics and their interrelationships may be mediated by raising awareness, before coming to agency. After discussing the key findings, we discuss the implications for PP.

Firstly, the HCP appear to employ several SC strategies, mainly applied during private practice. However, whenever certain conditions are not met, several HCP fall into a SC-paradox, turning to ineffective SC strategies (for details see 4.2). Furthermore, at work, SC seems to be overlooked. Several studies have identified this discrepancy between private and professional practice (Bressi and Vaden, Reference Bressi and Vaden2017). However, those who manage to be aware of their SC during work mainly mentioned strategies such as time management, organizational strategies, and self-reflection. Studies have shown that being aware of and self-monitoring one’s needs play a role in effective SC (Posluns and Gall, Reference Posluns and Gall2020).

In discussing the topic of SC during the consultation, the HCP use various roles (examples are given in 4.2.3). In doing so, the HCP may use self-disclosure (SD) about what works for them. However, in this study we found only a few examples of RWN in SD.

Secondly, according to the findings in this study, RWN encompasses a continuum ranging from contact with nature (shallow experience) to connectedness with nature (deep experience), from an instrumental to a relational attitude towards nature, and from a unidirectional to a reciprocal relationship with nature. Within this continuum, one can experience various intensities and qualities of interactions with nature. Along the same lines, Lumber et al. (Reference Lumber, Richardson and Sheffield2017) and Ives et al. (Reference Ives, Giusti, Fischer, Abson, Klaniecki, Dorninger, Laudan, Barthel, Abernethy, Martín-López, Raymond, Kendal and von Wehrden2017) found several ways to interact with and experience nature. Like Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Dobson, Abson, Lumber, Hunt, Young and Moorhouse2020), we distinguish between contact with nature and connectedness with nature, which differ in emotional depth and type of relationship. The first assumes that nature is still something external to us, in which nature is perceived as a commodity that can be used, while the second is more relational, in which one might feel part of nature (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Frantz, Bruehlman-Senecal and Dolliver2009; Nisbet and Zelenski, Reference Nisbet and Zelenski2013; Tam, Reference Tam2013; Capaldi et al., Reference Capaldi, Dopko and Zelenski2014). In the case of the latter a more reciprocal, interdependent relationship with nature is present. From an ecopsychological point of view reciprocity means the relationship is characterized by an attitude of giving back to nature and making lifestyle choices which are beneficial to humans and nature at the same time.

When implementing RWN into PP, a discrepancy between private and professional practice arises here as well. Despite the various interactions and experiences with nature mentioned by the HCP, unlike the other SC strategies, they seem not to be disclosed during the consultation. Instead, nature-oriented invitations generally appear to be limited to nature walks rather than invitations to develop a deeper RWN. Discussing these distinct components of RWN with the HCP could provide insight and support in moving towards integrating for example a OH approach in both private and professional practice. Additionally, using a specific role as used with the SC topic could be a helpful tool to engage RWN during the consultation. These kind of roles, concretized by communication and coaching skills, are also used in psychotherapy and coaching. It could be an opportunity to include them in the HCP education curriculum when it comes to address specifically the RWN during the consultation.

Finally, the reflexive interviews and the member-check in this study have led to the participants’ raised awareness and agency regarding their SC, RWN and its implementation into PP. We have termed this ‘nature-connected care awareness’ (NCCA). We hypothesize that NCCA could be a facilitator in integrating, for example, the integrated, holistic and transdisciplinary OH approach into the PP, whilst becoming a role model. For example, GPs, based on their NCCA and knowledge of scientific evidence, could invite their patient to spend time in nature daily and explain how developing a reciprocal relationship with nature can improve well-being and care for nature, as found in OH and ecopsychology. An interesting example was mentioned by a GP in her thesis (Mortier De Borger et al., Reference Mortier De Borger, Keune and Peremans2022) of how she communicated with her patients: ‘Going into nature decreases stress hormones, and increases your energy level. For example, you go into nature for half an hour a day and for a total of two hours per week. You can walk, sit on a bench, read, chat, eat lunch, and more. In addition, you can enhance the health effects if you actively pay attention to the natural environment, such as listening to rustling leaves, bird calls, watching cloud formations, enjoying rays of the sun, or raindrops’. Furthermore, as a role model, HCP can give examples (self-disclosure) of how their RWN contributes to their health and care of nature and how these dimensions are intertwined. Similarly, when working in a healthcare organization, HCP, based on their NCCA, could operationalize a OH approach by considering (reciprocal) nature-based health interventions for their patients or clients, if appropriate. However, the quality of the design and implementation of such nature-based health interventions depend on quite some different actors. For example, when designing and implementing such an intervention, it would be advisable, as promoted by the OH approach, that HCP collaborate with other professional sectors (e.g., landscape architects, sustainability, human resources) and work transdisciplinary by involving multiple levels of the organization, stakeholders, and even patients or clients (Sterckx et al., Reference Sterckx, Van den Broeck, Remmen, Dekeirel, Hermans, Hesters, Daeseleire, Broes, Barton, Gladwell, Dandy, Connors, Lammel and Keune2021). Another aspect is that, hypothetically, NCCA and the operationalization of a OH approach in PP may support a so-called ‘instrumental and relational type of reciprocity’ in the human-nature health relationship. First, instrumental reciprocity arises from creating a biodiverse natural environment beneficial for human health, while at the same time, biodiversity supports the restoration of ecosystems. Second, HCP can stimulate a relational type of reciprocity when guiding their patients or clients in developing their RWN (e.g., nature connectedness), which could lead to healthy and ecological lifestyle choices and behaviors. For these reasons, we suggest that it would be useful to incorporate NCCA into the education curriculum of HCP, facilitating the inclusion of an integrated, holistic and transdisciplinary OH approach in PP.

5.1. Implications for professional practice

5.1.1. The self-care paradox

In our study we identified the so-called SC-paradox. In this case, adequate self-control, which has been mentioned in previous studies as a critical mediator in SC (Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Connelly, Pérez and Calero2021), seems to fail. The same applies to PP, where SC often takes a back seat while working.

Similarly, when it comes to RWN, the SC-paradox arises as well. If we consider developing the RWN as a possible SC strategy, a failure in self-control and a certain complexity might also occur when going into nature. In this case, many conditions or enablers have to be considered before a decision to go into nature may follow. For example, a person who would like to take care of themself by going into nature would have to simultaneously consider the conditions or enablers mediating SC and RWN. In that sense, we might assume conflicts between both may arise.

A previous study, focussing on self-control and exercise, emphasized the importance of having a long-term goal to maintain self-control. Self-control is understood here as ‘the mental capacity of an individual to alter, modify, change or override their impulses, desires, and habitual responses’ ( Reference Boat and CooperBoat and Cooper, 2019). In addition, a bi-directional relationship might emerge, in which regular training could even instill self-control (Boat and Cooper, Reference Boat and Cooper2019). The same could apply to the RWN. For example, a long-term goal (e.g., improving mental health) combined with regularly engaging with nature that opens the opportunity to deepen the RWN, could initially help overcome the SC-paradox. We expressly encourage the development of nature connectedness, beyond just walking in nature, as previous studies indicated that the latter would not deepen the person’s RWN (Lumber et al., Reference Lumber, Richardson and Sheffield2017; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Dobson, Abson, Lumber, Hunt, Young and Moorhouse2020). Likewise, we speculate whether deepening the RWN might promote a bi-directional relationship between self-control and RWN, thus overcoming the SC-paradox.

5.1.2 Self-disclosure and use of several roles: An opportunity for implementing the relationship with nature in the professional practice and in being a role model?

Our study showed that self-disclosure (SD) of the HCP during the consultation might occur, merely related to what works for them regarding SC. In contrast, personal interactions with nature and how it benefits them were generally not disclosed during the consultation. Although the value of the use of SD in a therapeutic or medical setting is a discussed and controversial theme in healthcare literature (Knox and Hill, Reference Knox and Hill2003; Arroll and Allen, Reference Arroll and Allen2015; Mann, Reference Mann2018) and most HCP are trained not to self-disclose (Arroll and Allen, Reference Arroll and Allen2015), studies show that SD is used by HCP under certain conditions (Arroll and Allen, Reference Arroll and Allen2015; Mann, Reference Mann2018). SD can be broadly defined as ‘therapist statements that reveal something personal about the therapist’ (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Knox and Pinto-Coelho2018). Despite the lack of consensus of its use, SD might be a helpful intervention when used in a skillful way, supported by guidelines, and trained in professional education (Knox and Hill, Reference Knox and Hill2003; Mann, Reference Mann2018).

Furthermore, previous studies have differentiated between verbal and non-verbal SD (Dean, Reference Dean2010; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Knox and Pinto-Coelho2018; Graham et al., Reference Graham and Weinman2019). In this study, it became clear that the verbal SD (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Knox and Pinto-Coelho2018) about his RWN experience and its benefits tend to be absent. Instead, HCP limit their nature-oriented suggestions to ‘a walk (in nature)’. Besides HCP having been trained not to self-disclose during consultation, another explanation could be that they try to maintain a split between personal and professional selves for SC-purposes (Søvold et al., Reference Søvold, Naslund, Kousoulis, Saxena, Qoronfleh, Grobler and Münter2021). SD requires HCP to be vulnerable and maintain their affective boundaries. Relating to nature might be experienced as a very personal and emotional matter, making its discussion difficult. Furthermore, the growing attention of the scientific and professional world to the nature-human-health nexus in recent years could indicate that this topic had previously been given little credibility. This fragmentation could be of concern since SD is an important pattern in being a role model (Knox and Hill, Reference Knox and Hill2003). Taking all this into account, the use of deliberate SD with careful thought in which HCP decide what exactly to disclose (Mann, Reference Mann2018) could be an opportunity to share his broader personal RWN experiences during the consultation. Combined with using several roles, as generally done for other SC strategies, HCP may engage in deep conversations with their patients or clients to explore a broader realm of nature experience, and inspire where necessary (Figure 4). For instance, using the role of ‘educating’, HCP could self-disclose how certain intensities and qualities of their RWN benefit themselves and why this is important in life and work. Then, for example, they could switch to the role of ‘researching’ and explore with their patient or client which kind of interactions with nature would be attractive. Furthermore, non-verbal SD, such as putting plants, nature pictures or magazines in the consultation room may also help HCP to act as a role model for their patients or clients.

Figure 4. Introducing the relationship with nature (RWN) into professional practice (PP) and being a role model, by using self-disclosure and roles.

Therefore, we suggest that the mere use of SD might offer an opportunity for being a role model for their patients or clients (Figure 4).

However, while pointing out that SD could be seen as an opportunity to introduce RWN to patients or clients, and thus used as an intervention (Graham et al., Reference Graham and Weinman2019), the conditions for its correct use (Knox and Hill, Reference Knox and Hill2003; Arroll and Allen, Reference Arroll and Allen2015; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Knox and Pinto-Coelho2018; Mann, Reference Mann2018) should be considered, such as the SD-type, the decision when not to disclose (Danzer, Reference Danzer2018) and its possible consequences. Therefore, we recommend that deliberate SD combined with the use of roles could be considered as a skill to be thoroughly trained during the professional education, when it comes to introducing the RWN into PP.

5.1.3. Fostering nature-connected care awareness as leverage in integrating nature into PP?

Cultivating a deeper RWN, such as nature-connectednes or a reciprocal relationship with nature, can lead to a greater well-being and living a meaningful life while caring for nature (Buzzell & Chalquist, Reference Buzzell and Chalquist2009; Zylstra et al., Reference Zylstra, Knight, Esler and Le Grange2014; Martin and Czellar, Reference Martin and Czellar2016; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Dobson, Abson, Lumber, Hunt, Young and Moorhouse2020). Our study showed that the implementation of RWN into PP is not a shared practice. First, the discrepancy between personal RWN and its implementation into PP could stand in the way of becoming a role model, as discussed above. Another explanation might lie in the possibility that HCP are simply unaware about the benefits of having a conversation with their patients or clients on RWN or about the possibility and the knowledge on how to prescribe nature. For instance, in this study, it turned out that according to the participants the reflexive conversations about the topics of SC, RWN and PP, led to increased awareness, inspiration and agency. Additionally, several participants mentioned that they are interested in the other participants’ views on SC and RWN as a way to mirror themselves and gain self-knowledge and inspiration as they struggle with these topics. Combined with the findings discussed above, we propose the following preliminary framework to raise NCCA, for facilitating the process of introducing RWN into PP and in becoming a role model (Figure 5). For example, to stimulate NCCA, reflexive conversations could be held about each topic. The barriers or enablers should also be discussed and how they might influence SC and RWN. Furthermore, becoming a role model can be conveyed through the use of verbal and non-verbal self-disclosure combined with the roles on addressing SC and RWN in PP. Additionally, although hypothetically, we could assume that raised NCCA could contribute to the more conscious employment of SC strategies and of RWN, and of how self-disclosure and roles can be used in introducing RWN into PP. However, more research is needed to confirm these bi-directional mechanisms. Interestingly, HCP could have the same conversation with their patients or clients and encourage SD, opening a space for deep conversation about RWN (Davidson, Reference Davidson2019) and helping in raising their NCCA.

Figure 5. Framework for healthcare professionals to raise Nature Connected Care Awareness.

The same could be true for integrating a OH approach into PP, which has been criticized for seeming to marginalize the perspectives of social sciences (e.g., psychology) (Roger et al., Reference Roger, Caron, Morand, Pedrono, de Garine-Wichatitsky, Chevalier, Tran, Gaidet, Figuié, de Visscher and Binot2016). Also, it could teach HCP how to communicate with their patients or clients about nature-connected care (NCC) so that it is better understood by both parties (Lapinski et al., Reference Lapinski, Funk and Moccia2015). As such, professional education curricula could consider integrating NCC and invite and teach HCP to do the same in their PP.

5.1.4. The changing role of the health care professional

Finally, given the findings in this study and the call on HCP to integrate NCC into their private and professional practice, this study could invite reflection on the critical societal and ethical issue related to the extending role and professional identity of HCP: What precisely does it mean to be one of these HCP today? Based on the findings and reflections in this study, the professional identity of HCP no longer appears to be limited to being caregivers for humans. Nowadays HCP seem invited to expand their professional identity with the following four components.

First, HCP could perceive SC as imperative (Barnett and Cooper, Reference Barnett and Cooper2009; Wright, Reference Wright2020) and an act of professionalism (Bressi and Vaden, Reference Bressi and Vaden2017; Wright, Reference Wright2020), and thus integrate it into their professional identity (Barnett and Cooper, Reference Barnett and Cooper2009). Personal and professional self should no longer be viewed as two separate aspects of self but as one whole (Bressi and Vaden, Reference Bressi and Vaden2017), serving the human-nature relationship.

Second, as a role model, the HCP could propose their patients or clients to develop RWN as a complementary health intervention. The Orem’s framework (Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Connelly, Pérez and Calero2021) in which the HCP, becoming an SC-agent practicing SC strategies, could help their patients or clients to do SC. Likewise, the HCP could become a ‘NCCA-agent’, using for example verbal and non-verbal self-disclosure and several roles to inspire their patients or clients while acting as a role model.

Third, due to their kind of work, HCP are confronted with ethical dilemmas. In this light, NCC could be perceived and included as an ethical dilemma in PP. For instance, in ecopsychology the person is perceived as part of nature, and thus the human-nature-health relationship is interdependent. In this light, new themes such as the RWN, climate change and ecological lifestyle could become part of reflexive conversations of HCP, which they could have between colleagues and with their patients or clients. In addition, sharing best practices between HCP could be helpful towards developing knowledge and agency. Therefore, communities of practice including collaborative reflective inquiry (Wesley and Buysse, Reference Wesley and Buysse2001) would be an interesting medium for HCP to raise their NCCA and to learn how to expand their professional roles.

Finally, HCP could practice reflexivity (Cunliffe, Reference Cunliffe2016; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Cunliffe and Easterby-Smith2019) to raise their NCCA, which might facilitate the integration of for example a OH approach. In addition, by developing a deeper, relational and reciprocal RWN and feeling part of nature, HCP could perceive their patient or client as a situated ecological and psychological being whose health depends on nature’s health and vice versa. Moreover, doing so could respond to the suggestion of the IPCC 2022 Mitigation of Climate Change report to enter an inner transition process, for instance, through raising awareness, changing beliefs, values and agency regarding the human-nature-health relationship (Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Logan, Bristow, Rozzi, Moodie, Redvers, Haahtela, Warber, Poland, Hancock and Berman2022). Professional education of HCP and public health associations could play a role in this transition and consider using our recommendations.

5.1.5. Strengths and limitations

This explorative study led to a preliminary framework to support HCP in fostering NCCA as a possible mediator of the interrelationships between SC, RWN and their implementation into PP (see Figure 4) and becoming a role model. However, further research to refine its findings and make them transferable on a broader scale is necessary. Nonetheless, the identified themes with their subsequent patterns are grounded in the data and were validated during the two-step member-checking.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations.

First, the fact that the HCP self-selected to participate makes the study susceptible to selection and response bias regarding the topic of SC, particularly since the study was held during the Covid-19 pandemic when SC was at stake in the healthcare sector. In addition, at the end of the interview, AS asked the participants who of their colleagues she could contact and with the specification: ‘colleagues who have and have not yet integrated their relationship with nature into professional practice'. Consequently, these references are based on the participant’s perception of someone’s RWN and are possibly biased. Thus, we infer that some participants have a positive relationship with nature in addition to the pandemic-related heightened interest in SC. Nevertheless, this approach resulted in a heterogeneous group of participants. This information is useful for comparison with similar studies that may be undertaken in other countries.

Second, due to a small sample, we have not compared the outcomes between the GPs and psychologists on the research questions. For example, in Belgium, a psychologist has generally a time slot of 45 min per client, which gives them the opportunity to go into nature with the client, when nature is nearby. In contrast, a GP typically works in 15–20 min time slots and this specifically asks for changes in his time management if he wants to go out into nature. Integrating nature in a GP’s profession requires far more effort for practical reasons alone. So, given this difference, system change, for example in the way GPs are paid and the length of time slots, should also be adapted. This shows that integrating nature into PP is a much more complex issue than just raising NCCA. Still, using self-disclosure and several roles in approaching SC and RWN in their PP could help HCP in becoming a role model and promote NCCA in their patients or clients. Other approaches and skills, not mentioned in this study (e.g., mindfulness), could also be explored further.

Third, AS is the principal investigator in this study. She is an ecopsychologist, Belgian representative of the International Ecopsychology SocietyFootnote 4 and owns a school to train facilitators to reconnect people with nature. Therefore, due to AS’ familiarity with the topics, bias cannot be ruled out when coding, interpretating and sharing the findings, However, AS adopted in this study a reflexive attitude (Berger, Reference Berger2015; Cunliffe, Reference Cunliffe2016). She practiced self-reflection on the quality of questions and reactions after each interview. Supervision and discussions with colleagues from similar and different backgrounds, using the two-step member-checking, and holding external validation checks with healthcare professional students have countered possible biases as much as possible.

5.1.6. Further research recommendations

SC and the RWN being both complex concepts, further research is needed. There are still many unanswered questions about their interrelationship and how it can be integrated into PP.

First, while there are studies on the identified discrepancies between private and professional practice in relation to SC, these could be further explored for RWN. For example, it would be interesting to learn how the SC-paradox might counteract RWN. Next, to become a role model, we propose further research on seeing oneself as a tool in PP by integrating SC and RWN into the professional identity of HCP. Regarding the integration of RWN into PP, further research could inform us about how and when the use of SD and roles are best applied, and the impact they have on the lives and work of their patients or clients. To our knowledge, there is no research on the use of SD and roles in relation to RWN by HCP. Deepening these insights could also contribute to a better understanding of the value of developing NCCA and how it could help to become a role model while integrating, for example, a OH approach into PP. In addition, it could lead to the development of guidelines to support HCP and public health organizations and inform the professional education of HCP. Finally, conducting a survey with a larger sample of HCP and comparing differences between GPs and psychologists, age, gender, and type of practice (e.g., private, public, group) might be interesting for future research.

Data availibility statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, AS. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to all participants in this study during the difficult period of Covid-19 pandemic. We thank Susan George, language coach (Linguapolis), for proofreading this paper.

Author contributions

AS conducted the research and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. KVDB, HK and RR critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

The University of Antwerp, Chair Care and the Natural Living Environment, which is funded by the Province of Antwerp, supported this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee Universal Hospital Antwerp EC/PM/AL/2020.060. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study and for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/one.2023.5

Comments

Dear Prof. Dr. Kock,We wish to submit an original research article entitled ‘Self-care and nature in the private and professional practice of healthcare professionals in Belgium’ for consideration by Research Directions One Health.We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.In this paper, we report on how primary healthcare professionals relate with self-care, their relationship with nature and its implementation into professional practice. We were prompted to conduct this study given the current social-ecological issues, climate change, public health problems, and overworked healthcare professionals suffering from mental health problems. Additionally, several scientific communities and international health organizations promoting an interdependent human-nature health perspective are calling upon healthcare professionals to incorporate this vision into their practice while at the same time becoming role models.Our explorative qualitative study has led to the proposal of a preliminary framework which could facilitate awareness and agency resulting from in-depth conversations with primary healthcare professionals on the topics of self-care, their relationship with nature and its implementation into professional practice. We have called this ‘nature-connected awareness’. In addition, organising communities of practice could facilitate the use of integrated health perspectives, such as One Health, into the professional practice and enable them to become a role models. Interestingly, the healthcare professional might have the same conversations with his audience, whilst employing various roles and using deliberate self-disclosure about his relationship with nature and its benefits, drawing on his experience in introducing the topic of self-care during the consultation. Therefore, we believe that this study is also relevant for (potential) One Health practitioners.We believe this manuscript is appropriate for publication by Research Directions One Health. First, because it relies on the same goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment. Second, we believe this study adds insight to the research question “One Health most often has people as the primary beneficiary. How must One Health policies and practice change to make animal, plant and ecosystem health a primary focus that is influenced by human and environmental factors?” We believe that adding an ecopsychological perspective to this question and using the preliminary framework to raise nature-connected care awareness and agency could assist One Health practitioners in this endeavour.Since this is a qualitative study, the word length exceeds the usual maximum of 5000 words yet remains comfortably inside the maximum of 5 figures and 7000 words.The manuscript has been carefully reviewed by an experienced native English academic writer.We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Please address all correspondence concerning this manuscript to me at ann.sterckx@uantwerpen.be.Thank you for your consideration of this manuscript. Sincerely,Ann Sterckx