Implementing evidence-informed deliberative processes in health technology assessment: a low income country perspective

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2020

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the potential feasibility and utility of evidence-informed deliberative processes (EPDs) in low income country (LIC) contexts. EDPs are implemented in high and middle income countries and thought to improve the quality, consistency, and transparency of decisions informed by health technology assessment (HTA). Together these would ultimately improve the legitimacy of any decision making process. We argue—based on our previous work and in light of the priority setting literature—that EDPs are relevant and feasible within LICs. The extreme lack of resources necessitates making tough decisions which may mean depriving populations of potentially valuable health technologies. It is critical that the decisions and the decision making bodies are perceived as fair and legitimate by the people that are most affected by the decisions. EDPs are well aligned with the political infrastructure in some LICs, which encourages public participation in decision making. Furthermore, many countries are committed to evidence-informed decision making. However, the application of EDPs may be hampered by the limited availability of evidence of good quality, lack of interest in transparency and accountability (in some LICs), limited capacity to conduct HTA, as well as limited time and financial resources to invest in a deliberative process. While EDPs would potentially benefit many LICs, mitigating the identified potential barriers would strengthen their applicability. We believe that implementation studies in LICs, documenting the contextualized enablers and barriers will facilitate the development of context specific improvement strategies for EDPs.

- Type

- Article Commentary

- Information

- International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care , Volume 36 , Issue 1 , 2020 , pp. 29 - 33

- Creative Commons

- This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use.

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2020

References

Table 1. Steps of EDPs

Table 2. Per capita expenditure on health

Table 3. HTA in low income and lower middle income countries (N = 38)

- 12

- Cited by

Evidence-informed deliberative processes (EDPs) are among the approaches that can be used to guide legitimate decision making using health technology assessment (HTA). EDPs emerged from two conceptual frameworks: multi-criteria decision analysis, which requires that decision makers explicitly identify the criteria they are going to use in the decision making process; as well as decide on how the different criteria are going to be considered; and the Accountability for Reasonableness framework (A4R) which provides four conditions (relevance, publicity, appeals and revisions, and enforcement) for fair and legitimate decision making (Reference Baltussen, Jansen and Mikkelsen1). Although both approaches emphasize the need for explicit criteria, A4R requires that “fair minded” stakeholders agree on the rationales for decisions and that the decisions are publicized. Furthermore, A4R requires the presence of revisions and enforcement mechanisms. EDPs have several underlying values and principles. For example, stakeholder participation and transparency of the processes are essential in all stages of decision making. The reasoning is that stakeholder participation and transparency contribute to legitimizing the institution, the process, and the decisions (Reference Daniels2).

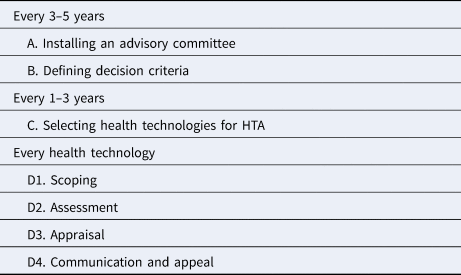

There are several merits in using EDPs in HTA; for example explicit identification and the use of decision criteria, participation of relevant stakeholders, transparency and legitimizing decisions, and capacity strengthening for decision making bodies. It is no wonder that EDPs are attracting international interest and have been used by HTA agencies in both high income and middle income countries (Reference Tromp, Prawiranegara and Siregar3). For this purpose, a practical guide has been developed consisting of several steps (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4) (Table 1)

Table 1. Steps of EDPs

Source: Oortwijn et al. (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4).

This paper critically reflects on the potential feasibility and utility of EDPs in low income countries (LICs), and identifies the opportunities for successful implementation. We also propose strategies through which potential barriers could be mitigated to support the successful implementation of EDPs in these contexts.

We first present a brief description of the context of decision making informed by HTA in LICs, and then, based on the EDP steps, we explicitly discuss the related opportunities and potential barriers. Lastly, we present mitigation strategies.

The Context of Decision Making in Low Income Countries

While there have been concerted efforts to strengthen and improve decision making processes in LICs, the political and economic contexts within which these decisions are made may facilitate or hinder legitimate decision making processes.

Politically, there is increasing pressure for more transparency and civic participation in decision making (5). As a result, many LICs have introduced norms and infrastructure that support transparency, participation of relevant stakeholders, and accountability of decision makers. For example, decentralization of decision making has been implemented. In many contexts, decentralization has involved devolving the decision making powers from the national level to sub-national levels, and a constitutional right for the public to participate in decision making (Reference Rondinelli, Nellis and Cheema6). Within the health sector, public health committees and health unit management committees have been established in many LICs as mechanisms to enhance public participation in population health and health services related decision making processes respectively (7;8). Such contexts are well aligned with approaches that require stakeholder participation.

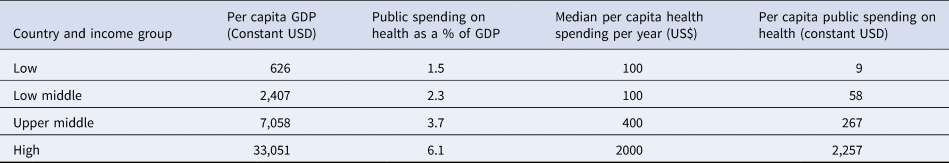

The economic context may also affect decision making. The health sector in LICs has historically operated on a limited budget. For example, according to a recent World Health organization (WHO) report, the poorest 10 countries spent less than US $30 annual per capita, which is too low to deliver a basic care package in order to reach Universal Health Coverage (Reference Watkins, Jamison, Mills, Jamison, Gelband and Horton9). Furthermore, the annual per capita spending on health remains very low and the median per capita health spending in LICs as well; this was estimated at $100 (1/20 of that of HICs) in 2016 (Table 2). The disease burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases also constrains the available resources (11). This scarcity often leads to unequal access to effective drugs and medical diagnostics, as well as poorly motivated human resources, which in turn affect the quality of services and health outcomes (Reference Kruk, Gage and Joseph12).

Table 2. Per capita expenditure on health

Source: Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Soucat and Kutzin10).

HTA in Low Income Countries

New health technologies continue to be introduced in LICs. For example, since 2010 108 out of 138 LICs, introduced at least one new vaccine (Reference Guignard, Praet and Jusot13). The introduction of such new health technologies requires HTA in order to set priorities. Recognizing this need, the WHO has supported the establishment of the National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs), which follow standardized and explicit decision making processes on vaccines. However, many of the NITAGs lack technical expertise and do not have access to credible evidence to conduct meaningful assessments. Moreover, NITAGs only focused on one type of technology (Reference Ba-Nguz, Shah and Bresee14), while there is a need for LICs to assess other health technologies as well. This is becoming increasingly important with the rate at which new health technologies (e.g. oncology drugs) are emerging. Such emerging technologies mean that LICs, similar to other countries, need to critically assess the existing health technologies that are being used, and make rational investment and disinvestment decisions. However, the level of institutionalization of HTA and capacity for conducting HTA remains rather limited (15).

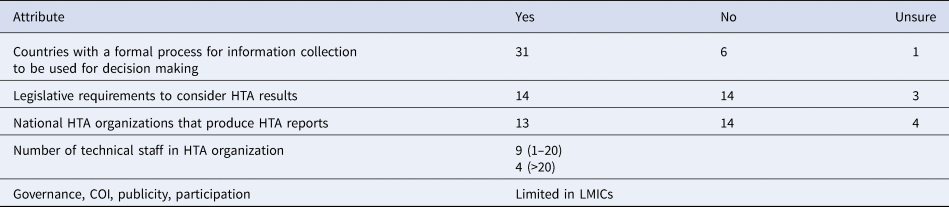

In a 2015 survey, which involved respondents from 12 LICs, eight reported the presence of some form of informal HTA activity within their countries, but they also reported to lack a formal and independent HTA organization (Reference Babigumira, Jenny, Bartlein and Garrison16). These findings were consistent with a WHO-led global survey of HTA organizations (15). The WHO survey intended to map out the existence, capacities, and requirements for HTA organizations and included respondents from 38 LICs (15). While both surveys covered several themes, those that are relevant to this paper include; (i) existence and capacities of the HTA organizations and (ii) barriers to the HTA process, and using the generated information for decision making in LICs. Key findings from the WHO survey related to LICs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. HTA in low income and lower middle income countries (N = 38)

Source: WHO (15).

Barriers to the HTA process included budget constraints, lack of information, limited awareness of HTA methods, and scarce human resource capacity. Barriers to using the generated HTA information included lack of awareness of the role of HTA, lack of HTA institutionalization, lack of clear mandate from legal and policy authority, limited political support, and limited human resources with HTA capacity (15). These findings are consistent with those from the other survey on HTA in LICs (Reference Babigumira, Jenny, Bartlein and Garrison16). Given these results, how might EDPs augment HTA in LICs?

Potential Contributions of EDPs in LICs

As discussed above, EDPs have been found to be useful in high and middle income countries. The framework's usefulness hinges on its being a product of two widely accepted and used frameworks (1;2) and it is highlighting good practices within the priority setting literature (Reference Kapiriri17). These factors contribute to the perception that EDPs can make meaningful contributions to strengthening HTA in LICs as well.

First, the approach recognizes the fact that HTA is political and value laded. It also recognizes the relevance of the context within which HTA is implemented (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). These are important considerations especially in LMIC contexts where, as noted above, the political and economic context may hamper even good processes. While it is beyond the scope of the HTA organization to influence the context, recognizing the politics of decision making and the relevance of the context may facilitate devising of pro-active mechanisms such as early engagement with key political decision makers, enlisting of and considering the social values within the context; which would facilitate wider stakeholder participation and political support as well as potential support for eventual decisions. These strategies may augment the successful implementation of HTA (Reference Kapiriri17).

Second, the EDP approach identifies the need for a designated advisory/expert/appraisal committee (with a wide stakeholder representation), whose responsibility it is to develop HTA recommendations (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). The emphasis on relevant stakeholder engagement in the process is critical to the legitimacy of any decision making processes (17;18), and would definitely benefit LIC decision makers and the public. Broad stakeholder participation in decision making may not be a foreign proposal especially for LICs with decentralized systems which encourage public participation in decision making. As discussed above, several of these countries have existing structures through which stakeholders can participate in health system decision making (Reference Panda and Thakur19). Hence the emphasis on stakeholder participation fits within already existing political and legal infrastructures of several LICs. This provides leverage and potential for this aspect of the EDP approach to be accepted, supported, and implementable within decentralized LICs.

Third, the EDP approach emphasizes the need for an explicit process through which the evidence and available options are appraised and deliberated on (Table 1). It further advises the advisory committee to enlisting explicit decision criteria that should be used as the basis for deliberations and when making HTA decisions. Unlike other approaches that emphasize cost-effectiveness as the most important decision criteria, almost at the expense of all other criteria, EDPs recognize that there are other relevant criteria that may be context specific that should be considered when making HTA related decisions. The criteria should not only reflect health system goals, but also societal values (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). The recognition of societal values as critical to informing priority setting is consistent with the literature on decision making in practice (17;18;20). This literature discusses priority setting as a political process in which the technical criteria may be in competition with societal values. In such instances, it is not uncommon to find that the significance of technical criteria is interpreted in the light of societal values when deciding to take action. Hence, the recommendation by the EDP approach that these criteria and rationales are made explicit and deliberated on would benefit many LICs as it could potentially limit the use of unacceptable and/or unfair criteria and rationales (Reference Ottersen and Norheim20). Furthermore, articulating the criteria and rationales would increase the consistency in decision making and the quality of the decisions. By not prescribing the criteria that should be used in all contexts, the EDP approach demonstrates their emphasis on contextualizing the HTA process. While some criteria such as effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are arguably relevant across contexts, some of the criteria may differ and so might the weight attributed to the different criteria (21). Allowing stakeholders to identify and prioritize the context-specific criteria recognizes their autonomy and is more likely to gain traction from the decision makers.

Fourth, EDPs emphasize the use of credible evidence when making HTA informed decisions (1;4). The role of evidence in any kind of health related decision making is well recognized and accepted in many countries. Global efforts such as the Global Burden of disease project, WHO CHOosing Interventions that are Cost Effective, the disease control priorities project have focused on generating evidence at the global level to inform decision making within countries (Reference Watkins, Norheim, Jha and Jamison22). Concurrently, there are local projects such as Evidence informed policy network, and supporting policy engagement for evidence based decisions focusing on developing and strengthening the use of evidence in policy making in LICs (23). These existing and already accepted initiatives are synergistic with the EDP approach.

Fifth, throughout the seven steps of the EDP framework (Table 1), there is an emphasis on ensuring that the decisions are legitimate (2;4). Legitimacy is a desirable attribute for any decision making body. Not only does it increase the acceptability of the decisions, it may also contribute to building of public trust and support for the decisions and the decision making institution (Reference Daniels2). In many LICs, the public has been disillusioned and have a distrust in the health sector. Trust has also been eroded reported instances of misappropriation of health sector funds, and poor quality services (24). Hence, decision makers within the health institutions need to rebuild trust and their public legitimacy. EDPs provide an avenue through which trust could be strengthened.

Lastly, the approach recognizes the need to link HTA to policy making. It also recognizes the need for capacity strengthening for HTA organizations; which, according to the literature on HTA, is a critical need in most LICs (15). Furthermore, a guidance document for designing and implementing EDPS is available, detailing the steps needed to achieve the proposed steps that EDP encompasses (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). The guide is concise, easy to follow, and practical. It provides examples from countries that have applied (some of) the proposed steps, relevant related references for anyone who desires to learn more about a particular step, and contact addresses which would enable anyone using the approach to consult with the developers should they find difficulties in applying the approach. Providing guidance as opposed to being directive and “owning the knowledge” is in line with the principles of respectful capacity strengthening and global health work (Reference Kapiriri17). Sustainability and institutionalization of any initiative requires that the implementers are enabled to eventually own the tools (Reference Kapiriri17). The step by step guidance provides the potential for the LIC users to customize the approach to their context and eventually own their process. This increases the potential for institutionalizing the approach.

However, although the framework provides relevant and critical synergies and guidance for HTA agencies in LICs, some factors may hamper the implementation of EDPs.

Critical Reflections on the Applicability of EDPs in Low Income Countries

First, EDPs recognize the merit of having a designated HTA organization. However, many LICs may lack such a formal HTA organization (15). LICs (and other countries) lacking a formal organizational structure for HTA would need guidance on how to set up an HTA organization before they implement the EDP approach. It is hence important for any implementer of EDPs to initially verify the existence of any HTA organization within a given context. In some LICs, HTA occurs informally or formally in specific organizations such as the NITAG for vaccines (Reference Ba-Nguz, Shah and Bresee14). In such cases implementing EDPs may necessitate flexibility whereby the implementers work with any institution that currently produces or uses evidence for decision making on new technologies. The idea of introducing EDPs then would be to systematize and strengthen the existing HTA processes, making explicit the implicit, and improving their legitimacy. This should be done concurrently with supporting the development and institutionalization of a national HTA organization.

Another factor that may hamper EDPs (and any other HTA approaches) is the limited availability of high quality evidence for decision making in many LICs. While there have been efforts to improve the evidence base for decision making in LICs (22;23), high quality evidence remains limited. Hence decision makers are left with the question of what to do in the absence of quality evidence (Reference Kapiriri17). The need for strengthening of health information systems within these contexts cannot be overemphasized. In the meantime though, pragmatic approaches might be considered, whereby the best available evidence is used, taking into account the uncertainty of the data.

A strength of EDPs is the emphasis on explicit deliberative processes, transparency, and legitimacy (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). There is a lot of support for these attributes in the literature, however, these may be complicated to implement in some contexts. While democratic countries emphasize and support stakeholder engagement and deliberative processes, these may not be supported in non-democratic countries (Reference Ottersen and Norheim20). Furthermore, research on priority setting reveals a game of shifting the blame, i.e. politicians shift the blame of rationing of health care to meso-level decision makers, who in turn shift that blame to frontline health providers. In such instances, there may be more desire for transparency by the frontline providers compared to politicians who are afraid of the public's response to the decisions (Reference Kapiriri17). This may require HTA organizations implementing EDPs to identify and engage with allies to facilitate political support the implementation of EDPs.

Furthermore, EDPs recommend that all stakeholders involved in the decision making process have equal opportunity to contribute and influence the decisions (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen4). However, HTA informed decisions tend to be highly political and could be easily influenced by strong persons and stakeholders. This may be more pronounced in LICs where resources are limited, whereby certain stakeholders (e.g. donors, manufacturers), who control the “purse strings” have been found to influence the introduction of new health technologies. Sometimes their influence may be driven by their own interests and may not necessarily be aligned with either the evidence or legitimate processes (13;17). Deliberative processes involving such stakeholders (e.g. when appraising the evidence and making recommendations) would require strong leadership of the individual chairing the deliberations to ensure power balance.

An additional constraint to implementing decisions made through systematic HTA processes such as EDPs in LICs relates to the fact that some LICs have accepted donated (especially diagnostic) technologies without assessment (Reference Guignard, Praet and Jusot13). Because some of the donated health technologies are not developed for use in the LIC contexts, they may require substantial financial and human resources for their operation and maintenance. This may lead to technologies not being used and “gathering dust” in the health facilities due to the lack of resources (Reference Kapiriri25). Addressing this anomaly would necessitate strong leadership and a legal framework to ensure that all donated technologies are evaluated before they are accepted. Although EDPs could provide guidance for the evaluation, its utility would be hampered in contexts that lack strong leadership, a legal framework and processes through which all donated technologies can be assessed.

Lastly, EDPs guidance stops at providing HTA recommendations. There is no provision for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) yet. M&E of the successful implementation of EDPs, and of the recommendations would further strengthen the HTA process. While it is most often beyond the scope of the HTA organization to ensure that their advice is acted on at the very least, there should be mechanisms for evaluating the degree to which the recommendations are implemented; reflecting on the enablers and barriers to implementation (Reference Kapiriri17). In this regard, the HTA organization could use process indicators such as the degree to which their recommendations are reflected in the policy documents, or inform and/or contribute to changes in policy (e.g. revising the basic health care package).

In addition to the implementation of the recommendations, it is important that HTA organizations monitor and evaluate the implementation of the EDP approach itself (Reference Kapiriri17). Based on this information, HTA organizations can devise improvement strategies and demonstrate the value added of using EDPs in improving the transparency, consistency, and quality of recommendations. When reflecting on the implementation of EDPs, evaluation could be aligned with the different EDP steps in order to identify where the bottlenecks are and design focused interventions. For example, monitoring and evaluating stakeholder engagement would involve: assessing which stakeholders are represented by designation, the degree to which each stakeholder actually contributes to the deliberations and stakeholders' satisfaction with the process. Monitoring should be done throughout the steps that require stakeholder participation. Observation at the relevant meetings and exit interviews with stakeholders after these meetings would provide real time information on the stakeholders' experience. This information would be invaluable in assessing the effectiveness of the deliberative process and for designing improvement strategies (Reference Kapiriri17). It is important that M&E is integrated throughout the EDPs to ensure a timely collection of the relevant information, enabling HTA organizations to design and implement improvement strategies during the implementation phase as opposed to waiting for formative evaluations (Reference Kapiriri17). Evaluation is critical in all contexts but more so in LMIC contexts where resources are even more limited. An assessment of the value of EDPs relative to the current approaches to decision making processes would facilitate buy in and increase the potential for its institutionalization.

Case studies evaluating the use of EDPs in the context of HTA in LICs will provide empirical information about the utility and feasibility of EDPs. Sharing of experiences across contexts in which EDPs have already been implemented would inform further refinement of EDPs.

Conclusions

EDPs have the potential to provide the necessary steps for legitimate decision making using HTA in LICs. Successful implementation and institutionalization of EDPs in LICs would be augmented by providing additional guidance on how to set up HTA organizations (for countries that lack designated HTA organizations) and considerations of how to deal with the lack of transparency and participation culture in some contexts. EDPs should integrate monitoring and evaluation to facilitate continuous learning and refining of the process, as well as its institutionalization.

Future research should focus on documenting actual implementation and evaluation of the use of EDPs in HTA in LICs.

Acknowledgements

LK was supported by a visiting scholar fellowship of the Netherlands Organization for scientific research (NWO). RB and WO were supported by a Vici grant of the Netherlands Organization for scientific research (NWO).