Which King Lear? The Texts and Their Dates

King Lear, a play about an unstable society, is itself an unstable text. For much of its theatrical history it has been adapted and altered, either because it was considered too difficult to perform as written or because it was felt to be artistically defective. It exists in two published versions (called a ‘History’ in 1608, a ‘Tragedy’ in 1623). The Lear published in 1623 differs from the earlier one in large ways – two scenes are omitted – and in a great many small ones, such as the spelling of characters’ names.Footnote 1 The reasons for these differences are still the subject of scholarly debate. The traditional view is that both derive from a common original and that the differences can be explained, on the one hand, by the incompetence of the printer in 1608 (he had never printed a play before) and, on the other, by alterations made by someone in the acting company and/or, later, by the editor employed to work on the massive 1623 Folio of Shakespeare’s collected plays.Footnote 2 Editors and directors who work on this assumption base their edition on both texts, making choices between them where they differ and thus producing what is really a third version.

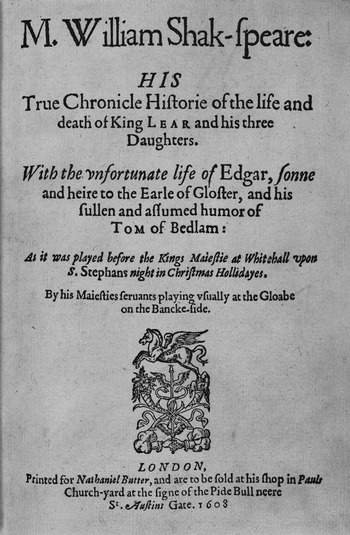

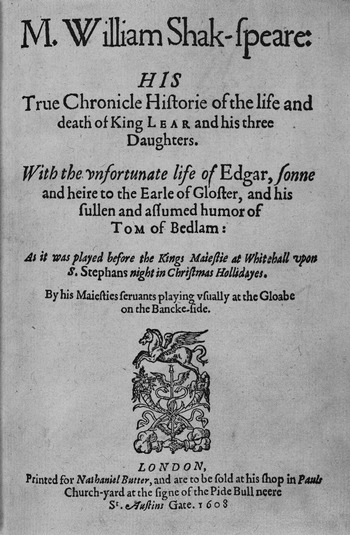

1 Title page of the 1608 quarto of King Lear. Leaf a4 recto: title page

2 First page of King Lear in the 1623 Folio. Leaf qq1 verso (page 280), leaf qq2 recto (page 283)

The other view is that the Folio represents Shakespeare’s revision of the quarto and that the two texts should be treated separately.Footnote 3 However, the word ‘revision’ may be misleading, if it means the author’s later, perhaps final, view of the play. As Leah Marcus writes, ‘These are two “local” versions of King Lear among other possible versions which may have existed in manuscript, promptbook, or performance without achieving the fixity of print.’Footnote 4 It is now recognized that plays were adapted for different occasions: they might be shortened for some performances and, for others, lengthened with songs and dances. For plays at court, actors were expected to be well dressed and spectacle was important, especially since some spectators, such as foreign ambassadors, would not know much English. Touring productions may have had fewer actors at their disposal; plays in private houses or at the Inns of Court (law schools) may have had their own requirements – for instance, long plays might have had a refreshment break in the middle. The early published versions of many of Shakespeare’s most popular plays – A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Hamlet, and Othello – differ from the ones published in 1623. We do not know whether the King Lear seen at court late in 1606 resembled the one published in 1608, or in the Folio of 1623, or neither. Tests of vocabulary and diction in the new material have suggested that it dates from around 1610, but the amount of text on which this conclusion is based is very small. Even if the changes were made around the time Shakespeare was writing Cymbeline (also based on early British history), the play remains an early Jacobean work rather than an example of ‘late Shakespeare’.Footnote 1

Whatever one thinks about the origins of the two texts, the argument for editing the quarto and Folio plays separately is that it enables readers to make their own decisions about the differences between them. This edition prints the text of the play as it appeared in the 1623 volume of Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. The first New Cambridge Shakespeare edition of this play, by Jay L. Halio, included a full discussion of these two texts. A slightly shortened version is reprinted here, introduced by Brian Gibbons, and the reader who wants to know more about this complex subject should look to pp. 50–79, 249–72. Passages that exist only in the quarto are printed in an Appendix.

The play’s date is less controversial. It must be later than 1603, which is the publication date of one of its sources, Samuel Harsnett’s Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures (see p. 8, below). The title page of the play’s first edition says that it was performed at the court of James I at Whitehall on 26 December 1606. It is possible that this was its first performance, though it is more likely that the actors had already played it in public or private locations. Gloucester seems to assume that his onstage and offstage listeners will know what he means by ‘These late [recent] eclipses in the sun and moon’ (1.2.91); he may or may not be referring to the eclipses that had taken place in September and October 1605.

The play’s most important theatrical source is an earlier play called The True Chronicle History of King Leir and His Three Daughters. This play (anonymous to us, but probably not to Shakespeare) could have been acted as early as 1589, and there are records of its performance at the Rose Theatre in April 1594 by a company that combined the personnel of two acting companies, the Queen’s Men and the Earl of Sussex’s Men. It was first entered into the Stationers’ Register in May 1594 (to establish ownership) but apparently not published; it was entered again in May 1605 and published later that year. Richard Knowles, who finds that Lear recalls Leir in ‘nearly a hundred significant details’, thinks that Shakespeare could have acquired such familiarity only from reading the published text and thus that his play must have been written mainly in 1606.Footnote 1 To many scholars, however, the echoes of Leir’s plot and language – which have been found in other Shakespeare plays as well – seem like the result of long acquaintance rather than recent skimming. Although there is no evidence that Shakespeare ever belonged to the Queen’s Men, several of their most popular plays became the basis for his own, and it remains possible that he saw or even acted in Leir when it was new.Footnote 2 The general view at present is that Shakespeare was probably writing King Lear in 1604–5 and planning Macbeth at about the same time.

Experiencing the Play

While King Lear is usually a gripping play in performance, it gets off to a difficult start. Its first scene, overloaded with characters and information, is difficult for an audience to take in. Actors notoriously find it difficult as well; Ian McKellen, who has played Lear several times, writes that he kept ‘saying to myself: Once upon a time there was a King with Three Daughters’ in order to believe in the improbable things he had to do.Footnote 3 The initial dialogue between Kent and Gloucester emphasizes Gloucester’s two sons, legitimate and illegitimate, who are then forgotten for some 270 lines. Lear’s plan to divide his kingdom among his daughters and their husbands is apparently known at least to these two courtiers, but his idea of basing his division on a ‘love-test’ may be either a secret plan or a sudden inspiration on his part. It is difficult for the five prospective heirs to the kingdom (and Cordelia’s two suitors, who enter later) to establish their characters and relationships in the few lines they are given. The love-test itself is an interpretive puzzle. The mood can be that of a lighthearted game, suddenly turning nasty when Cordelia refuses to play, or a deadly serious trial. Kent’s interruption gives the audience something like an outside perspective on the action. Since France and Burgundy are said to have been courting Cordelia for a ‘long’ time (1.1.42), productions sometimes indicate, as the text does not, whether she (or Lear) has a preference for either of them. Her departure as the future Queen of France can feel like a fairytale ending, but her farewell warning and the brief, hasty exchange between Gonerill and Regan suggest that there is more to come.

When the action shifts to Gloucester’s family and Edmond’s plot, Gloucester’s lament over the events at court keeps the Lear story in view. It also helps Edmond’s deception, since the old man thinks he sees a parallel between Lear’s unnatural treatment of his daughter and Edgar’s supposed plot against his father. The audience’s first look at Edgar is too brief to establish him as a counterweight to the attractive Edmond, whose plot takes effect with amazing speed. The action moves, like Lear, to the house of Gonerill and Albany, where Lear’s stipulation that he should always be attended by a hundred knights is infuriating Gonerill. Kent, disguised as a servant, is taken on by Lear and at once has a confrontation with Gonerill’s confidential servant Oswald. The Fool – the only major character not already seen – makes a surprise entrance and immediately dominates the stage. His increasingly bitter songs and jokes emphasize the breakdown of Lear’s relation with Gonerill, which reaches a climax when Lear calls down a curse on his daughter and storms out of her house. Act 1 (the Folio Lear, unlike the quarto, is divided into acts and scenes) ends with a short conversation between Gonerill and her bewildered husband Albany, whose allegiance is still unclear; Oswald and Kent are sent, separately, with letters to Regan; and the Fool tries to amuse the unhappy Lear and the audience before setting off with him to visit the second daughter. It is not clear whether Lear’s palace and the houses of Gonerill, Regan, and Gloucester are imagined as near each other.

From Act 2 onwards, everyone seems constantly on the move. Edgar is tricked by Edmond into fleeing from Gloucester’s house and is at once replaced by Regan and Cornwall, who have abandoned their own residence for reasons which at this point are obscure. They proceed to make themselves at home in Gloucester’s, even adopting Edmond in the process. Another confrontation between Kent and Oswald, which at first seems unmotivated, leads to Kent’s humiliating punishment in the stocks. Significantly (see note to 2.2.156), he probably remains visible, supposedly at Gloucester’s house, during the soliloquy in which Edgar, who has just fled from there, explains his intended disguise as an insane beggar. When Lear arrives, it finally becomes clear that Oswald’s arrival with a letter from Gonerill not only interrupted Kent’s delivery of Lear’s letter but also made Regan and Cornwall leave home at once. Lear has somehow learned of Regan’s whereabouts and come to Gloucester’s house, where, furious at the treatment of his messenger, he confronts Regan and Cornwall. When Gonerill arrives, and all three join forces against him, he is overwhelmed by the collapse of the world he thought he knew. Again, he rushes out of a house, this time saying, ‘I abjure all roofs’ (2.4.201).

Act 3, an extraordinary piece of writing, divides the characters into those outside in the storm and those who remain indoors. On the Elizabethan stage, all this movement would be indicated by long entrances and exits through the doors at the back of the stage. Thunder and lightning provide a background against which human voices can be hard to hear. Kent and the Fool have managed to find Lear; when they try to enter a shelter, they are confronted by the disguised Edgar as Poor Tom, mankind reduced to its lowest possible level, and the sight precipitates Lear’s descent into madness. Gloucester finds somewhere for them to go in, but almost at once returns to warn them to go out again, carrying the sleeping Lear. The Fool is never seen again. Running parallel to the scenes of Lear’s madness are the quieter ones in Gloucester’s house, where Edmond betrays his father. The blinding of Gloucester (3.7) is the most shocking event of the play, but also a turning point. Cornwall’s servant, revolted by the act, kills his master; Gloucester finally learns the truth about his two sons. But the servant himself is killed and Gloucester’s knowledge only adds to his wretchedness. Most productions put the interval either just before or just after this scene, as Gloucester is thrown out of his own house.

In Act 4, everyone seems to be converging on Dover, but characters frequently meet each other on the way in unspecified locations. When Edgar leads his blinded father onto the stage, the audience, like Gloucester, has to take his word that they are approaching Dover Cliff. Gloucester attempts suicide by jumping from it but Edgar has deceived him (and perhaps some of the audience) in the hope of curing his despair. Lear rejoins them, but the dialogue between mad king and blind man, another high point of the play, ends abruptly when Lear runs away from the soldiers sent by Cordelia to rescue him. Meanwhile, short scenes have indicated the crumbling of the alliance among Lear’s enemies: Albany is estranged from Gonerill; Cornwall’s death has made Regan a dangerous rival for Edmond’s love. Gloucester has a price on his head, so Oswald, now travelling with a letter from Gonerill to Edmond, tries to kill the old man. He is killed by Edgar, who discovers the incriminating documents that he was carrying. The act ends with the great scene in which Lear awakes in Cordelia’s presence, gradually recognizes her, and asks her forgiveness. Like her departure for France in 1.1, her insistence that she has nothing to forgive seems about to bring the story to a happy ending.

Throughout the first four acts, there has been talk of war, first between Albany and Cornwall, then between France and England – or, rather, between supporters of Lear, helped by a French army, and the armies of Albany and Edmond, who has replaced Cornwall as general. Act 5 finally brings the battle that everyone has been expecting, and, as often noted, it is an anticlimax. Possibly Shakespeare was avoiding the dramatization of a French invasion of England; possibly this part of the play depended on spectacle that would have been worked out in rehearsal rather than recorded in the text. Modern productions often depict the battle only through sound effects, heard by the blind Gloucester. He is finally led away by Edgar, who has seen the defeat of Lear’s forces.

Unlike the battle, the trial by combat between Edgar and Edmond ends with victory for the ‘right’ side and with the one genuinely effective revelation in the play – ‘My name is Edgar, and thy father’s son’ (5.3.159). But Edmond’s defeat, which leads to the exposure and death of Gonerill, shows evil destroying itself (Gonerill has already poisoned Regan). Albany has the women’s bodies brought on stage to make this visible for the audience and the other characters. Edmond belatedly tries to undo his worst action, ordering the deaths of Lear and Cordelia, and is taken to die, like his father, offstage. The subplot is finished, and Edgar remains as an appalled spectator when Lear’s entrance with the dead Cordelia shows that there will be no victory for good. As in the opening scene, the king is with his daughters, urging Cordelia to speak. Perhaps, as he dies, he thinks she is about to answer him, but the meaning of his last words is mysterious. A sense of exhaustion hangs over the survivors. Albany, technically the heir to the throne, apparently attempts to divide his kingdom between Kent and Edgar (but does ‘rule in this realm’ mean the whole of Britain, or only part of it?). Neither explicitly consents (unless the ‘we’ in Edgar’s final speech is a royal we). Kent exits, saying that he will follow Lear in death, and the concluding couplets may be deliberately flat. What do we feel? What ought we to say?

Contexts

Public Events

James I had arrived from Scotland in the summer of 1603. King Lear, like Macbeth, belongs to the period when Shakespeare and his colleagues were looking for the right kind of play for a new king and a new court. This meant, among other things, a movement away from English history, in which the Scots often figured as villains, and towards ‘British’ or classical history, likely to be more familiar not only to the Scots but also to visiting foreign dignitaries. The play’s apparently casual opening line – ‘I thought the king had more affected the Duke of Albany than Cornwall’ – must have attracted attention at the court performance in 1606, since the king’s sons, Henry and Charles, had recently been given these titles. In the play, they apparently refer to Scotland and Wales (with England presumably intended as Cordelia’s portion), though the exact boundaries are left deliberately vague. But Gloucester’s reply, with its reference to ‘the division of the kingdom’ (1.1.3–4), would have been still more significant. James’s reuniting of the crowns of England and Scotland had already been celebrated officially; the play will show its audience the fatal moment at which Britain was divided. The word ‘British’, as used in Lear, not only refers to the period in which the play is set but also has topical significance. James wanted to unite his kingdom under the name of ‘Great Britain’ – something that would not officially happen for another 100 years.Footnote 1 Albany was Prince Charles’s Scottish title, and the Duke of Albany is given the play’s last lines in the quarto, perhaps foreshadowing Scotland’s later importance; the lines were given to Edgar in the Folio, perhaps because this point no longer needed to be made.

Leah Marcus has pointed out that St Stephen’s Night, when the play was given at court, was associated with hospitality and charity (it was the day when poor boxes in churches were broken open and the money distributed to the poor). The fact that the 1608 title page makes a point of the performance date might, she thinks, alert readers to a way of reading the play, with its references to beggars and the homeless.Footnote 1 The version printed in 1623 does not make this connection, since the Folio, though it emphasizes Shakespeare’s close relationship with the King’s Men, omits references to performance conditions. Published twenty years after James’s accession (and only two years before his death), the Folio Lear was already becoming a less topical work.

The public theatres were closed because of plague between 5 October and 15 December 1605, and November saw the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament – the result of the disappointment and anger of some Roman Catholics who had hoped that the change of reigns might lead to greater toleration for their religion. In the circumstances, it is unlikely that Shakespeare could have finished the play, or that his company could have rehearsed it, in time for the Christmas season of court performances in 1605–6. Even without this traumatic event, religion was a major topic of discussion at the time of Lear’s first performance. The king’s reign had begun with a conference about religion at Hampton Court (January 1604), and the commissioning of a new translation of the Bible. The measures that Gloucester takes to keep Edgar from leaving the country (‘All ports I’ll bar’: 2.1.79) are like those taken against the plotters and their supporters.

One of the play’s odder sources, Samuel Harsnett’s Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures, is an anti-Catholic polemic. The author revisits an episode of 1585–6, recently investigated again, in which Roman Catholic priests had claimed to exorcise servants suffering from demonic possession. He argues that the susceptible servants, mainly women, had been led to give spectacular accounts of their sufferings by the suggestions of their interrogators. It was from this book that Shakespeare took the names of the devils by whom ‘Poor Tom’ claims to have been possessed, and the situation of the servants in their chair (something Harsnett insists on several times) may have helped to create the awful image of Gloucester bound to a chair and tortured. The name Edmund (or Edmunds) occurs frequently in Harsnett’s account; however, both Edmund and Edgar were also the names of kings before the Norman Conquest.

In 1603–4, there had been a curious parallel to the story of Lear. The elderly Sir Brian Annesley had three daughters, though only two were involved in the legal battle over whether he was too senile to be allowed to act for himself; the one who argued that his wishes deserved respect was, significantly, named Cordell. When Sir Brian died in 1604, one of the executors of his will was a man probably known to Shakespeare, Sir William Harvey, husband of the Countess of Southampton, who later married Cordell himself (her father had left her everything). It is not likely that this episode inspired Shakespeare’s play, or even the name of the heroine, since there are other sources for both, but Shakespeare may have been struck by the way in which life sometimes imitated art.

Literary and Theatrical Influences

Knowing the sources of Lear is perhaps as close as one can ever come to observing the creative process by which Shakespeare made his play. It can also help to avoid unnecessary questions, such as, ‘Why doesn’t Cordelia just tell her father what he wants to hear?’ The basic starting point – the king who asks his three daughters to say how much they love him – was not Shakespeare’s invention. Many cultures have a story about someone who asks his three children how much they love him, fails to appreciate the honest answer of (always) the youngest one, and eventually realizes that she or he was right.

The ‘chronicle histories’ that served as sources for many plays in the 1590s tended to make up for the absence of hard facts with traditional anecdotes, especially for the poorly documented earlier periods. Geoffrey of Monmouth, in Historica Anglicana (c. 1135), was the first to connect the love-test with the division of the kingdom, and to ascribe it to a King Lear. There was no historical Leir or Lear: his name may have been invented to explain the name of the town of Leicester, interpreted as the Roman fort (caster) of Leir (compare Old King Cole, supposedly resident at Colchester). According to Geoffrey, Cordelia led an army that restored Lear to his throne, and became queen after his death. Later, her sisters’ children rebelled and threw her into prison, where she hanged herself. This story is retold in The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1587), published under the name of Raphael Holinshed. This was probably Shakespeare’s main source but he could also have read a condensed account in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590). Another popular work was The Mirror for Magistrates (1574), a series of verse monologues by various writers in which the ghosts of famous people describe their miserable fates. It includes Cordelia’s account of her imprisonment and suicide.

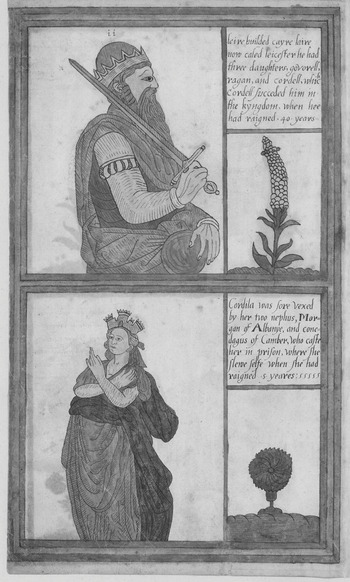

3 Thomas Trevelyon, Leire and Cordila [Trevelyon Miscellany], 1608. Folio 73 verso

By calling itself The True Chronicle History, the anonymous Leir play acknowledges its indebtedness to sources like these, but gives events a romantic and folkloric turn, ending with Leir’s restoration to his throne. Tolstoy, in a famous essay, said that it was superior to Shakespeare’s version.Footnote 1 Certainly, it tells its story more clearly than Shakespeare does, partly because it has no subplot. Although there is no Fool, there are a number of comic characters and scenes; despite some harrowing and pathetic moments, there is rarely much doubt that the story will end happily and that virtue will be rewarded.

In the Leir play, as in Holinshed, all three daughters are unmarried at the beginning, but the love-test is designed to trap Cordella, who has said that she wants to marry for love: once she professes her love, Leir plans to make her prove it by marrying the man of his choice. Since the two older sisters have already been tipped off that their father plans to marry them to the men they prefer, they have no hesitation in expressing unconditional love and obedience; Cordella, however, defeats his plan by refusing to flatter him. The king of ‘Gallia’ (France – but the name perhaps emphasizes how long ago all this is happening) visits England in disguise in order to find out whether English women are as pretty as he has heard; he meets the banished Cordella and falls in love at once. Meanwhile, Leir’s other daughters show their evil natures: Ragan pays someone to kill her father and his loyal friend Perillus, but the murderer is frightened off by heaven’s thunder. In desperation, the two old men travel to France, where they meet Cordella and her husband, again in disguise, and have a touching reunion. The author handles the tricky problem of dramatizing a successful French invasion by making it comic. All the characters trade pre-battle insults; there is plenty of onstage fighting; the sisters’ husbands run away; and Leir, a wiser man, is restored to his throne. It is made clear that the Gallian king is there only on Leir’s behalf and that he and Cordella will return to France at once.

As Janet Clare has pointed out, the title page of the 1608 edition of Lear ‘advertised its relationship and continuity with the recently published Leir play’.Footnote 1 It also emphasized its difference: this version of The Chronicle History of King Lear is by William Shakespeare, depicts not only the life but also the death of the king, and includes new material. This statement was necessary, because the Stationers’ Company (the equivalent of a publishers’ and printers’ union) protected its members by making it difficult for anyone to publish a work that was likely to duplicate and thus damage the sales of one already in existence. The emphasis on the role of Edgar also ensured that prospective readers and spectators would not be expecting just another retelling of a story they already knew.

The subplot involving Gloucester and his two sons reinforced the theme of parent–child relations and provided more good roles for the company’s actors. Shakespeare based it on an episode in one of the most prestigious and popular works of the Renaissance, Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia (first published in 1590). Two young princes are sheltering from a storm when they overhear a young man arguing with an old, blind man. The old man turns out to be the king of Paphlagonia, whose son has refused to lead him to the top of a rock, realizing that his father wants to throw himself off. As in Lear, the king has previously been deceived by his bastard son, though Sidney’s characters do not explain (as Shakespeare’s play does) how the deception was carried out. The two princes intervene, restore the old man to his throne, and reward his virtuous son, though this happy ending is as temporary as the happy ending of Cordelia’s story in the chronicles. As Geoffrey Bullough has shown in his massive source study, Shakespeare drew on more than one part of the novel, as well as on its fatalism and its serious debates about the meaning of life. Perhaps, too, the spectacular storm that opens this episode suggested the one in Lear.Footnote 2

Among Shakespeare’s own works, the plays most often compared with Lear are Titus Andronicus, an early work, and Timon of Athens, probably begun around the same time as Lear but left unfinished. Both plays have a Fool or Clown among the characters, and a hero who sometimes sounds like Lear in his rage.Footnote 3 But Lear also resembles the comedy As You Like It, acted around 1600 but not printed until 1623. The song that a courtier sings in the Forest of Arden –

– sounds as if it belongs in King Lear rather than in a comedy where ingratitude is not a prominent theme. When Kent tells Lear that ‘Freedom lives hence, and banishment is here’ (1.1.175), he echoes Celia’s claim that she and Rosalind, in leaving the court, will go ‘To liberty and not to banishment’ (AYLI 1.3.138).Footnote 1 Structurally, too, both plays have several ‘false endings’. In As You Like It, these take the form of rhyming couplets and a cue for dance, twice interrupted; in Lear, Albany makes similar unsuccessful attempts to draw the play to an end. The brief snatch of song from Lear’s Fool, ‘He that has and a little tiny wit’ (3.2.72), echoes the Fool’s final song in Twelfth Night (1601).

King Lear is the only one of Shakespeare’s major tragedies to make use of disguise, which, as Peter Hyland has noted, is used primarily in comedy and tragicomedy (including the comic scenes in the chronicle histories).Footnote 2 The old King Leir included several disguised characters, though not the same ones as in Lear. A character in disguise usually gains power by knowing something that others don’t, and the disguises of Kent and Edgar create the expectation that they will bring about a happy ending – as in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure and John Marston’s The Malcontent, both of which are usually dated 1603–4. Yet the disguises in Lear result mainly in humiliation and Edgar’s final triumph rings hollow.

Another comedy – Eastward Ho! (1605) – has also been suggested as a source.Footnote 3 This collaboration by George Chapman, Ben Jonson, and John Marston contains several joking references to Hamlet, as well as an obvious parody of a line from Richard III, so it is likely that Shakespeare would have wanted to see or at least read it. The resemblances that Gary Taylor finds in Lear (an ironically inverted father–daughter relationship; the wildness of the apprentice Quicksilver, which resembles Edgar’s narrative of his past as Poor Tom; the importance of a storm at the centre of the play; and an improvised trial scene) may be – like the echoes of the old Leir play – Shakespeare’s transformation of theatrically striking moments in a new context. But the dates of the two plays are uncertain; the influence may have worked either way.

If the literary sources of the play, apart from the Arcadia, are essentially comic, the ‘historical’ accounts contain tragic events. Lear apparently dies of old age, but Cordelia’s suicide in a state of despair would, to a Christian reader, have condemned her to hell, which is why Alexander Leggatt argues that murder is a ‘more merciful’ end for her than suicide.Footnote 1 The old Leir play ended happily because it ended before that point. Shakespeare did not really turn a comedy into a tragedy, as is often said; he compressed the events of many years into a play. Moreover, the design of this early Jacobean play requires the division of the kingdom to have disastrous consequences. The implication (though most people are unlikely to have believed it, even in 1606) is that the happy ending, a thousand years in the future, will be James I.

Afterlife: In the Theatre

Early Responses

The lack of surviving contemporary reaction to King Lear makes it difficult to know whether its first audiences took it as a political work or simply as a powerful theatrical experience. Richard Burbage was the leading actor of the King’s Men, and Lear is mentioned as one of his roles in an elegy on his death.Footnote 2 The line ‘And my poor fool is hanged’ (see the note on 5.3.279) has led some scholars to think that the parts of Cordelia and the Fool were doubled by a boy actor, while others believe that Robert Armin, who had recently joined the company, played the Fool. Armin, short and ugly, was a clever actor who also wrote plays and, in 1608, perhaps to accompany Lear’s appearance in print, published a book on fools called A Nest of Ninnies. William A. Ringler, however, has argued for the Fool–Cordelia doubling, on the grounds that Armin’s versatility made him better suited to Edgar.Footnote 3 The fact that many female roles in the major tragedies are those of mature women suggests that the company now had older boy actors who were convincing in these roles. The smallness of Cordelia’s part may be due to its being written for a new, less experienced boy. There is one other casting possibility. In English drama, Lear’s most obvious influence was on John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (1613). Bosola, a villain with a conscience, echoes both Lear and the Arcadia in describing life as ‘a shadow or deep pit of darkness’ and claiming that ‘we are merely the stars’ tennis balls’. To a dying man, he murmurs, ‘Break, heart!’ in an obvious echo of Kent’s words over the dying Lear: ‘Break, heart, I prithee break’ (5.3.286). This line is given to Lear in the quarto, but Webster must have heard it spoken by Kent in the theatre (as it is in the Folio). John Lowin, a leading actor in the King’s Men, played Bosola; he may have played Kent as well.

In 1609–10, a King Lear play was performed at a private house in Yorkshire. It might have been the old Leir, but it is more likely that the company chose the one published in 1608, which would have been new to a provincial audience. The actors got into trouble for putting on a play about Saint Christopher, and their patron was suspected of Catholicism. Stephen Greenblatt suggests that they must have felt that Lear, despite its use of the anti-Catholic Harsnett, ‘was not hostile, was strangely sympathetic even, to the situation of persecuted Catholics’.Footnote 1 A play called Lear König in Englelandt, presumably based on Shakespeare’s, was performed by an English company in Dresden (a Protestant city) on 26 September 1626. It was never printed, but, if it was like other surviving German versions of English plays, it would have been heavily cut, with emphasis on the mad scenes and clowning.

The public theatres were closed at the start of the English Civil War in 1642 and remained closed until the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. Sir William Davenant, one of the two theatre managers appointed at that time, had his company perform the play in 1664 and 1675. Unfortunately, Samuel Pepys did not see it, and there are no records of its reception – which suggests that it was unsuccessful. In 1681, however, the same company performed an adaptation by the poet and dramatist Nahum Tate, with the finest actor of the age, Thomas Betterton, as Lear. This version, which is also the first conflation of quarto and Folio,Footnote 2 became the acting text for the next 150 years.

Nahum Tate’s Adaptation, 1681–1838, and After

Although Tate used to be mentioned only as an object of ridicule, many of his changes not only reflect the taste of the late seventeenth century but also represent good playwriting practice. Theatres after 1660 were using representational scenery (painted on flats) and hence found it difficult to stage a series of short scenes like those in Acts 3 and 4. Women had replaced boys in female roles, and needed to be given more to do. Like many modern directors, Tate cut and conflated minor characters. He also removed one major one, the Fool – and not only because the character had become old-fashioned. As Sonia Massai points out (p. 436), his disappearance removed ‘the main source of the vexing criticism the king is exposed to in the Shakespeare originals’. The newly restored monarchy had every reason to be nervous about such criticism.

Tate’s main innovation was to create a romantic relationship between Edgar and Cordelia, a decision that turned Cordelia’s small part into an important one. She now has a motive for defying her father in the first scene, in order to avoid marrying Burgundy (the King of France, obviously, is not part of this play, so Cordelia never leaves the country). Lear also has a better motive for his anger against her, since he believes the negative view of Edgar that Edmond has disseminated (Massai, pp. 437–8). Edgar himself is so distracted by his concern for Cordelia that he is easily duped by Edmond, and he remains in the country to watch over her. Because he has a recognizable personality before he goes into disguise, the audience is not confused by his Poor Tom impersonation.

In this context, there was no doubt as to the evil of Gonerill and Regan. Although for the first two acts they maintain that their quarrel is with Lear’s entourage, not with him, a common practice among rebels in the English history plays (and Parliament in the 1630s) was to claim that they wanted only to remove the corrupt favourites around the ruler. Edmond’s relations with the sisters are those of a Restoration rake, but he also lusts after Cordelia and sends ruffians to carry her off, so that Edgar is able to rescue her and prove his worth. Tate set the final scene in prison where Lear, asleep with his head in Cordelia’s lap, is finally able to enjoy, as he had hoped in 1.1, ‘her kind nursery’. The audience sees the old man heroically fighting off the murderers sent by Edmond, and his exhausted collapse afterwards was one of the highpoints of eighteenth-century performances. Albany and Edgar arrive with rescue just in time, and Lear abdicates in favour of Edgar and Cordelia. Tate retained two of the play’s most shocking scenes, the blinding of Gloucester and his attempt to throw himself off a non-existent cliff. By the eighteenth century, however, the blinding was happening off stage, where it seems to have remained until well into the twentieth century. Developing a hint in Shakespeare (4.4.12–13), Tate made Gloucester decide to use the spectacle of his blindness to raise a popular rebellion against the sisters. Kent, whose role in the second half of Shakespeare’s play is disappointingly subdued, becomes the leader of Cordelia’s army. These changes create their own difficulties: Gloucester’s energy seems inconsistent with his desire for death, and, the more emphasis there is on the rallying of Lear’s forces, the harder it is to understand why the wrong side wins. Royalists in Restoration England may, however, have seen the defeat of Lear’s cause as a parallel to their own in the recent Civil War. The ending, with its emphasis on restoration, was equally significant. ‘By making Lear both the “Martyr-King” and the restored king, Tate reverses the act of regicide.’Footnote 1 In 1681, when the childless Charles II was being urged to divert the succession from his Roman Catholic brother James to his illegitimate son, the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, no one could miss the relevance of a play in which a villainous bastard plots to disinherit his brother. In 1688, other political events made the conclusion too awkwardly topical. Facing rebellion, James II fled to France and was replaced by his daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange. He was declared to have abdicated (like Lear, in favour of a daughter and son-in-law), though in fact he and his successors made several attempts to regain the throne. One of his supporters accused Mary of being ‘worse than cruel, lustful Goneril’.Footnote 2 Tate’s Lear was not performed again until five years after Mary’s death in 1694.

4 Anonymous artist, ‘King Lear, act V, scene the Prison [III], as perform’d by Mr. Barry & Mrs. Dancer at the Theatre Royal in the Haymarket’

It was largely David Garrick’s playing of the role, from 1742 to his retirement in 1776, that made it a popular success. By the end of that period, however, the editing of Shakespeare’s text was becoming a high-profile activity and there were calls for the original play to be performed. Garrick’s marked-up acting copy, now in the British Library, shows that in the course of his career he removed some of the Restoration language and restored 255 lines of the original. Nevertheless, the play still ended with Lear’s heroic fight, the last-minute rescue, and the happy ending of the love story. Francis Gentleman’s notes to Bell’s Shakespeare (1774), the acting edition used in the London theatres, were obviously written with Garrick’s performance in mind; they emphasize the pathos in the role and the opportunities for a versatile actor in the king’s rapid transitions of mood.Footnote 3

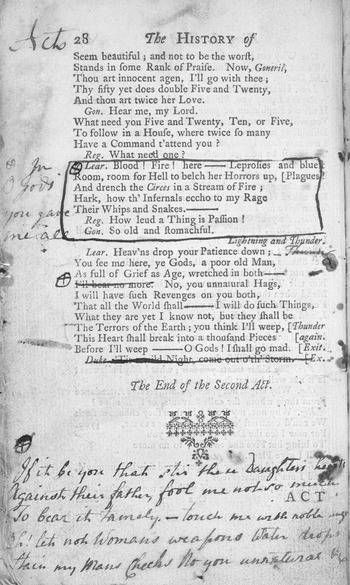

5 Page from David Garrick’s copy of the acting text, showing his additions and alterations to the Tate version

The play again became uncomfortably topical when, in 1788, George III began showing signs of insanity. In a letter of 18 December 1788, recently published online, a doctor informed the Prince of Wales that his father had been ‘agitated and confused, perhaps from having been permitted to read King Lear’.Footnote 4 The king may even have tricked his doctors into giving him the play.Footnote 5 Though he recovered from this attack, in 1811 his condition became permanent, and Lear was not performed again until after his death in 1820, when both London theatres rushed to revive it. The great actor of the Romantic period, Edmund Kean, played Lear successfully in that year, and his literary friends persuaded him to try the tragic ending in 1823, but it was a failure.

Kean’s most important successor, William Charles Macready, played a tragic version (though still without the Fool) in 1834, but in 1838 he revived the play, heavily cut and rearranged, omitting all of Tate’s lines and restoring the Fool. There were difficulties: actors found it hard to learn a new text, and his new leading lady, Helena Faucit, was reluctant to take the much reduced role of Cordelia. When Macready worried that the Fool ‘will either weary and annoy or distract the spectator’ someone suggested that the part should be played by a woman.Footnote 1 Though later revivals did not necessarily follow this example, they generally depicted the Fool as frail and wistful, cutting his bawdier lines. The restoration of the original text went along with historical sets and costumes that placed the play’s events in a more ‘primitive’ age. Though Lear was still treated as a pathetic figure, Macready also found ‘a heartiness, and even jollity in his blither moments, in no way akin to the helplessness of senility’.Footnote 2 The comedy, of course, was in the service of a sympathetic characterization. The Tate version continued to have a life in America until Edwin Booth played a condensed but totally Shakespearean version in 1875.

Lear in Europe before 1900

In the eighteenth century, as Shakespeare began to be known outside the Anglophone world, the early French and German translators felt free to adapt a play which had already been adapted. The German version published in 1778 was by the actor Friedrich Schröder, who based it on an accurate prose translation by C. M. Wieland (1762). Unlike Tate, he retained the Fool, a character type that had remained popular in central Europe, and he omitted the Edgar–Cordelia love affair. Some of his changes were minor improvements. Lear asks the disguised Kent’s name when they first meet, so that the audience isn’t confused by hearing him called Caius at the very end of the play.Footnote 3 Edgar is not quite so easily manipulated as in Shakespeare. Other changes reduce the number of characters and scene changes. 1.1 is cut: Kent simply tells Gloucester about the love-test and his banishment. Thus, Kordelia does not appear until Act 4 and her role is greatly reduced.

Schröder, who had great success in the role of Lear, departs most from the original in his treatment of the ending. As in Tate’s version, the final scene takes place in prison, where Lear, who has never recovered his sanity, fantasizes about singing ‘like birds in the cage’, and puts an imaginary Gonerill and Regan on trial. Though he kills the soldier who is trying to hang Kordelia, she faints; thinking that she is dead, he dies of grief, while she apparently survives to become Queen of England. Even Goethe, who produced the play at Weimar in 1796 and 1800, believed that Schröder had the right idea about staging Shakespeare, whose numerous scene changes he considered impossible.

Because of the international dominance of French in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the very different Lear (or Léar) of Jean-François Ducis was still more influential. Ducis, though he knew no English, had access to a better Shakespeare translation than for his earlier Hamlet and Othello. His version was performed in 1783 before Louis XVI at Versailles and was the first Shakespeare play acted at the Comédie Française. Following his usual practice, Ducis reduced the size of the cast, changed the names of some characters, and, like Schröder, opened the play after its most improbable episode, the love-test, had already taken place. He omitted the subplot but gave Kent two sons, both virtuous, who fight to restore Léar. What this version retained above all were the spectacular effect of characters speaking against the background of a storm and the touching reunion of the feeble and confused Léar with his daughter. Still more than in Tate, the emphasis is on family relationships: when Helmonde (Cordelia), prompting Léar’s memory, asks him whether he was a king, he replies, ‘No, but I was a father.’Footnote 1 The omission of the subplot gives room for an even more prolonged display of madness than in Schröder, continuing into the inevitable prison scene; Léar finally recovers when he hears that Helmonde has been saved from death.

At a time when English was still not widely known, translators in other countries often followed the French or German adaptation. Although a fuller translation of the play by Josef Schreyvogel was performed in Vienna’s Burgtheater in 1822, the censor insisted that Lear and Cordelia must be allowed to live. Rather than rewrite the final scene, the translator followed the Shakespeare text until Lear said ‘Look there!’ – ‘only to have Cordelia revive and the curtain descend on the rapturous reunion of father and daughter’.Footnote 2 Even when, late in the century, the play finally included Cordelia’s death, ‘it seemed merely a natural step towards their final reunification’ (Williams, German Stage, p. 126). Ira Aldridge, the great African-American actor, played Lear in whiteface on the European continent and in provincial English theatres between 1858 and his death in 1867. Reviewers saw him as ‘a just and kind king who … is blinded and confused by his good nature’.Footnote 3 When he played in non-anglophone countries, he used a heavily cut text; it apparently included the love between Edgar and Cordelia, though in some performances at least he also played Lear’s death scene.Footnote 4

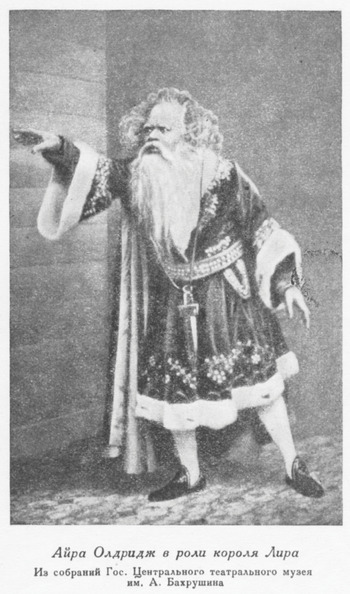

6 Ira Aldridge as Lear, c. 1860, in white make-up

Both translation and scholarship on Shakespeare developed rapidly during the nineteenth century, particularly in Germany. Important evidence about the Elizabethan theatre came from the discovery in Utrecht in 1880 of what is usually called the ‘Swan drawing’, a rare surviving view of an Elizabethan playhouse interior. In 1889, a newly designed auditorium in Munich’s Residenztheater, later known as the Shakespeare Stage, gave Lear as its first production, showing how a permanent set could enable rapid movement from scene to scene.Footnote 5 It was not an accurate reconstruction, but it inspired many other attempts at ‘Elizabethan’ methods. The twentieth century would find other ways – technical advances in scenery and lighting, an unlocalized stage – to speed up performances and thus enable the playing of a fuller text.

7 Lear’s denunciation of Cordelia, as played at Munich’s ‘Elizabethan’ theatre, c. 1890, on a semi-permanent set, with the ‘early English’ costumes typical of nineteenth-century productions

The Roles: Changing Perspectives since 1900

Lear

Audiences once expected ‘cosmic grandeur’ from the actor of Lear, particularly in the curse on Gonerill and the storm scene. This phrase, though it might have applied to many Lears, was in fact used by Edith Sitwell about Donald Wolfit in 1940. However, it seemed ‘an outdated idea’ to Michael Pennington when he wrote in 2016 about the experience of playing Lear himself.Footnote 1 For one thing, political – and especially feminist – criticism tends to be hostile to Lear, at least in the early part of the play. Moreover, very few productions are now, like Wolfit’s, dominated by an actor who is also the director. In Anglophone productions at least, directors are now likely to care more about the family story than the ‘cosmic’ one, and to attempt to do justice to all the characters. Nevertheless, Lear continues to dominate discussions of the play, and reviews still focus largely on the actor who plays the part.

Richard Burbage was probably about 40 when he first played Lear; Garrick was 25, Gielgud 27. For them, the part of the 80-year-old king was simply one more feat of impersonation (an actor playing someone totally unlike himself). Now, Lear is often played by actors at the peak of their careers, implying a kind of identity between actor and role. Laurence Olivier (who first played Lear in 1946) appeared in a television version in 1983, when he was 75 and terminally ill. Some of the effect of Robert Stephens’s Lear in 1993 was due to his obvious frailty (he died two years later).Footnote 1 William Hutt, who played a famous King Lear at Canada’s Stratford in 1988, appeared in the television series Slings and Arrows in 2006 at the age of 86, as an ageing actor who wants to play the part yet again.Footnote 2 Audiences who know the age of the actor playing Lear will watch with awe if he carries the dead Cordelia onto the stage. Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser (1980) depicts the worry this causes for an old actor (‘Sir’) playing Lear. Gregory Doran at the first rehearsal of the Lear he directed in 2016 quoted the advice ‘Get a Cordelia you can carry’, attributing it to Donald Wolfit, the prototype for ‘Sir’.Footnote 1 Many of Shakespeare’s tragedies give the leading actor some opportunity at the end to impress the audience by fighting, as with Romeo, Richard III, Hamlet, and Macbeth. With the disappearance of Tate’s version, Lear’s heroic fight also disappeared, and, while rehearsing the role, Oliver Ford Davies wondered, ‘Has the carrying on of Cordelia become the most famous piece of stage business in Shakespeare, the ultimate test of an ageing actor’s virility?’Footnote 2 For an audience more involved in the story, however, Lear’s entrance is both a shock and a moment of almost unbearable pain.

8 ‘Howl, howl, howl, howl’: Colm Feore as King Lear and Sara Farb as Cordelia (background: Victor Ertmanis)

Garrick’s Lear was, he said, based on his observation of an old man who had gone mad after accidentally killing a beloved child. Many actors since his time have also felt the need to study real examples of mental illness. Macready, knowing the frequency of mad scenes in the major theatrical roles, forced himself at the beginning of his career to visit an asylum and drew on his vivid memories when he played Lear.Footnote 3 Productions in the twenty-first century reflect increasing awareness of an ageing population’s vulnerability to dementia. In Australia, according to Philippa Kelly, medical professionals speak of ‘The King Lear syndrome’ and society ‘increasingly understands what it might feel like to be Goneril, Regan and Edmund, and to fear what it is like to be Lear or Gloucester’.Footnote 4

In some productions, Lear shows symptoms of insanity from the beginning. Christopher Plummer’s Lear (Stratford, Ontario, 2002) had trouble remembering the word ‘Burgundy’ in the opening scene, and in 4.6 his slurred speech suggested that he had had a stroke.Footnote 5 However, Alzheimer’s is an irreversible condition, whereas the scene (4.6) in which Lear finally recognizes Cordelia is usually seen as the beginning of a return to sanity, though in a state of diminished energy (the doctor says that the ‘great rage’ has been ‘killed’ in him: 4.6.77–8). Simon Russell Beale researched mental illnesses before his performance at the National Theatre in 2014 and concluded that the king was suffering from the condition known as ‘dementia with Lewys Bodies’, characterized by restlessness and hallucinations like Lear’s vision of ‘the little dogs and all’ barking at him. A doctor who reviewed the production, however, thought that Lear seemed less mad in the final scene than in Act 1.Footnote 6 Ian Stuart-Hamilton, the psychologist who talked to Antony Sher during rehearsals of Gregory Doran’s King Lear (2016), argued that Lear at the beginning was capable of making plans and in good health, and his later behaviour could be explained as delirium resulting from fever and exposure to the elements.Footnote 1 Thus, his earlier fears of madness might be either emotional blackmail (‘I prithee, daughter, do not make me mad’: 2.4.211) or genuine fear of Alzheimer’s. Lear himself recognizes the symptoms of hysterica passio (see notes to 2.4.52–3 and 2.4.114). The Lear of David Warner (Chichester, 2005) died, literally, of a broken heart,Footnote 2 as did Kevin McNally at the Globe in 2016.

The Fool

The relation of the Fool and Lear is almost symbiotic: Antony Sher, one of a number of actors who have played both characters in the course of their careers, writes that ‘the two performances have to grow together in rehearsals’.Footnote 3 Perhaps for this reason, most Lear actors, though they call the Fool ‘boy’, do not want him to be boyish, and many Fools have been nearly as old as Lear.Footnote 4 But women are also cast in the role – for example, Linda Kerr Scott (RSC) and Emma Thompson (Renaissance Theatre Company), both in 1990 – and some performers, such as Ruth Wilson (New York, 2019), have doubled the role with Cordelia, as some think was the original practice. The early modern Fool was instantly recognizable by his costume, which, as David Wiles explains, consisted of motley clothing, a cockscomb (substitute crown), and a bauble (substitute sceptre).Footnote 5 In a modern-dress production, he may look like a music hall performer or red-nosed circus clown. Much of his humour depends on puns that are too ingenious for a modern audience – see this edition’s notes on ‘Take the fool with thee’ (1.4.270) and ‘cruel garters’ (2.4.7) – so he usually needs to have other performance skills.

9 ‘Poor fool and knave’: Kent (Louis Hillyer), Lear (Corin Redgrave), and Fool (John Normington). Royal Shakespeare Company 2004, directed by Bill Alexander

Directors are often tempted to bring him on in the opening scene, playing games with the king or watching, appalled, as Lear destroys his kingdom. The Fool in Irving’s 1892 production reverently kissed the hem of Cordelia’s robe as she departed.Footnote 1 But, as Oliver Ford Davies points out, ‘the three mentions Lear makes of the Fool early in 1.4 are a deliberate build up to his first grand entrance. The Jacobean audience would have anticipated a turn, and the Fool obliges by dominating the scene for nearly a hundred lines.’Footnote 2

Since the Fool was both a character and a recognized part of the acting company, his disappearance halfway through the play may not have needed an explanation. Critics point out that both Edgar and Lear take over his role, and this idea can be conveyed in performance: John Normington (RSC, 2004) handed Poor Tom his distinctive cap and bauble, walking not only off the set but out of the play. At a time when it was assumed that Lear’s ‘my poor fool is hanged’ (5.3.279) referred to him rather than Cordelia, he was sometimes seen twisting a rope into a noose; suicide is still given as an explanation for his disappearance. In Adrian Noble’s RSC production of 1982/3, Lear killed the Fool in his madness, an idea that has been taken up by other directors. In a Georgian production, a tyrannical Lear deliberately killed the Fool ‘for mocking him’.Footnote 3 In Max Stafford-Clark’s Royal Court production (1993), the Fool re-appeared in Act 5 and was hanged by soldiers for spraying subversive graffiti.Footnote 4 Munby’s 2018 Lear brought the lights up for the interval just as the Fool was apparently about to be killed by Edmond. Some directors, such as Grigory Kozintsev in his film version, cannot bear to let the Fool disappear. Sher, as Lear, wanted to retain an echo of the character, so he illustrated his line about ‘this great stage of fools’ with a bit of the Fool’s characteristic dance.Footnote 5

Gonerill, Regan, and Cordelia

In the old Leir play, all three daughters are unmarried at the start. In Lear, the two older ones seem to have been married for some time, though they have not yet received their dowries, and both appear to be childless. They are often depicted as considerably older than Cordelia, though when Lear curses Gonerill with sterility he must assume that she is still capable of childbearing.Footnote 6 When they were assumed to be unproblematically evil from the beginning, they, and the women who played them, received very little critical attention. The theatre historian A. C. Sprague noted that there is a great deal of information about how famous actors before 1900 delivered the curse on Gonerill, but virtually nothing about how she reacted to it.Footnote 1 A review by Francis Gentleman in 1770 says only, of the two sisters, that it would be ‘a coarse compliment to say any ladies looked or played them thoroughly in character’.Footnote 2 Reluctance to be identified with vicious characters may have resulted in rather subdued performances.

Gonerill and Regan often used to look evil from the start. On the page, they can seem almost alike when they take part in their competition for Lear’s love, but in performance they can be differentiated quite sharply.Footnote 3 Psychological readings often begin with birth order: Gonerill, the oldest, usually takes the initiative, while Regan builds on what others have said: ‘she names my very deed of love. / Only she comes too short … ’ (1.1.66–7). Directors usually have more sympathy for Gonerill, at least in Act 1. Gonerill and Albany often seem to have a virtually sexless marriage, but in Rupert Goold’s production (Liverpool and Young Vic, 2008–9) Gonerill was pregnant: ‘Cursed by its grandfather while still in the womb, the baby was born in parallel motion to the storm scene.’Footnote 4 Regan may be weaker; Judi Dench gave her a stammer in 1976 (RSC), supposedly the result of a childhood of intimidation by her father. A statue of Lear towered over the daughters in the 2014 National Theatre production, perhaps to explain the extraordinary viciousness of Anna Maxwell Martin’s Regan, who appeared sexually excited by the torturing of Gloucester. Jonathan Pryce’s Lear (Almeida, 2012) suggested incestuous feelings towards his two older daughters.Footnote 5

10 ‘But goes thy heart with this?’ Lear (John Gielgud) in a ‘Renaissance’ setting, with Gonerill (Cathleen Nesbit), Regan (Fay Compton), and Cordelia (Jessica Tandy). Old Vic, 1940, directed by Lewis Casson and Harley Granville-Barker

11 Lear (Simon Russell Beale) under his statue with Gonerill (Kate Fleetwood), Regan (Anna Maxwell Martin), and Cordelia (Olivia Vinall). National Theatre, 2014, directed by Sam Mendes

Cordelia leaves the play after the first scene and re-appears only in Act 4. When a production cuts all her asides, as is sometimes done in the interest of realism, her small role becomes even smaller and her behaviour even more abrupt. In Gregory Doran’s production of 2016, she was something of a spoiled child: her speech ridiculing the idea of loving her father at the expense of her husband was made with the confidence of a woman used to finding approval, and it drew sympathetic laughter from the other characters, making Lear’s violent response all the more shocking. Depending on how the King of France is played – Lear’s later description of him as ‘hot-blooded’ (2.4.205) is rarely borne out in performance – it can seem strange that her only later mention of him is as ‘great France’ who has allowed her to bring an army to fight for her father. A few productions have tried to show how their marriage turned out, by bringing him back with her to England (giving him the lines of the Doctor) or by depicting her as pregnant (as at Glasgow Citizens’, 2012).

Gloucester, Edgar, and Edmond

When Gloucester’s blinding took place off stage, as happened before the twentieth century, it was possible for critics to claim that he suffers less than Lear because his suffering is ‘only’ physical rather than mental. No one is likely to say this after seeing most modern productions, where the blinding is depicted with horrible realism. Sometimes, it even encourages audience laughter. In Gale Edwards’s production in Adelaide, Australia, in 1988, ‘the sensationally gory balls representing Gloucester’s eyes were flung into the wings after his blinding’. Like Peter Brook, Edwards took the interval at this point, ‘leaving the audience to dwell on what they had just laughed at’.Footnote 1

Because of Gloucester’s offensively flippant references in 1.1. to his adultery and his son, he is often played as a tyrannical father or as a fool. Surprisingly few productions play up his heroism (‘If I die for it – as no less is threatened me – the king my old master must be relieved’: 3.3.14–16), and even fewer make anything of the rapidity with which, when he learns of Edmond’s treachery, he repents his own ‘folly’ towards Edgar and prays the ‘Kind gods’ to ‘forgive me that, and prosper him’ (3.7.91). Nahum Tate gave him a moving speech on his blindness, inspired by the opening of Book iii of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and allowed him to join Lear in retirement instead of dying.

Scholarly opinion is divided as to whether the scene of Gloucester’s attempted suicide is meant to fool the audience as well as Gloucester, though Edgar is given lines that should make the deception clear (‘I do trifle thus with his despair’, 4.5.33, and ‘Had he been where he thought’, 4.5.44). The uncertainty is, of course, possible only on a stage without representational scenery, or in a film that controls what the audience can see. Brook’s film version used ‘only close shots … so the naïve spectator would have no way of knowing Edgar’s plan until a long shot after Gloster’s fall’.Footnote 2 In the 1998 film of Richard Eyre’s National Theatre production (1997), the two actors moved in a fog that made it impossible to know where they were. The stylized background of Deborah Warner’s 2016 production was equally ambiguous. Though early modern cures for madness sometimes suggest playing along with the delusions of the sufferer, many critics see nothing but cruelty in Edgar’s behaviour. It has been suggested that he is indulging in a fantasy of both killing and saving the father who has rejected him.Footnote 1

12 ‘Alive or dead?’: the ‘Dover cliff’ scene, with Gloucester (Karl Johnson) and Edgar (Harry Melling). Old Vic, 2016, directed by Deborah Warner

As Ian McKellen has written, Edgar is a very difficult role and Edmond an easy one,Footnote 2 but the latter usually gets better reviews, because of his humour and the fact that he confides in the audience. He becomes most complex in his last minutes, with the ambiguous ‘Yet Edmond was beloved’, but his last-minute repentance is often cut in order to speed up the ending. Although Edgar’s poetic linking of Gloucester’s blindness with ‘the dark and vicious place’ where Edmond was conceived has been condemned as self-righteous moralizing, Edmond himself accepts it, adding another traditional image, Fortune’s wheel, to symbolize his situation.

An eighteenth-century audience would have been aware of Edgar the romantic lover behind Poor Tom, and may even have found the impersonation comic, since, as Francis Gentleman writes, ‘feigned madness always caricatures real’.Footnote 3 In the Shakespeare text, the audience hardly knows Edgar before he takes on the role, and does not always appreciate the virtuoso performance of his various identities. His absence from the opening scene may mean that the actor had to double as France or Burgundy. Modern productions sometimes include him; Simon Russell Beale’s Edgar (RSC, 1993) was seen reading a book while awaiting Lear’s arrival. Otherwise, his first appearance in 1.2 may show him, at one extreme, in serious study or, at the other, reeling in from a night on the town. Either way, the lunatic is so much more vivid than the young aristocrat who impersonates him that Simon Palfrey, who has devoted a whole book to Poor Tom, suggests that the fictitious character is eerily interwoven with the ‘real’ one throughout the play; Edgar is ‘not so much a character as a nest of possibilities’.Footnote 1

The Knights, Kent, and Oswald

Lear’s initial stipulation of a hundred knights would not have seemed odd at a time when aristocratic households contained a vast hierarchy of retainers. Given the importance of ‘attendants’ for establishing a character’s status, it is likely that the Jacobean stage always had more people on it than one expects to see now. Theatres well into the twentieth century could press extras into service, including some who were recruited on the afternoon of the performance: Henry Irving, in 1892, had sixty on stage in the opening scene. In 2016, Gregory Doran had twenty-four ‘supernumeraries’ for his RSC Lear. Gonerill’s complaints seem more justified when the stage is full of knights than when this entourage is represented only by the single knight with a speaking part. Peter Brook made these characters rowdy and violent in 1962 and they have been getting steadily worse: Trevor Nunn in 2007 and Jonathan Munby in 2018 had them carry off one of Gonerill’s female servants to be raped.

Kent and Oswald, both loyal servants, used to be regarded as moral opposites. Coleridge described Kent as ‘the nearest to perfect goodness of all Shakespeare’s characters’, and Oswald as ‘the only character of utter unredeemable baseness in Shakespeare’.Footnote 2 When Macready wrote that the actor playing Kent ‘requires powers for comedy and tragedy’,Footnote 3 he was thinking mainly of the character’s interactions with Oswald in 1.3 and 2.4, which, in some eighteenth- and nineteenth-century productions, went on for much longer than one would guess from the text. Oswald had further opportunities for clowning when Kent was safely in the stocks – apparently a ‘farcical’ punishment rather than a painful one.Footnote 4 If Francis Gentleman is representative of attitudes in 1774, they were extremely class-based: he objected to Kent’s defiant behaviour in 2.4 (‘Such conduct in presence of a sovereign prince is intolerable’) but reported that Edgar’s killing of Oswald ‘never fails to create laughter’ (Bell’s Shakespeare, 65n.) Directors now are more likely to agree with an influential comment by Bertolt Brecht in the 1950s: ‘What you cannot have is the audience, including those who happen to be servants themselves, taking Lear’s side to such an extent that they applaud when a servant gets beaten for carrying out his mistress’s orders.’Footnote 1 Modern productions rarely discard the comedy altogether, but they often stress the resemblance as much as the difference between the two characters.

Afterlife: Critical and Creative Responses

The Tragic Experience: Philosophy and Religion

In his introduction to the 1972 Arden edition of King Lear, Kenneth Muir wrote that the Romantic poets and critics had arrived at ‘a conception of the play not essentially different from that generally held today’.Footnote 2 Keats’s sonnet ‘On sitting down to read King Lear once again’ (1818) brilliantly embodies this conception as, in his opening lines, he turns away from romance to something completely different:

This expectation that reading King Lear will be a consuming, painful, and life-changing experience is characteristic of a writer for whom Shakespeare was Scripture. It is also, as Muir says, characteristic of many readers and spectators of the play up to the time when he was writing, and probably still represents what most people want to find in it. To be burned by a literary work is to undergo catharsis, the famous and much discussed word that Aristotle used to explain the almost visceral reaction that great tragedy can evoke. The word evokes both purification and purging, and Aristotle seems to have thought that it should result in the acceptance of a supernatural order. This assumption has been questioned for much of the last century.

Keats’s description of the play as a ‘fierce dispute, / Betwixt damnation and impassion’d clay’ implies a serious questioning of the situation of mortal humanity faced with a very real sense of evil. The word ‘evil’ seems somewhat excessive, when it is first used by Kent to Lear:

What he means by ‘evil’ might be Lear’s decision to give up his rule to Gonerill and Regan, or his treatment of Cordelia, or even the violence he has just shown (in some productions, the reference to ‘my throat’ follows Lear’s attempt to throttle him). Cordelia does not use the word, and her reference to her sisters’ ‘faults’, which she is reluctant to call by their right names (1.1.265), may apply simply to their flattery of their father. The play contains examples of what might be called normal moral dishonesty: after she has heard from Gonerill, Regan travels hastily to Gloucester’s home so that she doesn’t have to deal with Lear at her own residence; Edmond also leaves home at a crucial point, apparently ignoring the appalling implications of Cornwall’s suggestion that ‘The revenges we are bound to take upon your traitorous father are not fit for your beholding’ (3.7.7–8). But nothing can explain the speed with which Gonerill and Regan go from irritation, to anger, to the chilling line (however it is spoken) ‘O sir, you are old’ (2.4.138, then to the smug claim that being out in the storm will teach him a lesson (2.4.295–7), and finally to Gloucester’s report that they ‘seek his death’ (3.4.147). Perhaps the turning point comes when Cornwall calls to have Kent put in the stocks, saying, ‘there shall he sit till noon’, and Regan, building as usual on what others have said, corrects him: ‘Till noon? Till night, my lord, and all night too’ (2.2.122–3). By this time, the word ‘evil’ seems totally appropriate: ‘What begins as common sense opens out into a terrifying blankness of moral idiocy.’Footnote 1

It is possible to quote lines from King Lear to support almost any religious or philosophical outlook. Since it is supposedly set in pre-Christian times, Shakespeare can make Kent retort to Lear’s ‘by Apollo’ with ‘Now by Apollo, king, / Thou swear’st thy gods in vain’ (1.1.154–5) without being accused of blasphemy. It can be argued that Shakespeare is deliberately depicting the horror of a world without Christianity, or, on the other hand, that ‘the gods’ who inflict so much cruelty are really ‘God’. Cordelia’s self-sacrificing love has led some to call her a Christ-figure and some of her words have biblical overtones (see the note to 4.3.23–4). Gloucester’s astrological fatalism is ridiculed by Edmond but echoed by Kent, though only in the quarto, as a way of explaining the different moral characters of three children with the same parents.Footnote 2 Gloucester, when he prays to the gods, calls them ‘kind’ (3.7.91) and ‘ever gentle’ (4.5.208), perhaps in the folk belief that one must flatter them in order to get an answer to one’s prayers. In the most famous lines of the play, he says that they treat human beings as inhumanely as boys treat flies (4.1.36–7).

Many religions are based on the idea that the events of this world seem unjust only when one is unable to perceive them in a spiritual context. A. C. Bradley’s summary of what he takes to be the play’s message could apply to many religions: ‘Let us renounce the world, hate it, and lose it gladly. The only real thing is the soul, with its courage, patience, devotion.’ He adds, however, that this is not ‘the whole spirit of the tragedy’ and, indeed, if pushed further, would ‘destroy the tragedy’ – as do the religious interpretations that imagine Lear and Cordelia reunited in heaven.Footnote 1 Tate’s Lear ends with Cordelia exclaiming ‘Then there are gods, and virtue is their care!’ and Edgar, addressing her, states the moral:

Shakespeare’s ending could hardly be more different. Most notoriously, Kent says, ‘the gods reward your kindness’ (3.6.5) to Gloucester who, some 100 lines later, is tortured and blinded for his actions; Albany’s ‘The gods defend her’ (5.3.230), when he hears that Edmond has ordered the deaths of Lear and Cordelia, is immediately followed by Lear’s entrance with her dead body.Footnote 2 In his RSC production in 2007, Trevor Nunn underlined the irony by giving the play a Christian setting. Everyone on stage knelt in prayer after Albany’s line, and Lear’s entry demonstrated ‘the impotent misguidedness of religious faith’.Footnote 3

The Absurd

In a famous essay published in 1930, G. Wilson Knight described examples in Lear of what he called the ‘Comedy of the Grotesque’, calling Cordelia’s death ‘the final grotesque horror in the play’.Footnote 4 His interpretation was a precursor to the Theatre of the Absurd, of which Samuel Beckett’s plays are the most famous examples. It assumes that the absence of a divine creator means the absence of any meaning in life, and thus in the play itself. In 1962, Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary was published, with a chapter on ‘King Lear and Endgame’. There is some doubt as to whether, as is often said, Kott’s book influenced Peter Brook’s 1962 production of King Lear, but Beckett was a constant influence. In 4.5, Lear and Gloucester looked like the tramps in Waiting for Godot. Brook saw Shakespeare, like Beckett, as depicting an ‘absurd’ universe, frustrating the desire of its characters – especially Edgar and Albany – to impose a moral explanation on events. Brook’s production, seen on tour as well as in Stratford and London, was enormously influential. Charles Marowitz, who kept and published a diary of the rehearsal period, shows a constant desire to make the audience as uncomfortable as possible. It was his idea that the play should end with a faint rumble of thunder, threatening another storm, to counter what he called ‘the threat of a reassuring catharsis’.Footnote 5 A generation later, some critics reacted against the production’s bleakness (the film was bleaker still) and pointed out that this was the result of cuts to any mitigating elements, such as Edmond’s attempt to save Lear and Cordelia. Others argued that a totally pessimistic interpretation has the same effect as the religious one that it rejects, since it makes positive action seem meaningless; the ‘barren dream’ that Keats feared is perhaps what Kiernan Ryan calls ‘the complacent conclusion that this is how things were meant to be’.Footnote 1

13 ‘Hark in thine ear’: Lear (Paul Scofield) with Gloucester (Alan Webb) and Edgar (Brian Murray). Royal Shakespeare Company 1962, directed by Peter Brook. Folger Shakespeare Library 267931.

Political/Historical Readings

Francis Gentleman’s comment, in 1774, on the ‘Poor naked wretches’ speech – ‘We could wish this speech read to certain great folks, every day!’ (Bell’s Shakespeare, p. 43n.) – shows that Lear’s sudden awareness of social injustice was already, at the beginning of an era of revolutions, achieving something of its present importance. When Macready played Lear, it was noticed that he always emphasized ‘those noble passages in which the poet contrasts the lots of rich and poor, of oppressor and thrall’.Footnote 2 This claim is borne out in the actor’s diary entry for 18 Feb. 1839: ‘Acted King Lear well. The Queen was present, and I pointed at her the beautiful lines: “Poor naked wretches!”’Footnote 3 The speech, A. C. Bradley wrote in 1904, is ‘one of those passages which make one worship Shakespeare’.Footnote 4 Bill Clinton, then a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, saw the play at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1968. According to a fellow-student, he was ‘struck that Lear had been on the throne for decades before he learned the first thing about how his subjects lived’ and talked about the play all the way back on the bus, ‘relating it to his life’ and his career plans.Footnote 1

Unlike Lear’s knights, the poor and homeless are not included in the cast of Lear, but vast numbers of them appear in the films of Lear by Brook and Grigori Kozintsev and they have been brought on stage in recent productions: at the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre in 2012, they occupied more and more of the space as the play went on, and at Canada’s Stratford in 1981 and the RSC in 2016 beggars hovered outside Albany’s castle, a reminder of the suffering outside the subjective world of Lear. Nancy Meckler’s Globe production in 2017 opened with a group of homeless people breaking into a theatre apparently under wraps and off limits to them. In the course of the performance, the theatre space gradually lost its ugly wrappings and became itself again, while the actors confronted ‘the thing itself’.

14 Is man no more than this?’ Lear (Kevin McNally), and ‘Poor Tom’ (Joshua James). Shakespeare’s Globe, 2017, directed by Nancy Meckler

Jonathan Dollimore insists, in an often-quoted comment, that empathy is not enough: ‘where a king has to share the sufferings of his subjects in order to “care”, the majority will remain poor, naked, and wretched’.Footnote 1 The political readings of King Lear exemplified by Annabel Patterson, Alan Sinfield, Jonathan Dollimore, and Kiernan Ryan, among others, reject any notion that suffering makes the sufferer a better person and insist that the injustices the play depicts can be changed only by a change in society.

Feminism

Feminist criticism of Lear initially focused mainly on the play’s treatment of Gonerill and Regan, and on Lear’s misogynistic rages, sometimes taking in the implications of Albany’s ‘Proper deformity shows not in the fiend / So horrid as in woman’ (4.2.37–8), which is echoed in A. C. Bradley’s statement that Edmond is the ‘least detestable’ of the play’s three villains because he ‘is at any rate not a woman’.Footnote 2 The contrast between the male and female villains is telling: Edmond addresses the audience eloquently and even wittily; he is chivalric in his fight with Edgar, recognizes the (perhaps dubious) justice of his fate, and tries to undo his most evil action. The two women die off stage – ‘desperately’, as Kent says – without any final moment of insight. Attempts to justify them sometimes emphasize the pain that might lie behind Gonerill’s ‘He always loved our sister most’ (1.1.281–2), and sometimes even demonize Cordelia.Footnote 3 As noted above, most productions now treat them as complex characters and find sympathy for Gonerill, if not for Regan.

Some feminist critics also agree with Janet Adelman’s psychoanalytic reading of the scene where Lear is reunited with Cordelia. Lear seems unable to think of his daughter as the wife of the King of France, but, Adelman argues, it is not only Lear but also Shakespeare who fails to respect her identity as a grown woman, turning her instead into ‘the Cordelia of Lear’s fantasy’.Footnote 4 Few productions, however, have taken an ironic look at a relationship which is responsible for the emotional highpoints of the play, and Kathleen McLuskie and Ann Thompson have questioned whether a feminist response to Lear requires a sacrifice of the theatrical pleasure of empathy.Footnote 1

Ecocriticism