Introduction

Influential work by David Gaimster (Reference Gaimster2005; Reference Gaimster2014) has recently brought the role of material culture in the articulation of maritime identities in medieval Europe into focus. Studying the use of ceramics in Hanseatic towns, Gaimster has argued for the existence of a Hanseatic cultural package, including German stoneware and redware pottery, through which a distinctive cultural identity was expressed around the Baltic coastal zone (Figure 1). One could criticize Gaimster for not paying sufficient attention to the relationship between material culture and identity. The use of concepts such as ‘type fossils’ (Gaimster, Reference Gaimster2014: 65) is suggestive of a quasi culture-historical approach in which objects stand for identities, but his discussion of the movement of ideas alongside objects shifts the debate towards artefacts acting as mediators in the negotiation of identity. Examples might be the emergence of a competitive merchant class, or the cultural tensions identified in Novgorod between the ceramic culture of the Hanse and the wood culture of the local population (Gaimster, Reference Gaimster2005: 418–19; Reference Gaimster2014: 74–75). Therefore, within Gaimster's discussion, the extent to which objects carry or mediate identity is ambiguous.

Figure 1. Map showing location of places and regions mentioned in the text and some major ports. The rectangle marks the study area in south-east England. 1: London, 2: Bruges, 3: Hamburg, 4: Lubeck, 5: Danzig, 6: Riga, 7: Novgorod, 8: Bergen, 9: Kalmar, 10: Saintes (the production region for Saintonge pottery); 11: Bordeaux, 12: Southampton, 13: Meuse Valley, 14: Rouen, 15: Scarborough.

Background Image: WikiCommons reproduced under a Creative Commons by Attribution/Share-Alike Licence.

Gaimster's work has stimulated further research in this area. Naum (Reference Naum2013; Reference Naum2014) draws upon post-colonial approaches to explore how ‘Hanseatic’ objects were mediators in the social confrontations experienced in Baltic ports (see also Immonen (Reference Immonen2007) for a similar approach). For Naum, objects are one of a range of actors in the negotiation of distinctive port experiences, with novel objects becoming meaningful in new ways as they become integrated into everyday life (Naum, Reference Naum2014: 673). Naum also stresses how for merchants, people with ‘dual lives’ in their port of origin and the places in which they spend considerable amounts of time on business, objects play an important role in creating a sense of homeliness and familiarity, providing ‘a recognizable backdrop for their lives disrupted by migration’ (Naum, Reference Naum2013: 386). The concept of the ‘cultural package’ is further critiqued by Mehler (Reference Mehler2009), who argues that objects found different meanings within the context of the North Atlantic islands. Mehler's study emphasizes the role of the life histories of objects, as things become meaningful as they are entangled in new courses of social interaction. These studies do not show Gaimster's consideration of Hanseatic material culture to be wrong, but emphasize that his interpretation is specific to the Baltic towns. These discussions highlight a need to address the contextual subtleties in how objects became meaningful and how, in doing so, they also mediate the emergence and re-iteration of various identities.

Whilst recent research has focused on the Hanse, this work can be fruitfully used to stimulate discussions of the role of material culture in medieval ports more generally; the focus here is on the twelfth–fourteenth–century Channel ports of south-eastern England and their relationship with their hinterland.

Ports can be characterized as zones of confrontation. Post-colonial approaches demonstrate frontiers to develop specific characters through the collision of traditions, ideas, and worldviews (Naum, Reference Naum2010: 106). The specific entanglements between people, goods, and ideas which come about in ports might be seen as leading to the emergence of particular forms of identity and material worlds. The ‘in-betweenness’ of these places sets them apart from other towns, and played an important role in determining the trajectories along which their character developed. The distinctiveness of ports and coastal communities is well demonstrated through other studies. For the early medieval period in the English Channel and North Sea areas, Loveluck and Tys (Reference Loveluck and Tys2006) argue that interactions between coastal communities and the use of imported goods led to the emergence of distinctive forms of maritime community and social identity (an idea further developed by Davies, Reference Davies2010; see Jervis, Reference Jervis, Williamsen and Kik2016a, in relation to the early medieval period). Sindbæk (Reference Sindbæk and Knappett2013) uses network analysis to explore these early medieval maritime relationships further, identifying multi-scalar zones of interaction through the examination of artefact distributions. Material culture was also implicated in social relationships within ports. In Southampton, for example, imported pottery has been argued to have developed distinctive meanings and become enrolled in identity formation (Brown, Reference Brown, Blinkhorn and Cumberpatch1997; Jervis, Reference Jervis2008). Working at a different scale, Pieters and Verhaege (Reference Pieters and Verhaege2008) show that a later medieval Flemish fishing community encountered Mediterranean pottery differently from those living in major mercantile ports, meaning that in this context it developed distinctive meanings and was enrolled in the emergence of particular forms of coastal identity. The social role of material culture in ports is an area of great interest across northern Europe. We can only better understand variation in the relationships between people and objects across coastal areas through the development of interpretive frameworks and the use of a greater variety of case studies. This contribution seeks to address how pottery mediated distinctive experiences in ports and how it was enrolled in the emergence of coastal communities. This requires a move beyond discussions of imports as components of ‘cultural packages’, to focus on the mediatory role of objects within social interaction.

Harris (Reference Harris2014) has considered the concept of community within archaeology. Drawing on insights from ‘assemblage theory’ (inspired in particular by Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987; DeLanda, Reference DeLanda2006; Bennett, Reference Bennett2010) he calls for our ideas of community to extend beyond the human, to see communities as beginning ‘with relationships amongst humans, animals, plants and material things’ (Harris, Reference Harris2014: 89). Harris's concept of the community stresses that the relationships through which communities emerge and persist need not be spatially situated (a view paralleled in Naum's Reference Naum2013 discussion of the German diaspora in Kalmar) and that communities might overlap and occur at multiple scales. People may have, for example, felt joined at one level to others through their use of stoneware pottery but, simultaneously, this connection could be fragmented through how they related to this pottery at a personal level. For Harris, and other archaeologists taking similar relational approaches (e.g. Lucas, Reference Lucas2012; Fowler, Reference Fowler2013; Jervis, Reference Jervis2014), identities are not transported by objects. Rather, ‘persons’ emerge through interactions between the human and non-human. Following Latour (Reference Latour2005: 27), groups (or communities) emerge and are sustained through interactions. Study must focus not on classifying identities but, rather, on studying the social relationships through which the emergence of ‘persons’ and ‘communities’ was distributed across the material world.

In essence such approaches see objects and people as becoming meaningful together, requiring us not only to focus on how identities and communities emerge from relationships, but also to rethink our approaches to objects. Van Oyen (Reference Van Oyen2013) uses post-colonialism as a metaphor for addressing this problem, arguing that archaeological classification creates a priori assumptions about the social significance of particular objects, masking the processes through which objects found meaning. Classification systems create an ‘in-betweenness’ as types with similar characteristics are contrasted as ‘others’. In order to overcome this, Van Oyen (Reference Van Oyen2013: 96) calls for a focus on tracing object biographies and trajectories in order to understand how the presence of different things led to different constellations, or assemblages, of people, things, and ideas emerging (see also Kopytoff, Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986; Gosden & Marshall, Reference Gosden and Marshall1999). As demonstrated by Fowler (Reference Fowler2013: 44–46), ‘black-boxes’ (defined (after Latour, Reference Latour2005) as reified concepts which circulate through discourse) such as the ‘Hanseatic cultural package’ or even ‘imported medieval pottery’ must be unpacked to understand the processes through which they emerged. Our interest shifts from distribution patterns of ‘known types’ to the cultural and economic patterns which underlie them (Sindbæk, Reference Sindbæk and Knappett2013: 80). Whilst observing a phenomenon in the archaeological record is useful as a means of identifying similarity and difference, or cultural contact, at one level, it is only through understanding the social interactions which led to these phenomena that we can move towards a deeper understanding of past social dynamics—the vibrancy of past, more-than-human, communities (Harris, Reference Harris2014: 90–92).

Case Study: Ceramics and the Channel Ports

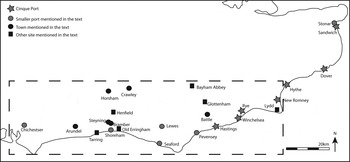

Ports are not a homogeneous class of settlement; they, like the communities described above, are constituted of social relationships. It is these relationships which make them distinctive from other settlements and from each other. A fundamental element of the character of a port community is the flows of goods which are traded through a particular place and, in particular, those items which are used by port households. At a basic level the ports of south-eastern England can be viewed hierarchically. All the ports discussed here operated below the major ports of London and Southampton, the most important being the Cinque Ports. These were the principal Channel ports which, in exchange for naval service, were given freedom and trading privileges. They were major participants in the Gascon wine trade and had privileges in regard to the North Sea herring industry (Sylvester, Reference Sylvester, Martin and Martin2004: 15). The Cinque Ports are situated on the coast of Kent and Sussex, from Faversham in the east to Seaford in the west (Figure 2). Not all the ports have been subject to excavation, the most intensively investigated being Dover (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Corke and Cotter2006), New Romney (Draper & Meddens, Reference Draper and Meddens2009), Rye (Dawkes & Briscoe, Reference Dawkes and Briscoe2012; Margetts & Williamson, Reference Margetts and Williamson2014), New Winchelsea (Martin & Rudling, Reference Martin and Rudling2004), and Hastings (Rudling, Reference Rudling1976; Devenish, Reference Devenish1979; Rudling & Barber, Reference Rudling and Barber1993), as well as the ‘limbs’ (smaller ports under the control of the Cinque Ports) of Seaford (Freke, Reference Freke1979a; Gardiner, Reference Gardiner1995; Stevens, Reference Stevens2004) and Pevensey (Dulley, Reference Dulley1966; Reference Dulley1967; Barber, Reference Barber1999). These limbs can be seen as occupying a second tier in the hierarchy alongside other towns such as Shoreham (Thomas, Reference Thomas2005; Stevens, Reference Stevens2011) and Lewes (Page, Reference Page1973; Freke, Reference Freke1975; Reference Freke1978; Drewett, Reference Drewett1992). These were important regional towns with varying degrees of administrative control over their hinterlands. Chichester occupies a slightly ambiguous position within this hierarchy. An important exporter of wool, this large regional town was not a Cinque Port, but was larger than other Sussex port towns. The final tier is occupied by smaller landing places. These are coastal villages where communities were likely to have been involved in small-scale fishing and trading alongside agriculture. Examples are Tarring (Barton, Reference Barton1964), a village with a palace belonging to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lydd (Barber & Priestly-Bell, Reference Barber and Priestly-Bell2008).

Figure 2. Map indicating the extent of the study area and the location of sites mentioned in the text.

Archaeological excavations in these towns have generally been small in scale, being undertaken in response to development pressure. For this reason this study focuses only on the stretch of coastline from New Romney in the east to Chichester in the west, but will make reference to material from excavations in the Cinque Ports of Dover and Stonar. It is not necessary here to discuss in detail the archaeology of each town, but rather to draw out some general points. In all cases excavations have targeted house plots and have produced a wide range of local and imported pottery, as well as, in many cases, equipment associated with fishing. In Lewes, an inland port and county town, excavations have revealed evidence of craft production (Page, Reference Page1973). Such evidence is largely missing from the other ports, probably due to the nature of the investigations rather than a lack of craftsmen; indeed craftsmen are known from Rye, for example, from historical records (Draper, Reference Draper2009: 66–69). Rye is also known for its major pottery industry, which produced highly decorated wares distributed across south-eastern Sussex and south-western Kent (Barton, Reference Barton1979: 191–222). Archaeology provides evidence for changes in the topography of the towns and household economies, but historical records provide the best source for understanding the towns in more general terms.

The Cinque Ports largely have Saxo-Norman origins, and they are likely to have developed from existing landing places (see Gardiner, Reference Gardiner1999). New Romney, for example, grew from a fishing village (Draper & Meddens, Reference Draper and Meddens2009: 14), whilst Rye, Hastings, and Dover were all established ports by the eleventh century (Draper, Reference Draper2009: 2–6). Pevensey, Chichester, and Lewes were also already established settlements at this time, but Seaford and Shoreham were both new foundations around the turn of the thirteenth century. New Winchelsea was founded in 1288 to replace an earlier port lost to the sea. Here, plots of varying sizes relate to differences in the wealth and status of inhabitants. The town had a defensive circuit and stone-built houses with undercrofts used for the storage and sale of goods, particularly wine (Martin & Martin, Reference Martin and Martin2004). The Cinque Ports were exempted from certain forms of taxation, and therefore the usual range of sources for understanding urban populations are not available. The mercantile communities were clearly cosmopolitan, given the role of foreign shipping.

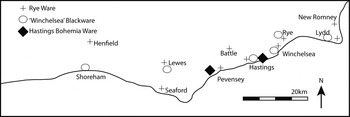

The ports had varying trading relationships, principally with northern France and Flanders. Wool export was of particular importance to Shoreham and Seaford, on the south side of the chalk downland, an area specializing in sheep husbandry (Pelham, Reference Pelham1933). Winchelsea and Rye, surrounded by the clay Weald, exported goods such as timber and iron, as well as regional goods shipped along the coast to these major ports. Such coastwise contact is attested to both by ceramic evidence, with products from coastal production sites (at Hastings, Rye, and near Winchelsea) being distributed along the coast (Figure 3) and by the distribution of slate roofing materials imported from south-western England (Holden, Reference Holden1965). Analysis of port records highlights the importance of foreign shipping to the timber trade to northern France and Flanders from the Cinque Ports (Pelham, Reference Pelham1928: 175). In relation to wool, a contrast exists between the Cinque Ports, where export was chiefly undertaken by foreign ships, and Seaford and Shoreham, where English shipping was more important (Pelham, Reference Pelham1933: 133; Sylvester, Reference Sylvester, Martin and Martin2004: 11). Salt was a further export from Pevensey and Shoreham, often by foreign ships, although environmental change caused this industry to decline during the fourteenth century (Pelham, Reference Pelham1930: 183; Dulley, Reference Dulley1966: 42; Holden & Hudson, Reference Holden and Hudson1981). A wide range of ships imported goods into the Cinque Ports. In the late thirteenth century, for example, shipping came from Spain, northern France, and a number of English ports (Sylvester, Reference Sylvester, Martin and Martin2004: 9). Amongst the imported goods were fish and cloth (Pelham, Reference Pelham1930: 180; Sylvester, Reference Sylvester, Martin and Martin2004: 17). Ships from the Cinque Ports were also important components of fleets importing Gascon wine, with Winchelsea contributing the highest number (Sylvester, Reference Sylvester, Martin and Martin2004: 13; Draper, Reference Draper2009: 27–28).

Figure 3. Distribution of wares produced in or close to coastal towns in England.

It is clear from the documentary evidence that these ports operated in a variety of trading networks, in which both English and Continental merchants and sailors participated. The pottery discussed here was not a commodity traded in bulk (indeed in medieval England it is probably only German stonewares that were traded in this manner; see Gaimster, Reference Gaimster1997); it is absent from historical records and imported ceramics are only present from archaeological contexts in small quantities. However, by following the flows of ceramics into these ports, we can begin to relate pottery to these maritime networks and better understand how objects mediated the emergence and re-iteration of maritime communities in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, rather than limit our investigations to the mapping of the movement of goods.

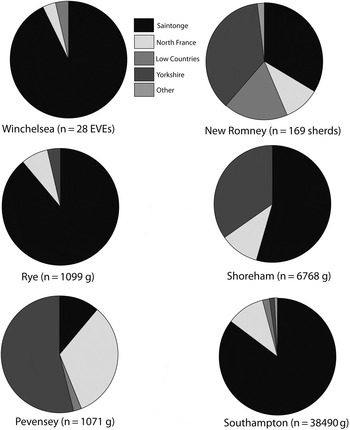

Flows of Pottery

The pottery imported into Kent and Sussex has been reviewed in studies by Hurst (Reference Hurst1981) and Brown (Reference Brown, Bocquet-Liénard and Fajal2011). Hurst (Reference Hurst1981: 121) identified an increase in imports of Saintonge pottery from Gascony into Sussex through the thirteenth century and questioned the extent to which this pottery was directly imported or re-distributed through head ports. Hurst (Reference Hurst1981: 121–22) also highlighted that the bulk of imported pottery was from northern France (specifically Normandy), with only small quantities from the Low Countries and Germany (Figure 4). Brown's (Reference Brown, Bocquet-Liénard and Fajal2011) study benefits from thirty years of rescue excavations in port towns. Brown summarizes the pottery present in a number of ports along the coast and demonstrates the potential of this imported material for further interpretation.

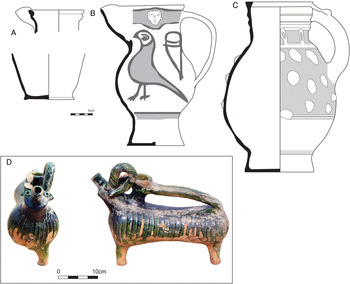

Figure 4. Examples of imported pottery types discussed. A: Saintonge whiteware from excavations in Winchelsea (redrawn by the author from Martin & Rudling, Reference Martin and Rudling2004); B: Saintonge polychrome ware from Glottenham (redrawn by the author from Martin, Reference Martin1989); C: Rouen-type ware from Pevensey (redrawn by the author from Dulley, Reference Dulley1967); D: Scarborough ware aquamanile from Shoreham.

©Archaeology South East 2004. Reproduced by permission of Archaeology South East. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

If we are to understand how pottery became meaningful in the emergence of identities and through its connections with different material worlds, we need to focus not on the composition of the assemblages themselves but rather on the processes through which these assemblages emerged. Assemblage is taken here in a dual sense: firstly in the sense of a group of material from an archaeological site; and secondly in the sense discussed above, as a collection of people and things, of which pottery was one component. To understand these processes, we need to focus on the flows of pottery coming into and through the ports. Closely related to conventional ideas of artefact biography, the tracing of flows allows us to consider how objects might follow multiple trajectories, through which they become entangled with people and things. It is from these entanglements that multiple meanings, communities, and identities emerge in relation to each other (Van Oyen, Reference Van Oyen2013; Harris, Reference Harris2014). In what follows, pottery from different sources is discussed, before some themes are elaborated on in more general terms. It should be noted that types are used here as a convenient shorthand to indicate source, rather than implying that a particular typology is being imposed onto the material. Pottery types can be considered to be ‘black-boxes’ which have emerged from the classification of pottery in relation to where and how it was produced, which have become solidified as they have circulated in the literature. However, this categorization masks the social processes in which these objects were framed, understood, and operated (Fowler, Reference Fowler2013: 44–46; Van Oyen, Reference Van Oyen2013).

Before entering into discussion it is necessary to briefly mention the methodology used. The data discussed here are gathered from published and unpublished reports produced since the 1970s. The methods of quantification used by pottery researchers in the region are highly variable. Whilst modern reports typically quantify the material by sherd count and sherd weight (MPRG, 2001), older reports often use only sherd count or vessel count. In one case (Winchelsea) only Estimated Vessel Equivalent (EVE), a statistical measure of the number of vessels present rather than an absolute quantity, was published (Martin & Rudling, Reference Martin and Rudling2004). Therefore, in some cases it is only possible to refer to find-spots, particularly where only interim reports are available (for example for Stonar and recently excavated sites in Lewes). Where possible, sherd weight is the preferred quantification measure, as this is not biased by breakage patterns, which have an impact on the number of sherds present in an assemblage (see Poulain, Reference Poulain2013). Where sherd weight is not available, vessel count has been used in preference to sherd count where figures are published. The impact of the inconsistencies in quantification is minimized by the small quantities under consideration and the questions being asked of the material. It is not intended here to compare the compositions of assemblages in detail (which would require consistent quantification) but instead to consider where vessels are being consumed and approximately in what quantity. As in most cases where imported pottery is comparatively rare, it is the presence of types which is of particular significance. Therefore, whilst these inconsistencies limit the scope of the discussion, they do not prevent a detailed consideration of the movement of pottery around the study region.

Saintonge Pottery

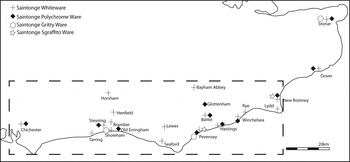

The most widespread pottery is that from the Saintonge region of south-western France (Barton, Reference Barton1963). The wares present include green-glazed whitewares (Figure 4a), polychrome wares (Figure 4b), gritty-ware mortars, and sgraffito wares. These vessels are generally assumed to relate to the import of Gascon wine. This is supported by the evidence here. Saintonge wares account for the highest proportions of the imported pottery from any particular source from the Cinque Ports of New Romney (34 per cent of imports by sherd count, n = 169 sherds), Winchelsea (93 per cent of imports by EVE, n = 28 EVEs) and Rye (89 per cent of imports by sherd weight, n = 1.1 kg) and are also present in unquantified assemblages from Hastings (Rudling & Barber, Reference Rudling and Barber1993) and Stonar (MacPherson-Grant, Reference MacPherson-Grant1990) (Figure 5). It is these assemblages which also have the highest diversity of Saintonge products. Polychrome wares are present in all the ports, but sgrafitto products are present only in New Romney and Pevensey. Gritty mortars occur in Stonar and Winchelsea (Figure 6). Saintonge gritty and whitewares are also present in Shoreham (where they account for 55 per cent of imports by sherd weight, n = 6.8 kg; Stevens, Reference Stevens2011), a port which was involved in the direct importation of Gascon wine but less intensively than the Cinque Ports. The evidence suggests that the Gascon wine trade was the route through which these vessels entered the ports and the quantities present suggest that the green-glazed and polychrome jugs, at least, were widely marketed and used in these towns. The profile of the Cinque Ports assemblages is quite similar to that of Southampton, another port importing wine under royal patronage (Brown, Reference Brown2002: fig. 3).

Figure 5. Composition of the imported pottery assemblages from the sites under discussion (data: Barber, Reference Barber1999; Brown, Reference Brown2002; Martin & Rudling, Reference Martin and Rudling2004; Draper & Meddens, Reference Draper and Meddens2009; Stevens, Reference Stevens2011; Dawkes & Briscoe, Reference Dawkes and Briscoe2012; Margetts & Williamson, Reference Margetts and Williamson2014).

Figure 6. Distribution of Saintonge products in the study area.

In Dover some spatial differences can tentatively be seen in the distribution of Saintonge products. Three polychrome jugs were excavated from a garderobe in the core of the town (Rix & Dunning, Reference Rix and Dunning1955) but at Townwall Street, a site believed to be marginal and occupied by fishermen, Saintonge products are rare (4 per cent of the total 2.3 kg of imported pottery by weight) when compared with the range of other French and Low Countries imports present (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Corke and Cotter2006). It is possible that the circumstances of excavation in Dover provide some evidence of different consumption patterns and the significance of these needs to be tested when further excavations are undertaken in the other Cinque Ports. In Rye these vessels, as well as other imported types, apparently influenced local pottery production with the thirteenth and fourteenth century production centre adopting decorative motifs and formal elements (such as the distinctive Saintonge ‘parrot-beak’ spout) from the imported wares which were present in the town (Barton, Reference Barton1979: 221).

Saintonge pottery is often seen as reflecting a wine drinking ‘cultural package’, with these products being perceived as ‘appropriate’ for wine consumption. However, the widespread use of this pottery amongst coastal communities suggests that the association with wine may be less important than the availability of the pottery and its aesthetic qualities, with the decoration potentially finding different meanings depending on the context of use (Allan, Reference Allan1984; Courtney, Reference Courtney1997; Jervis, Reference Jervis, Sibbesson, Jervis and Coxon2016b). Three main types of sites received Saintonge products, presumably re-distributed from these principal ports (Figure 6). The first are coastal sites. Green-glazed and polychrome wares have been recovered from Chichester, Pevensey, Lewes, and from the market town of Steyning, situated on the navigable River Adur (Freke, Reference Freke1979b; Barton, Reference Barton1986; Evans, Reference Evans1986). Saintonge whiteware has been excavated from Seaford, Bramber (a small town close to Shoreham), and the smaller coastal settlements at Lydd and Tarring (Barton, Reference Barton1964; Barber and Priestly-Bell, Reference Barber and Priestly-Bell2008). The second type of site are towns, with a handful of Saintonge whiteware sherds found in the inland towns of Horsham (one sherd from an assemblage of 451 medieval sherds; Stevens, Reference Stevens2012) and Battle (six sherds from an assemblage of 1422 sherds; James, Reference James2008). The third kind of sites consists of inland manor houses and institutions. Whiteware has been excavated at Bayham Abbey (Hurst, Reference Hurst1981) and from a moated manor house at Henfield (Funnell, Reference Funnell2009), whilst polychrome ware has been recovered from the moated site at Glottenham in the Weald (Martin, Reference Martin1989). In these cases the assemblages are not quantified; only a few sherds are present, suggesting that vessels were re-distributed from the Cinque Ports, although the Chichester examples may have been acquired from Southampton.

This wide coastal distribution across a range of sites is suggestive of a coastal network of interaction, perhaps mediated principally by the transport of fish to and from the Cinque Ports. It is likely that these products, along with other commodities, were acquired in these cosmopolitan markets. The flow of Saintonge products into the Cinque Ports can be considered to be highly commercialized, being associated with the lucrative wine trade. Its use in the Cinque Ports created distinctive material worlds, possibly associated with communal wine drinking and the negotiation of mercantile communities and identities through hospitality. Merchant communities formed as people engaged in particular social practices. Saintonge pottery played a part in the re-iteration of the communities of practice, through which merchants came to be defined as distinctive ‘persons’. It is overly simplistic to see the presence of smaller quantities of these products in other ports and coastal settlements as the exportation or expansion of this mercantile culture. For some living and working in the smaller ports, wine drinking and the use of Saintonge products may have been aspirational. However, we can also view the Saintonge products as forming part of a more general coastal material world, acting to join coastal communities, from merchant to fisherman. Van Oyen (Reference Van Oyen2015) likens the role of towns in the Roman economy to railway points, places in which the trajectories of things might be sent off in a variety of different directions. If we view objects and people as following trajectories, or ‘lines of becoming’ (following Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987), we can see the markets in the Cinque Ports as fulfilling a similar role. Saintonge pottery flowed into the markets as commodities, but as they passed through the market their role was transformed.

Objects can be perceived as having affordances (Knappett, Reference Knappett2005: 52); what an object can do is relational, emerging with specific contexts as they were confronted by other objects enrolled into multiple forms of domestic assemblages of goods. In the merchant house they were linked to other exotic goods and foodstuffs and became involved in the negotiation of mercantile culture (see also Mellor, Reference Mellor2004). Within such houses hospitality was important for negotiating business deals and credit. Jugs such as those from the Saintonge afforded commensal drinking, an activity which joined wine, pottery, merchants, and domestic spaces in the emergence and re-iteration of mercantile communities. In places like Lydd these items were not symbols of wealth or port culture, but part of a more meagre material world, the product of a distinctive set of maritime engagements which resulted in a distinctively coastal relationship with an emerging material culture. In the context of a small fishing household these objects were enrolled in different sets of social relationships, and came to afford different forms of social interaction. Here they perhaps acted as mediators between coastal communities living in ports and smaller settlements. It should be noted that other goods, such as Rye pottery and West Country slate, have a similar coastal and riverine distribution (Figure 3), indicating that coastal contact created networks of exchange which became manifest as material signatures at one interpretive level, but as overlapping and interconnected processes at another; in other words they were sets of social and economic relationships through which coastal life became distinctive.

A consideration of the inland use of Saintonge pottery adds a further layer of complexity. The vessels presented in Horsham are probably a by-product of the export of Wealden resources through Shoreham. In contrast, the pottery from manor houses and from the town of Battle, a settlement on the estate of a major religious house (Battle Abbey), perhaps reflects status related to trade contacts. Dyer (Reference Dyer1989) highlights that major households and institutions often used larger regional markets to acquire produce in bulk and at favourable rates. Battle Abbey dealt directly with the Cinque Ports for its fish supply and fish was sold in the town's market. The supply of imported pottery to the castles at Pevensey (unquantified, but consisting of Rouen-type, Saintonge, and Low Countries highly decorated wares), Bramber (twenty-one sherds of northern French whiteware from a total of 4842 sherds), and Lewes (less than 1 per cent of the pottery by weight; all from northern France or the Saintonge), as well as to Lewes Friary (not quantified, but consisting of Saintonge whiteware and glazed ware from northern France) is less easy to interpret. Imports are present in small quantities at all of these sites, but there is no clear difference between the types present on these sites and in the associated towns, making it difficult to determine whether they were acquired locally or through regional markets (Barton, Reference Barton1977; Drewett, Reference Drewett1992; Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Gregory and Russell1996; Lyne, Reference Lyne2009).

The de Etchingham family, who held Glottenham manor, also dealt directly with Cinque Port merchants and had interests in Winchelsea (Saul, Reference Saul1986: 178). Pottery was probably not a major commodity in these exchanges, but these commercial relationships opened up a channel along which Saintonge pottery could flow, introducing it to a situation where it was potentially implicated in the negotiation of domestic hierarchy and became a symbol of status. The heraldic imagery found on the Saintonge polychrome pottery may have appealed to a knightly family such as the de Etchinghams and within the formalized dining contexts of larger provincial households these serving vessels were probably enrolled in the re-iteration of hierarchical relationships (see Jervis, Reference Jervis2014; Reference Jervis, Sibbesson, Jervis and Coxon2016b). Whether this was the case or not, these wares were not a ‘cultural signature’ of mercantile life, but rather objects which linked major households, be they knightly or religious, with the Cinque Port markets and mediated the negotiation of meaning and identity in these hierarchically ordered households differently than they did in the commensal drinking environment of the mercantile port (see Saul, Reference Saul1986: 186 on the relationship between knightly families and urban life). Similarly, vessels were not acquired as high-status objects, but acquired this association as they flowed through ports into these hierarchically charged contexts.

North French and Low Countries Pottery

Pottery from northern France includes plain Normandy gritty wares (typically present in the form of pitchers and jars), highly decorated jugs produced in the Rouen area (Figure 4c), and other glazed whitewares of less certain attribution. Also within this group are highly decorated Low Countries redware jugs, considered by Gaimster to form part of the Hanseatic package, plainer Flemish greywares, Meuse-valley glazed wares, and red-painted wares from northern France. A final, unusual, type is the so-called céramique onctueuse, a distinctive type of coarseware pottery from Brittany.

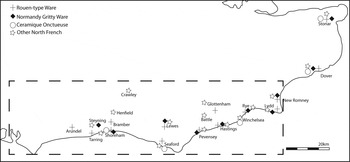

Although diverse in source and type, some general trends emerge in the distribution of these wares, which is overwhelmingly coastal and riverine (Figure 7). Rouen-type ware, for example, has been recovered from a number of towns, including Hastings, Lewes, New Romney, and Pevensey, as well as from the manorial site at Old Erringham (Holden, Reference Holden1981) and the smaller coastal settlements at Lydd and Tarring. The distribution of the plainer Normandy gritty wares is similarly coastal. The less distinctive northern French products have a wider distribution. Examples from Crawley (Stevens, Reference Stevens1997) may have arrived via London or the south coast ports, but sherds have also been recovered from Chichester, Battle, and Glottenham. The Low Countries products are only present in small quantities, occurring in large and small ports. Céramique onctueuse is present in very small quantities and has been recovered from the Cinque Ports of Dover (Hodges, Reference Hodges1978), Stonar, and Winchelsea as well as from Seaford. The ware is also known from Southampton (Brown, Reference Brown2002: 25). The link between this type and the Cinque Ports perhaps indicates that this ware was a by-product of the Gascon wine trade, possibly acquired for use on the ships to replace broken pottery vessels.

Figure 7. Distribution of northern French products in the study area.

Unsurprisingly the range of sources represented relates to the trading contacts of the ports in northern France, Flanders, and the Netherlands. The quantities of imported wares are small in most assemblages and even in the Cinque Ports these wares account for a small part of the imported pottery. The evidence does not suggest a well-established ceramic trade, but rather the occasional acquisition of imported vessels as a by-product of more lucrative trade. The evidence from Townwall Street in Dover supports this interpretation. Here, at the margins of a Cinque Port particularly associated with ferrying and fishing, vessels from a range of northern French and Flemish production centres are present, which probably indicate vessels acquired either for use on ships, as souvenirs, or as speculative purchases (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Corke and Cotter2006: 408). Some vessels are likely to have been imported for marketing in the ports themselves and this could provide the mechanism for vessels to reach manorial sites such as Glottenham, mirroring the acquisition of Saintonge pottery in this context. If such a mechanism did exist, it emphasizes the points made by Fowler (Reference Fowler2013) and Van Oyen (Reference Van Oyen2013) about the need to un-package defined archaeological categories. Saintonge pottery and northern French pottery are different types of pottery, produced in different places and exchanged through different mechanisms; however, in the context of the moated site at Glottenham, both types were highly decorated jugs, probably acquired from Winchelsea merchants for serving at the table, possibly because of their iconography which appealed to the knightly household. However, these goods need not have been acquired because they symbolized wealth, but, rather, they came to be status symbols through their use in this context. It would appear that the source of pottery was less important than its aesthetic and functional qualities, with ceramic serving jugs perhaps acting as a medium through which strictly hierarchical serving practices could be enacted. This leads us to an important interpretive and methodological point; that categories of pottery defined on the basis of production traits split apart and flow into each other, as new constellations of objects are established through trade and as new communities, identities, and material meanings emerged through acquisition and use.

The coastal and riverine distribution of these wares highlights the relationship between their acquisition and maritime networks. Whether acquired on the European continent as souvenirs or to replace broken vessels used on boats, or imported as part of a miscellany of products for re-sale in the ports, these vessels can be seen as elements of coastal interactions. They contributed to the emergence of distinctive material worlds which linked coastal households in town and country exhibiting different levels of wealth and status, differentiating them from inland communities. Yet, as with the Saintonge products, they entered into different constellations of objects, contributing to different types of domestic environment, and linking people in a broader maritime community.

Yorkshire Pottery

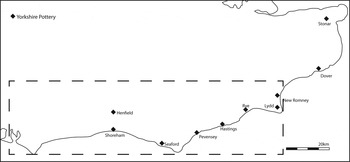

The Cinque Ports’ involvement in the North Sea herring fishery is typically assumed to be the means through which Yorkshire pottery flowed into the south coast ports (Figure 8). It has been recovered from the Cinque Ports and their limbs, and is typically Scarborough ware (see Farmer & Farmer, Reference Farmer and Farmer1982), often occurring in distinctive forms, as aquamaniles (Figure 4d) and knight jugs, not available on the local market. These distinctive vessels may have been acquired by fishermen as souvenirs, or perhaps speculatively for onward exchange. These unusual vessels were obtained through specific networks of interaction and can be seen as mediating the emergence of communities, appearing not only through collective engagement in fishing, but also through distinctive material engagements, which implicated them in a network extending across the North Sea zone.

Figure 8. Distribution of Yorkshire pottery in the study area.

Discussion and Conclusion: Coastal Identities and Community Networks

Just as inland communities were joined through the communal working of fields and the marketing of produce and products in local markets, so the everyday activities of coastal communities linked people and things in networks of interaction. Coastal households were joined in sets of socio-economic relationships from which distinctive, dispersed communities, mediated through the exchange of goods including pottery, emerged. This is particularly clear in relation to Yorkshire pottery, in forms traditionally interpreted as related to high-status consumption, its use seemingly limited to coastal fishing communities in this context. There are clear similarities between the ceramic assemblages from the Cinque Ports, which are distinguished from those from other coastal sites principally by the quantity of imported pottery and the proportion of Saintonge types present. Tracing the flows of imported pottery has revealed that it was entangled in a variety of social relationships and that, rather than standing for a mercantile identity, its use created distinctive material worlds and contributed to the emergence of multi-scalar coastal communities. So far these observations have been limited to a specific case study, but there are elements of the approach taken here which could, if applied to other material, assist with the development of a more nuanced understanding of the social role of material culture.

It is clear that a wide range of people living in coastal areas had access to imported pottery and, rather than standing for high-status associations as is commonly assumed, these objects played a role in the re-iteration of multiple forms of coastal identity (see also Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Corke and Cotter2006: 412). We can therefore see interactions with pottery vessels, at different stages of their biography, as mediating different scales and types of community. Pottery becomes what Bennett (Reference Bennett2010: 42 [after Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987]) terms an ‘assemblage convertor’, something which links assemblages (or, in this instance, communities) being performed in disparate places at different scales. The regional-scale coastal community fragmented into different types of community, mercantile households and fishing villages for example, all of whom interacted with and understood this pottery in different ways, but who were joined through it, for example by interactions in the marketplace.

This multi-scalar relationship between communities, identities, and objects is of central importance when examining coastal interaction across medieval Europe. In studies of the Hanse it becomes particularly apparent in the application of post-colonial approaches (Immomen Reference Immonen2007; Naum, Reference Naum2013; Reference Naum2014); where we see people linked in relationships of confrontation, in which material culture acts as a mediator, and in which different forms of community emerge within port towns. At a different scale this is apparent in the role given to pottery amongst the communities studied by Gaimster (Reference Gaimster2005; Reference Gaimster2014) and Mehler (Reference Mehler2009). At one scale, these communities are linked through common associations with Hanseatic material culture, but they fragment between regions, settlements, and households as multiple forms of community and identity emerge in relation to these objects. Ports are boundary places, gateways where diverse people and things come together to create cosmopolitan communities. As objects pass through them they are sent along varying ‘lines of becoming’, trajectories which send them into diverse sets of entanglements through which they are rendered meaningful, people identify themselves, and places develop distinctive characters.

A focus on interactions (either through formal network analysis or conventional studies of artefact distributions), when interpreted within a framework in which object meanings, identities, forms of personhood, and communities are relational concepts, allows a deeper consideration of the ways in which similar objects might be enrolled in the emergence of different forms of community and identity and moves us away from static cultural packages towards a more dynamic understanding of past identities. The examination of how pottery flowed into and through a number of ports of different type, and consideration of the inland use of this pottery, have demonstrated how people and objects can be considered to be mutually constituted. Such an approach forces us to drop our preconceptions about the status and meaning of imported pottery and focus on understanding the effect of it flowing along varying trajectories and becoming entangled in different forms of social assemblage. In doing so, it has been possible to argue for the presence of multi-scalar coastal communities and for pottery as mediating different forms of personhood, rather than carrying specific identities. In conclusion this study calls for deeper contextual study of imported pottery at multiple scales to gain a fuller understanding of the dynamics of coastal interaction in medieval Europe.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper presented at the EAA conference in Glasgow in 2015 and I am grateful to the audience members who made useful comments. I would also like to thank Archaeology South East for permission to use the photograph of the aquamanile from Shoreham.