Writing about Shostakovich’s incidental scores, Gerard McBurney states that ‘In length and variety they represent a substantial part of his output, yet they are surprisingly little known.’Footnote 1 Similarly, Eric Saylor observes of Vaughan Williams that his ‘dramatic works typically receive the least recognition or respect’.Footnote 2 The observation that incidental music – specifically music performed in theatre productions with spoken text, rather than musical theatre or opera – is among the most unfamiliar of twentieth-century composers’ works is hardly limited to Vaughan Williams and Shostakovich. Although theatre music broadly has received increasing scholarly attention in the last decade, largely thanks to the flourishing interest in melodrama and the continued growth of opera and musical theatre studies, incidental music of the early twentieth century nonetheless remains a little-discussed area in musicology.Footnote 3 Very little is known about the scope of incidental music during this period, the impact that it had in performance, how this music was understood in its time, or how its composers contributed to theatrical culture.

Composers’ incidental scores can be approached with a view towards understanding a composer’s ‘aesthetic sympathies’,Footnote 4 and this has been done extremely successfully by authors including Eija Kurki, Jeffrey Kallberg and Daniel M. Grimley.Footnote 5 However, many of the reasons for incidental music’s historical neglect arise from musicology’s entrenched composer-focused, work-centric perspective. Incidental music fulfils very few of the criteria associated with the musical ‘work’ and will inevitably come out wanting when judged by aesthetic and analytical criteria devised within a framework that ascribes value to genres according to how self-sufficient the music is. Additionally, a sustained emphasis on how incidental music fits into a composer’s broader oeuvre sidelines other important questions, such as how spectators experienced the music in performance, how the music interacted with other elements of the sound design (or indeed visuals), or how the production’s reception might prompt a reassessment of how the composer was viewed in their own lifetime.

This article argues that fully accounting for incidental music’s function and impact in the early twentieth century necessitates changing the object of study from the composer and their score to the production of which the incidental music is just one part. I argue for the use of performance-centred methodologies as a way of centring the production rather than the score, allowing for the analysis of historical incidental music as a collaborative multimedia entity, not a solo-authored musical ‘work’. I use as a case study the 1926 production of August Strindberg’s Till Damaskus (III) (‘To Damascus’) at Stockholm’s Concert House, directed by Per Lindberg (1890–1944), with stage and lighting design by John Jon-And (1889–1941) and music by Ture Rangström (1884–1947). Taking the production as the object of analysis allows for the exploration of questions about how early twentieth-century audiences might have understood meaning in Till Damaskus (III), questions that are difficult if not impossible to answer when focusing predominantly on the music in isolation. Furthermore, being able to understand the significance that particular productions might have held for their audiences helps, in turn, to understand how incidental music contributed to theatrical culture. In the case of Till Damaskus, I demonstrate that the music was vital to audiences’ perceptions of the production as ‘modern’, despite the fact that Rangström’s score uses what was, by 1926, a relatively conventional musical language.

Performance studies methodologies are highly dependent on ‘experiential knowledge’, assuming that the spectator is present at the production in question – an obvious problem for studying historical productions.Footnote 6 As Frantisek Deak writes, ‘The theatre scholar who accepts the premise that theatre as art exists in performance […] has no tangible, material subject from which to create his discourse.’Footnote 7 Deak’s solution to this dilemma is reconstruction (piecing together as much as possible about the play as it was performed) which he argues must be the starting point of historical enquiry into theatrical performance.Footnote 8 Even where detailed records of a show exist, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to reconstruct a production with any certainty. Inevitably, ‘The reconstructed production is both the work and its interpretation.’Footnote 9 Perhaps ‘re-creation’ is therefore a better term than ‘reconstruction’. This is not to say that historical performance analysis should not be attempted – simply that focusing on historical performance means accepting a certain level of conjecture and approximation, and that the possible conclusions that can be drawn about the production in question are always subject to revision.

One solution that Jens Hesselager proposes to bridge this historical gap is ‘reflexive performance’ – using performance as ‘an academic mode of interacting with the past’.Footnote 10 He does not propose trying to perform an entire play, ‘an event that is “full”, “total” or “synthetic” in nature’, but instead proposes using the performance of specific scenes as analytical tools to interrogate ‘hypotheses or arguments which are “focused”, “partial” or “analytical” in nature’.Footnote 11 He argues that this kind of reflexive, analytically oriented mode of performance can assist in asking questions ‘concerning the interaction between texts and performers […] to ask “how was this text used?”, or “what past actions does this text testify to?”’Footnote 12

While reflexive performance can certainly be used to ask questions about textual interaction, as Hesselager demonstrates, I argue that reflexive performance can also be useful if combined with other analytical methodologies when asking more theoretical questions about theatrical meaning. In 2015 and 2017 I organized two reflexive performances of scenes from Till Damaskus (III) with Rangström’s music, and I draw on these here to inform my analysis of the production in its historical context. I first use the reflexive performances to demonstrate a semiotic approach, using Jiří Veltruský’s model of theatrical semiotics to establish how this production might have created meaning for its audiences. Second, I incorporate semiotics into Lars Elleström’s theory of intermediality to shift the emphasis to audience perception, examining how audiences might have perceived the interactions between media in Till Damaskus (III).

Neither reflexive performance was anywhere close to the original circumstances of the production: the 2015 performance was in a small chapel with no costumes or lighting design and only a few hours’ rehearsal, and the 2017 performance constituted a single semi-staged scene with costumes but no lighting design, also with minimal rehearsal. Nonetheless, these reflexive performances allowed me as an analyst to engage in a process of critical spectatorship. One of the problems of studying historical performance is the distance the analyst has from the ‘materiality of performance’,Footnote 13 which denies them the experiential knowledge that is the ‘cornerstone of performance studies’.Footnote 14 I do not claim that reflexive performance can emulate the original circumstances of a production, but as I discuss below, it can provide an analytically valuable form of experimental knowledge, and inflect hypotheses developed through the analysis of textual documentation of historical productions. Performing specific scenes allowed me to contextualize many of the comments that reviewers made about their perceptions of meaning in the production. Furthermore, these performances illuminated gaps in understanding between early twentieth-century audiences and my own perspective as a twenty-first-century scholar, emphasizing the contingency of any claims made about historical theatrical meaning.

Why Till Damaskus (III)?

Heard outside the context of its original production, Rangström’s music for Till Damaskus (III) is relatively unremarkable. It constitutes 17 cues including a Prelude, underscoring and entr’actes, all scored for violins, soprano-alto-tenor-bass choir, organ, piano and percussion (see Table 1), none of which would bear performance as a stand-alone concert piece. For a piece written in 1926, its musical language is unadventurous. Cues are not always in a clear key, but they do not come close to atonality. Rangström never reworked the incidental score into a concert suite, and it has consequently remained unpublished and unrecorded. Viewed from either a musicological or theatre studies perspective, it is completely understandable why this music has not been examined extensively by scholars. Leaving aside theatre studies’ historical prioritization of the visual over the sonic, given that performance studies as a field was intended to ‘rejuvenate ossified academic or interpretative traditions’, even more recent theatrical considerations of sound have focused on radical and avant-garde aspects of sound design rather than the incidental music associated with theatrical traditions that performance studies scholars were trying to reject.Footnote 15 And from a musicological perspective, Rangström’s music runs completely counter to the expectations of the musical work as laid out by Jean-Jacques Nattiez: ‘The thing that ensues from the composer’s creative act is the score; the score is the thing that renders the work performable and recognisable as an entity, and enables the work to pass through the centuries.’Footnote 16 Incidental music, opera and music for the concert hall are written in very different ways and have different rubrics for success. As Rangström’s music is designed to interact with a spoken text and the production’s visuals, it is neither discrete nor easily reproducible.

Table 1 Musical cues in Till Damaskus (III)

| Cue | Text | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1, Preludium: Lento | - | Introduces the drama. Largely revolves around a B♭ pedal, acting as V of E♭. |

| 2, Procession: Andante | Act 1: The Confessor ‘Yes. The sun has entered’ | Funeral-style march in F♯ minor that accompanies the pilgrim’s procession. Scored for the entire ensemble. |

| 3, Andantino molto espressivo | Act 1: The Confessor ‘Have you ever seen something impossible?’ | Short, devotional cue scored for organ. Underscores the Stranger requesting to see his daughter. Largely in D minor. |

| 4, ‘Ad lib’ | Act 1: The Stranger ‘And oblivion, and songs, and power’ | Underscores the Stranger’s monologue. |

| 5, Adagio | Act 1: The Stranger ‘Therefore, you see, I will believe’ | Short cue scored for organ and choir, underscoring a conversation between the Lady and the Stranger about belief. |

| 6, Andante | Act 1: The Confessor ‘Then come!’ | Combines motifs from cues 1 and 5, accompanying the Confessor and the Stranger as they reach a crossroads. |

| 7, Lento | Act 2: The Stranger ‘What are those patients?’ | Continues the combination of motifs from cues 1 and 5, underscoring the Stranger and Confessor discussing the syphilitic figures. |

| 8, Andantino espressivo | Act 2: The Lady enters, pensively, and sits down | Reprises the theme from cue 3 in E minor, later modulating to E major. |

| 9, Adagio | Act 2: The Confessor ‘Go in peace!’ | Variation on the motifs of cue 5, accompanying the Confessor’s dismissal of the Lady. |

| 10, Allegro | Act 2: The worshippers of Venus get up | Accompanies the worshippers of Venus approaching the Stranger, and the Tempter’s entrance. Uses many melodramatic tropes such as fortissimo chromatic scales, tremolos and diminished chords. Also alludes to the violin solo of cue 4. Introduces a ‘lament’ motif, in which the choir sing ‘Sulphur’ to a descending augmented second. |

| 11, Lento | Act 2: The Tempter ‘Come, come!’ | Extended cue between Acts 2 and 3, which introduces a ‘Temptation’ motif. |

| 12, Vivo, agitato | Act 3: The Tempter ‘Eve! Come forward Eve!’ | Underscores Eve’s trial, and the appearance of the serpent. Uses melodramatic tropes similar to those of cue 10, concluding on a thundering cadence from G♯ to C minor in a fortississimo tremolo. |

| 13, Largo | Act 3: The Tempter ‘Come, I’ll show you the world you think you know’ | Mock fugato-style cue, with interjections of fortissimo scales whenever the Tempter speaks. Underscores the Tempter and the Lady’s argument over who will lead the Stranger. One of the longest cues in the score, it underscores their entire conversation, breaking into a D♭ major Adagio in the middle of the Lady’s monologue, when she begs the Stranger to come with her by invoking the memory of their dead child. |

| 14, Poco lento | Act 3: The Stranger ‘And I down’ | Reprises the cue 3 theme, again in D minor but concluding with a tierce de Picardie. |

| 15, Adagio | Transition from Act 3, scene ii, to Act 3, scene iii: The Stranger ‘Welcome to my house, beloved’ | Underscores the Stranger and the Lady discussing love. |

| 16, Poco largo | Act 3, scene iii | It is unclear where this cue would have started, but it played throughout the scene change between Acts 3 and 4, concluding when the Confessor says ‘Peace be with you!’ It presumably ran straight into cue 17, as Lindberg wrote in his script ‘Music carries on’ between the two cues. |

| 17, Lento, andante | Act 4 | Underscores the whole final act. The majority of the act was cut, leaving only a short conversation between the Confessor and the Stranger, and the introduction of the Prior. The cue carried on until the close of the play. |

The very label ‘incidental music’ is indicative of its status, carrying predominantly negative associations. Roger Savage notes that ‘incidental music’ derives from the German Inzidenzmusik, which does not have ‘trivializing connotations […] such as “fortuitous”, “casual”, “not strictly relevant”’,Footnote 17 but these are nonetheless the pejorative associations that the English term holds today. This is reflected in the Methuen Drama Dictionary of the Theatre’s definition: that incidental music is ‘music that is specifically written for a play but does not form an integral part of the work’.Footnote 18 By this definition, incidental music, even when written for a specific production, is quite literally incidental to the production in question – peripheral, inessential and extraneous to meaning on the stage. I would prefer to dispense with the term ‘incidental’ music altogether, and to adopt something more value-neutral like ‘theatre music’, but this term has such wide-ranging applications that it ceases to have specificity. ‘Theatre music’ would possibly encompass, besides other genres, musical theatre, vaudeville, melodrama and opera, whereas ‘incidental music’ refers specifically to music used in theatrical productions where the primary focus is not the music.

Savage opts for a more inclusive definition: ‘music performed as part of the performance of a spoken drama’.Footnote 19 This is my preferred definition, as it does not make any claims about the value of the music within the production. It also accommodates both music that is specifically composed for the theatre, and music that was composed for another purpose but is used in a theatrical production. Nonetheless, Savage’s definition indicates why incidental music has historically been considered unimportant by musicologists. Incidental music is only ever part of a theatrical production, not the primary focus as it is in opera or concert music, and therefore the composer’s authorial power is dispersed.

Issues surrounding musical value have already been interrogated by scholars of melodrama, computer game music, film and even opera, but incidental music has yet to benefit from the reassessments of value within these subdisciplines, despite its obvious similarities to these forms. If anything, incidental music has perhaps suffered from the relative rise of these subdisciplines, especially opera studies. In theory, the development of opera studies as a discipline that seeks to move the emphasis from ‘“text” or “discourse”’ to ‘“performance” and “the performative”’ could also have served to draw attention to incidental music.Footnote 20 But even when performance is the primary focus of attention, opera scholars frequently accord opera a higher status than incidental music, with the result that the flourishing interest in opera performance has simultaneously served to disadvantage incidental music. David Levin, for example, states that, compared with theatrical performance, ‘opera raises the stakes on account of its characteristic surfeit of expressive means.’Footnote 21 The assertion that opera is more capable of a ‘surfeit of expressive means’ than theatre is a distinctly musicological perspective, and one that no doubt many theatre scholars would disagree with. Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker, meanwhile, state that opera is comparable to ballet in the way it ‘brings into play unfolding systems – musical, visual, and textual – that occupy the same temporal continuum’, but avoid theatre as a comparison point altogether.Footnote 22 Despite opera scholars’ reluctance to admit it, however, there are enough similarities between opera and incidental music that there is much to be gained by applying performance-centred methodologies already used for opera to incidental music.

It is the disciplinarily determined valuelessness of Rangström’s music that makes it so valuable as a case study here, demonstrating what stands to be gained by understanding incidental music as part of a larger production. Acknowledging and exploring productions like Till Damaskus (III) gives a much richer comprehension of musical and theatrical life during the early twentieth century, drawing attention away from the opera house and concert hall to spaces where composers explicitly worked as collaborators rather than as solo authors. Rangström’s contribution to Till Damaskus was inescapably collaborative, and is well described by Eric Clarke and Mark Doffman’s model of collaborative work, where musical creativity arises from ‘combined labour in which the work of one person combines with, changes, complements or otherwise influences the work of another (or others), and is in turn influenced by it’.Footnote 23 David Roesner’s collection of interviews with contemporary theatre composers illustrates how collaborative the process of writing incidental music is, with composers having to make changes throughout the rehearsal, and needing to adapt to the abilities and constraints of the actors as well as taking into account the other elements of the production.Footnote 24 Rangström’s score for Till Damaskus makes explicit the dispersal of authorial power from one individual to a nexus of multiple collaborators; as was often the case with incidental scores written for a particular production, it bears the mark of changes made during rehearsal, either in the composer’s hand or in that of others.Footnote 25

Considering Rangström as part of a collaborative team provides a framework of reference through which to examine the multiple different discourses in which he was engaged. I have previously argued elsewhere that ‘as a multidisciplinary collaborative art form, theatre is uniquely placed to illuminate competing attitudes towards the concepts “modern” and “modernism”’,Footnote 26 and this is especially true of Till Damaskus (III). This production gives important context for understanding Rangström’s reluctance to write atonally. Sweden has not received a great deal of attention in the recent proliferation of scholarship on Nordic music, perhaps because the country’s most famous composers – Rangström, Wilhelm Stenhammar (1871–1927) and Hugo Alfvén (1872–1960) – wrote music well into the 1940s that sounds relatively regressive when compared with their Scandinavian contemporaries such as Sibelius, Nielsen and Grieg.Footnote 27 Rangström was staunchly opposed to atonality, and spent much of his time as a critic arguing against it as a modern direction in concert music (he would later write scathing reviews of Schoenberg’s work in particular).Footnote 28 But the theatre provided a space where this argumentation was unnecessary. In the Swedish theatre, it was not expected that music be atonal to be considered modern: tonal, accessible music was highly valued in its day – often by ‘avant-garde’ directors – for its dramatic impact. When viewed from an interdisciplinary perspective, atonality becomes less significant as a twentieth-century modernist marker. While a composer’s idiom might have been considered regressive in a concert hall, when placed in the context of an avant-garde theatre production the same music could take on new meaning and be heard as progressive and modern – even theatrically modernist.Footnote 29

Even when defending eighteenth-century melodramatic music from musicological narratives of progress and attendant attitudes towards musical cliché, Katherine Hambridge and Jonathan Hicks stress that melodramatic music ‘could in fact be thought of as avant-garde’, given that when melodramatic scores were first introduced in the eighteenth century, they ‘featured some of the most idiosyncratic music of their day’ owing to their fragmentary construction and ‘bold gestures, sudden gear changes, and prolonged harmonic uncertainty’.Footnote 30 In the eighteenth century ‘such elements as tremolo strings, diminished-seventh chords and swirling scalic runs to convey atmosphere’Footnote 31 may well have been considered avant-garde, but by the twentieth century these gestures were well established and had moved from being considered idiosyncrasy to being regarded as stock tropes. Although many composers used the theatre as a platform for musical experimentation, certainly where popular theatre is concerned musical clichés were widely used long into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and a vast quantity of incidental music from this period is tonal.

If the need to prove avant-garde status exists for eighteenth-century music, it has been even more acute for music of the early twentieth century. The persistence of tonality and recognizable musical tropes in incidental music runs counter to the imperative of ‘originality’ that has been both ‘the test of strength for any aesthetic modernist’ and fundamental to twentieth-century modernist musicological narratives.Footnote 32 The dictum of originality and innovation has allowed incidental music to be easily dismissed as being not just irrelevant, but actively regressive and counter-productive to the modernist project. The range of incidental music used in the early twentieth century was diverse, and included such avant-garde offerings as Germaine Albert-Birot’s score for Guillaume Apollinaire’s Les mamelles de Tirésias. Footnote 33 Nearly all of the incidental music from this period, however, was less experimental and used a substantial quantity of musical ‘cliché’. But these clichés were used precisely because they had become so familiar and were therefore extremely dramatically effective: an audience can only recognize a musical cue as connoting a certain emotion if they are familiar with the musical lexicon involved. Early twentieth-century incidental music involving clichés is only low-value if your question is, ‘Is it compositionally original?’ If we want instead to ask, ‘How did audiences interpret their experience?’ or, ‘How were the characters portrayed?’ then this music becomes of high value indeed.

With audiences ranging from the hundreds to the millions, particularly before the advent of film, popular theatres were some of the largest venues in which members of the public would interact with professional – or indeed amateur – music-making.Footnote 34 Historically, incidental scores have ranked among composers’ best-known pieces.Footnote 35 Rangström’s music for Till Damaskus (III) was heard by thousands of people during the play’s run at the Concert House, which had a seating capacity of 2,000. Understanding how his music contributed to the creation of meaning in this production, therefore, has the potential to provide insight into how music more broadly was an active part of theatrical culture in early twentieth-century Sweden, helping to shape theatre-goers’ attitudes towards the issues addressed within the play.

Investigating how historical audiences might have understood meaning in a production, however, can be a frustrating line of enquiry, largely thanks to incidental music’s ‘unheard’ quality. In some cases, trying to establish how spectators interpreted the music can be extremely difficult, because as Sarah Hibberd notes of melodrama, ‘the musical component was largely ignored by theatre and music journalists alike’, resulting in ‘scant evidence of its reception’.Footnote 36 This is exacerbated by the fact that very few incidental scores of this period have been published, or the scores and parts preserved in any coherent fashion, leading to the perception that incidental music was either negligible or not present at all. Archival absences are a self-fulfilling prophecy where assigning musical value is concerned: music thought unworthy of preservation is excluded from archives, leading to the belief that it doesn’t exist or doesn’t matter, so it isn’t archived. But reviewers did not ignore the music because it was not there or did not matter. Often they felt that they did not have the relevant expertise to talk about the music.Footnote 37 But more significantly, as in film, audiences did not always register that they were hearing music at all. Usually incidental music works ‘behind the scenes’, an ‘unheard’ force that subconsciously contributes to an audience’s perception of meaning within a production.

The ability to manipulate and shape audience response in an ‘unheard’, subliminal way is one of the most pressing reasons for scholarly attention to be paid to this music. It can be a powerful ideological tool, entrenching stereotypes or undercutting paradigms in ways that audiences do not consciously register. This capability led to modernists’ historical fascination with, and unease about, music in the theatre, with many calling for music to be either dispensed with entirely, or significantly reformed. To quote a well-known example, Bertolt Brecht aimed to use music as Verfremdungseffekt, and cautioned that ‘the effectiveness of […] music largely depends on how it is performed’, and that actors needed ‘careful education and strict training’ to ‘realize the right gestus’ and not have the music ‘simulat[e] the effects of dope’.Footnote 38 He was particularly scathing of operatic and orchestral music of the nineteenth century, complaining that it was ‘impossible […] to make any political or philosophical use of music’ that leaves audiences in ‘a peculiar state of intoxication, wholly passive, self-absorbed, and according to all appearances, doped.’Footnote 39

The Russian symbolist Leonid Andreev adopted a similarly cautious approach. He promoted the use of music in the theatre, calling music ‘psychism’s most direct and sharp weapon’.Footnote 40 But because of its potential power, Andreev denounced background music, precisely the ‘unheard’ music that constitutes the majority of incidental music, that is introduced ‘by means of an itinerant orchestra which suddenly appears out of nowhere’. He argued that ‘as a proven necessity in the new theater, music has a very great and important place’, but also cautioned that if it remained ‘a dismal “Song without Words,” it will disappear’.Footnote 41 Taking incidental music seriously helps to contextualize arguments like these – Brecht and Andreev’s objections do not make sense unless incidental music was both widespread and thought capable of wielding significant influence.

Although the ratio of reception documents to quantity of theatre music is low, it is important not to ignore the contemporaneous accounts of incidental music of this period that do exist. The ‘ephemeral nature of [theatre music’s] materials’Footnote 42 is sometimes overplayed. There are theatre archives which hold substantial records of incidental music, and these indicate that the presence of relatively extensive music was commonplace in large, well-funded theatres.Footnote 43 In some cases, famous composers’ names were used to draw audiences to new productions. They would appear on the publicity material for a play, presented as an opportunity to hear a new piece by an esteemed composer, and sometimes music was listed as one of the production’s main attractions.Footnote 44 In these instances, newspapers would sometimes publish preview articles on the music in question, and reviewers would comment extensively on the sound of the production as part of their commentary. The 1926 Till Damaskus (III) is one such example. The production received a large amount of critical commentary, so there is extensive documentation about not just how but what meanings might have been perceived in this production. Many of the reviews discuss the music specifically. Of course, the reviewers represent only a small proportion of audience members – and an unrepresentatively well-informed audience segment at that – but their writings nonetheless give an insight into the kinds of meanings perceived by at least some of those audience members.

Till Damaskus, then, provides an example of incidental music by a composer who is now ‘non-canonic’ but whose music reached wide audiences during his own lifetime through the theatre. Additionally, there are extensive documents relating to the production held at the Musik- och Teaterbibliotek in Stockholm. Both Rangström’s score and Lindberg’s copy of the script are held at the library – including enough annotations between them to establish approximately where all of the musical cues were placed – alongside reviews, stage designs, Lindberg’s personal notebooks, Rangström’s personal documents including his own writings about Strindberg and about Till Damaskus, and photographs of the production. In combination, these provide sufficient materials to attempt a reflexive performance of scenes from the play.

Till Damaskus (III) and reflexive performance

The reflexive performances of scenes from Till Damaskus (III) had two express purposes. The first was to explore, as Hesselager does, questions about media interaction, including: how might text and music have coincided? How might the music have shaped actors’ movements? How might music have affected the timing of any given passage? But the second purpose was to take the answers to these questions and use them to explore questions about meaning. I wanted to try to understand why the critics in 1926 had understood the performance in the ways that they did, and what this might reveal about the role of this kind of theatre in Stockholm society more broadly. So the second set of questions explored how music might have contributed to meaning – how did the music shape characterization and scene building? Did it create a sense of place, and if so, how? Did the music seem to be supporting or undercutting the text? How does one inflect the interpretation of the other?

Till Damaskus is a semi-autobiographical trilogy of station dramas that Strindberg wrote between 1898 and 1904, meditating on the nature of religion and gender relationships. The third part follows the Stranger (Den Okände – representing Strindberg himself) on his journey to spiritual redemption, helped by the Confessor (Confessorn – a manifestation of the Stranger’s virtuous self) and hindered by the Tempter (Frestaren) and the Lady (Damen) – the former representing the Stranger’s sinful self, the latter the temptation of both sexual and maternal love. Despite Strindberg’s fame, Lindberg’s 1926 staging was only the second production of this particular play in Sweden. It was largely considered unstageable thanks to a combination of Strindberg’s excessive stage directions and the meandering, quasi-philosophical text that constantly shifts perspective between dreams and reality.Footnote 45 To produce a plausible rendering, Lindberg made extensive cuts to Strindberg’s text and opted for a staging that made little distinction between reality and unreality throughout, for which both music and set design were crucial.

Answering my first set of questions necessitated first determining what music was played when and where. It is relatively straightforward to place the starting point of some cues, as Rangström wrote a specific line into his score that is corroborated by Lindberg’s script, for instance in the case of cue 3. But others, such as cue 16, are more ambiguous, where neither script nor score indicates a precise start-point for the musical cue. Because of the nature of historical performance analysis, even the most basic questions – such as what music went where – can benefit from reflexive performance, using a process of ‘trial and error’ to ascertain likely combinations of music and text. The positioning of the musical cues suggested in Table 1 is, therefore, very much my interpretation of the available sources, guided by two reflexive performances. The first performance, in 2015, involved a small group of colleagues and students performing the music and text for cues 1 (the Prelude), 3, 4 and 12 (all underscoring).Footnote 46 The second, semi-staged performance (with musicians and costumed actors) was of cue 13, an extended cue which underscores one of the play’s pivotal dialogues, and took place in 2017.Footnote 47 I chose these cues precisely because they seemed, textually, relatively determined; they all have seemingly explicit directions about where the music starts, and even directions for where particular lines coincide with musical gestures throughout the cue. Nonetheless, we still had to make a large number of choices about the pacing of the music and speech, and in each case the choices we made significantly altered ‘the character and timing’ of the given passage.Footnote 48

As Hesselager found in relation to his analysis of the 1829 melodrama Sept heures, performing the cues from Till Damaskus (III) provided ‘insight into the types of choices that would have been made in such performances’, and also ‘what type of expertise was required of actors and musicians’.Footnote 49 Cue 4, for example, calls for an organ, piano, violins and solo violin to underscore a monologue given by the play’s protagonist. We performed the scene in a small chapel with a much smaller organ than was used for the original production in Stockholm’s Concert House with an auditorium that seated 2,000 people, but even when the instrumentalists were asked to play extremely quietly, our actor had difficulty projecting over the ensemble. He found he had to change his style of declamation in order to be heard – the ramifications of which I discuss in more detail below. Our experience performing this scene suggests that the actors involved in this production would have had to be trained to project over relatively large instrumental forces, as otherwise, even though the orchestra was in a pit, there would have been little chance of them being heard. Or, alternatively, it is possible that audience members sitting towards the back of the auditorium would have had difficulty hearing the text in heavily underscored moments such as these.

Reflexively performing cue 13 also gave significant insight into how the presence of music might have influenced actors’ movements. The actors moved and spoke much faster when they performed the scene without music, compared with when the music was added. They found that the music slowed down their actions and allowed them to incorporate more elaborate gestures that they considered ridiculous without the music. This, then, opened up one commonality that this early twentieth-century repertoire shared with melodrama of previous centuries: a vocabulary of visual signification. Strindberg is not a playwright associated with melodrama; if anything, quite the opposite. His characters are psychologically complex, eschewing the moral binaries that characterize melodramas, and like Ibsen, Strindberg embraced realism in many of his plays. Nonetheless, despite the textual distance from melodrama, performance practices provide areas of continuity with Strindberg’s theatrical predecessors. Hesselager observes that ‘the predominantly visual quality of melodramatic performance’ might ‘be closely connected with the use of music: orchestral accompaniment makes it possible to expand the duration of a wordless moment, so as to allow time for a visual spectacle to unfold around it’.Footnote 50 This was precisely the experience we had with cue 13 of Till Damaskus (III): visual and sonic expansion were interlinked. Strindberg’s intentions may have been to distance himself from melodrama and write ‘modern psychological drama’,Footnote 51 but he could not control how his plays were staged after his death in 1912. The choices that we had to make when performing this scene suggest that the 1926 production of Till Damaskus might have had continuities with nineteenth-century melodrama in its modes of visual presentation, even if not in its textual content.

From these observations we were able to move to questions about theatrical meaning. Across all the commentary about Till Damaskus, there was a general agreement about the purpose of the music. While authors did not go into detail on specific musical moments, several gave enough of their general impressions to posit some hypotheses about how at least some audience members understood the music’s contribution to meaning in the production. The reviewer for Social Demokraten, quite possibly the composer Patrik Vretblad (1876–1953), stated that the purpose of the music

was twofold: first, to colour some scenes with notes of a formless, fantastic nature, and second, to give expression to moments of religious contemplation with music of more solid form. […] The organ has found a use here that can hardly have been imagined when it was erected in a secular venue.Footnote 52

The author Daniel Fallström penned a review for Stockholms Tidningen, and agreed with the assessment that the music created a religious atmosphere. Further, he intimated that Rangström’s music made up for what was lacking in Jon-And’s scenery. In effect, it ‘filled in’ the conceptual gaps created by the scenery and script:

When the spectator has his gaze pinned to the same spot scene after scene, he must have an exceptional imagination to go on the mountain climb [to the monastery]. In a recent interview Gordon Craig has warned against over-stretching the viewer’s brain. And that is what Per Lindberg does to a certain degree – and has to do – when he does not have extensive scenic resources at his disposal. There [the production] is lacking.

But instead he has something that no other theatre in the world possesses: an organ of such powerful effect that one believes that one is transported to a mighty cathedral. And this organ gave wings to yesterday’s audience’s imagination and devotion and lifted it high above the present; it filled what the stage space could not provide and turned the Concert House into a holy place.Footnote 53

For Fallström (who was not a musical expert), it was the music that not only made the play stageable, but made it convincing: in the face of scenic difficulties, it was Rangström’s contribution that conveyed the sense of religiosity necessary for Lindberg’s production to succeed, and offset the potential monotony of the staging. I wanted to use the reflexive performances, then, to try to understand why critics heard the music in this way, and how this shaped their perception of meaning in the production. To do so required moving beyond Hesselager’s questions about interaction to engage with theatrical semiotics.

A semiotic approach to Till Damaskus (III)

By considering everything that is involved with a given performance – from the onstage props to the theatre itself – as a sign, semioticians attempt to understand ‘how meaning is produced in the process of creating, viewing, analysing, and recording a piece of theatre’.Footnote 54 Within this model, meaning is framed ‘as a process, something that is provisionally produced by communities, technologies, and cultures engaged in various kinds of social, economic, technological, and pedagogical relationships with one another’.Footnote 55 This provides a foundation for an inescapably intermedial model in which music is just one among an interacting network of signs, and in which contingency of meaning and the centrality of interpreters is foregrounded. As Ric Knowles explains, a production’s possible meanings are ‘produced by specific audiences in particular places and times, and these are determined in large part by the local conditions of production and reception’.Footnote 56

Semioticians including Jiří Veltruský have already begun to move towards incorporating music within their models. He writes that in the theatre, ‘every product of another art may lose some of its properties and acquire others’,Footnote 57 and that even music that was written to be ‘absolute’, when placed in a theatrical context, ‘can take on a set of functions in which its own aesthetic function is relegated to a quite subordinate position as an auxiliary element’.Footnote 58 Veltruský’s semiotic model is particularly illuminating because he argues that placing music within the theatre means that it is experienced in an explicitly multisensory way. He notes, for example, that, ‘The actors’ physical performance may give far greater prominence to rhythm than does the music itself, sometimes even turning it into the dominant feature and relegating all the other components to merely auxiliary functions.’Footnote 59 His use of ‘the music itself’ here is problematic, but his point stands that performing a piece of music in a theatrical production as opposed to in a concert hall setting alters which musical elements are foregrounded in a spectator’s consciousness, and how they are consequently interpreted, on account of their interaction with the other media present.Footnote 60

Marvin Carlson argues that, ‘The way an audience experiences and interprets a play […] is by no means governed solely by what happens on the stage.’Footnote 61 Before an audience engages with onstage action, they are already interacting with a system of signs that includes the creative team behind a production, the names and reputations of the actors, ‘the entire theatre, its audience arrangements, its other public spaces, its physical appearance, even its location within a city’, all of which are ‘important elements of the process by which an audience makes meaning of its experience’.Footnote 62 When Lindberg came to stage Till Damaskus (III) in Stockholm in 1926, he enjoyed a reputation as Sweden’s most radical director. He had studied with Max Reinhardt in Germany, after which, in 1919, he took up a position as the artistic director of the new Lorensberg Theatre in Gothenburg. Building the Lorensberg in 1916 had formed part of an attempt to establish Gothenburg as both a cultural and an economic rival to the Swedish capital. In 1909 the newspaper Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning ran a survey of local cultural figures, asking their opinions about Gothenburg’s lack of a theatre. The general consensus was that Gothenburg desperately needed a theatre, and that any theatre in the city should stand in contrast to the example set by the Swedish Theatre and the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Stenhammar, as the conductor and artistic director of the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, was invited to respond to the newspaper’s questionnaire, and he laid out his view in clear terms. He portrayed Stockholm’s theatres as being out of touch with the lower and middle classes, saying that because the Stockholm theatres were ‘expensively decorated and adorned’, the ticket prices had to be kept prohibitively high, limiting the possible audience to only the monied bourgeoisie. By contrast, ‘Our theatre’, he wrote, ‘will be big, so that there are seats – and cheap seats – for many, the house will be erected simply and without obtrusive finery, so that even the lowly in society dare venture into it.’Footnote 63

When it came to the purpose of theatre, and who the theatre should be for, Stenhammar’s and Lindberg’s perspectives were aligned. Heavily influenced by his mentor Reinhardt, Lindberg also believed that theatre productions should be widely accessible, and that the first step towards making theatre accessible was to dispense with realist theatrical styles. Ushered in by pioneers like Ibsen and Strindberg with their plays A Doll’s House and Miss Julie, realism involved creating as lifelike a setting for plays as possible. As Toril Moi argues, Ibsen’s embrace of realism was based on a rejection of idealism, the idea that ‘beauty, truth, and goodness were one’, which had underpinned the moral binarism of melodrama.Footnote 64 The theatrical world in which Lindberg had grown up (quite literally – both his parents were actors) was one in which detailed sets were designed to evoke a specific time and place, and the large orchestras that had provided underscoring for plays and melodramas in the early nineteenth-century were banished. Because of the imperative to make the scenes as realistic as possible, ‘Serious drama […] was suddenly music-free.’Footnote 65

Lindberg’s arguments against realism were threefold: it made theatre boring to watch; the costs of intricate realist sets kept ticket prices prohibitively expensive; and it was obsolete in Sweden’s post-war society.Footnote 66 Just as Ibsen had reacted against idealism, Lindberg reacted against realism, ushering in a period of spectacular, ostentatiously theatrical productions on Swedish stages, heavily influenced by Reinhardt’s circus shows and 1905 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The last was one of Reinhardt’s most influential anti-realist productions, and in Lindberg’s opinion, Reinhardt had ‘rebirthed a poetic work, he let the poem blossom through the theatre’s own expressive means: in sound, light, colour and line, to become a sensual and rhythmic art’.Footnote 67 Following Reinhardt’s example, Lindberg’s productions made use of the latest available stage and lighting technologies, were full of richly coloured costumes that were not necessarily historically accurate, and incorporated extensive musical scores. For Swedish audiences and critics in the 1920s, the presence of an orchestra and extensive score was innovative and associated with the new, anti-realist modern production style. Lindberg himself had a considerable amount of musical training and expertise, and considered the composers he worked with as core members of the artistic team. They were present throughout rehearsals, working alongside the director and stage, lighting and costume designers.Footnote 68 Hilding Rosenberg, for example, wrote about how he consulted with Lindberg throughout the compositional process for all the productions they collaborated on, moving between rehearsal room and writing desk in a constant process of negotiation and rewriting.Footnote 69

The Lorensberg productions quickly established Lindberg’s reputation as ‘the leading revolutionary force in Scandinavian theatre’.Footnote 70 In 1924 he left the Lorensberg, transferring to Stockholm in 1926 to launch a new project which he dubbed ‘the People’s Theatre’ (‘Folkteatern’). The motivation behind the People’s Theatre – modelled on theatres like Berlin’s Volksbühne and Vienna’s Volkstheater – was explicitly political. In promotional articles introducing the People’s Theatre, Lindberg wrote that there was an overwhelming need for ‘a democratic theatre – a theatre whose size could let it keep popular prices, without the theatre needing to curtail operating costs […] a theatre which dares to rely on the new audience in the new society, and stage interpretations of select repertoire for them’.Footnote 71 In particular, by aiming at a wide audience and keeping ticket prices low, Lindberg was intending his new theatre to be competitive with the cinema. He argued that theatres were facing a crisis, largely owing to their use of ‘outmoded means to defend [the theatre’s] place in cultural and social life against film’s affordability and overwhelming advertising resources’.Footnote 72 Lindberg was not alone in worrying about the impact of cinema on Swedish theatre, nor in seeing a revival of cheap, spectacular theatre as the solution. The author Bo Bergman defended the People’s Theatre, saying, ‘The challenge now is to draw people away from the cinema, as the cinema drew people away from realistic theatre.’Footnote 73

Lindberg selected as his venue Stockholm’s Concert House, which seated nearly 2,000. This was much smaller than Reinhardt’s Grosses Schauspielhaus, but it could seat nearly double the number of Stockholm’s largest theatre, the Swedish Theatre. Additionally, the Concert House had no associations with any particular type of production style, and had exceptional musical resources including an orchestra pit and an organ. Before audiences stepped into the hall, therefore, they were primed to understand the production in a particular way. In the midst of an extremely turbulent economic decade for Sweden, which in 1926 was emerging from a deep recession,Footnote 74 Lindberg’s policy of keeping ticket prices competitive with cinema and aiming to appeal to a broad demographic aligned his work with the political left. Even to those who did not read the papers or keep track of Sweden’s theatrical life, the Concert House as a venue would have signalled that this was an ‘anti-establishment’ production. Nonetheless, it was a measured form of anti-establishmentarianism; subscriptions were cheap (6–12 SKr for four performances) but not free,Footnote 75 and the People’s Theatre was still run by a small, select group of professionals – a far cry from the community-run proletarian theatre that had been emerging in Russia.Footnote 76 Lindberg’s ‘democratic’ theatrical vision was socialist, not communist.

Before Lindberg’s 1926 audience even entered the Concert House, then, they would have been expecting a spectacle. Till Damaskus (III) was part of the double bill opening the first season, alongside Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. Choosing to stage two relatively unknown plays by the best-known playwrights in Sweden signalled Lindberg’s ambition. Strindberg was unquestionably Sweden’s most famous playwright, with a reputation as an ‘arch rebel and social iconoclast, the most modern of the moderns’, which made him the playwright that every Swedish director had to stage if they were going to be successful.Footnote 77 And as mentioned above, this was only the second staging of Till Damaskus (III) in Sweden, so this play in particular was considered an additional challenge. The extensive press framing of the production, the building that it was staged in, and the reputation of the director all shaped the audience’s expectations, guiding how they heard and saw the play.

Once they entered the auditorium, audiences would immediately have been faced with the set. There was no curtain, which in itself constituted a difference from the more established theatres in Stockholm and helped to reduce the conceptual distance between the audience and the play’s world. The political cartoonist and Cubist artist Jon-And was Lindberg’s stage designer for Till Damaskus; together, he and Lindberg devised a set and lighting design that was unquestionably influenced by German Expressionism – the combination of a backdrop made up of geometric shapes, props taken from everyday objects and the thick, dark-eyed make-up donned by the actors made the whole staging redolent of Robert Wiene’s 1920 silent horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (see Figures 1–4). Both Lindberg and Jon-And were well aware of artistic developments in Germany: Lindberg’s notes for the production include an extensive commentary on its relationship to German Expressionism, saying that it was ‘self-evident’ that the production should have an ‘expressionistic character’.Footnote 78 Lindberg had intended to forge his own form of Expressionism, influenced by other Scandinavian experiments such as Johannes Poulsen’s at the Kongelige Teater in Copenhagen; nevertheless, the overwhelming impression – at least according to the reviewers – was of a production greatly indebted to German Expressionism. The most elaborate visual element of the staging was the lighting design. Combinations of coloured lights were used to create a surreal, dreamlike atmosphere, giving the geometric backdrop texture and depth.

Figure 1 Court Scene from Till Damaskus (III). All images reproduced by permission of the Musik- och Teaterbibliotek, Stockholm.

Figure 2 Olof Sandborg and Harriet Bosse as the Stranger and the Lady.

Figure 3 Ingolf Schanche as the Tempter.

Figure 4 Harriet Bosse and Olof Sandborg as the Lady and the Stranger.

Into this mix was added Rangström’s music. By 1926 he was hardly as famous as somebody like Stenhammar, but he was emerging as one of Sweden’s more promising composers. His name was already loosely associated with Strindberg: his First Symphony (1914) was dedicated to the playwright, and his opera based on his play Kronbruden (‘The Crown Bride’) had premiered in 1915. These associations were mentioned by some reviewers, noting that it made Rangström a particularly appropriate choice of composer for this production. For Rangström, Strindberg was a source of continual fascination. Not only did he uphold Strindberg as a founding father of Swedish culture, but he self-identified with the older playwright, mimicking Strindberg’s attempts to examine himself as a subject by writing fictionalized autobiography (Rangström wrote autobiographical poetry and fictional sketches, and many of his musical works have narratives or texts that are autobiographical in nature).Footnote 79 When composing for Till Damaskus, therefore, Rangström seems to have attempted to support what he perceived to be Strindberg’s meaning in the text, not to undermine or contradict it.

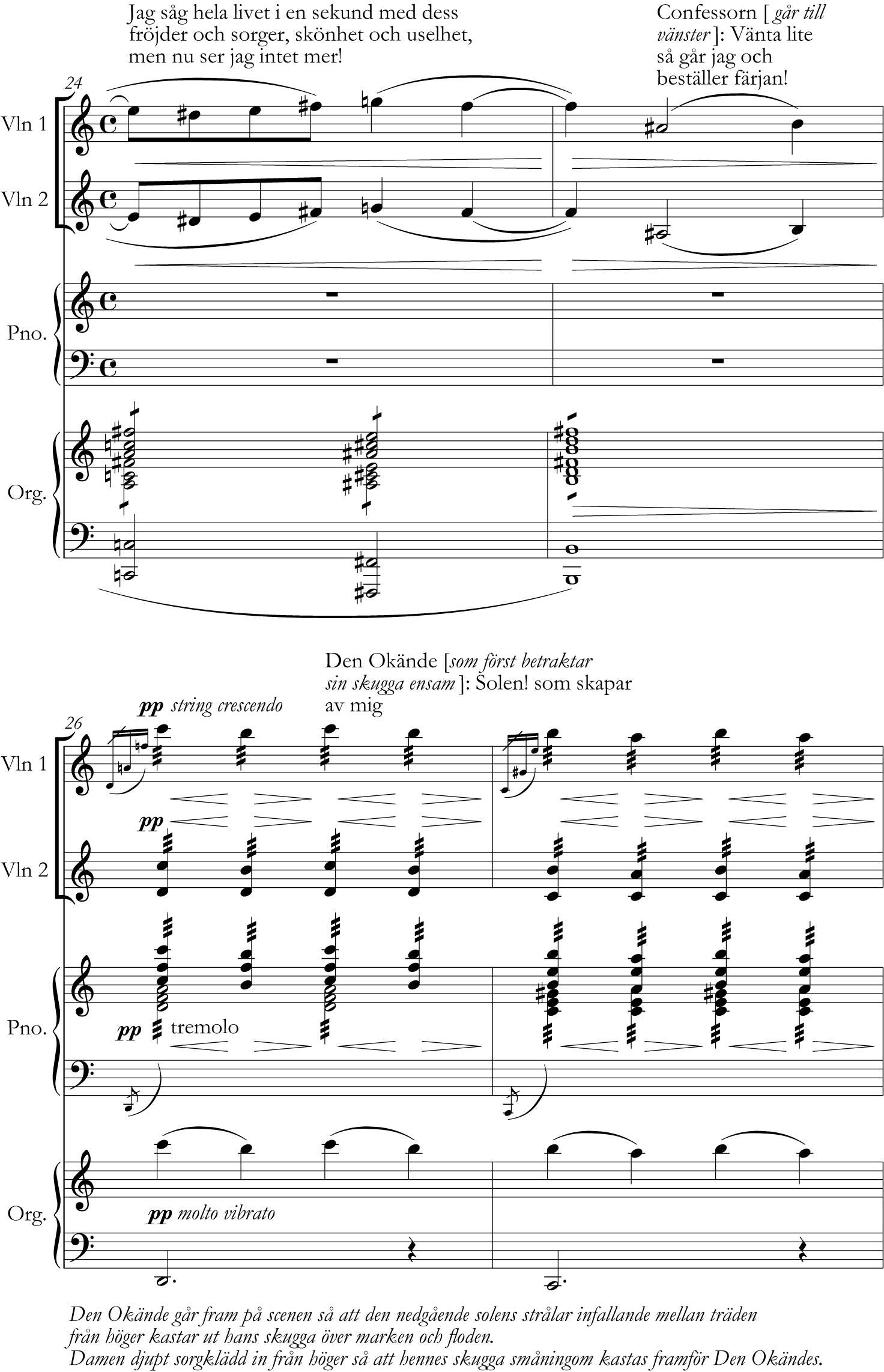

Rangström’s ‘faithful’ approach to the script, and his reputation as a Strindberg interpreter, helps to frame the critics’ understandings of how the music contributed to the production. The Prelude provides one such example of how, according to the critics, the music ‘filled in’ the scenery and blurred the conceptual reality between dreams and the real world. Because of the lack of a stage curtain, when the audience entered the auditorium they would have been faced with a stage filled with triangular shapes. As the production began, the lighting colour shifted to a ‘cold’ combination of blue and white, with some yellow in the centre lights.Footnote 80 While lighting can be used ‘to break up the theatrical space and set it in motion’, it can also be used to suspend motion.Footnote 81 On its own, the fixed lighting design would have rendered the stage static, but in this case the audience’s perception of duration – of movement in time – would have been shaped by Rangström’s music. Theorizing the impact of music in film, Michel Chion argues that, ‘Sound vectorizes or dramatizes shots, orienting them toward a future, a goal.’Footnote 82 This is precisely what Rangström’s Prelude achieves, giving movement to an otherwise static stage design. But it imparts less a sense of goal-direction than of circular movement, which is compounded by the repetitive uniformity of the shapes in the set. The Prelude opens on a B♭ tremolo in the strings – already creating a sense of suspension – against which the choir hums a two-bar chromatic phrase beginning and ending on B♭ (see Example 1). It is unclear whether the B♭ is a tonic or a dominant: there is no clear cadence until bar 14, where choir, organ and piano cadence into E♭, implying a B♭ dominant; but the strings maintain their tremolo throughout, undermining the stability of the cadence. This uncertainty pervades the whole cue: the choir’s part is wordless, there are no conclusive cadences and the cue ends with the same motif with which it began, revolving around B♭.

Example 1 Ture Rangström, music for Till Damaskus (III), Prelude, bars 1–4.

Even before the actors entered the stage, music, set, lighting and theatrical space all interacted to create meaning within this opening scene. Within a production that was expected to be anti-realist and avant-garde, audiences were presented with a scene that is suggestive of circularity, full of repetitive motifs in both music and set. This frames the entry of the Stranger and the Confessor as the musical cue draws to a close, underscoring the Stranger’s first line, ‘Why do you lead me along these winding, hilly paths that never come to an end?’Footnote 83 The opening scene establishes the uncertainty that is one of the Stranger’s key character traits, and shapes the action of the entire play. Even though the Stranger is not on stage for the majority of the opening scene, the Prelude here contributes towards characterization. Perhaps some audience members would have known Strindberg’s script already, and for them, the script might also have imparted meaning to the scene, encouraging an interpretation of the opening materials that emphasizes its ‘formless, fantastic nature’, as one reviewer put it.Footnote 84

Reflexive performance and intermedial analysis

The semiotic analysis provided above assumes that media are defined and perceived by authorship – Rangström’s music constitutes one medium and Jon-And’s set another, and each acts upon the other to create meaning. And while perception no doubt sometimes falls along these definitional boundaries, this is not necessarily always the case. In order to come to a more holistic understanding of perception and meaning in theatre productions, work by semioticians such as Veltruský can usefully be combined with frameworks proposed by intermedial scholars. Intermediality ‘deals with the transgression of borders between media, i.e. heteromedial relations between different semiotic sign systems’,Footnote 85 crucial to which is the definition of what constitutes a medium. It is not self-evident that ‘music’ should be considered a separate medium from ‘voice’, for example, when determining what constitutes a sign in the theatre. Exploring this problem, Lars Elleström with his theory of media modality proposes ways of dividing multimedia space not according to disciplinary boundaries (music, sound, costume, lighting and so on), but according to modes of spectator perception.Footnote 86 He proposes four complementary modes of perception: material, sensorial, spatiotemporal and semiotic. The material is the awareness of the ‘latent corporeal interface of the medium’, for example sound waves or the human body;Footnote 87 the sensorial are ‘the physical and mental acts of perceiving the present interface of the medium through the sense faculties’;Footnote 88 the spatiotemporal structures the experiences of the material and sensorial ‘into experiences and conceptions of space and time’;Footnote 89 and the semiotic is the ‘creation of meaning in the spatiotemporally conceived medium by way of different sorts of thinking and sign interpretation’.Footnote 90 Elleström argues that when conceptualized in this way, all disciplinarily conceived media ‘are more or less multimodal on the level of at least some of the four modalities’.Footnote 91 Following this model where the analysis of theatre music is concerned, therefore, suggests that asking what constitutes a musical sign is the wrong question – more pertinent is what constitutes a sonic sign, or an audiovisual sign, of which music constitutes one part. To conceive of a theatrical performance in this way automatically displaces the centrality of the composer – and indeed the music – and necessitates a more holistic view of the production.

If taken as an exclusive assumption for analysis, this form of media delineation runs the risk of sensory essentialism. It is important not to dispense entirely with the conceptual media boundaries which determine difference between art forms – what Elleström terms ‘qualified media’, such as music or sculpture.Footnote 92 Although there will be moments when spectators perceive primarily spatiotemporally, the conceptual boundaries of qualified media will be important to at least some spectators’ experiences of a given production – particularly those of reviewers, for example, who are trained to perceive in ways such that they can offer commentary on individual contributions to a production.Footnote 93 Nonetheless, spectators navigate between different modes of perception over the course of a single performance, and a semiotic analysis needs to be able to account for multiple modes of perception.

Cue 4, which underscores one of the Stranger’s monologues, involves such a moment where the combination of voice and instruments encourages an analysis that is not divided along the lines of qualified media. Throughout the play, Strindberg posits that there are multiple realities – or, indeed, unrealities – all of which exist simultaneously and overlap. Throughout the drama, it is ambiguous as to whether the action proceeds inside or outside the protagonist’s head; the other characters could be real, manifestations of his psyche, or figments of his imagination. The Stranger is continually questioning his senses – he appears to hear things others cannot, and it is unclear whether these sounds are heard by other characters or whether he is imagining them. In this monologue, the Confessor is preparing the Stranger for his journey to a monastery and hands him a cup of wine. He warns that the Stranger should not lose himself while contemplating the wine, as ‘memories lie at the bottom [of the cup]’. The Stranger does proceed to lose himself in his memories, describing sights and sounds that are seemingly perceptible only to himself.

On the page, this monologue is a moment of extreme interiority, where the sensory hallucination appears as an omen perceptible only to the Stranger himself. On stage, however, the audience is clearly privy to the Stranger’s recollections. Additionally, the presence of music radically alters this moment by externalizing previously inaudible sounds. At the start of the monologue the Stranger claims to ‘hear a song’ – Strindberg calls for no music here, but in Lindberg’s production the Stranger’s claim to hear would have come shortly after the musical cue began. Where, then, does this leave the audience – or, indeed, the Stranger? Does the audience enter into this interior moment with the Stranger, hearing inside his mind, or is he hearing a sound that is audible to all?

Speaking about Strindberg’s plays, Rangström commented that, ‘Strindberg was […] a musical pioneer, thanks to the inspired and unbelievably melodic movement of his language.’Footnote 94 By this he did not mean simply the quantity of music called for in Strindberg’s plays, ‘the places where he talks about, describes or prescribes music’; instead, Rangström was interested in ‘the music that lives in his poetry, closer to his heart than the visible words’.Footnote 95 The Stranger’s monologue offers one such example of Strindberg’s ‘musical’ language, which aspires to what Hesselager identifies as a quasi-operatic mode of spoken expression. He identifies ‘operatic’ moments as being of ‘heightened mood’, in which a theatrical character can allow themselves ‘unrestrained self-expression’ almost akin to that associated with an operatic aria.Footnote 96 This entire monologue is focused on the Stranger’s self-expression, constructed from ‘poetic’ language – it neither describes an event nor constitutes a call to action. It is perhaps the ‘musical’ way in which the speech is written that encouraged Rangström to underscore it, despite the fact that Strindberg does not explicitly call for any music.

The speech is split into two halves, divided by the Confessor’s interruption and the onstage appearance of the Lady, at which point the sun comes out. The first half is full of rhythmic repetition that focuses the entirety of this part of the speech on the inaudible and invisible sensory stimulus that preoccupies the Stranger. After his initial declaration that he hears a song (‘jag hör en sång’), the Stranger repeats variants of the phrase ‘jag ser’ and ‘jag såg’ (‘I see’ and ‘I saw’) no fewer than six times within the space of a couple of lines. This repetition is complemented by rhythmic internal rhyme, Strindberg twice rhyming ‘ser’ with ‘mer’. Although the text is explicit that he hears a song, the punctuation and repetition of the following statement render it extremely unclear as to what it is that he claims to see. The Stranger says, ‘I hear a song and I see! I see it … I saw it for a moment.’Footnote 97 What, here, is ‘it’? Possibly it is the song, although the exclamation mark’s abrupt interruption of the line leaves the verb ‘to see’ waiting for a definite subject, suggesting that there is an additional sensory source beyond the song. A sentence later the mystery is solved – the Stranger saw no less than ‘the whole of life’ flashing past him in an instant.Footnote 98

The second half has a different pace and sound, as the Stranger shifts from describing an invisible vision to imagining a galactic journey prompted by the appearance of the sun. Whereas the first half is dominated by assonance, the second half is full of plosives and sibilance, combining ‘s’, ‘b’ and ‘k’ sounds to give the voice a much harsher timbre than it had previously. The monologue is propelled forward by phrases like ‘kliver över klosterkyrkans tak’ (‘striding over the monastery roof’), and clusters ‘k’ and ‘v’ within a trio of ‘kl’ words (‘klättrar’, ‘kliver’, ‘klosterkyrkans’).Footnote 99 The change in poetic devices indicates the reorientation of the Stranger’s attentions, now engaging with the changing physical circumstances in the world around him.

Analysing the role of the voice in theatre, Konstantinos Thomaidis argues that, ‘Musicalizing speech through repetition, alliteration and rhythmicity […] gives prominence to the non-semantic aspects of voiced language and challenges conventional understandings of speaking as meaningful linguistic exchange.’Footnote 100 This holds true for cue 4, where, accentuated by Rangström’s setting, one of the most important functions of the Stranger’s voice is its role as sonic entity, above and beyond its function as a conveyor of linguistic meaning. While the text is ‘musical’ in the abstract sense when spoken unaccompanied, Rangström’s score treats the Stranger’s voice as an instrument in its own right. Snippets of the Stranger’s lines are indicated in the score, so music and voice were clearly intended to coincide at particular moments, blending the voice with the instruments. Nonetheless, this is a different kind of ‘musical’ voice from that used in song, as the correspondence between music and words is approximate rather than exact. Although rough cues are given, Rangström does not go so far as to annotate the Stranger’s part, allowing the actor playing the Stranger to adopt a more improvisatory approach within given parameters.

Rangström’s setting further ‘musicalizes’ the speech by weaving its bipartite structure into a larger musical form. Working out precisely where the music and text would have coincided is something of a guessing game, as Rangström’s annotations are far from extensive. Judging by the few that exist, however, it seems that the Stranger did not begin speaking until bar 18, after an extended violin solo. Underneath the forte in bar 21 Rangström wrote ‘som när en flagga’, and for these words to be spoken at this point, the most logical starting place for the Stranger would be alongside the entry of the organ (see Example 2). If this was the case, then the Stranger’s entry – along with the organ part – would sound as the onset of a new section within the musical structure. That the voice is treated in this way only accentuates its instrumental qualities, entering as a new timbre alongside the organ. Additionally, Rangström also scores a break at the Lady’s entry, shifting from a B minor to D minor seventh chord when the Stranger says ‘The sun!’ (‘Solen!’), underscored by a tremolo in the strings and piano (see Example 3). This tremolo is surrounded by sequential developments of the opening motif such that, on the page, the introduction of this new material stands out as a structural break. The shimmering, ethereal sound of the strings and piano evokes the change in atmosphere as the light changes, succeeded by a tempo acceleration (from Andante con moto to Allegro) and motivic diminution as the Stranger’s imaginings become more animated, Rangström’s score matching Strindberg’s temporal shift.

Example 2 Ture Rangström, music for Till Damaskus (III), Cue 4, bars 17–19.

Example 3 Ture Rangström, music for Till Damaskus (III), Cue 4, bars 24–7.

This cue was one of those used for the 2015 reflexive performance, and demonstrated for me as an analyst how quickly perception can shift from a focus on qualified media to a more sensorial mode. I came to the performance with the intention of focusing specifically on qualified media – I had been studying Rangström’s music for several months, had produced a performable edition of the cue and had a set of analytical questions centred on the music that I wanted to explore through the performance. I had read through the monologue aloud, accompanying myself at the piano with my own arrangement of the score, and knew how I expected the music to sound. My expectations and prior experience made me much more focused on qualified media than any audience member could reasonably be assumed to be. Even so, when placed in the position of spectator, experiencing the actor performing the monologue with the full instrumentation, I did not find myself delineating between qualified media.Footnote 101 I heard voice and music as integrated, and the visual impact of the actor moving around the chapel and incorporating gestures gave continuity to moments in the music that I had previously thought of as being structural breaks. When the music is heard on its own, the aforementioned chord shift from B minor to D minor at ‘Solen!’, for example, sounds like a significant shift in musical direction, and indeed somewhat confused the performers when we played it through without the text. When performed with onstage action, however, with the actor’s gestures contributing continuity, the whole group agreed that this moment seemed now to provide a slight shift in mood, rather than the disjuncture that was so extreme it seemed disorientating on its own.

At least part of my shift in focus away from qualified media was due to how the actor spoke their lines. The first time we read through the passage, without having heard the music, the actor spoke relatively quickly and without large variations in vocal pitch. When asked to give the speech alongside the music, however, he found himself changing his vocal delivery to feel that his speech ‘fitted’ the music. With the music, he spoke with a broader range of both pitches and dynamics, not least because he had to put in more effort to be heard over the instruments. This resulted in the kind of operatic declamation which Hesselager describes as ‘physical and embodied in a radical way’, intimately connecting gesture, voice and music.Footnote 102

Here, reflexive performance leads us back to the 1926 production. Hearing this scene performed helped to contextualize Lindberg’s own writings about vocal delivery, and the way that actors’ voices were discussed by critics. In his book Regiproblem (‘Directing Problems’), Lindberg commented at length about the sound of actors’ voices, and how this related to debates about modern theatre. He explained that realism produced styles of declamation that were rooted in ‘observation, reproduction, real accuracy’. However, he wanted a style of delivery that was more highly stylized, cultivating a more expansive attitude towards voice and gesture, moving away from accuracy and towards ‘beauty, expression, technical skills, artistic generosity and elevation’.Footnote 103 Alongside spectacular sets and the inclusion of an extensive musical score, stylized, ‘unrealistic’ vocal declamation was a critical facet of the modern sound of Lindberg’s productions.

Correspondingly, reviewers frequently commented on the timbral qualities of individual actors in Lindberg’s productions, including Till Damaskus. Olof Sandborg, who played the Stranger, was criticized precisely because his voice lacked ‘any major possibility for nuance’, and therefore ‘the really enlivening spark was missing’.Footnote 104 His ‘chanting declamation’, wrote another, ‘seemed to be filled with air instead of fire and blood’.Footnote 105 Nils Ahren as the Confessor, however, was praised for his sonorous voice that ‘really harmonized’ with the organ.Footnote 106 But the actor whose voice attracted most commentary was the Norwegian guest star, Ingolf Schanche, as the Tempter. As a Norwegian actor in a Swedish production, Schanche’s accent would already have differentiated him from the rest of the performers: Göran Lindblad for Svenska Dagbladet stated that Schanche’s Norwegian accent and ‘dry laughter’ helped give the ‘impression of diabolical brilliance and worldliness’,Footnote 107 while others described his voice as ‘sharp and hollow’,Footnote 108 his words delivered with a ‘surgical precision’.Footnote 109 In theatre as much as in opera, ‘individual “voices”’, as opposed to ‘“voice” in the epistemological abstract’, articulate a ‘sonic expression of unique identity and experience’, becoming theatrical signs and contributing to the creation and perception of meaning within a production.Footnote 110

Gender in Till Damaskus (III)

Critics generally agreed that the production combined two main moods. One was ‘ironic’ and ‘sarcastic’, with Eve’s trial for original sin singled out for praise, described in one of the more analytically detailed reviews as a ‘truthful caricature about justice on earth’.Footnote 111 The other mood was ‘pious and naive’, best represented by the scenes with the Lady who was played by Strindberg’s former wife, Harriet Bosse.Footnote 112 Reading through these reviews, I was particularly surprised at the critics’ verdict on the gender dynamics in the production. In Strindberg’s script, the Lady is both seducer and salvation in her roles as wife and mother, respectively. In one of the play’s most formative scenes, she is transformed on stage into the Stranger’s mother before vanishing, and it is this transformation that prompts the Stranger to delay his journey to the monastery to try to find happiness on earth by remarrying the Lady. Strindberg had been an outspoken and divisive voice on the ‘woman question’ in turn-of-the-century Sweden, and the portrayal of motherhood as a redemptive role for women was commonplace in his plays. Even in his own lifetime, Strindberg’s views about women were both reactionary and conservative. As Margaretha Fahlgren writes, ‘The traditional male ideals which Strindberg maintained represent the hegemonic masculinity of the late nineteenth century’; this contrasts with Ibsen, whose portrayals of women were ‘much more in line with the modern emancipation movement’.Footnote 113

If Strindberg’s views on women were somewhat outmoded in 1904, they certainly should have been much more so in 1926. The 1920s saw ‘an intensified quest for equality’, with various laws and reforms introduced that aimed to improve women’s societal and economic independence.Footnote 114 Women were also occupying increasingly prominent positions in Swedish society: Selma Lagerlöf had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1909; the first women were elected to Swedish parliament in the 1921 election after the introduction of women’s suffrage in 1919; and in 1923 Behörighetslagen (‘The Competence Act’) was passed, decreeing that women could work in all professions, with some religious and military exceptions. The terms of debate about women’s position in society had shifted immeasurably between 1904 and 1926.

This was the historical context that I had in mind when I began analysing the impact of Rangström’s music on Strindberg’s script. Aiming to understand how the Lady might have been portrayed in the production, I focused on the moment when she transforms into the Stranger’s mother, which Rangström underscored as cue 13. The transformation is preceded by a debate between the Lady and the Tempter, as they battle for the Stranger’s soul. Rangström sets the opening lines to an imitative organ passage, which is then adopted by the violins, as the Lady and Tempter argue with each other (see Example 4). When the Lady seems to be winning the argument, Rangström passes the motif to the piano, played at double speed against a string tremolo. This exchange between organ, strings and piano continues until the Lady changes tactic and moves from philosophical debate with the Tempter to a direct emotional appeal to the Stranger, imploring him to listen to her as the mother of his child and, later, as the Stranger’s own mother. Where the stage direction reads that she ‘falls to her knees with clasped hands’ to begin her appeal, the music suddenly changes to a lullaby in D♭ major. The piano provides a lilting bass line rocking between tonic and dominant, while the strings play a melody loosely based on the cue’s opening motif (see Example 5).

Example 4 Ture Rangström, music for Till Damaskus (III), Cue 13, bars 1–12.

Example 5 Ture Rangström, music for Till Damaskus (III), Cue 13, bars 63–9.