Introduction

The main goal of every democratic government is to fulfil the electoral pledges it made to voters. Statutory legislation (laws, acts of parliament) represents the dominant instrument for shaping public policies. The executive is the key legislative actor in all parliamentary democracies: it is responsible for submitting the majority of bills (drafts of laws/statutes) to parliament, and almost all government bills are successfully adopted into law (Schwarz and Shaw Reference Schwarz and Shaw1976; Olson and Norton Reference Olson and Norton2007; Saiegh Reference Saiegh2009). While this framework functions smoothly in Westminster systems with a tradition of single-party majority governments, the process is less straightforward in proportional parliamentary democracies where coalition governments are the norm. In coalition governments, the executives face numerous challenges associated with the fact that their government is composed of political parties that often compete for the same voters yet differ in ideology and in their political programmes. Coalition parties must attempt to enforce their political priorities and also resolve any conflict before a bill is agreed upon and becomes law (see review in Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin, Vanberg, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014a).

The state-of-the-art in research analysing the intra-coalition dynamics has evolved around the “keeping tabs” thesis. It is being argued that while ministers have the motivation to pursue independent policy choices favourable to their parties, other coalition parties try to control this ministerial drift and sway the outcomes of legislation to accommodate their interests. Coalition governments thus need to tackle the problem of how to ensure the effective and balanced mutual control of ministers (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b; Müller and Meyer, Reference Müller and Meyer2010; André et al. Reference André, Depauw and Shane2016; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020). Empirical testing indicates coalition partners prefer a consensual approach and resolution of mutual controversies. Numerous studies reveal that the first versions of government bills are amended significantly during the law-making in legislatures and the studies link the changes to intra-coalition bargaining (Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Brunner Reference Brunner2013; Pedrazzani and Zucchini Reference Pedrazzani and Zucchini2013; Indridason and Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2018; Dixon and Jones Reference Dixon and Jones2019; Gava et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021).

While the research into the keeping tabs thesis is well-established and persuasive, its limitation lies in the almost exclusive empirical linkage with the parliamentary phase of law-making. The puzzle remains as to what happens before the bill is officially submitted to the legislature. Before that moment, most government bills must undergo an extensive formalised process between the tabling of the first version of the draft by the responsible ministry and its adoption by the government. During this drafting and negotiating phase, one may expect that the coalition parties will also engage in mutual control and seek to settle potential disputes in shaping public policies through statutory legislation. In practice, the keeping tabs strategy is even more rational and effective in the early stages of law-making as it usually takes place out of public view and without the interference of the opposition. Although some scholars have pointed to the importance of the stated research puzzle (e.g. Gava et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021), existing studies have unfortunately not addressed it.

The aim of our study is to shed light on this proverbial dark corner of policy-making and investigate if and possibly how the coalition parties control one another during the executive phase of law-making. In line with the keeping tabs argument, we expect that factors determining the political positions of the involved subjects concerning the drafted legislation will have an impact on the ratio of changes to the bills. The proposed theoretical framework is tested quantitatively on a unique dataset covering changes to more than four hundred government bills entering the executive phase in the Czech Republic between 2010 and 2016. The Czech case serves as the prototypical representative of a (quite large) group of states with a tradition of coalition governments and a formally regulated process of the executive phase of law-making.

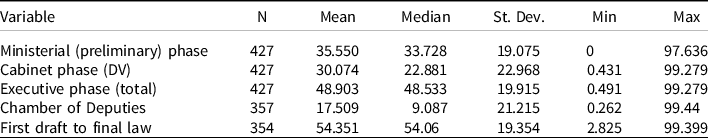

The importance of focus on the executive phase is validated empirically in the presented data: the median change to bills during this stage of law-making in the Czech Republic is 22 per cent, more than double the subsequent alteration of bills in the parliament (9 per cent, see Table 1 below for details). The keeping tabs thesis is only partly confirmed. While we find no significant impact of the distance to coalition compromise, the saliency of the bill to coalition partners has a negative influence on the ratio of changes. Also, contrary to our expectations, the “preprocessing” of bills by the initiating ministry leads to more amendments in the cabinet phase. Closer analysis of the interaction of analysed key factors however reveals that executive law-making defies simplified findings. Technical factors (controls) also affect how much the bills are amended.

Table 1. Changes to bills in different phases of the legislative process (in per cent)

Note: Our own coding from the VeKLEP database and the database of the Chamber (see Online Appendix). Only government bills introduced by the Nečas and Sobotka governments are included. Drafts that were terminated in the cabinet phase are excluded. The number of bills in the Chamber is reduced because some government bills failed in the parliamentary phase of the legislative process.

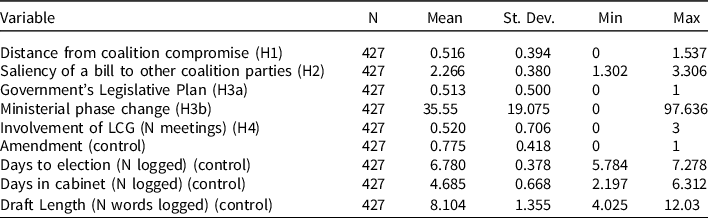

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Note: Table for standardised variables used in the regression model in online appendix (Table B).

The article is structured as follows: The first section debates the theoretical framework of mutual control in coalition governments in the executive phase of law-making and formulates our hypotheses. The next part briefly describes the determinants of the Czech case and its relevance for a broader set of cases. The subsequent section presents the research design and methodology, including model specifications and dataset. The penultimate section lists and discusses empirical results and offers alternative explanations for unanticipated outcomes. The last section presents conclusions and makes suggestions for further research.

Factors of a political nature affecting changes of bills in the executive phase

The initial versions of proposed bills are often amended during the legislative process. Some of the alterations are of a technical nature (e.g. correction of language mistakes), while the more research-worthy changes are those driven by political causes. No one questions the prominent position of executives in law-making and the creation of public policies (also Rasch and Tsebelis Reference Rasch and Tsebelis2010). The majority of governments in parliamentary democracies are coalition cabinets (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair2011: 434), and they face several distinct challenges during the law-making process. First, because the coalition is composed of various political parties, there is a classical principal-agent problem where the principal is the collective government and the agents are the ministers from coalition partners that command their ministries. The positions of the ministers may differ from the government’s position, i.e. the ideal coalition compromise. Ministers often pursue their own policy goals to appeal to their party members and voters. This ministerial drift may originate from various factors – coalition parties have different bargaining power depending on their proportion of seats in the executive or parliament; they also pursue diverging policy interests or disagree on the saliency of many issues (see Müller and Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Torbjörn2008; Müller and Meyer, Reference Müller and Meyer2010). Second, there is the question of unequal positions of ministers from one political party vis-a-vis other coalition parties, because the former holds a particular advantage over the latter in terms of information availability and competence of drafting the bill in relevant policy field (Thies Reference Thies2001). Ministers can collaborate with their ministry´s bureaucrats who have the resources and expertise to draft legislation and become acquainted with the necessary technical details (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair2011). For policy-seeking parties, such settings endanger their influence on public policy, which in turn reduces the policy benefits of being in office (Krauss Reference Krauss2018).

Two general models were proposed to solve the described obstacles. Initial inquiries into coalition governance assumed simple circumvention of the drift threat. The so-called ministerial discretion model grants each coalition party autonomous rights over the assigned ministerial portfolio and allows them to treat it as their “fiefdoms” (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). But later studies challenged the argument, “at least in a fully-blown version” (Müller and Meyer Reference Müller and Meyer2010: 1067). The collective responsibility model, based on the veto players theory, suggests instead that the consent of each coalition member is required for the adoption of a bill and the final outcome stems from coalition deliberation and bargaining (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). The more the policy preferences of the coalition parties differ, the more control mechanisms are required to counter drift. The crucial goal of the coalition government is thus to make the ministers adhere to coalition goals instead of serving their party. Research has identified a broad array of mainly institutional instruments designed to avoid the threat of agency loss that may cause changes to the initial version of a bill proposed by a minister. Most of these instruments were explored in the parliamentary phase of law-making that functions as the ultimate form of control within a coalition (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020; André et al., Reference André, Depauw and Shane2016; Höhmann and Sieberer, Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020).

Our analysis adheres to propositions of the collective responsibility model and extends it to the executive phase of law-making. During the period between the presentation of the initial version of a bill by the ministry and its adoption by the government, the coalition partners have opportunities to identify possible ministerial drifts, resolve outstanding differences in positions, and change the bill in order to move the output close to a common coalition compromise. One may even claim that the coalition motivation to keep tabs is stronger during the executive phase than the parliamentary one. There is no rational explanation why a government would submit a bill to the legislature that will be defeated (Shepsle Reference Shepsle2010), and there is little logic in making the government vulnerable by submitting a bill over which a coalition war will be waged in the open parliamentary arena. Scholars have indeed identified several instruments that may theoretically serve for mutual coalition control in the executive phase, for example, inter-ministerial consultations, appointment of junior ministers to ministries held by other political parties (Thies Reference Thies2001; Lipsmeyer and Pierce Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011), binding coalition agreements (Indridason and Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013; Krauss Reference Krauss2018), or the establishment of special (informal) coalition committees (Andeweg and Timmermans Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Ström, Müller and Bergman2008). Also, the drafting of a bill is carried out by professionals with long experience, which should ensure that the policy intent of politicians is faithfully reproduced in the legislative language and has no legal flaws (Dixon and Jones, Reference Dixon and Jones2019). All these factors support the relevance of the keeping tabs argument in the executive phase.

Naturally, if coalition conflict occurs and how that impacts bills depends on numerous conditions. One of the most significant factors in studying coalition government law-making is the position of coalition parties on the policy that is being targeted by the legislation in question. Similarly to Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2004: 18), we anticipate that the more distant from a coalition compromise the position of a political party is to a bill submitted by “its” ministry, the higher the likelihood is that the bill will be altered in order to accommodate the diverging political interests of coalition partners. Even if the political parties have incomplete information on other actors’ preferences and the effects of laws (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1991; Thies Reference Thies2001), and there is an informational advantage for the drafting ministry (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair2011), the efforts to reach consensus presuppose the association of the changes to a bill with policy positioning:

H1: The greater the policy distance on a bill between the political party holding the ministry submitting the bill and the coalition compromise, the more changes the bill undergoes in the executive phase.

Public policies (and ensuing bills) have different levels of importance to each political party, and members of a coalition are usually assigned ministerial portfolios corresponding to their political priorities (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011). This finding is based on the salience theory of party competition, which suggests that parties try to focus on the issues that are advantageous to them rather than compete for an agenda preferred by other parties (McDonald and Budge Reference McDonald and Budge2005). Saliency as a predictor of bills’ changes has two sides of the coin: the first is the saliency for the proposing minister (and his/her party), and the other is the saliency for the coalition partners. In line with the keeping tabs thesis, the latter has a more pronounced effect, because the higher saliency means the higher motivation to counter ministerial drift (Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020).

H2: The higher the saliency of a bill to other coalition parties (than the party holding the ministry submitting the bill), the more changes the bill undergoes in the executive phase.

One of the most problematic aspects of testing the mutual control within the coalition is the potential application of an anticipation strategy by the proposing subjects. The low level of observed changes in a bill may not necessarily mean that there were no conflicts to settle among the coalition partners, but it could mean that the proposing ministry correctly identified any conflicts and adapted the proposal accordingly prior to its presentation. Gava et al. (Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021: 188) refer to this situation as “the problem of observational equivalence.” Our inquiry into the executive phase in principle targets the issue as it is based on an expectation that government bills were changed before they were submitted to the legislature. Yet such an anticipation strategy might be utilised even before the bill is submitted to the executive phase. Methodologically, it is very difficult to test theoretical propositions that result in zero variety in the dependent variable (no changes in bills), but some indications may point to the application of the anticipation strategy.

As noted above, coalition parties traditionally adopt coalition agreements that define the priorities of the government in key aspects of policy-making. In some states, the planned legislative agenda forms part of such agreements; in other countries, the governments even publish a catalogue of concrete bills which it aims to submit to the legislature and that would implement coalition pledges (Zubek and Klüver Reference Zubek and Klüver2015). We expect that the listing of a bill in such a document would imply that there is already an existing consensus among the members of the coalition on at least the basic features of the bill’s content.

H3a: If the government bill is listed in the document that presents the priorities of the coalition government, the bill undergoes less changes in the executive phase.

While the moments of adoption of a bill by the government or its submission to the legislature are easy to determine, the starting point of the executive phase, i.e. the official publication of the initial version of the bill by the ministry, is more fluid. If the minister is concerned about potential conflicts, he/she may opt for prior consultations with the coalition partners or other actors. In many countries, there are either informal or formal instruments, such as inter-ministerial consultations, that enables to receive objections to the draft bill and to adapt the text before it enters the executive phase (Albanesi Reference Albanesi2020). From a practical viewpoint, it is also easier to accommodate the interests of others during the earliest stages of forming a consensus (Raiffa Reference Raiffa1985). We assume that a diligent implementation of demands at the beginning by the ministry reduces the need for changes later on.

H3b: The more the initiating ministry changes the government bill before it officially enters the executive phase, the fewer changes the bill undergoes in the executive phase.

Enforcement of their own (subjective) political interests is not the only goal of coalition parties during the drafting of legislation. They also strive to propose bills that objectively have the desired impact and are of high legal quality. In the last several decades, these efforts for “better regulation” have permeated the legislative process in almost all democratic states. The implementation of the agenda is usually assured by special institutions set up within the executive, and they may scrutinise the proposed bills for deficiencies (for EU states see review in OECD 2019; Howlett Reference Howlett2019). While most of these bodies are composed of independent experts or civil servants and are thus free from direct political pressures, their recommendations on how to amend the bill might either retrospectively mirror the political conflicts (e.g. by overlapping with the interests of a coalition party) or be prospectively exploited by a member of the coalition to set the new demands for changes to the bill.

H4: The more closely a government bill is scrutinised by institutions reviewing its regulatory and legal quality, the more changes the bill undergoes in the executive phase.

Determinants of the Czech executive law-making and prototypical character of the Czech case

The Czech Republic represents a classic parliamentary political system (Brunclík and Kubát Reference Brunclík and Kubát2016). The bicameral parliament consists of two chambers; the parliamentary law-making occurs primarily in the Chamber of Deputies to which the executive is responsible through a positive investiture vote. The government is by far the most important force in the legislative process and accounts for 60 to 70 per cent of bills submitted to the Chamber, and about 80 per cent of those are successfully adopted into law.Footnote 1 The most important or complex bills are almost always initiated by the executive. Because elections to the Chamber are based on the proportional system, governments have always been coalitions. Because the coalitions are usually ideologically diverse and command only a minimal majority in the Chamber, the intra-coalition relations are often terse (Deegan-Krause and Haughton Reference Deegan-Krause and Haughton2010). The motivation for keeping tabs on coalition partners under these circumstances is high.

The process of a bill’s drafting and negotiation in the executive phase is quite formalised and regulated by the Legislative Rules of the GovernmentFootnote 2 and can be divided into two stages. We label the initial one the “ministerial phase,” and it starts with the release of the preliminary version of the bill. The text is drafted by the ministry; the choice of ministry is mostly determined by the policy field which the bill (predominantly) regulates. The bill then enters the inter-ministerial consultations, and all ministries are invited to send comments related to the bill. During this procedure, from a few dozen to thousands of comments are regularly registered. The drafting ministry reviews the comments and implements them at its will. The phase ends with the publication of the redrafted bill by the initiating ministry, and the bill is officially presented to the government.

During the second stage (further labelled as “cabinet phase”), the current version of the bill is scrutinised by the Legislative Council of the Government (LCG) and its working groups; independent bodies staffed mostly by experts and civil servants. The objective of the LCG is to ensure that a bill meets the regulatory and legal quality of “good legislation.” Bills are either scrutinised by the chairman of the LCG (a politician with the rank of minister) together with his/her administrative support or discussed at full LCG meetings. In both cases, the LCG publishes a report with recommendations on how to adapt the text of the bill (Filip Reference Filip2007). However, the main responsibility for the bill remains with the submitting ministry. Simultaneously with the review by LCG and even after its report is released, the ministry still has the discretion to react to any outstanding or new comments or disagreements from any subjects, including other ministries, and is entitled to freely amend the bill. Once the responsible ministry deems the content and backing for the bill sufficient, it puts the bill on the agenda of a cabinet meeting where a majority vote of all ministers is required for its adoption.Footnote 3 If this is not the case, the cabinet is also entitled to reject the bill (which happens extremely rarely) or return it to the negotiating process. Successfully adopted bills are forwarded to the Chamber.

The Czech Republic was selected for analysis for two reasons. The practical advantage is the unusually transparent proceedings of the executive phase of law-making, permitting the collection of unique data necessary for testing the presented theoretical framework. Yet despite the inherent limitation of single case studies, the Czech case is also valuable because it may serve as a prototypical case featuring many important characteristics that are found in a large number of other cases (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2014). As noted above, theoretical determinants of intra-coalition dynamics work similarly in most parliamentary proportional democracies. The question, of course, arises about the differences in institutional frameworks and proceedings of the executive phase of law-making. It is fair to admit that the legislative processes in almost all countries evince various local specifics (e.g. in the level of coordination and interference by the prime minister), but at least states in Continental Europe share the fundamental attributes defining the executive phase. Most of all, they apply the ministerial model where it is the submitting ministry that is responsible for drafting the bill and its guidance to the legislature (Albanesi Reference Albanesi2020). Instruments enabling mutual coalition control in the executive phase, such as inter-ministerial consultations, independent scrutiny bodies, or coalition priority agreements are commonly used across Continental Europe in the executive phase of law-making (OECD 2019, see detailed description of the formal framework in Poland, Slovakia or Austria in Zbíral Reference Zbíral2020 or Maasen Reference Maasen, Kluth and Krings2014 for Germany). Hence, the findings of this article might also be generally applicable for these political systems.

Research design, data, and methods

We employ a quantitative approach in testing the factors associated with the changes to bills in the executive phase. The analysis covers the period starting after the 2010 elections to the Chamber until the end of 2016. The beginning of the time span is determined by data availability; the publicly accessible database of the executive phase of law-making (VeKLEP) became operational in 2009.Footnote 4 Two political coalition governments were formed during the interval, one centre-right headed by prime minister Petr Nečas, followed by the centre-left government of Bohuslav Sobotka (see Online Appendix Table D, E and F). While there were significant developments within the Czech political and party systems during the given period (Havlík and Voda Reference Havlík and Voda2016), the formal institutional framework on drafting and negotiating bills in the executive (see previous section) remained stable. To avoid the problem of missing values, only the bills that were successfully adopted by the government and thus finalised in the executive phase were included. In total, 427 cases (bills) were entered into the analysis.

As presented above, due to two stages of the executive phase, three iterations of a bill are at our disposal (tentative version of the bill’s draft, official version of the bill’s draft, final version of the bill). Normally, the ratio of change between the first and last versions of bills would be used, but instead we decided to base the analysis on the amount of a bills’ amendments during the cabinet phase. This option reflects the view that ministerial and cabinet stages are rather distinct. The former has a mostly preparatory character with a focus on elimination of mistakes or inconsistencies and is under the complete control of the initiating ministry. Only in the latter phase, when the bill is officially introduced to the government, do high-level interests become more involved – use of data from the cabinet phase thus better mirrors our goal of testing the influence of mutual political control in the coalition. Nevertheless, the changes to a bill in the ministerial phase are used as a predictor of changes in the cabinet phase (see H3b, the model for the ministerial stage is in the Online Appendix under Table C).

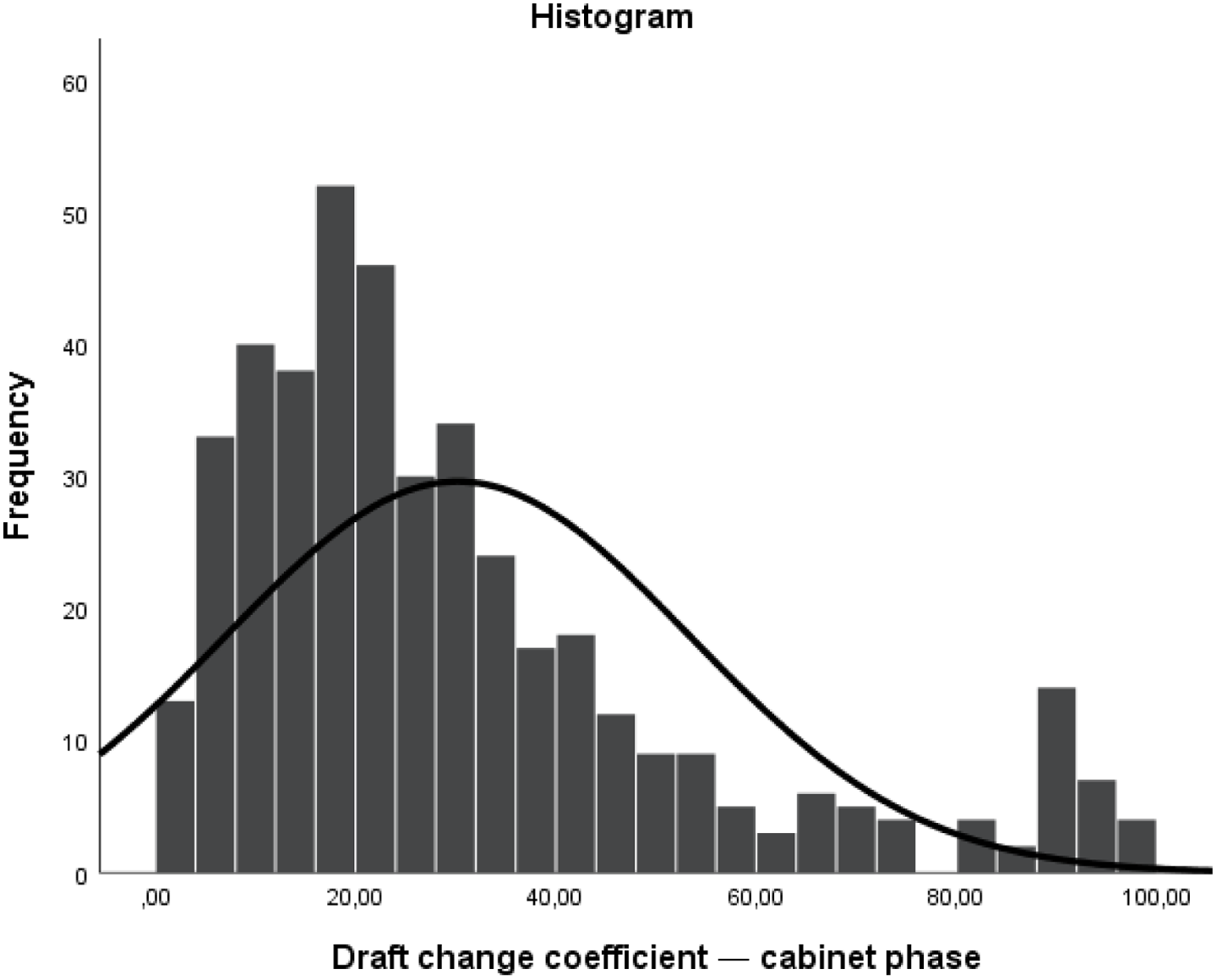

Figure 1 Distribution of values - draft change coefficient for the cabinet phase.

Dependent variable and model specifications

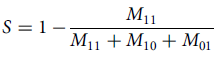

The dependent variable (DV), the degree to which a bill is changed, is measured through an automated quantitative text analysis based on word counts, which we preferred to other options such as counting the number of amendments (Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011) or a qualitative hand-coding assessment of a bill’s changes. We build on the measurement of change as proposed by other authors (Pedrazzani and Zucchini Reference Pedrazzani and Zucchini2013; Indridason and Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2018; Casas et al. Reference Casas, Denny and Wilkerson2020; Gava et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021) who enquire as to how many words were added, deleted, and modified in a bill. Differently put, we look at the similarity of the text. The DV is expressed as a change coefficient ranging from the value of 0 (no change) to 100 (the bill is unrecognisable from its original) and was computed by text comparison between a bill as officially submitted to government and the bill as adopted by the government (see above). All downloaded bills were converted to txt files with unified encoding (utf-8), texts were tokenised into single words, and punctuation marks and numbers were removed. All words were transformed into lowercase and then transformed into continuous bi-grams. Our approach generally followed operationalisation in Gava et al. (Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021). However, we did not remove headers or footers from the bills because they are relevant in the Czech context, particularly in the case of amendments to already existing laws. Such preprocessed texts are suitable for measuring distances by the Jaccard dissimilarity index S, which understands the bills as sets:

$$S = 1 - {{{M_{11}}} \over {{M_{11}} + {M_{10}} + {M_{01}}}}$$

$$S = 1 - {{{M_{11}}} \over {{M_{11}} + {M_{10}} + {M_{01}}}}$$

where

![]() ${M_{11}}$

is the number of shared bi-gram words in both texts,

${M_{11}}$

is the number of shared bi-gram words in both texts,

![]() ${M_{10}}$

is the number of bi-grams present exclusively in first text, and

${M_{10}}$

is the number of bi-grams present exclusively in first text, and

![]() ${M_{01}}$

is the number of bi-grams exclusively present in the second text. The script is publicly available (see Online Appendix). To validate our approach, we have computed the index using simple uni-grams and we present the results for both approaches in the Online Appendix (Supporting Material CH). Furthermore, we have randomly selected 100 bill pairs and let coders decide on the scale 1 (no change) to 5 (complete change). The correlation between human coding and automated text analysis is high (R = 0.76, p < 0.05). The major drawback of an approach based on word count is that the quantitative degree of change does not necessarily relate to the quality (substance) of change – obviously only qualitative methods can overcome this issue.

${M_{01}}$

is the number of bi-grams exclusively present in the second text. The script is publicly available (see Online Appendix). To validate our approach, we have computed the index using simple uni-grams and we present the results for both approaches in the Online Appendix (Supporting Material CH). Furthermore, we have randomly selected 100 bill pairs and let coders decide on the scale 1 (no change) to 5 (complete change). The correlation between human coding and automated text analysis is high (R = 0.76, p < 0.05). The major drawback of an approach based on word count is that the quantitative degree of change does not necessarily relate to the quality (substance) of change – obviously only qualitative methods can overcome this issue.

The actual distribution of the DV is skewed, and the mean value is biased by extreme positive values. The median is one-third the size of the mean (see Figure 1). The majority of bills were changed moderately, but a significant number of bills were almost completely altered during the executive phase. We use the Poisson regression model because the data are not sufficiently overdispersed to justify the use of negative binomial regression (the dispersion parameter, alpha, is negative). As control models, we have transformed the DV into the ratio dividing the index by 100, and we have run a simple logistic regression and zero one inflated beta regression models for proportional data (see Online Appendix Table C).

Exploratory analysis showed that the differences in the average number of changes to bills in the cabinet phase between the Nečas and the Sobotka governments were not statistically significant (t-test). Likewise, the average number of changes to bills does not differ across initiating ministries in the two coalition governments, and this is mirrored in the zero value of the intra-class correlation coefficient obtained from the null model when specified with a random intercept (or simple ANOVA). This suggests that there is no need to model data as hierarchically clustered by ministries. Still, we use control dummy variables for ministerial portfolios to avoid confoundedness, as some predictors may be correlated with specific portfolios, and also to limit the omitted variable bias. The policy field of bills are also included in the model as control variables because some may be inherently associated with higher changes and also with selected predictors. Due to the complexity of the data and possible model choices, we refer to the online code, other control models and robustness checks, and the further information provided in the Online Appendix.

To put the presentation of values of DV into perspective, we also calculated the ratio of changes in bills for other stages of the legislative process than the cabinet phase (see the descriptive statistics in Table 1). The averages (both median and mean) of changes in the initial phases of law-making are considerably higher than in the subsequent parliamentary (Chamber) phase, validating the importance of our research agenda. The bills undergo significant changes in the ministerial and cabinet stages, yet the sum of both phases does not equal the total alterations during the whole executive phase. In practice, it means that some provisions that are changed at the beginning may later have their original wording reinstated.

Independent variables

The independent variables (IV) measuring the political factors in our hypotheses are coded as follows (see the descriptive statistics in Table 2). To account for the policy distance of the proposing ministry (political party) from the coalition compromise (H1) and the saliency of a bill for the other coalition parties (H2), we have used the Chapel Hill (CHES) dataset that measures the saliency of an issue and policy position of a party through an expert survey (Polk et al. Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017). Each bill was manually assigned to one of the several Chapel Hill survey categories (civlib_laworder, deregulation, environment, redistribution, regions, urban_rural, social lifestyle, spendvtax). For the parties’ distance from coalition compromise, we followed the operationalisation developed by Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b) that computes the absolute distance between the policy position of the party of the proposing minister on the relevant policy dimension and the coalition compromise position. The compromise position on the associated issue dimension is “the seat-weighted average of the policy positions of the government parties” (ibid: 986). The saliency of a policy field reflects the values from the CHES dataset and expresses the mean value for nonsubmitting coalition parties. We assigned the values to a bill and not the ministries because not all bills from certain policy fields are always initiated by the relevant ministry (e.g. some bills related to industry may be drafted by the Ministry of the Environment and not by the Ministry of Industry and Trade).

The potential application of the anticipation strategy by the proposing ministry is tested with two variables. The existence of a preagreement by the coalition parties on a bill (H3a) is measured by the inclusion of the bill in the Government’s Legislative Plan (GLP) (dummy). GLP provides a list of bills that the ministries plan to submit to the executive phase each year and is generally built on the coalition agreement and objectives of the executive for the election period. The extent of preliminary adaption of a bill by the proposing ministry (H3b) is observed through the ratio of changes the bill undergoes in the ministerial phase. An explanation for the logic of the measure and the character of that stage was already provided. The variable was calculated by the same approach as DV and computes the difference between the preliminary version of a bill and the official version submitted to the cabinet phase. Finally, the level of involvement of the independent scrutiny body (H4) is expressed by the number of times a bill was on the agenda of LCG meetings.

Control variables (technical factors) and limitations

Factors covered by our theoretical framework focusing on mutual control in the coalition government are not the only reasons why bills are changed. We added several variables to the model in order to control for other possibly influential drivers (see the descriptive statistics in Table 2).

At the statutory level, changes in legal order are implemented through two types of bills that are formally of the same legal value yet differ in practice. The first is a self-standing new bill, either aimed at the regulation of a so-far unregulated sector (e.g. the operation of autonomous vehicles) or the complete redrafting of (an) existing bill(s) (e.g. the recodification of the labour code). The second category of bills is the so-called amendments that change already existing laws. Of course, even these could be rather extensive, for instance, a new, long section can be added, but amendments are, by their nature, linked to the “mother” law. The former group of bills is better arranged for scrutiny (one does not have to know the mother law) and generally attracts more interest from stakeholders (Dixon and Jones Reference Dixon and Jones2019). Therefore, we included a control dummy variable if a bill was an amendment.

As almost all preceding studies controlled for the number of words of a bill and associated longer bills with fewer changes (e.g. Gava et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021), we add the variable to the model (logged). The degree of change may be also correlated with the duration for which a bill is negotiated. Bills that stay in the executive phase longer probably face difficulties and tend to have more alterations. The variable is coded as the number of days a bill spent in the cabinet phase (logged).

The timing of a bill’s initiation may also be of importance. Researchers exploring the issue on data from parliaments indicate that the closer to an election, the fewer changes bills undergo. They argue that mutual scrutiny is more intensive when the coalition is freshly formed (Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020) and that politicians concentrate more on campaigning when there are looming elections (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b; Gava et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021). We do not classify this driver as a political one because it is forced on the legislative actors by the election cycle. A late submission usually does not stem from a deliberate political choice; the risk of delay or failure of the bill would be too high. In the model, we included the number of days to an election (logged) from the date a bill was officially submitted by the ministry to the government.

Studies focusing on changes to bills in the parliamentary phase include other variables in their models (Pedrazzani and Zucchini Reference Pedrazzani and Zucchini2013; Indridason and Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2018; Gava, et al. Reference Gava, Jaquet and Sciariny2021). Some are limited to legislatures (e.g. party affiliations of committee chairs), while a few do not fit the Czech case. The most notable of these is the seemingly high impact of a vice-minister (junior minister) from the coalition party that scrutinises ministers from the other coalition party (Thies Reference Thies2001; Lipsmeyer and Pierce Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011). Yet each Czech ministry traditionally employs numerous vice-ministers (náměstek), and almost all coalition partners consequently have the opportunity to assign at least one vice-minister to those ministries. Because eventually all parties virtually control one another through this instrument, the variable would gain a constant value and be useless in variance-based research design. We stress that we do not exclude the possibility of the effect at all, but a qualitative approach would be needed to investigate the role of vice-ministers (e.g. to assess and differentiate the real influence of each vice-minister).

Results and discussion

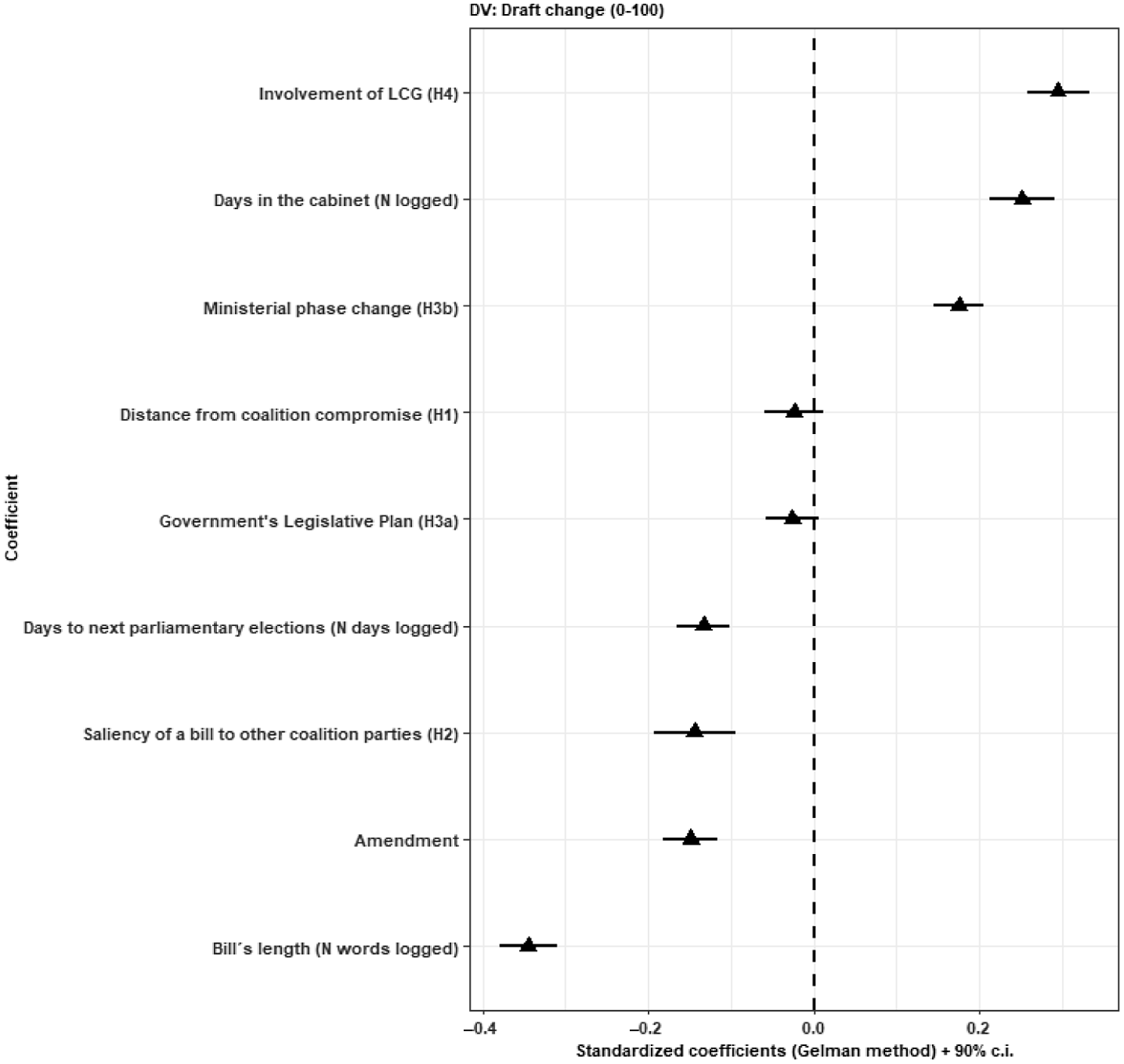

The main objective of our analysis is to test the theoretical determinants of the keeping tabs thesis in the executive phase of law-making. Figure 2 shows the results of the applied Poisson regression model for the cabinet phase (see above), visualised utilising the coefficient plot where the points represent the estimates and the lines express the 90 per cent confidence interval. The variables are standardised by the Gelman (Reference Gelman2008) method by two standard deviations (2SD) for ease of interpretation, and the resulting coefficients are directly comparable to binary predictors, because a 2SD change corresponds to a change from 0 to 1, approximately from minimum to maximum value of IV in Table 2. This change is associated with the change in the DV, holding all other IV constant, by a coefficient value. Table presentation, alternative specifications, and robustness checks are provided in the supplementary Online Appendix (Table C).

Figure 2 Changes to bills in the cabinet phase (main model).

Note: Poisson regression models. Variables are ordered by coefficient magnitude. Control dummies: Ministerial portfolios, Chapel Hill categories and policy categories as defined in VeKLEP (not displayed). Nonindicator variables scaled by dividing two standard deviations (Gelman Reference Gelman2008). Model Cabinet phase Pseudo-R2 = 0.161, Null deviance = 6661.4, Residual deviance = 4803.4, N = 427 (alternatively, see Table A in the Online Appendix). “Coefplot” package in R.

Overall, the model indicates the importance of political factors for the executive phase of the legislative process, yet the anticipated correlations drawn from the research on parliamentary data are not always validated. The impact of the distance of the proposing ministry (political party) of a bill from a coalition compromise (H1) serves as a case in point because the (self-standing) variable has no impact on the ratio of a bill’s changes. A possible explanation might lie in the low validity of the variable’s operationalisation, a problem that also seems to appear in previous studies (Goetz and Zubek Reference Goetz and Zubek2007; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b; Zubek and Klüver Reference Zubek and Klüver2015). The estimate of parties’ positions on one policy issue (field) taken from the CHES database does not have to reflect the complex reality often associated with bills. CHES policy issues usually affect more policy fields, and even within one field, several issues may be covered by the varying positions of a given political party. Only a daunting detailed manual coding of key issues for each bill and the ascertainment of the positions of relevant actors (e.g. by experts) on bills may address the challenge (e.g. Thomson et al. Reference Thomson2006). The saliency of a bill to the coalition parties is similarly affected by the presence of multisectoral bills, but it is more valid within one policy field (either it is important or not for the party). The model shows that contrary to H2, if a bill is salient for other coalition parties not submitting the initial draft, it is changed less.

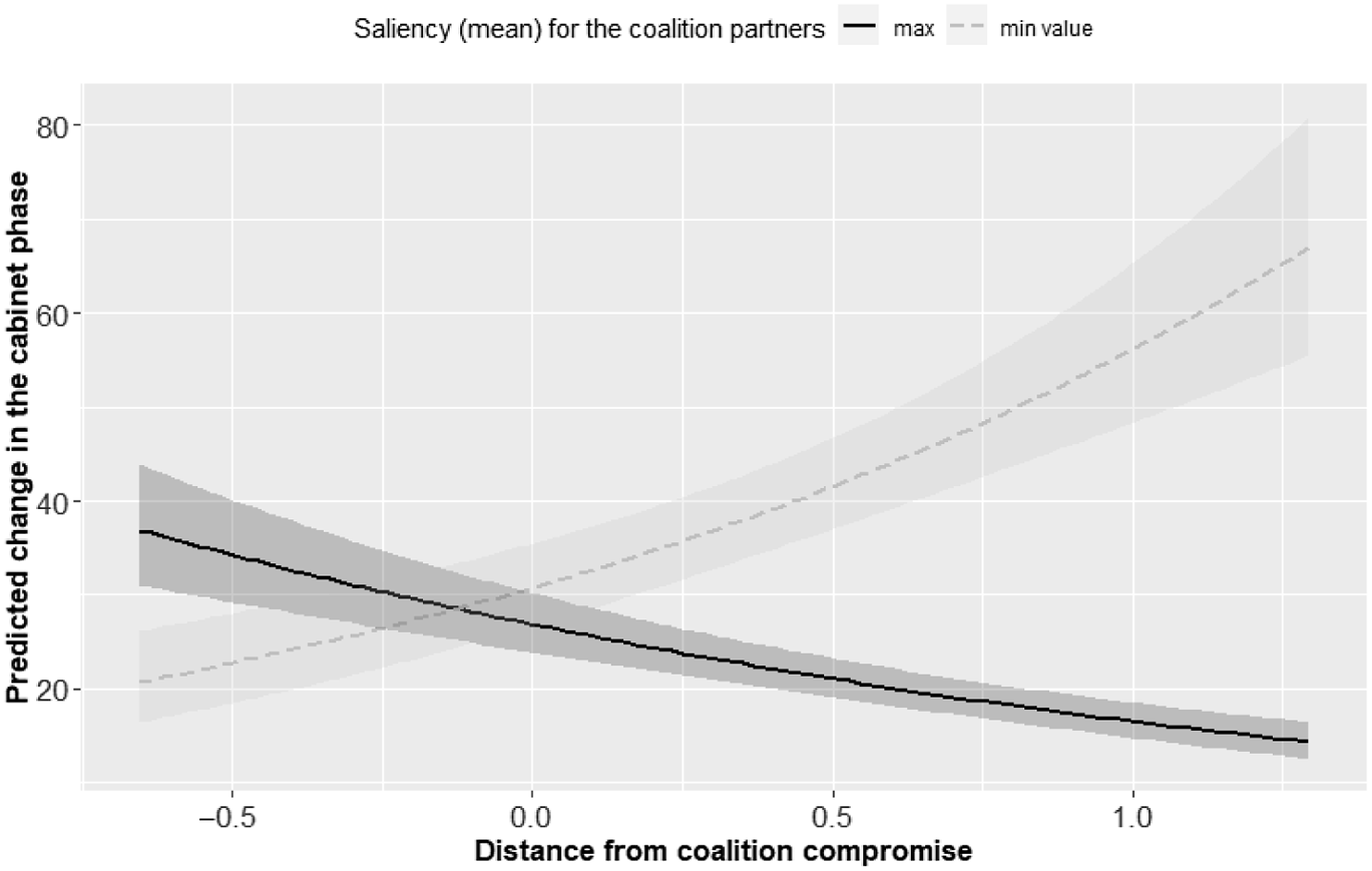

To explore the linkage between the saliency of a bill to coalition parties and the distance from the coalition compromise, we followed an approach by Höhmann and Sieberer (Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020) and also tested any possible interaction between the effects of both variables. Figure 3 (methodology based on Berry et al. Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012) tells us that a higher distance from coalition compromise brings significantly more alterations to less salient bills, while the correlation is opposite for more salient bills. The findings seem to indicate that a proposing ministry is willing and able to resist efforts to change bills that may be distinctive and important for the remaining coalition parties, while it does not mind accepting concessions to less crucial bills.

Figure 3. The effect of distance to coalition compromise conditioned by the saliency of a bill for coalition partners.

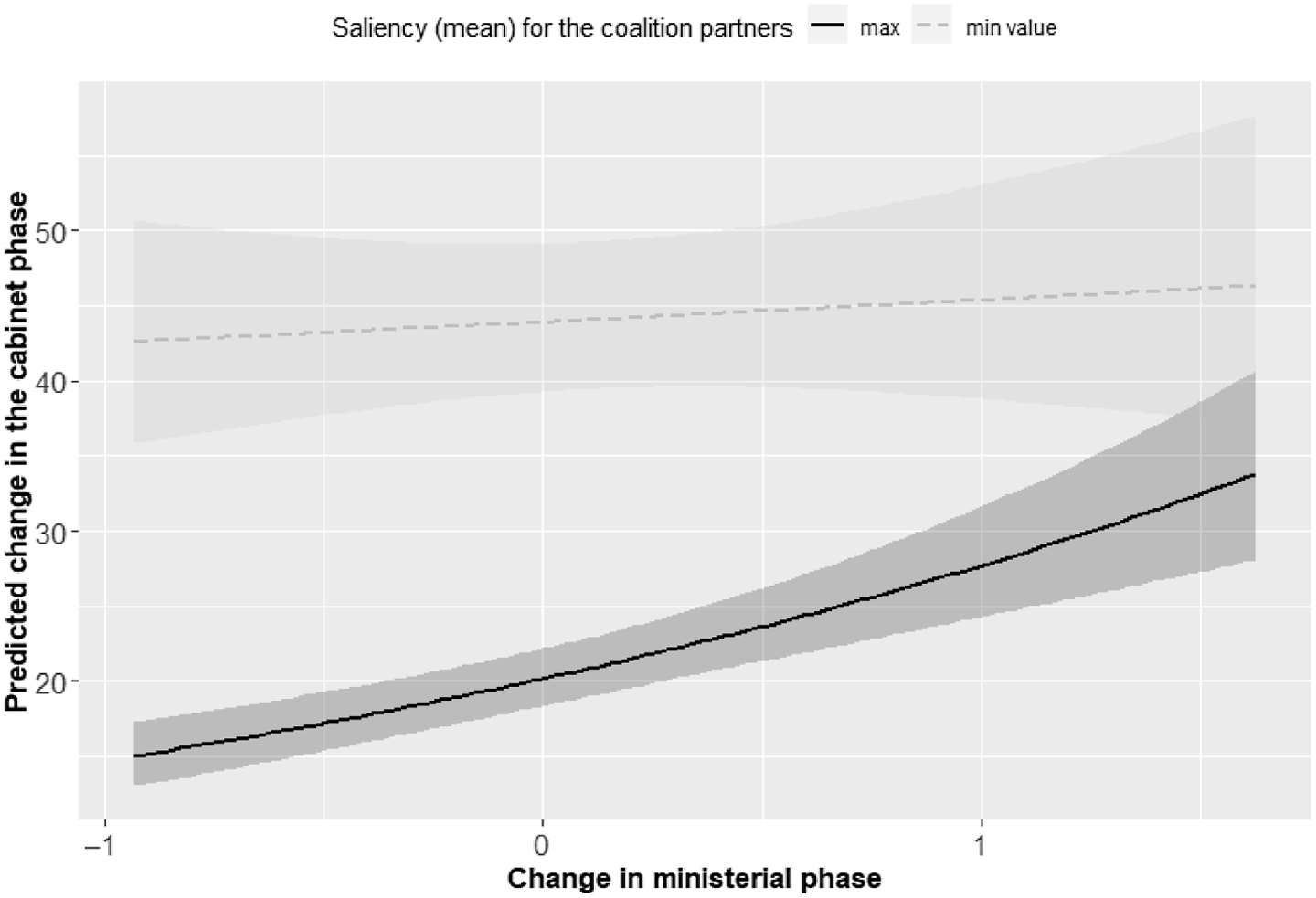

The hypotheses testing the application of an anticipated strategy by the ministries drafting the bill reveal rather mixed results. Inclusion of the bill in the GLP does not influence the incidence of alterations. Clearly at the point when the GLP is created most listed bills are too nascent in form to already contain a coalition consensus, confirming a piece of anecdotical evidence given by a Czech ministerial civil servant claiming that the placement of a bill in the GLP by the ministry does not bind it to the bill’s content (Vedral Reference Vedral, Gerloch and Kysela2007). It is more interesting that the role of the ministerial phase proves to be statistically significant and the effect is substantial, although in a different direction to that which we assumed. More changes to a bill at the preliminary stage by a ministry lead to more changes in the cabinet phase. If the ministries apply any anticipation strategy at all, it does not bear fruit later on. The finding scripts a different scenario in which the initial redrafting of a bill rather exposes the vulnerability of the submitting ministry, and other actors increase their demands, and that causes even more changes in the cabinet phase. Figure 4, providing an interaction with the saliency for the coalition parties, shows the “open the gates” effect is stronger for salient bills.

Figure 4. The effect of the ratio of the change to bills in the ministerial phase conditioned by the saliency of a bill for coalition partners.

The involvement of LGC manifests the strongest positive influence on the increase in the number of a bill’s alterations in the cabinet phase. The result is not wholly surprising because the LGC manages to scrutinise only a share of bills at its meetings (about 40 per cent from the sample) and logically selects bills that are, in a certain sense, “problematic,” i.e. their regulatory or legal quality is questionable or there are other controversies involved. Even if the body is formally independent of politicians, its members are selected by the government, and changes to bills discussed and offered by the LGC often have political repercussions. If the LGC recommendations overlap with the interests of any coalition party, it would be rational to let the LGC intervene and not use the party’s political capital in an attempt to directly persuade the initiating ministry. Unfortunately, the available data do not allow us to decipher the quantity of such overlap or to determine if it is coincidental or (covertly) caused by political pressure. We have tested for interaction between LGC participation and other variables, but no relationship appears statistically significant.

The results of the model indicate a statistically significant and quite strong effect of all control variables; in three out of four cases, the assumed direction was confirmed. The longer a bill lingers in the cabinet phase, a situation that most likely reflects the lack of consensus on the bill’s content, the more changes it undergoes. The negative impact of the length of the bill on its alterations is also logical. We recall that the DV is computed as a relative value of change. The length of bills varies from hundreds to tens of thousands of words, and it is unlikely that complex bills would be completely redrafted in the executive phase (it might be more effective to abandon a bill altogether), while the other subjects would preferably focus only on selected priorities. Finally, the model confirms that bills proposing new laws gain more attention and are subsequently changed more than amendments to existing laws. Only the impact of the timing of the submission of a bill does not follow the expected direction, and bills initiated closer to upcoming elections are altered more. Here we must admit that there are competing persuasive theories that are in line with our findings: for example that the coalition partners must first learn the mutual control mechanisms to use them effectively and that they defend their interests more aggressively with the approach of elections (Müller and Meyer Reference Müller and Meyer2010). The effect of electoral campaigning seems less pronounced in the executive than the parliamentary phase. Also, because the ministers know that bills need considerable additional time to receive the approval of the legislature, they almost always stop submitting any new bills to the government about one year before planned elections. Lastly, the result might be caused by the application of a simple strategy in which a minister prefers to start his/her period in office by initiating uncontroversial bills in order to score easy successes and leave more disputed proposals once he/she settles into his/her role.

Conclusion

The executive in parliamentary democracies plays an exclusive and prominent role in law-making. Previous studies primarily investigated the behaviour of coalition governments during the parliamentary phase and, at best, only touched on the preceding executive phase indirectly. This is not satisfactory because our unique data reveal that government bills in the Czech Republic are, on average, altered twice as much during the executive phase than in the parliamentary phase, indicating the importance of the drafting processes within the executive. Our article is the first attempt to close the knowledge gap and focuses exclusively on the impact of mutual control of coalition parties during the executive phase of law-making. The theoretical framework is tested on a completely new dataset with data from the Czech Republic.

Our findings indicate that coalition parties do keep tabs on one another during the executive stage of law-making, doubting the speculations of certain researchers that instruments available in that phase are insufficient to police any coalition bargaining (e.g. Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2014b). However, the results from the model show that theoretical assumptions from the parliamentary phase apply only partially. Policy positions on bills do not have any impact on the number of their changes, and bills salient for coalition partners seem to be more protected from alterations by the initiating ministry. Nevertheless, a more nuanced picture emerges if the two variables are interacted: less salient bills are changed more and vice versa. Second, the decision of a ministry to start accommodating demands for changes to a bill at the preliminary phase of drafting does not lead to the resolution of all existing controversies, but rather invites more alterations once the bill is submitted to the government. Third, the involvement of independent institutions scrutinising the legal and regulatory quality of bills significantly contributes to more changes to bills. The question is to what extent the recommendations of these bodies are technical (e.g. Schnose Reference Schnose2017) or political. If the latter is the case, then how do they link with the keeping tabs thesis. Finally, control variables performed strongly in the model; the most interesting show that bills initiated closer to coming elections suffer from more changes.

The article faces two caveats that call for further research. The single country case study design may bring into question the generality of the results. As noted above, the qualification of the Czech Republic as a prototypical case, and the similarity of the main features of the executive phase framework to many other states should ease any objections. Also, the operationalisation of the variables does not reflect any specifics of the Czech case and might be easily replicated in most parliamentary democracies. The collecting and testing of other sets of empirical data is thus desirable. Second, the political versus technical factors divide has more general repercussions for the inquiry into the executive stage of law-making. Several studies suggest that civil servants and not politicians are the real principals behind the drafting of bills (Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; Page Reference Page2012). The presented data at least partly allow us to contest that view, but the employed research design only addresses the issue indirectly. Qualitative methods such as in-depth process tracing would be needed to distinctify the nature of changes to bills and the identity of their initiators. Such an approach may also mitigate the difficulties that arise with the operationalisation of such variables as policy distance and saliency.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X21000258

Data availability statement

Here you can find the online appendix and supporting information. Lysek, Jakub, (2021). Replication Data for: In the Cradle of Laws: Resolving Coalition Controversies in the Executive Phase of Law-making,” https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LLRLQB, Harvard Dataverse.

Acknowledgement

The output has been financially supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GACR) as part of the grant project no. 17-03806S – Exploring the Dark Corner of the Legislative Process: Preparation of Bills by the Executive. We are grateful to the two Anonymous reviewers and Vladimir Matlach from the Department of General Linguistics of Palacky University in Olomouc that helped us with the text analysis.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.