Introduction

In 1972, Reginald Ford, well known in New Zealand architectural circles and a benefactor of the Auckland War Memorial Museum, died at the age of 92 years. Ford’s passing broke a link connecting the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), Antarctica, and New Zealand, for he was the last survivor of their National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery expedition) which overwintered on the continent 1901–1904 and on which Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Wilson, and Ernest Shackleton reached a new farthest south mark of 82.17’S. Various artefacts from the expedition, including a sledge harness, skis, telescope, knives and forks, an inkstand fashioned from a fragment of the Discovery’s broken rudder, and other items were gifted to the Auckland Museum on his death. His retention of these items suggests that at a personal level participation in the expedition remained a landmark event in Ford’s long life.

This paper first recovers, consolidates and extends the fragmentary details of Ford’s role in the “official” accounts of the expedition and then examines his later illustrated public lectures, particularly in New Zealand, where he settled in 1905, and where he continued to speak about Antarctica long after he had taken up a new career as an architect. Ford was neither an officer nor a scientist, which distinguishes his lectures and writing about Antarctica from the main published accounts of the expedition (Armitage, Reference Armitage1905; Bernacchi, Reference Bernacchi1938; Scott, Reference Scott1953; Wilson, Reference Wilson1966). These are discussed in the second part of the paper. Indeed, Ford as the expedition’s Steward could be considered an unlikely public lecturer.

The Royal Geographical Society’s Discovery Expedition 1901–1904 and Reginald Ford

The genesis of RGS interest in Antarctic exploration can be sheeted back to the furor over the non-admission of women as Fellows in 1893 (Bell & McEwan, Reference Bell and McEwan1996). The incoming president Sir Clement Markham sought to heal the breach by finding a new focal point for RGS activity – exploration of the still largely unknown continent of Antarctica. The International Geographical Congress held in London in 1895 provided a further platform for Markham to promote his ideas for a systematic scientific exploration of the continent (Markham, Reference Markham, Keltie and Mill1896). By 1901, the Discovery had been purpose built for the RGS and Captain Scott Royal Navy (RN) appointed to lead a scientific expedition of 50 officers, scientists and crew.

Ford was born in 1880, but many details of his early life are obscure and contradictory. Savours (Reference Savours2012) indicates he was the son of a gunner. He was born in London and baptised as Charles Reginald Ford; his father Matthew Ford is given as a butler. In the 1891 census, Matthew Ford is designated as a House Steward for a prominent surgeon, Dr Dyce Duckworth. Ford himself described his father as a private secretary to a Mr White, a Portland cement magnate, with whom he travelled with as far as the Mediterranean and India. The family of Quaker descent came from Staithes in Yorkshire where his father at one time worked on a Whitby collier. Ford attended the local education board Oxford Gardens Higher Grade School in London and like his older brother was intended for a career as an engineer with the Great Western Railway. Some weeks after leaving school, but before a vacancy occurred with the company, he chose instead at the age of 14 years to join the Royal Navy (RN). Ford’s father had died by this time and his mother passed away shortly afterwards. He later wrote that, the RN “opening was not what I had hoped for, but I took it anyway” (Ford to [daughter] Dorothy Stroh, 6 January 1967, MS 797 88/136 Folder 4). Over the next 5 years, he served in home waters and in the Mediterranean. He listed HMS Marlborough, a sail and steam powered former ship of the line (a training vessel in Ford’s time), Terrible (a Powerful class protected cruiser), Dido (probably the Eclipse second-class cruiser) and Caesar (a Majestic class pre-dreadnought) as vessels on which he served. Many details are lacking; however, he kept a diary, and his later newspaper articles suggest that in 1897 he served in the RN Mediterranean Squadron and was part of the International Squadron formed by the great powers of Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Russia and Great Britain to intervene in a rebellion of Greeks against Ottoman rule on Crete (Ford, Reference Ford1906a, Reference Ford1907a).

In 1901, Ford was on HMS Vernon, a shore-based torpedo school, at Portsmouth and listed as a Domestic second class when he volunteered for the Discovery crew. Himself a former torpedo officer, Scott’s approach to crew selection from a mass of applicants was to ask the opinion of his contemporaries now scattered across many ships in the fleet. Ford emerged successfully out of this process and was initially described as the “Ward room Stewart and assistant” and ranked 29 of the 50 strong crew (The National Antarctic Expedition, 1901). The Discovery departed on 6 August before this listing was published in The Geographical Journal of September 1901. By now, RN Warrant Officer Edward Else the first choice as Ship’s Steward had been replaced by Ford. In The Voyage of the “Discovery,” originally published in 1905, Scott recounted how Else had proved unsatisfactory as Steward and “eventually I decided to give it to C. R. Ford who, although a very young man without experience showed himself to be well fitted for it in other respects” (Scott, Reference Scott1953, p.55). Ford was 21 and Scott 32.

The Discovery arrived at its penultimate base the port of Lyttleton, New Zealand, on 29 November 1901, to collect 22 sledge dogs sent separately by a faster vessel, to re-provision with various local farmers donating sheep, and before heading south calibrate the magnetic equipment. The arrival of the Discovery was an occasion for considerable patriotic celebration. There was a large “citizens banquet” hosted by the Philosophical Institute of Canterbury, attended by the officers, scientists, selected crew and over 100 local notables. Scott spoke briefly about their purpose remarking that, “Primarily, however, the expedition was a geographical one. Its mission was, first, to discover the nature and extent of the South Polar lands” (The Discovery, 1901). The Discovery had hundreds of visitors before 21 December when it left Lyttelton for Antarctica, although there was an unscheduled landfall at Port Chalmers to return to shore the body of a crew member who died after falling from the mast.

Scott (Reference Scott1953, p.55) later acknowledged the importance of Ford’s work as Steward explaining what he meant by “well suited” to the role; “He soon mastered every detail of our stores and kept the books with such accuracy that I could rely implicitly on his statements. This also was no small relief where it was impossible to hold a survey of the stores which remained on board.” This is confirmed by scrutinising the list of stores calculated at 2 1/2lb of food including 1lb of meat per man per day published while in Lyttelton (The Discovery’s Stores, 1901). Scott rightly praised Ford’s precision and accuracy. Ford next appears in Scott’s narrative when, on 17 February 1902, he fractured his leg in a skiing accident which laid him up for 6 weeks (Scott, Reference Scott1953, 164). On other occasions, Ford is mentioned generically, regards off-ship time for cooks and stewards (Scott, Reference Scott1953, p.219) and as one of the four men remaining on the Discovery on the return of Scott’s sledging party in December 1903, with the rest of the crew being employed on ice sawing duties (Scott, Reference Scott1904, p.23; Reference Scott1953, p.628–629).

Expedition doctor Edward Wilson also kept a diary, though this was intended as a family record and not for publication, which was delayed until 1966. Ford is mentioned periodically in Wilson’s account. The first occasion being the splinting of his leg after the skiing accident referred to by Scott, culminating in an entry for 12 April 1902 noting that the fracture was “sound” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.132). Their respective roles intersected, when Ford would awaken Wilson at 7.30 a.m. to taste the cans of condensed milk “to find seven that haven’t gone bad” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.151). There is a hint of naval hierarchies in Wilson’s description of Ford waking him with, “Doctor Wilson, Sir, milk inspection Sir” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.151) and more so on the solstice when to an equivalent of a British Christmas meal, “the four Warrant officers had been invited, namely the Bo’sun, the Second Engineer, the Chief Carpenter and the Steward. They were all great fun and enjoyed themselves well” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.266). This dinner invitation was repeated when the sun reappeared on 23 August 1903 (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.285). Finally, on the return voyage to New Zealand, Wilson noted that Ford was among a party of 11, including Scott and himself, that rowed to Enderby Island (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966, p.349). Wilson’s account also clarifies Ford’s status during the expedition; Scott’s original Steward was a RN Warrant Officer, in line with the responsibilities of the position, Ford did not hold this rank in the RN, but having assumed the duties of Steward for the duration of the expedition was accorded the status of Warrant Officer. This helps explain the various ranks accorded to Ford in later accounts of the expedition.

A third published account of the Discovery expedition was authored by Albert Armitage, the second in command. A P&O officer with previous arctic experience and a RN background, which led to Markham seeking his services, Armitage (Reference Armitage1905, vii), described his account as a “simple tale devoid of scientific theories and speculations, which chiefly deals with the lives during three years of half a hundred men.” Ford’s broken leg marks his first appearance in Armitage’s account, though with the added detail that he had been warned of the dangers if his feet “would not slip off the ski when he fell” (Armitage, Reference Armitage1905, p.63). Ford’s competency in his role as Steward was fleshed out beyond Scott’s description. “Mr Ford, not only had to keep an account of all the stores and see to their issue,” notionally under the control of Lieutenant Shackleton and later Lieutenant Michael Barne but “also acted as secretary to Captain Scott, and weighed and bagged all the provisions that were taken on the various sledge journey” (Armitage, Reference Armitage1905, p.102). This latter task was an important responsibility upon which lives depended. Armitage (Reference Armitage1905, p.103) also praised him for the selection of meals which “managed to satisfy us all, and even astonished us by the variety of the bill of fare that he provided on festive occasions.” When some of the party developed signs of scurvy, Ford was directed to provide fresh seal meat and lime juice for all hands (Armitage, Reference Armitage1905, p.138). In addition, Armitage (Reference Armitage1905, p.102) noted that, Ford “was a good photographer.” Louis Bernacchi, the expedition’s physicist, barely mentions Ford at all.

By his own account, Ford (Reference Ford1908a, p.8–9) had gone ashore at Cape Adare at the beginning of the expedition in January 1902, where he had been intrigued by the behaviour of Adélie penguins. He was also part of a sledging party with Fred Dailey RN [carpenter] and Thomas Whitfield RN [stoker] from 1 to 17 January 1903 that laid a depot for the southern party at Minna Bluff some 56 miles [90 km] from the Discovery in anticipation of the return of Lieutenant Armitage and party. They were also to collect any items that Barne had been unable to carry on his trip to the depot a week earlier. Ford kept a record of the trip and later typed a final version of the journey, illustrated with fine ink drawings and water colours. He covered the practicalities of sledging, skiing, tents, food and equipment, while describing the surface appearance of the snow in some detail (Ford, Reference Ford1903). Ford’s sledging trip escaped attention in Scott’s account. Much later he observed privately that, “it was of equal importance and length of others that were recorded in Scott’s narrative… at the time I was a bit disappointed at the omission” (Ford to Quartermain, 6 April 1964, MS797 Folder 2). He offered as an explanation that Lieutenant Charles Royds had authorised the journey in Scott and Armitage’s absence and Ford reported to him on his return, but that Royds may or may not have informed Scott. After half a century, he was also prepared to see fault in RN procedure: “there was not a commissioned officer in charge therefore it was not worth recording” (Ford to Quartermain, 6 April 1964 MS 797 Folder 2).

Ford also contributed to one of the more memorable morale boosting efforts of the expedition: the “South Polar Times” produced during the winter months. This was initially edited by Shackleton and appeared monthly, the single copy being passed around amongst the crew (Fadiman, Reference Fadiman2012). Ford produced additional artwork including three full page water colours and typed much of the 1903 issue after Shackleton was invalided home (Savours, Reference Savours2012). He also authored, under a pseudonym, a lengthy article about earlier ships bearing the name Discovery (Historicus, 1903; Savours, Reference Savours2012).

After the Discovery returned to the UK in September 1904, Ford acted as Scott’s secretary and accountant in the winding up of the affairs of the expedition (Savours, Reference Savours2012). In December 1904, Scott gave an illustrated address using 150 slides before an RGS meeting chaired by Markham and held on this occasion in the Albert Hall. At the conclusion of the 90-min address, Scott was presented with a specially struck RGS Antarctic Medal in gold. The officers and crew received it in silver. The Discovery crew were all awarded a Polar Medal. Ford’s medal would ultimately be displayed in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Thereafter, Scott gave lectures and took leave from the RN to write The Voyage of the “Discovery,” his account of the expedition.

Ford did not rejoin the RN but delivered his own lectures in England and afterwards in Canada, the USA, Australia and finally New Zealand. In the UK under the title of “Ice bound in the Antarctic” he spoke at the public hall in Slough on 22 February 1905, the event being organised by the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society (Slough Observer 25 February 1905, copies in MS 797 Folder 1). Based around 150 lantern slides, “the lecture was by no means of a dry scientific character” (“Lecture by Mr C R Ford” The Whitby Times 3 March 1905 copies in MS 797 Folder 1). Over the course of an hour, Ford showed slides of icebergs, blizzards, seals, birds, and spoke about the daily routine, clothing, and freeing the ship from the ice. The Whitby Gazette 3 March 1905, reporting on the same lecture, the literary and philosophical society hosts notwithstanding, referred to the “mannerless conduct” of one member of the audience who in a “grating stage whisper” provided an alternative commentary on the slides (Whitby Gazette 3 March 1905 copies in MS 797 Folder 1). Civic culture sometimes needed to be built from a low base. Ford repeated the lecture at Sandsend.

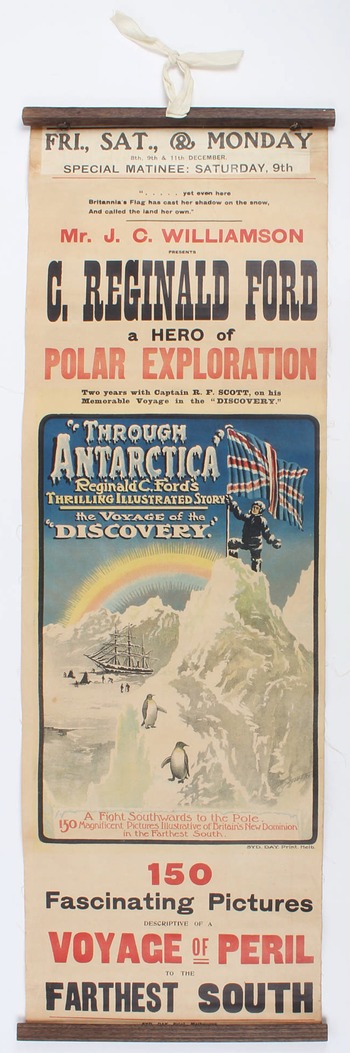

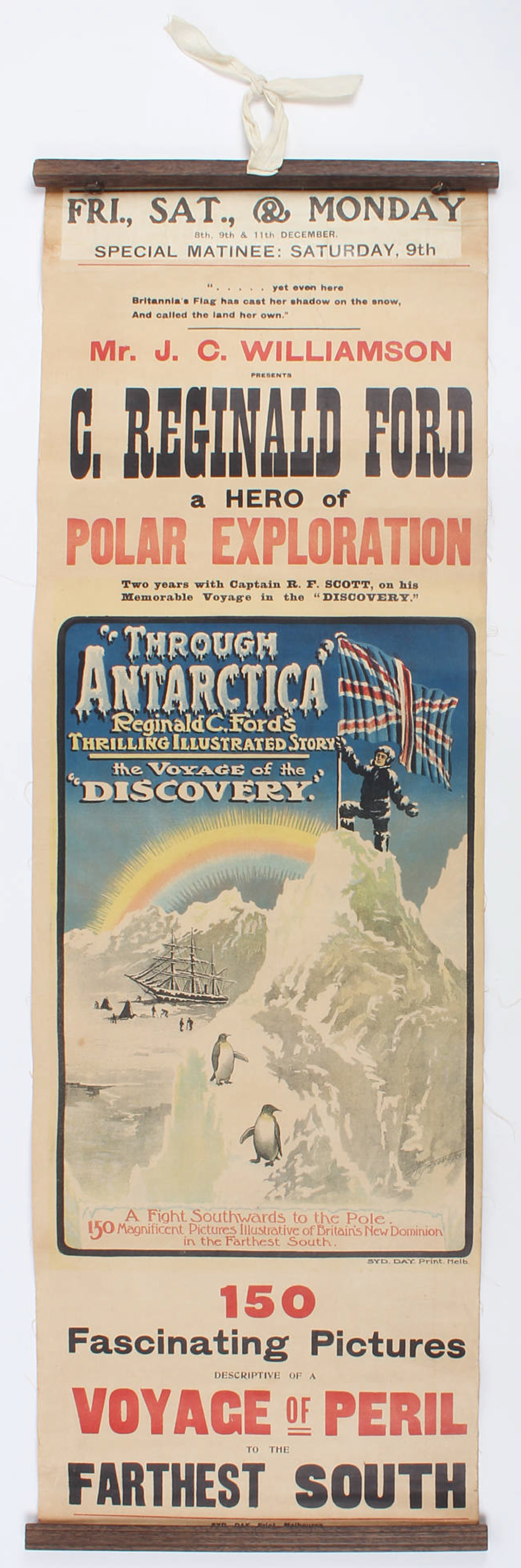

Shortly afterwards Ford left for Canada, making use of contacts provided by Markham intending to migrate and gave further lectures, but after 7 months spent in Ottawa, decided his prospects were limited. He then travelled to Australia where a lecture tour was organised by J. C. Williamson, an Australian-based theatre owner and promotor mainly of touring theatre and musical companies. Ford was not the typical J. C. Williamson performer, but he must, nevertheless, have been considered a commercial proposition: the unknown and extreme environment, challenges, heroism and imperial triumphs meant “Ice bound in the Antarctic” was reshaped into something more dramatic entitled “Furthest South.” Ford spoke in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart as well as some smaller centres from August to November 1905. There were repeat lectures in the large cities. Typically, he was interviewed by newspaper reporters to generate publicity for the lecture. The Brisbane Courier described him as “one of the officers of the good ship Discovery,” not a claim that Ford ever made himself, but one that was repeated on the Australian and New Zealand legs of the tour (Mr C. Reginald Ford’s Lecture, 1905, p.3). The imagery of the accompanying poster was decidedly heroic and imperial; a fur clad figure standing atop the ice holding a large Union Jack, there are penguins, an ice-trapped vessel and wording that grandly, and inaccurately proclaims, “a Fight southwards to the Pole 150 magnificent pictures illustrate Britain’s new Dominion in the farthest south.” This poster was of J. C. Williamson and not Ford’s making (Figure 1) and exemplified what Pat Millar termed the “cultural imaginary” of Antarctic exploration. The Charles Ford of Scott’s Voyage of the Discovery, as a “reconstruction of self,” becomes C. Reginald Ford in Australia. “Furthest South” became a polished lecture based around 150 lantern slides, delivered in a fluent but engaging style free of oratorical flourishes. Other J. C. Williamson promotional material included a “synopsis of the narrative” which provides some clues as to Ford’s presentation. After outlining its objectives, the synopsis in chronological fashion traced the journey of the expedition with particular attention to the natural environment (Ford papers, MS797 Folder 1).

Figure 1. Farthest South Lecture Advertising Poster 1905. Poster: Through Antarctica Reginald Ford’s Thrilling Illustrated Story – The Voyage of the “Discovery.” 2014.x.135. © Auckland Museum CC BY WC Williamson poster.

The public lecture and photography

The public lecture in the first decade of the 20th century, if not enjoying the prestige it had previously, was still a popular and important event. Innis Keighren (Reference Keighren2008, 93), for instance, observed that, “as a venue for the dissemination of knowledge, the popular lecture was often implicated, through the activities of local scientific and literary societies, in the process of defining civic culture.” Subsequently, he suggested that “What distinguishes the spoken word from the written is, perhaps, the standards by which trustworthiness is claimed and assessed” (Keighren, Reference Keighren2008, p.177). Alongside the scientific lecture, the travel lecture was also a popular form of delivery (Scott, Reference Scott1980, Shepard, Reference Shepard1987). But it was more than just the spoken word at play, for use of lantern slides now added a further dimension to the public lecture. As Robert Nelson (Reference Nelson2000, p.415) remarks, “In the slide lecture, the image, that shadow or representation on the wall, never remains mere projection, mere being, because it is part of a performative triangle consisting of speaker, audience, and image” and furthermore that, “Because of the general acceptance of the photograph’s ability to represent faithfully and accurately, the tenor of slide shows shifted from illusion to realism, from phantasmagoria to science” (Nelson, Reference Nelson2000, p.428).

Photography went hand in hand with the heroic age of Antarctic exploration. Not only did it assist with fundraising, but Millar, (Reference Millar2012, p.412) suggests that, on a “deeper level, photography played an important role in structuring understandings of Antarctica and enabling images of it to begin to operate within cultural memory.” Antarctic photography was difficult with unwieldy tripod mounted cameras, glass plates and long exposure times, although those on sledging parties and Ford himself possessed easy to use handheld cameras. Frank Hurley (on Shackleton’s Trans Antarctic Expedition and both of Mawson’s expeditions) and Herbert Ponting (Scott’s Terra Nova expedition) were pioneers of Antarctic photography (Mundy, Reference Mundy2014). The “cultural imaginary” of early 20th century Antarctic exploration in photography “involved images of ice, ships in the ice, and generally associated discourses of masculinity, adventure, and nationalism” (Millar, Reference Millar2018, p.51).

In addition to the images of Hurley and Ponting, the photographs and slides of “second tier” expedition members have attracted attention. For instance, the hand-coloured lantern slides made from images taken by Australian Keith Jack, a member of Shackleton’s Ross Sea party (1914–1917), “have much in common with others of the Heroic Era, showing icescapes, ships, isolation and ways in which the expeditioners placed themselves within this landscape” (Millar, Reference Millar2012, p.441). There is, however, no record of Jack’s slides being used in public lectures.

Ernest Joyce, a member of the Discovery expedition, Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition, and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Ross Sea Party, is another whose slide collection has been carefully studied. Many but not all are Joyce’s own photos. McCarthy, Bowring, & Storey (Reference McCarthy, Bowring and Storey2011, p.165) note the “emphasis on lantern slides also marks this out as a group of photographs intended to be shared with others, in public situations, where they provide ballast for Joyce’s ongoing reconstruction of self.” On his death certificate, he was listed as “Antarctic explorer.” Many of the images examined by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Bowring and Storey2011) show people, dogs and equipment. Jack, in contrast, has more slides of the natural environment. The exact number of lectures Joyce gave is unknown. Like Ford, Joyce had entered the RN as a boy and was recruited to the Discovery by Scott on the South African stopover, but, unlike Ford, never overcame the boundaries of his naval training, in his respect for authority and limited initiative (Jones, Reference Jones1984). Joyce never received the credit he felt his due.

Ford took his own photographs on the Discovery expedition, a personal rather than official record of the expedition.

Reginald Ford in New Zealand

In December 1905, Ford disembarked in Wellington to continue his J. C. Williamson lecture tour. His arrival had been foreshadowed in New Zealand newspapers 2 months earlier but ultimately commenced on Friday 8 December 1905 when his lecture was introduced and chaired by none less than the Premier “Dick” Seddon, in evening dress. The Evening Post captured Ford’s style of delivery and the audience response. Making use of lantern slides he,

gave no formal oration, but carried the audience on briefly from point to point as the successive landscapes and views were presented in rapid and orderly sequence. He had the vast advantage of having been an actual observer of the scenes and participator in the events, and his descriptions were singularly vivid and lifelike, and, abounded in quaint humour. Never before had the audience such a presentment of the solitude, the grandeur, the mystery and the terror of the far southern seas. Few human eyes have seen the icy coasts and live volcanoes and mountain peaks of which the forms were exhibited last night, and it was brought home to the audience that there were vast untrodden wastes and unnavigated waters on our planet of which we know little more than we do of the reverse side of the moon (Antarctic Exploration, 1905, p.5).

The newspaper reporter here provides clues to the dynamic linking Ford, his audience and the images. The attendees directly responded to his lantern slides with Ford figuratively, and probably literally, standing to one side and offering comment that took them from one image to the next. Promotional efforts had stressed that Ford’s lecture would be “anything but dry,” which by implication was the nature of a scientific address and would also “be illustrated with beautiful lantern views of scenes in the Antarctic region” (Chat with an Explorer, 18 October 1905, p.68). Appreciative as Ford’s audience was, the hall was however, not full too capacity (Life in the city, 1905, p.3).

Ford’s photographs and slides

Ford’s Antarctic lectures were anchored on a set of “150 lantern slides.” Ford’s numbered glass slides survive in the Auckland War Memorial Museum collection. Not all of the slides were Ford’s, included are some classic images of sledge parties in a blizzard reproduced from photographs taken by others on the expedition. There are also sets of photos attributed to him held at the Scott Polar Institute at Cambridge University and at the Australian Maritime Museum in Sydney. Most of the Auckland slides are marked “C R Ford” and potentially are more likely to be his own images. Since the focus here is on the delivery of Ford’s illustrated public lectures, whether they are Ford’s own photographs, as the majority seem to be, or include other images taken during the expedition is not a major stumbling block. These are the images that Ford spoke to – 150 or so for the full-blown version, but some renumbering on the slides suggests that they were reassembled for specific shorter talks. The advertisements for Ford’s “Furthest South” promised it would not be “a dry, scientific story of exploration – but tells a story of struggle and adventure with the great and unknown forces of nature in the Antarctic regions” (Two years in the Ice, 1905, p.5). Ford furthermore was described as “a clever, bright, and racy narrator, with remarkable descriptive powers and a gift of humour” (Two years in the Ice, New Zealand Times, 1905, p.5).

The choice of images and their sequencing provides clues as to the structure of Ford’s lecture, and by referring to newspaper accounts and some of his associated writing, it is possible to reconstruct how he described the Antarctic environment. The numbered slides, in general terms, take the form of a chronology of the expedition – in line with the synopsis that J. C. Williamson created for the Australian lectures. It begins with various early maps showing a presumed Antarctic continent, then moves with portraits to mention James Cook and James Ross, before featuring shots of the Discovery under construction, the crew, pack ice and the scenes around the wintering over base, icebergs, Cape Adare, Discovery icebound, sledging parties, the crew playing games on the ice, crevasses, dog teams, men pulling sledges, men in tents (and sketches of how they fitted in these), penguins and seals, Discovery and relief vessels, and concludes with some maps of the new features discovered in Antarctica. This sequencing is corroborated by a detailed newspaper report of his first lecture in Wellington.

In imagination the hearers were carried from Lyttelton further and further south until pack ice appeared, and by degrees the ocean became a white sheet to the horizon on every side. Then came the iceberg region, and the lecturer said that the thousand-feet-high [300m] bergs of ordinary literature, extending anywhere up to sixty miles [100km] in length, had no real existence. Two hundred feet [60m] was about the limit of height, and six miles [10 km] was a very exceptional length – nevertheless, these vast masses of ice, of which three-fourths lay below the waterline, were impressive enough. One of the most magnificent pictures of the series showed an old berg, honeycombed with vast and gloomy caverns, into which the long dark swell of the ocean washed, as the lecturer explained, with weird and hollow thunderings. Then came the coast of Victoria Land, the two great Antarctic volcanoes, the celebrated vertical ice-wall, 200 ft [60 m] high, extending in an unbroken line for four hundred miles, then about four hundred miles [640 km] more of exploration of coast which no previous navigator had seen; then the choice of winter quarters for the camp, the strange and abundant fauna of the inhospitable land, the daring sledge-expeditions, so fruitful in scientific knowledge; the hardships of the parties caught in an Antarctic blizzard (Antarctic Exploration, 1905, p.5)

Ford was following quite closely the “cultural imaginary” of Antarctic exploration. What is not obvious from the newspaper summation is that Ford’s lecture, visually at least, covered some topics more fully than others. Over 50% of the slides were comprised of maps of the continent (reproduced from an article in The Geographical Journal) and sledge journeys (17%), penguins and seals (18%), icebergs (9%), Mt Terror and Mt Erebus and surrounding landscapes including crevasses, and loading and departure of sledge parties (7%). The remainder of the images move from the construction of the Discovery, the ship encrusted with ice and crew at work, the furthest south party, and an iconic image of men in a blizzard. A newspaper reporter wrote approvingly that, “some of the views shown indicated that the lecturer could only have obtained them in positions of great personal discomfort and peril, he said nothing about himself at all” (Through Antarctica, 1906, p.7).

Ford still walked with a limp for 12 months after his leg had healed and was not considered fit for any extended journey (Ford to Quartermain, 6 April 1964, MS 797 Folder 4). Although he eventually managed to participate in one sledge journey, his responsibilities meant that many of his images capture adjacent to shipboard scenes including the loading of sledges as well as penguin and seal colonies. Ford was also much interested in the pack ice and icebergs. He wrote separately about these after returning to New Zealand.

The 2-h lecture in Wellington was repeated four times. Ford then travelled to Christchurch. Postponed from late December to early January 1906, he next gave his “Farthest South” lecture at the Oddfellows Hall in the Mid-Canterbury town of Ashburton. The venue was “very sparsely filled” and the newspaper report noted that “Mr Ford deplored the smallness of the audience” (Furthest South, 1905, p.3). The implication is that the tour was now failing financially, though this point of view is tempered by noting that the advertisements for the Ashburton lecture indicated that “Proceeds less Expenses in aid of Dr Barnado’s Homes and the [local] Hakatere Club” (Furthest South, 1905, p.3). On 11 January, however, George Tallis from J. C. Williamson wrote, “sorry that the New Zealand experiment did not turn out more satisfactorily,” adding that public interest in Antarctica had waned: “you have missed the boat for a boom by quite 12 months” (Tallis to Ford, 11 January 1906 MS 797 Folder 2). In mid-January, Ford announced that his lecture tour had finished and that he was joining Christchurch auctioneering and real estate firm Baker Brothers (Properties for sale, 1906). Before the year was ended, he had moved on to set up in partnership with A.K. Hadfield as Ford and Hadfield, auctioneers, share brokers, and real estate agents – Ford was described as “already well-known in Christchurch” (Personal, 1906, p.7; Properties for Sale, 1906, p.12). The Christchurch evening paper, in a display of civic pride, announced that Ford, a new resident of the city, along with other members of the expedition had been made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS) at the RGS’s 17 December 1906 meeting in London (Personal, 1907, p.3).

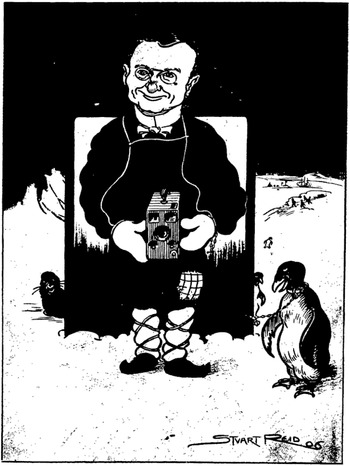

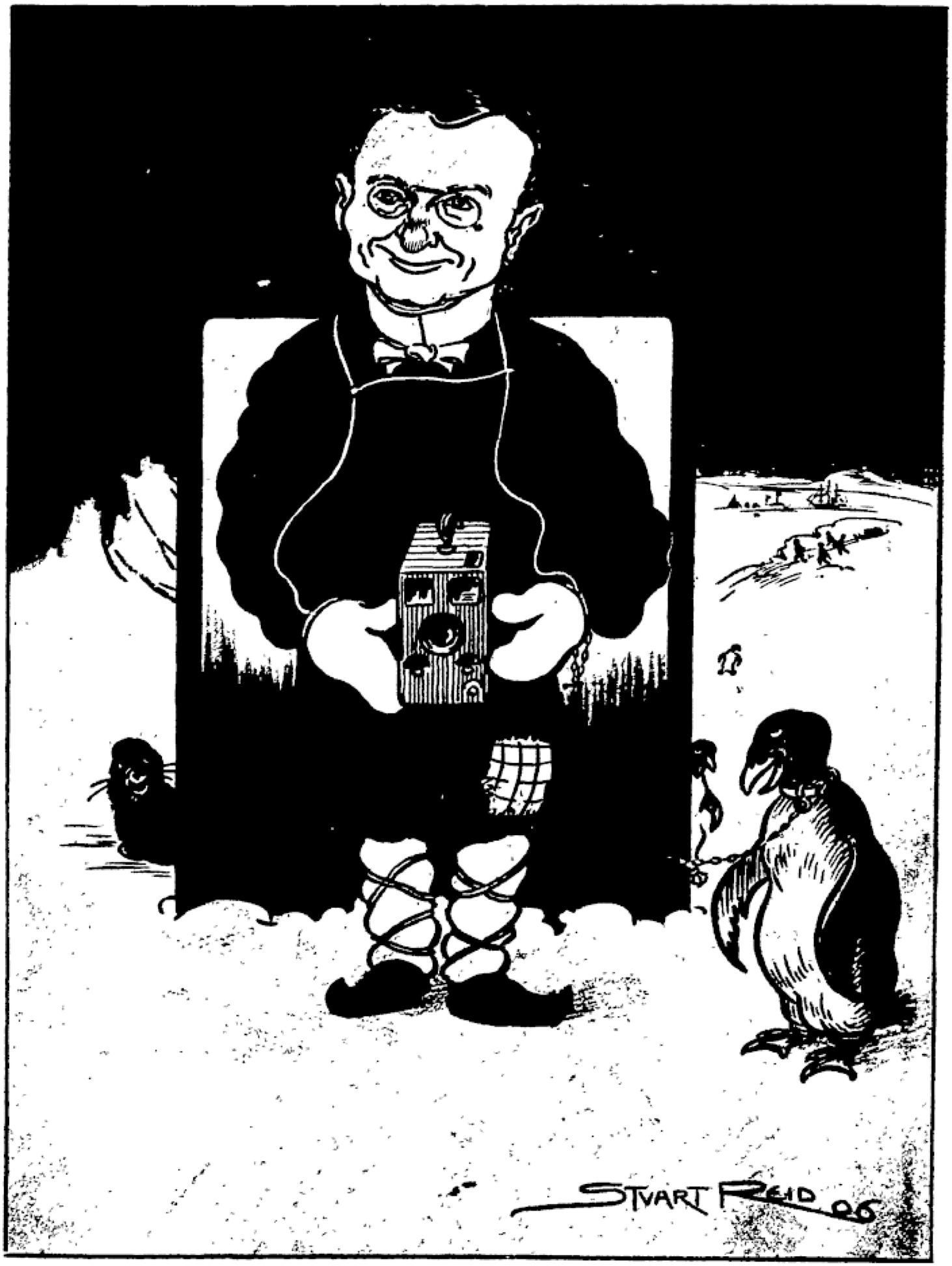

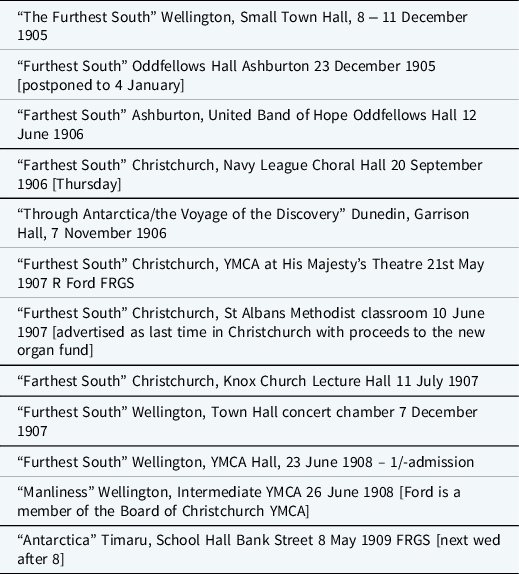

Once established in the city, Ford, now free of J. C. Williamson connections, on occasions repeated his “Furthest South” lecture. This started with a happier experience in Ashburton on 12 June 1906 and other presentations followed in Christchurch, Timaru, Dunedin and Wellington. The Dunedin and Wellington lectures were full-blown affairs at the Garrison Hall and Town Hall concert chamber, respectively, where remuneration was likely a significant consideration. The Otago Witness reported that, “They saw many photographs taken by him reproduced, however, which did credit to his enterprise” (Through Antarctica, 1906a, p.65). He even featured as an Antarctic photographer in a series of newspaper Otago Witness caricatures (Figure 2). The motivations for some other lectures may have been different, as former RN, Ford probably spoke to the Navy league out of a sense of duty. Ford’s comments about penguins in this lecture were reported on in some detail: the “animal world exhibits some strange vagaries ….The smaller of the common penguins of the south, he said, chose the warmest months for breeding in. But the Emperor penguin’s breeding habits were so wrapped in mystery till the late expedition that no one ever knew if it laid eggs” (Town and Country, 1906, p.6). The significance of this natural history focus will be returned to shortly. He was a board member of the YMCA in Christchurch explaining YMCA-related lectures, and others were more altruistically linked to fund raising, for example, for a new church organ (Table 1). The advertising for some of these lectures further credentialed Ford as FRGS. But was the “last time in Christchurch” tag on advertising for the 10 June 1907 lecture intended to boost attendance or a sign of lecture fatigue on Ford’s part?

Figure 2. Witness portraits No 7 “Look pleasant please,” Mr Reginald Ford snapshotting in Antarctica. Otago Witness, 14 November 1906, p.43.

Table 1. Repeats and variations of the “Furthest South” Lecture 1905 to 1909.

Sources: Compiled from Paperspast.

The exact nature of “Furthest South” probably altered slightly each time Ford gave the address, and it was not scripted and there would have been different points of engagement with different audiences. Ford was becoming adept at reading his audience – in the Choral Hall he was reported as stating, he was not giving a lecture, “and he emphatically proved it. It was a most interesting and vivid description – made all the more intense and realistic by the fact that the narrator took part in the events” (Farthest South, 1906, p.9). On another occasion, it was reported that “the lecture itself, though ‘popular’ in form and matter, bordered at times on the deeply scientific, and touched such interesting things as magnetic observation, a subject which some of the audience at least would have liked to have heard more about” (Through Antarctica, 1906, p.7). Shackleton’s second Antarctic expedition 1907–1909 may have increased local interest, but Ford appears to have shelved his original “Furthest South” lecture in 1909. He had begun to study architecture in 1906 and married in late 1908 (Lowe, Reference Lowe1998).

In 1907, Ford drew on his Discovery diary to write an article for the Lyttelton Times about the landing on South Trinidad Island in the South Atlantic on the outward voyage in 1901 (Ford, Reference Ford1907). He also published at least two articles on the Discovery voyage in a shipping company house journal and an Australian monthly magazine (Ford, Reference Ford1906; Reference Ford1908). The latter included illustrations based on Ford’s sketches of the Discovery and of icebergs. For these articles and others in Australian and New Zealand newspapers (Ford, Reference Ford1907), he presumably received a fee, which may have helpfully augmented his income. In one article, he endeavoured to answer the question of wherein lay the fascination of Antarctic exploration, settling not on the science but on “the beauties of the pack ice and icebergs, the grandeur of the ice-covered lands, the glories of the sun rises and sunsets, and of the auroral displays, the mystic silence of the Antarctic night” (Ford, Reference Ford1906, p.223–224). The other article focused on icebergs and although Ford quoted details of their size and displacement, his response was more aesthetically weighted. This piece also included illustrations reproduced from Ford’s own sketches.

These tabular bergs are the ones most commonly met in the Antarctic. They have a majestic appearance. When seen full in the light of the sun they are of dazzling whiteness. When in the shadow on a stormy day they are a dull and deathly grey … but seen in the light of the rising sun or setting sun they are transformed. They reflect every hue of the sky, and are in turns every shade of purple, crimson, and orange, and when the sun is just peeping over the horizon they look like masses of molten gold (Ford, Reference Ford1908, p.488).

Ford penned evocative descriptions of the Antarctic environment. It is not unreasonable to believe that many of these phrasings may have been polished in his public lectures. In 1908, local publisher Whitcombe & Tombs brought out a 5000-word illustrated booklet based on extracts from his Discovery diary (Ford, Reference Ford1908a). The fate of his full diary written in pencil in penny notebooks is unclear.

By 1907, Ford was secretary of the boosterish Advancement of Canterbury Association, run by his future father-in-law (Advancement of Canterbury, 1907, p.4). In 1909, Scott asked Ford if he would join his second expedition or failing that to act as his agent in New Zealand. Ford demurred suggesting Christchurch merchant and philanthropist Joseph Kinsey was better placed to serve in this capacity (Antarctica, 1909, p.5). When word of his old commander’s death reached New Zealand, Ford penned some paragraphs for local newspapers. These included recollections of Scott at Burlington House in the early stages of the expedition, “amidst apparent wild disorder, noting his genius for organisation and command, and his gift of drawing out the best in his subordinates” (The Explorers, 1913, p.10). He recalled other instances of Scott in command when the Discovery was in danger from icebergs as well as offering more informal memories of Scott making toast, while Ford prepared the men’s porridge. This was very much a RN crew inflected picture of the officer Scott, resolute, calm and determined when under pressure.

In 1913, Ford left Christchurch for Whanganui to begin his new career as an architect (Personal, 1913, p.4). In 1923, he relocated to Auckland and in 1924 the partnership of [William] Gummer and Ford was established and lasted until their joint retirements in 1961. Ford was prominent in the New Zealand Institute of Architects and in the management of the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Once in Auckland, Ford recommenced offering lectures about Antarctica. That his own direct experience was now two decades old, he finessed by repackaging his knowledge in an historical context as the “Romance of Polar Exploration” and also by emphasising natural history (Table 2).

Table 2. Ford’s “Romance of Antarctica” Public Lecture 1924 − 1926.

Sources: Complied from Paperspast.

The “Romance of Polar Exploration” was delivered in suburban Auckland as part of the Epsom Library winter course of lectures from 1924 to 1926 and at the Grey Lynn Library in the latter year. Ford’s authority was now his FGRS as much as his being on the Discovery expedition, particularly in the wake of Scott’s second and Shackleton’s two expeditions. In these presentations, Ford ranged widely across Arctic and Antarctic exploration. His own copies of The Geographical Journal received by virtue of being a FRGS gave him access to reports on Arctic and Antarctic exploration since the Discovery expedition. He discussed Scott’s ill-fated expedition in detail. Now Ford offered a muted criticism, “giving it as his opinion that had Scott but resorted to dogs as a means of hauling his sledges he would have got through” and perhaps by implication beaten Amundsen to the pole (Polar Exploration, 1925, p.11).

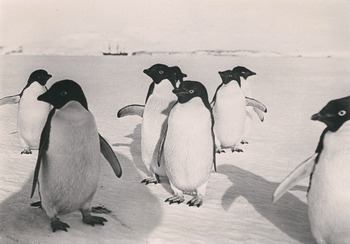

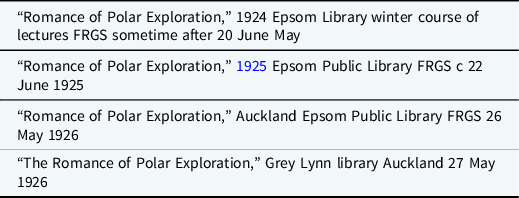

Ford had always taken an interest in natural history, particularly the birdlife and seals he had encountered on the voyage. He was a careful observer and could paint a vivid word picture. He also had his slides (Figures 3 and 4). His natural history recollections did not date in the same way as the human aspects of the Discovery voyage. As late as 1930, he was part of an Auckland Zoological Society series of radio broadcasts and spoke on the topic of “Birds and Seals of Antarctica” (Lectures for 1YA, 1930, p.18).

Figure 3. Penguins on Ross iceshelf with Discovery in the background. PH-CNEG-C15085, PH-1970-8-C15191. (Auckland Museum collection).

Figure 4. Seal in hole in Ice PH-1970-8-C15198, PH-CNEG-C15085 (Auckland Museum collection).

While for his Antarctica lectures Ford could always rely on his having been a member of the Discovery expedition giving him an ability to speak from direct experience of a part of the world still largely unknown, he added FRGS to his advertising. This gave added cachet to the address. Most importantly, he also had a series of slides to present a visual impression of a continent still largely unexplored.

Later New Zealand career

Gummer and Ford designed some important buildings during the 1920s and 1930s including the Auckland Railway Station and the Dominion Museum in Wellington and Ford wrote a pioneering New Zealand earthquake engineering text (Ford, Reference Ford1926). His architectural views were traditional and, ultimately, he concentrated on the business side of the practice (Lowe, Reference Lowe1998; Wood, Reference Wood2011). He was also involved with the Auckland War Memorial Museum for many years, eventually donating a porcelain collection. Ford clearly had intelligence, energy and the capacity to quickly pick up new skills, which in New Zealand enabled him to ascend to a comfortable middle-class existence and a respected place in professional circles and Auckland society, things that would have been difficult if not impossible to achieve if he had returned to the UK and remained in the RN. He served on the short-lived New Zealand Second Polar Year Committee in 1931–32 and was a Vice President of the New Zealand Antarctica Society founded in 1933. This effectively marked the end of Ford’s Antarctic activities, although during the 1960s and up until his death in 1972 he responded to inquiries about the Discovery expedition. While alive he donated some relicts of the expedition to the Auckland War Memorial Museum. His Antarctica slide collection and other papers were bequeathed in 1972. Ford was proud of his involvement in the Discovery expedition and listed his FRGS along with various architectural memberships in successive editions of Who’s who in New Zealand but was not defined by the public or himself by his Antarctic experiences. For most of his career, he was an architect.

New Zealand established Scott Base as an Antarctic research station in 1957. In 1958, Sir Edmund Hillary reached the South Pole overland (somewhat controversially) as part of Vivian Fuch’s Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (Dodds & Yusoff, Reference Dodds and Yusoff2005). Ford’s membership of Discovery crew was not, however, to be completely forgotten. In 1962, he delivered the Auckland Institute lecture, “To the Antarctic with Scott’s first expedition” at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, 60 years after the events in question. The lecture was illustrated with his original slides. That same year a rocky spur on the Transantarctic Mountains above the Keltie Glacier was surveyed by the New Zealand Geological Survey Antarctic Expedition and named Ford Spur. At 84.85’S, it symbolically surpassed the 82.17’S of Scott’s November 1902 to February 1903 “Furthest South” journey and the subject of so many of Ford’s public lectures.

Lecturing as performance

Ford’s popular lectures may be scrutinised against a “performative triangle,” the “realism” of photography (Nelson, Reference Nelson2000) and Keighren’s (Reference Keighren2008) “standards of trustworthiness.” The interconnections between Ford, his audience and his photographic images, in the absence of direct audience recollection, can be partly discerned from period newspaper accounts. His slides were an essential part of the lecture. He spoke to the audience rather than reading from a prepared script, enabling him to claim that the performance was not a lecture, and his descriptions, triggered by individual slides were rich in imagery. Ford’s fully blown “Furthest South” lecture was firmly aesthetically based, but it was also laced with humour, for instance, his aside that the “head cook was a personage and wouldn’t cook, the second couldn’t, and the result was spoilt meals” (Life in the City, 1905, p.3). His accent [“cultchaw,” “purpoht”] attracted tongue-in-cheek comment in the theatre column of one newspaper to the effect that,

Mr. Ford’s matter was interesting, and if he had told it with fewer plums in his mouth, and less of English cultchaw in his accent, the audience need not have extended their ears quite so terribly. However, by listening intently, they gathered its purpoht and, hung on till the very last word was fired. But the pictures were best of all. (Footlights, 1905, p.16)

If nothing else, this suggests that Ford was not speaking with a decidedly regional UK accent and was perhaps already reinventing himself by escaping from Home class distinctions in the colonies. It may also point to an aspect of the “colonial cringe” whereby having an English accent, actually gave Ford additional credibility in front of New Zealand audiences.

The lantern slides were critical to Ford’s presentation. There was a direct line of engagement between audience and image where Ford acted as a skilled conductor. His presence on the ice and furthermore his participation in the events shown in his slides added to the veracity and authority of his lecture. Linked to the images Ford also discussed other aspects of his experiences observing that, “while the polar voyager becomes inured to the sense of extreme cold, he is never unconscious to it. The intensity of the cold is with him always. It can never be ignored” (In Antarctic Ice, 1905, p.30). But captivating and awe inspiring as some of his lantern slides were, he sought to dispel the impression given by the black and white images that the Antarctic was a “white waste.”

I have seen the most gorgeous colours of the tropics, he says, but nothing there comparable for soft and delicate beauty to the Antarctic lights. Sometimes mountain and pack ice are wrapped in beautiful rose pink – more beautiful than the desert rose of Algiers. Then at sunrise and sunset the great waste is almost bright scarlet. On a clear bright day it changes to the tenderest pale blue (Picturesque Impressions 1905, p.4).

In a later magazine article, Ford (Reference Ford1906, p.223) amplified these impressions, writing of the “beautiful magnetic phenomena of the Aurora Australis” and the “beauties of the pack ice” and how he was “in touch with the deepest and grandest elements in Nature” he also wrote of its silence (Ford, Reference Ford1906, p.224). He further suggested that words would not always suffice, “the antarctic has a majesty not to be described in words. There is something unutterably grand in these vast ranges of snow-covered mountains rising precipitously from the sea to great heights, with peak after peak piercing the highest clouds” (Ford, Reference Ford1906, p.222). His lantern slides could partially fill this gap. It was fascinating and engaging – “Two hours passed, the audience scarce noting” (Antarctic Exploration, 1905, p.5).

Ford’s public lectures in the 1920s were not reported in the same sort of detail in newspapers. They contributed nevertheless to civic culture in a settler society with a slowly emerging sense of identity while still lodged firmly within the British Empire. The Antarctic, the Ross Dependency claimed in 1923, along with US Admiral Byrd’s late 1920s and early 1930s expeditions kept the continent in the news in New Zealand. In the absence of more than a few further expeditions, Ford’s narration and image retained their attractiveness. Even though he was drawing on first-hand events of nearly 25 years previous, the natural history aspect of the talks did not date and now Ford had extra status as a prominent Auckland architect. He gave other public lectures on a range of topics, mostly related to architecture, at this time and in later years.

Ford’s involvement with J. C. Williamson signals that the venues for his lecture were ordinary theatres and halls not the venues of New Zealand equivalents of British literary and philosophical and scientific societies (Keighren, Reference Keighren2008). A few such organisations did exist in New Zealand at the time, notably in the form of the branches of the New Zealand Institute, forerunner of the Royal Society of New Zealand, but Ford’s more general audience was interested in his Antarctic experiences; solitude, grandeur, mystery and terror were the words used by a newspaper reporter listening to his first lecture in New Zealand. His audiences did not require or seek a scientifically based lecture, although sometimes, for instance with respect to the magnetic South Pole, doubtless of particular interest to someone with RN background, he introduced scientific matters. The realism of Ford’s slides and the scale of the icebergs vividly struck his audience, but did not, in contrast to what Nelson (Reference Nelson2000) suggests, lead on to a scientific interpretation; Ford by inclination remained primarily an aesthetic interpreter of the Antarctic environment. After 1906, the link to J. C. Williamson was severed and Ford’s subsequent lectures were given to smaller groups more in the vein of a travel or natural history lecture.

Conclusion

The official and other main accounts of the Discovery expedition are officer and scientist accounts. Ford fills a gap as a member of the crew who leaves a written and pictorial record of the expedition and who lectures on his experiences. This output exceeds in quality and quantity what might have been expected from someone who was the expedition’s Steward. Ford is recognised in the main accounts for his role in managing the ship’s stores. His exactness was well suited to the task (apparent in his water colours and carried over to his later architectural designs). His own sledge journey was written out of Scott’s official account. Ford’s responsibilities kept him close to the Discovery and accordingly, he provides considerable detail about some of the more mundane activities on the vessel and in the immediate environment, including photographing nearby seals, penguins and birdlife. This distinguishes his writing from the “heroic” explorer and more scientific focus of other accounts. At the same time, Ford was moved by the grandeur of the physical environment. His more limited formal education did not impede his ability to produce clear and evocative prose. He had kept a journal since early in his time in the RN. His Antarctic diary informed his lectures, but only fragments of it ever appeared in print. Because of the ephemeral nature of the lecture and Ford’s full diary never having been published, he remains in the shadows as a member of the expedition. As one of the younger men on the expedition, Ford seized the opportunity, capitalised on the original Steward’s shortcomings, and on leaving the RN used what later in the century would be regarded as a degree of “celebrity” to give public lectures, ultimately pursuing a new and rewarding life and professional career in New Zealand. As time passed, he became one of the dwindling numbers of expedition survivors and from the 1960s was in correspondence with those interested in the history of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration.

Ford’s authority as a lecturer rested on his having been a member of the Discovery Expedition, one of only a handful of individuals to have overwintered on the continent. He talked about Antarctica from first-hand experience with the aid of lantern slides. He is not alone in this respect, and this extends to other than Antarctic environments (e.g. Anderson, Reference Anderson2019; Bateman, Reference Bateman2010; Blunt, Reference Blunt1994; Hevly, Reference Hevly1996). Extra standing was conferred by his having been awarded a Polar Medal and an RGS Medal, but it was his FRGS that was most easily added to lecture advertisements that gave added credentialing. That his acting Warrant Officer status was sometimes mistakenly translated by others into his being an Officer on the expedition only added further luster to the event. As a crew member, Ford had limited involvement with the officers’ tasks of command and exploration or with scientists collecting specimens, mapping, measuring and describing their environment. His sledge trip forgotten in the “official record” could be relived each time he lectured.

The “cultural imaginary” of early 20th century Antarctic exploration was played out in Ford’s lectures in images and words. Ford’s photographic endeavours reveal an artistic predisposition, demonstrated in his subsequent architectural career. Some of the subjects photographed were likely constrained and accentuated by his role as Steward which kept him on or close to the Discovery. This included the stark grandeur of the landscapes dominating the humans within it, and similarly he wrote about icebergs largely from an aesthetic point of view. He also showed a considerable interest in the seals, penguins and birdlife, and they feature in a disproportionately large number of his slides.

What of the “Performative triangle” connecting Ford, the images and the audience? Reports of his first well-attended public lecture in Wellington point to a conversational delivery, not overly embellished with Edwardian rhetoric, which went down particularly well with New Zealand audiences. It also seems reasonable to imagine that with experience Ford became more accomplished at delivering his lecture. He did not place himself between his audience and the lantern slide images, but he did interpret and augment what they could see, notably by alerting them to other “senses” not apparent in the black and while images, notably colours and sound. The novelty of the images of a still largely unknown continent added to the occasion which had been given extra prestige by the Premier himself introducing Ford and the presence of other local notables and appreciably adding to “civic culture.” The slides themselves were unquestioned as providing unassailable evidence of the nature of the continent. The poorly attended lecture in Ashburton revealed another type of “performative triangle” when Ford rebuked his audience for not attending in larger numbers. New Zealand audiences, however, remained interested in Ford’s Antarctic experiences for two decades, while Ford himself forged a new career far removed from the RN and Antarctic exploration.

Conflicts of interest

None.