13.1 Urban Governance and Transformations

Urbanization and urban areas are profoundly altering the relationship between society and the environment at accelerated rates, affecting our chances to create livable, sustainable, and just societies worldwide. Urban areas are key sources of resource use and pollutants globally. For instance, they emit up to 70 percent of global greenhouse gas, or GHG, emissions (Romero-Lankao et al. Reference 280Romero-Lankao, Gurney, Seto, Mikhail Chester, Duren and Hutyra2014). However, both resource use and GHG emissions within a city are not often under the remit of local governments; rather, they are the responsibility of national governments, the private sector, and other actors. At the same time, urban populations, economic activities, infrastructure, and services are vulnerable to an array of negative environmental impacts, such as mortality from extreme heat and damages from hurricanes, storm surges, and flooding. Furthermore, environmental issues are cross-scale issues. This means that urban areas are affected by actions beyond their boundaries, and urban uses of natural resources, GHG emissions, and risks create effects far outside the demarcations of city limits (see Chapters 3 and 4). Hence, these issues are not only local governmental concerns, but require a diversity of actors across sectors and jurisdictions to network and create coalitions for climate and environmental governance to sustainably manage the use of water, energy, and other resources; to mitigate GHG emissions; and to adapt to and mitigate environmental risks.

The complex nature of environmental and climate challenges associated with the current Anthropocene era cannot be suitably dealt with by the modest and fragmented responses that are most common in urban areas worldwide. Incremental reform may prove inadequate; instead, we may require transformative responses that alter core elements of urban systems, such as energy, water, and land-use regimes and influence multiple interconnected domains, such as sociodemographics, economics, technology, environment, and governance itself, with their basic power relations, worldviews, and market structures (Park et al. Reference Park, Marshall, Jakku, Dowd, Howden, Mendham and Fleming2012). The study of transformation in response to environmental change is established among scholars and communities of practice. However, it is critical to focus on the value this knowledge can add to existing environmental policy and governance in urban areas, which are both key drivers of environmental change and sources of solutions. Transformation is a concept deeply embedded in the human narrative. It conveys the notion of systemic, essential, and radical change that can affect an array of fundamental urban socioecological system domains such as sociodemographics, the economy, technology, ecology, and governance regimes (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hahn, Olsson and Norberg2005; Romero-Lankao and Gnatz Reference Romero-Lankao and Gnatz2013; Geels and Schot Reference Geels and Schot2007; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Schulz, Vervoort, van der Hel, Widerberg, Adler, Hurlbert, Anderton, Sethi and Barau2016). For instance, can the concept of transformation play a normative role in helping us purposefully move cities towards sustainability and resilience? Or should it be confined to an ex-post analysis of change in cities? And why should we focus on cities?

Many actions and strategies will be needed to trigger such transformative processes, from coordinated action by governments to innovation in the private sector, experimentation, and pressure from civil society. This is where the questions around the role of governance in shaping transformations towards urban sustainability and resilience become paramount. Are we mostly interested in understanding the links between governance and the politics of change? Are we looking into governance as part of the problem and engaging with transformations in existing city governance regimes? Is our emphasis on governance that creates the conditions for transformation to emerge, or on actively fostering transformation processes? (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Schulz, Vervoort, van der Hel, Widerberg, Adler, Hurlbert, Anderton, Sethi and Barau2016) What exactly must be transformed; why, how, by whom, and in whose interest; and, what factors drive or trigger the necessary transformations?

Rather than suggesting the most appropriate range of responses needed to achieve transformational actions and policies, this chapter sets the stage for Part III and builds on previous work to identify both opportunities and challenges that city officials and private and civil society actors face in their efforts to develop governance solutions that support sustainable and resilient urban development. This chapter will start with the definition of key terms (for example, urban governance), and of main approaches to the governance factors shaping change towards more sustainable and resilient development pathways (Section 13.2). Many actions and strategies have been introduced to address sustainability and resilience concerns (for example, urban water management and transportation). In Section 13.3, we will briefly describe different types of actions seeking to mitigate or prevent risk and to adapt to existing and possible environmental threats and disruptions. Mitigation refers to actions aimed at reducing resource use and environmental impacts and risks; adaptation refers to actions aimed at managing these impacts, before or after they are experienced (Field et al. Reference Field, van Aalst, Adger, Arent, Barnett, Betts, Field, Barros, Dokken, Mach, Mastrandrea and Bilir2014). The following sections describe the nature of the actor-networks involved in designing and implementing actions (Section 13.4), and the opportunities, barriers, and limits that multilevel governance poses to local climate and environmental policy (Section 13.5).

13.2 Multilevel Governance and Transformations

Interest in transformations towards sustainability and resilience has grown considerably in recent years among researchers and communities of practice globally. For instance, it has been addressed in debates around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, see Part II). It is one of the themes of Future Earth’s Sustainability Research Platform. And it has become a key component of IPCC assessment efforts (Field et al. Reference Field, van Aalst, Adger, Arent, Barnett, Betts, Field, Barros, Dokken, Mach, Mastrandrea and Bilir2014). Urban governance and politics are critical to understanding and shaping these transformations for many reasons: Governance can offer both barriers and opportunities to transitioning towards urban sustainability and resilience; further, these transformations are inherently contested and political (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Schulz, Vervoort, van der Hel, Widerberg, Adler, Hurlbert, Anderton, Sethi and Barau2016; Romero-Lankao et al. Reference Romero-Lankao, Gnatz, Wilhelmi and Hayden2016).

Urban governance takes place within broad socioeconomic and political contexts, with actors and institutions at multiple scales shaping the effectiveness of urban actions and responses. In particular, urban environmental governance comprises formal and informal rules, rule-making systems, and actor-networks across sectors and jurisdictions, both in and outside of government, that are established to steer cities towards sustainable resource management, environmental change mitigation and adaptation, and transitions along alternative development paths (Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Betsill, Gupta, Kanie, Lebel, Liverman, Schroeder, Siebenhüner and Zondervan2010).

Below, we review the main strands of literature that engage with the influence of governance in actions and strategies seeking to transition urban areas towards more sustainable and resilient development pathways. These include theories of sociotechnical transitions (Geels and Schot Reference Geels and Schot2007; Rutherford and Coutard Reference Rutherford and Coutard2014) and socioecological transformability, political ecology perspectives (for example, sustainability pathways and transformative adaptation; Lawhon and Murphy Reference Lawhon and Murphy2012) and a growing body of scholarship on experimentation. These approaches provide significant, albeit partial, visions of urban transformations that aid in the understanding of the barriers and opportunities associated with the practice of urban sustainability and resilience transitions. For instance, sociotechnical transitions theory sheds light on some of the processes shaping changes in environmental management regimes, while political ecology approaches illuminate the influence of power relations among actors with different values and interests in shaping social change.

13.2.1 Sociotechnical and Socioecological Theories of Transformation

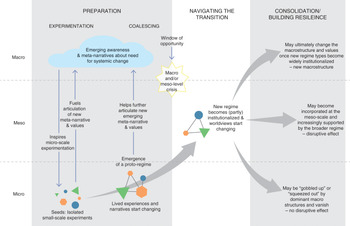

Sociotechnical transitions theories, also called STTs, examine the multilevel processes through which socioecological and technical systems experience transformations. STTs define transformations as shifts to systemically different sociotechnical regimes of resource use and relationships with the environment (Smith and Stirling Reference Smith and Stirling2010; Geels and Schot Reference Geels and Schot2007; Rutherford and Coutard Reference Rutherford and Coutard2014). Transformation is conceived as a series of far-reaching changes along different domains: technological, governance, economic, sociocultural, and environmental. It includes a broad range of actors and unfolds over substantial periods (50 years or longer, for example). Examples include the transition from cesspools to sanitation, from telephone to cellphone, and from internal-combustion to electric vehicles. Within the transitions literature, there is a fast-growing body of work on urban transformations. This work has evolved from situating “urban” simply as the context of new empirical examination of transition experiments to investigating urban patterns of transformation as unique to the understanding of contemporary transitions.

A sociotechnical regime organizes social practices and structures relationships among private, governmental, and nongovernmental actors, whose understandings of priorities, appropriate actions, and technologies are intertwined with the expectations and skills of users, with institutional arrangements, and with physical infrastructures providing energy, water, and materials. A regime is “dynamically stable” and imposes a logic and direction for incremental sociotechnical and socioecological change along established pathways of development, which, in turn, create path dependency or lock-in. Electricity and urban water management provide conspicuous examples of lock-in due to the endurance of their material structures and the sturdy techno-institutional interrelationships associated with them. While regimes are dynamically stable, they are constantly subject to drivers and pressures that can lead to their destabilization and transformation. Some of these drivers and pressures are:

Innovations and experimentations, or proactive changes such as new technologies, social experiments, and governmental or grassroots initiatives. Innovations can contribute to structural or fundamental changes in cultures, structures, practices, and relations between actors. Experimentation can nurture new technologies and create new institutions and new governance processes.

Conflict and contestation of actions around access to, use of, or redistribution of natural resources, assets, and decisions, with resulting social and environmental implications (for example, on water quality and availability, social inequality, and livelihoods); and,

Environmental impacts and triggers in the form of natural resource depletion and scarcity, disasters, or changes in risk tolerance resulting from shifts in economic, cultural, and/or political dynamics (Romero-Lankao and Gnatz Reference Romero-Lankao and Gnatz2013).

Governance and governmental policies frequently exert an influence on transitions through transition management, which includes insights from complex systems and governance approaches (Loorbach and Rotmans Reference Loorbach and Rotmans2010). Transition management conceives socioecologic systems, such as urban areas, as complex and adaptive. Management in this context appears as a reflexive and evolutionary governance process (Markard et al. Reference Markard, Raven and Truffer2012).

Socioecological systems literature has engaged with the question of how adaptive governance can enhance or foster adaptability of cities as socioecological systems. The concept of resilience, originated in ecology, is fundamental to this approach, which focuses on how much stress and disturbance an urban system can adapt to while remaining within critical thresholds before it moves to another regime (Carpenter and Brock Reference Carpenter and Brock2008). In this perspective, urban resilience is conceived as the ability of complex socioecological systems, such as cities and urban communities, to change, adapt, and – crucially – to transform in response to both internal and external stresses and pressures (Davoudi et al. Reference Davoudi, Shaw, Jamila Haider, Quinlan, Peterson, Wilkinson, Fünfgeld, McEvoy, Porter and Davoudi2012; Ahern Reference Ahern2011). Governance of cities plays two roles within this approach. In the first one – governance for navigating change – both short-term and long-term actions seek to shield cities from hazards and disruptions, and to provide urban communities and actors with the capacity to respond to change and uncertainty. In the second role – governance for transformation – actions and policies are envisioned and implemented that create new urban systems when current conditions render existing systems unviable (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hahn, Olsson and Norberg2005).

13.2.2 Experimentation

As noted above, innovations or experimentations can destabilize sociotechnical regimes and drive transformative change. Experimentation is a process for instigating sustainability transitions, particularly within cities, with many cases showing impacts on governance dynamics, for example from experimentation in the urban water sector (Ferguson et al. Reference Ferguson, Frantzeskaki and Brown2013; Poustie et al, Reference Poustie, Frantzeskaki and Brown2016), in urban mobility (Späth and Rohracher Reference Späth and Rohracher2012), and in urban energy (Castan-Broto and Bulkeley Reference Castan-Broto and Bulkeley.2013). Experimentation includes lighthouse projects that have great symbolic value for urban planning and development, such as the Floating Urbanization pilot project, the Floating Pavilion in the City Ports of Rotterdam, or the eco-district Hammerby in Stockholm. Experimentation can come in the form of open-ended labs that test, or, cocreate new approaches or solutions to urban challenges, such as increasing community cohesion or facilitating urban regeneration through coproduced urban agendas, as well as through urban projects that can set transformative processes in motion. Experiments can be facilitated by local governments, established by public-private partnerships, or self-organized by civil society and citizens themselves, from the grassroots. Recent scholarship showcases the importance of creating both physical and institutional space for experimentation processes to take place (Castan-Broto and Bulkeley Reference Castan-Broto and Bulkeley.2013; Bulkeley et al. 2016; Frantzeskaki et al. Reference Frantzeskaki, Wittmayer and Loorbach2014, Reference Frantzeskaki, Castan-Broto, Coenen and Loorbach2017; Nevens et al. Reference Nevens, Frantzeskaki, Loorbach and Gorissen2013; Loorbach et al. Reference Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and Avelino.2017).

Experimentation has, in many cases, evolved into the preferred governance tool for addressing complex urban problems. This may explain the observed proliferation of experimentation as a way of governing cities for climate change across Europe, Latin America, and Asia. In particular, the empirically based research on sustainability transitions, focused on smart cities, resilient or sustainable cities, and water-scarce cities, showcases that there is merit in trial experiments and new solutions in cities. These processes create a base of evidence for effective urban solutions that tackle local manifestations of climate change. Experimentation is not limited to climate change concerns; it can also address issues of inequality and accessibility to health care, services, and education. Future urban research will need to examine how experiments addressing urban sustainability challenges contribute to urban agendas for development and what impact they have on contemporary urban dynamics in ecological, social, economic, and political domains of cities.

While there is a recognized need for new approaches to deal with political and social challenges to secure sustainable and livable urban futures, experiments and new forms of governance can enable positive transitions to urban sustainability. However, these innovations are not always welcomed by communities or by political institutions. The controversies, contestations, and conflicts that come along with experimentation are also important ingredients in the governance of urban transformations (Chapters 14 and 15). Alongside these tensions, the current manifestations of governance practices and processes need to be revised and adapted to allow institutional space for actors driving urban transformation and experimentation, which act as lighthouses for new pathways to sustainability (Chapter 16).

13.2.3 Critical Theories of Transformation

Sociotechnical transition theories have helped elucidate the barriers to and options for transformations through the interplay between governmental and private actors, social practices, and institutions. By focusing on urban resilience as an ability to bounce forward, socioecological system theories have shed light on cities’ and urban actors’ capacity to change, adapt, and – crucially – to transform in response to hazards and disruptions. However, sociotechnical transition theories, which have focused mostly on Europe and the United States, have little to say about how transitions may play out differently in the cities of middle- and low-income countries (Bulkeley et al. Reference 278Bulkeley, Castán Broto, Hodson and Marvin2010). Similarly, scholars have suggested that socioecological system theories cannot be uncritically applied in the process of trying to understanding how social domains function. In this view, urban groups and communities have the capacity to cope, or adapt, to stresses and disruptions, but these capabilities are also shaped by social, political, and cultural processes. Socioecological approaches have often been criticized for being deterministic and for omitting the role of different levels of agency and power in creating or preventing transformational movement away from previous system phases and cycles. As illustrated by many scholars, pro-growth coalitions, unabated by powerless local authorities and civil society organizations, pose challenges to navigating towards more sustainable and resilient pathways of urban development (Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, Manuel-Navarrete and Robinson2016; Romero-Lankao et al. Reference Romero-Lankao, Hardoy, Hughes, Rosas-Huerta, Borquez and Gnatz2015).

To address these concerns, sustainability pathways approaches seek to understand transformations in ways that are sensitive to the deeply political, contested nature of urban sustainability and resilience issues (Robinson and Cole Reference Robinson and Cole2015; Bendor et al. Reference Bendor, Anacleto, Facey, Fels, Herron, Maggs, Peake, Robinson, Robinson and Salter2015). This is achieved by taking into consideration diverse views of and aspirations for what desirable sustainable solutions are, and consider mechanisms to navigating trade-offs and side effects of the proposed transformative solutions. Cultural values, as well as economic and political considerations, play key roles in defining sustainability and resilience goals; acceptable risks to livelihood, property, and other things urban actors value; and outcomes. Because this perspective assumes that both sustainability and resilience are contested, dynamic, and uncertain, it puts institutions and values at the center of efforts to understand and navigate transformations towards sustainability and resilience in cities.

Political ecology scholars have criticized STTs as providing a narrow lens for viewing the processes shaping (limiting, fostering) change, with their emphasis on infrastructures, users, experiments, and technological innovations (Lawhon and Murphy Reference Lawhon and Murphy2012). Political ecology scholars suggest that STTs do not take into consideration that corporate and state leaders, scientists, and innovators of all sorts do not always hold progressive, fair, and/or environmentally friendly values and interests. For political ecology scholars, both cooperation and conflict are inherent features of decision-making in general, and transition management in particular (Lawhon and Murphy Reference Lawhon and Murphy2012). This is so because environmental policies that can aid in transition essentially revolve around who benefits and who bears the risks of actions, with a clear set of winners and losers. For example, large-scale power generation and trans-basin water imports can be a desirable means of dealing with energy and water scarcity for some urban elites and benefiting populations within a city, but these changes can be highly undesirable for people and places that bear the stress and hardship implied by these actions. Therefore, it is essential to ask, in the governance of any transition process: what actors and places are at stake; with whom and where power resides; what social and environmental consequences of decision-making are at play; and whose voices and narratives remain unheard?

13.3 Responses and Actions Developed and Implemented in Urban Areas

Many actions are being developed and implemented worldwide with the purpose of providing urban sustainability solutions that address issues such as water and energy management, flood mitigation, other environmental protections (air quality), and cleaner and affordable transportation systems, to name a few. It is increasingly clear that ensuring the future sustainability of the planet requires that these strategies and plans address the consequences of a changing and uncertain climate. Such impacts manifest differently, are experienced uniquely in urban areas (and, at even finer resolutions, are experienced differently among different urban populations), and must be dealt with accordingly – in specific ways that are embedded in the sociopolitical and economic realities that characterize an urban space at local scales.

Urban climate responses include climate change mitigation and adaptation actions, also called resilience actions. These responses range from short to long term, from local to regional, and vary widely in their effectiveness and outcomes. They also include the following domains:

1. Understanding the problem: For instance, if the goal is to mitigate GHG emissions, an inventory will provide a baseline against which mitigation targets can be assessed. A focus on reducing vulnerability will require assessments of the damage to property, disease, and loss of livelihoods that urban populations may face under a changing climate.

2. Incremental responses: For example, mitigation actions focused on municipal government buildings and vehicle fleets are the most common approaches used by city officials worldwide. It is also very common among cities to start with adaptation actions that build on ongoing disaster risk management (Barrero Reference Barrero, Bass, Reid, Satterthwaite and Steele2013).

3. Broader, longer-term responses that seek to change urban form, institutions, and social practices are equally important. Examples of these include:

a. Infrastructural investments that: (i) decrease vehicle kilometers traveled, foster mixed-use development, improve destination accessibility, and reduce distance to transit. These goals are achieved by concentrating development and, hence, reducing energy use by vehicles and the stress associated with driving (Hamin and Gurran Reference 279Hamin and Gurran2009); (ii) discourage growth in risk-prone areas and protect or restore ecosystem services such as water infiltration, flood protection, and temperature regulation. These actions may help create synergies between mitigation and adaptation by influencing resource use and emissions, and by fostering the resilience of people and places;

b. Actions that build capacity by enhancing the resources and options afforded to populations from diverse socioeconomic groups to use environmentally friendly sources of energy, food, or water, and to adapt to environmental threats, such as those induced by climate change;

c. Actions that reduce exposure to environmental and climate threats, or that mitigate risk (such as dikes and barriers, or multiple-use green ways).

4. Transformative responses that create shifts in energy, water, transportation, and land-use regimes, growth ethos, production and consumption practices, and worldviews(Field et al. Reference Field, van Aalst, Adger, Arent, Barnett, Betts, Field, Barros, Dokken, Mach, Mastrandrea and Bilir2014). Some of these actions target the underlying drivers of resource use, emissions, and vulnerability, such as a shift from centralized electricity fueled by fossil fuels to decentralized, rooftop solar energy, or a focus on integrating environmental and local disaster risk management concerns with an inclusive and pro-poor urban development agenda, as exemplified by Manizales (see Chapter 15). As such, transformative actions hold the potential to promote a more systemic shift towards sustainable and resilient urban development (Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Burch, Kristensen, Robinson and Dale2014; Burch et al. Reference Burch, Shaw, Dale and Robinson2014).

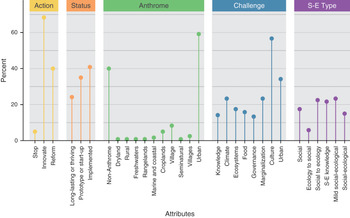

This section reviews some of the climate responses (with a focus on adaptation or resilience efforts) that occur in cities of multiple regions and typologies, setting the stage for the following section, which analyzes the governance and decision-making processes and structures that have enabled – or constrained – their development and implementation. Our brief description of these responses provides useful entry points to juxtapose global problems and local solutions or vice versa, and the multiscale governance processes involved. Such actions are diverse in nature and scope, can range from small- to larger-scale efforts, and include a variety of tools and approaches for implementation.

Actions to increase adaptive capacity to threats – including, but not limited to, climate-induced flooding from heavy rainfall events or storm surges, heat waves, or water scarcity and drought – ultimately affect urban areas and populations, but how and at which scale they are developed can vary. Urban households and communities, for example, have long implemented measures to adapt to changing environmental conditions and specific threats by drawing on local knowledge, consistent with sociocultural practices. These are numerous and particularly common in low-income and developing nations where large-scale poverty exists and the institutional capacities to adapt are much weaker. Examples of adaptation practices include innovation in water collection and retention in times of drought, changing precipitation patterns, or saline intrusion; adaptation to agricultural practices through altering the timing and types of crop grown; tree and vegetation planting for storm water absorption or heat mitigation; and the construction of pole or stilt housing in flood prone, high-risk urban areas. It is still unclear how to scale up adaptation actions and institutionalize them within local and regional policies, and in doing so, if the adaptation actions are appropriate for these larger scales. Conversely, more comprehensive and thoughtful decision-making efforts that include a range of urban stakeholders can also reduce cases of maladaptation that occur due to ad hoc coping strategies and actions that sometimes conflict with broader socioeconomic and environmental conditions (Schaer Reference Schaer2015).

Adaptation to climate threats is as complex as the urban system, and it is proportionately challenging to develop and implement at the city or regional level, requiring approaches that are multidimensional and include actors at multiple scales. Citywide adaptation and risk mitigation responses often employ a range of approaches that can include either soft or hard infrastructure measures, or a combination of both, to adapt to specific climate change impacts. For example, to mitigate effects of the microclimate in cities (such as urban heat island), cities are beginning to utilize cool pavements (light-colored surfacing or permeable pavements); cool roofs (often categorized as “white,” “blue,” or “green” roof strategies to differentiate the approaches); increasing vegetation abundance; and reducing waste heat (Gartland Reference Gartland2012). Coastal cities, often plagued by extreme flooding due to sea level rise, storm surges, and hurricanes, may utilize hard engineering approaches such as sea walls or levees, or turn towards nature-based solutions or ecosystem-based adaptations, including restoring natural wetlands or mangrove ecosystems to buffer the effects of extreme wind and flooding. These “softer,” ecosystem-based approaches, which are viewed as more cost efficient, comprehensive, and multifunctional by design, have gained popularity as a response to the negative associations of “hard” adaptations, which are prone to being inflexible, costly, and inadequate for addressing a range of interests or perspectives of the problem the action seeks to address.

13.4 Multilevel Actor-Networks

As indicated in our introduction, environmental – and particularly climate – changes are socially and environmentally pervasive phenomena. Therefore, they challenge actors from different sectors and jurisdictions to create multilevel governance networks and coalitions. Rather than being homogeneous, these groups frequently hold different values and interests, create shifting alliances, and have varying levels of power. This heterogeneity poses challenges for coherent and legitimate urban climate change governance, as actor-networks play multiple and changing roles in urban environmental governance: some provide energy, food, and water resources; others function as facilitators of interactions within and between cities; and yet others define dominant environmental discourses more broadly. The climate change arena offers examples of the relevance of actor-networks, with many urban actors independently committing to mitigation and adaptation, even in the absence of national climate change policies. Furthermore, some actors from the private sector are addressing climate change within their own companies, or are forming partnerships to achieve a common goal. The myriad of actors involved means that, in many cases, suboptimal outcomes will be created.

Actors and their governance arrangements operate in a complex web of interactions, a pattern that had been captured using the notion of interplay. The concept of interplay sheds light on the interdependence of institutional arrangements at varying (vertical interplay) and similar (horizontal interplay) levels of organization (Young Reference Young2002). These interdependences create policy challenges. The actors involved in the governance of environmental change in cities frequently have very diverse mandates, operate at different time scales, and use different expertise or understanding of the climate issue. For instance, in Cape Town, South Africa and Mexico City, Mexico, officials have pursued climate change mitigation, but the effectiveness of their actions has been constrained by differences in ruling parties and political cultures that constrain structured interactions and collaborations (Holgate Reference Holgate2007; Romero-Lankao Reference Romero-Lankao2007). In larger urban areas as diverse as New York, Mexico City, Dakar, and Buenos Aires, which comprise two or more local and state authorities, each authority can act only within its boundaries. This means that the overall impact of their policies may be limited unless there is horizontal collaboration among neighboring authorities, or an overarching strategic metropolitan authority exists to ensure citywide action (Solecki et al. Reference Solecki, Leichenko and O’Brien2011).

For diverse reasons frequently related to authoritarian culture or jurisdictional boundaries, environmental authorities seldom interact with development authorities, and tiers of government seldom collaborate. Priorities in urban planning are dominated by economic concerns, with environmental concerns frequently taking the back seat. As a result, the design and implementation of a sustainability plan depends on strong administrative leadership, as well as on whether the commitment of the various implementing actors is guaranteed and how long-term decisions are made.

Actor-networks have appeared that link city officials, private sector actors, community organizations, and academics, to create more coordinated, international approaches to sustainability and resilience challenges such as those posed by climate change (Betsill and Bulkeley Reference Betsill and Bulkeley2004; Andonova Reference Andonova2010). ICLEI’s Partners for Climate Protection program and the C40 are examples of increasingly important global networks that influence responses to sustainability challenges (Andonova Reference Andonova2010) by providing financial resources as well as opportunities for learning and sharing experiences, tools, and lessons. Notwithstanding the promise of these networks, the interactions among participant actors and the effectiveness of their actions are constrained by the wide differences in jurisdictional remit, organizational culture and structure, and political context.

Actors and actor-networks vary in the extent to which they can influence the framing of sustainability issues, the governance of climate and environmental change, and the resources to implement actions. This inequality is best illustrated by the fact that those urban populations that are most vulnerable to climate change are often not those who are responsible for the majority of GHG emissions. Climate and environmental change also have the potential to exacerbate existing societal inequalities in terms of income distribution; access to resources and options to pursue livelihoods; and capacity to effectively respond to environmental and social threats (Romero-Lankao et al. Reference Romero-Lankao, Hardoy, Hughes, Rosas-Huerta, Borquez and Gnatz2015). A growing body of research reveals that climate and environmental change governance strategies and actions can create or recreate (un)just decision-making processes and outcomes or result in an (in)equitable distribution of risks and resources (Hughes Reference Hughes2013).

13.5 Multilevel Governance Poses Opportunities and Barriers to Local Policy

While city officials are at the forefront of acting on global environmental challenges such as climate change, existing scholarship points to a variety of opportunities, barriers, and limits to the implementation of coordinated and cross-sectoral actions. Many environmental and climate plans need to be holistic and comprehensive; yet, the siloed, shorter-term nature of decision-making poses political, cultural, and professional challenges to horizontal and vertical coordination between actors, who usually are scattered across sectoral agencies, utilities, and city-administrative departments (Kern et al. Reference Kern and Alber2008), and work on short planning horizons.

Scholarship has also found that the expertise required to address sustainability challenges frequently remains concentrated in environmental departments. This makes cross-sectoral and cross-jurisdictional coordination within the organizational hierarchy of city government particularly challenging, as environmental bodies usually have limited remit over and capacity to implement actions in key development areas, such as energy, transportation, land planning, and finance (Kern et al. Reference Kern and Alber2008; Romero-Lankao et al. Reference Romero-Lankao, Hardoy, Hughes, Rosas-Huerta, Borquez and Gnatz2015).

Fragmentation in governance systems is driven by more than the physical separation of actors. The implementation of climate and environmental policies is also constrained by a multitude of formal and informal institutional barriers, such as the varied visions, values, interests, and decision-making power of involved actors (Agrawala et al. Reference Agrawala, Carraro, Kingsmill, Lanzi, Mullan and Prudent-Richard2011). Addressing fragmentation as a cross-sectoral planning concern is fundamental if unwanted trade-offs are to be avoided and potential synergies created (Wejs Reference Wejs2014).

Other factors – such as leadership, legal frameworks, scientific information, leadership, the ability to self-organize and mobilize knowledge, and support for the implementation of sustainable solutions – also shape urban actors’ capacity to implement effective actions. While the influence of each factor varies with context, a key area for future analysis are the conditions under which the inadequacies of different combinations of factors function as barriers to effective urban governance. Here, we will briefly touch on some of these.

The legal context in which urban governance takes place plays a key role in determining the extent to which climate and environmental actions, regulations, and programmatic priorities are legitimized, incentivized, prioritized, or demonized. Legal frameworks can also mediate the relationship between decision-makers, the private sector, and the broader public as they provide political structures (or not) for participatory planning and decision-making according to prevailing political norms and cultures. For instance, absent or inappropriate laws dealing with climate adaptation and mitigation can be a hurdle to investments in “climate-proofed” technologies or warning systems. However, it can take a lot of time and energy to change legal frameworks, as this entails complex negotiations across sectors and national to local political levels of decision-making.

The creation of and access to new, city-specific, socially relevant scientific information and local knowledge is fundamental for effective decision-making, particularly in the arena of climate change, where climate projections, GHG inventories, and vulnerability assessments are vital for setting baselines against which progress towards mitigation and adaptation targets can be evaluated.

The availability, communication, and use of information are essential for effective governance. These are not mere technical exercises of collection and insertion of information into the policy process; rather, they are politically determined by power relationships between levels of government, and between government, the private sector, and grassroots actors (Romero-Lankao et al. Reference Romero-Lankao, Hardoy, Hughes, Rosas-Huerta, Borquez and Gnatz2015). Problems of access to usable information are particularly substantial. For instance, an international survey on climate change policies shows that, for 40 percent of surveyed cities, lack of information on the local impacts of climate change is a major challenge to climate change planning and implementation (compared to the 27 percent who report being challenged by a lack of data on GHG emissions)(Aylett Reference Aylett2013a).

Behind the efforts of many cities that are taking steps to address climate change and other sustainability concerns lies the work of leaders, often termed policy champions, who frame climate and other concerns as policy issues and put them onto the political agenda (Betsill and Bulkeley Reference Betsill and Bulkeley2007). Effective leadership strategies comprise the capacity to leverage resources from national and international networks, to create and promote the right framings of complex issues (such as climate mitigation as a means to save money and promote green growth), to create collective consensus, and to institute a shared understanding about the policy direction of a city (Cashmore and Wejs Reference Wejs2014). For instance, scholarship has found that leadership from a mayor, from senior elected officials, or from senior managers is a fundamental enabler of successful climate mitigation strategies (Aylett Reference Aylett2013b). However, for the leadership of individuals to persist, it must be complemented by legal and regulatory changes, by investments in institution building (Hughes and Romero-Lankao Reference Hughes and Romero-Lankao2014), and by a strong civil society (see, for example, Manizales).

13.6 Concluding Remarks

While local governments face many obstacles, they also possess a variety of instruments and policy options for governance, such as land-use planning, transportation systems, building codes, and closer ties to constituents working on the ground. These instruments can help strengthen and trigger action by other levels of government and by private and civil society actors. The level of independence and capacity to govern sustainability and resilience varies across urban areas, but there are still many potential and often untapped possibilities available to urban actors to create effective actions. Urban actors vary in their levels of leadership, access to information, legal mandates, and financial resources. Thus, most innovative approaches will unavoidably need to consider both bottom-up and top-down strategies that can help nurture innovations and experiments to achieve sustainable, effective, and fair urban environmental governance.

The remaining chapters in this section look closely at the governance of environmental change and transformations through different forms of experimentation. They examine the actors driving experimentation to shed light on the conditions, momentum, and institutional contexts in which experimentations operate and how they affect the dynamics of urban change. The authors also engage with the conflicts and contestations arising from dominant interests vested in space accessibility and use in cities, all of which are related to different narratives and perceptions about what desirable and inclusive development looks like in cities.

14.1 Introduction

Civil society’s current engagement in providing and fostering sustainability practices and services illustrates that civil society’s role has expanded beyond advocacy, and that some civil society organizations aim to address the challenge of inclusivity via sustainability innovations. While some civil society organizations may provide basic services that are no longer met by a changing welfare state, others may play a critical role in changing unsustainable social, ecological, economic, and cultural patterns. In part, the different configurations of civil society visible today have emerged in response to social movements, and grassroots initiatives (Tomozeiu and Joss Reference Tomozeiu and Joss2014; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Goodwin and Cloke2014; Warshawsky Reference Warshawsky2015).

Civil society organizes itself in collectives, networks, and nested hubs; mobilizes resources (people, ideas, and funds); and arrives to the wider public through its attempts to put sustainability into practice. For those affected by significant urban challenges, who thus become interested in transforming our cities and societies district by district and community by community, the sense of change that civil society brings can often be seen as a sign of hope that humanity can, collectively, steer away from a deeper crisis or trap. But at the same time, the activities of civil society can create systems where governments can avoid or limit their responsibility in taking daring action to deal with the structural, persistent problems behind these unsustainability crises.

We follow Androff (Reference Androff2012) and Belloni (Reference Belloni2001) in understanding civil society as a broad notion, encompassing grassroots organizations, community-based organizations, advocacy groups (such as NGOs), coalitions, professional associations, and other organizations that operate between the state, individuals, and the market. This heterogeneity means that civil society includes various institutional logics, and it crosses the boundaries between formal and informal, public and private, for-profit and nonprofit. With civil society’s initiatives and social innovation networks proliferating across Europe, it is relevant to consider what is understood by civil society, its role in sustainability transitions, and how this role evolves and changes in different socioeconomic and socio political contexts, across sectoral domains (such as energy, food, mobility, built environment, and education), and across spatial scales (local, regional, national).

Sustainability transitions are about deep, radical change towards sustainability in ways of thinking, doing, and organizing (Frantzeskaki and de Haan Reference Frantzeskaki and de Haan2009), as well as in ways of knowing and relating (Loorbach et al. Reference Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and Avelino2017). As such, the roles that actors assume and actively pursue in the course of a sustainability transition relate to their capabilities to mobilize resources and creativity and to exercise power for transformative action (Wittmayer and Rach Reference Wittmayer and Rach2016). Current sustainability transitions research has identified that not only is the role of civil society changing, but so are the forms of civil society participation in such transitions. Specifically, the adoption of new roles for civil society actors has led to a transformation of their relationships and forms of engagement with other actors (state actors, market-based actors, and so on). However, in the field of sustainability transitions research, studies on civil society have mostly been focused on the phenomena of community energy (Seyfang et al. Reference Seyfang, Park and Smith2013, Reference Seyfang, Hielscher, Hargreaves, Martiskainen and Smith2014; Hargreaves et al. Reference Hargreaves, Hielscher, Seyfang and Smith2013; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Hargreaves, Hielscher, Martiskainen and Seyfang2015) and the role of civil society and social movements in energy transitions more generally (Smith Reference Smith, Verbong and Loorbach2012, Seyfang and Haxeltine Reference Seyfang and Haxeltine2012).

Invigorating the role of civil society in sustainability transitions in sectors other than energy will further contribute to clarifying the importance of such sectoral contexts and add to debates on human-environment interactions in sustainability science. With civil society encompassing and representing a wide array of interests, values, and behaviors, a further examination and conceptualization of its evolving roles is needed. This will shed light on the social and economic dimensions of sustainability, as well as uncover the tensions between these and the environmental dimension of sustainability at local and global levels (Miller Reference Miller2015).

14.2 The Nature of Civil Society

If we are to understand how civil society develops and how it participates in sustainability transitions, we need to have a clearer articulation of what civil society is. Some argue it encompasses grassroots and community-based organizations, advocacy groups (such as NGOs), coalitions, professional associations, and other organizational forms (Androff Reference Androff2012; Belloni Reference Belloni2001); for other authors in sustainability transition studies civil society refers to all organizations that are not part of the state. One thing that is agreed in the literature is that the state and civil society are different, with civil society being autonomous from the state. The border between the two is not a “hard” border, meaning it is sometimes difficult to decide whether an organization is part of civil society or the state. In some cases, civil society confronts the state (therefore NGOs are sometimes described as civil society; think, for example, of Greenpeace campaigns against deep drilling or nuclear power stations), while in other cases, civil society works alongside the state (for example, in the areas of health). A more recently expressed view is that civil society can be understood as a battleground where those competing for power (both the state and civil society organizations) confront each other. At the next level down, a battle for hegemony also takes place within civil society organizations. As Räthzel et al. (Reference Räthzel, Uzzell, Lundstrom and Leandro2015: 160) write, there is a need “to investigate civil society as a ‘force-field’ in which multiple inter- and intra-relationships interact. While state and civil society organizations may oppose each other, and occupy dual positions in the space of civil society, they are present within each other.”

The discourses and practices of community-by-community transformation performed by civil society hold the potential to consider afresh how civil society can initiate and support sustainability transitions while responding to citizen demands for more direct participation in decision-making and more control over defining collective courses of action. We argue that civil society performs a new function in society: civil society is altering deep-seated societal values and beliefs in urban areas towards more sustainable ones, creating and establishing social-ecological and economic literacy and putting knowledge into action for sustainability (Moore and Westley Reference Moore and Westley2011). Such profound change creates the conditions for demand and acceptability of sustainability policies.

14.3 The Roles of Civil Society in Urban Sustainability Transitions

The roles of civil society and the ways in which it interacts with other actors are diverse. In order to capture the recent shifting roles and new forms of civil society, we base our analysis on empirical case study work about civil society in urban sustainability transitions from five research EU-funded projects: ARTS, GLAMURS, GUST, InContext, and TRANSIT. Researchers across these five European research projects convened in a workshop in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, to investigate the role of civil society in sustainability transitions. During the workshop, a wide diversity of empirical cases also informed the discussion and deepened the questions on how to systematically conceptualize the roles of civil society in sustainability transitions and how to search for new evidence.

The case presentations and debates at the workshop allowed researchers with an in-depth knowledge of specific case studies to identify the recurrence of three different roles civil society organizations play and three categories of dangers they face in their interactions with state institutions and actors. This initial inductive analytical framework was then used to orient a thorough literature review, intended to systematize a larger pool of analyzed cases in urban sustainability transitions in Europe. The review covered articles from 2010 to 2015, along with some key additional references from earlier years. Even though many publications were identified (860 papers in total) and thoroughly reviewed, in this chapter, we emphasize those that take a critical perspective on the interactions and interdependencies between civil society and urban systems of provisioning and governance (81 papers). The conceptualized roles are novel to the fields of urban governance and sustainability transitions as a result of our work for this chapter and a related positioning paper (Frantzeskaki et al. Reference 299Frantzeskaki, Dumitru, Anguelovski, Avelino, Bach and Best2016).

This chapter characterizes three major roles for civil society as being central to the success of moving towards sustainability transitions. First, local initiatives by civil society can pioneer and model new practices that can then be picked up by other actors (for example, policy-makers), eventually leading to incremental or radical changes in our practices and ways of organizing things. Civil society can therefore be an integral part of, and driver for, such transformations; by establishing new connections in the system, it may trigger wider change.Second, civil society can also fill the void left by a changing welfare state, thereby safeguarding and serving social needs, but doing so in new ways. Last, it can act as a hidden innovator – innovating in the shadows, disconnected from public or market actors – through initiatives that may contribute to sustainability, yet remain disconnected from wider society. There are challenges with each of these roles; we will discuss each in turn below.

14.4 Civil Society as Pioneer, Model, and Driver for Sustainability Transitions

In the last decades, we have witnessed increasing skepticism about the ability of dominant institutions (such as national governments and large businesses) to support transformations, and a growing distrust of their interest in adopting a social agenda alongside economic and political agendas (Birch and Whittam Reference Birch and Whittam2008). Given the understanding and local knowledge that civil society has gained in urban contexts through people’s direct experience of systemic problems, once initiated, civil society actors’ efforts can lead to a fast-paced realization of new ideas and new approaches for more socially, culturally, and ecologically responsible governance (Aylett Reference Aylett2010, Reference Aylett2013). Their proximity to local urban contexts, flexibility (due to operating on the fringes of complex bureaucratic settings), and elasticity allow for transformative innovation to be created and seeded by and through civil society. Civil society organizations have the knowledge and capacity to bring about projects that directly contribute to sustainability, showcasing and gathering evidence in favor of their feasibility as legitimate alternatives. Aylett (Reference Aylett2013: 862) argues that “community organizations can show the feasibility of alternative practices” and points out the direct impact civil society has in providing evidence of “what works” for sustainability.

Civil society is generally concerned with ensuring that marginalized voices are heard by decision-makers and can participate in ongoing debates on solutions and governance for sustainability transitions (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012). As such, civil society can advocate for more radical and progressive ideas, rather than “returning to old ideals” (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012). The radicalism of innovation that civil society creates is also shaped “by the attempt to sustain local levels of organization (including local culture as well as social networks) that make possible … relatively effective collective action” (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012: 12). Beyond acting as advocates, though, civil society organizations are often modeling the innovations themselves, and rapidly experimenting and adapting ideas to the local context, which, if successful, can contribute to altering ways of doing, organizing, and thinking (cultures, structure, and practices) (Boyer Reference Boyer2015; Burggraeve Reference Burggraeve2015; Bussu and Bartels Reference Bussu and Bartels2014; Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Carmin et al. Reference Carmin, Hicks and Beckmann2003; Cerar Reference Cerar2014; Christmann Reference Christmann2014; Creamer Reference 298Creamer2015; Foo et al. Reference Foo, Martin, Wool and Polsky2014; Forrest and Wiek Reference Forrest and Wiek2015; Fuchs and Hinderer Reference Fuchs and Hinderer2014; Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Eizaguirre and Pradel2015; Kothari Reference Kothari2014; Magnani and Osti Reference Magnani and Osti2016; Seyfang and Smith Reference Seyfang and Smith2007; Seyfang and Longhurst Reference Seyfang and Longhurst2013; Seyfang et al. Reference Seyfang, Hielscher, Hargreaves, Martiskainen and Smith2014; Somerville and McElwee Reference Somerville and McElwee2011; Touchton and Wampler Reference Touchton and Wampler2014; Verdini Reference Verdini2015; Zajontz and Laysens Reference Zajontz and Laysens2015; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Koroloff and Mehess2014; Warshawsky Reference Warshawsky2014; Wagenaar and Healey Reference Healey2015).

If we zoom in to the workings of sustainability transition initiatives led by civil society, we see that they can provide empirical ground or proof of concept for new market forms (such as shared economy, or economy of the common good (Felber Reference Felber2015), or for new economic structures (such as co-management, cooperatives, and alternative currencies (Orhangazi Reference Orhangazi2014; Riedy Reference Riedy2013; Walljasper 2010) by responding to a market need in a socially, culturally, and ecologically responsible and value-creating way, or in a socially structured way (Somerville and McElwee Reference Somerville and McElwee2011). As such, civil society organizations can gain both direct and indirect in market structures as well as in business organizations “through other stakeholders … via increasing consumer awareness” (Harangozo and Zilahy Reference Harangozo and Zilahy2015). An example of an initiative led by a socially driven enterprise is the Impact Hub Rotterdam, a “locally rooted, globally connected social enterprise with the ambition to connect, inspire and support professionals within and beyond the public, private and third sectors working at ‘new frontiers’ to tackle the world’s most pressing social, cultural, and, environmental challenges.” (Impact Hub Rotterdam 2015). Essentially, Impact Hub Rotterdam offers access to a working space and to a community of people working on meaningful ideas related to sustainability. Rather than competing, its members (mainly social entrepreneurs themselves) are supportive of one another, as it is in everybody’s interest that all members have maximum impact in shaping the world more sustainably (Wittmayer et al. Reference Wittmayer, Avelino and Afonso2015). In this way, the Impact Hub stretches standard ideas of how a company ought to be run, and demonstrates how companies could operate, as everybody is invited to co-shape the structures, space, and content of the Impact Hub and how a company relates to its immediate surroundings. The Impact Hub Rotterdam is connected to a global network of Impacts Hubs and, at the same time, is firmly rooted in a disadvantaged neighborhood of Rotterdam and aims to add value to these immediate surroundings by engaging in partnerships with local government, welfare organizations, and schools.

Civil society organizations not only alter ways of organizing, but also alter practices that relate to urban lifestyles. By connecting evidence on environmental degradation and impact from the global scale to local practices, civil society organizations have been able to target ways of living and consuming in cities. Being linked to a community of practice via creating stronger ties with others enforces citizens’ efforts towards leading a low-carbon lifestyle (Howell Reference Howell2013). Examples that illustrate this point emerge from civil society organizations in cities that have focused on food production, distribution, and consumption (Laestadius et al. Reference Laestadius, Neff, Barry and Frattaroli2014). Miazzo and Minkjan (Reference Miazzo and Minkjan2013) show how food can be an instrument of invention and inspiration for more sustainable lifestyle choices, as well as an entry point for holistic understandings of how lifestyles connect local to global solutions and challenges. Food-centered/food-focused civil society initiatives around the Global North partake in city making and in urban regeneration projects. As Miazzo and Minjan (Reference Miazzo and Minkjan2013: n.p.) note, “locally based food production, processing, distribution and consumption initiatives are supporting social equity and improving economic, environmental and social outcomes.” Food initiatives can be instrumental in creating urban planning synergies with local governments and in altering planning practices and approaches to include social interests, ideas, and innovations. As such, they can influence how urban regeneration may be designed and implemented, and may contribute to the creation of institutional spaces needed to revitalize local economies.

One of the main findings of the GLAMURS project has been that living more authentic lifestyles and experiencing more meaningful connections to others, especially around food production and consumption, are among the main motivations for starting and joining sustainability grassroots initiatives (Dumitru et al. Reference Dumitru, Garcia-Mira, Diaz-Ayude, Macsinga, Pandur and Craig2016). An example of one food cooperative that brings together fulfillment of such motivations, as well as contributing to altering urban planning policies in the city of Rome and enhancing their own model of land stewardship, is the Cooperativa Romana Agricoltura Giovani, or Coraggio, one of the case studies selected in GLAMURS. The cooperative joins together women and men (farmers, agronomists, chefs, architects, day workers, anthropologists, and educators) with a passion for sustainable agriculture, healthy food production, and environment and landscape preservation. It is committed to developing an urban agricultural model that is healthy, organic, and multifunctional. Overall, Coraggio’s aim is to replace degraded concrete buildings in the neighborhood with a new way of living based on environmental concerns, on respecting the dignity of labor, and on the social value and meaning of agriculture. Coraggio carried out a public debate with the Rome Municipality to obtain the concession of public lands to young farmers who can create public, multifunctional farms capable of producing food as well as services (agricultural training and experimentation, didactics, workshops, urban gardening, food services, restoration, green tourism, and outdoor sports). This transfer of lands was successful, and farmers have been managing it since 2015.

In Rotterdam, the civil society-led initiative “Uit je eigen stad” (From your own city) has emerged because of individuals desiring access to locally produced food for local consumption and the removal of middlemen in the food market. The initiative is based on a farm that also has an adjacent restaurant and market, all of which were built on vacant space in the former city harbor of Rotterdam. The civil society organization holds seminars and information days on how urban dwellers can grow their own food in the city and how to celebrate vegetarian cuisine; it has grown into a learning hub not only for urban citizens but also for smaller-scale urban farming initiatives in the city of Rotterdam. The “Uit je eigen stad” initiative contributed not only to the rethinking of vacant space in the city harbor area, but also in reimagining life in an industrial city during its slow transition to post-industrialization. The first five years of operation have positioned the founders in a diversifying and upscaling pathway; in response, the initiative has now connected and collaborates with multiple food entrepreneurs. It is prime example of successfully establishing sustainable local food production with traditional methods, with hydroponics and aquaponics that reuse waste nutrients, and with a fully operational restaurant as a circular organic food initiative.

Many cities face challenge of segregation when less affluent neighborhoods with higher proportions of low-skilled individuals who have little education and find it difficult to remain employed become socially and economically separated (Zwiers and Koster Reference Zwiers and Koster2015; van Eijk Reference Van Eijk2010). Civil society initiatives in these neighborhoods often respond to socioeconomic needs, including providing individuals with new skills to integrate them in society and the job market. Gorissen et al. (Reference Gorissen, Spira, Meyers, Velkering and Frantzeskaki2017) further illustrate that civil society initiatives contribute to establishing new local markets and repurposing existing, but unused, infrastructure for sustainable services and jobs.

An example of a civil society organization performing this function is Cultural Workplace, a foundation in Rotterdam. It originated from a one-year project by the Museum Rotterdam, which focused on creating encounters between inhabitants by renting a former shop-space in the middle of the neighborhood. Some of the interactions of residents were recorded as “modern heritage,” for example, through a radio programme. The project reached “unusual suspects” and, subsequently, a core group of those individuals stood up to continue and even broaden the purpose of the initiative, which now also includes a range of skills training workshops.

Civil society organizations also play a facilitating role between individual citizens and local and state institutions because they are trusted by individuals, employ “locally legitimate mechanisms” in mediation and communication (Stephenson 2011), and serve as a buffer of first responses from and to individuals in the event of a market failure. They thus serve as empowering contexts, enabling the seeking of new courses of action (Stephenson 2011) and working as vehicles for individual political engagement (Androff Reference Androff2012; cf. Belloni Reference Belloni2001). Civil society organizations do not operate in isolation; rather, they interact in many ways with dominant government and market logics. This raises questions concerning the distance they establish from the “centers of power” and whether they can be truly transformative. Tension occurs when civil society actors need to decide whether they strictly adhere to their core values and try to fit in while transforming dominant structures, or make compromises to make their organization adaptable to the system in which it operates (Seyfang and Smith Reference Seyfang and Smith2007: 593).

14.5 Civil Society as a Self-Organizing Actor

Civil society operates as a self-organizing actor to meet social needs that have not historically been provided by the state or the market (Androff Reference Androff2012; Barber Reference 297Barber2013; Belloni Reference Belloni2001; Bonds et al. Reference Bonds, Kenny and Wolfe2015; Brunetta and Caldarice Reference Brunetta and Caldarice2014; Caraher and Cavicchi Reference Caraher and Cavicchi2014; Célérier and Botey Reference Célérier and Botey2015; Christiansen Reference Christiansen2015; Desa and Koch Reference Desa and Koch2014; Devolder and Block Reference Devolder and Block2015; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2013; Flint Reference Flint2013; Foo et al. Reference Foo, Martin, Wool and Polsky2014; Franklin Reference Franklin2013; Hasan and Mcwilliams Reference Hasan and McWilliams2015; Kothari Reference Kothari2014; Krasny et al. Reference Krasny, Russ, Tidball and Elmqvist2014; Mehmood Reference Mehmood2016; Riedy Reference Riedy2013; Sagaris Reference Sagaris2014; Sonnino Reference Sonnino2014; Staggenborg and Ogrodnik Reference 302Staggenborg and Ogrodnik2015; Warshawsky Reference Warshawsky2015). They establish self-help dynamics (Bacq and Janssen Reference Bacq and Janssen2011; Horsford and Sampson Reference Horsford and Sampson2014) and contribute to new social orders of active citizens (Riedy Reference Riedy2013). Local civil society can counterbalance neoliberal policies and, in this way, reflect “renewed forms of democracy, solidarity and embrace of difference” (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Goodwin and Cloke2014: 2799).

When advocating or protecting common interests, issues, or values, civil society (organizations) can be aligned with or can be seen as forming a social movement. From the perspective of urban politics and urban governance, “social movements, nonviolent actions, and civic protest are not just efforts at reforming democracy, they are democracy in action” (Barber Reference 297Barber2013). Androff (Reference Androff2012: 298) addresses the democratic role of civil society for advocating social justice issues, including human rights issues that are neither influenced nor framed by political agendas in a so-called truth-seeking mission that “counters the propaganda, misconceptions, myths and untruths that are often used to create a climate of fear and intimidation and can help in reducing the stereotypes, dehumanization and discrimination that often accompany violence and injustice.” An interesting example in this regard is the participatory budgeting initiative – a participatory democracy practice – in the Indische Buurt, a neighborhood of Amsterdam. Here, the initiative of citizens aiming to understand and increase their say in municipal budgeting united with the initiative of a local government for more budget transparency, together making “for more budget transparency and accountability on the local level and strengthens participatory democracy by increasing the awareness, knowledge and influence of citizens in the neighborhood about and on the municipal budget” (Wittmayer and Rach Reference Wittmayer and Rach2016). The citizen-led initiative was based on a Brazilian practice of budget monitoring aiming to increase transparency and legitimacy of budgets based on ideas of human rights, social justice, and democracy. A fair distribution of public resources is considered key in this respect. Civil society organizations also restore the ability of local communities to connect with different urban stakeholders – not only with the local government but also with businesses – establishing multiplicity in connections and possible collaborations (Harangozo and Zilahy Reference Harangozo and Zilahy2015).

Another noteworthy example of a citizen initiative providing a space that promotes social contact and intergenerational exchange while people are having fun and acquiring new skills is the network of Repair Cafes in Schiedam, Delft, and The Hague, chosen as case studies in the GLAMURS project. Repair Cafés are free, accessible meeting places where people gather to fix broken objects by sharing knowledge of and experience with repairing things, as well as to simply have a good time with other people. One of the main aims of Repair Cafés is to reduce the amount of waste that our society produces by extending the lifetime of objects, while also teaching people that broken items can often be repaired. The Repair Cafés have also fulfilled an important social function by offering a pleasant environment in which people can meet and bolster or strengthen social contacts. Repair Cafés also provide low-cost repair options for people that cannot afford to go to regular repair venues. Martine Postma, a journalist, started the first Repair Café in Amsterdam. Based on the success of the first Repair Café, people have set up many Repair Cafés within and outside the Netherlands since 2009. In March 2016, there were over one thousand Repair Cafés in 24 different countries; their number is still growing. Postma is still actively involved in the national Repair Café Foundation and currently works on the diffusion of Repair Cafés around the world.

With the ability to articulate social needs and to experience and express the way new practices and approaches can contribute to desirable urban situations, civil society furthers the capacity to self-organize and for citizens to serve their own needs. As such, local civil society can also establish the “capacity to act,” or even counterbalance neoliberal policies and, in this way, can reflect “renewed forms of democracy, solidarity and embrace of difference” (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Goodwin and Cloke2014). An example of self-organization contributing to changes in policy is the reopening of a community center in a disadvantaged neighborhood of Rotterdam by a local action group. Beginning in 2011, the local community center had been closed due to several municipal and organizational choices, such as the decision of the local municipality not to include resources for the center in a newly issued tender for welfare work. The action group investigated possibilities for reopening the center, including intensive lobbying with different organizations, launching a petition, and acquiring and disseminating information regarding ownership structure financial obligations, and neighborhood needs. Beginning in 2012, the action group formed a foundation and unofficially reopened the center, taking on all daily tasks on a voluntary basis, notwithstanding ongoing negotiations with the municipality regarding rent and exploitation, which were not settled until 2015.

This act of self-organization did not happen in a vacuum – additional initiatives in Rotterdam were trying to achieve the same goal. Civil society organizations and their networks create polycentric arrangements via co-provision of services (Healey Reference Healey2015; Holden et al. Reference Holden, Li and Molina2015) and by supporting more economically resilient communities, or communities “consisting in economies of specialisation and flexibility” (Giammusso, Reference Giammusso1999). However, such patterns blur civil society organizations’ functions with those of a retreating welfare state, and put them at risk of becoming stretched until their innovative potential, flexibility, and elasticity disappear in the face of existing demands.

14.6 Civil Society as Hidden Innovator

Civil society acts as a hidden innovator that contributes to sustainability while often remaining disconnected from other spheres of social life (Bacq and Janssen Reference Bacq and Janssen2011; Célérier and Botey Reference Célérier and Botey2015; Desa and Koch Reference Desa and Koch2014; Doci et al. Reference Doci, Vasileiadou and Petersen2015; Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, McGuirk and Bulkeley2014; Feola and Nunes Reference Feola and Nunes2014; Forrest and Wiek Reference Forrest and Wiek2015; Fraser and Kick Reference Fraser and Kick2014; Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Eizaguirre and Pradel2015; Hasan and McWlliams Reference Hasan and McWilliams2015; Healey Reference Healey2015; Healey and Vigar Reference Healey and Vigar2015; Horsford and Sampson Reference Horsford and Sampson2014; Napawan Reference Napawan2016; Staggenborg and Ogrodnik Reference 302Staggenborg and Ogrodnik2015; Romero-Lankao Reference 301Romero-Lankao2012; Viitanen et al. Reference Viitanen, Connell and Tommis2015; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Skitmore, de Jong, Huisingh and Gray2015). In accordance with this mode of operation, civil society often innovates with the “rules in use” rather than with the “rules of the game,” meaning that they address lower-level institutions and their informal counterparts, and prioritize applying results in practice, then manifesting contrasts with existing policies and other types of formal institutions. This pattern of action is often reinforced by the public engagement and stewardship programs cities have in place for planning and by the governance of regeneration programs (Shandas and Messer Reference Shandas and Messer2008).

Researchers increasingly note the desire of civil society initiatives to remain below the radar, because, they explain, exposure comes at the expense of time and effort not spent on pursuing their founding mission. It therefore challenges the (perhaps naïve) notion that civil society wants to be discovered. The reluctance of civil society actors to become visible can be viewed in a few ways: (a) it could be the result of negative experiences, in which they have been instrumentalized by others, or, (b) it could be an expression of a desire to step away from wider society and pursue one’s own aspirations and ideas “far from the maddening crowd” (Androff Reference Androff2012; cf. Belloni Reference Belloni2001). In such cases, do alternative pathways that rely on civil society maintaining its original, alternative status would work better for citizens and cities?

A clear case of citizen initiatives striving to create an alternative to existing consumerist and accelerated lifestyles are the Romanian ecovillages studied in GLAMURS: Stanciova Ecovillage, Aurora Community, and Armonia Brassovia. These types of communities are notable among other sustainability-related lifestyle initiatives because they require their members to undergo a more radical, across-the-board transition to new lifestyle choices, consumption habits, and time-use patterns. They are usually built on the principles of permaculture, downshifting, and a sharing economy. Promoting a safe space for experimentation with a different lifestyle is present in these initiatives. This does not necessarily mean that they are invisible (as they are very open to contacts with other such initiatives and a diversity of societal actors), but it does mean they exert efforts to protect the boundaries of their experimental spaces.

If we extend our scope of analysis to the food domain, one illustrative example of a hidden pioneer enhancing a short supply chain of organic food is Zocamiñoca, a cooperative of responsible consumption in the city of A Coruña (region of Galicia, Spain) whose main objective is to facilitate access to organic products. The initiative promotes short food distribution circuits and the consumption of healthy, locally sourced food products, while also striving to assure a sustainable livelihood for local organic producers. They actively promote a change in consumption habits towards local, seasonal, and organic products. Beyond such consumption patterns, they actively encourage local participation through a structure of working groups on different sustainability themes centered on food. With more than 300 members, they have become a hub for innovative and participatory activities focused on food, and represent a place where members experience a change towards slower, sustainable lifestyles that spill over into other lifestyle domains. They promote new values of trust and strive to embed them in norms governing the relationships between producers and consumers, joined by a set of common goals and a locally embedded, common identity (Dumitru et al. Reference Dumitru, Garcia-Mira, Diaz-Ayude, Macsinga, Pandur and Craig2016).