In the modern west, reproductive fertility is a women's issue. The critical processes of conception, pregnancy and parturition all involve women far more than men. The debate about abortion is fought on (and in) the female body; fertility treatment targets the potential mother's reproductive system; surrogate motherhood invades another woman's reproductive system; and most birth control is aimed at women.

The relentless emphasis on the feminine nature of fertility has caused modern scholars and others to cast this understanding onto the study and reconstruction of the past. Female statuettes from the ancient world, naked and clothed, have been interpreted as ‘fertility figurines’, while every goddess in the ancient pantheons – be she mother or virgin or both – tends to be described as a ‘fertility goddess’. Various and sundry ‘mother goddesses’ were discovered throughout the ancient world in nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship. Today, many reconstructed neopagan religions are devoted to a monotheistic ‘Great Goddess’ who is understood to have survived the spread across Eurasia of the Indo-Europeans with their patriarchal sky god which ended the peaceful reign of the ‘Great Mother’.Footnote 1

The pendulum is now swinging the other way concerning the ‘female = fertility’ equation, especially in the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern territories once most susceptible to its lures. In 1989, Jo Ann Hackett pointed out the innately sexist implications of the theory that females are nothing but wombs.Footnote 2 There is also growing interest in the fecund male, as shown by recent publications on the masculine role in fertility in both Egyptian iconography and Sumerian literature.Footnote 3 This chapter develops, for the early literate cultures of the eastern Mediterranean, the new emphasis on the understanding of fertility as a masculine attribute, in which it is the life-giving fluids of the penis, rather than what goes on in the womb, that creates new life.

I focus on mythology – a rich surviving resource – from a swathe of territory from Egypt through the Levant and Mesopotamia into Anatolia, over a period stretching from around the end of the fourth to the early first millennium bc, although the bulk of the material comes from the second millennium. It was in their tales of creation and generation that the residents of the ancient Near East and Egypt were most explicit about their notions of gender vis-à-vis fertility, for both deities and humans. Sources pertaining to historical humans are more scattered and restricted, appearing primarily when productive processes were not functioning as they should, that is, in instances of male impotence and female infertility.Footnote 4

It is convenient to study the phenomenon of male fertility in three separate if overlapping categories. The first is cosmogony, whereby divine action brought reality itself or aspects of the natural world into existence. Here males functioned entirely alone, without any female contribution or assistance. The second is male pregnancy, where male deities were so fecund as to take on the female role of incubator, bringing forth divine progeny. The third is ‘child production’, which involved the bringing forth of either divine or human offspring, including the creation of humanity itself. In this last category a female contribution was recognized – not as creating new life, but as moulding and nourishing what a male had engendered.

Cosmogony

Male sexuality is the dominant force for fertility in ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian mythologies; it is associated with baseline creation, either of reality itself or of the natural phenomena that make up the world. Typically, this creativity is expressed in phallic and fluid-based imagery, whereby male orgasm brings forth a fluid that either engenders reality in toto or ‘fertilizes’ (that is, waters, feeds or perhaps ‘activates’) a pre-existing world. The primary example of creation emerging from ejaculation is contained in the Heliopolitan cosmogony of ancient Egypt. The Old Kingdom (c. 2700–2250 bc) Pyramid Texts relate how the primordial god Atum emerged upon the benben stone from the watery chaos called ‘Nun’. In a moment of either loneliness or arousal, he masturbated and ejaculated the deities Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture): ‘Atum evolved growing ithyphallic, in Heliopolis. He put his penis in his grasp that he might make orgasm with it, and the two siblings were born – Shu and Tefnut.’Footnote 5

This narrative is repeated in a papyrus from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1100 bc), where it is additionally noted that rather than emerging from Atum's penis, the twins were born from his mouth, possibly suggesting a kind of auto-fellatio.Footnote 6 This aspect of the story is also stressed in the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000–1650 bc), where the god Shu claims, ‘I am this soul of Shu which is in the flame of the fiery blast which Atum kindled with his own hand. He created orgasm and fluid fell from his mouth. He spat me out as Shu together with Tefnut, who came forth after me.’Footnote 7 Upon their ‘birth’, the male and female Shu and Tefnut begin the process of sexual generation, creating the deities Nut (Sky) and Geb (Earth). These grandchildren of Atum themselves engage in such intensive sexual intercourse that their father Shu must eventually separate their bodies so that their children can be born.

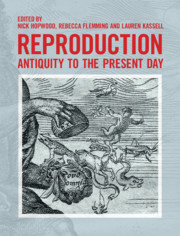

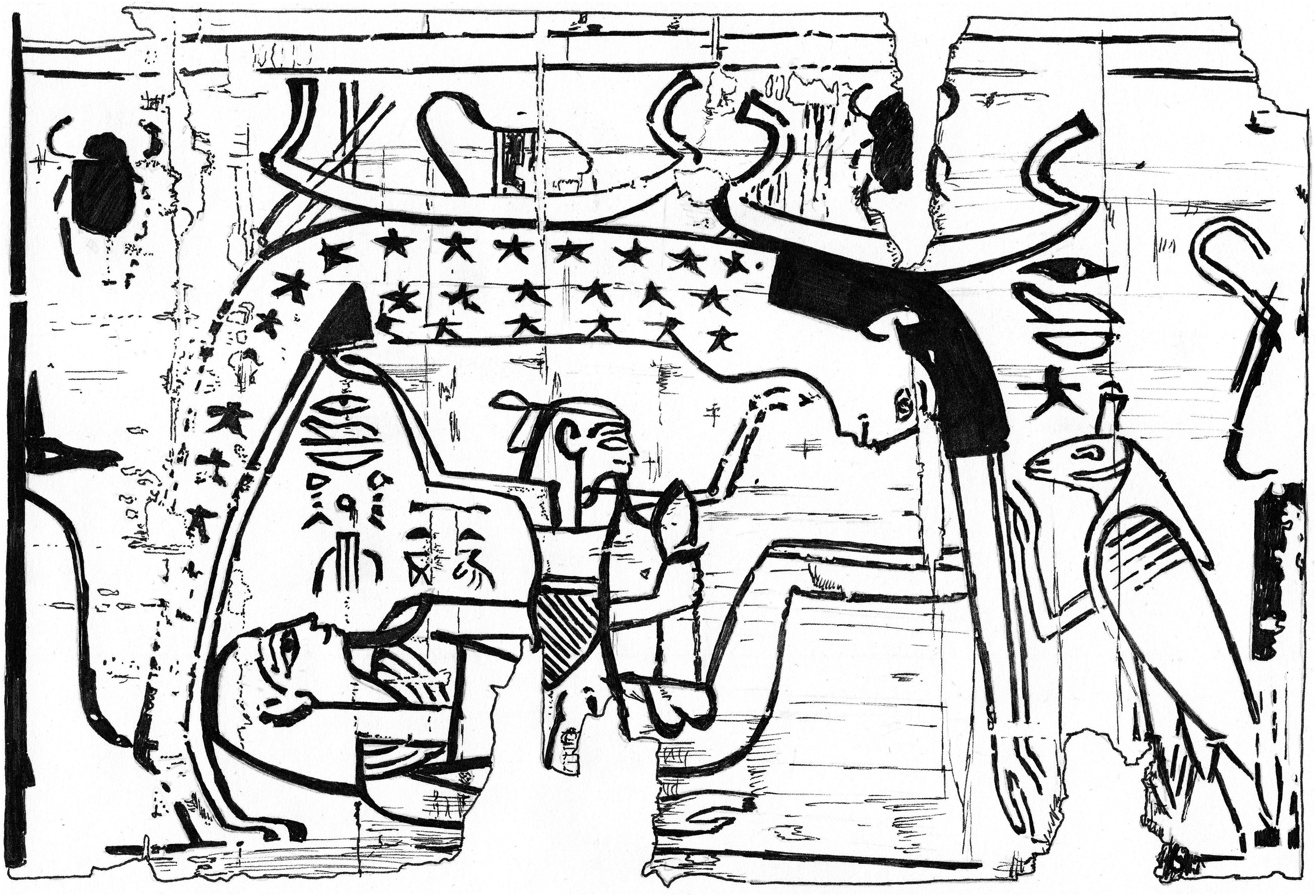

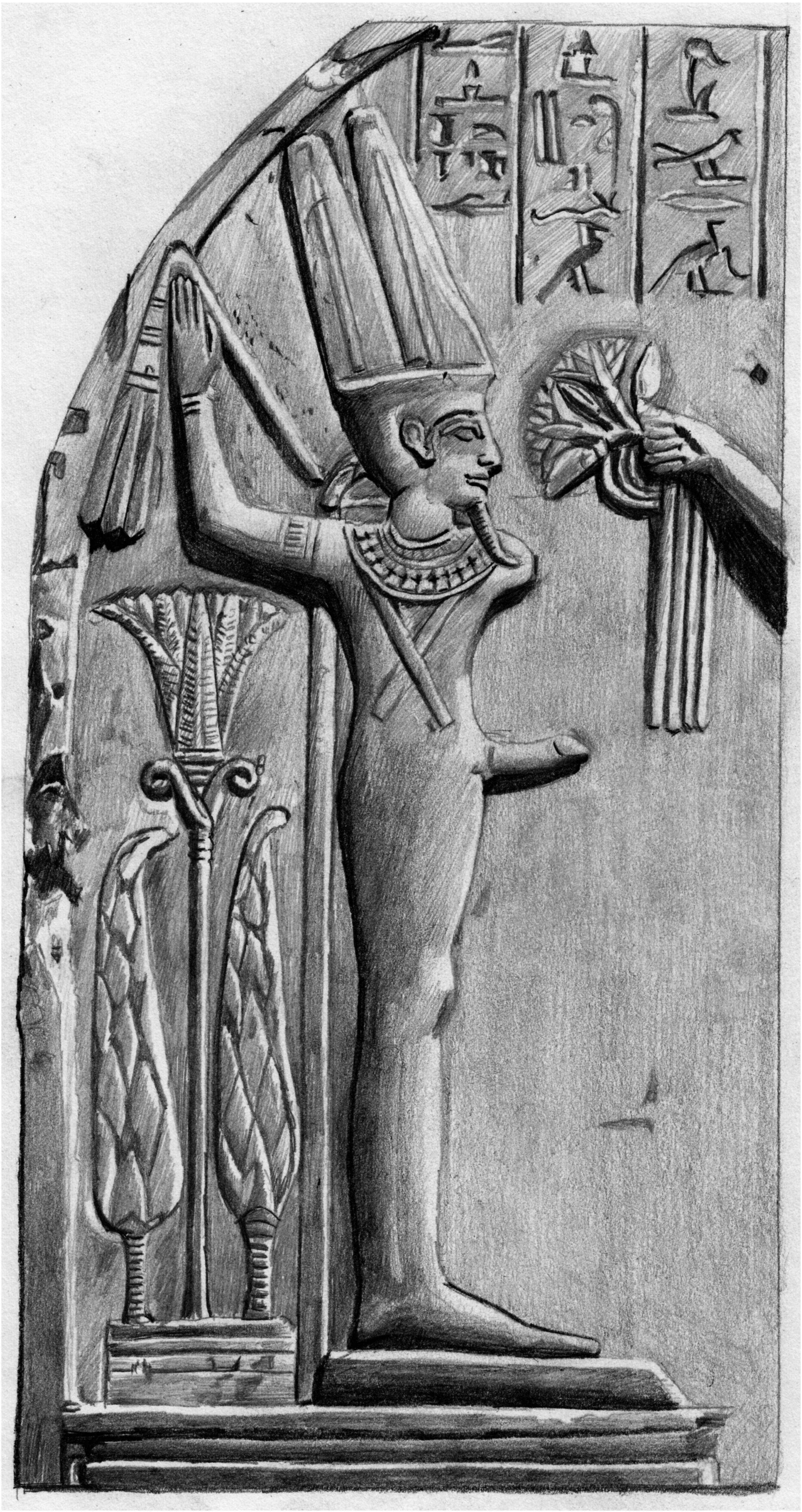

Phallic fertility is also emphasized in Egyptian iconography. Several male deities are represented as ithyphallic – with large erect phalluses – as a manifestation of their role in creation, self-regeneration and resurrection.Footnote 8 This form of presentation is evident, for instance, in a portrayal of the familial unit of Shu, Nut and Geb on a fragmentary papyrus, the Book of the Dead of Sesu, dating from the beginning of the first millennium bc (Fig. 2.1). Here Geb holds his erect phallus, in a manner reminiscent of the earlier description of Atum, while gazing upwards at his sexual partner Nut. Another common image is that of the ithyphallic god Min, whose cult originated in Coptos back in the second half of the fourth millennium bc, and developed during the Early Dynastic period (c. 3100–2700 bc). Originally portrayed alone and, once again, masturbating (Fig. 2.2), he also appeared in New Kingdom iconography gazing upon the foreign goddess Qedešet (Fig. 2.3). Qedešet bears a strong resemblance to Egyptian potency or fertility figurines, small terracotta items used to enhance physical or magical potency in Middle and New Kingdom Egypt.Footnote 9 The pairing of Min with Qedešet may thus be related to her ability to spark or intensify the god's erection.

Figure 2.1 Detail from the Book of the Dead of Sesu. This fragmentary papyrus roll, excavated from a tomb in Thebes (modern Luxor) in Egypt, contains a richly illustrated collection of spells designed to enable Sesu to navigate the afterlife. Nut (Sky) arches over Geb (Earth). Roll 20.5 cm high: British Museum, EA 9941.1.

Figure 2.2 Surviving segment of one of three colossal limestone statues of the god Min excavated from his key temple site at Coptos (modern Qift) in Egypt. Dating from around 3300 bc, the whole statue would have stood about 4 m tall. Ashmolean Museum, AN 1894.105e.

Figure 2.3 Detail from the stele of the chief craftsman Qeh. Min gazes upon Qedešet (to his left, and in the centre of the whole stele, holding flowers in her right hand). Found in Deir el-Medina, across the river from the Valley of the Kings. Figure c. 30 cm high. British Museum, EA 191.

Two other deities often depicted with erect penis were Amun and Osiris. Amun appears to have acquired his ithyphallic tendencies through syncretism with both Min and Atum. Osiris is specifically shown with erect penis when in the duat, the underworld, where his ithyphallic rendering represents his resurrection. The erect penis is a sign not only of life, but specifically of new life.Footnote 10

In Mesopotamia, the masculine nature of fertility is expressed in the exploits of some exceptionally creative deities, most notably the god of fresh water Enki. Enki was remarkable for his phallic fertility, giving rise to rivers and with them vegetal, animal and human or divine abundance. This is most explicitly presented in the Sumerian hymn, Enki and the World Order, dating to around 2000 bc.Footnote 11

After he had turned his gaze from there, after father Enki had lifted his eyes across the Euphrates, he stood up full of lust like a rampant bull, lifted his penis, ejaculated and filled the Euphrates with flowing water … By lifting his penis, he brought a bridal gift. The Tigris rejoiced in its heart like a great wild bull, when it was born … It brought water, flowing water indeed: its wine will be sweet. It brought barley, mottled barley indeed: the people will eat it. It filled the E-kur, the house of Enlil, with all sorts of things.Footnote 12

The fertility theme continues through the hymn, although with less phallic language. The god's mastery of vegetal fruitfulness is noted, for example, and that he makes young men and women sexually appealing and amorous; he can spark fertility in herd animals and field crops, and is even credited with responsibility for the birth of mortal kings.Footnote 13

Earthly fertility is also the domain of other male deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon. In the second-millennium Akkadian tale of Atrahasis, the Mesopotamian Noah, when the gods wish to destroy all humans they attempt to starve them to death by withholding the powers of the rain god Adad, once again linking notions of fluid fertility and earthly abundance with a male deity.Footnote 14 This association between masculinity and earthly bounty also appears in the high god Enlil. At the end of the Sumerian tale Enlil and Ninlil, the poet calls Enlil, ‘Lord who makes flax grow, lord who makes barley grow, you are lord of heaven, Lord Plenty, lord of the earth!’Footnote 15

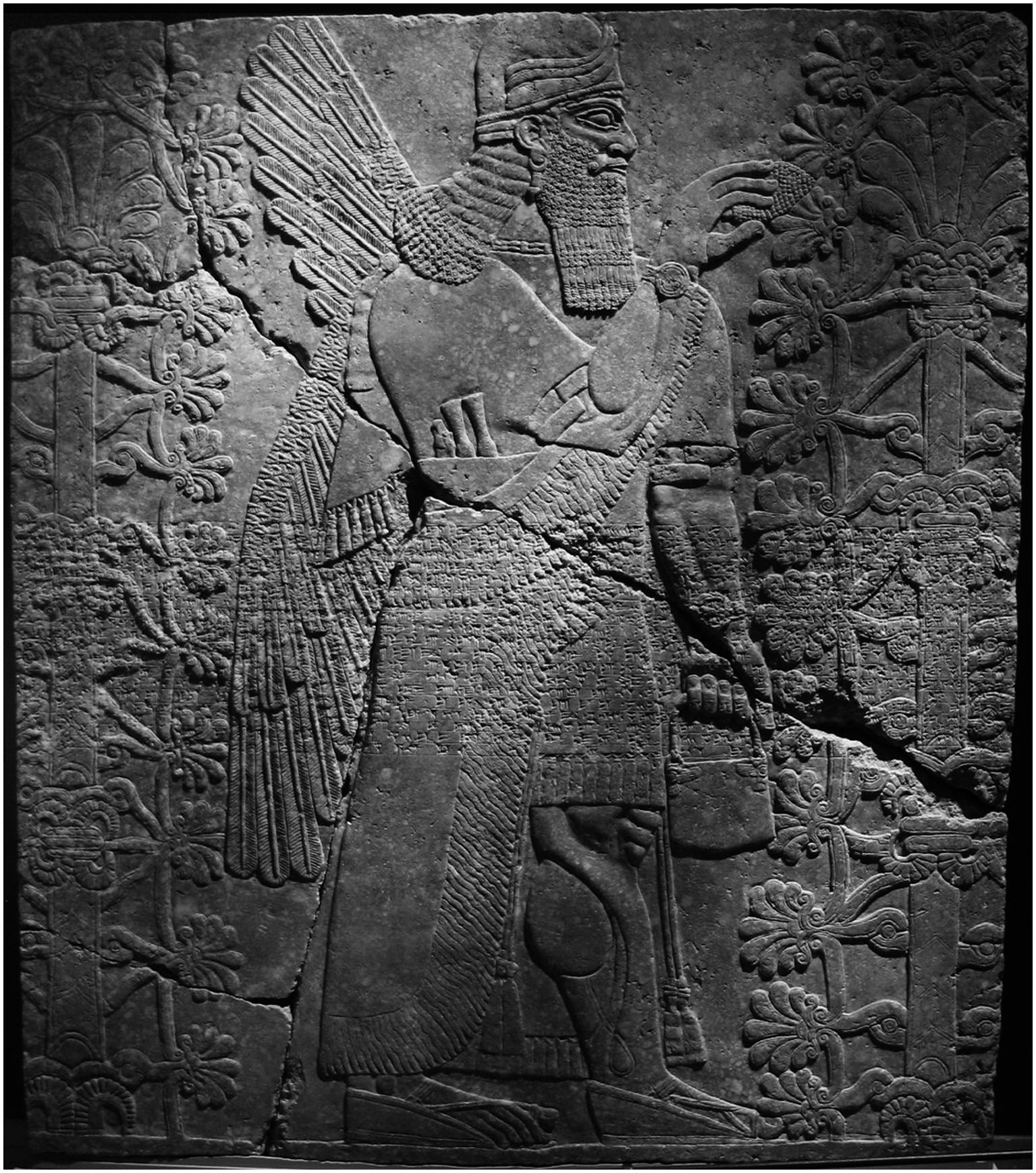

In contrast to Egyptian iconography, Mesopotamian images rarely portray the erect penis. When they do, it is in scenes of mortal sexual revelry that are conceptually divorced from notions of fertility. Instead, the Mesopotamian iconography of fertility typically involved winged male genii impregnating the ‘tree of life’, as on a wall relief from the throne room of Aššurnas.irpal II (reigned c. 883–859 bc) in Nimrud (Fig. 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Detail from a vast alabaster relief from the Assyrian palace at Nimrud, c. 883–859 bc. A winged genie holds a small pail in his left hand, and a cone in his right, through which he ‘fertilizes’ the ‘tree of life’ – a prominent symbol of prosperity and fecundity – before him. 230 × 201 cm. Brooklyn Museum, purchased with funds given by Hagop Kevorkian and the Kevorkian Foundation, 55.151.

The cosmogony presented in the Hebrew Bible's book of Genesis is distinct in so far as the deity conceptualized by the biblical redactors was transcendent, and thus, although decidedly male, could not be discussed as having a penis or creating the world in any embodied fashion. Nevertheless, elements of both creation accounts (Genesis 1 and 2, composed probably in the fifth and sixth centuries bc respectively) reflect aspects of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian narratives.Footnote 16 In addition to the male-as-creator paradigm, the first portrays a primordial state of watery chaos that is equivalent to the Egyptian Nun. Just as Atum emerged from Nun upon the benben stone, so too did Elôhîm command: ‘Let there be a dome in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’Footnote 17 In properly disembodied fashion, then, Elôhîm calls reality into being through the force of his word, rather than of his phallus. The second account more closely corresponds to the model of creation and male fertility we see in the Mesopotamian myths:

In that day the Lord God made the earth and the heavens, when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up – for the Lord God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no one to till the ground; but a stream would rise from the earth, and water the whole face of the ground …Footnote 18

Here, earth already exists, but is lifeless. The process of making a living, useful earth is tied to the presence of a stream rising, comparable to the life-giving waters ejaculated by Enki, and the eventual fall of fertile rains, comparable to those of Adad in Atrahasis. Creation is still predicated upon male fluids.

Not all of the surviving ancient Near Eastern literary corpora preserve creation accounts; there are, for instance, none amongst the extant Anatolian and Ugaritic or Canaanite texts, which also largely date to the second millennium bc. Nevertheless, even these mythic cycles present evidence of the ‘male-as-fertilizer’ paradigm, notably in tales of what happens when the relevant deity is absent, as Adad was. When the Hittite rain or storm god Telipinu disappeared:

Telipinu too went away and removed grain, animal fecundity, luxuriance, growth and abundance to the steppe, to the meadow … Therefore barley and wheat no longer ripen. Cattle, sheep and humans no longer become pregnant. And those already pregnant cannot give birth. The mountains and the trees dried up, so that the shoots do not come forth. The pastures and springs dried up, so that famine broke out in the land. Humans and gods are dying of hunger.Footnote 19

A similar situation emerges when Baal, the Ugaritic rain or storm god, is vanquished by Mot (‘Death’) in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle: the lands dry up and crops fail until his abundant return.Footnote 20

Male Pregnancy

Perhaps the ultimate representation of male fertility comes from those narratives in which male deities become pregnant, as occurs in second-millennium myths from Egypt, Mesopotamia and Anatolia. The New Kingdom Egyptian tale The Contendings of Horus and Seth relates how Seth's attempts to rape Horus are reversed by Isis, leading to Seth's impregnation:

At evening time, bed was prepared for them, and together they lay down. During the night Seth caused his phallus to become stiff and inserted it between Horus's thighs. Horus then placed his hands between his thighs and caught Seth's semen. Then Horus went to tell his mother Isis: ‘Help me, Isis, my mother, come and see what Seth has done to me.’ And he opened his hand and let her see Seth's semen. She let out a loud cry, took up her knife, and cut off his hands … Then she fetched some fragrant ointment and applied it to Horus's phallus. She caused it to become stiff and inserted it into a pot, and he caused his semen to flow down into it.Footnote 21

Isis then takes the pot of Horus's semen to the garden of Seth and, discovering from the gardener that Seth is partial to lettuce, pours the semen of Horus onto that vegetable. Seth returns to the garden, and, as usual, ate the lettuce; ‘thereupon he became pregnant with Horus's semen’. Seth becomes aware of his pregnancy in court, where he is attempting to wrest kingship from Horus in part based on his perceived ‘domination’ of the younger god. Upon the discovery of Horus's semen in his uncle, the judge Re causes the semen to emerge from Seth's head in the form of a solar disc, which Re then takes for himself.

Similarly, in the Sumerian tale Enki and Ninhursag, Enki eats a large quantity of his own semen which the mother goddess Ninhursag had placed in a variety of plants.Footnote 22 Enki becomes sick, as he has thus been impregnated with plant deities which he cannot remove from his body. The deities call for Ninhursag, who functions as a surrogate birth canal for Enki:

In the Anatolian Song of Kumarbi, the eponymous deity becomes pregnant after biting off the genitals of the sky-god Anu, whom he is attempting to overthrow.

Kumarbi bit his [Anu's] loins, and his ‘manhood’ united with Kumarbi's insides like bronze. When Kumarbi had swallowed the ‘manhood’ of Anu, he rejoiced and laughed out loud. Anu turned around and spoke to Kumarbi: ‘Are you rejoicing within yourself because you have swallowed my manhood? Stop rejoicing within yourself! I have placed inside you a burden.’Footnote 24

Indeed, several burdens: Anu has impregnated his fellow deity with a number of rivers and divinities of which he must rid himself.

In contrast to the unproblematic, even enjoyable, fertilizing activities performed by gods in the process of creation, these more generative fertility stories place their male deities in difficulty. The gods discover they lack the equipment necessary to give birth. The discomfort of the Egyptian Seth arises more from the fact that he was at least symbolically raped by Horus; but both Enki and Kumarbi realize that once pregnant they are incapable of getting their offspring out of their bodies. Kumarbi needs the support and assistance of an ultra-feminine harnau birthing-stool, while Enki must enlist the help of the mother goddess Ninhursag to remove his multiple progeny.Footnote 25

Child Production

These myths illustrate the point that, unlike cosmogonic fertility, producing children required feminine assistance. The male created new life and passed it on to the female, who incubated, moulded and nourished it within her body and through breast-feeding.Footnote 26 As a late second-millennium bc Babylonian incantation expressed it, ‘My father begot me, my mother bore me’.Footnote 27

We already encountered this uneven, heterosexual aspect of divine child production in the Heliopolitan cosmogony discussed above. After the emergence of Atum from the watery Nun and his engendering of the deities Shu and Tefnut, they and their own offspring begin the process of sexual generation that is henceforth standard. The paradigmatic union is that between Osiris and his sister and spouse Isis, as recounted in a Pyramid Text:

Your sister Isis comes to you rejoicing for love of you. You have placed her on your phallus and your seed issues into her, she being ready as Sothis, and H. ar-Sopd has come forth from you as Horus who is in Sothis. It is well with you through him in his name of ‘Spirit who is in the D- ndrw-bark’; and he protects you in his name of Horus, the son who protects his father.Footnote 28

A similar model held for human child production. Nevertheless, when humans are created by a divinity, the male potter deity Khnum is responsible, often moistening his clay with waters from the Nile, represented by the male god Hapi. Thus in the New Kingdom Tale of Two Brothers, ‘Pre-Harakhti said to Khnum: “Fashion a wife for Bata, that he not live alone!” Then Khnum made a companion for him who was more beautiful in body than any woman in the whole land, for (the fluid of) every god was in her.’Footnote 29

In Mesopotamia, the creation of humans is recorded in the Atrahasis narrative. Here, Enki summons Nintu the womb goddess to create humanity, but the goddess counters that Enki must first provide her with purified clay. In this act, Enki infuses his ‘water’ (or ‘semen’) into the matter of creation. Furthermore, the god Geštu-e is slaughtered and his blood mixed with the clay, also infusing it with life. Male liquids thus animate the inert matter. However, once the clay is properly invigorated, Nintu, either by herself or with the help of birth goddesses, moulds it into human females and males who henceforth will generate sexually amongst themselves:

The creation accounts in Genesis echo these themes. ‘Male and female he created them’, after all, with Eve's role as female assistant clearest in the following sequence, where she comes after Adam, with the pair formed to produce offspring themselves.Footnote 32 The creation of Eve as an afterthought strongly reflects the male-only monotheism of biblical theology. The Earth and everything necessary for life is created by the male god and cared for by the male human. Human child production is inherently unnecessary but invented to punish Eve. The female role in fertility is functionally accidental.

The Canaanite or Ugaritic repertoire offers a similar understanding of the hetero- sexual paradigm. In the Birth of the Gracious Gods, the focus is on the father god El, whose phallic activities give rise to a pair of voracious deities who suckle at the breasts of Athirat, the Canaanite mother goddess. In a more human venue, the Tale of Aqhat presents the story of Danel, a wise man who is bereft of heirs. The narrative begins with Danel performing a seven-day ritual to invoke the gods El and Baal so that they might provide him with a son. Baal intercedes with El on Danel's behalf, and El provides his blessing to the man, saying:

Thus we see a man calling on male deities of fertility for a son, who is given to him, incidentally through impregnating his wife.

The need for a female in the process of child production (but not creation) is clear in the ideologies of the ancient Near East. As noted in the earlier discussion, pregnant males cannot bear their offspring themselves, and mortal males must have a female to engender heirs. The idea that the female moulds new life comes across most clearly in the Sumerian tale of Enki and Ninmah. Having created humankind, these two deities get drunk and bet that no matter how bad a human the one can create, the other will find a place for it in society. Ninmah, a mother-goddess, begins, creating humans who are blind, incontinent, paralysed or stupid. In each case, Enki can find an employment for the disabled individual, even if it is merely ‘standing by the king’. But when Enki must form a human himself, he creates

Umul (= ‘My day is far off’): its head was afflicted, its place of … was afflicted, its eyes were afflicted, its neck was afflicted. It could hardly breathe, its ribs were shaky, its lungs were afflicted, its heart was afflicted, its bowels were afflicted. With its hand and its lolling head it could not put bread into its mouth; its spine and head were dislocated. The weak hips and the shaky feet could not carry (?) it on the field.Footnote 34

Enki created not an adult human, but something like a fetus, for which no occupation could be found. He could provide the start for the being, but only a female could fully form a human.

Conclusion: It's All about the Penis

The female contributions to child production notwithstanding, the credit for creativity – for new life – rested with the male. The male created new life which he then ‘gave’ to the female. The point comes through clearly in the series of recent studies of ancient Egypt and the Near East that I have synthesized and developed here, although there are also differences in emphasis between the different cultures.

Egypt provides perhaps the most completely masculine approach, in which, as Ann Macy Roth comments, ‘the creative role is attached exclusively to the male sex’.Footnote 35 This association can be seen clearly in the language. In Egyptian, the verb that we translate as ‘to conceive a child’ also means ‘to receive’ or ‘to take’; and the hieroglyphic writing system also emphasized phallic pre-eminence in fertility and generation. The image of an erect or ejaculating penis was used as a determinative not only for words such as ‘man’, ‘husband’ and ‘semen’, but also for the nouns ‘fetus’, ‘offspring’ and even ‘mother’, as well as the verbs ‘to become erect’, ‘to beget’ and ‘to impregnate’.Footnote 36

The womb does receive a little more attention in the Hebrew Bible, providing the same nourishment to the fetus as the mother earth does to vegetation that grows in it. ‘There is, however,’ as Baruch Levine says, ‘no indication … as far as we can ascertain, that the female contributes a life essence … to the embryo: the role of the female is entirely that of nurturer.’Footnote 37 The seed, the life essence, is provided by the male, and that grows inside the womb. A rather different kind of imagery emerges from the Sumerian texts of ancient Mesopotamia. Fertility, here, is water-based, and it is this fluid ‘irrigation’ which the phallus, and male ejaculation, crucially supplies.Footnote 38

In their mythologies as in their daily lives, the inhabitants of the ancient Near East and Egypt privileged the role of the male in matters of fertility and generation. The man was viewed as the creator of new life, and it is not surprising that in these consistently patriarchal and patrilineal societies children were seen as belonging to their fathers and their fathers’ families, and that men received the benefits of a prodigious brood. In the Sumerian tale of Gilgamesh and the Netherworld we read:

Amongst the Sumerian proverbs, in contrast, we note that ‘A mother who has given birth to eight sons lies down in weakness.’Footnote 40

The male right to rule and dominate was predicated at least in part on this idea of creation and ‘ownership’. As males gave rise to reality and offspring, so they had authority over that creation. In the familial context, the father ruled alongside a less authoritative (if not wholly disempowered) mother whose contributions to the continuation of the family could not ultimately be denied. In the realms of mythological, cosmogonic creativity, nothing forced the recognition of the practical feminine contribution to generation. Ideologically speaking, it was the penis that gave rise to all that was, and was good, in the ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern worlds: life came from the male.