When Swedes log in to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency’s website to request sickness or parental benefits, they have to use a so-called BankID, an electronic identity document issued by banks. How is it possible that the official proof of personal identity in basic civic issues is provided by a commercial bank? Today, seven million people, nearly the entire adult population in Sweden, have digital BankIDs. It is used not only for payments but also for online contact with public authorities such as the Tax Agency, the public healthcare system, and the municipal school system. Acting as parents or patients, why do people use identification granted in their capacity as bank consumers? The BankID was introduced in 2003 by a consortium of the largest banks, and it spread quickly. Electronic identification in Swedish society today is overwhelmingly dominated by the system offered by banks, and very few alternatives exist. It was only as late as 2011 that a governmental authority was created to supervise these systems.Footnote 1

Digital identification is a recent development, but the formalization of what could be called bank identity and the general use of official ID cards validated by banks have their roots back in the early 1960s. This was, as I will show in the article, a consequence of a new system of paying salaries and wages by direct deposit to checking accounts, introduced in the late 1950s and implemented on a large scale in the early 1960s.Footnote 2 Workers, office clerks, shop assistants, and others became account holders at commercial banks and had to get used to paying by check, and thus to consuming banking services on a daily basis. The commercial banks—until then serving mainly the business and the very rich—also started selling a wide range of products to a broad public and marketing themselves as “department stores of finances.”Footnote 3 At the same time, and as a result of this shift to retail banking, Swedish banks came to shoulder the responsibility of managing documented identities in society, which is usually associated with public authorities. Banks issued, validated, and distributed standardized ID cards to the general public.

The article describes, explains, and interprets this process in the twofold context of the history of identification, on the one hand, and the scholarship on the financialization of daily life, on the other. I ask how the validation of official individual identities came to be the specialty of banks in Swedish society, how this relates to conventional histories of identification, and what this says about a process described in recent literature as the creation of new financial subjects.Footnote 4

The article consists of three parts, followed by a conclusion. The first part deals with the above-mentioned research contexts and unpacks the relevance of my argument; the second part is concerned with the Swedish banks’ turn to a mass retailing of financial products and services; and the third and main part explores how this turn implied the banks’ engagement in the management of identification.

The study is based on archival and published sources from the banking sector, governmental and parliamentary committees, and the company AB ID-kort (ID Card Ltd.), established in 1968. While the official documents, as well as the material from banks and the Bankers’ Association helped me to track the institutional and legal changes and the creation of new financial and identificatory technologies, I also used general newspapers and house magazines from banks to access everyday practices and attitudes.

A Financial Identification Society

Commercial bodies and their role in identity management are absent from the historical literature on documented identity. Instead, this scholarship has been concerned almost exclusively with the activities of the state, as Edward Higgs points out in a recent essay.Footnote 5 The history of identity documents is traced back to colonial and wartime administrations and crime control (for example, the use of fingerprints).Footnote 6 John Torpey argues that the validation and production of legitimate identities, especially the passport (controlling people’s movement), have historically been a state monopoly.Footnote 7 In his account on the history of the passport in the United States, Robertson connects the state’s predominance in documenting and controlling individual identities to a “documentary regime of verification,” which he claims emerged between the second half of the nineteenth century and the 1930s. According to him, and others, the modern technologies of identification based on new bureaucratic logics of objectivity and on an idea of a verifiable “official” and individual identity were developed and controlled by state authorities.Footnote 8 It is only very recently, in a new digital regime, that Robertson detects “a move from the state as the primary vendor of the verification of individual identity.”Footnote 9

David Lyon, in his work on contemporary identification practices, also claims that the identity card is the manifestation of national governance by identification (and necessarily also by social sorting and exclusion). However, Lyon also points out the importance of corporate interests (for example, software companies) in the development of national ID card schemes, and introduces the idea of “card cartels” for identification systems in today’s digitalized world. He argues that while states “may still validate identity,” they are unable to act on their own but must “depend on the high-tech corporations [such as IBM] for the know-how, on softwares for the means of ‘managing’ identities and on international standards bodies […] for achieving interoperability.”Footnote 10

Edward Higgs, one of the few historians of identification interested in the role of commercial bodies, stresses the importance of historical changes in identity management, from state dominance to more dispersed and commercial identification systems in the last two decades of the twentieth century. This commercialization of identification was, however, parallel with a movement back to increased state interest in the management of identity control in the new millennium, as a part of counterterrorism and migration policies.Footnote 11 In his comprehensive history of personal identification in England, Higgs includes the emergence of tokens of identification in the new mass consumer economy. He refers here to credit and debit cards backed up by signatures, and later by PIN codes, as new “tokens of identity.” He also highlights the role of new identification technologies introduced by commercial organizations in the recent past, for example, how digitalization made detailed consumer profiling possible.Footnote 12

The role of Swedish banks in managing not only strictly commercial but also official (or at least quasi-official) identities from as far back as the 1960s is important because similar examples are lacking in the history of identification. Also, the story of twentieth-century identification practices in Sweden—by either state authorities or commercial institutions—is yet untold. There are a few studies on identity documents in older historical periods (from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries) and historical work on the politics of privacy in the data age. However, these bodies of research and the historical studies of the early and well-developed Swedish system of national registration also stress the role of state authorities, along with that of the church in the early period. Moreover, a strong “state embrace” of the individual is generally seen as typical of Swedish twentieth-century history.Footnote 13 This makes my findings even more intriguing.

So how can we understand the connection between banks and identification, and why is it important? Here, we have to consider the distinction, as also made by, for example, Lyon and Robertson, between identity and identification; or, in other words, between embedded (personal and collective) identity and documented official identity. Scholars of identification generally agree that embedded identity (related to family, community, commitment to a place) and documented identity (passport, ID cards) are intricately connected to each other; they not only depend on but also shape each other. Just like the passport has been interpreted in terms of the formation of national identities, it is possible to explore other identity devices in relation to social, cultural, or financial identities.Footnote 14

Now, personal identity literally certified by banks is easily interpreted as a powerful materialization of the birth of new financial subjects and the financialization of everyday life.Footnote 15 Although the scope of my study does not allow me to access the self-perceptions of the new ID card holders or their sense of identity, I can highlight the historical connection between the bank identity cards and the creation of a large group of new financial consumers. The sources also reveal that the new identification practices were not unproblematic, as they collided with traditional perceptions of identity and with the cultural stigma of having to prove one’s identity. I will show how the banks attempted to eliminate the shame of identification and naturalized the everyday use of identity cards with reference to money.

The concept of financial identities or financial subjects is recurrently used within social studies of finance, especially in Foucauldian interpretations of the financialized world of the recent past.Footnote 16 It highlights the fact that individuals are increasingly categorized in legal, political, and media discourses in terms of financially defined subject positions—and, as a consequence, also see themselves and act accordingly. Typical examples of such financially defined subject positions are the investor, for example, by means of the pension system or the educational system, the borrower on the housing market, or the consumer of banking products and services such as current accounts, bank cards, or insurance.

The financialization of everyday life, according to the growing literature on the concept, includes a predominance of such financial identities and their intrusion into all areas of life; in short, a new relationship between the self and finance.Footnote 17 The narrative of financialization runs parallel to and is intertwined with that of neoliberalization and globalization, and is commonly dated to the past three decades.Footnote 18

In fact, several studies of identification and surveillance refer to Nikolas Rose’s concept of “control society,” which belongs to the same theoretical tradition as the works on financialized identity positions. Drawing on Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, Rose describes a historical transition from societies of discipline—in which dominant institutions such as the school or the factory directly molded the conduct of large groups of people—to societies of control—in which the “conduct of the conduct” is done at a distance, not centralized but “dispersed and disorganized.”Footnote 19 In a society of control, Rose argues in accordance with the theory of governmentality, individuals are identified and governed by means of their different activities of working and consuming. Rose (writing in the 1990s) emphasized that commercial forces often exercise this dispersed control in contemporary society.Footnote 20

In his study of credit markets, Gilles Laferté proposes two ideal typical concepts to characterize two fundamentally different types of economic exchanges: the older face-to-face economy, built on small-scale, shared economic affiliations and social networks, and the newer economic identification economy, consisting of “mediated, remote forms of exchange.”Footnote 21 The economic identification economy relies on technologically advanced and standardized gathering of information on a very large number of individuals. Laferté’s main example is that of credit reports by credit bureaus having become a prerequisite for contemporary consumer credit.Footnote 22

To summarize, commercial engagement in identification is lacking in the historical research; and in those rare cases when commercial identification is discussed, it is explained with reference to the financialization of recent decades. Building on the insights from these scholars but also in important respects differing from their views, I argue that the history of the development of the Swedish bank identity is best described in terms a financial identification society. In this society, the banks developed a central position not only in everyday identity management for financial purposes but also in validating “official” identities in society. This happened with support from authorities (and not least with use of the national registration number), but not under state control.Footnote 23 The process started as early as the 1960s. This contradicts conventional historical studies of identification and, in fact, also the work on financialization, as it reveals that a modern concept of financial identity materialized before the era of digitalization and financialization.

The article will show how something that started as a complementary tool for administering consumer finances eventually transformed older identification practices based on class/community/status/personal acquaintance into a general and nationally valid management of formalized individual identity. Swedish banks, already in the 1960s—thus prior to the digital age—became the main identificators in society, which, of course, reinforced the connection between personal identity and finance.

A Note on Technology

Although I study how identity cards were turned into a tool—a technology—for enrolling and controlling bank customers, I only briefly touch on technology in a more literary meaning. Such a focus would need a study of its own. The processing of checks was handled first with punch-card machines and later with magnetic strips and scanners. Isotopic tracers were used in the 1970s for automatic checks of the validity of ID cards, a method that triggered anxieties about radioactivity.

Most important, of course, is computerization, which in the Swedish banking business developed rapidly during the period in question (circa 1956–1975). Sweden is characterized in research literature as an early adopter of computer technology.Footnote 24 However, the checking account system and the system of bank ID cards were at the earliest stage not driven by technological innovation. Instead, the large number of new checking accounts actualized the need for a more developed system of control and urged the introduction of technical innovations. Or, possibly, as Bátiz-Lazo and his colleagues suggest, visions about technological progress in the future, rather than existing technology, might have influenced the banks. It is important to keep in mind that it was only in the last years of the 1960s that it became technically possible to set up larger computerized databases, and it was not until the late 1970s that these became accessible online.Footnote 25 The ID card register archives were thus computerized in the late 1960s, but this register was only accessible for security checks via telephone contact with a person in charge of the terminal.Footnote 26 In historical and sociological studies of identity management in different societies, the issue of whether the ID cards are or can be connected to central records or databases is discussed as part of the overarching interpretation in terms of surveillance. While not ignoring the importance of the question, I focus here on the negotiations about and the imprinting of the everyday habit of producing an identity document.

Checking Account Salaries and the New Business of Domestic Finances, 1950s–1960s

In the late 1950s, Swedish commercial banks began offering employers the possibility for the bank to take over salary and wage payments. The companies would be spared the time-consuming and expensive work of administering cash payments, which usually also required extra staff, while the banks would increase their deposits and recruit large groups of new customers. Instead of receiving cash at the workplace, employees were paid by direct deposit into checking accounts. First, the monthly salaried employees, clerks, and office workers, and subsequently also the wage-earning workers, got their own checkbooks. A good relationship between industrial companies and commercial banks made the introduction quick. It typically happened through the mass enrollment of a company’s entire workforce at a local branch of a bank.Footnote 27

In the Swedish banking system, commercial banks traditionally served businesses rather than private individuals, except for families from society’s elite. Private savings were administered by savings banks. The state-owned Sveriges Kreditbank belonged to the former category, and the Post Office’s Savings Bank (Postsparbanken: from 1960, Postbanken) to the latter. However, these differences in business and consumer orientations were about to disappear.Footnote 28 Banking history literature explains the Swedish commercial banks’ increasing interest in the money of ordinary households in the second part of the 1950s by their desperate need of new capital due to the credit restrictions of the time.Footnote 29 Moreover, official reports pointed out the national economic advantages of channeling private money into the banking system and the supposed beneficial effect of such a reform on people’s savings behavior. State-owned enterprises were favorable to the system of checking account salaries and wages, and, in fact, one of the first employers to introduce it—in 1956—was a municipality, the City of Kalmar (by means of Handelsbanken).Footnote 30 Examples of industrial companies that adopted the new system already in the late 1950s are the IFÖ factory (ceramic and sanitary products) in Bromölla, in Southern Sweden, and Volvo, in Gothenburg (both by means of Skandinaviska Banken).Footnote 31

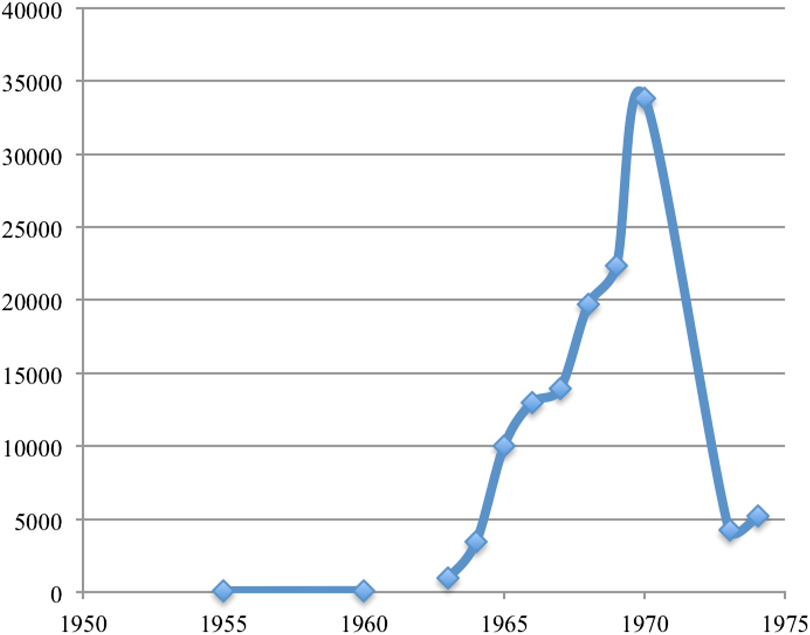

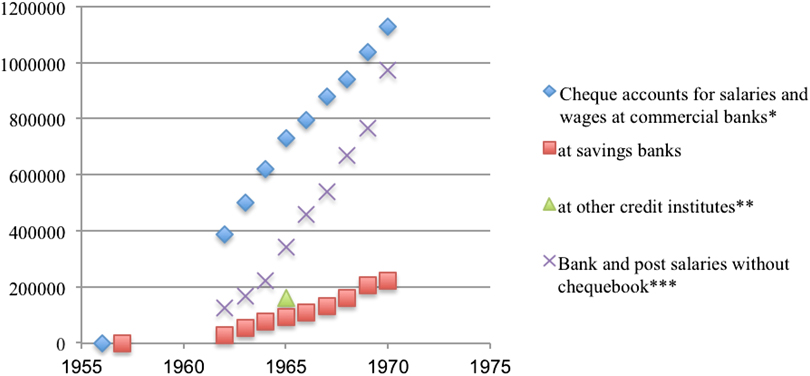

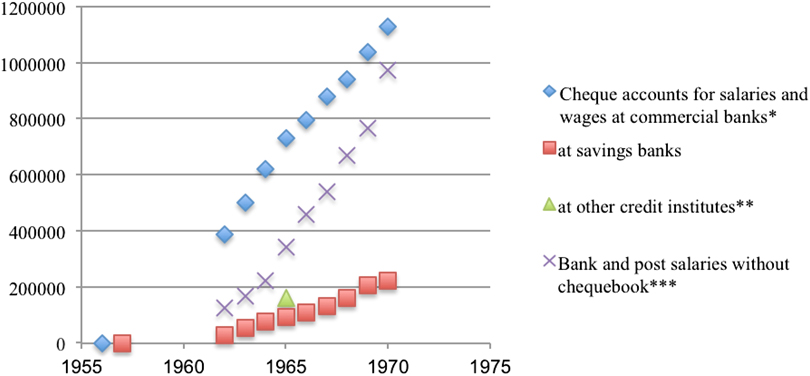

In the decade between 1957 and 1966, more than a million new checking accounts were opened, with 800,000 of them at commercial banks (Figure 1). This is a significant number, taking into account the total population of 7.6 million consisting of around 2.8 million households and a total labor force of about 3.6 million (including the agricultural sector, where bank wages were rare). In addition to checking account salaries, direct-to-account salaries and wages without checkbooks also existed, mostly administered by savings banks. The latter followed the commercial banks and started offering payroll services both with and without checking accounts. By 1970 there were more than 2.5 million accounts for wages and salaries.Footnote 32

Figure 1 Number of checking accounts for salaries and wages

* Traditional checking accounts (177,000 in 1957) not included.

** Statistics only available for 1965.

*** Includes mainly salaries administered by savings banks and the Post Office bank.

Sources: Ds Fi 1971:12, 8–11; “Postverket och checksystemet med särskilt hänsyn till checklönen” (The Post Office and the check system with particular reference to the check salary) (Report, Okt. 1966), Vol. F2b:6, archives of BF.

Savings banks had enjoyed a strong position in Sweden since the nineteenth century, and a large number of savings accounts were held by the less privileged.Footnote 33 Current accounts, however, were rare. According to a survey from 1966, only about 5 percent of new recipients of checking account salaries and wages had previously held a current account at a bank.Footnote 34 Thus, many Swedes had to learn how to handle checks and to use a bank account for purposes other than saving money.

Until the 1960s, a checking account at a commercial bank, regardless of the deposited amount, was strongly associated with the social elite. Its popularization—or “democratization,”Footnote 35 to quote the press of the time—was, therefore, a culturally controversial issue. Former Handelsbanken Director Jan Wallander stated in his memoirs that the introduction of the new system turned ingrained attitudes upside down: “Now they [the workers] were getting accounts at a commercial bank, one of the bourgeoisie’s oppressive institutions, and they were to start writing checks, something that only the upper classes did before.”Footnote 36

The checking accounts, and along with them a successive shift to monthly salaries instead of weekly wages, also challenged the everyday practices of accounting and handling money. For example, while the money in a bank account was formerly commonly “earmarked” (to use Viviana Zelizer’s well-known concept) as savings, now it had to be reconceptualized as money for spending.Footnote 37 In a similar way, the check’s earmarking as a sign of upper-class identity was affected but could not change overnight. By means of the new payroll system, wage earners automatically became consumers of financial products and services, even though they might not have seen themselves this way in the beginning.Footnote 38

The new engagement of Swedish commercial banks in recruiting customers among all social groups has been outlined in the banking history literature. The histories of the specific companies rightly point out the extent of the new policy and the fact that, with the checking account salaries, the commercial banks targeted the traditional clientele of the savings banks, thereby forcing the latter to offer similar services.Footnote 39 However, the literature on Swedish banking history does not mention the problem of identification.

The leveling of Swedish incomes contributed to the introduction of the checking account salaries. It became more lucrative for commercial banks to attract ordinary wage earners than in the past. Moreover, in the same period, a large-scale social security system was created in Sweden based on the idea of general rather than means-tested benefits.Footnote 40 Although the salaries and wages represented the most important part of households’ money, the banks also became interested in the various social payments by the Swedish welfare state and successively came to offer financial services for handling them, for example, such as a special account for child allowance.Footnote 41

Another area of financial institutions’ involvement in domestic finances was consumer credit, which became more important in Sweden starting in the late 1950s. People bought new consumer durables not only by means of hire purchase but also with savings loans from banks, or, beginning in the early 1960s, by using credit cards. A bank-owned nationwide credit card system was launched as early as 1962, the first of its kind in Europe.Footnote 42 Consumer credit was still controversial after decades of anticredit propaganda from the powerful Swedish Consumer Cooperative movement and others. Nevertheless, in the early 1960s, outstanding consumer credit debt in Sweden was among the highest in Europe (matched only by England) but much below the American numbers.Footnote 43 All this opened wide perspectives for the banks to take over the management of domestic finances and brought to the fore the need not only for credit reporting but also for identification.

Interestingly, the broad introduction of checking account salaries and wages started at least a decade earlier in Sweden than in Britain and France, despite the latter countries having more developed banking systems and more widespread usage of checks in the 1950s, at any rate among the upper and middle classes. In Britain, according to Jacqueline Botterill, bank wages for workers were delayed until the late 1970s, mainly because of the so-called Truck Acts legislation, dating back to 1831, which stated that workers had to be paid in cash (instead of, for example, orders for goods purchasable only in the employer’s shop). In 1979, 78 percent of British workers were still paid in cash.Footnote 44 Also in France, the so-called bancarisation of households was a result of legislative changes in 1966–1967, and was further accelerated by the payment of wages to current accounts and the shift from weekly to monthly payments.Footnote 45 In the French and British stories, however, there is no mention of the kind of collective affiliations with a bank that occurred in Sweden when the entire workforce of a company was given checking accounts at the same bank overnight.Footnote 46 These “forced” bank affiliations, along with the fact that this occurred when women were increasingly entering the labor market, likely contributed to the widespread Swedish habit of spouses having separate individual bank accounts. In any case, women constituted another—largely previously unbanked—group, who became checking account holders. The banking propaganda of the 1960s consciously targeted women often by associating banking with retail, consumption, and everyday household finances.Footnote 47

The Bank as a Department Store: Selling Financial Products to a Large Public

Large-scale retail banking in Sweden thus developed when the banks started offering payroll services. Bank representatives were not only hoping to increase deposits but also to sell other products and services—some of them new on the Swedish market—to a much larger public, including office clerks, shop assistants, factory workers, and their families. Internal banking propaganda, for example, house magazines, explained to bank staff: “Why, how, and what we shall sell.”Footnote 48 As mentioned above, the traditional ethos of Swedish commercial banks was to serve businesses rather than consumers. As bankers needed to acquire new skills, the banks offered their staff courses in sales techniques and customer service.Footnote 49 The internal publications reveal a new awareness of having the right “selling attitude,” which also involved the staff’s attire and general appearance (including, for example, hairstyle and make-up).Footnote 50 In 1958 the house magazine of Skandinaviska Banken published an editorial entitled “Banking Services for Sale,” written by one of the bank’s directors. He defended the new understanding of banking work as salesmanship:

Does our work really have to do with sales? Many of us might be reluctant to use the word selling when it comes to our daily activities. A bank is surely something much finer and more dignified than a grocery store or a clothes shop? But actually, there is no significant difference.Footnote 51

This was a new discourse within the banking world. In fact, the same magazine launched a debate in 1962 by asking: “Are we going too far?” The article referred to the various marketing activities and the services (including checking accounts for salaries) offered in order to attract consumers.Footnote 52

At least two of the largest commercial banks used a phrase in their advertising that likened the bank to “a department store of finances” selling merchandise such as travelers’ checks and stock certificates. A proliferation of account types (basically similar accounts differentiated mainly by name, purpose and target group) was typical of the period and fits well with the department-store metaphor. For example, the banks offered “dream holiday accounts,” “driver’s-license accounts,” and “colour-TV accounts,” all combined with some credit possibility; but there were also other special accounts, such as those for child allowance.Footnote 53

The new system of checking account salaries and wages required intensive propaganda, not only for the use of the bank and other banking services but also for the use of the checks themselves. As in in other European countries, Swedish banks started closing on Saturday to satisfy the demands of the bank employees. Saturday closing was introduced successively between 1962 and 1966—first only during in the summer and later the entire year—but it was met with harsh public discontent.Footnote 54 Critical voices in the press pointed out the absurdity of the situation. First, the banks provided everyone with unsolicited bank accounts, and then decided to stay closed on the busiest shopping day of the week.Footnote 55 In response, the banks argued in extensive information campaigns that account holders should learn to more frequently use checks to pay in the shops instead of making cash withdrawals at the bank. Used properly, banks claimed, checks were indeed a convenient means of payment for everyday consumption.Footnote 56 However, when checking account holders, in fact, listened to the bank propaganda and started using their checks, a problem of identification arose. I discuss this in the next section.

In the banks’ internal informational material on checking account salaries and wages, the bank staff was just as often described as financial educators and advisors as they were referred to as salesmen with the task of selling as many of the bank’s products as possible to new customers.Footnote 57 Jeanne Lazarus argues that French banks, after the bancarisation of the society from the late 1960s, found themselves balancing between two poles: the old image depicting the banks with traits of official institutions for public service and the new one of commercial companies offering products and services for profit.Footnote 58 There was a similar tension in Sweden but with an important difference: the image of the banks as public authorities was reinvented in a new form due to their role in the management of identification, which, in turn, resulted from their consumer orientation. In the following, I show how the banks’ turn to mass retailing implied an engagement in identity management.

Checking Accounts and Identification: Social Class and Social Control

When selling financial products and services, and especially when handling checks, bank clerks were required to confirm the identity of their customers. The changing rules and practices of the inspection of identity documents were the subject of many internal discussions and informational material, especially in the latter part of the 1960s.

In the earliest stage, when the checking accounts for salaries and wages were launched, the bankers did not seem to have reflected much on the problem of personal identification. They conceptualized their new clientele as clearly different from the old one. Elsewhere, I argue in detail that the new checking account holders were initially treated as a group, a collective of employees/workers of this or that company.Footnote 59 After all, the entire workforce at a workplace was usually enrolled overnight at the same bank, and in the beginning the company’s name could be printed on the checks or was signaled by the account number. In some cases, the banks used a person’s employment number as their checking account number.Footnote 60

Check payments, of course, entail risks of overdraft and fraud. Before the introduction of the new system, holders of traditional checking accounts were well-known clients at the bank. Now, when thousands of wage earners from the same workplace became customers at the same time, thorough scrutiny of every new account holder was not possible.Footnote 61 In a 1956 article published in Skandinaviska Banken’s house magazine, Din Bank (Your Bank), one of the bank’s managers discussed the potential risks posed by a large-scale checking account system for salaries and wages. The author claimed that the surveillance of checking account holders should not be seen as a problem at all, and that the danger of the new clientele abusing the accounts was, in fact, exaggerated. A control mechanism was “built in” to the system, he wrote. In cases of new checking customers mismanaging their accounts, their employer would be informed and would intervene. The mere knowledge of this would probably be enough to cause most people to be careful with their accounts, he reckoned.Footnote 62 Control was thus envisaged based on the customers’ identities as employees and wage earners; in a way, a class-based identification rooted in the sphere of production. In fact, as learned from the press coverage of the checking account salaries and wages in the early years, the banks actually did contact the employers in cases of overdraft or negligent handling of an account. This reveals a symptomatic attitude, which was nonetheless against the law. Therefore, the Bankinspektionen (Royal Inspectorate of Banks) had to remind the banks that the paragraph on Bank Secrecy in the Bank Law applied to the new checking customers as well as the old ones.Footnote 63

Thus, checking account wages challenged class barriers by democratizing upper-class financial practices, while at the same time the introduction of the system was rooted in a thinking permeated by traditional views of class, as new customers were initially enrolled and, in some respects, even supervised collectively in their capacity as wage earners/workers. Despite the latter, it proved difficult in the long term, as discussed below, to treat the new bank customers as a collective of employees.

From Diverse Identification Practices to Plastic Identity

In the early years of the checking account salaries and wages, a wide range of different proofs of identity was used—or, just as often, not used. The banks’ house magazines offer numerous examples of documents and objects presented to bank tellers in the late 1950s and early 1960s for the purpose of identification: social security certificates, membership cards for different professional societies and associations, licenses for firearms, certificates of change of address, tax cards, visiting or business cards, or season tickets for the railway. Even uniforms and symbolic objects, such as a doctor’s hat, a gold watch with an inscription, or a wedding ring, were used, and until the early 1960s, in fact, often accepted as identifications. Another—in retrospect dubious —method that bank clerks practiced for identification in the first years was to ask for a person’s home address and to look them up in the phonebook.Footnote 64 Official documents were rare. People seldom carried passports but often had their driver’s license with them. The latter was largely accepted—despite being easy to forge and at the time without expiration date—because it at least included a photograph.Footnote 65 Albeit on a smaller scale, the Post Office issued identity cards—in fact since 1909—“for insured letters and parcels” in accordance with international postal regulations. These were considered good solutions until the late 1960s, although not as secure as the laminated bank IDs, introduced a few years later.Footnote 66

In 1961, Remissan, the house magazine of Handelsbanken, told the story of a former employee of the bank. At the Post Office, lacking proper identification, he showed the jubilee watch with his name engraved on it, which he had received from Handelsbanken for his long and faithful service. The cashier accepted it with a smile. The magazine commented: “It is not every day that Handelsbanken distributes identity documents.”Footnote 67 However, this is exactly what the bank would do shortly thereafter. Only within a year and a half, Handelsbanken, as with other banks, started issuing and distributing their own “secure” identity cards.

In 1962 a working team within the Bankers’ Association developed a first version of a bank identity card. It was to be issued to persons “whose identity was known by the bank or could with certainty be assured.” It included a photo, signature, and expiration date (five years), and was made of forgery-proof paper with a plastic cover. It could also include a person’s national registration number or birth date, but this was not obligatory.Footnote 68

In the early 1960s, the banks motivated the need for a special bank identity card by referring to the increase in check fraud cases. Bank representatives stated that they would be “less willing” in the future to accept other proofs of identity, such as the commonly used social insurance certificate, which did not include a photo. These other types of ID documents were not forbidden, however, and it was up to the bank clerks themselves to determine whether to accept them on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 69 In the periodical Din Bank, a bank lawyer wrote that the passport was not suitable as an everyday identity document because it was relatively easy to forge, was too valuable to carry on one’s person at all times, and also had an ungainly form. There was, therefore, a great need for the new bank identity cards. “Nonetheless,” he asserted, “it would probably be more rational if a government agency provided citizens in general with identity cards.”Footnote 70

In fact, a national card had been discussed in Parliament as early as the 1920s, and in 1944 a governmental committee proposed a so-called citizen’s card along with the national registration number. The latter was introduced in 1947. However, the government seems to have been reluctant concerning the idea of a national identity card, first delaying and later definitively rejecting all plans to introduce it.Footnote 71

A Private Members’ Bill in Parliament in 1963 raised the issue that the authorities should satisfy the need for identity documents. The bill was voted down with reference to the ID cards the banks had already started to distribute, even though in its comments on the proposal the Bankers’ Association pointed out that the authorities should indeed take an active part in providing secure identity cards to the general public.Footnote 72 This reveals that the bankers felt somewhat uneasy in their new role as the issuers of identity documents, which is something they considered more a task for a public authority. At any rate, at this point they thought the distribution would be carried out successively at a slow pace, starting with the new account holders, and by providing information at the bank counter rather than through a large-scale campaign.Footnote 73

In 1965, however, when check fraud and the possible criminalization of check misuse were brought to the fore in public discussion, the requirements for check use and identification became more rigorous. For example, the youngest employees and newly hired were not immediately given checkbooks. An extensive information campaign was launched in the press to spread the stricter rules for check use. Not all identity papers with a photo would henceforward be accepted, so the banks started distributing their identity cards on a larger scale.Footnote 74 Also, the shops were no longer to be “used as banks,” meaning that they were no longer to cash checks for more than the purchase price plus rounding the sum up to the next ten, rather than a higher amount as allowed before. People were strongly advised to keep their checkbooks in safe custody, as a black market for stolen checkbooks was flourishing. The banks started organizing courses for their staff on how to confirm customers’ identity and thereby prevent fraud.Footnote 75

The check, promoted a few years earlier as an easy and convenient method of payment, was now circumscribed with complicated rules, guidelines, restrictions, and mechanisms of control.Footnote 76 One of the new bank rules in 1965 involved compulsory identity checks, which the members of the Bankers’ Association, in consultation with the National Police Board (Rikspolisstyrelsen) agreed on. Only a few kinds of “secure” identity cards were to be accepted. Also, the Swedish Trade Federation (Köpmannaförbundet) demanded a uniform means of identification with cards that were easy to verify. The federation asserted that it should be the banks’ responsibility to supply all checking account holders with such documents, considering that “it was the banks that gave rise to this evil.”Footnote 77 This was the beginning of a process that would lead to the creation of standardized identity documents for Swedish citizens.

The Shame of Identification

However, on many occasions, the real problem for bank staff and shop clerks was not the dissatisfactory means of identification in use but that they had to ask for proof of identity at all. In 1957 Din Bank quoted a customer, an accountant, who felt insulted by the polite request that he identify himself when signing a check he wanted to cash. He told the bank official that a request for identification for him meant: “You ascribe to me a criminal act. You offend me by suspecting me of being a skilled criminal.”Footnote 78 The issue was also debated in the daily papers. In 1961, Göteborgstidningen wrote:

No one, however, asks the account holders [the new checking salary account customers] what they think. They do not want the trouble and the discomfort of identification. It is unpleasant to have to show identity papers in order to dispose of their own money. “Do I look so poor or suspect that I have to show papers on who I am?” think nine out of ten of those asked to identify themselves.Footnote 79

In the literature on identity documents, some authors emphasize that an inherent characteristic of all identity documents is the suspicion of guilt.Footnote 80 This is an aspect that today, with advanced identification systems in so many everyday contexts, is not necessarily obvious but has passed, to use Mary Poovey’s words, “beneath the horizon of cultural visibility.”Footnote 81 In the past, however, the cultural problems of identification were clearly visible; it was thus shameful and could be perceived as highly offensive to be asked to identify oneself.

Although neither banking periodicals nor the general media coverage of the checking account salary system mention it, the initial negative feelings about identification might have been influenced by the fact that another place where customers could be asked to identify themselves was the Swedish alcohol monopoly’s liquor shop, Systembolaget. Between 1957 and 1964, suspicious customers could be checked against the official blacklist of peddlers and people previously convicted of drunkenness and drunk driving. Beginning in 1964, a notorious “red lamp,” signaling a random control, was installed in the liquor shops, and anyone could be asked for identification. This, a former shop manager states, was greatly disliked on both sides of the counter. However, the requirements for secure identification documents were not high in these random checks, and it appears that many kinds of papers were widely accepted.Footnote 82

The above-quoted house magazine from Skandinaviska Banken launched an internal debate in 1962 about how to ask for identification. “We can assure you that it is difficult and many will feel offended when asked for some proof of identity,” wrote the editor, introducing the subject. It was not only important to find the right tone and the right wording but also to make the public understand that it was necessary, with the standard phrase being “this is to protect your money.”Footnote 83 Also, other banks and the Swedish Bankers’ Association issued instructions and guidelines for shopkeepers, cashiers, and shop assistants about how and when to ask for the ID card.Footnote 84 Shopkeepers and sales staff often pointed out that asking for identification was indeed extremely delicate. As late as 1968 in Kontokuriren, a newsletter distributed among the checking customers of Kreditbanken, a shop assistant brought up for debate the problematic issue of asking for an ID card. She complained about how often a request for identification was met with anger because it hurt the customer’s feelings.Footnote 85 This was a recurrent topic in both banking and retail periodicals, and reveals the importance of the affective aspects in the formation of the new financial consumer. While checks could give the user a sense of pride and self-confidence in the earlier period, the demand for identification was upsetting and felt shameful. The check was a sign of class only if it was accepted without identification. Now, both old checking clients and new customers of the banks had to get used to being asked for ID documents.

The above quotes illustrate the everyday resistance and negotiations during the process, which would ultimately make it natural for everyone, in numerous situations, to produce an ID on request or even automatically. The shame initially triggered by the request for identification documents reinforces the insight that embedded identity and documented identity were—and are—deeply interrelated.

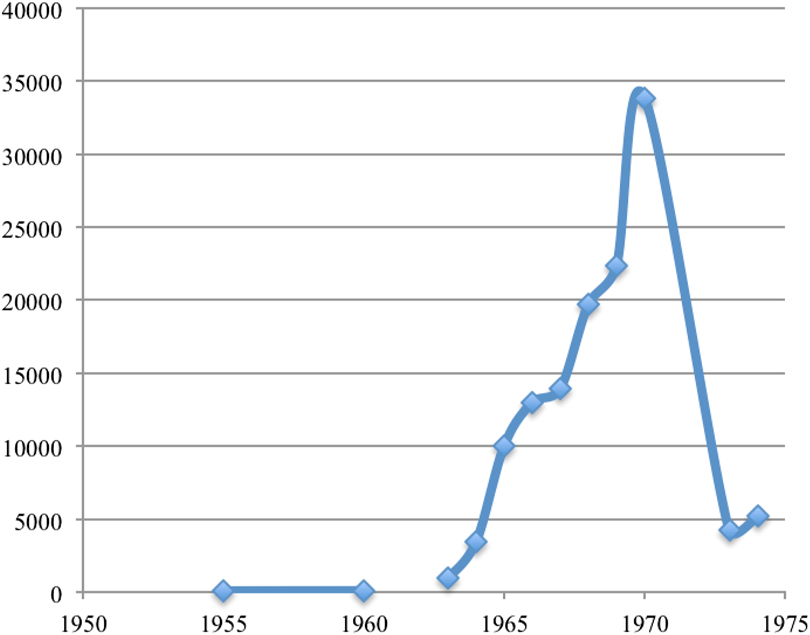

The way to handle the negative feelings in everyday commerce in the 1960s was often to give in and not confirm a check user’s identity. However, the bank guarantee for forged, altered, and noncovered checks (up to 500 SEK, about 400–500 euros in today’s monetary value) was only valid—at least for amounts above 300 SEK—if the sales clerk verified the customer’s identity and made a notification on the back of the check about the documents presented. A study conducted by the Swedish Bankers’ Association in 1970 shows that despite this, almost half of forged checks for over 300 SEK used in the retail trade lacked a note on identification.Footnote 86 The increasing rate of check fraud (Figure 2) accentuated the question of secure and easily handled identification and the destigmatization of identity checks. (The dip in the number of check fraud cases in the early 1970s illustrates not only—or not yet—the effects of the new take on identification but also a boycott on checks in retail trade, which is discussed below.)

The Bank as Identificator

As argued above, in the late 1950s, when the first checking salaries and wages were launched, the banks worked under the impression that controlling the new account holders could be handled easily through the workplace and by treating them in their capacity as employees. A few years later, they found themselves not only issuing and distributing individual identity cards but also managing efforts for a national standard for identity documents. In 1965 representatives of the banks, the General Post Office, and the National Police Board established a working group. The aim was to develop and evaluate more secure identification documents.Footnote 87 As a result of their work, in 1968 the joint stock company AB ID-kort was established for the production of identity cards. Commercial banks and savings banks owned half of the company, and the state—through the General Post Office and two industrial companies (AB Ceaverken and AB Atomenergi)—owned the other half.Footnote 88 AB Ceaverken was the only manufacturer of advanced photographic paper and X-ray film in Sweden, and the involvement of AB Atomenergi was likely motivated by its isotope technology, which was used in the early period for easy mechanical checks of cards’ validity. Thus, while the banks, along with post offices, were responsible for the validation of identity documents, and at the same time also managed, issued, and distributed the cards to the public, the state-owned companies seemingly had more influence on the technology and production process. This is at odds with the situation highlighted by David Lyon, who described the contemporary card cartels, whereby the state is responsible for the validation and issuance of ID cards but is then dependent on the technology and software offered by high-tech corporations.Footnote 89

The new company, AB ID-kort, produced three kinds of identity cards: the bank identity card, issued by banks or post offices; ID cards for private companies or public authorities for those who needed identification while on duty, such as policemen; and the new authorized driver’s license, which was introduced and produced beginning in 1973. Only these cards, besides the passport, were henceforth accepted by banks, shops, post offices, and public authorities. This essentially private solution for identity control based on the cooperation of banks and the state seems to have been internationally unique at the time.Footnote 90 Although the state was partly involved in the production of cards, it played no role in authorization and issuance. The banks served as gatekeepers and mediators of official identity.

However, the company had no formal monopoly on manufacturing identity documents. The banks’ role, as mentioned, was not only to issue and distribute the new company’s ID cards but also to authorize which identity cards could be accepted, in principle for check payments, but in practice for general use in Swedish society. The Bankers’ Association set up a Board for Identity Documents (Nämnden för legitimationshandlingar) as a consultative body in cases of inquiries for the approval of identity papers. Although the board included representatives not only from commercial banks and savings banks but also from a state authority, the Inspectorate of Banks, and from the industry, the banks’ impact was dominant.Footnote 91

This impact can be further exemplified by the fact that the bankers’ new Board for Identity Documents denied the bank approval of cards from Polaroid AB (Polaroid Ltd.), despite that these cards met the security requirements of 1972 and were in use as company identification, for example, at Volvo.Footnote 92 An ID card manufactured by another provider, AB Rollfilm (Rollfilm Ltd.), which also supplied student IDs, was approved in 1974; however, the banks declined to distribute it. Rollfilm claimed that without the banks it was practically impossible for them to market their product, and reported the case to the ombudsman for the Freedom of Trade.Footnote 93 An ID card was thus only worth manufacturing if the banks accepted it, and, moreover, if they also agreed to distribute it.

In the early 1970s, a governmental inquiry into identity control and check payments raised the question of a national supervisory authority for identity control. Despite strong support for the idea among the referral bodies, including the Bankers’ Association itself, the inquiry did not propose the creation of such an institution, and so identity control remained unregulated by law. State supervision would be exercised only indirectly through the Inspectorate of Banks’ yearly review of the banks’ operations. This meant that the banks officially retained their function as identificators.Footnote 94

The Check Boycott of 1971–1972 and the General Distribution of ID Cards

It was not until 1973 that the new bank-controlled cards, produced by AB ID-kort, were actually distributed to virtually every adult woman and man in Sweden. This wide distribution was triggered by a general boycott of checks within retail trade.

As check fraud became a growing problem in the late 1960s, the banks, at the recommendation of the National Police Board, abandoned their traditional guarantee for forged and altered checks (up to 500 SEK), starting July 1, 1971. By letting them bear the costs of fraud, the idea was to force the recipients of check payments (stores, restaurants, hotels, and so on) to enact more rigorous routines of identification, even for smaller amounts.Footnote 95 As a reaction, retailers, already discontent with all the trouble check payments entailed, announced a general boycott of checks starting from the same date. Extensive negotiations were under way for more than a year between the banks and retail trade organizations, including representatives of the Swedish Trade Federation, the Consumer’s Cooperative Union, department stores, hotels, restaurants, and gas stations. Trade unions were also involved in the discussions, representing employees with checking account salaries and wages.Footnote 96 An agreement, reached in late 1972, stated that the shops would revoke the boycott beginning in 1973 under certain conditions, such as fees on using checks for smaller amounts.Footnote 97 The most important among these conditions was that by February 1, 1973, the banks had to supply at least 90 percent of their checking account customers with “adequate” identity papers, meaning the new ID cards (or the new driver’s licenses) manufactured by AB ID-kort. All check purchases, regardless of the amount, would henceforward require an inspection of identity documents. The production and distribution of the cards manufactured by the new company were therefore speeded up significantly (Table 1).Footnote 98

Table 1 Production of cards at AB ID-kort, thousands

Source: “När AB ID-kort startade tillverkningen,” ID-nytt, no. 3–4 (1974), 4. Note: Numbers for 1974 are approximate and do not include the last four months of the year. The company also manufactured Danish ID cards from 1970, which are not included in the table. In 1975 AB ID-kort started manufacturing bankcards and credit cards as well both for the Swedish market and for export.

However, already by 1968, a governmental inquiry into possible measures to restrain the abuse of checks had been initiated. The investigator handed in his report in September 1971, a few months into the check boycott. He did not suggest any measures on the part of the government because, as he argued, these measures had already been taken or decided on by the banks: the secure ID cards, informational campaigns on keeping checkbooks safe, name or personal identity number preprinted on checks, and so on.Footnote 99 At the same time, the report of the inquiry, as well as the initial directives given by the Ministry of Finance, suggested that only a decrease in the number of checking accounts could possibly restore the general confidence in checks:

An efficient system of checking account salaries and wages depends on the account holders possessing maturity, a sense of justice and a certain sense of order. Such properties cannot be guaranteed in all employees of a company. […] If we want to restore confidence in the check as a means of payment, it appears necessary to bring down the number of checking accounts for salaries and wages.Footnote 100

Phasing out the “democratized” check system was not an option for the banks. Nevertheless, as a memo from the Bankers’ Associations suggests, they were hoping to successfully negotiate an end to the boycott when the new ID cards were ready and could be distributed to all bank customers.Footnote 101 Thus, not only did the banks become the issuers of identity documents but they also had to speed up the distribution to a very wide public. The new ID cards were different from the old bank IDs in that they included the “new” personal identity number, which was the former national registration number introduced in 1947 and supplemented in 1967 with a control digit.

After 1973, when virtually everyone was equipped with the new bank-controlled identity documents, the original reluctance to ask for and produce proof of identification seems to have disappeared. The shame and embarrassment of identification was at least no longer mentioned, either in the press or in the reports of the different investigations on the check system. Although the decade witnessed new debates on the violation of personal integrity by the new computerized systems containing personal data, the main targets of the criticism were not the banks but the governmental authorities and state surveillance.Footnote 102 Check payments were thus again possible in 1973, after the boycott; nevertheless, besides the obligatory ID inspection, as mentioned above, other restrictions applied. The initial slogans about the check as an easy-to-use, convenient substitute for cash appeared now, in hindsight, inadequate and overly optimistic.

Furthermore, the credit institutes were at this time working jointly on laying the foundations for an integrated payment system online.Footnote 103 There were already cash dispenser machines, at least in larger towns, making check payments less necessary. The first Swedish ATM opened in 1967 in Uppsala, by Upsala Sparbank, only a week after Barclays Bank installed the world’s first cash machine in Britain.Footnote 104 Cash machines offered a different solution not only to the problem of banks closing on Saturdays or to growing bank queues but also to the shamefulness of being asked for identification. It seems that identifying oneself to a machine rather than to a person did not trigger the same feeling of awkwardness; or, in any case, sales and bank personnel did not have to deal with such sentiments. Automatization thus contributed to reinforcing the naturalization of financial identifications.

Also, during the check boycott, commercial banks, including the state-owned Kreditbanken, actively encouraged their checking account customers to register for Köpkort, a credit card developed and operated by commercial banks.Footnote 105 Note, however, that ATM cards and credit cards, as two alternatives to the check, (and, in a way, also to the ID card)–– while similar in material form had different functions and were at that time loaded with opposing cultural meanings. The cash payments were deeply rooted in an ethos of thrift and were historically endorsed by the strong Swedish consumer cooperative movement. The credit card, to the contrary, objectified consumer credit and would soon come to be associated with reckless spending, consumer temptation, and also sometimes moral degeneration in public debates in the late 1970s. It is, therefore, interesting to observe how easy the step was from checking account salaries—introduced as a means of promoting savings and thrift—to credit cards.Footnote 106 It was not until 1979 that the different functions merged, when the savings banks introduced a card that could be used for cash withdrawals from ATMs as well as for payments in shops, including credit purchases. Other banks were quick to follow. ID-cards were nevertheless required for card payments in stores for a long time until online terminals were generally installed in retail.Footnote 107

More than five million identity cards (out of a total population of 8.1 million) had been produced and distributed in Sweden by the end of 1974 (see Table 1). As there was some overlap between bank ID cards and driver’s licenses, in 1974 AB ID-kort calculated that between one and two million adults in Sweden were still without proper identification. These people, housewives, the retired, and those still receiving their salaries or wages in cash, were soon to be provided with ID cards, and in most cases this also meant that they opened a current account at a bank. Finally, a nationwide advertisement campaign in 1974–1975 made manifest the connections between identity cards and money. It advertised the ID cards on large posters in the streets, in ads in the media, and on signboards displayed at the cashier’s desk, using the slogan: “It’s your money the ID Card protects!”Footnote 108

The Bank ID Card and the National ID Debate after 1975

At the initiative of the Bankers’ Association, beginning in 1981, ID cards were produced in a certified standard format according to Swedish Standards (SiS, which also fulfilled the international requirements) for plastic cards, such as credit cards.Footnote 109 At the same time, as there were no legal regulations regarding methods for identity controls or the production and issuance of such documents (other than the passport), the bank’s ID cards and the bank-approved driver’s licenses were used as official identity documents.Footnote 110 However, Swedes were not required by law—as, for example, people in some continental European states were—to carry ID documents; but, of course, this was necessary in many everyday situations, including financial transactions.

Those with no bank connection could apply for an ID card at the Post Office’s Banking Service. When post offices as such disappeared in 2001, their banking function, along with the task of issuing ID cards, was transferred to the state-owned company Svensk Kassaservice (Swedish Cashier’s Service). This latter institution was created to provide basic payment services—as an agent for Swedish banks—at places and for persons lacking other banking alternatives. It was only when Svensk Kassaservice was also abolished in 2009 that a public authority, the Swedish Tax Agency, started offering ID cards to those without access to other ID card issuers.Footnote 111

In the early 2000s, however, the international and Swedish landscape of identification documents changed. On the one hand, the state engagement in identification was reinforced. National ID cards were discussed or/and introduced in many countries after 2001, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Sweden, along with other European states, also had to adapt to EU regulations in 2005 and to handle the identification challenges of migration.Footnote 112 An interesting insight after browsing the media coverage and literature on ID cards in contemporary societies is the differences in public reception. National identity cards were criticized and contested in some countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and the United States, but could be introduced without protest in others, for example, in Belgium (compulsory national cards) and Sweden (optional national ID, but in practice it is necessary to carry either a national or bank-controlled ID card or a driver’s license). One explanation is to be found in the countries’ different histories. The introduction of a national ID card in Sweden in 2005 did not change the everyday practices of identification, while it would have very much done so in Britain, where previously identity cards were not commonly used, at least not in peacetime. The British launch of a national ID card failed, and the Identity Cards Act of 2006, introducing a national identification system, was repealed in 2010.Footnote 113

On the other hand, as mentioned initially, the increasingly important digital identification in Sweden is, once again, driven and controlled by the banks. The digital BankID is used today on an everyday basis as a quasi-official form of identification. This can be explained by a strong banking sector and the Swedish banks’ ability to cooperate, as well as, as argued in this article, by the historical connection between everyday finances and identity management in Sweden. However, more research is needed to specify the long-term effects of this historical connection.

Conclusions

The literature on identification often depicts the passport as the quintessential device for identification in bureaucratic states since the nineteenth century. However, passports have rarely been used for everyday identification. In a short book on contemporary identity services and their future, David Birch, a British specialist in electronic identification systems, distinguishes three main models for everyday official identifications in the world today. The continental model consists of “government identities [identifications] that are used by banks and businesses”; the Scandinavian model is that of banks providing proofs of identity that are used by government and businesses; and in the Atlantic model (United States, Britain) businesses and banks provide a range of different identifications, which are used by each other and by the government.Footnote 114 I have argued that such a Scandinavian model of identification, whereby the banks shoulder the responsibility of validating identities, in fact exists and, more importantly, emerged as early as the 1960s in Sweden.

Historical accounts of identification focus predominantly on state practices for production, validation, and verification of ID documents. Contrary to this scholarship, I have not only highlighted that the commercial sector in Sweden produced alternative identifications (which is, in fact, true for several other countries) but also I have pointed out that Swedish identity cards, which were validated and often also issued by the banking sector, became quasi-official identity documents. The new driver’s licenses also had this function, but these cards too were approved by banks and produced by the same partly bank-owned company as the banks’ and post offices’ ID cards. The Swedish identification system grew out of the private financial sector, which, however, collaborated with the state and used the national registration number. There is thus space for alternative histories within the “documentary regime of verification,” as described by Craig Robertson.Footnote 115

Paradoxically, the banks’ dominant role in official identification, which granted them a trait of a public authority, was a consequence of their early engagement in a mass-consumer market and their reconfiguration as “department stores of finances.” In other words, the Swedish system of everyday official identification developed from the need to identify the financial consumer. Again, this happened prior to the era commonly characterized by financialization, or described as a neoliberal control society governing and creating a range of new financial subjects. A financial identification society emerged in Sweden in the decade between the early 1960s and the early 1970s. The banks became main identificators, approving and controlling all legitimate means of identification in society but the passport. ID cards were, in principle, voluntary in Sweden, but—because of the bank transfer salaries and wages—were distributed to basically everyone and had become de facto compulsory by the early 1970s.Footnote 116

Although I did not study the long-term effects of the emergence of bank-validated identities, it is probable that it produced preconditions for later financialized identities, not least because it was also a story of normalization or naturalization of the act of identifying oneself when asked to do so in mundane daily situations. From the use of diverse and loosely defined proofs of identity referring to community, workplace, status group, and profession, a change occurred to personal, uniform, and formalized means of identification, which was materialized in the ID cards issued or approved by banks. The initial feelings of resentment and shame reveal that the transition to a naturalization of the everyday use of ID documents was a historically contingent process. The actual practice, as well as the propaganda for the destigmatization of identification, appealed to the new account holders’ financial identity by claiming: “It’s your money the ID Card protects.”Footnote 117 It was this connection, explicitly established between money and identity, which helped to turn identification into an uncontested everyday habit.