Over the past century, scholars have identified examples of liturgical chant belonging to more than one Western liturgical tradition, including Gregorian (hereafter Franco-Roman), Old Hispanic, Old Beneventan and Milanese. In a seminal essay, Kenneth Levy identified a set of offertories that circulate in the Franco-Roman, Old Hispanic and Milanese traditions, arguing that all existing versions derive from an earlier, Gallican tradition.Footnote 1 The extent of these exchanges and their implications for the early history of liturgical chant have not been fully explored. Here we expand the evidence for connections between liturgical traditions, identifying nearly two dozen Franco-Roman responsories that are shared with the Old Hispanic rite and may be of ultimate Gallican or Iberian origin. These chants can help to shed light on the nature of liturgical and musical exchange in the early Middle Ages and the histories of the rites to which they belong.

Levy's decades-long exploration of chants shared by multiple traditions has provided important conceptual models for this work. His primary goals were to identify surviving repertory from pre-Carolingian Gaul and to hypothesise about melodic transmission before the widespread use of notation. Given the broad melodic consistency in the early notated sources for the Roman Mass Proper, Levy proposed that ‘close multiples’, chants that circulate in more than one liturgical tradition, can provide the best insights into the fixity or variability of the pre-Carolingian oral tradition.Footnote 2 Perhaps most provocatively, he argued that the existing melodies allow us to recover some Gallican musical substance.Footnote 3

While our research owes much to Levy's work, we adopt a different approach and vantage point. Although some of the responsories we have identified may have originated in pre-Carolingian Gaul, discovering Gallican remnants is not our primary goal. Indeed, it is rarely possible to establish secure origins or directions of borrowing for these responsories. Instead, these shared responsories, almost all newly discovered, serve as a departure point for exploring two questions: what can these chants tell us about the nature of liturgical and musical exchange in early medieval Europe? And what are their broader implications for the history of liturgy and chant? We also hope to lay some conceptual groundwork for future research.

Identifying shared chants

To identify shared responsories, we began with texts. Using CANTUSFootnote 4 and our own compilation of Old Hispanic texts, we surveyed the entire responsory repertory. This endeavour yielded many Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman responsories based on the same passages of scripture. While these may be two versions of the same chant text, it is also possible that they are different chants, independently chosen from the same biblical source. To determine whether these were in fact the same chant texts, we relied on their ‘centonate’ nature. Many responsory texts do not come directly from scripture, but were rather compiled from different verses of a biblical book and modified in various ways. In our most convincing examples, the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman texts abbreviate or alter the biblical source in identical or very similar ways. In Induta est caro mea (Table 1), for example, both texts abbreviate the biblical source, Job 7:5–7, in exactly the same way, and both add the word ‘domine’, which is not in the biblical source. In Hic qui advenit (Table 2), both versions change the meaning of the biblical source in identical ways. At the beginning, both substitute the biblical ‘and he had a name written that no one knows’ for ‘he who comes here, no one knows his name’. Further alterations have been made at the end of the text. While the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions of Hic qui advenit have textual variants (shown in boldface), their derivation from a common source is clear. Applying this method, we identified twenty-two Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic responsories that share textual origins. These are listed in Table 3, divided into groups according to their liturgical use. Having identified these chants, we set out to position them within the history of the liturgy, consider their patterns of circulation, and assess melodic relationships between the different versions.

Table 1. Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions of Induta est caro mea

Table 2. Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions of Hic qui advenit

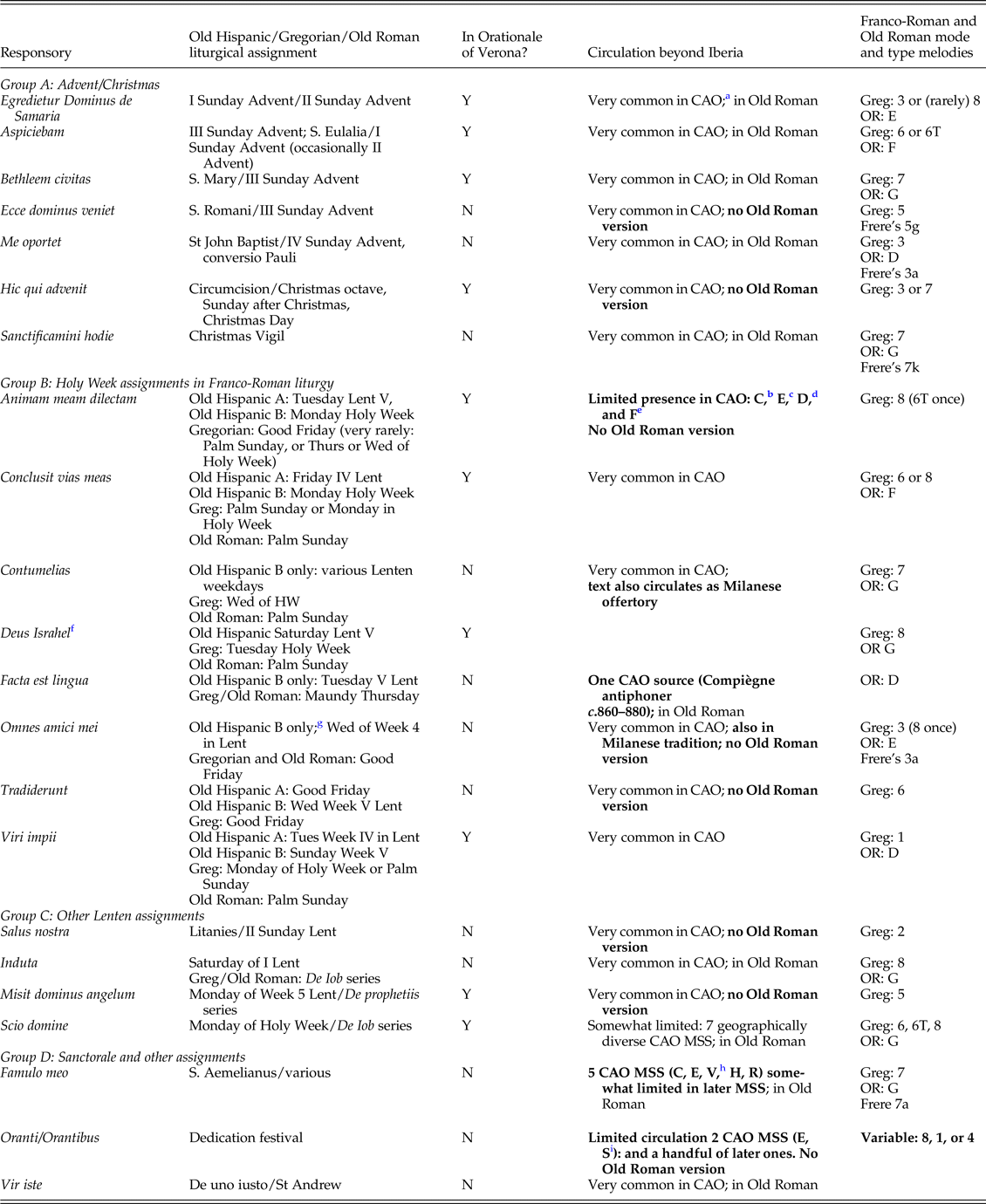

Table 3. Responsories shared by the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman traditions, grouped by liturgical assignments

a Hesbert's index of early office manuscripts, Corpus antiphonalium officii (Rome, 1963–79).

b ‘Compiègne’, Paris, BnF lat. 17436 (c.860–880).

c Ivrea, Bibl. Cap. 106 (11th cent.).

d ‘Saint-Denis’, Paris, BnF lat. 17296 (12th cent.).

e ‘Saint-Maur-les-Fosses’, Paris BnF lat. 12584.

f We have included this chant because its Holy Week assignment places it in a group of compelling instances of shared Gregorian and Old Hispanic texts. In contrast to the others, however, it is not the strongest example of a textual connection between the two traditions. The two versions are nearly identical textually, but based closely on the psalter with few modifications.

g León 8 (tradition A) has an Old Hispanic antiphon for Wednesday of Holy Week with a related but much shorter text.

h Verona, Bibl. Cap. MS XCVIII.

i ‘Silos’, London, BL add. 30850.

Liturgical groupings and manuscript circulation

Liturgical assignments and patterns of circulation offer the primary evidence for the history of these chants. Within the Roman liturgy, many of the shared responsories are associated with late sixth- and seventh-century liturgical developments, allowing us to place some exchange of repertory among these relatively late layers. As shown in Table 3, the majority of the temporale chants fall into two parts of the liturgical year: Advent (group A) and Holy Week (group B).Footnote 5 Advent is widely considered the final season added to the Roman calendar, dating, at the earliest, from the later sixth century; in Gaul, it probably emerged in the later sixth century.Footnote 6 The Roman Dedication feast (in group D), associated with the re-dedication of Pantheon in 609, is believed to be the last festival supplied with a proper set of Mass chants, although the origins of its Office chants have not been so precisely pinpointed. Holy Thursday is also a seventh-century accrual in Rome.Footnote 7 The two responsories from the De Iob series in group C (Induta and Scio) have been associated with an eighth-century revision of the night office lectionary.Footnote 8 From the Iberian perspective, two of the responsories in the sanctorale (group D) are also associated with seventh-century festivals: the Old Hispanic Marian festival (December 18), instituted in 656,Footnote 9 and St Aemilianus.Footnote 10 These seventh-century dates can serve as a terminus post quem for the exchange of repertory, though not necessarily as firm dates for the chants themselves.

To define histories and possible points of origin for these responsories, it is helpful to consider when they first appear and their patterns of circulation. Our chants were probably incorporated into the Old Hispanic repertory at different times. Just over half are in the earliest witness to the Old Hispanic repertory: the Orationale of Verona (OV), a prayer book with chant incipits written into the margins.Footnote 11 The manuscript itself dates from before 732, and its contents are believed to date from the late seventh century.Footnote 12 In its repertory and liturgical arrangement, the OV's repertory is very similar to that of the tenth-century León, Cathedral Library MS (hereafter L8).Footnote 13 Half the responsories under consideration, then, are present in this core layer of the Old Hispanic repertory. Four of the responsories that do not appear in OV (Ecce dominus, Induta, Deus Israhel and Misit dominus) are omitted as a simple result of liturgical structure: they would not have been followed by a prayer, and hence are not cued in OV. The rest of the liturgical unit to which they belong, called a missa, is present in OV, attesting to their probable use in OV's liturgical tradition.Footnote 14 The Good Friday Office (Tradiderunt) is omitted from OV, suggesting that its liturgical activities were supplied from another book. Another five responsories, however, are probable later additions to the Old Hispanic liturgy, made between the early eighth century, when OV was copied, and the tenth century, the date of L8.Footnote 15 Me oportet belongs to a missa for John the Baptist that is not in the OV but appears in L8 and is thus either a later or a regional accrual. Sanctificami hodie was part of a special terce held on the vigil of Christmas that is not in the OV. Famulo meo, Vir iste and Oranti are for probable later feasts that are not provided for in the OV: the Dedication, St Aemilian and the Common of a Just Man. These five chants allow us to place some of the liturgical exchange with the Franco-Roman liturgy between the early eighth and mid-tenth centuries. The assignment of these Old Hispanic responsories to both core and probable later liturgical layers indicates a diverse history.

Three Holy Week responsories (Facta est lingua, Contumelias and Omnes amici) appear neither in the OV nor in León 8, but may be found in a different branch of the Old Hispanic rite, commonly called Tradition B. In comparison with the early Old Hispanic manuscripts, all from the northern Christian kingdoms, Tradition B preserves a different (but overlapping) repertory of office chants, with a different (but related) melodic tradition.Footnote 16 Office chants for Tradition B, which survive only for Lent and part of Easter Week, are preserved in a single fourteenth-century manuscript from Toledo, Madrid, BN 10.110. Though there are no early witnesses to this branch of the liturgy and little is known about its history, it was probably practised in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 17

Our responsories are also diverse from the Franco-Roman perspective. As shown in Table 3, column 4, five have a limited circulation. While four of these are witnessed in the Franco-Roman liturgy by the late ninth century, appearing in the Compiègne antiphoner (Paris, BnF lat. 17436; siglum C), their circulation patterns suggest diverse histories. Animam meam dilectam (Good Friday) is found in only four of the twelve antiphoners compiled in Corpus antiphonalium officii (CAO), and its circulation in later manuscripts is also limited.Footnote 18 Famulo meo is present in four CAO manuscripts and in just fifteen Franco-Roman antiphoners indexed in CANTUS.Footnote 19 Orantibus first appears in the eleventh century, with a very limited later dissemination.Footnote 20 Finally, Facta est lingua (Holy Thursday) has perhaps the oddest circulation, appearing only in Compiègne (no later CAO or CANTUS manuscripts), in the twelfth-century Old Roman antiphoner Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, San Pietro B79, and in Old Hispanic Tradition B.

Further diversity among these responsories is evident in the absence of seven of them in the Old Roman antiphoners, copied in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These chants are distributed across the liturgical groupings. Some of them may have once circulated in Rome and later fell out of use there. For example, the presence of Hic qui advenit among responsories for the Christmas Vigil in Ordo Romanus XII indicates its presence in late eighth- or early ninth-century Rome.Footnote 21 Others may be Frankish compositions, added after the reception of Roman chant in Francia.

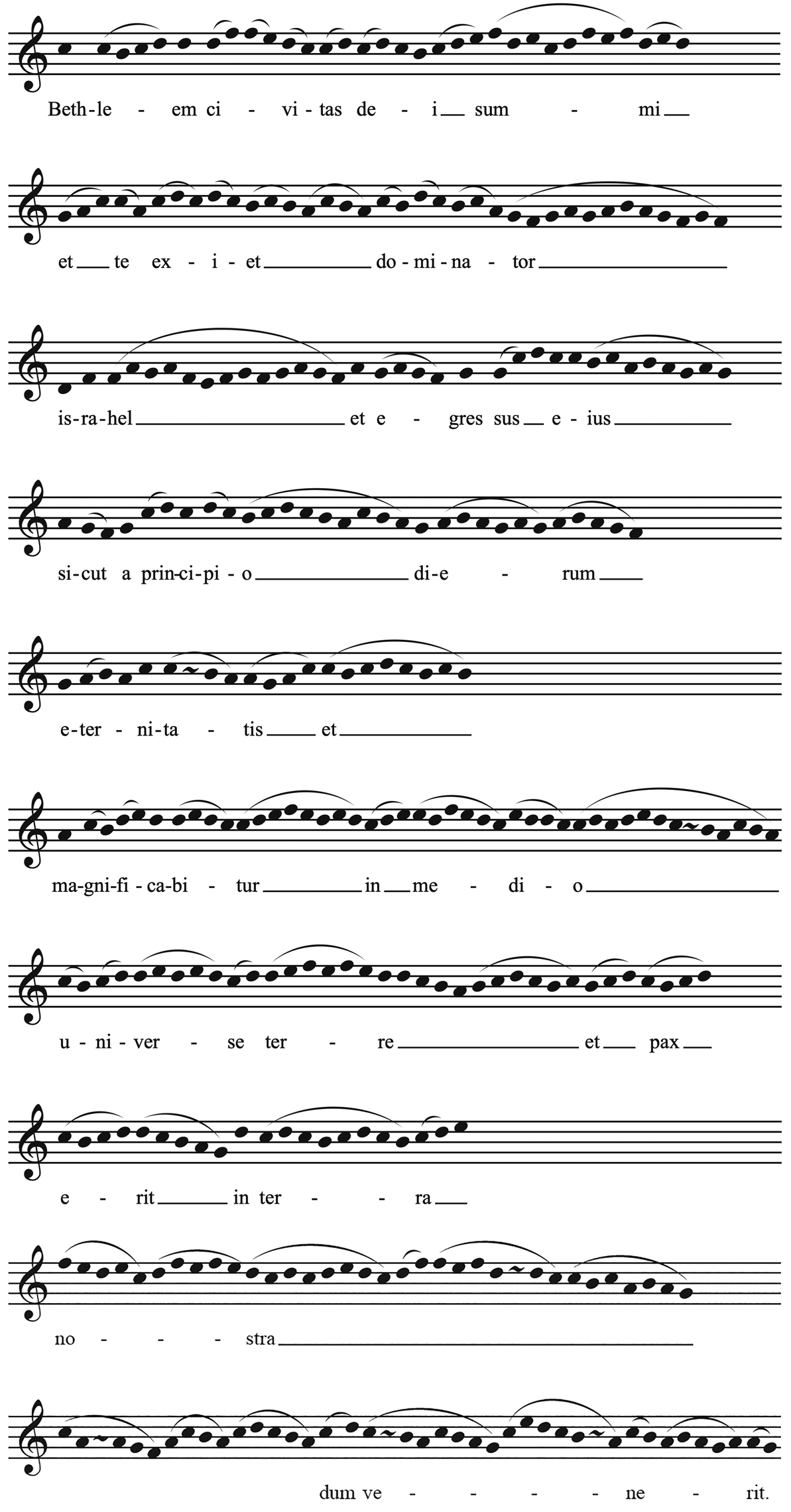

Given the use of all twenty-two responsories in the Old Hispanic liturgy, however, it is plausible that some of them were taken into the Franco-Roman liturgy from Iberia or pre-Carolingian Gaul. Theodore Karp proposed a Gallican origin for Conclusit (for Palm Sunday), citing, among other things, its use of the pes stratus and melodic connections with chants thought to be Gallican.Footnote 22 Manuel Pedro Ferreira, however, posited an Iberian origin for Conclusit. The Old Hispanic text is much longer than the Franco-Roman one, and the shorter Franco-Roman text contains a change from singular to plural that is only explicable with reference to the longer, Old Hispanic text, indicating the chronological priority of the Old Hispanic text.Footnote 23 Lengthy texts such as Conclusit are, in fact, far more typical of Old Hispanic responsories. Two other responsories under consideration, Aspiciebam and Tradiderunt, also have longer Old Hispanic texts – much longer in the case of Tradiderunt. If these responsories have Old Hispanic origins, perhaps they were shortened to conform to a more typical Franco-Roman responsory and to fit a typical periodic structure of musical phrases, discussed below.Footnote 24 In the Old Roman manuscripts, these responsories correspond to the Franco-Roman text rather than the Old Hispanic one, with the much shorter versions of Tradiderunt and Conclusit. Ferreira thus proposed that Conclusit travelled from Iberia to Gaul and then to Rome. The repertory, however, is diverse: Bethleem civitas has a longer Franco-Roman text.

Three of our responsories, Ecce dominus veniet, Egredietur and Bethleem civitas, appear in a late eighth- or ninth-century fragment, copied by Irish scribes, that reflects a blend of Gallican and Roman traits: Paris, BnF lat. 1628.Footnote 25 The presence of these responsories in this liturgical tradition does not necessarily mean that they are Gallican, since many of its chants also circulate in the Roman liturgy. Where there are substantial textual variants between the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman versions (Bethleem civitas and Egredietur), the texts of lat. 1628 match the Franco-Roman ones rather than the Old Hispanic, hinting at a closer connection with Rome. The circulation of these three responsories in lat. 1628 nonetheless attests to an early use of these responsories beyond Iberia, within a liturgical tradition that was only partly Romanised.

The diversity of these chants precludes proposing a single point of origin or direction of transmission. While an Iberian or Gallican origin seems likely for some, we know far too little about the Gallican chant repertory to posit which is more likely. Indeed, as noted, some of the responsories under consideration appear to be late adoptions into the Old Hispanic rite. Why were these chants exchanged between traditions? Ferreira suggested that Conclusit was added to the Franco-Roman liturgy because the Roman liturgy did not provide a full set of responsories for Palm Sunday.Footnote 26 Such a hypothesis is consistent with the placement of these responsories among the later liturgical layers. All these occasions were nonetheless well established in the Roman liturgy by the time of the Carolingian liturgical reforms, and thus a Roman origin cannot be categorically ruled out. In sum, the liturgical evidence does not allow us to securely posit a point of origin or a direction of borrowing for any specific chant. Given their diverse histories and circulation, these responsories likely reflect different points of contact between liturgical traditions and different directions of flow.

Melodies

Our next step was to determine whether the exchange of responsories between rites involved only texts or whether it may also have included melodies. To explore this question, we assessed the melodic relationships between different versions and then considered the degree to which these melodies are typical within each tradition. Cases of melodic borrowing examined in previous research have shown that the transfer of a melody from one tradition to another can result in melodic changes, particularly when it was disseminated before the widespread use of notation. When singers adopted a ‘foreign’ chant into their tradition, they had to negotiate differences in melodic style and formulaic content. Comparing the same chant across multiple traditions has given scholars snapshots of how these processes worked. Chants with no discernible melodic similarity between the traditions might suggest that only the texts, not the melodies, were adopted into the new tradition. In some cases, such as the Old Roman Easter Vigil tracts, imported from the Frankish north, the melodies retained the same shape that they had in the lending tradition.Footnote 27 More often, however, borrowed chants were assimilated to the style of the new tradition. For example, the Veterem hominem antiphons, adopted by Frankish cantors from Byzantium, made their way to Rome, where they were assimilated to Old Roman style.Footnote 28 Similar processes took place in exchanges between the Milanese, Old Beneventan and Franco-Roman traditions. As Levy remarked, ‘chant dialects impose their own style on whatever materials they contain’.Footnote 29

In our analyses of these melodies, we have adopted a multifaceted approach. First, we have compared the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman versions of each individual chant. Though they are not our main focus, we have also incorporated the Old Roman melodies where available. Because the Old Hispanic melodies are preserved in neumes that show contour but not specific pitches, identifying common melodic content poses special challenges. Comparative melodic analyses of chants common to the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman traditions have thus been rare, and typically limited to characterisations such as ‘broadly related’. To compare melodic contour more precisely, we gave each note a label that reflects its contour in relation to the previous note: N=unknown, H=higher, L=lower, S=same, U=same or higher, and D=same or lower. While this method has allowed us to assess contour relationships accurately, it also has limitations. The similarity between different versions of a melody may well have resided in tonal structure rather than contour. Franco-Roman and Old Roman melodies, for example, are often similar in mode, range, recitational and cadential pitches, and general contour, but differ greatly in localised, note-for-note contours. Because tonal structure is not indicated by the Old Hispanic neumes, however, the only points of comparison are melodic density (number of notes per syllable) and localised contours. Despite its limitations, this analysis has revealed some probable shared melodic content in the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions.

To contextualise these comparisons, it was essential to have a broad understanding of how Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman responsories work and to position each responsory within this framework. Each version of every chant under consideration employs formulaic material from its own tradition. Franco-Roman responsories are built, to varying degrees, from standard melodic formulas, ranging from the complete type melodies identified by Frere and Holman to individual melodies that use formulaic material mostly at cadences.Footnote 30 Their most consistent characteristic is a periodic structure: each period consists of two phrases, structured around cadences with contrasting pitches.Footnote 31 These cadential goal pitches are the genre's fundamental structural principle, determining which standard elements are used and where. In the responsories of Paris, BnF lat. 12044, Katherine Helsen identified the series of cadences that are most closely associated with each mode, forming standard tonal routes and cadential ‘roadmaps’.Footnote 32

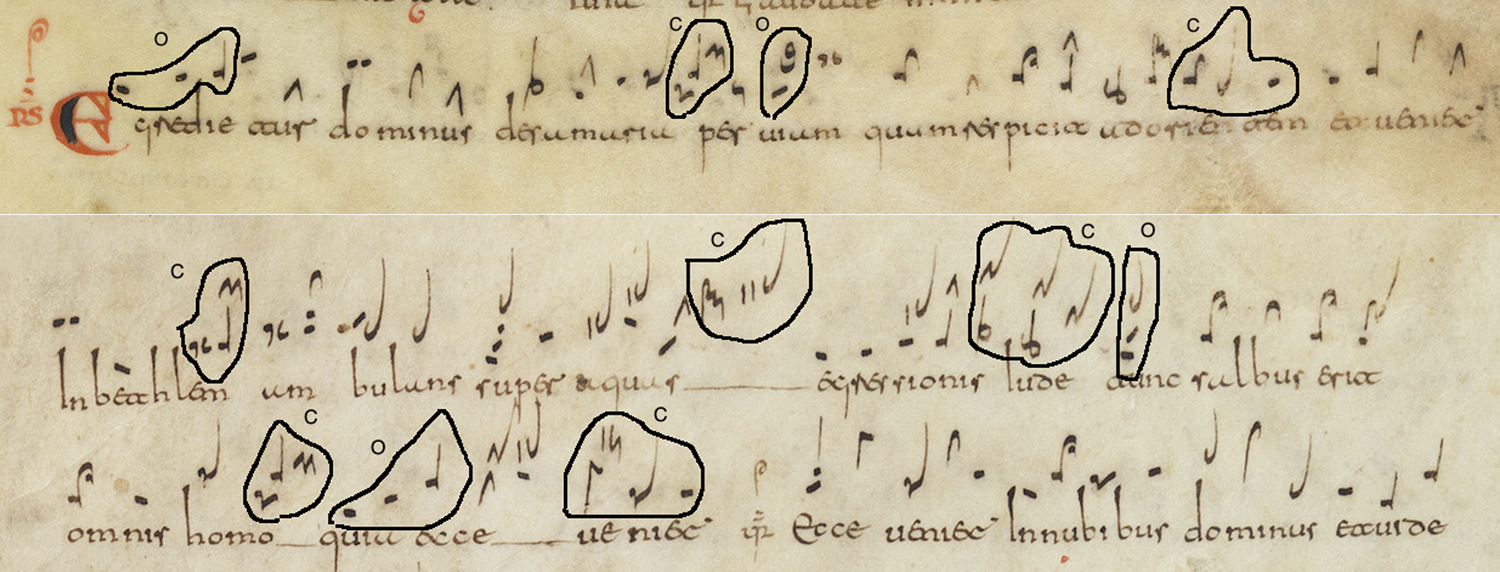

Although the Old Hispanic responsories use standard verse tones, complete melodic types are not discernible in the responsories themselves. Standard neume patterns, however, appear at verbal caesuras, allowing us to identify cadential neume combinations and contours. Often, we find sets of standard neumes at phrase openings as well. In Egredietur dominus de Samaria (Example 1), all neume combinations marked with ‘C’ occur at cadential points throughout the Old Hispanic repertory, and all neumes labelled ‘O’ are standard opening elements.Footnote 33 The Old Hispanic responsories may well have used complete standard phrases, but the sequences of unpitched neumes do not allow us to identify them.

Example 1. Egredietur dominus de Samaria, Old Hispanic (León 8, fol. 138r). (colour online)

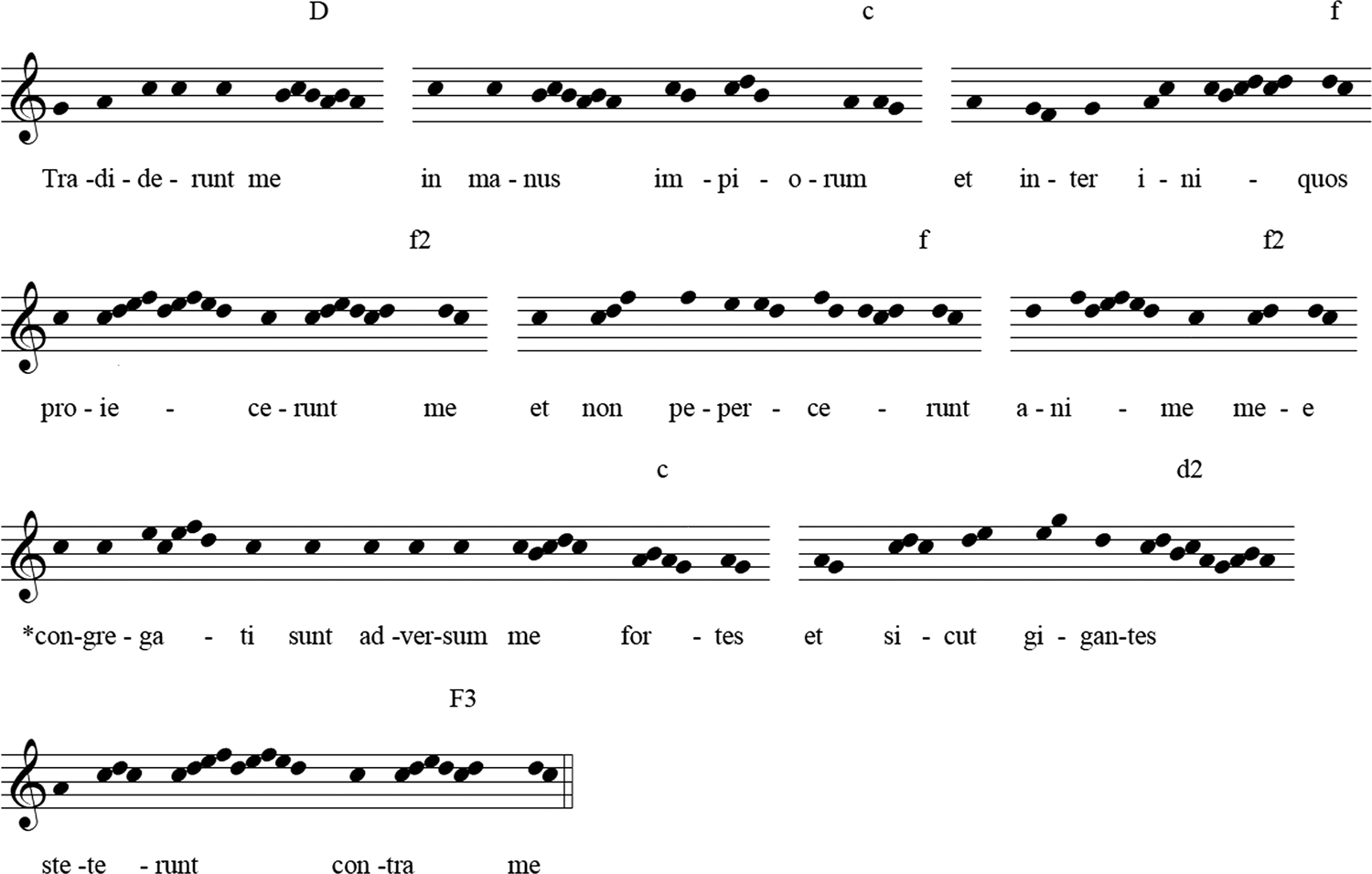

The Franco-Roman versions of our responsories show a spectrum of standard and non-standard material, typical of the genre as a whole. Five use the complete melodic types identified in previous scholarship (see Table 3, col. 5); the others mix standard and non-standard elements. Standard materials are found even in some of most plausible candidates for Iberian or Gallican origin, such as Tradiderunt (Good Friday). This responsory uses many elements commonly associated with sixth-mode responsories, as shown in Helsen's analysis of Paris, BnF lat. 12044 (Example 2). In Helsen's labelling, each formulaic element is designated by its cadential pitch and its frequency of use within that mode. For example, f2 is the second-most commonly used element ending on F in mode 6. (This particular chant is transposed to end on c in BnF lat. 12044, but the labelling remains the same.Footnote 34) These responsories, then, sound much like other Franco-Roman responsories, suggesting that they were assimilated to a familiar melodic language. This particular melody, in fact, shows no discernible melodic connection to the Old Hispanic version.

Example 2. Tradiderunt, Paris 12044 (from Helsen, Great Responsories, appendix, 156).

Although these formulas permeate all Franco-Roman responsories under consideration, some of our responsories are unusual in another respect: they depart from the typical periodic structure of the genre and the cadential ‘roadmaps’ established by Helsen. A typical responsory has three melodic periods, each consisting of two phrases. In a typical structure, the two phrases that comprise the first period end, respectively, on a pitch other than the final, followed by a period ending on the final or a common substitute pitch. The second period often has a cadence on the final, followed by one on a contrasting pitch. The final period has a cadence on a contrasting pitch, followed by one on the final.Footnote 35

Many of the Franco-Roman responsories considered here lack this periodic structure. One reason may be their atypically long texts. As Andreas Pfisterer has shown, longer responsory texts are often accommodated through added phrases within a period.Footnote 36 Some of our chants, however, altogether lack the expected patterns of contrasting cadences. Induta, for example, begins in the expected way in BnF lat. 12044's typical version, with a cadence on F, a common tonal goal for the first phrase in mode 8.Footnote 37 Every other cadence, however, is on the final G, as Helsen's analysis shows (Example 3). A contrasting pitch would be particularly expected at the penultimate cadence (‘ventus est’). Contumelias (see Example 6a) is at odds with the expected cadential sequences of mode 7, with frequent cadences on the final and without the expected contrasting cadence at phrases 1 and 4.Footnote 38 In both chants, the repeated cadences on the same pitch make a typical periodic structure difficult to discern.

Example 3. Induta, Franco-Roman, Pa 12044 (from Helsen, Great Responsories, appendix, 142).

Viri impii (Example 4) represents an intermediate position between these anomalous melodies and the most typical of the group. Helsen's prototypical cadence sequence for mode 1 is A–D–D–F–C–D.Footnote 39 Taking the major text divisions of Viri impii as a guide, we can posit eight phrases in three hypothetical periods, each ending on the final (Table 4). With this interpretation of the chant's structure, the first and last periods have three phrases rather than the standard two, and several unusual characteristics emerge. The first phrase of the second period ends on a, rather than the typical final; a occurs in this position fewer than ten times among 212 first-mode responsories in BnF lat. 12044.Footnote 40 The close of the second period on the final, rather than on a contrasting pitch, characterises only thirty first-mode responsories; a penultimate cadence on a is found in only twenty-three.Footnote 41 Thus, while Viri impii may be fitted within an expected periodic framework more easily than Induta or Contumelias, it does not conform to the structural expectations of the genre in mode 1. Similar traits are discernible in several other responsories of our group.

Example 4. Viri impii, Franco-Roman, Pa 12044 (from Helsen, Great Responsories, appendix, 147).

Table 4. Hypothetical period structure in Viri impii

It is difficult to know what to make of these anomalies, which cannot be fully explained by the exceptionally long texts. Since these responsories circulate in the Old Hispanic liturgy, it is tempting to see their atypical traits as possible markers of ‘foreign’ origin. Induta and Viri impii, however, show no correspondence to the Old Hispanic versions. Even in Contumelias (discussed later), there are too few contour similarities to hypothesise that the Franco-Roman tonal structure reflects that of a putative Iberian or Gallican ancestor. It is possible, however, that the unusual traits of the Franco-Roman versions arose through attempts to absorb a stylistically unfamiliar chant into the repertory. A few of the other Franco-Roman responsories in the group have conflicting modal assignments (see Table 3, col. 5), perhaps further attesting to such difficulty. Conclusit presents extensive tonal difficulties, as Karp and Ferreira have shown.Footnote 42

Relationships between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic melodies

Because these responsories use melodic formulas, we would expect the Old Hispanic, Franco-Roman and Old Roman melodies to differ according to the stylistic tendencies of each tradition. In every responsory under consideration, such differences between the versions are pervasive. Points of melodic similarity are nonetheless discernible in just over half of the melodies (Table 5). For the ten responsories in column 1, the divergences between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions are often substantial enough to suggest different origins for the two melodies. The remaining chants have passages of similarity between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic melodies, either in melodic density only (col. 2), or contour and melodic density (col. 3).

Table 5. Types of relationship between Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman responsories

How we understand these similarities depends in part on how each version relates to the characteristic formulaicism within its tradition. When the similar passages coincide with non-formulaic parts of the melody, they may indicate traces of a common melodic ancestor. When they coincide with material that is formulaic in one or both versions, this, too, could point to a shared origin, but may also highlight general commonalities between Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman chant. In fact, the use of identical (or nearly identical) texts in these responsories uniquely positions us to identify melodic vocabulary and text-setting strategies common to more than one chant tradition.

In the following case studies, we consider the responsories in Table 5, columns 2 and 3, in a kind of thought experiment. Our goal is not to ‘recover’ a shared ancestor and neither can we securely establish the chronological priority of one version over another in most cases. Rather, we hope to open new methodological possibilities for exploring what these cognate chants can tell us about the similarities and differences between the two chant traditions and the transformations that took place in the course of borrowing. Each of these responsories is different in nuanced ways, opening up a different set of possibilities. For most of the Old Hispanic melodies, L8 serves as our primary source. Copied in the tenth century, it is the earliest complete manuscript of Old Hispanic chant and the only one to preserve most of our chants. As noted, the thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Toledan manuscript Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional 10.110 represents a separate branch of the rite (Tradition B) and presents very different versions of the melodies. Since it is the only source for a handful of our chants, we consider it as needed. For the Franco-Roman tradition, we have selected a pitched manuscript to provide the most complete information about contour. Additional manuscripts, examples and complete chants are provided in an online supplement.Footnote 43 Although our primary questions centre on the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic traditions, we incorporate the Old Roman versions in a few cases to illustrate commonalities across all three traditions.

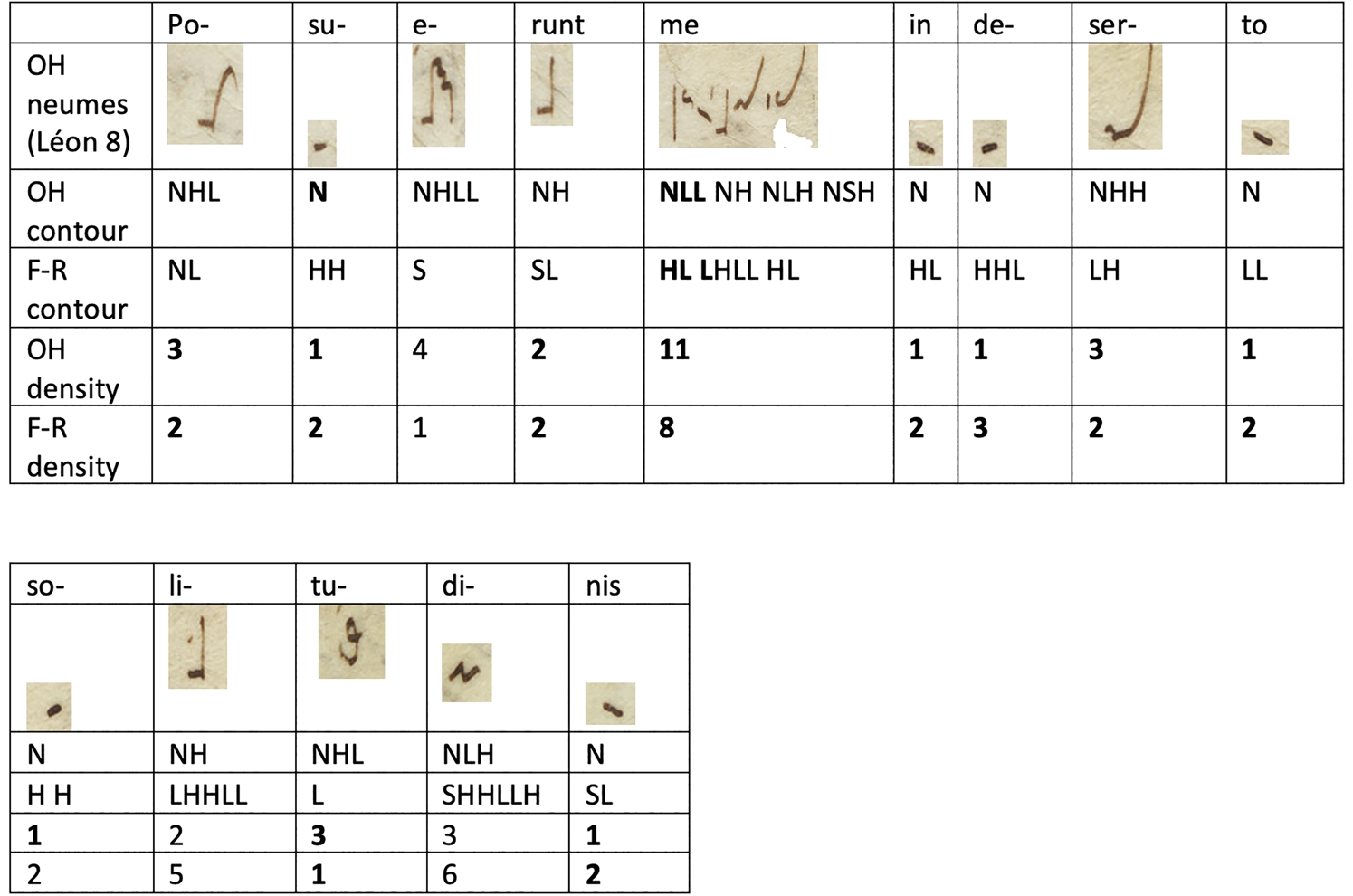

In our first set of examples, similarities of contour and density are manifest primarily in formulaic material, allowing us to identify formulaic content shared across traditions. Animam meam dilectam has both divergences and commonalities of formulaic content. The Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions share the very broad tendencies in text pacing that characterise responsories in both traditions: most syllables have between one and five notes at the opening and middle of a phrase. At the ends of phrases, the pacing often (but not always) slows. The distribution of standard cadential material over the last one to five syllables varies according to the specific cadential formula. As a result, the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic melodies often differ in melismatic density at these points. In Animam meam dilectam, this can be illustrated at ‘posuerunt me in deserto solitudinis’ (Examples 5a and 5b). In addition to the contour, indicated with NSHLUD, we have shown the number of notes per syllable on each word in the bottom two rows. In most of the passage, the two versions are similar in density (at the points indicated by boldface). Each version divides this sentence into two short phrases, with a cadential melisma on ‘me’. At the end of the complete sentence, however, the two versions use different cadence types, resulting in a different density on ‘solitudinis’. In the Old Hispanic version, the neume on the penultimate syllable, followed by a single, lower-placed note, functions in the repertory as a short, non-melismatic cadence.Footnote 44 The Franco-Roman cadence, also standard, has far more notes per syllable. Given this formulaic content, each version would have sounded typical to practitioners within each tradition. Despite the use of different cadence types, however, both settings of this text place a cadential melisma on ‘me’, when the whole sentence could have been treated as one phrase. This form of rhetorical emphasis on ‘me’ permeates the Old Hispanic Lenten chants across genres.Footnote 45 Was this choice made independently in each tradition, or does it suggest that they are distant descendants of a common ancestor?

Example 5a. Animam meam dilectam, passage 1, ‘posuerunt me in deserto solitudinis’, Franco-Roman (Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, C5, fol. 141v).

Example 5b. Animam meam dilectam, passage 1, ‘posuerunt me in deserto solitudinis’, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 146r). (colour online)

We can think through these two possibilities as we consider other parts of the chant. The complete chant (not shown in the example) divides into ten verbal clauses that are marked with cadences in both traditions.Footnote 46 Most of these phrases, like the passage just examined, have different cadence types in the two versions, with resulting differences in melodic density and contour. When the two versions do use similar cadences at the end of the chant, however, they show similarities both in density and in contour. This can be illustrated in the passage shown in Examples 5c and 5d, where the contour and density parallels are highlighted in boldface. The cadences on ‘cognosceret/agnoceret’ and ‘bene’ are both very standard within each tradition and have similarities in contour. The Franco-Roman version is also typical tonally on ‘agnosceret’, since D is the most common goal for a penultimate cadence in eighth-mode responsories.Footnote 47 It is true that the exact contours of these cadences can vary among manuscripts within each tradition: standard cadences in the Franco-Roman responsories can be replaced with others, and in the Old Hispanic melodies, cadential contours can vary according to regional preferences.Footnote 48 What this example shows is that similar contours fall within the range of cadential possibilities in both Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman chant. Animam meam's absence in the Old Roman tradition and its limited circulation in early Franco-Roman manuscripts renders a Roman origin unlikely. It is more probable that the Frankish liturgists borrowed this chant either from Iberia or Gaul. The points of commonality between the two versions, then, may reflect vestiges of a common melodic ancestor that underwent substantial changes in a process of stylistic assimilation.Footnote 49

Example 5c. Animam meam dilectam, passage 2, end of the chant, Franco-Roman (Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, C5, fol. 141v).

Example 5d. Animam meam dilectam, passage 2, end of the chant, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 146r). (colour online)

This commonality of formulaic content may be observed among many of the chants in Table 5, cols. 2 and 3. These passages confirm that the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic melodies shared aspects of melodic vocabulary and that some melodies may descend from a common ancestor. Contumelias exhibits these characteristics most consistently. The Old Hispanic version is preserved only in the Tradition B manuscript Madrid 10.110. Although we know far less about the typical cadential neume patterns in Tradition B,Footnote 50 nearly all of the major text divisions have neume combinations that are plausibly cadential, based on tradition A.Footnote 51 The Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions have a similar melodic density in many passages, and in some cases, these are matched by common cadential contours. Each of these passages, shown in Examples 6c, 6d and 6e, culminates with a standard cadence in the Franco-Roman version, and elements of its contour are shared in the corresponding Old Hispanic cadence (at ‘ab eis’ in passage 1, ‘latus meum’ in passage 2, and ‘causam meam’ in passage 3). The contour similarities sometimes extend to the non-formulaic material that precedes the cadence, as at ‘custodiebant/custodientes’ (passage 2). We have included the Old Roman version of passages 2 and 3 as an example of the types of relationships found across the three traditions. While the Old Roman and Franco-Roman versions show the expected broad similarity of mode, emphasised pitches, and overall goal tones, the Old Roman melody is typically ornate. The Franco-Roman more closely matches the melodic density of the Old Hispanic.Footnote 52 Contour similarities between all three versions, however, are evident in the final cadence (Example 6e).

Example 6a. Contumelias, Franco-Roman, Pa 12044 (from Helsen, Great Responsories, appendix, 142).

Example 6b. Contumelias, Old Roman, passages 2 and 3 (Rome, BAV, San Pietro B79, fol. 92r).

Example 6c. Contumelias, passage 1, opening and cadence of phrase 1, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from Madrid 10.110, fol. 67r). (colour online)

Example 6d. Contumelias, passage 2, ‘Qui/et custodiebant/custodientes …’, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from Madrid 10.110, fol. 67r). (colour online)

Example 6e. Contumelias, passage 3, final cadence, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from Madrid 10.110, fol. 67r). (colour online)

A commonality in formulaic content between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions may be observed in three additional responsories, including Famulo meo, Ecce dominus veniet and Me oportet. Although Me oportet and Famulo meo exhibit density and contour similarities mostly in their opening passages, these parallels are noteworthy because the two Franco-Roman responsories use standard type melodies.Footnote 53 At the opening of Famulo meo, shown in Example 7, the two versions have a similar melisma on ‘meo’. As noted previously, Me oportet and Famulo meo appear to have been added to the Old Hispanic rite between the eighth and tenth centuries, and, for this reason, may well have been borrowed from the Franco-Roman tradition.

Example 7a. Famulo meo, Franco-Roman, opening passage (Einsiedeln, Kloster Einsiedeln – Musikbibliothek 611, fol. 27r).

Example 7b. Famulo meo, opening passage, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 246v). (colour online)

Thus far, we have shown that the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic traditions have some closely related formulaic content, sometimes used at the same points in their settings of the same text. While it is possible that they do so coincidentally, it is more probable that these parallels indicate common melodic ancestors, traces of which are preserved in each version. As we have seen, differences between the two traditions can also coincide with standard material, indicating that the melodies underwent assimilations to customary ways of singing within each tradition. In some responsories, however, the parallels between the two traditions coincide with both formulaic and non-formulaic material. Bethleem civitas (Example 8) shows evidence of a common ancestry for the Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman melodies both in density and in contour. Although the density diverges in a few places (‘Bethleem’, ‘exiet/prodiet’ and ‘eternitatis’), the parallels may be observed in much of the chant. Much of the Franco-Roman melody is non-formulaic,Footnote 54 and many of its contour similarities with the Old Hispanic coincide with formulas (‘summi’ and ‘egressus eius’). Both versions, moreover, have exact repetition, a structural parallel perhaps further suggesting common origins. At ‘in principio’, each version repeats material heard previously (at ‘eius’ in the Franco-Roman version and ‘Israhel’ in the Old Hispanic). Many of these affinities in density are shared by the Old Roman version, but it displays typical ornate tendencies in other passages (‘Israhel’, ‘in terram nostrum’). While it is typical to find a long melisma near the end of a responsory in all three traditions, all three versions place it on the last syllable of ‘nostra’, perhaps further evidence of their common ancestry. Exceptionally, however, the Old Roman version shows a contour similarity to the Old Hispanic melody at ‘dierum’ that is not matched in the Franco-Roman version. It is unclear whether the correspondences between the Old Hispanic and Old Roman versions are strong enough to posit a different direction of flow for this responsory (Iberia, Rome, Francia?), a possibility to be discussed in the conclusions. What seems clear is that melodies (not just texts) were transmitted between the Frankish or Roman sphere and the Iberian Peninsula. This may also be plausible in cases where both versions use formulas outside their expected contexts.Footnote 55

Example 8a. Bethleem civitas, Franco-Roman (Rome, BAV VS. C5, fol. 1v).

Example 8b. Bethleem civitas, Old Roman (Rome, BAV, San Pietro B79, fol. 12v).

Example 8c. Bethleem civitas, transcriptions of Old Hispanic, Franco-Roman and Old Roman versions (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 58v). (colour online)

In Hic qui advenit (Example 9), contour parallels between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic versions may be observed among both non-formulaic passages and standard cadences. For example, at ‘ipse solus’ (passage 1), we find the contour N/LHLH on the penultimate syllable. In both melodic traditions, this cadential contour often precedes the final syllable. The two melodies also share contours and density at the passage on ‘vestem praeclaram et omnis’ (passage 2). While the similarities between the two versions, particularly in passages that are non-formulaic, suggest that the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic melodies descend from a common ancestor, it is likely that both versions have been assimilated to familiar styles and ways of singing. For example, at the opening of the chant (not shown in the example), the Old Hispanic melody employs a very standard cadential neume combination (NS-NHLH) at ‘advenit’, reflecting a typical tendency to break the text into small units. The corresponding passage in the Franco-Roman melody lacks a recognisable cadence here.Footnote 56 Thus, we can posit that certain processes of melodic change took place in each tradition.

Example 9a. Hic qui advenit, Pa 12044, fol. 22r.

Example 9b. Hic qui advenit, passage 1, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 80r). (colour online)

Example 9c. Hic qui advenit, passage 2, contour and density (Old Hispanic neumes from León 8, fol. 80r). (colour online)

Conclusions

Having identified and examined hitherto unknown examples of liturgical and musical exchange between the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic traditions, we can now turn to their implications. These responsories demonstrate that more exchange of chant repertory between the Iberian and Roman or Frankish spheres took place than previously recognised. This exchange involved melodies as well as texts, and it took place through different routes and at different times.

Many questions remain. Can we determine the origins of specific responsories and directions of exchange? The multifaceted relationship between the Iberian Peninsula and pre-Carolingian Gaul makes answers elusive. In considering liturgical elements shared by more than one tradition, musicologists have tended to favour Gallican origin, whereas liturgical studies have often seen Iberia as the lender rather than the borrower.Footnote 57 Famously, elements of the Old Hispanic rite appear in the Irish liturgy, in Gallican sources such as the Bobbio Missal and in putatively Roman books such as the Old Gelasian sacramentary. Contrasting theories have been proposed to account for their circulation. Direct exchange of liturgical materials between Gaul and the Iberian Peninsula is conceivable in both directions, over a wide chronological span. Septimania (Narbonnaise Gaul) was part of the Visigothic kingdom from 462, and the remnants of its liturgy show many parallels to the Old Hispanic rite.Footnote 58 But scholars have also posited an indirect transmission of Old Hispanic liturgical elements, to Ireland and then to Gaul, via the Irish monks who settled there.Footnote 59 While these liturgical trade routes provide contexts into which our shared chants may fit, they offer no secure answers about the origins of the specific responsories examined here, or routes of borrowing. As Louis Brou noted long ago, all liturgies have diverse influences and ‘symptoms’.Footnote 60

There are suggestive points of contact between Iberia and Rome. Although the Suevic Kingdom in Gallaecia adopted a blend of Roman and Eastern practices in late antiquity, there is little direct evidence that the Visigothic bishops adopted Roman liturgical practice. Leander of Seville nonetheless developed a friendship with Gregory the Great during his exile in Byzantium, resulting in Gregory's dedication of Moralia in Job to Leander.Footnote 61 Their relationship hints at a mutual awareness of Roman and Iberian liturgical practices in the Visigothic kingdom.Footnote 62 In the late 640s or early 650s, Taio of Saragossa travelled to Rome to procure copies of Gregory's works that were unavailable in Iberia.Footnote 63 This visit may have coincided with the Lateran Council of 649 that established Mary's perpetual virginity. This, in turn, seems to have provided an impetus for the institution of the Old Hispanic Marian festival just a few years later (in 656),Footnote 64 the occasion for one of our responsories, Bethleem civitas. Could these contacts with Rome have resulted in the borrowing of this and other chants?

As the occasion for a large-scale revision of the chant repertory, the Carolingian liturgical reforms of the eighth and ninth centuries provided opportunities both for the retention of Gallican chants and for contact with the northern Iberian Christian kingdoms. Carolingian influence permeated the Iberian Peninsula in the ninth century, not only in the Catalan regions that adopted the Franco-Roman liturgy but also in the Kingdom of León, where the Old Hispanic liturgy continued. Communities of Visigothic refugees settled in southern France, and Visigoths such as Theodulf of Orleans, Agobard of Lyon and Benedict of Aniane assumed powerful roles in Carolingian hierarchy.Footnote 65 These connections provided opportunities for liturgical exchange in both directions, and some of our chants can be hypothetically fitted within this context.

Consistent with Ferreira's assessment of Conclusit, we see an Iberian origin as being plausible for many of the Lenten and Holy Week responsories, though a Gallican origin cannot be ruled out. As noted earlier, some of these chants are not present in the Old Roman manuscripts. Like Conclusit, several of them have shorter texts in the Franco-Roman tradition, presumably to conform to the length of a more typical Franco-Roman responsory. The lack of a typical periodic melodic structure among some of the Franco-Roman versions (such as Induta and Contumelias) also perhaps hints at a ‘foreign’ origin. A further circumstantial factor in favour of Iberian origin is the length and centonisation of these texts, typical of Old Hispanic Passiontide responsories. Finally, we have noted that the Franco-Roman melodies sometimes link more closely to the Old Hispanic versions than to the Old Roman ones, perhaps a further hint of non-Roman origin.

Another group of our chants (Sanctificami hodie, Me oportet, Famulo meo, Vir iste and Oranti/Orantibus) are seemingly later additions to the Old Hispanic liturgy, made between the eighth-century Verona orational and the tenth-century León antiphoner. These responsories may well be of Carolingian (or ultimately, Roman) origin. Some of them, such as Famulo and Orantibus, have a limited circulation in the earliest Franco-Roman manuscripts. Orantibus is also absent in the Old Roman manuscripts, raising the possibility that it is a Carolingian accrual to the Franco-Roman repertory. This case is perhaps strengthened by its melodic and modal instability. Given the absence of these chants in the core layer of the Old Hispanic repertory, a transmission from Francia to Iberia is possible, though there were opportunities for exchange in both directions.

The responsories examined here can also shed light on the nature of early medieval chant transmission, outside the Roman and Frankish contexts in which the question is normally considered. The transmission of these chants was varied, sometimes involving texts (or partial texts) only, and sometimes including melodies. For many of the chants under consideration, both versions are first witnessed in early, unnotated manuscripts, suggesting that the melodies were transmitted without notation. This may be why they were assimilated to the style and formulaic content of the receiving tradition. With the exception of Conclusit (in Ferreira's reconstruction), the Franco-Roman versions of these chants sound much like other Franco-Roman responsories on a moment-by-moment basis. As the melodies diverged from their common roots, they came to use elements that were typical of each tradition, which speaks to the power of habit. In the Franco-Roman tradition, the responsory formulas that permeated the night office became the ‘path of least resistance’ in setting long, centonised texts and reaching cadential goal tones. Given the frequency of standard cadential neume patterns in the Old Hispanic versions, we might posit a similar process of change in Iberia.

Stylistic assimilation, however, is only part of the story. Common melodic material may well have been shared across the Franco-Roman and Old Hispanic traditions, which exhibit some of the same cadential contours and text-setting strategies. In melodic density, the Franco-Roman melodies are often closer to the Old Hispanic versions than to the Old Roman ones. Were Old Hispanic and Franco-Roman chant, then, not all that different to begin with? In certain stylistic respects, perhaps. Yet the Franco-Roman responsories do share many of their standard elements with their Old Roman counterparts, as Helsen, Paul Cutter and László Dobszay have demonstrated.Footnote 66 Although the Old Roman formulas often proceed to different cadential pitches, resulting in different ‘roadmaps’, many standard elements are analogous.Footnote 67 Helsen's findings are consistent with the traditional view that Franco-Roman and Old Roman responsories have common Roman roots. Our comparisons, in fact, have shown that certain cadential contours could be shared among all three chant traditions: Franco-Roman, Old Hispanic and Old Roman. These commonalities of melodic language may well have facilitated the exchange and assimilation of chant melodies across liturgical traditions. Additional chants shared by these two liturgical traditions remain to be discovered, and they promise to stimulate further reflection on the development of repertories, oral transmission, the proportion of Frankish and Roman contributions to the repertory, and other questions that have long occupied us.