Utopia might always prove impossible. But it should not be entirely abandoned as a concept, or as a goal toward which work might be directed. It is hard to see how meaningful change could arise without at least some sense of utopian possibility. The architectural historian Nathaniel Coleman argues in this vein that simply “making-do with reality may be compensatory, but limits possibility, transforming apparent pragmatic agency into its capture by enclosing realism.”Footnote 1 Dealing with reality—often enough by making do—while keeping an eye on more magical possibilities has sometimes appeared, and has certainly been claimed, as the founding experience of making theatre. Theatres have seemed unique places where much might happen. If they are indeed special places, able to achieve special things, then they are not simply ebullient, but like Foucault's “heterotopias” able to combine dissident elements at the margins. Even when viewed at considerable historical distance, theatrical companies can appear truculent, wayward, and unsettling, even when they remain exploitative, manipulative, hierarchical—as many utopias are.Footnote 2 Inequities and exclusions based on race, sexuality, gender, and class are not absent from theatrical life. Coleman's point, however, is really to argue that that it ought to be possible to imagine sites and patterns of work that are not already foreclosed by the demands of the market, the law, or other forms of curtailment. It should be equally possible to imagine people coming together, bringing their skills, and working out how they might be combined. Reality and its utopian antithesis might then valuably contradict and coalesce. The combination is never easy. Imperatives, financial and otherwise, loomed large over theatres in Georgian England, as they do today. But improvisation and collective effort could both respond to and yet resist such downward pressures, to make something that is at least potentially dissident, as much a way of working as the work produced.

This article begins with these reflections because it risks telling the story of a single production, that of the opera Richard Cœur de Lion at Richard Brinsley Sheridan's Drury Lane Theatre in 1786. That production, though in many respects an instance of a fine and engaging collective effort, was equally a moment of eccentric, even sloppy making do upon which commercial realities pressed all too evidently. Although under pressure to deliver a successful production, Drury Lane appears to have been somewhat chaotic. Decisions were made last minute, or not at all. Actors pursued their own agendas, while the theatre's craftsmen and women were put under perhaps unnecessary pressure. Yet it worked out—Richard Cœur de Lion was a triumph—because the collaborative, though not well-coordinated workspace of the theatre permitted success amid the chaos. This way of working can be theorized, deploying Michel de Certeau's theorization of the nature of artisanal work, as coproductive and potentially dissident, thereby avoiding the closure to which Coleman objects.Footnote 3 To best reveal these practices this article introduces previously neglected resources, including financial records and the hugely revealing letters of Mary Tickell, whose somewhat contrary perspective reveals not just the effort and expense demanded by the production, but also the anxieties generated by the theatrical duopoly of Drury Lane and its competitor, Covent Garden. The imperative to succeed (or at least not fail) in such a competitive world ensured that theatre practitioners were forever aware of the need to satisfy audience expectations. Above all, Tickell's letters reveal the vibrant and conflicted inner life of the theatre, where different aspirations and clashing views of what could or should be achieved both propelled and inhibited the progress of all aspects of preproduction and ultimately the production itselt. Analysis of this material makes possible a new multidimensional examination of the social dynamics of eighteenth-century theatrical production.

I

While in Paris during January 1786 Frances Anne Crewe recorded that she had seen “a more beautifull, and splendid Opera,” than she thought had ever been staged in England, praising its fine “Gradation of Interest from the beginning to the End of it.”Footnote 4 She had seen Michel-Jean Sedaine and André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry's Richard Cœur de Lion, an opéra comique, first performed at the Comédie Italienne on 21 October 1784. The opera depicted Blondel de Nesle's legendary search for King Richard I, styled Cœur de Lion, imprisoned in Austria since attempting to return from the Crusades. It began with Blondel's arrival at the house of Sir Williams, a Welsh exile. Sir Williams tells Blondel of a mysterious prisoner held at a nearby castle. Blondel then sings “O Richard, Ô mon Roi” [Oh Richard, Oh my King], lamenting his monarch's loss and asserting his own loyalty: “L'universe t'abandonne; / Sur la terre, il n'est que moi / Qui s'intéresse à ta personne” [The universe has abandoned you / On earth there is no one but me / Who is interested in you]. Blondel then meets Sir Williams's daughter, Laurette, and discovers that she is in love with the castle's governor, Florestan. Countess Marguerite, King Richard's consort, and her knights arrive soon afterward and offer their assistance. Blondel goes to the castle alone, where he sings “Une fièvre brûlante” [a burning fever]. Richard sings in reply, enacting the most celebrated episode in the Blondel–Richard legend. Blondel is immediately seized by the castle's guards, and freed only when he proposes an assignation between Florestan and Laurette. Once released Blondel plans Richard's rescue with Williams and Marguerite. In the last act their combined troops storm the castle and free their king, ensuring a finale pleasing to late-century metropolitan audiences, who enjoyed medieval pageantry, high spectacle, and rousing music enormously.Footnote 5 It is a coherent piece of work for all that: Richard Cœur de Lion articulated Sedaine's admiration of strong kings, not least by making Blondel's unstinting loyalty its greatest drama. Florestan and Laurette's affair complements the royal rescue plot, while the repeated theme—“Une fièvre brûlante”—ensures a powerful sense of a romantic as well as political purpose.Footnote 6

Crewe may have recommended what she had seen to Sheridan, co-owner of Drury Lane theatre and her sometime lover. If she did, then she proffered an ambiguous gift. Despite her enthusiasm, it was not obvious that translating an ambitious and potentially contentious French opera to London would prove successful. English audiences were notoriously hostile to foreign plays, especially opera. Nor was kingship understood in Britain as it was in France. British kings could not claim political preeminence, too jealously did Parliament guard its privileges.Footnote 7 Nor could the “people” (however defined) be ignored or their loyalty assumed as still seemed possible in France. This would be a particular challenge for Drury Lane, given that theatre's somewhat Whiggish orientation.Footnote 8 Regardless and perhaps because of these challenges, both London theatres raced to produce the opera in the autumn of 1786, making the theatrical season of 1786–7 distinctive for its rival productions of Richard Cœur de Lion. The theatrical duopoly created by the 1737 Stage Licensing Act, which both assured the status of the two patent houses and locked them in a feisty “competitorship,” rarely produced such direct rivalry over a single play, still less a new work.Footnote 9 More often the contending managers organized their repertoire to counteroffer and thereby disrupt the plans of the other house; offering tragedy against comedy, or a new play against a proven crowd-pleaser. The records of the London theatres reveal, as Robert D. Hume, has underlined, ‘a vivid story of … fierce, even desrtructive competition'.Footnote 10 Actresses were frequenlty the medium of this contest, and its most active agents, as several recent studies have shown.Footnote 11 But such direct and open competition as occured in 1786 only happened occasionally. Most famously when John Rich and David Garrick had sparred with rival productions of Romeo and Juliet in the late 1740s, each adding a new and expensive element: Juliet's funeral cortege. The introduction of the cortege by both theatres, alonside the careful promoton of their star actresses, reveals just how important costly spectacle was to the competition between them, as it would be when Richard Cœur de Lion entered preproduction.Footnote 12

Despite the precedent set by Rich and Garrick, to have both houses hastening to gain the stage with their version of a new work was striking. In such cases it is probably an advantage to win the race. On this occasion it was Covent Garden that staged its production first, on 16 October, the performance starring Elizabeth Billington, Margaret Martyr, and George Inchbald. But Covent Garden had avoided the challenge posed by Grétry's score, replacing it with better-known English tunes, much in the manner of The Beggar's Opera. Leonard MacNally, who furnished the script, enlarged Sedaine's pastoral subplot, adding characters and some bawdy scenes as a carnivalesque counterpoint to the main action.Footnote 13 Such a heterodox approach did not disguise the often crass patriotism that dominated the Covent Garden production, never more in evidence than when the English knights are preparing to rescue their king and sing: “Soldiers strike home! / Britons ne'er flee,” they chorus, “Glory's our cause / Richard we'll free.” The echo of the patriotic standard “Britons Strike Home” was unmissable. The sentiment recurs when Richard's Queen Berengaria (MacNally corrected Sedaine in this respect) sings: “victory lies before us; / Liberty and Old England.” Throughout Richard appears as an exemplary king. MacNally's rewriting of “O Richard, Ô mon Roi” has Blondel hail “Richard, my friend, my patriot king.”Footnote 14 MacNally's additions struck some reviewers as contrary to the opera's elevated themes. The Morning Chronicle deplored MacNally's “violent professions of loyalty.” Despite these complaints and some other missteps, the production opened successfully. Takings were encouraging, even if aspects of the production remained uncertain or open to criticism.Footnote 15

It was Drury Lane, however, who eventually triumphed. When Drury Lane's production opened on 24 October newspaper paragraphs commended performances by Dorothy Jordan, John Philip Kemble, and William Barrymore. The singing was thought particularly excellent. The costumes, scenery, and music were equally admired, and praise was bestowed on the managers’ generosity for providing them.Footnote 16 The arrival of competing productions of the same opera provoked considerable excitement in the press in the weeks prior to the first performances. The Morning Post reported tellingly that the two theatres had “commenced hostilities” as early as 13 October and referred the “abilities of opponent actors,” tabulating both casts for their readers, as if they were rival teams. It would have been evident from the papers that the two theatres were intending to devote their most exciting talent to the project: Jordan and Kemble, for Drury Lane, were to play against Billington and Inchbald at Covent Garden.Footnote 17 These are puffs of course, in all probability placed by the theatres’ managers, but they nonetheless underline how much each theatre's efforts were animated by the theatrical duopoly. Competition was intense and to a degree unprecedented. The desire for artistic and commercial superiority prompted each theatre to invest in a risky and expensive production. Both Thomas Harris, manager at Covent Garden, and Sheridan at Drury Lane were eager to attract audiences and gain prestige by staging expensive, visually daring productions. Harris was especially keen to offer spectacle; in many ways it is the keynote of his management practice.Footnote 18 The competition was financial too. Each theatre needed to make money, at the very least cover its costs.Footnote 19

As theatre historians explore more and more of Georgian theatre's commercial as well as artistic endeavors, there is a need to better understand the place of crowd-pleasers like Richard Cœur de Lion in the repertory. Paula Backscheider, Jane Moody, John O'Brien, and Daniel O'Quinn have reappraised the spectacular forms of late century drama and the expensive means by which it was produced.Footnote 20 Drury Lane was certainly unstinting in its commitment: calling upon their director of music, Thomas Linley, whose talents allowed them to retain more of Grétry's rich and complex music—a fact appreciated by the European Magazine—while the experienced comic dramatist (and former General) John Burgoyne adapted the text.Footnote 21 Thomas Greenwood the scenographer and carpenter produced ambitious new sets, exploiting the scenic possibilities of a gothic romance set in a distant European location. The actors were, as ever, extraordinary. Beyond these individual abilities, the production depended upon a collective effort, through preproduction, rehearsal, and toward performance. Supernumeraries had to be marshaled, lines learned, and everyone costumed. This was not an enterprise to be undertaken lightly. Tom King as manager of Drury Lane, Sheridan as owner, Burgoyne, Linley, Greenwood, and many others had much to concern them. There was not much, as yet, that was utopian or dissident to witness. Legal and commercial realities were all too obvious; there was much with which to make do. Drury Lane had to beat Covent Garden, or at least not lose. The anxieties this pressure generated, and the dynamic combination of skills and initiatives brought forward in response to them, will be critical in the discussion that follows, not least as an unusually intense instance of what Joseph Roach has called Georgian theatre's “deep play.”Footnote 22

II

There was therefore much at stake when Burgoyne revised Sedaine's work. He needed to be mindful of the potentially dangerous politics of the original, the need to please audiences, and the theatre's capacity to replicate the success of the French opera. An experienced dramatist, Burgoyne made several changes: Richard's consort Marguerite became Matilda, while Williams became Sir Owen; the latter gained a second daughter, Julie. Most significantly, Burgoyne transformed Matilda's part, transferring much of Blondel's role to her. Consequently, it is Matilda who sings:

She performs these words disguised as a blind man, a decision which made it ideal for Jordan, a much-admired performer of breeches parts.Footnote 24 There is a political difference too: Sedaine's Blondel sings of Richard's abandonment with a subject's love; his declaration is the expression of a political passion—a desire to serve his king. Matilda sings not as a subject, but as his lover. The new emphasis on romance drains politics from the scene, replacing it with heterosexual passion. The substitution of power for love is most evident when Matilda sings beneath the castle walls, discovering Richard through the strength of her attachment:

The couple join their voices, singing together: “My [His] tender hopes recalling, / Have love and life restor'd.”Footnote 26 To make this love match work Burgoyne altered the crusader king's character, softening his manner and limiting his role to emotional effusions.Footnote 27 His transformation was too much for Horace Walpole, who complained that “turning the ferocious Richard into a tender husband is intolerable. If an historic subject is good, but wants alteration, why will not an author take the canvas, cut it to his mind, but give new names to the personages? It only makes a confusion . . . to maim a known story.”Footnote 28

Walpole's phrasing is telling but serves mostly to underline his deliberate noncomprehension of the Burgoyne adaptation's new direction. Burgoyne did not maim his story, he feminized it. Women, not heroic monarchs, are central to his gothic sentimentalism—a realignment with implications, as we shall see, for the ways in which the opera would be cast, staged, and marketed.Footnote 29 Burgoyne must have been proud of his work (or at least eager to have it recorded) as he ensured the speedy publication of a print edition, advertising it as a “Historical Romance.” A copy was in the hands of the company at Drury Lane by 23 October, while they were still rehearsing.Footnote 30 This was only days before the planned premiere. The Larpent manuscript and the print edition have been judged “virtually identical.”Footnote 31 However, the printed text provides longer stage directions, allowing the home reader to consume the text more easily. The print edition also provides the songs entire, including repeated choruses. The copyist at Drury Lane could not be bothered with such completeness. There is one notable difference: near the beginning of act III, Julie sings to her father. Her performance distracts him, allowing the romance and rescue plots to go forward. The song adds considerably to her role, but is absent from the Larpent save for the direction: “Julie/Sings.” The spoken line introducing the song also differs.Footnote 32 Evidently the text was not quite finished when it was sent to the examiner; but the song was decided upon, indeed, printed, shortly afterward. The shorter stage directions might point to unfinished business too. Decisions were probably still being made after the licensing submission and prior to the first performance. The development between the two versions suggests that the text submitted for licensing was not the final text: much still required working out. We need to be careful when using Larpent MSS as indicators of theatre practice: the Larpent is but one artifact in an open-ended process. This is especially true for Drury Lane, who were habitually tardy and slipshod in their presentations to the Examiner of Plays. Most pertinently, the evident looseness in the Larpent confirms that theatre is made rather than written: rehearsal prior to performance is a key site of mediation and experimentation rooted in temporal, financial resources.

Despite advances in scholarship on the material circumstances of Georgian theatrical production—particularly Tiffany Stern's work, which overturns the false assumption that rehearsals were limited or of little importance during the eighteenth century—most scholars continue to overlook the details on the preproduction process.Footnote 33 The potentially contested means by which a play becomes viable theatrical performance are multiple and complex. Several factors exert their influence: the creation of the script and any subsequent revision; the casting, requiring negotiation with actors, who may have their own needs or prove difficult; the manufacture of scenery and costumes, which incur costs; and, in a commercial theatre, uniting all, the delineation of audience desires so that revenues can be guaranteed. The internal economy of a commercial theatre like Drury Lane was a variously enacted endeavor with authority often deferred or devolved; especially so when a production called for music and scenography, or the casting of crowd-pulling celebrity actors.Footnote 34 Discovering how decisions were made and how they were implemented is vital; but it is important to do so in ways that are sensitive to the plasticity of processes that first constrained but ultimately compelled through the exigencies of business, celebrity, and profit. It is necessary therefore to understand the relationship between these pressures, and their role in shaping production. The theatres’ needs and demands were responded to, and indeed counteracted, by forces from within Drury Lane. De Certeau describes how work practices, the behaviors of artisans, employees, workers of all sorts, become independent, adaptive, even resistant. There is an element of disobedience as well as making do. Like authors, managers might seek control, but their efforts are only partially successful; de Certeau's method emphasizes the role of “unrecognized” workers as the coproducers of culture. In this instance the rehearsal process and backstage activities clearly played a tactical (in de Certeau's sense of reflecting relative weakness within a known hierarchy) yet pivotal role, one that is not recoverable from a reading of the Larpent MS or any other text. It is to these efforts that it is now necessary to turn.Footnote 35

III

Finally getting round to it, Drury Lane had submitted its script for licensing on 16 October, the day Covent Garden's version premiered. The rival theatres were now almost fully engaged. Press coverage was extensive. Articles anticipating the Drury Lane production soon filled not just paragraphs but whole columns. The theatres were active in this process, gaining from the publicity the rivalry necessarily produced.Footnote 36 Drury Lane's belatedness put the theatre under pressure. Though they had the advantage of a better script and a superior music, to realize this advantage required deploying and corralling their staff, as well as some adventitious, even haphazard making do. A perspective on Drury Lane's tribulations emerges from the archive of Mary Tickell letters, now held at the Folger Shakespeare Library. It is from her that I have already taken the term “competitorship.” Tickell was the daughter of Thomas Linley; her mother, also Mary, was the wardrobe mistress. Tickell exploited the opportunities these connections afforded, attending performances and rehearsals, including those for Richard Cœur de Lion, where she offered her opinions despite having no designated role. She recorded these encounters writing to her sister, Elizabeth Sheridan. Her purpose at least in part was to prompt a response or better, action, from the theatre's owner, Richard Brinsley Sheridan.Footnote 37 Tickell exposes the sometimes tense relationships between the management and staff at Drury Lane. She tells her sister who was doing what, and who might do better. She is clear-sighted about the business of running a theatre: it must make money. Tickell reports proudly, for example, the successes of a recent command performance, by Sarah Siddons, and the continuing success of the comedic afterpiece The Romp, owing entirely, she claims, to Jordan's performance. Actresses brought in money: “more than £300” in the case of Siddons's performance in James Thomson's Tancred and Sigismunda.Footnote 38 Burgoyne's carefully adapted Richard Cœur de Lion would seem a smart choice in this context. However, the story Tickell imparts is uncertain of success. The chaos, delay, and indecision she reports reveals much about the way in which Drury Lane operated, working from dispute and dissension and through tribulation to triumph.

Tickell's first letter concerning Richard Cœur de Lion is dated simply “Friday,” but her reference to a “Michaelmas Goose” means that it must be Friday, 29 September 1786. She reports that the musical part of the “first act . . . is to be rehearsed Monday.” Scheduled for 2 October, this first rehearsal is more than three weeks before the premiere. That work has been devoted to the production so early underlines its importance. Although Tickell reports progress, she worries that “the [Covent] Gardeners are working away as fast as possible—and have some how or other bungled upon our idea . . . of changing the friend to the Mistress—& Mrs Martyr is pitched upon.”Footnote 39 Tickell refers to the alteration of the Matilda part, revealing how duopolistic competition is enacted through actresses, who are pitched against other. It is this, precisely and particularly, that she understood as the “competitorship.” She understood vividly the implications that Burgoyne's adaptation had for the way in which the opera could be staged—not least the prominence of actresses. The new role of Julie, Sir Owen's second daughter, was taken by Maria Theresa De Camp, making her Drury Lane debut. Tickell enthuses: “I admire the idea of a part for Decamp of all things,” knowing that it adds to the interest of the piece, while developing a new performer. Her expectations confirm Nussbaum's assessment of the importance of actresses and their publicly performed rivalries.Footnote 40 For a new production, which might easily go awry, actresses, especially if young or famous, generated valuable interest in the press, helping to ensure ticket sales. The place they occupied on the stage and in the audience's mind is critical. Even so, their introduction required careful management within the burdens and risks of the commercial “competitorship.” This point requires further theorization, but it is clear that casting of the production was sensitive to the commercial pressures that the duopoly developed as a consequence of its inherent complexity: stable because the Licensing Act limited the number of theatres, but highly unstable in its internal competition. Anxiety and pressure resonate throughout Tickell's correspondence. By mid-October she knew that the Covent Garden production was leading the race; keen to reassure her sister, she got tickets for the premiere: “I shall be in such agony if it is good—& yet I think there is not much chance with Mr MacNally's alterations and additions w:ch I see are publicly advertised with new music by Shaw . . . you may depend upon having a very impartial Account of its merits or faults.”Footnote 41

Animated by her self-appointed responsibility, and clutching “a new pen for the purpose,” Tickell wrote a superbly detailed account the next day, relishing the production's deficiencies and improprieties.Footnote 42 Alongside her own theatrical knowledge, Tickell based her judgment on her recent reading of Sophia Lee's The Recess. Lee's novel, which had given rise to a “fine cry,” suggested how the medieval past could serve as an opportunity for pleasurable historical difference, epitomized by the return of chivalry. MacNally's work completely lacks this dimension. It is, she explains, a “vulgar, stupid representation” with little “resemblance” to “the French.” The performances by male actors, central to MacNally's bawdy revisions, are specifically censured: “instead of our exiled Sir Owen, they have [John] Quick as a dirty vulgar Keeper of an Ale House, before whose Door the piece opens—with a very faint view of the Castle in the Back-Ground.” The want of spectacle is compounded by the cast's vulgarity. She rattles through them, admonishing each in their turn: Ralph Wewitzer, who played Bergan, “is a Country Clown . . . quite new to the piece, as is . . . Mrs Kennedy, a sort of stupid Mrs Bundle in [Charles Dibdin's] the Waterman only she chose to leave out most of her Songs, Lauretta made a pert bold country Girl not very unlike Jenny in [Dibdin's] the Deserter abusing her clod Pate Lover.” Worst of all, is the character of La Bruce (played by John Edwin), he is “quite a Creature of the Author's imagination in a Dress something like Touchstones—he is called Berengaria's Valet, tho’ I saw nothing he came in but to babble his nonsense & delight the Audience with his Vulgarity.”Footnote 43 The dignity of the gothic past has been traduced, as much by smut as by incompetence. Beyond this polite regulation, Tickell's commentary exhibits her deep knowledge of the repertoire: it rests on comparisons and allusions she expected her sister to comprehend with equal facility. This confidence is poignant testimony to their shared, though now suppressed skills as performers. They knew what they were talking about, as their letters always make plain. But most of all Tickell offers a gleeful revelation of tumble and mess at Covent Garden. It should all be better: but she is glad that it is not.

While Tickell's gothic-inflected sense of gendered proprieties gave zest to her appraisal, her main concern was to judge a commercial rival, to appraise the “competitorship,” and the means by which that battle might be won. This meant attention to the performance of Covent Garden's lead actress, Elizabeth Billington. (Tickell had been wrong to claim Martyr in the role; she played Lauretta.) Billington is described forensically. What is striking about Tickell's commentary is the extent to which distaste for the actress's peculiar costume develops into a wider criticism. Historical accuracy is not her sole concern, but it underwrites an admonition directed at the actress herself:

I must introduce you to Madam La Countess or as they call her Queen Consort—in the Middle of a High Wood she is discover'd in a very pretty Grey Sattin Dress with an immense Plume of Feathers on her head, leaning on a very jolly Confidante in Blue Sattin—she comes forward, but what she said, I did not hear, & then sings the Air beginning “once more my Lyre”—w:ch by the Bye are beautiful words, . . . prettily set too, I believe by Shield—in this scene, Edwin and Quick join the Lady and invite her to the Public House (the audience in amaze all the while who this fine Lady sh:d be, or how she got into the Wood—but by the bye Ma'am—Ecod out she comes in the ale house the finest Queen you ever saw with a Train from one side of the Stage to the other, & all over Glitter—you may think perhaps it look'd a little odd to see her talking with Quick in his blue apron but I can't help that.Footnote 44

Behind her claims for inappropriateness of “Grey Sattin” is a critique of Billington's desire to dazzle. Her dress and plume enact what de Certeau terms “la perruque, ‘the wig’”: the “worker's own work disguised as work for his employer.”Footnote 45 He cites a variety of artisanal subterfuges and secretarial appropriations; the category applies here even as its disguise is seen through. Billington has performed more than her contracted work; her performance, essentially as herself, as costumed celebrity, eclipses her performance as Berengaria. She has attempted an act of visual dominance, a coup de théâtre, against character and historical precedent. This superadded work of self-display, comparable to Quick's vulgarity in its intrusiveness, is too disruptive. In Roland Barthes's terms, Tickell has witnessed the actor all too clearly, preventing the operation of a myth.Footnote 46 Furthermore George Inchbald, playing Richard (similarly overdressed), cannot sing, provoking laughter. Tickell closes triumphantly: “there was a good deal of hissing when the Curtain drop'd.” Her solitary note of praise is for Blondel's harp, which was “very picturesque & we mean to have one.”Footnote 47 Her attention to this detail confirms her reliance on gothic mythmaking and its signs, an enthusiasm that underwrites her report of rehearsals and eventual performance at Drury Lane.

But there were limited grounds for confidence at Drury Lane at this point. The day after the Covent Garden premiere, 17 October, Tickell sent her sister “word of our side.” There is some good news to impart: Kemble, she writes, is “vastly delighted with his part & my Mother says has the sweetest voice.” Her father is similarly “delighted with De Camp.” But there is confusion about whether the opera would work best as a main or afterpiece.Footnote 48 Covent Garden wrestled this problem: for its first four nights their version served as a mainpiece, but it was reduced to an afterpiece for the fifth and all subsequent performances.Footnote 49 The choice between mainpiece and afterpiece was a critical decision with significant implications for how the theatre organized its repertoire, so it is surprising to find each theatre unable to decide. Tickell regards the problem as only partly technical. It is more obviously a consequence of inertia and ineptitude:

They are one and all violent about it being a First Piece—I don't know what to say about it, [Sheridan] must determine but I wish he w:d let them know his final Determination as at any rate it is quite necessary it sh.d come out as soon as possible. [Sheridan] has had all the Objections to its being an afterpiece . . . stated to him, therefore pray let him decide—for we are in a great hurry—we have wrote one verse for Decamp—& must [find] another if we can—but pray send [Sheridan]'s word & let something be fix'd. Texier, King, Kemble, Smith—they are all of the Opinion that it should be a first Piece—& my Mother says we don't want afterpieces—but let [Sheridan] use his own judgement about it—there must certainly be a few additional Songs as a first Piece . . . the sooner they are set about the better.Footnote 50

It is already too long: “they say it will be two hours in Representation & therefore twelve o clock before it is over.” She is exasperated with Sheridan especially. Her letter assumes that he has the final word, or should demand it. She writes imploringly, hoping to gain his attention: “I hope [Sheridan] fix'd everything about the Scenery for I shall die if it has not a good effect.”Footnote 51 The state of the scenes is critical, not least because new scenery was an expense not always undertaken. However, it is not clear what Tickell means. She could mean that Sheridan had agreed the financial outlay, or that he had commissioned them directly, or even that he had submitted design ideas of his own. It matters less which option is correct than the realization that, even at this late hour, nothing is “fix'd.”

Sheridan's role at Drury Lane at this juncture is unclear. Though he owned the theatre, he was not in charge routinely, at least not officially and certainly not on a daily basis. King was the manager at Drury Lane in 1786. The choices Tickell describes were his responsibilities, though she never thought him very competent.Footnote 52 Cecil Price suggested Tickell's letters disclosed that Sheridan had a “considerable hand in the production if not the actual writing” of Richard Cœur de Lion. He certainly sought a role, however vaguely. Tickell acknowledges the arrival of some material from him—“poetical alterations” she calls them—but dismisses them as mistaken.Footnote 53 Her correspondence more obviously indicates a shared and familial effort, one in which she and her playwright-satirist husband, Richard Tickell, played a role. Although there is the suggestion of guidance from Sheridan, Tickell is annoyed by his intermittent attention.Footnote 54 Sisterly collaboration is much more evident. Elizabeth Sheridan's letters have not survived; but Tickell's side of the correspondence indicates that they discussed the music in detail and may have supplied their composer father with material. Tickell certainly asks her sister to send Linley additional music: “any thing operatical must do well,” she suggests.Footnote 55 There is a dynamic operating here, both consultative and competitive. The two women are working together, unofficially but diligently; it not surprising therefore that the Duchess of Devonshire thought they were responsible for the work entirely.Footnote 56 Less speculatively, their exchange occurs after the play had been submitted for licensing, further suggesting that the production was still evolving after that point. There was certainly much to finish, determine, and adjust, especially concerning the singing. The theatre is making do, botching its way along. Tickell's next letter supports this view. This crucial letter took three days to write, Tickell beginning it at some point during Wednesday, 18 October, and writing again on Thursday and Friday morning before having it franked and posted. She begins: “I have just dispatch'd T– [Richard Tickell] to the Rehearsal,” though, she confides, “my Lord is rather delicate about interference. . . . I don't think he will be entirely useless—we have fabricated another verse, such as it is, for Decamps and I have charg'd my Father to put a little tic tac Accompaniment, but whether he will or no, is another matter.” More worryingly, “they are still in doubts about it being a First piece.” The sticking point is the second act, which, though “very interesting,” does not have “music enough.” She asks that Sheridan take the final decision, but probably did not expect he would, and suspecting him of wasting time with his aristocratic friends.Footnote 57

Nor are the performers ready. Jordan “continues very imperfect but I think if this was advertised for a Day she w:d take care to be ready for her own Credits sake.” The idea that Jordan runs to her own timetable recurs when Tickell complains (with her mother's concerns on her mind) that she dislikes Jordan's costume change prior to the storming of the castle. It is, she claims, implausible and impractical: “She says, there will be plenty of time for her, while the Assault is going on. To change her Dress, & make her appearance to her Lover in a fine flowing Robe of White Sattin—it strikes me that such an attention to her Dress at the time she must be so strangely agitated for the safety of Richard w:d be very unnatural.”Footnote 58 Tickell makes it clear that the burden of the duopolistic rivalry falls most heavily on the shoulders of the actresses each theatre employs.Footnote 59 Part of the armory chosen by the actresses for the conflict is their dresses (which is a key part of their performance in character, and as celebrities). Tickell reveals this arming even if she remains stoutly unsympathetic. She sees only la perruque: Jordan working additionally for herself. By the time Tickell has finished writing her account, her husband has returned with news. He reports that “the scene between Richard and Matilda is charming, & Greenwood has executed inimitably the great Masters Designs—Decamps is likewise charming—but I find the song is too slow for her, so I must give my Father a fillip. Mrs Crouch wants to rival the Billington I suppose in a fine flourish Bravura—but it is done as an afterpiece, it w:d be surely madness to add a note or word to the present length.”Footnote 60 Tickell remains concerned with how the production is progressing, or rather not progressing. The date for the premiere is slipping back. Worse, the Covent Garden production has been commanded by the king. Although their production continues only with what she derides as “dull safety,” she is anxious because Drury Lane's version is “not even advertised for any time.” Managerial confusion is referenced repeatedly: a state of indecision not helped by Sheridan's failure to communicate and made worse by Tom King's allowing Anthony Le Texier, installed by Sheridan at the King's Theatre, to swan about “quite the Master of Cappello” while running up expenses. Everything is muddled and mistaken. Defeated, she concludes admitting that Jordan is so attached to her white satin dress that she cannot dispute it with her any further.Footnote 61

IV

Like the young Jane Austen, Tickell is a partial and prejudiced historian. She is never ignorant. Nor does she lack access to the scenes she describes. Above all, Tickell is protective of her family's interests. Having been a professional singer, she is familiar with theatres. She knows how they could and should work.Footnote 62 She provides detailed, precise information, reporting directly on events at Drury Lane. Her acuity is evident throughout the lengthiest letter on Drury Lane's Richard Cœur de Lion, which reports the “night Rehearsal” and subsequent premiere. A night rehearsal was a sizable investment. Drury Lane did not have designated large-scale rehearsal space. The only place to rehearse en masse was the theatre itself, and to rehearse at night meant closure. Drury Lane was consequently “dark” on Friday, 20 October. Drawing slyly on familial knowledge, Tickell judges Crouch's performance of Laurette's song in act I “a great deal too slow, but I fancy my Father alter'd the time according to your Direction.” She continues:

The Rondeau . . . between Mrs Jordan & Mrs Crouch was too slow—my Father and I, had a fine squabble when we came home, not so much about this, as Mrs Jordan's being singing Oh Richard! Not according to contract—she begins  —and pronouncing the last Syllable very broad makes the stress sound exactly like the French, w:ch you know is exactly wrong. You know how monstrous obstinate our good Parent is; so whether my violence will do any good or no I can't tell.Footnote 63

—and pronouncing the last Syllable very broad makes the stress sound exactly like the French, w:ch you know is exactly wrong. You know how monstrous obstinate our good Parent is; so whether my violence will do any good or no I can't tell.Footnote 63

Father and daughter clearly had quite a scene. Most importantly, Jordan's performance of “O Richard,” not “according to contract,” but in her own manner, perhaps with her own purposes and audience in mind, is the clearest example of her independence as professional and celebrity, able to define her own work and to perform it. Linley appears to be unable to stop this, much to his bossy daughter's outrage. Elsewhere she laments that:

Father mistook entirely the intervention of [Sheridan] about Decamp's Song and told T– [Richard Tickell] it was to be an invitation to the Pilgrim [i.e., Blondel] to stay to partake of their merriment—w:ch we affected at a Rate, & then found by the Dialogue it was to be a Song she had studied for the purpose—it was too late to be alter'd & as it is a pretty little acting childish Song, I don't think it matters much.Footnote 64

Such fluidity of making do and last-minute rushes of inspiration seems endemic and a little desperate. New material is added or sought, and adjustments made only days before the production opens, and seemingly not very thoughtfully either: ‘anything operatical will do'. The grasping hotch-podge nature of this creative process is contrary, and very obviously so, to the singularity of purpose and assurance implied by both the licensing process and Burgoyne's eager publication of the text.

The scenery, which remains unfinished, is another source of anxiety for Tickell, as are the costumes:

poor Greenwood was in woeful Fright that so many men in the last Scene w:l spoil his Scene w:ch is a very fine one—so many says my Mother? Why how many?—why Ma'am replied Johnson, Texier has ordered Dresses for sixty six, Pioneers & all—you can easily conceive my mother's Rage at this intelligence—in short half the number will be found more than enough to release [King] Richard.Footnote 65

Theatre workers like Greenwood and Mary Linley are often voiceless in accounts of Drury Lane, so it is pleasing to have their anxieties recorded, if not quite accepted by Tickell. Later she reports that her father has been prevailed upon to cut “the long Symphony at the end I believe of the first Act, w:ch had nothing to do with the Business and now I think it will do very well in point of length—if they make haste [with] the Scenes.”Footnote 66 Tickell's confidence is justified when she attended the first three performances. She reports the opera's success excitedly; it has, she coos, “gratified’ even “the most sanguine Expectations.” “What delighted in all more than anything” was that the

Carpenters exerted themselves so much, that there was not the least degree of impatience shew'd by the audience before the 2nd Act opens with such a wonderful Alteration of beautiful scenery, that it seem quite the effect of magic to have had it there, so soon—I know not where to begin, or w:ch part to give the Palm of Praise so excellent was every part of the Performance—and as to the Battle, I assure you it was so very much in earnest—that T– [Richard Tickell] told me, in the front Boxes the People were quite elbowing one another in expressions of animation & admiration—Governor Wrighten I understand had the Management of this admirable Siege, & most entirely does it do credit to his taste and knowledge of Stage effect.Footnote 67

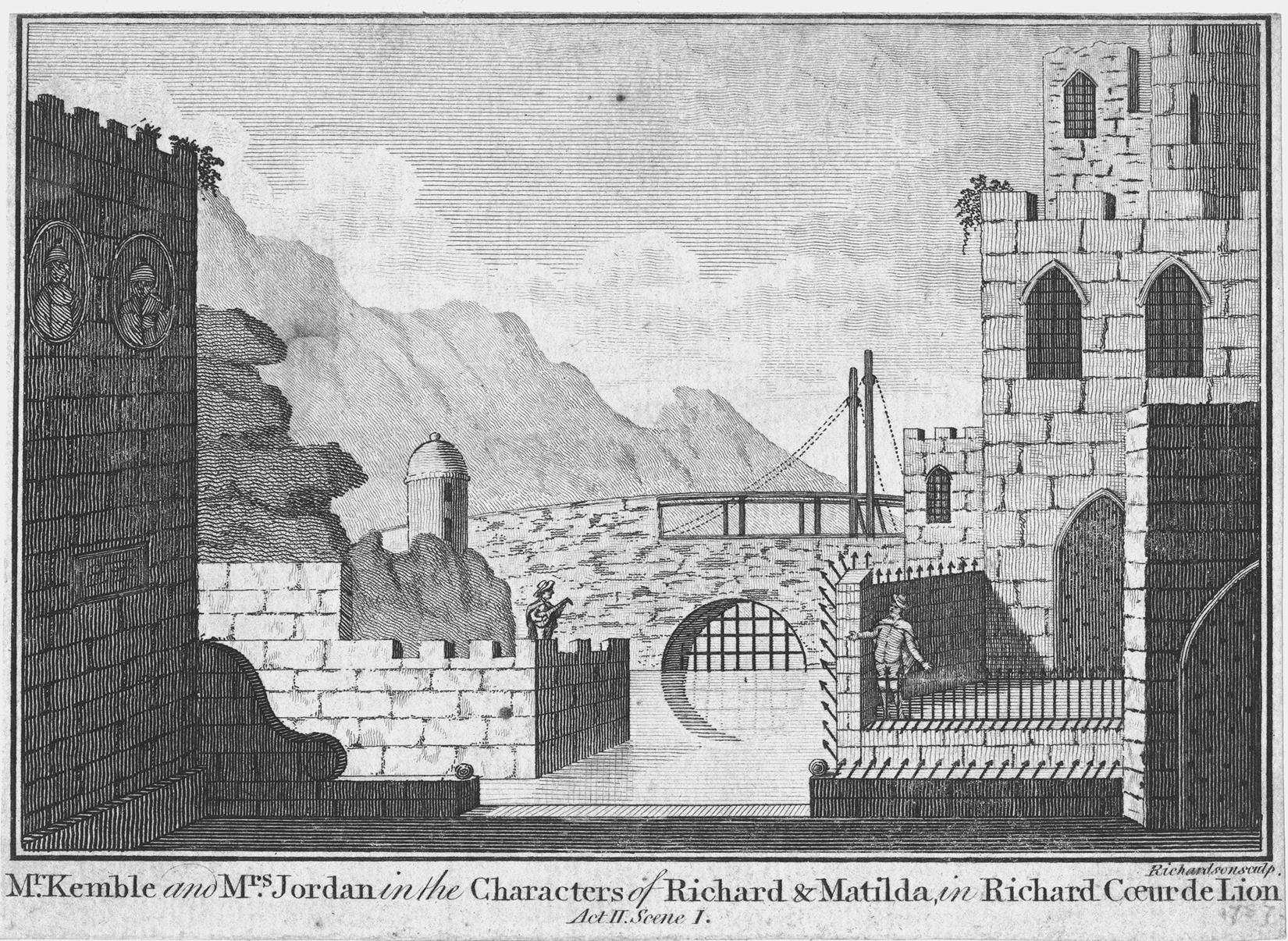

Work had come successfully to fruition. Something emphatic even potentially utopian had been realized, but note who is responsible for this “magic.” The efforts of James Wrighten, officially Drury Lane's prompter, had a long genesis. The “Assault,” as Tickell terms it, a key part of the final spectacular scene, had been rehearsed separately a week earlier, indicating just how much resource was allocated to it.Footnote 68 Helpfully, an image of the castle set has survived (Fig. 1). Although the image is stark and rather naive, it reveals the gothic massiveness of Greenwood's design. It would take a lot of personnel to fill it convincingly. Drury Lane's Journal, a fair copy of the nightly account books, provides corroboration. The entry for the 21 October (following the night rehearsal) records significant payments to Greenwood and to the carpenters: £13 3s. 8d., including for “extra” work. The entry for the day of the premiere, 24 October, contains payments for “Carpenter's Bill & extras & rehearsal,” in total, £37 3s. 4d., while £1 10s. is paid to John Foulis for “Music Copying.” There is also over £19 laid out for “Supernumeraries,” in this case for additional cast members, recruited from the backroom staff, necessary to storm the castle in the final act.Footnote 69 Sheridan had lowered the rate for supernumeraries to one shilling in 1776 (down from 1s. 6d.).Footnote 70 Though probably a weekly total, the figure of £19 is still exceptionally high, indicating a mass deployment, one that served to render the final scenes all the more impressive. Precisely who the supernumeraries were is likely to remain obscure, though elsewhere in her correspondence Tickell reports the giddy excitement with which the theatre's tailors were costumed to appear in the Shakespeare-pageant The Jubilee, one even appearing as Cardinal Wolsey.Footnote 71 As elsewhere in Tickell's account, apparent inclusion may mask exploitation, a binary too frequent in the experience of theatrical supernumeraries; but it is probably worth remaining open to other possibilities.Footnote 72

Figure 1. Richardson, Mr. Kemble and Mrs. Jordan in the Characters of Richard & Matilda in “Richard Cœur de Lion,” engraving (6½ × 4⅜ in.), London, 1787. Call no.: ART File B957.2 no. 1. Digital image file name: 21286. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.

The investment required to create the spectacle demanded by Richard Cœur de Lion was huge. To storm the castle required an army, who needed to be dressed, drilled, and paid off. Tickell's warm description of the supernumeraries’ costumes after the first night underlines the scale of investment, contravening her mother's parsimonious instincts: “I assure you they looked like they could fight any battle”; “such knights have never been seen since the age of Chivalry.” The sight of them storming over the bridge, she writes, produced a “very picturesque effect.” Individual performances were also excellent, including Jordan. Tickell even admits the “good stage effect” achieved by her dress change as she comes “through the Soldiers over the Battlements.”Footnote 73 The prison scene, when Matilda sings with Richard, was a particular triumph:

I believe you might have heard a Pin drop in the Upper Gallery—but when the Guards seiz'd Matilda & Kemble was oblig'd by the Governor to retire (& by the bye [Kemble] acted that part particularly well) the whole of the Situation struck so forcibly on the minds of the audience, that it was like an electric Shock—and they gave such repeated Applause & Bravo's that it was quite charming. I never saw an audience applaud so properly, and with such genuine feeling in my Life—Mrs Jordan was frighten'd excessively . . . but she was overpower'd with Applause.Footnote 74

After seeing the opera for a third time, she boasts that Jordan “is better and better as she gets more mellow and perfect in her part.”Footnote 75 This last comment may indicate that, for Tickell, Jordan's performance now conformed to both her required dramatic role and gender identity. Tickell confirms Jordan's accommodation (she is now acting “according to contract”) when she reports the audience's applause for the poignant scene between Matilda and King Richard, Jordan and Kemble, kept asunder by fate and the officiousness of the castle's guards. The focus of sentimental gothic on the predicament of a woman at once active, yet engagingly vulnerable, achieves much in the way of theatrical affect. Medieval history is recast as romance; in a simultaneous movement Sedaine's royalist politics are sidelined in favor of modern chivalric pleasure, to which the Drury Lane crowd responded quite rapturously, demanding many encores.Footnote 76

V

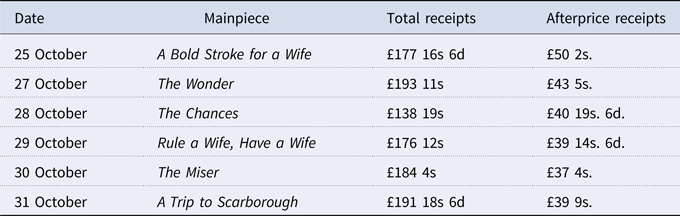

Eventually a very good job had been done. The opera was staged thirty-eight times, far more than Covent Garden's version, which soon proved unprofitable in the face of superior competition. Only the closure of the theatres after Princess Amelia's death interrupted the Drury Lane production's lucrative run.Footnote 77 Receipts were consistently high: nightly takings of more than £200 were frequent. Many audience members paid only the afterprice, attending the theatre late to see Richard Cœur de Lion regardless of the mainpiece.Footnote 78 First-night takings were impressive; £226 in total with £32 14s. paid at the afterprice rate (the mainpiece was The Winter's Tale). For the six nights prior to Princess Amelia's death revenues were more than respectable (see Table 1). The consistency of the afterprice receipts is striking. Receipts for the mainpiece vary more significantly, reflecting the relative popularity of each play and its leading actors. Casting decisions, as Roach argues, were critical to the “orature of stage production.”Footnote 79 When star actresses appear in the mainpiece, revenues rise; pairing Richard Cœur de Lion with Love for Love or A Trip to Scarborough proved lucrative as Jordan appeared in both, alongside Farren. There was personal support for Burgoyne too. His benefit night, 20 November, when Richard Cœur de Lion appeared after The School for Scandal, took a princely £220 4s. 6d. Higher receipts were obtained when the opera appeared with The Heiress, Burgoyne's comedy from the proceeding season: 30 November, for example, netted £285 7s. 6d., and the double bill took £238 15s. 6d. and £213 4s. 6d., respectively, when repeated on 20 and 27 February.

Table 1. Drury Lane Revenues, 25–31 October 1786

Source: Charles Beecher Hogan, ed. The London Stage, 1660–1800: A Calendar of Plays, Entertainments . . . Part 5, 1776–1800, 3 vols. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1968), 2: 929.

Such high receipts support Tickell's repeated if exasperated view that Jordan was the crux of the production; perhaps because, in many ways, Richard Cœur de Lion is about her and how she might be presented, artistically and commercially. The business was not straightforward. Tickell discloses an essential paradox. The theatre must organize the sale of someone—their star—who was already possessed of the idea of selling herself. Jordan knew how to value herself—rather too much, as far as Tickell was concerned. She had acquired celebrity astonishingly fast. After her first performance at Drury Lane, Tickell judged her a “valuable acquisition” who would prove “a treasure to us.”Footnote 80 The language of commerce is used precisely; freighted with an awareness that keeping a celebrity (by keeping them happy) invariably proves expensive. White silk dresses do not buy themselves. Managing Jordan and integrating her into the repertoire was a challenge. Drury Lane already had two leading actresses, Siddons and Farren, though neither succeeded in the comedic styles Jordan made her own, nor would they provide the sexual charge of Jordan's cross-dressing. Jordan's performances as Miss Hoyden, Miss Prue, or Viola catered to these pleasures and gave her a range of parts. But there was still a need to provide her with her own new roles. Burgoyne had created leading roles for Frances Abington as Lady Bab Lardoon (in The Maid of the Oaks) and for Farren in The Heiress. Now notorious as a defeated general, Burgoyne might be valuably reconsidered in terms of his ability and above all willingness to write prominent roles for star actresses. He had wanted Jordan for The Heiress, but the management refused his request, deeming the part too small for her.Footnote 81 Richard Cœur de Lion answered the demands of both parties: Jordan gained a role while satisfying Burgoyne's desire to have her star in his work. Addionally, the role of Matilda enabled Jordan to develop a more “plaintive” and artfully natural mode of feminine performance, which would help extend her career.Footnote 82 To sing “O Richard” as she did was central to process, something that Tickell did not quite understand, believing it to be a performance of something beyond the required role.

Though wrong about Jordan, Tickell discloses an immense amount about how Drury Lane staged Richard Cœur de Lion. She reveals how soon and how often Burgoyne's text was placed to one side or was only ever to serve as the initial basis for rehearsal. Adjustments were made and songs added to create greater parts for other actresses. Other matters are finessed, or even added late in the rehearsal process, and probably afterward. None of this additional material—whether it was good or bad—survives, and we only have Tickell's account of it. Her sisterly though sharp bulletins are forensic in their detail, serving as a reminder that we need to balance an account of the ambitions and intentions that might be thought to derive from the playtext, as well as its competitors or antecedents, with an appreciation of what might have occurred in rehearsal. In this instance the process was long and disputatious: dominated by a need to find roles for cast members, roles that suited or extended their abilities and reputations, and which brought in paying customers. Jordan's casting is indicative of their ambition, equally Kemble as King Richard, though not an obvious choice for a singing role. Richard Cœur de Lion enabled the theatre to bring forward other players, notably De Camp—another player brought into the team. But theatre is always about more than those onstage. Drury Lane relied on the talents of the Linleys, Wrighten, and Greenwood, their skills ensuring Drury Lane's superior production. This work, especially its success, might be considered as utopian, or at least somewhat joyous, insofar as it exceeds, and in a measure evades, the requirements, strictly understood, of theatrical commerce. The duopolistic imperative—the need to succeed—is met, but something more occurs. Jordan “gets more mellow” but keep her perruque; perhaps even the tailors, dancers, and carpenters maintain some sort of self-possession. On this point, it is hard to be sure, and perhaps wisest to doubt. But when the cast and the backstage staff swarm onto the stage for what Tickell calls “the Assault,” clad in their medieval best, there is a sense in which they have come together to rescue not only Richard Coeur de Lion himself, but the whole enterprise. This is more than good practice, better than simply making do. Tickell both sees and denies this potential. Her exasperated perspective is not always appreciative of discordant possibilities. Amid all this bustle, Sheridan's role is difficult to define, harder to pin down. He emerges from Tickell's account as an unreliable but necessary figure. Without a willing or commanding central authority, the culture and practice of Drury Lane is varied and mutable, subject to daily emergencies. It is centered on the interaction of different members of the theatre's staff, both before and behind the curtain. With a somewhat utopian flourish, though this is not without evident limits, Drury Lane's social production of theatre overcomes its central organizational failures. Management may be weak, but the wayward, truculent, and much put-upon staff succeed anyway.

Robert W. Jones is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies at the University of Leeds. His work focuses on the political and literary culture of Georgian Britain, especially Drury Lane theatre and its owner, Richard Brinsley Sheridan. He is currently preparing for publication a book entitled The Theatre of Richard Brinsley Sheridan: Drury Lane, Politics and Performance 1775–1787. He is also the coeditor (with Martyn Powell) of The Political Works of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, which will be published in five volumes by Oxford University Press.