Introduction

Self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) has been increasingly utilised as a psychotherapeutic training intervention within cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) since its development at the start of this century (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019). SP/SR is the therapist’s personal process of self-applying cognitive behavioural techniques in conjunction with reflection and appraisal of this experience (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001). It typically involves the use of a manualised workbook (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) and can be delivered via groups, co-therapy pairs or on an individual basis (Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington, Grey and Whittington2014). Originally developed in CBT training, the application of SP/SR has now been expanded to include other psychotherapeutic modalities such as compassion focused therapy (Kolts et al., Reference Kolts, Bell, Bennett-levy and Irons2018) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Tirch et al., Reference Tirch, Silberstein-Tirch, Codd, Brock and Wright2019).

Studies examining outcomes for cognitive behavioural therapists undergoing SP/SR suggest that benefits include increased empathy (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Thwaites, Freeston and Bennett-Levy2015), improved conceptual skills (Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Gibson and Flett2011) and greater confidence (Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). SP/SR outcome studies tend to rely on therapist self-ratings rather than client appraisals of efficacy (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019) but there is evidence from psychotherapy research that increased therapist skill and understanding does lead to improved client outcomes (Sandell et al., Reference Sandell, Carlsson, Schubert, Grant, Lazar and Broberg2006). Another potential advantage of SP/SR is that it may be a form of personal practice which is preferred by trainees themselves (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Bennett-Levy, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2020).

Given the potential benefits of this intervention to both therapists and clients, it is valuable to assess individual differences in therapists’ engagement with the process (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014). A range of both positive and negative experiences have been documented by therapists undertaking SP/SR with some participants reporting distress (Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016) and certain programmes sustaining high attrition rates (Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2015). Similarly adverse effects have been observed in the experiences of other trainees undergoing personal therapy within psychology training (McMahon, Reference McMahon2018) and psychotherapy training more broadly (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018). A model of SP/SR engagement proposed by Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) based on the authors’ qualitative research posits five key influencing factors: course structure and requirements, expectation of benefit, feeling of safety, group process, and available personal resources.

The specific focus of the current study is how CBT therapists experience feeling of safety (FOS) within the process of SP/SR. Within psychotherapy, the establishment of a sense of safety is assumed to be a pre-condition of productive experiential group work for both clients and therapists (Yalom and Leszcz, Reference Yalom and Leszcz2005). Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015b) characterise FOS within SP/SR as an indicator of the effectiveness of structures intended to promote self-exploration, self-reflection and the sharing of reflections with peers. Given precedence as a core requirement for SP/SR engagement, it is prioritised at group initiation (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003).

More universal descriptions of FOS ground the experience of feeling safe in the body. Greenberg (Reference Greenberg1991) defines safety as a sense of physical and emotional wellbeing, free from the pressure of need and anxiety. Polyvagal theory (Geller and Porges, Reference Geller and Porges2014) asserts that one’s sense of safety is predicated on events in the nervous system whereby vagal motor pathways reduce heart rate, inhibit the fight or flight mechanism and ultimately regulate body state.

Attempts to achieve FOS within SP/SR are currently informed by adherence to ethical principles (Schneider and Rees, Reference Schneider and Rees2012) and the experience of programme coordinators (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015b). A deeper understanding of cognitive behavioural therapists’ experience of this influencing factor, as sought in this study, has the potential to improve the implementation and ultimate efficacy of this evidence-based training intervention.

Few studies have investigated engagement factors for SP/SR (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016) and none has targeted FOS specifically as a focus of exploration. The question of how safe therapists feel as they engage with experiential groups has not been extensively investigated within psychotherapeutic research. One reason, posited by Segalla (Reference Segalla2018), for a discernible lack of targeted research on sense of safety in the psychotherapeutic climate may be that, like oxygen, it can be taken for granted. Freeston et al. (Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019) note a lack of data on SP/SR engagement factors and conclude that there are currently insufficient empirical findings for a systematic review of these factors. Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) highlight the desirability of more closely analysing the engagement factors identified in their study, particularly as their data support the notion that engagement and experience of benefit are mutually influential.

Empirical findings relating to FOS within SP/SR tend to be from qualitative research (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015b; Farrand et al., Reference Farrand, Perry and Linsley2010; Spafford and Haarhoff, Reference Spafford and Haarhoff2015) or studies conducted using mixed methods (Schneider and Rees, Reference Schneider and Rees2012; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016).

In Bennett-Levy and Lee’s (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) seminal study on engagement factors, the key constituents in the absence of FOS within the process were identified as fear of personal distress and fear of exposure to others. These sub-themes were endorsed and elaborated in other studies which reported SP/SR participants’ experiences of feeling vulnerable (Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016), feeling uncertain (Schneider and Rees, Reference Schneider and Rees2012) and fear of making disclosures in front of peers (Spafford and Haarhoff, Reference Spafford and Haarhoff2015).

Participants’ experiences of FOS within SP/SR tend to be idiosyncratic (Schneider and Rees, Reference Schneider and Rees2012) and other influencing factors may be cited as more crucial to engagement. Haarhoff et al. (Reference Haarhoff, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2015) found that perception of available time as a personal resource, rather than FOS, was seen as the most important influence on SP/SR engagement. Another significant finding is that experience of FOS is not static and may develop over time (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Wilson, Nelson, Rotumah, Ryan, Budden, Stirling and Beale2015a). A lack of continuous FOS during the process of SP/SR has been found to be desirable as participants are likely to derive benefit from experiencing some level of distress (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003). Farrand et al. (Reference Farrand, Perry and Linsley2010) highlight the fact that participants normalise the struggle to work through CBT interventions as an example of how distress can promote empathy for the client.

FOS was not the primary focus of these largely qualitative studies, but they do reveal recurrent sub-themes relating to experiences of personal distress and fear of exposure. The fact that these sub-themes are not universally endorsed and that other dynamics clearly affect subjective safety within SP/SR suggests that there is further research needed about how SP/SR participants experience FOS. This view is reinforced by an examination of studies within the broader realm of psychotherapy which document participants’ experiences of FOS within experiential groupwork. Such studies not only endorse themes of personal distress and fear of exposure to others (Jakubkaitė and Kočiūnas, Reference Jakubkaitė and Kočiūnas2014; McMahon and Rodillas, Reference McMahon and Rodillas2020; Moller and Rance, Reference Moller and Rance2013; Rees and Maclaine, Reference Rees and Maclaine2016) but identify other potentially important factors such as sense of shared purpose within the group (Robson and Robson, Reference Robson and Robson2008), perception of other participants (Jakubkaitė and Kočiūnas, Reference Jakubkaitė and Kočiūnas2014; Payne, Reference Payne2001) and the physical environment (Robson and Robson, Reference Robson and Robson2008).

In order to assist those responsible for the design and implementation of psychologically safe SP/SR programmes, it seems desirable to obtain a deeper understanding of FOS within SP/SR. To this end a qualitative study, employing interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was conducted with the aim of exploring CBT therapists’ experience of FOS within SP/SR.

Research question

What is the lived experience of FOS within SP/SR as experienced by CBT therapists?

Method

Study design

This study aimed to explore CBT therapists’ experience of feeling of safety (FOS) within SP/SR. Studies suggest that CBT therapists’ experience is mixed, therefore a qualitative approach was adopted for a number of reasons. For example:

-

(1) Qualitative methodologies take a critical stance towards knowledge and recognise the influence of history and culture and appreciate how we construct such knowledge intersubjectively (Langdridge, Reference Langdridge2007).

-

(2) Individuals’ lived experience is better understood through an interpretive and idiographic perspective, thereby bringing understanding to individual experiences, as not all that we wish to explore is observable.

-

(3) By exploring idiographic (unique and individual) interpretations using qualitative research methods, the researcher gains insights into subjective meaning making rather than objectifying the unique relationship between individuals and their world.

-

(4) As it is not possible to objectively measure or quantify experiences, a quantitative approach would have been inappropriate for this study. The particular phenomenon, FOS within SP/SR, was explored as it exists in reality as constructed by the individual (Smith, Reference Smith2008).

A number of methods were considered including thematic analysis, descriptive phenomenology and interpretative approaches. A phenomenological approach was preferred to elucidate experiences of FOS as lived through by individuals in reality (Finlay, Reference Finlay2011). Within the realm of phenomenology, an interpretative rather than descriptive methodology was selected. Descriptive phenomenology is primarily concerned with developing accounts of commonality in experience, so that a complete and integrated eidetic picture of a particular phenomenon can be built up. Hermeneutic (interpretative) approaches such as interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), by contrast, have the idiographic aim of providing a detailed analysis of divergence and convergence across cases, capturing the texture and richness of each individual examined (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). IPA is designed to focus on existential, idiographic elements by unpicking individuals’ meaning-making about their experiences (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). IPA is a phenomenological methodology which aligns more with hermeneutics (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). Thematic analysis on the other hand is the process of identifying patterns or themes within qualitative data and is a method rather than a methodology and is therefore not aligned with a particular epistemological or theoretical perspective (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006).

As the focus of this study was on personal meaning and sense-making (FOS) in a particular context with participants who shared a particular experience (SP/SR), IPA was an appropriate study design. A double hermeneutic was applied as the researcher aimed to make sense of the participant making sense of the phenomenon of FOS (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). IPA combines phenomenology, hermeneutics and idiography. The idiographic focus, whereby the researcher aims to grasp meaning at the level of the particular or individual, is seen as a particular advantage of IPA. Furthermore, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) argue that IPA is an appropriate methodology for a more existentially informed investigation of a smaller, demographically homogenous group. Finally, this methodology has high ecological validity, whereby findings are likely to generalise well to a naturalistic setting (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). In this case the aim was to uncover findings which would be of relevance to the construction and implementation of future SP/SR programmes.

Recruitment process

Following ethical approval, the head of mental health services for the area where the study was conducted was contacted to act as gatekeeper in the process of recruiting participants. Letters of invitation to participate were subsequently disseminated via email by the head of mental health services to employees within this service with information pertaining to the study. Eligible clinicians were those who had completed an SP/SR programme while undertaking CBT training to at least postgraduate diploma level within a university setting. Participants were invited to contact the research team if interested in participating in the study.

Study sample

Purposive sampling was used in this study. A homogeneous sample (n=3) of three CBT therapists who were also mental health nurses responded to the letter of invitation and met the eligibility criteria. All three participants had completed their CBT postgraduate training programme in the same university. All three participants were female, Caucasian and of middle socioeconomic background. This was participants’ first experience of SP/SR. This had the advantage of facilitating a more focused investigation by reducing variation and increasing the potential applicability of findings (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). IPA researchers work with homogeneous samples for a number of reasons (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). It is accepted that generalisations cannot be drawn from the small samples of in-depth qualitative methods, so it can be useful to drill down into specifics. Secondly, it is possible to arrive at more meaningful statements about any psychological variation in the group when using groups with relatively uniform demographics such was the case in this study (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). A small sample size is often favoured within IPA studies as it allows the analysis of rich data which can be processed in highly meaningful ways. The aim is to reveal detailed experiences rather than to establish more general claims (Smith, Reference Smith2008).

Procedure

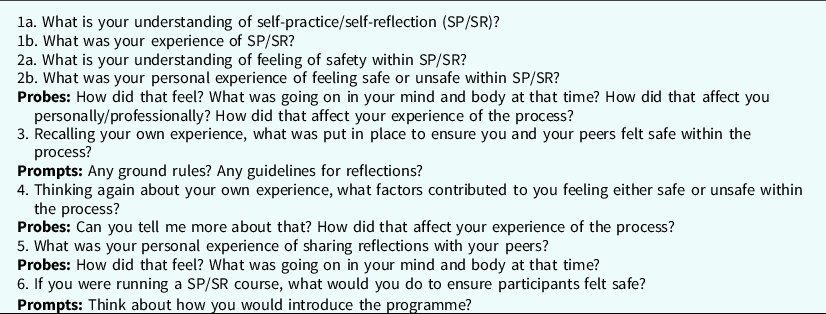

Participants who agreed to be interviewed were contacted by email and a suitable time arranged through subsequent telephone communication. Following consultation with the relevant ethics committee, telephone interviews were approved as an amendment to the originally approved ethical submission. This amendment was necessitated by the conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in restrictions of movement of people directed by government informed by public health advice. Under these restrictions, it was not permitted to meet participants face-to-face. The study employed a semi-structured interview, a data instrument preferred in IPA for its flexibility (Smith, Reference Smith2008). Six broad and open questions (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) were deployed to access participants’ personal experience of safety within SP/SR and their perceptions regarding factors contributing to this phenomenon.

Participants were specifically questioned about their experience of disclosing reflections in front of their peers and how they would ensure FOS if they were running a SP/SR course. Prompts and probes were included to encourage participants to answer questions in more depth (Harvey-Jordan and Long, Reference Harvey-Jordan and Long2001). The interview schedule employed is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Interview schedule

Prior to the interview commencing, written consent was obtained following discussion pertaining to the interview, transcription, use of anonymised quotes and publication. Interviews were transcribed by the researcher (M.M.) and transcriptions filed in a password-protected computer.

Data analysis

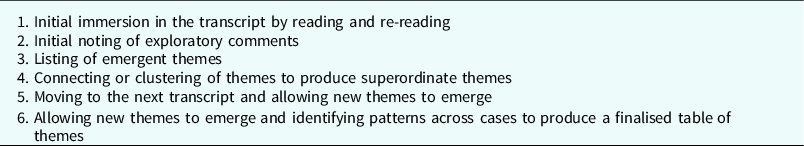

The aim of IPA analysis was to produce a detailed and systematic recording of the themes and issues addressed in the interviews and to link the themes and interviews together under a reasonably exhaustive category system (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). This was achieved using Smith et al.’s (Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) six stages of data analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2. Stages of data analysis

Raw data, in the form of transcriptions from interviews, were processed verbatim in accordance with IPA conventions which promote a semantic understanding and an interpretative relationship with the transcript (Smith, Reference Smith2008).

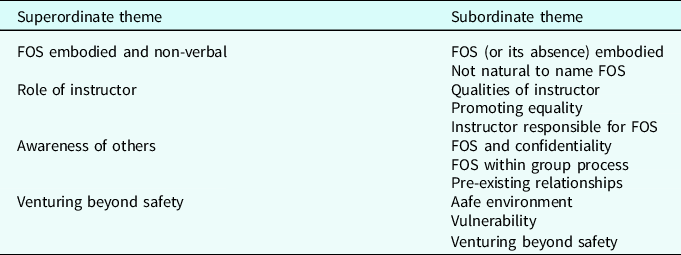

The first author took the lead in the analysis, which was audited by the second author. The first author is a CBT therapist and mental health nurse in clinical practice with a master’s degree in cognitive behavioural psychotherapy. The second author is an academic, CBT therapist and an IPA researcher experienced in conducting research using IPA and supervising students using this methodology. Both authors contributed to writing up and commented on interpretations thereby ensuring rigour. As IPA subscribes to the concept of the double hermeneutic, meaning that the researcher is making sense of the participants’ sense-making, analysis by both researchers had the potential to draw out different elements of participants’ accounts. Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) argue that this joint approach to analysis adds to the credibility of the write-up of findings as it is acknowledged that there can be multiple understandings, which is consistent with IPA research. One researcher was primarily responsible for immersion in the transcript and initial production of linguistic, descriptive and conceptual commentary (steps 1 and 2). The allocation of these exploratory categories was discussed and amended where necessary in collaboration with the co-researcher. For example, this process resulted in the recategorization of some linguistic comments to conceptual comments through a reflective collaboration between both researchers. A similar process of discussion and amendment occurred as emergent themes were identified (step 3) and clustered to produce superordinate themes (step 4). Steps 1 to 4 were applied, with the same collaboration between researchers, for all three participants. New emergent and superordinate themes were allowed to develop for each participant (step 5). A close scrutiny of patterns between the three sets of superordinate themes led to the establishment of master themes for the group (see Table 3). Again, the selection of these ultimate themes was informed by discussion between the researchers. Finally, the original transcripts were re-read to confirm that over-arching themes authentically represented the narratives, and anonymised transcript quotations were linked to each theme.

Table 3. Master table of themes for the group

Quality of research was upheld by implementation of sensitivity to context, commitment and rigour, transparency and coherence and impact and importance. These criteria are established by Yardley (Reference Yardley2000) to underpin high quality qualitative research. Smith’s (2011) IPA evaluation guide was also consulted to confirm acceptability in relation to quality. Peer review, academic supervision, an audit trail and maintenance of a reflexivity journal all contributed to the establishment of trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). The researchers were aware of their own understanding, knowledge, and biases throughout the research process and considered bracketing in addressing this. Martin Heidegger et al.’s (Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson1962) viewpoint regarding bracketing was considered more realistic as it is difficult not to be impacted by one’s own assumptions and beliefs. However, to mitigate against this, reflexivity was utilised to continually monitor and audit the research process. Reflexivity and adopting the phenomenological attitude were utilised to bracket off any pre-suppositions throughout the interview process.

Results

Six superordinate themes emerged from analysis of the data. Four of these relate directly to participants’ experience of FOS: FOS and its absence as embodied and non-verbal, role of instructor, awareness of others and venturing beyond safety (see Table 2). Two additional superordinate themes, time and evolving perspectives and separate space, are beyond the remit of this discussion as they do not directly pertain to participants’ experience of FOS. The four superordinate themes each hold subordinate themes, common to all participants. These superordinate and subordinate themes are described and interpreted below (in both narrative and table form) with pseudonymised exemplar quotations presented in support.

FOS and its absence as embodied and non-verbal

Participants tended to represent FOS and its absence in physical rather than verbal terms. The superordinate theme FOS and its absence as embodied and non-verbal contains two subordinate themes, referred to here as FOS (or its absence) embodied and Not natural to name FOS.

FOS (or its absence) embodied

In various ways, the participants all describe FOS as a bodily experience. Gail relates how she felt while situated within the group and locates safety in her body: Feeling safe, calm… in my body. Um, feeling more settled and, yeah, and comfortable in that situation I suppose, while Lisa highlights the physical experience of feeling unsafe: Feeling unsafe really would be kind of like your natural, um, physical reaction to the unknown. Jan does not explicitly state that she felt safety in her body, but her mention of stress suggests that her experience had a physical component: Something that’s very comforting and very slow… that kind of just takes away the stress a little bit.

Not natural to name FOS

On several occasions the participants seemed to stumble over their verbal attempts to describe FOS. The awkward nature of these descriptions gives the impression of a process which is not natural. Jan illustrated a possible disconnect between an embodied FOS and verbal expression of the experience: I don’t know whether I appreciated it as… as a feeling of safety. It was more a feeling of kind of calmness. Even when Lisa was powerfully aware of her FOS, her awkward phrasing indicated that linguistically naming such an experience was alien to her: After doing the mindfulness I felt very, very kind of safe. Gail described a scenario in which SP/SR participants would feel safe enough to disclose their experience, if they were exposed to typical examples of contributions. Although she readily identified the outward behavioural manifestation of this safety, she did not access the language to describe the underlying feeling: So that people in the class are maybe more forthcoming or - … I’m not quite sure what I’m trying to say. Confirming that FOS was not verbalised during the SP/SR module, Jan asserted: I always felt safe there. But like, it was never something that was ever discussed.

All participants claimed to have felt safe during the SP/SR but it seems this may have been experienced at a non-verbal level.

Role of instructor

In all three participants’ narratives, the role of the instructor in promoting FOS emerged as a superordinate theme. This superordinate theme is represented in subordinate themes identified as Qualities of instructor, Promoting equality and Instructor responsible for FOS.

Qualities of instructor

Participants appreciated different qualities displayed by the instructor, some of which hint at a particular quality of atmosphere within the setting. Gail noted: The module leader at the time just was very easy going. Jan named the particular attributes of the instructor which she found helpful. She again used the concept of comfort to convey safety while highlighting the importance of feeling free of judgement: Gary was very non-judgemental and comforting. So, I suppose I took a lot from that. It did help. Lisa explicitly linked the instructor’s qualities and safety, naming core therapeutic qualities required in any psychotherapeutic endeavour: You automatically kind of felt safe. And it’s all definitely, again reflecting back on my lecturer… he was really genuine, really warm and, he was very um, very empathetic. Within her narrative, she constantly related SP/SR to CBT: Understand your thoughts, feelings and your behaviours in certain situations. It is apt therefore that she associated safety with those necessary core conditions of the therapeutic space.

Promoting equality

Within their accounts of feeling safe, the participants mentioned equality in a manner which suggested it may be relevant to FOS. Lisa illustrated this as she recounted how the instructor was able to give group members equal opportunity to contribute: There was no specific, um, you know, person in the group that was taking over the whole session or anything like that. Like it was really kind of… Felt really safe I think, it was all really kind of on a common level with everyone. Jan used a sporting metaphor to convey the potential skill required to promote equality in this context: It was more Gary’s skill of, again, levelling the playing field I suppose. In extolling the instructor’s ability to promote equality, Gail inadvertently alluded to the natural hierarchy of the lecturer–student dynamic: That was… getting down to our level and validating. There was a recognition here that promoting equality involves contending with the fact that there may be inherent inequality of status, at least between instructor and participants.

Instructor responsible for FOS

The participants seemed in no doubt as to who was responsible for the presence of FOS.

Jan illustrated this unequivocally: The safety aspect rests very much with the leader. Lisa attributed her own FOS to the instructor: The reason why I felt that it was safe was, came down to the lecturer. Gail endorsed the notion of skill being a requirement for the promotion of FOS as she credited the instructor with helping to support her own FOS: I always felt really safe, um, within our group and… our facilitator I suppose was, … um, extremely good at that. The promotion of FOS was portrayed as a proactive process requiring skill on the part of the instructor. It is worth noting in this context that two of the participants cited the instructor’s use of mindfulness within the sessions as instrumental in establishing FOS.

Two participants also highlighted the fact that the instructor arranged the seats in a circle as fundamental to equality and associated FOS.

Awareness of others

The participants all expressed an awareness of others in relation to FOS within SP/SR. Awareness of others forms a superordinate theme consisting of the subordinate themes FOS and confidentiality, FOS within the group process and Pre-existing relationships.

FOS and confidentiality

All participants placed strong emphasis on the need for confidentiality to be upheld.

Gail’s understanding of FOS is rooted in this requirement: I suppose my understanding of feeling safety is within the group that it’s confidential and, you know, that that’s not taken outside of the group. Lisa offered her own perspective on confidentiality: Well I suppose, um, confidentiality is just, it’s it’s so important really. Jan indicated that the thought of a breach in confidentiality is enough to compromise FOS: There was a fear that maybe it might… be remembered on Tuesday morning or even discussed. Fear of judgement was not explicitly mentioned by all participants, but may relate to confidentiality. Talking about how confidentiality was upheld, Lisa related this to being free from judgement, which in turn she associated with FOS: It was really kind of a non-judgemental feel. So I did find that that was extremely safe. The need for confidentiality was constantly expressed throughout the participants’ discussion of FOS.

FOS within the group process

Beyond the minimum standard of confidentiality being upheld, participants found trust and support in the group process. Gail referred to a process whereby apprehensions about making contributions were normalised within a supportive group: Um, validating probably again that actually, yeah, others have experienced that or, you know, um and encouraging and I suppose sense of support from colleagues. Lisa reported: I suppose people are trusting you to listen… and I think that all gives back kind of safety. A sense of FOS emerging within the group was suggested in Jan’s account: The other thing that made it less uncomfortable was listening to everyone else. The participants represented their experience of group process as generally supportive and conducive to FOS.

Pre-existing relationships

For all participants, this experience was shared with, at least some, work colleagues. Gail saw the pre-existing relationship in this context as benefiting FOS: We all knew each other quite well in the class as well, um which did aid us in, in a way, whereas Jan felt FOS would be improved by avoiding an overlap of roles within the group: I would try and make sure that people that have a lot to do with each other outside of this, not be in the same group. Pre-existing safety may not be immutable. Lisa captured the potentially equivocal nature of the relationship between FOS and pre-existing bonds: I was quite friendly with them as well. So I did feel that safety there with them. However at the same time I suppose the unsafetyness about it is… kind of your opening up to people that you, that are your work colleagues. With this level of familiarity, it was all too easy for her to imagine a breach of confidentiality: Is that person going to go back to, um, her close friend and say that about me? The participants consistently conveyed that their experience of FOS was affected by the presence and behaviour of the other group members.

Venturing beyond safety

The final superordinate theme which emerged was venturing beyond safety. It was apparent from participants’ accounts that although there was a baseline experience of safety, some of the SP/SR process involved a departure from feeling secure. The subordinate themes contained here were Safe environment, Vulnerability and Venturing beyond safety.

Safe environment

Gail acknowledged her own FOS within the environment succinctly: I always felt really safe, um, within our group. Similarly, Lisa reported: It was just more of a safe environment. Jan emphatically asserted an SP/SR experience, which she distinguished as her own, that was free from unsafety: There was never unsafety. That definitely …wasn’t a present for me anyway. Unless there was for others, but it definitely wasn’t for me.

Vulnerability

Although the participants all characterise their overall experience of SP/SR as highly safe, they also acknowledge feeling vulnerable at times during the module. Jan spoke for the group on this point and indicated that vulnerability may relate to a sense of exposure: This module showed a vulne… vulnerable side to us and that this stuff could be seen by other people.

Gail related the insecurity she experienced in moments of self-disclosure: It probably makes you a little bit more conscious, you know, that you’re like, ‘Oh God, is this the right thing to be saying’. Lisa graphically depicted the risk of being psychologically wounded in this process: When you are really opening up and being quite vulnerable about your specific situation. Despite their assertions of feeling safe within the process of SP/SR, participants conveyed a strong sense of vulnerability.

Venturing beyond safety

The accounts of the participants suggested that, however consciously, they must venture beyond their safe baselines in order to engage meaningfully in the group process. Gail alluded to the courage which this requires: It always felt like a space where we were encouraged, to…, um to contribute. Jan captured the tension between safety and self-disclosure as she discussed the use of the journals the participants kept within her own SP/SR group: It was your issue and your journal. Do you know, so there was that kind of, I don’t know, I suppose privacy in a way. And yet you felt you could disclose. Perhaps the apparent contradiction was best reconciled by Lisa: I think it all stems from that safety behaviour. I think that everyone did really feel quite safe… and as the sessions went on as well, people were more inclined to really open up about their situation. Here, she is narrating how group members became increasingly confident in their contributions. Her use of stems, with its connotation of growth, reveals how the anxiety-provoking behaviour of self-disclosure was rooted in FOS. Lisa described a scenario where the confidence of participants’ to disclose gained momentum as the group work progressed: And I do think that everyone became kind of more relaxed then and more safe to speak of their, whatever issues may be occurring.

The phrase safe to speak perhaps encapsulates how a safe base permitted the participants to become venturesome.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore CBT therapists’ experience of FOS in SP/SR. Four key themes emerged, including FOS embodied and non-verbal, role of instructor, awareness of others and venturing beyond safety. The finding that participants experienced FOS at an embodied level endorses previous theoretical descriptions of safety (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1991).

Participants’ implicit references to the nervous system can be understood within cognitive science frameworks used to underpin the theoretical basis of SP/SR (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Wilson, Nelson, Rotumah, Ryan, Budden, Stirling and Beale2015a). A seminal SP/SR workbook (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015b) recognises the close relationship between the body and emotion and highlights the implicational system of Teasdale and Barnard’s Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (Barnard, Reference Barnard2004). The implicational system refers to implicit information-processing derived from the body, emotions and sensory information. The implicational system is contrasted with the propositional system which is explicit and contains knowledge which can be tested (Barnard, Reference Barnard2004). The participants’ accounts of FOS often seem to reflect an implicit, bodily processing of experience.

Traditional cognitive theories of information-processing include the three systems model of fear and emotion (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Levin, Miller and Kozak1983). The theory posits that emotional responses occur within three partly independent systems of experience, namely verbal, gross motor and physiological. The physiological system, which may be implicated in this study’s theme of FOS and its absence as embodied and non-verbal, includes autonomic, cortical and neuro-muscular functions.

A more contemporary perspective on FOS, which also names the autonomic system, is offered by polyvagal theorists (Geller and Porges, Reference Geller and Porges2014). Exact accounts of how vagal pathways operate to assess safety remain at the level of a theory or perspective (Flores and Porges, Reference Flores and Porges2017). Polyvagal understandings, however, draw on the established work of attachment theorists (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby2005) who also note that safety is detected in the nervous system using unconscious perception of social cues. It is notable that participants are more able to represent their embodied experiences of FOS verbally when safety is absent.

An interpretative reading of participants’ inability to verbalise FOS suggests that it is because of the deeply embodied nature of the experience that participants are unable to access it readily at a linguistic level. Embodied experiences are known to be strongly felt but hard to communicate or verbalise (Bosman et al., Reference Bosman, Spronk and Kuipers2019). FOS may be an example of a phenomenon which is encoded pre-verbally. Young et al. (Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003), developing a framework for schema therapy, assert that early adverse relational experiences contribute to the formation of maladaptive schemas. One domain in which this can occur is secure attachment. Such formative experiences may not be explicitly remembered (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003).

Husserl (Reference Husserl2014), the father of phenomenology, coined the term empfindnisse to distinguish sensations felt in our bodily depths from those on the surface. For experiences such as FOS, the category of embodied action is expanded to include being affected rather than acting. The fact that new language was required indicates that Husserl was struggling to articulate something not captured in ordinary language (Moran and Cohen, Reference Moran and Cohen2012). It is worth cautioning that rather than supporting any particular model of emotional processing, difficulty in verbalising embodied states may merely point to the limitations of language in relation to certain phenomena (Panhofer and Payne, Reference Panhofer and Payne2011).

Bennett-Levy and Lee’s (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) seminal study on SP/SR engagement factors addresses the theme of FOS by referring to its absence, but there is no attempt to represent how a positive sense of safety might be experienced by participants. The fact that themes in this study emerged following grounded analysis suggests that this omission likely reflects deficits in the participants’ own accounts regarding FOS.

In the same study (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) the role of the instructor is described as a ‘hidden presence’. The current study identified a specific theme of the role of the instructor as an explicitly stated influencing factor for the participants’ FOS. Participants seem clear that the instructor has ultimate responsibility for FOS. In addition to benefit reported from the instructor’s core therapeutic qualities (Yalom and Leszcz, Reference Yalom and Leszcz2005), participants cite the importance of his creating a ‘level playing field’. One consideration here is the physical layout of the group. A circle is traditionally viewed as promoting equality, as all members can be seen and no member is physically represented as superior through placement at the ‘head of the table’ (Karampoula and Panhofer, Reference Karampoula and Panhofer2018). This may be a point of negotiation, however, as leading researchers of SP/SR advocate collaboration between facilitator and participants (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). However, the seating is configured, and the instructor may need the skills and qualities identified in the participants’ data to diminish any unintended effects of the innate status difference between facilitator and instructor (Anderson and Price, Reference Anderson and Price2001).

Another way in which the instructor may proactively imbue SP/SR sessions with FOS is through the use of mindfulness. Gloster-Smith (Reference Gloster-Smith2004) observed that a successful group work facilitator needs to access his or her inner space of calm in order to remain present. Deployment of grounding techniques such as mindfulness, at a group level, may well serve to spread this feeling of calmness throughout the group.

In the model of engagement factors proposed by Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), group process is proposed as a key influencing factor for SP/SR engagement. The current study highlights the importance of various aspects of this factor in relation to FOS. Participants’ concerns over confidentiality (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) are strongly endorsed, as is the development of a supportive learning environment (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). The finding that participating in SP/SR with work colleagues may inhibit engagement (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) is endorsed by the current study which also recognises that these pre-existing relationships can foster FOS.

It is important to acknowledge that all participants in this study reported an overall presence of FOS in their SP/SR experience. It is apparent, however, that going beyond safety is a necessary part of this intervention. The vulnerability inherent in this is noted in previous SP/SR research (Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). A significant function of the SP/SR engagement model produced by Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) was to guide the set-up and development of SP/SR programmes. The module stipulates FOS as one of five influencing factors for engagement along with course structure and requirements, expectation of benefit, group process and available resources. The current study supports these findings. Participants notably mention elements of course structure and group process in relation to FOS.

Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) found fear of personal distress and fear of exposure to others to be the primary causes of diminished FOS. Fear of distress was not endorsed thematically in the current study and group process emerged as potentially increasing or decreasing FOS depending on the interpersonal dynamic under consideration. An obvious threat to FOS, predicted by Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) and confirmed by the current study, was potential for a breach of confidentiality.

Implications for theory and practice

The original aim of this study was to explore CBT therapists’ experience of FOS within SP/SR and identify factors which influence this experience. The findings pertaining to these questions hold implications for theory and practice. Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) highlight the instructor’s role in monitoring the wellbeing of participants. The finding in this study that FOS is predominantly an embodied, non-verbal phenomenon indicates that monitoring should entail high awareness of physical cues. The instructor must attend to the social context of these cues as participants appear to be highly attuned to the responses of other group members. His or her own active participation in this exchange should be borne in mind.

Although participants may not spontaneously verbalise their FOS, the results from this study indicate that they are often very conscious of being in a vulnerable situation (Spendelow and Butler Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Wilson, Nelson, Rotumah, Ryan, Budden, Stirling and Beale2015a) refer to a duty of care in relation to facilitators’ having awareness of the effect the process is having on participants. This may involve attending both to what participants verbalise and to their non-verbal communication. It is hypothesised that the nervous system evaluates risk without conscious awareness. Consideration of this process, referred to as neuroception by polyvagal theorists (Flores and Porges, Reference Flores and Porges2017), may provide a useful tool for instructors monitoring their participants’ wellbeing. Within this theory, mutually arising safety is clearly evidenced in spontaneous social behaviours in areas such as prosody and eye contact.

In order to fulfil the proactive role in FOS expected of the instructor, implementation of interventions which directly promote FOS at a physical level should be considered. Examples of such interventions may include mindfulness exercises like the body scan meditation (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn2013) and the soothing rhythm breathing practised in compassion focused therapy (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010).

Having the entire group engaged in the same activity, with the same purpose, may also help to promote a sense of equality, which the current study found to influence FOS. The equivocal nature of FOS with respect to pre-existing relationships must be considered by course administrators and instructors. The latter should be aware that FOS may fluctuate in this regard. Throughout the process the instructor should maintain an encouraging stance, mindful of the bravery required of participants to overcome the insecurity and uncertainty inherent in self-disclosure. The concept of encouragement is underexplored in psychotherapy (Wong, Reference Wong2015) but this function of the instructor manifests the supportive role advocated by seminal proponents of SP/SR (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Wilson, Nelson, Rotumah, Ryan, Budden, Stirling and Beale2015a).

Strengths and limitations

This study gains strength from a consistent focus on the lived experience of the phenomenon under focus. Methodologically, significant collaboration on data analysis between researchers enhances the trustworthiness of the research. Smith’s (2011) IPA Evaluation Guide (see Supplementary material) was used to ensure that standards of good IPA research were achieved. One benefit of adherence to this guide is that every theme presented here is represented by extracts from all three participants as recommended for this sample size (Smith, Reference Smith2011).

Limitations of the study may pertain to transferability (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). Findings may be applied to other SP/SR courses in the knowledge that data emerged from the narratives of three female participants, all of whom were employed as mental health nurses. Potentially mitigating this limitation is that FOS, stripped of its context, is a universal mammalian phenomenon (Flores and Porges, Reference Flores and Porges2017).

For any study with a retrospective component, the limitations of memory must be acknowledged. Beckett et al. (Reference Beckett, Vanzo, Sastry, Panis and Peterson2001) assert that retrieval can be impeded in one of three ways: failure to process or encode in the first place, retrieval failure as a consequence of the memory never being rehearsed, and inaccurate reconstruction. For the current study it is impossible to assess the effect of initial non-processing or inaccurate reconstruction but there may be evidence against the notion that SP/SR memories were not rehearsed. All participants conveyed a strong sense that the utility of the module endured for them and two explicitly stated that they periodically consult the SP/SR manual utilised during the course. It is worth noting that participants’ verbal recollections may not represent the entirety of their remembered experience of FOS within SP/SR, as embodied emotional states may persist long after they are experienced (Tiba, Reference Tiba2018).

Areas for further research

If further research is to be focused directly onto FOS within SP/SR, it would be desirable to ascertain which factors influence this phenomenon. The data from this study suggest that other factors previously cited as engagement factors, such as group process (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), may affect FOS. Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014) advocate empirical testing of their model of SP/SR engagement factors. With specific focus on FOS, the current study would suggest that further exploration be given to the relationship between FOS and pre-existing relationships within the group. Further studies might enlist participants from other professional backgrounds to explore if FOS themes vary between professions. Given that the application of SP/SR has expanded to other modalities such as compassion focused therapy (Kolts et al., Reference Kolts, Bell, Bennett-levy and Irons2018) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Tirch et al., Reference Tirch, Silberstein-Tirch, Codd, Brock and Wright2019), it would be desirable to investigate the transferability of current findings to other psychotherapeutic modalities where the intervention is employed.

Introducing a quantitative component to research on FOS might augment qualitatively derived findings. Use of a safety scale (McMahon and Rodillas, Reference McMahon and Rodillas2020) throughout the duration of a SP/SR module might valuably enhance knowledge of how this fundamental engagement factor is experienced. The 8-item safety subscale incorporated into McMahon and Rodillas’ Review of Personal Development Group (R-PDG) may prove a useful starting point for the establishment of a safety scale relevant to SP/SR as it explicitly addresses issues such as confidentiality, role of the facilitator and vulnerability (McMahon and Rodillas, 2018).

Regarding the use of interventions which directly target FOS at an embodied level, a review of techniques already in use by SP/SR instructors would help inform research on the efficacy of these measures. As there is a paucity of research on how SP/SR participants experience the module, it is worthwhile for researchers to learn from other disciplines. Bennett-Levy and Lee (Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), for example, reference work within dance movement therapy (Payne, Reference Payne2001) in relation to the pre-requisite status of a safe space for exploration. The emphasis on embodiment of experience within this type of therapy (Karampoula and Panhofer, Reference Karampoula and Panhofer2018) may provide insights to researchers of SP/SR. A universal phenomenon such as FOS (Maslow, Reference Maslow1999) may warrant a particularly open-minded approach.

Conclusion

This interpretative phenomenological analysis of CBT therapists’ experience of FOS within SP/SR has the potential to develop understanding of engagement factors for this training intervention. One general finding was that FOS is influenced by many factors, which may include other previously cited aspects such as course structure and group process.

Overall, participants’ experience of FOS was positive, but a notable feature of the qualitative data was an impoverished linguistic representation of the phenomenon. This is hypothesised to be a consequence of the deeply embodied nature of the experience and means of focusing on physical aspects of FOS are suggested. In tandem with this physical emphasis, a shift from focusing on the absence of FOS to how FOS can be proactively engendered is recommended. An evolving awareness of physical cues between participants, including facilitator, may potentially advance the implementation of FOS within SP/SR groups.

The emergence of data novel to the extant literature on FOS within SP/SR offers further implications for practice. These include the desirability of module components and structures which promote equality and direct impact on FOS at an embodied level. The effect of pre-existing relationships between group members merits further research as findings in this regard are mixed. The bravery required by participants to venture beyond their comfort zone in SP/SR necessitates that instructors consider how they cultivate an encouraging stance.

The interpretative lens of this project allowed theoretical conclusions to be made which may serve to guide further investigation of this universal phenomenon within the specialised context of SP/SR training for CBT therapists.

Key practice points

-

(1) FOS within SP/SR is experienced at an embodied level not readily accessible to language.

-

(2) SP/SR instructors can proactively enhance FOS through the use of interventions which directly affect the body and by the implementation of course components and structures designed to promote a sense of equality.

-

(3) Awareness of physical cues can assist in the monitoring of participants’ wellbeing and engagement.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the cooperation and support of Cork mental health services. We also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the participants who were interviewed for this study.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was granted by Social Research Ethics Committee, reference number 2020-024.

Data availability

The authors have elected not to provide a data availability statement.

Author Contributions

Murray Mackenzie: Conceptualization (equal), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), funding acquisition (equal), investigation (lead), methodology (supporting), project administration (lead), resources (equal), software (equal), supervision (supporting), validation (equal), visualization (equal), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (equal);

James O’Mahony: Conceptualization (equal), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), funding acquisition (equal), investigation (supporting), methodology (lead), project administration (supporting), resources (equal), software (equal), supervision (lead), validation (equal), visualization (equal), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000283

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.