For decades, political scientists have devoted extensive attention to analyzing policy variation across the American states. This line of research has identified numerous political, economic, and social factors that explain why state governments have embraced divergent solutions to a variety of social problems, and it has greatly illuminated the diffusion process through which new policy ideas spread from one jurisdiction to another. With its emphasis on adopted or enacted programs, however, existing research overlooks a substantial proportion of the activity on state legislative agendas. During the 2017 legislative session, for example, state legislators introduced approximately 120,000 bills, and fewer than 20,000 of them gained enactment. Similarly, state legislatures passed only slightly more than 4,500 of the more than 13,000 resolutions that lawmakers introduced that year.Footnote 1

The thousands of proposals that do not successfully navigate the legislative process each year are rarely analyzed in state politics research, and this represents a missed opportunity to enhance our understanding of legislator behavior and state policy and politics more generally. To be sure, scholars have not ignored the discrepancy between the large number of bill introductions and the much smaller number of adoptions that occur. Perhaps most famously, Alan Rosenthal and Rod Forth (Rosenthal and Forth Reference Rosenthal and Forth1978) used variation in state-level “production rates” in their seminal assessment of the legislative “assembly line.” This paper, however, has a slightly different focus. It asks why some bills and resolutions clear more legislative hurdles than others in order to identify the bill-level and state-level characteristics that influence the progress that a given piece of legislation makes.

More specifically, its analytical framework posits that legislative content systematically affects the likelihood that a bill or resolution will advance through the various steps of the policy process. In other words, the specific content of a proposal shapes its likelihood of success, even after accounting for conventional factors like bill sponsor characteristics and chamber rules. This approach responds to recent calls by legislative scholars to examine whether and how proposals’ content affects the policy process (Boushey Reference Boushey2010, Reference Boushey2016; Lapinski Reference Lapinski2013; Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2009). Whereas previous treatments of legislative content tend to place individual policies into very broad categories (e.g., morality policies, regulatory policies, and governance policies) based on the specific substantive issue areas they address, this paper proposes and implements a novel approach grounded in a close reading of individual bills and resolutions. This novel approach facilitates an analysis of the potential relationship between specific provisions of a proposal and its legislative progress, making it possible to investigate why some bills pass and others fail even when they address the same general issue.

Substantively, this paper focuses on a topic—federalism and intergovernmental relations—that cuts across issue domains and has played a key role in the politics and evolution of the American political system (Robertson Reference Robertson2012). Its empirical analysis centers on an original dataset of more than 5,000 proposals that were introduced in state legislatures from 2009 to 2016. These bills and resolutions address policy areas that span the ideological spectrum. The analysis begins by comparing proposals that challenge the authority of the national government to proposals that lack federalism-related implications, classifying the former based on the specific nature of the challenge they pose. It finds that, all else being equal, proposals with federalism-related implications clear fewer legislative hurdles toward enactment. The analysis then compares the federalism-related proposals to one another, finding that more aggressive challenges, all else being equal, make significantly less progress toward enactment than more modest forms of state-level resistance. While these findings may not be surprising given the conventional wisdom that the American political system favors incremental rather than radical change (Immergut Reference Immergut, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992; Steinmo and Watts Reference Steinmo and Watts1995; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995), they nevertheless are revealing. State officials can push back against national policies with which they disagree, which several scholars have identified as a desirable feature of federalism in the United States (Bednar Reference Bednar2008; Nugent Reference Nugent2009). As they exploit this prerogative, they are more likely to succeed when their goals are modest.

Legislative Content and the Policy Process

Several strands of research in political science suggest that key components of legislative behavior, such as bill sponsorship and voting patterns, depend on the specific issue being addressed. Consider, for example, the expansive literature on the activities of female legislators, much of which emphasizes the distinct dynamics surrounding “women’s issues” like abortion, sex discrimination, domestic violence, healthcare, education, child care, and other topics (Cammisa and Reingold Reference Cammisa and Reingold2004; Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Swers Reference Swers2002). Similarly, a foundational assumption of the scholarly literature on “morality policy” is that certain subjects provoke political clashes over values and principles that are not amenable to compromise; these subjects are distinguished by their technical simplicity and unusually high levels of public interest and citizen participation (Mooney Reference Mooney1999). Even though the theoretical emphases of these research traditions vary greatly, they operate under the shared assumption that the dynamics of the policy process depend on the specific issue being addressed. In other words, the politics of criminal justice differ from the politics of education, which differ from the politics of healthcare, and so on.

Policy content plays an especially important role in recent scholarship on the diffusion of innovations among the American states. Early studies in this tradition largely ignored differences in policy content and thereby failed to address “an important aspect of variation across time and space that has both theoretical and practical implications” (Karch Reference Karch2007, 69). Numerous diffusion scholars have attempted to address this oversight, positing that the subject matter addressed by a policy innovation affects the speed and extent of its spread (Boushey Reference Boushey2010; Mallinson Reference Mallinson2016; Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2009). For example, recent investigations of diffusion “networks” or “pathways” have speculated about the existence of “policy-specific diffusion networks connecting the states” and hypothesized that the structure of these networks differs across policy types (Desmarais, Harden, and Boehmke Reference Desmarais, Harden and Boehmke2015, 405). Similarly, multiple studies find that complex innovations diffuse more slowly than less technical policies, typically identifying policies as complex or noncomplex based largely on the general issue at stake (Mallinson Reference Mallinson2016; Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2009).Footnote 2 This broad categorization scheme epitomizes a fairly common approach that attempts to capture issue-specific variability.

The issue-based approach described in the preceding paragraphs has produced numerous insights about the policy process. Studies in this research tradition convincingly demonstrate that shifts from one type of issue to another “shape voting blocs and political coalitions” and generate “different party and constituency pressures” (Katznelson and Lapinski Reference Katznelson, Lapinski, Adler and Lapinski2006, 97). In addition, the intellectual foundation of the issue-based approach is “the assumption that policies determine politics” (Lowi Reference Lowi1972, 299, emphasis in original), which is now widely accepted and challenges the emphasis on aggregation that is common in studies of legislative behavior. Still, issue-based typologies suffer from their own set of limitations. Critics assert that they are neither testable nor predictive, that they are overly simplistic, that the different categories may not be mutually exclusive, and that they can neither provide causal explanation nor account for the dynamism of the policy process (Smith and Larimer Reference Smith and Larimer2009, 44). Even some adherents of the typology approach acknowledge that it suffers from the “pitfalls of overaggregation, the absence of a motivating and orienting theoretical compass, and a dependence on time-bound policy categories” (Katznelson and Lapinski Reference Katznelson, Lapinski, Adler and Lapinski2006, 103).

The “pitfalls of overaggregation” are especially problematic for studies, like this one, that attempt to identify the bill-level and state-level characteristics that systematically influence the progress that a given piece of legislation makes. Bills and resolutions addressing the same issue will not necessarily meet the same fate. Some healthcare proposals gain enactment, others clear fewer procedural hurdles, and some receive virtually no legislative attention after their introduction. Aggregating legislation based on subject matter therefore offers limited analytical leverage on these divergent outcomes. As a result, the empirical analysis that follows focuses on “legislative content,” defined here as the specific language and provisions embedded in bills and resolutions. It uses close readings of proposed legislation to identify how proposals differ in both their general goals and specific details. This bill-level approach makes it possible to compare proposals on the same issue to each other, assessing whether differences in their objectives or language explain differences in their legislative success. Rather than comparing bills on healthcare policy to bills on criminal justice policy, for instance, the focus here is on whether the precise language used in a healthcare bill explains why it made more progress toward enactment than a different healthcare bill that lacked similar provisions.

The bill-level approach outlined in the previous paragraph builds on previous research suggesting that the precise content of a proposal affects the policy process. Even seemingly minor differences of this sort can influence the mobilization of specific constituencies, as occurred when state officials debated the creation of lotteries during the 1990s (Pierce and Miller Reference Pierce and Miller1999). Similarly, recent research on criminal justice policy-making attributes differences in legislative outcomes to attributes of the specific policy being considered, including its target population, salience, relative advantage over the status quo, and technical complexity (Boushey Reference Boushey2016; Makse and Volden Reference Makse and Volden2011). This paper extends these observations by positing that differences in the specific language used in a bill or resolution affect the number of hurdles it clears in the policy process. It also introduces the novel approach of focusing on a theme—federalism and intergovernmental relations—that cuts across multiple issue areas rather than on several different policies that address the same general topic.

Policy typologies have been applied in a variety of legislative settings, and the preceding observations about the potential influence of legislative language also possess wide applicability. However, state legislatures are an especially favorable venue in which to investigate the potential impact of bill content. The states represent fifty distinct political environments at any moment in time, offering variability in partisan alignments, economic conditions, chamber rules, and other factors that might affect legislative outcomes. As a result, state-level analyses provide especially strong tests of the hypothesis that the specific language of a proposal influences its likelihood of success. If a state-level analysis demonstrates that bill content affects legislative outcomes even when various environmental factors are accounted for, it will suggest that close readings of bill text should be front and center in future studies of the policy process.

Federalism as a Cross-Cutting Theme

Many important debates in American politics cut across multiple issue areas, and the substantive focus of this paper—federalism and intergovernmental relations—is a good example. The United States Constitution created what James Madison called a “compound republic” with shared policy-making authority across different levels of government (Derthick Reference Derthick2001). Without a clear division of responsibility between the national government and the states (Robertson Reference Robertson2012), the policy boundaries of American federalism are extraordinarily fluid and subject to constant debate and renegotiation. State officials frequently contend that the national government has overstepped its constitutional limits, and these intergovernmental disputes date back to the earliest years of the Republic. In recent years, they have affected many of the central disputes in American politics. Political battles over education, the environment, immigration, and health policy have been, in part, about the proper distribution of authority across the two levels of American government.Footnote 3

In fact, some observers contend that the current era is characterized by unusually high levels of tension between the national government and the states. At a time of intense partisan polarization, state governments have refused to accept or apply for intergovernmental grants that support abstinence-only instruction, high-speed rail, and various other national priorities (Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2012). They have launched lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of national policies like the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Clean Power Plan. In addition to reacting to national policies, state governments have also engaged in “defiant innovation” whereby they “pass laws that not only circumvent, but also reimagine federal law” (Hannah and Mallinson Reference Hannah and Mallinson2018, 403). These and other developments led Gamkhar and Pickerill (Reference Gamkhar and Pickerill2012) to identify the recent emergence of a “fend for yourself and activist form of bottom-up federalism” in which states offer heightened resistance to all sorts of national initiatives.

As the preceding examples demonstrate, state officials can use various tools to contest national policies (Merriman Reference Merriman2019; Nugent Reference Nugent2009). This paper focuses specifically on legislative challenges, which have been legion in recent years. Although its legislative emphasis cannot provide a comprehensive portrait of contemporary state resistance, it provides an analytical opportunity to examine the potential relationship between legislative content and legislative outcomes. Are bills and resolutions with federalism-related content more or less likely to clear various hurdles than legislation that does not engage with issues of intergovernmental relations? Moreover, it is possible to extend this analysis of legislative content by comparing the federalism-related proposals to one another. Close readings of their text can be used to identify critical differences in the nature of the challenge they pose to the national government. Does this variation affect legislative outcomes? Do more aggressive challenges experience more or less success? Contemporary disputes over federalism are so ubiquitous and cut across so many substantive issue areas that they provide the necessary empirical foundation to begin to answer these questions.

Classifying State Challenges to National Policies

This section describes the construction and coding of a dataset that will be used to assess whether legislative content systematically influences the amount of progress that a bill or resolution makes toward enactment.Footnote 4 The dataset extends that of Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018), in which the authors built on the work of the Tenth Amendment Center (TAC) to identify state legislative challenges to national policies. The TAC tracks resistance to the national government across 12 issue areas that span the ideological spectrum, ranging from the ACA and Common Core to license plate tracking and police militarization.Footnote 5 Using an online database, Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) devised deliberately broad search strings to identify bills and resolutions on those 12 issues. The search strings returned 11,649 pieces of legislation that were introduced from 2009 to 2016.Footnote 6 The authors read each proposal and determined that 2,582 of them represented a state-level challenge to national policy. Since this paper focuses on the potential impact of legislative content, it is imperative to compare these “resistance” bills to other legislation. Thus, the empirical analysis that follows supplements the Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) resistance dataset with a randomly selected subset of the 9,067 proposals that were identified with the same issue-specific search strings but not included in the 2018 study because they lacked federalism-related content. Our final dataset includes the 2,582 proposals that represent state-level resistance to national policies and 2,600 proposals that address unrelated concerns like budgeting, manufactured housing, behavioral health services, and employment practices. This expanded dataset permits a systematic comparison of legislation challenging national policies to bills and resolutions that lack resistance-related content.Footnote 7

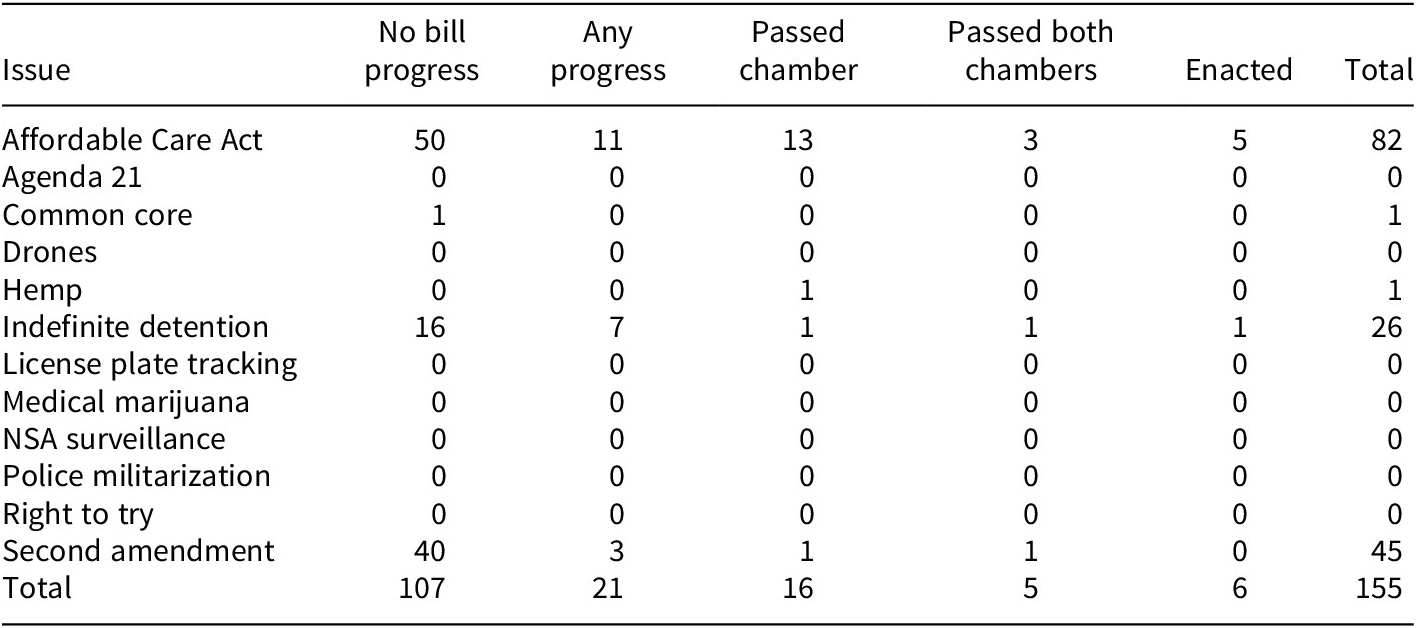

The second step of the empirical analysis extends this interest in legislative content by distinguishing among the resistance-related legislation and comparing these bills and resolutions to one another. Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) put each of their 2,582 proposals into one of three categories based on their federalism-related implications, and this paper utilizes the same classification scheme to account for legislative content. The first category consists of legislation that declares a national policy “null and void” within the state or that explicitly questions its constitutionality. Bills and resolutions in this first category represent the most aggressive form of state government resistance and receive the label of “true” or “pure” nullification. Their language resonates with famous historical documents like the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of December 1828, which challenged the national government’s ability to impose tariffs. For example, the “Second Amendment Preservation Act,” introduced in Minnesota in 2015, declared that “all federal acts, laws, order, rules, or regulations regarding personal firearms, firearm accessories, and ammunition are a violation of the Second Amendment” and “shall be considered null and void and of no effect in the state.”Footnote 8 These types of proclamations are actually quite rare (Dinan Reference Dinan2011; Read and Allen Reference Read and Allen2012). Of the 2,582 proposals in the Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) dataset, only 155 (6.0%) qualify as true or pure nullification.Footnote 9

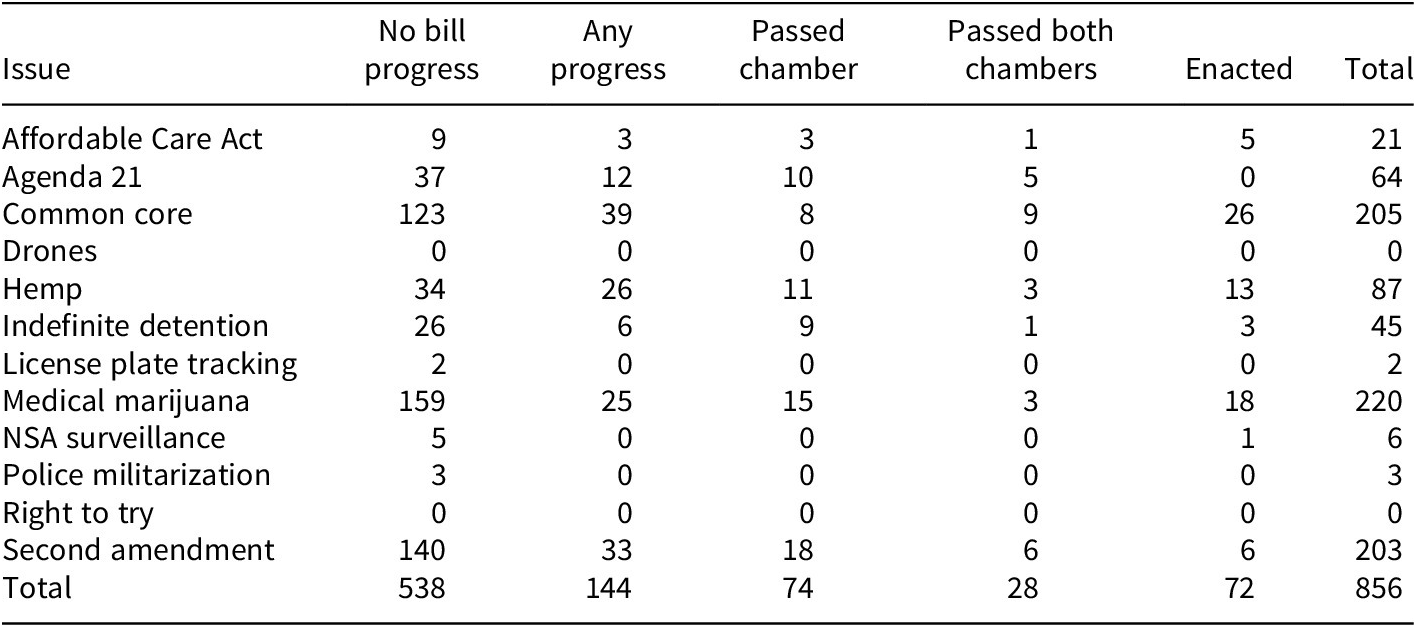

The second category consists of legislation that does not question whether a national law is constitutional but nevertheless pledges that the state will not abide by it. In the words of John Dinan (Reference Dinan2011), these proposals represent “nonacquiescence.” A Texas resolution on the individual mandate imposed by the ACA, for example, proclaims that a “state agency, public official, employee, or political subdivision of this state may not act to impose, collect, enforce, or effectuate a penalty or sanction.”Footnote 10 It pledges not to cooperate with the relevant national law but does not declare it invalid. Many “right to try” proposals are also examples of nonacquiescence. They allow terminally ill patients to use pharmaceuticals that the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved for public use but implicitly recognize the authority of the national government to regulate prescription drugs because they are limited to products that completed phase one of a clinical trial. Nearly one-third of the proposals in the Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) dataset (33.1%) fall into the nonacquiescence category.

The third and final category includes proposals that are inconsistent with national law or a specific legal framework. Of the bills considered here, those in this category represent the mildest form of state-level resistance. Many of them are procedural in nature. For example, a 2015 Massachusetts proposal addresses the topic of police militarization. It does not question the constitutionality of the national program. Instead, it alters the program procedurally by placing it under the jurisdiction of a different state official, calling for the Secretary of Public Safety and Security to approve applications for military-grade weaponry by state police, regional law enforcement councils, and multi-jurisdiction agencies.Footnote 11 Many bills related to drones also fall into the procedural category. They often require a search warrant or “exigent circumstances” for law enforcement agencies to use drones. All the bills in this category, regardless of their substantive content, propose a state policy that is at least partly inconsistent with national policy. However, they work within the existing legal framework and do not declare it invalid. A majority of the 2,582 proposals in the Olson, Callaghan, and Karch (Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018) dataset (1,571 or 60.8%) belong to the procedural category.

In sum, the recent proliferation of state legislative efforts to challenge national policies represents an opportunity to learn more about the dynamics of contemporary intergovernmental relations in the United States. The scholarly literature on the political safeguards of federalism explains how state-level efforts to push back against perceived national government overreach represent a central component of the American political system with some analysts claiming that it helps keep that system in balance (Bednar Reference Bednar2008; Nugent Reference Nugent2009). The empirical analysis that follows offers a window into the operation of these political safeguards in an era of partisan polarization and seemingly heightened conflict between the national government and the fifty states. Is the system working largely as intended, or is it somehow out of balance?

In addition, the novel dataset described in this section provides an analytical opportunity to systematically assess whether and how legislative content affects the amount of progress that a given bill or resolution makes. Such an assessment is possible for two reasons. First, as the next section describes in more detail, there is considerable variation in legislative outcomes. Some proposals challenging national policies were signed into law and some were endorsed by one or two chambers, but state legislators did not take action on others after they were introduced. Second, the proposals vary in the nature of the challenge they pose to the national government, providing an opportunity to take an even closer look at the relationship between the specific language used in a proposal and its legislative progress. The four specific categories on which the analysis will rely—true nullification, nonacquiescence, procedural resistance, and nonfederalism-related—are well suited to evaluating whether the content of a proposal shapes its likelihood of success.

Analysis

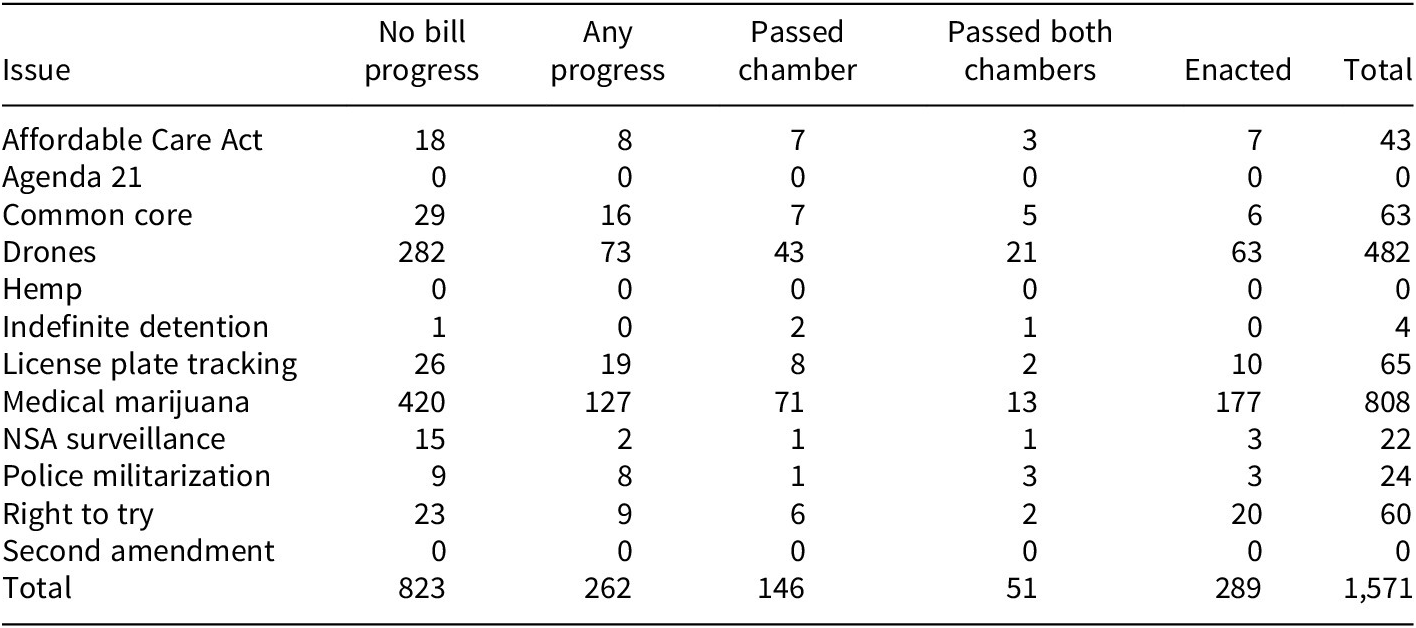

Does legislative content affect the amount of progress that bills and resolutions make toward enactment? Specifically, do proposals that challenge national policies systematically make more or less progress compared to proposals that lack federalism-related content? The descriptive statistics in Table 1 imply that resistance-related legislation has had a meaningful impact on state political agendas and is not mere posturing or position-taking. Of the 2,582 federalism-related proposals in our study, legislators took action on 1,114 of them (43.1%), investing time and energy by at least holding hearings. Moreover, 451 of those proposals (17.5%) cleared two chambers of the state legislature, and 367 of them (14.2%) were signed into law. Critically, however, legislation that did not challenge national policies, which are labeled nonfederalism bills in Table 1, appear to make more progress toward enactment than resistance efforts. Strikingly, 1,621 of these 2,600 proposals (62.3%) saw at least some action taken by state legislators with 868 of them (33.4%) signed into law. At least descriptively, it appears that federalism-related efforts are less likely to make legislative progress and be signed into law than other legislation identified using the same search strings.

Table 1. Legislative progress by issue area, 2009–2016

Comparing the federalism-related proposals to one another is also revealing. It suggests that legislative outcomes differ considerably based on the nature of the challenge to national policy. While 47.6% of the procedural proposals saw at least some progress toward enactment, only 37.1% of the nonacquiescent proposals and 31.0% of the true nullification attempts saw similar results. These differences become even more pronounced at the enactment stage. Only 8.4% of the nonacquiescent proposals and 3.9% of the true nullification proposals were enacted into law; in contrast, 18.4% of the procedural proposals were adopted.

These descriptive statistics are suggestive, but it is essential to account for other factors with the potential to affect legislative outcomes before drawing any firm conclusions about the importance of legislative content. The next step in our empirical analysis is therefore to conduct a multivariate analysis that combines information about individual proposals with data on potentially relevant sponsor characteristics and state attributes. Given our interest in legislative progress, the dependent variable in the multivariate analysis is an index that reflects the different stages of the lawmaking process. A bill or resolution receives a score of “0” if the chamber does not take further action after its introduction. Most state legislative sessions are short and agenda space is limited, so almost half of the initiatives in the dataset fall into this category. All the other proposals made at least some headway through the policy process. A legislative proposal receives a score of “1” if a committee held a hearing or took some other action on it, but it was not endorsed by the entire chamber in which it was introduced. Initiatives that cleared one legislative chamber receive a score of “2,” and those endorsed by two legislative chambers receive a score of “3.” If a proposal was signed into law by the governor (or became law over his or her objections), it receives a score of “4.” The ordinal index that results from this coding scheme is a proxy for the political success of the proposals in the dataset.Footnote 12

The question that motivates this study is whether the intergovernmental content of a bill affects its legislative prospects. The multivariate analysis that follows therefore includes bills without intergovernmental implications and proposals that challenge national policies to varying degrees. It assesses their comparative progress toward enactment. The critical independent variables are dichotomous indicators that correspond to the type of challenge that a proposal poses to national policy with separate indicators for true nullification, nonacquiescent legislation, and procedural legislation; nonfederalism related legislation serves as the reference category.

In analyzing legislative outcomes, it is necessary to account for other politically relevant characteristics of the proposals and their sponsors. While these characteristics are not the focus of the discussion that follows, they are included due to their potential impact on the policy process. Different types of proposals might be more likely to clear the various legislative hurdles they confront. Resolutions, which sometimes lack the force of law, might make more legislative progress because legislators perceive that there is less “at stake” than there is with conventional legislation. As a result, the models include a dichotomous variable indicating whether a measure is a resolution.Footnote 13

The models include six additional variables that account for the attributes of individual proposals. In an era of partisan polarization, it is essential to be attuned to levels of Republican and Democratic support for a given bill. The first bill-level measure is therefore a dichotomous variable that indicates whether a proposal’s primary sponsor is a Republican. Since political parties play a key role in legislative organization and the majority party often exercises control over the agenda, the second measure indicates whether the sponsor of a measure is a member of the majority, with the expectation that such bills will make more legislative progress. The extent of partisan unity or conflict surrounding a measure might also affect its prospects. On the one hand, a proposal might have a stronger likelihood of success if it is backed by most of a legislative caucus. The models therefore include a “net sponsor advantage” measure that is the absolute value of the difference between the number of Republican and Democratic sponsors and cosponsors. On the other hand, bipartisan support might also improve a measure’s prospects. Sometimes the primary sponsor of a bill is joined by his or her colleagues from the other party as cosponsors, and on rare occasions the primary sponsor can even be outnumbered by their partisan opponents. The models therefore include a dichotomous “opposite party” variable that indicates whether the party of the primary sponsor is outnumbered. Another bill-level variable indicates whether the sponsor of a bill is a legislative committee rather than an individual, and the final bill-level variable indicates whether the primary sponsor is a woman. Female legislators tend to be more active on certain types of policy issues (Cammisa and Reingold Reference Cammisa and Reingold2004; Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Swers Reference Swers2002), and those differences might affect a proposal’s legislative prospects.

Numerous characteristics of the state in which a proposal is introduced are also likely to shape its likelihood of success. The models therefore include measures that account for important features of the institutional, political, and socioeconomic environment. The first one is a control variable that accounts for variation in the institutional rules that govern the lawmaking process. Of the 99 state legislative chambers in the United States, nearly one-quarter require committees to hold a hearing for every piece of legislation over which they have jurisdiction (Anzia and Jackman Reference Anzia and Jackman2013). These requirements are expected to contribute to more legislative progress since our index includes committee action. Patterns of partisan control are just as important at the state level as they are at the bill level. The legislation in the dataset covers the period from 2009 to 2016. In a polarized era with a Democratic president, Republican state officials might be more inclined to support resistance to national initiatives. The models therefore include two measures of partisanship. The first is a dummy variable indicating whether the governor is a Republican; the second is a three-point count of the number of legislative chambers under Republican control (0, 1, or 2).Footnote 14 Of course, partisan polarization is not solely about intergovernmental relations. It can also generate conflict within states. Interparty collaboration might be especially unlikely in highly polarized legislative chambers, leading to gridlock and stalemate. The models therefore include measures of house and senate polarization that account for the distance between the median party member in each legislative chamber (Shor Reference Shor2018; Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2011). The models also include a variable indicating whether divided government, where no single party exercises unified control over the governorship and state legislature, exists in a state. The existence of divided government is frequently described as an obstacle to the passage of legislation.

The models also include a proxy for state ideology, namely, the percentage of the presidential vote the Democratic candidate received in 2008, 2012, and 2016.Footnote 15 States that are less supportive of the president may offer more resistance to national policies, producing a negative relationship between ideology and legislative progress. There are other ways to measure ideology at the state level, but presidential vote share seems especially appropriate in this context, and it has also been used to examine state resistance to national initiatives like the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001 (Shelly Reference Shelly2012).

In addition to investigating the potential influence of partisanship and ideology on the legislative progress of resistance-related legislation, the models also assess whether resource availability is an important contextual factor. Just as the earliest adoptions of innovative policies tend to occur in states with the financial capacity to invest in policy design and implementation (Boehmke and Skinner Reference Boehmke and Skinner2012; Rogers Reference Rogers1995; Walker Reference Walker1969), less affluent states may be supportive of resistance-related efforts because they chafe at the fiscal requirements imposed by national initiatives. Resource availability has also been associated with more populous states, and officials in states with larger populations may be more supportive of resistance-related efforts because they are predisposed to view their jurisdictions as autonomous entities that can operate independently of the national government (Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2012; Olson, Callaghan, and Karch Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018; Shelly Reference Shelly2012). In addition, the models include a measure of legislative professionalism, which is associated with higher salaries, longer sessions, and greater staff resources (Squire Reference Squire2007). Legislative professionalism is not usually linked directly to resource availability, but lawmakers in professionalized chambers may have more confidence that they can operate independently from the national government. However, a recent study identified a significant negative relationship between legislative professionalism and resistance to NCLB (Balla and Deering Reference Balla and Deering2015), so the impact of this variable is uncertain.

The models also include two measures that account for the potential impact of outside interest groups on legislative outcomes. The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is a powerful actor at the state level (Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2014, Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019), and it played an especially important role in state-level resistance to the policies of the Obama administration by drafting and disseminating model legislation on various topics. The two measures included in the models are the number of ALEC model bills introduced and the number of ALEC model bills enacted in a state. These measures are proxies for the degree to which this organization influences the policy process at the state level.

Finally, the models account for the distinctive history of true or pure nullification in the United States. Since the doctrine of nullification is often associated with the Civil War and was used to justify secession, the models include a dichotomous variable that indicates whether the state in which a bill was introduced is in the South. Southern states may be especially predisposed to challenge national government policies due to this historical legacy and the distinctive features of southern politics (Key Reference Key1984).

To study the influence of bill-level and state-level factors on the likelihood of a given proposal gaining enactment, our analysis relies on random intercept proportional odds models. These multilevel models allow us to account for characteristics of the bills themselves as well as chamber and state level factors that could alter the progress that a proposal makes through the legislative process. Critically, this model specification allows us to do so while accounting for the ordinal nature of our dependent variable.Footnote 16 In each of our tables, the first model presents log odd results and the second model presents odds ratio results.Footnote 17

Results

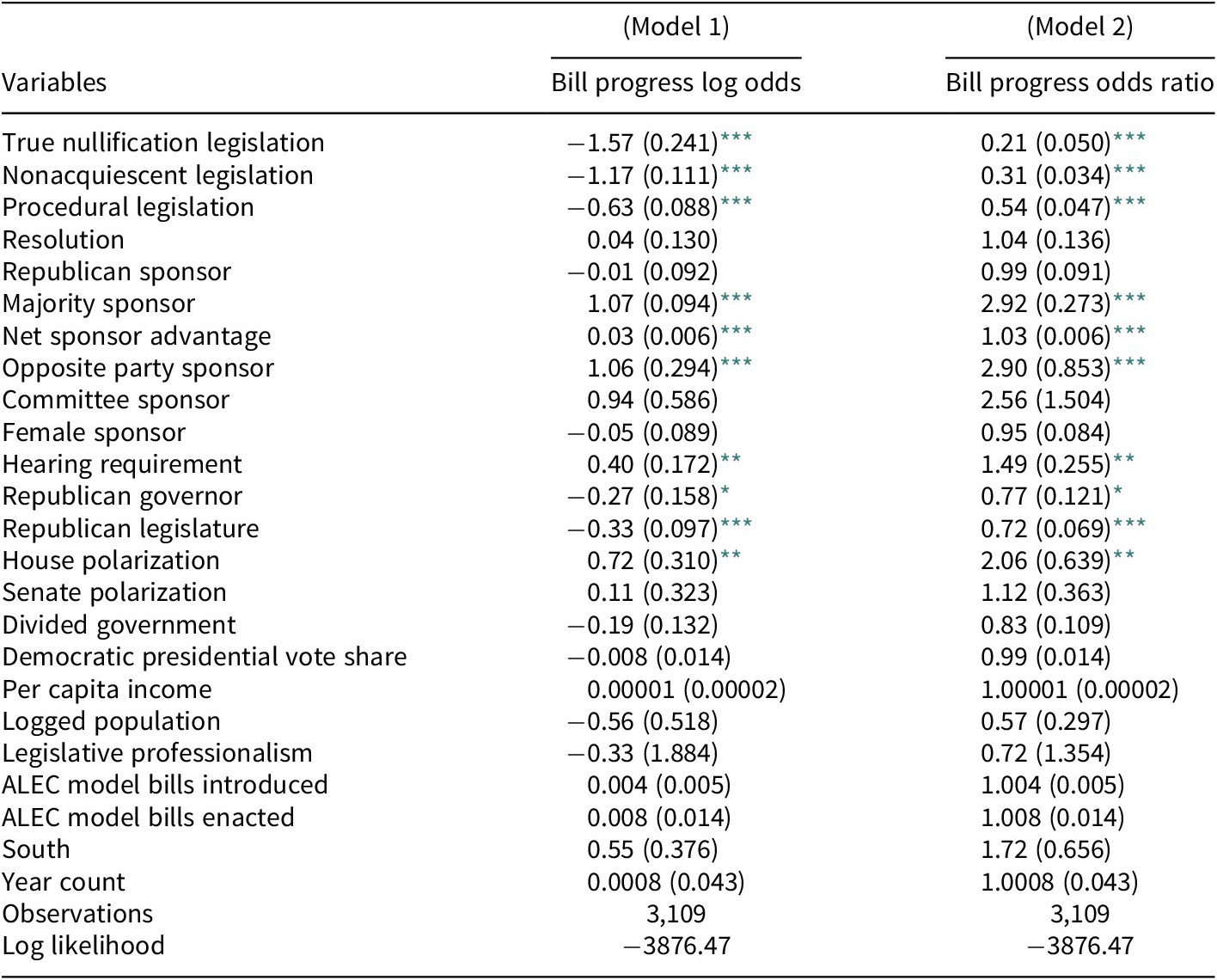

Do proposals that challenge national government policies experience systematically different legislative outcomes than other legislation while controlling for bill and state level characteristics? Table 2 examines this important question for a large set of proposals that were introduced from 2009 to 2016. It identifies three noteworthy patterns. First, confirming our descriptive results, state efforts to oppose the national government make less progress towards enactment than all other types of state bills. Specifically, Model 2 in Table 2 shows that procedural bills are 46% less likely to make progress toward enactment; the comparable figures for nonacquiescent and true nullification bills are 69% and 79%, respectively.Footnote 18

Table 2. The impact of bill and state characteristics on legislative progress

Note. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01;

** p < 0.05;

* p < 0.10.

Second, Table 2 reveals that several bill-level factors increase the progress of state legislation toward enactment. Our analysis demonstrates, for example, that having a majority party sponsor and increasing the size of the sponsor advantage increases the likelihood of bill enactment by 2.92 and 1.03 times, respectively. Additionally, Table 2 shows that having a primary sponsor who is outnumbered by cosponsors from the opposition can be an advantage in getting legislation passed, as it increases the odds of enactment by 2.90 times. Lastly, the positive and significant finding for our hearing requirement measure highlights the need to include that control because the application of this institutional rule, not surprisingly, leads to more progress toward passage.

Finally, Table 2 reveals that state-level predictors have a limited impact on legislative progress toward enactment. Measures for legislative professionalism, presidential vote share, population, income, and the extent to which states use model legislation all fail to attain conventional levels of statistical significance when controlling for content and bill-level characteristics. The only significant predictors of legislative progress at the state level are partisan in nature. We find that a one-unit increase in Republican control of the state legislature decreases the odds of a bill passing versus being in a lower category of progress by 28% and having a Republican governor decreases them by 23%. This pattern suggests that, during the Obama administration, states with Democratic control of state government were more likely to enact the legislation that they pursued.

While the results presented to this point largely meet our expectations, it is important to note that a single-issue area could be having an outsized influence on our findings. Specifically, medical marijuana proposals comprise nearly 40% of the bills that challenge the national government in our dataset (1,028 of 2,582 bills), and this might bias our results. Even though the TAC considers medical marijuana legislation to be a form of state-level resistance, the position of the national government on this issue has fluctuated significantly over time (Hannah and Mallinson Reference Hannah and Mallinson2018; Pacula and Smart Reference Pacula and Smart2017). During the period covered by our empirical analysis, there was an implicit understanding between states and the Obama administration that the national government would not interfere with state policies on the topic. The US Department of Justice (DOJ), in its 2009 Ogden Memo and subsequent memoranda, stated that its core enforcement priorities did not include investigating and prosecuting individuals who were in unambiguous compliance with state medical marijuana laws.Footnote 19 This DOJ guidance led many states to update and tinker with existing laws, and sometimes these efforts sought to comply with the national government’s new position. The result was a fluid and complex situation in which state programs demonstrated remarkable heterogeneity along such dimensions as patient access, product safety, and dispensary practices (Klieger et al. Reference Klieger, Gutman, Allen, Pacula, Ibrahim and Burris2017; Pacula and Smart Reference Pacula and Smart2017).

The bills in our dataset reflect this variation. Some of them were expansive attempts to legalize medical marijuana. For example, a 2015 Louisiana bill sought to permit the prescription and dispensing of therapeutic marijuana.Footnote 20 In other cases, lawmakers introduced legislation with narrower objectives. In 2015, a Colorado bill allowed individuals on probation to possess and use medical marijuana.Footnote 21 One year later, Connecticut lawmakers considered a proposal that required the Commissioner of Consumer Protection to waive the registration and administration fees for veterans using marijuana for palliative purposes.Footnote 22 Finally, many proposals addressed oversight issues, including legislation in Hawaii that established a medical cannabis advisory board and transferred jurisdiction over the state medical marijuana program from the Department of Public Safety to the Department of Public Health.Footnote 23 Given the large number of medical marijuana bills, their heterogeneity, and the stance of the national government during the Obama administration, it is important to ask whether our results change if the bills are removed from our dataset.

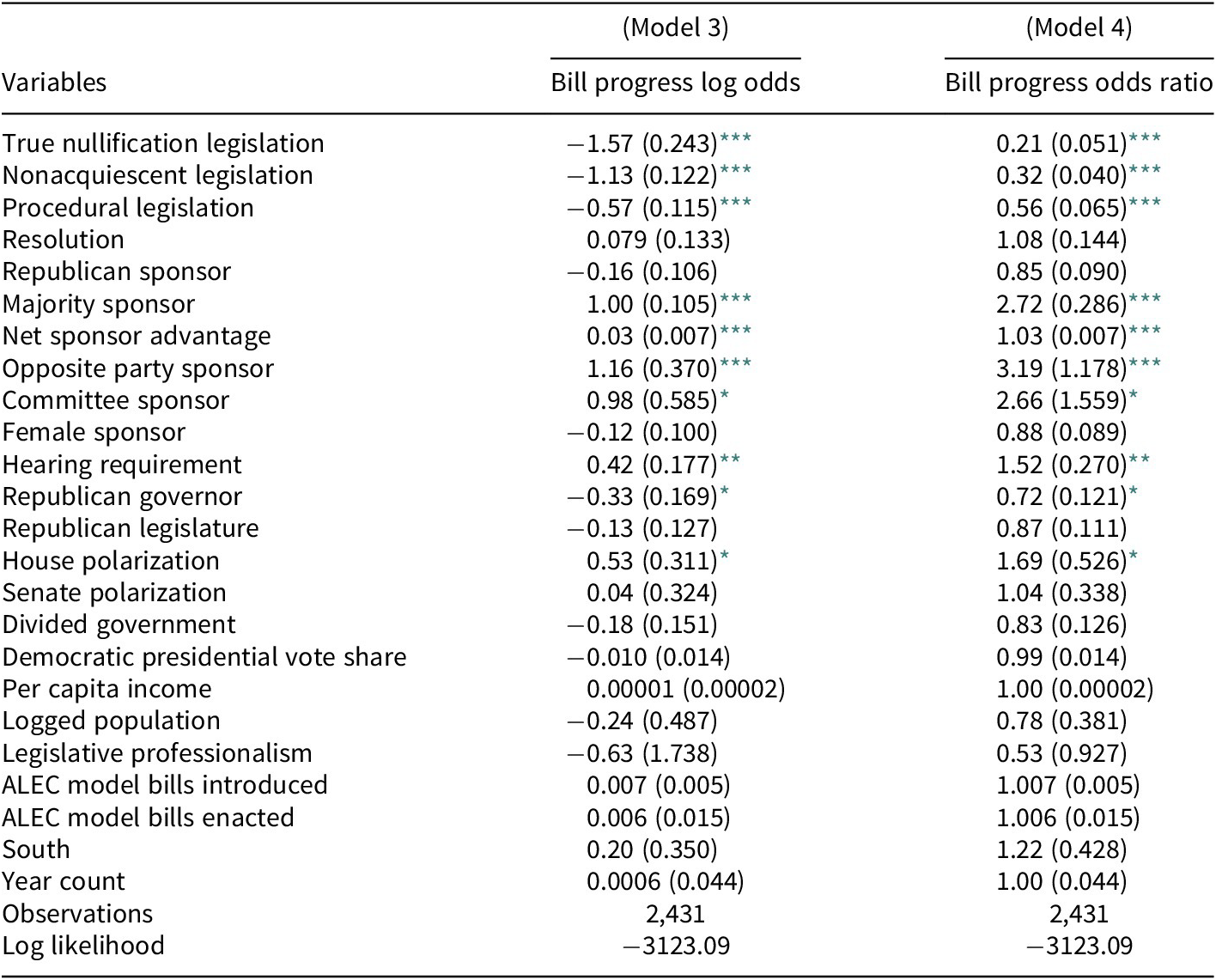

Table 3 analyzes this question in depth. It shows that, for the most part, the influential predictors identified in our initial examination have a significant impact on legislative progress even when medical marijuana proposals are excluded from the analysis. Most importantly, the results in Table 3 confirm that federalism-related efforts consistently make less progress toward enactment than other types of legislation. Specifically, procedural, nonacquiescent, and true nullification bills are 44%, 68%, and 79% less likely than other state legislation to advance even without medical marijuana bills included. Beyond the impact of legislative content, several controls remain robust to the alternative specification in Table 3. Only Republican legislative control no longer attains conventional levels of statistical significance. House polarization has a marginally significant positive effect in one of the models in Table 3, a result that is at odds with our expectations.

Table 3. The impact of bill and state characteristics on legislative progress excluding medical marijuana bills

Note. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01;

** p < 0.05;

* p < 0.10.

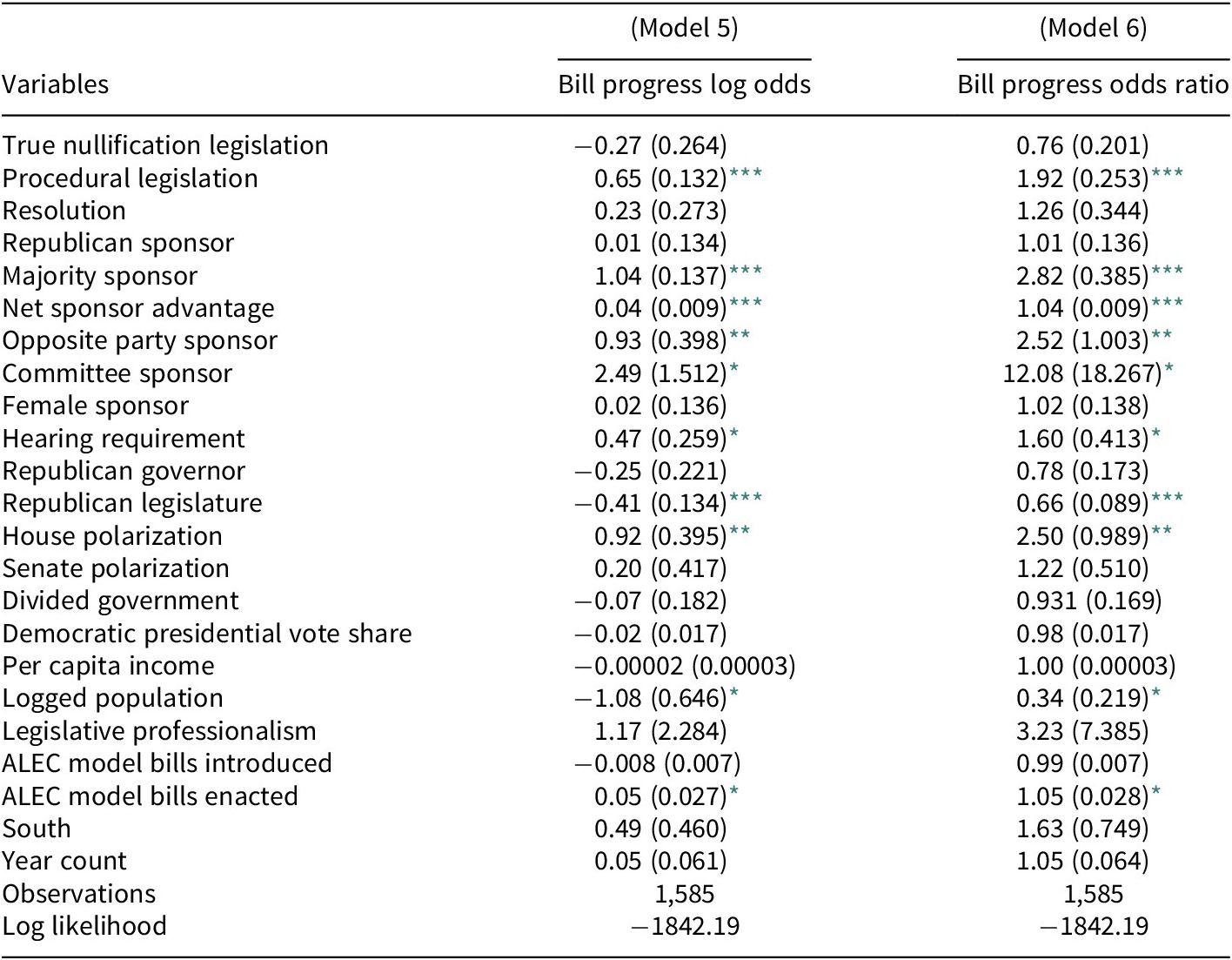

The analysis to this point has compared proposals that challenge national policy to bills and resolutions that lack federalism-related content. It is also important to compare the federalism-related proposals to one another. Doing so will provide another test of the hypothesis that legislative content affects the policy process. For that reason, our final analysis retains the same basic structure while excluding all the bills and resolutions that do not challenge national policies. In this new specification, nonacquiescent legislation serves as the reference group. Table 4 displays our results. It reveals that procedural resistance efforts are 1.92 times more likely to make progress toward enactment than nonacquiescent proposals. Notably, however, while the coefficient for true nullification legislation is negatively signed, it does not attain conventional levels of statistical significance. This finding suggests that true nullification bills are not significantly less likely than nonacquiescent legislation to be signed into law. The other results in Table 4 are very similar to those for the baseline model that includes all the state legislation. Having a sponsor in the majority, net sponsor advantage, opposition party sponsorship, and hearing requirements are all significant positive predictors of bill progress, as is House polarization. Committee sponsorship and the number of ALEC model bills enacted also have a marginally significant positive effect. Republican legislative control remains a significant negative predictor, but having a Republican governor no longer attains conventional levels of statistical significance. Finally, there is a marginally significant negative relationship between population and legislative progress.

Table 4. The impact of bill and state characteristics on the legislative progress of bills challenging the national government

Note. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01;

** p < 0.05;

* p < 0.10.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has important implications for the study of state politics, legislative politics, and American federalism. Its results suggest that state legislation challenging national policies makes significantly less legislative progress, all else being equal, than proposals that lack federalism-related content. Moreover, comparing federalism-related bills to one another suggests that the nature of the challenge to the national government affects the amount of legislative progress that a proposal makes. The decision by state officials to explicitly challenge the constitutionality of a statute as opposed to vowing not to implement it or changing the procedural requirements for its implementation has meaningful consequences. Our analysis finds consistent evidence that the less severe the rebuke of the national government is in a piece of legislation, the more likely the bill can marshal the support needed to gain enactment. This finding reinforces the need to distinguish among recent state-level challenges to national policies, validating a claim made by multiple federalism scholars (Dinan Reference Dinan2011; Olson, Callaghan, and Karch Reference Olson, Callaghan and Karch2018; Read and Allen Reference Read and Allen2012). More broadly, it suggests that scholars will enhance their understanding of the policy process if they engage more seriously with differences in the specific language and provisions embedded in bills and resolutions.

One could think of our analysis as an application of the notion of “policy as a prize” to the study of intergovernmental relations (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014). This notion postulates that public policies are so consequential that the ability to shape them is what motivates most enduring political actors. Control of state government provides one such prize—the ability to challenge and possibly undercut national laws. By investigating the potential link between the type of intergovernmental challenge that state officials pursue and their legislative success, this paper enhances our understanding of the conditions under which officials can claim “policy as a prize.” Specifically, it implies that the rewards of introducing pure or true nullification legislation are primarily symbolic (Edelman Reference Edelman1964). Placing these proposals on the agenda is an expressive act; it symbolizes resistance to the threat posed by a national government that has overstepped its authority. Such proposals are unlikely to become law or to be upheld by the judiciary if they are enacted, but they can communicate opposition and keep an issue alive. Procedural legislation, in contrast, is more likely to lead to tangible changes that move policy in the desired direction. Thus, state officials face a choice. They can lend their names to legislation that largely amounts to shaking one’s fist ineffectually at the national government, or they can pursue weaker forms of resistance that are more likely to make legislative progress.

Our results also identify several avenues for future research on contemporary tensions between the states and the national government. First, the consistent relationship between bill sponsor characteristics and legislative progress suggests that further inquiries into the role of individual legislators could yield valuable new information. Are ideologically extreme state legislators more or less likely to propose measures that challenge national policies or to endorse certain types of legislative challenges? Similarly, does lawmakers’ seniority alter their likelihood of introducing or cosponsoring bills that resist national policies? Alternatively, are there certain district-level characteristics that make state legislators more likely to take part in this sort of resistance? In addition to providing crucial information about the central actors involved in state-level challenges to national policy, answering these questions will illuminate the possible connection between intergovernmental tensions and partisan polarization. It would also be illuminating to expand the temporal and substantive reach of the empirical analysis featured here. Intergovernmental disputes also occur under Republican administrations, yet the nature of these conflicts and the exact issues at stake might differ. While the 12 issues examined here span the ideological spectrum, they are not exhaustive. Climate change, immigration, and “social” issues like abortion and same-sex marriage are topics that have sparked intergovernmental disputes in recent years but were not a part of this study.

Thinking broadly about contemporary intergovernmental relations in the United States, the patterns identified in this paper are somewhat reassuring. In an era of partisan polarization, state governments are exercising their ability to challenge the national government across a wide range of subjects. Yet the fact that these legislative challenges, all else being equal, make less progress than proposals that lack federalism-related content suggests that they are not doing so indiscriminately. Moreover, the least aggressive of these challenges—procedural legislation—make significantly more legislative progress than pure nullification or nonacquiescent bills. The importance of legislative content in this context is consistent with the conventional wisdom that American political institutions are more conducive to incremental change than to massive policy upheavals (Immergut Reference Immergut, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992; Steinmo and Watts Reference Steinmo and Watts1995; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). Moreover, given the shaky constitutional underpinnings of state efforts to invalidate national policies and the checkered history of the doctrine of nullification (Card Reference Card2010; Levinson Reference Levinson2014), it seems appropriate for these proposals to face relatively high scrutiny during the policy process. These observations suggest that the political safeguards of federalism remain alive and well in the early twenty-first century and may be operating exactly as the founders intended.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/spq.2020.5.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on UNC Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/PLKGGA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carol Weissert and Dick Winters for helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper and Lindsay Hirsh, Hannah Murrow, and Yang You for excellent research assistance.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Timothy Callaghan is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Texas A&M University School of Public Health. Dr. Callaghan received his doctorate in political science from the University of Minnesota and his research focuses on how politics, policy, and place work together to influence health in America.

Andrew Karch is Arleen C. Carlson Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. His most recent book, coauthored with Shanna Rose of Claremont McKenna College, is Responsive States: Federalism and American Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Appendix A

Issue Areas Addressed by State Legislation Challenging National Policies

Affordable Care Act (ACA)

Bills addressing the Affordable Care Act in our dataset oppose the ACA by either declaring the law null and void, prohibiting state actors from implementing health insurance exchanges or expanding Medicaid, or compelling state attorneys general to participate in lawsuits challenging the law.

Agenda 21

Agenda 21 is a nonbinding United Nations resolution that suggests ways for local governments and other actors to promote sustainable development. Bills in this category prohibit the adoption or implementation of policies associated with the resolution, often in sweeping language.

Common Core

Bills in this category resist the Common Core State Standards Initiative, a reform program associated with the standards movement in education. Many of them forbid state agencies from adopting and funding this initiative, prohibit the use of specific educational materials associated with it, or repeal previous actions that were taken to implement the Common Core.

Drones

Bills in this category address the use of drones, often emphasizing the warrantless use of drones for spying. Many of the bills limit the ability of law enforcement agencies to use drones without a warrant.

Hemp Farming

Bills in this category challenge a US Drug Enforcement Agency regulation that prevents the practice of growing industrial hemp. Many of them permit the production and possession of industrial hemp, often establishing a regulatory framework that includes a licensing procedure. Other bills in this category exclude industrial hemp from existing lists of controlled substances.

Indefinite Detention

Sections 1021 and 1022 of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 seem to allow the national government to hold individuals for an indeterminate length of time. Bills in this category generally declare these provisions unconstitutional and unlawful or prohibit state government assistance in any investigation, prosecution, or detention pursuant to them.

License Plate Tracking

Bills in this category address automated license plate reader technology that allows state agencies and municipalities to photograph license plate numbers. These bills prevent the use of license plate readers, limit their use to law enforcement, require warrants for their use, or regulate the length of time that license plate data can be stored.

Medical Marijuana

Bills in this category regulate the use of marijuana. They vary greatly but regulate the prescription and dispensing of medical marijuana, determine eligibility and set fees to use marijuana, and in some cases attempt to legalize medical marijuana in the state.

NSA Surveillance

The mass surveillance programs of the National Security Agency (NSA) expanded greatly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and involve the warrantless tracking of Americans’ phone calls, text messages, web-browsing activities, and emails. Bills in this category generally prohibit state or local government cooperation with the NSA’s collection of electronic data or metadata without a warrant.

Police Militarization

The 1033 program transfers excess military-grade weapons and equipment from the national government to local police forces and other civilian law enforcement agencies. Bills in this category either impose certain procedural requirements prior to participation in the program, implement various oversight provisions on the agencies that wish to participate, or prohibit the acquisition of certain types of weaponry.

Right to Try

Right to try legislation allows terminally ill patients to use pharmaceuticals that the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved for public use. Bills in this category regulate licensing board action against healthcare providers dispensing these experimental treatments and prevent state agents from blocking patient access.

Second Amendment

State attempts to challenge federal gun control legislation come in two main forms. The first type of legislation argues that firearms manufactured and sold in the same state are not subject to federal regulation. The second type of legislation claims that gun control is not an enumerated power of the federal government and therefore federal gun laws violate the Tenth Amendment.

Appendix B

Federalism-Related Bills by Type and Issue Area

True Nullification Bills

Non-Acquiescent Bills

Procedural Bills