1. Introduction and a “historically interesting” letter (1930) from Freud to Heinrich Löwy (and, by implication, to Richard von Mises) about his working method

The following article focuses on the transcript of an audiotaped interview (hereafter “the Interview”),Footnote 1 conducted on May 30, 1953 by the Austrian-American psychoanalyst Kurt Robert Eissler (1908-1999),Footnote 2 with two mathematicians, the married coupleFootnote 3 Richard von Mises (1883-1953, hereafter RvM)Footnote 4 and Hilda von Mises (1893-1973, née Geiringer, henceforth Geiringer),Footnote 5 in Cambridge near Boston (USA). Geiringer was born in Vienna, and RvM’s family had moved to the Austrian capital in 1890 from his birthplace Lemberg in Galicia (today Lvív in Ukraine). The purpose of the Interview was to collect information about the couple’s contacts to Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and to psychoanalysis. Six weeks later, on July 14, 1953, RvM, a pioneer of modern applied mathematics and of probability theory, died of cancer.

In the “Finding Aid” to the papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress,Footnote 6 there is one entry for the name “Mises,” which is the above Interview, with the designation “Von Mises, Hilda, 1953” in box 133. The given name “Richard” or R. appears nowhere in the Finding Aid or in the text of the transcript. Nevertheless, RvM, who was ten years older than his wife, was the main contributor to the Interview. RvM was able to recall events early in the century, like the Hervay affair (1904) and conflicts between Freud and his former close friend Wilhelm Fließ (1906),Footnote 7 events which for reasons of age both his wife and Eissler, the two other participants in the Interview, could not possibly remember. Throughout the Interview, RvM was addressed by Eissler as “Herr Professor,” while Geiringer, an internationally acclaimed applied mathematician as well and at the time professor at Wheaton College near Boston, had to be content with the then usual form of address “Gnädige Frau.”

In the following three sections I will offer a detailed commentary on the Interview and its background. As an appendix, I publish in English translation a very slightly shortened (mainly to avoid text redundancies and repetitions) version of the spaciously written 51-page German transcript, indicating corrections based on the audio file. Footnotes in the appendix refer back to the article’s commentary or explain minor points. Note that all page numbers cited in the article when quoting the interview refer to the pagination of the original German transcript, and not to the translation.

The celebrated Viennese essayist and journalist Karl Kraus (1874-1936), a scathing critic of the linguistic and ethical failings of his culture, plays a special role among the persons mentioned in the Interview. His periodical, Die Fackel (“The Torch”), was virtually required reading for educated Viennese, including Freud and RvM. The latter kept a complete run of the Fackel as he mentions in the Interview.

Nearly all the actors who appear in this article, not only the three participants in the Interview, but also Freud himself, Karl Kraus, Siegfried Bernfeld, and most of the others mentioned, had a Jewish cultural or religious background. The Viennese among them clearly tended in their opinions more toward the liberal, even “red” Vienna, although only a few of them, like Bernfeld and Geiringer, were close to Marxism and Social Democracy in their youth. Their Jewish origin and the prevailing anti-Semitism in the (Catholic) Christian Social Party and in the (mostly Protestant) German National Parties that supported “Black Vienna” (Wasserman Reference Wasserman2014, 120) and were close to people like the conservative philosopher Othmar Spann (1878-1950) would not have left them much choice anyway.

Roazen mentioned, in 1971, that the numerous Eissler interviews from the early 1950s were generally embargoed “for fifty to one hundred years” (Roazen Reference Roazen1971, 549). As can be seen from the interview with the Mises Couple published here, RvM also asked for temporary secrecy, although he was aware of the eventual public accessibility of the information he had given.Footnote 8 In particular, he believed that the three postcards in RvM’s possession written by Freud to Karl Kraus in 1906, which were discussed in the course of the Interview, could cast a skewed and unfavorable light on Freud. The controversy over Freud allegedly having dishonestly passed on Wilhelm Fließ’ ideas about biological periods and “bisexuality”Footnote 9 (ideas which are connected) was conducted in public in 1906, among other things, by the Fackel. RvM says in the Interview about Freud: “He used Karl Kraus as a journalist” (20,26).Footnote 10

This main reason for the secrecy of the Interview, however, essentially disappeared by 1961 at the latest, when Ernst Freud (1892-1970) published selected letters from his father in English translation. Among them was a letter from Freud to Karl Kraus dated January 12, 1906 (see below in section 3), which seemed to indicate even more clearly than Freud’s postcards that Kraus had been instrumentalized by Freud. A detailed and nuanced investigation of the “priority dispute,” which was actually more about Freud’s patient Hermann Swoboda and the then much-discussed eccentric genius Otto Weininger (1880-1903), was done by Michael Schröter (Reference Schröter2002, Reference Schröter2003). I discuss this further below in section 3, in connection with what the Interview says about the contacts between Freud and Kraus. First, however, a few remarks on the prehistory and the historical context of the Interview.

Freud’s daughter AnnaFootnote 11 had written to RvM from London on March 30, 1950. She had heard from the Viennese psychoanalyst Eduard (now Edward) Hitschmann (1871-1957),Footnote 12 who was living in the USA, that RvM had a “very interesting” letter from her father. Anna Freud asked RvM for a copy of the letter.Footnote 13 Anna Freud’s confidante in America, Eissler, wrote to RvM two years later, on December 24, 1952.Footnote 14 He had heard that RvM possessed two letters from Freud to Kraus, and was also interested in copies of any additional documents that might be relevant to Freud research. This request seems to have led to the Interview in May 1953.

The historical context of the Interview is perhaps best understood at the point where interviewer Eissler talks about the motivation behind his interview project and the entire Freud Archives:Footnote 15

Eissler: Freud needs interest in Freud, whether that interest will be there, we do not know.

RvM: Well, my private, unimportant opinion is that much of psychoanalysis will disappear. But Freud will not, Freud remains a great man!

Eissler: Well, I believe it depends on what direction civilization is going to go.

RvM: Well, except for the Atomic Bomb /laughs/. You mean in case it continues at all!

Eissler: Yes!

RvM: If it goes on, I do believe that this [psychoanalysis] is one of the great advances of mankind.

Eissler: But around the year 700 only very few people knew about Plato and Aristotle, at least in Europe. And here is something very similar, actually.

RvM: Yes!? What do you mean by that?

Geiringer: That it can perhaps come up again later, even if it disappears now for a century?

Eissler: Yes, I was thinking about something like that.

RvM: I don’t believe it. Today’s world isn’t really like that.

Eissler: Don’t you think that [we are living in] new Middle Ages, new spiritual Middle Ages [ein neues geistiges Mittelalter]?

RvM: Not today, the position of science is quite different, I believe. But I don’t have much to say.

The Interview took place during the height of McCarthyism (1950-1954). The “spiritual Middle Ages” cannot mean anything else than Eissler’s allusion to this environment. RvM, the scientist and believer in progressive, positivist thinking,Footnote 16 remained optimistic with respect to a survival of science. However, RvM was not naïve about the effect of the Cold War, of Stalinist ideology and McCarthyism on intellectual discussion. In a posthumously published manuscript on Positivism in May 1953, (i.e. in the month of the Interview), he wrote:

Any type of metaphysics, whether with or without religious shading, leads by its very nature to intolerance and injustice, makes a peaceful life and the pursuit of happiness for the whole of mankind impossible. If the present trends towards metaphysics in both camps go on unabatedly, are allowed to continue, the only imaginable future for both is the final attempt at physical annihilation of the counter-side. (Mises 1953, 547)Footnote 17

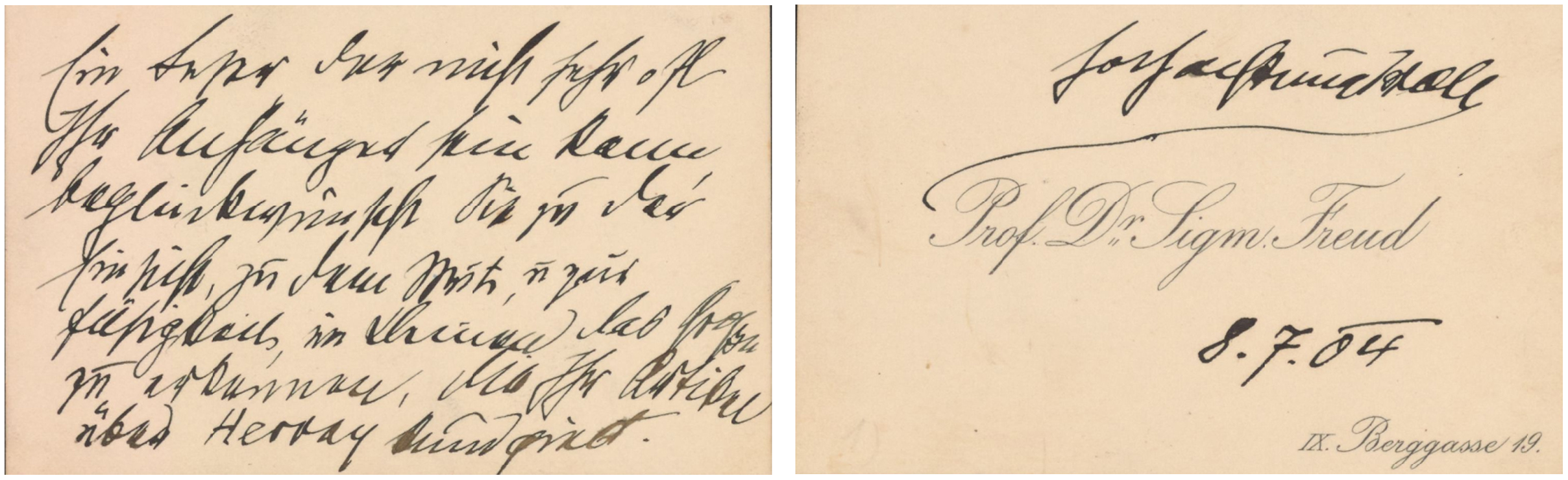

Eissler thanked RvM for the Interview in a letterFootnote 18 of June 3, 1953, and he did not forget to mention the special efforts RvM had to make because of his poor health. As he had already done during the Interview, Eissler guaranteed in this letter that all material relating to the Interview would remain strictly confidential according to RvM’s wishes. Eissler wanted the material to be given to the Library of Congress (i.e. the Sigmund Freud Papers) and to be embargoed there for at least fifty years. The material which was handed over to Eissler apparently included the original of Freud’s letter to Heinrich Löwy (1884-?)Footnote 19 of May 30, 1930 and RvM’s accompanying commentary, which are both reproduced below. The accompanying letter is one of the last letters written by RvM. Freud’s letter was a “scientifically interesting” letter („wissenschaftlich interessant,“ according to RvM’s words in the Interview), which answers an inquiry by Löwy and RvM. Freud’s letter, which apparently has been kept as an original in the Freud Papers since the 1953 Interview,Footnote 20 bore no obvious risk to cause offense and it was published as early as in 1961 in the aforementioned collection of letters by Freud’s son Ernst.

Vienna IX, Berggasse 19

March 30, 1930

Dear Doctor [Löwy]

Your biography of Popper-Lynkeus which accompanied your letter has pleased me so much by its dignity and truthfulness that I would like to comply with your wish and make a contribution to your collection of solutions to scientific problems. But in trying to find some suitable examples I have encountered strange and almost insuperable obstacles, as though certain procedures that can be expected from other fields of investigation could not be applied to my subject matter.Footnote 21 Perhaps the reason for this is that within the methods of our work there is no place for the kind of experiment made by physicists and physiologists.

When I recollect isolated cases from the history of my work, I find that my working hypothesis invariably came about as a direct result of a great number of impressions based on experience. Later on, whenever I had the opportunity of recognizing an hypothesis of this kind to be erroneous, it was always replaced—and I hope improved—by another idea which occurred to me (based on the former as well as new experiences) and to which I then submitted the material.

I am afraid the above will not be of any great use to your collection.

With kind regards

Yours sincerely

FreudFootnote 22

After the Interview, RvM sent an undated comment to Eissler, which must be considered as one of the last letters from RvM. It reads (in English translation):

The letter is directed to Dr. Heinrich Löwy (physicist, now in Cairo, Egypt), with whom I planned the edition of a “Collection of Examples” for the solution of scientific problems. He had asked Freud for a contribution. The plan has not been realized.

The biography of Popper-Lynkeus mentioned in the beginning of the letter has appeared in “Jüdisches Lexikon” [Löwy Reference Löwy, Herlitz and Kirschner1930].

In the following introductory commentary, I will attempt to outline the historical significance of the Interview in two sections, focusing on three main points. These are briefly formulated as follows:

-

Remarks on the reception of psychoanalysis and the perception of Freud by the three participants of the Interview at different points in time in the first half of the century, especially how the Mises Couple encountered Freud and psychoanalysis on various personal, political, and philosophical levels.

-

Addition to and correction of genealogical remarks made in the Interview.

-

The relationship between Sigmund Freud and Karl Kraus, primarily using the example of the conflict between Freud and Fließ, and secondarily using the so-called “Hervay affair” as an example. The discussion takes place from the perspective of some postcards from Freud to Kraus, which were in the possession of RvM in 1953.

For each of the three points, I shall draw on published and unpublished sources, especially material relating to RvM, and on literature, especially archive materials and publications by RvM and Geiringer. Perhaps the most important topics and unknown documents—beyond the Interview—that enter into the discussion and are briefly discussed in the commentary below, are

-

The failed application of Siegfried Bernfeld, the Freud student mentioned several times in the Interview, for a teaching position at Berlin University (1931). RvM was significantly involved in the Berlin faculty decisions. My work complements earlier German accounts of Tenorth (Reference Tenorth, Hörster and Müller1992, Reference Tenorth1999) and Dudek (Reference Dudek2012). RvM’s rather distant relationship to Bernfeld’s and S. Feitelberg’s attempt to connect thermodynamics and psychoanalysis (libidometry) confirms RvM’s critical attitude vis-à-vis certain theories of physicalism supported by the Vienna Circle of Logical Empiricism. This modifies the common picture which represents RvM as a follower of the Circle.

-

An unknown letter (1931) from the Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler to RvM in connection with Bernfeld’s failed application.

-

Geiringer’s activity in the Austrian youth and adult education movement with regard to the role of psychoanalysis.

-

A hitherto largely unknown letter from Karl Kraus to Freud dated September 16, 1906, which sheds new light on the relationship between Freud and Kraus, and on Freud’s position vis-à-vis the Fackel.

Another aspect of the Fließ Affair will be dealt with in the short fourth and concluding section of the commentary: RvM was not only interested in Wilhelm Fließ’ theory of bisexuality. As an applied mathematician he was also interested in Fließ’ theory of biological periods. The positive review of Fließ’ paper on the latter theory (Fließ Reference Fließ1906a) by the famous chemist and philosopher of science Wilhelm Ostwald (Reference Ostwald1907) may have increased RvM’s interest in this theory. The one-sided public discrediting of the theory by Martin Gardner (Reference Gardner1966) and Frank J. Sulloway (Reference Sulloway1979) is contrasted below with a statement by RvM (1926).

For the biographies of RvM and Geiringer and their importance as mathematicians I refer to separate literature in the bibliography (cited above). From the outset, it should be taken into account that both mathematicians were and remained closely connected to Freud’s Vienna. They had successful lives as applied mathematicians behind them in 1953, but also lives that were marked by their flight to the USA from Hitler’s Germany via the intermediate station of Turkey. Typical traits of RvM in particular stand out in the Interview, such as his strong self-confidence and a certain condescension towards colleagues whom he regarded as intellectually below his level (here visible in some general slights against colleagues in Strasbourg and in the USA). Also in evidence is his intellectual leadership and somewhat paternalistic attitude towards Geiringer, which she—herself an important applied mathematician—tolerated. This is reflected in smaller remarks in the Interview, like those concerning graphology, masochism, etc.

The information contained in the Interview is illuminating on multiple fronts. It contains accounts of atmospheric changes in the reception of psychoanalysis and of Freud over nearly half a century. Contemporary historical details, such as the travel conditions between Austria and Germany after the end of World War I, also provide interest for the overall historical picture. Finally, though RvM and Geiringer, two pioneers of modern applied mathematics, were not psychoanalysts, the Interview may nevertheless contribute to the understanding of the historical impact of psychoanalysis beyond medical, psychological and philosophical circles. As far as the historical accuracy of the Interview is concerned, it should be noted that we have no information whatsoever about how thoroughly the participants prepared themselves for itFootnote 23 and to what extent their statements reflect the complete state of their knowledge.

2. Richard von Mises, Hilda Geiringer, and Freud

2.1. Personal and genealogical connections

In the first third of the Interview, RvM repeatedly discusses genealogical matters and personal encounters with members of the Freud family, but he remains rather vague. His dating of the few personal encounters with Sigmund Freud to the early 1920s seems doubtful, as he claims that “as a young mathematician” he did not dare to talk with Freud about substantive aspects of psychoanalysis at that time. From RvM’s biography, on the other hand, we know of his great personal self-confidence and of his philosophical reflections and publications from the beginning of the 1920s. RvM says in the Interview explicitly: “I am not a 100% fan of psychoanalysis, but of Freud I am. He is a great man after all. … My private, unimportant opinion is that much of psychoanalysis will disappear. But Freud will not, Freud remains a great man!” (36–37). Later in the interview, however, he says something in contradiction to this, declaring: “I do believe that this [psychoanalysis] is one of the great advances of mankind” (37). RvM also reports short personal meetings with Freud’s mother Amalia, née Nathansohn, and with Freud’s wife Martha, née Bernays. He describes both of them as not very erudite and not well informed about Freud’s intellectual achievements. Martha he rather distantly calls a “Zetzen” (Austrian slang for tiresome person). As an example, he mentions a trip with her via Prague to Berlin around 1920.

Geiringer attended Freud’s lectures in 1916/17, but she had no personal meetings with Freud. She describes Freud’s personality as impressive, but is somewhat contradictory in her statements about what this impression was based on, especially whether his lectures were clear and understandable. On the other hand, she knew Freud’s children Anna, Ernst and Martin personally, but says in the Interview: “I was not close [intim] with them” (46). However, Geiringer must have had repeated contact with Anna Freud within the adult education movement (Volkshochschulbewegung) and in Siegfried Bernfeld’s personal environment (see below).

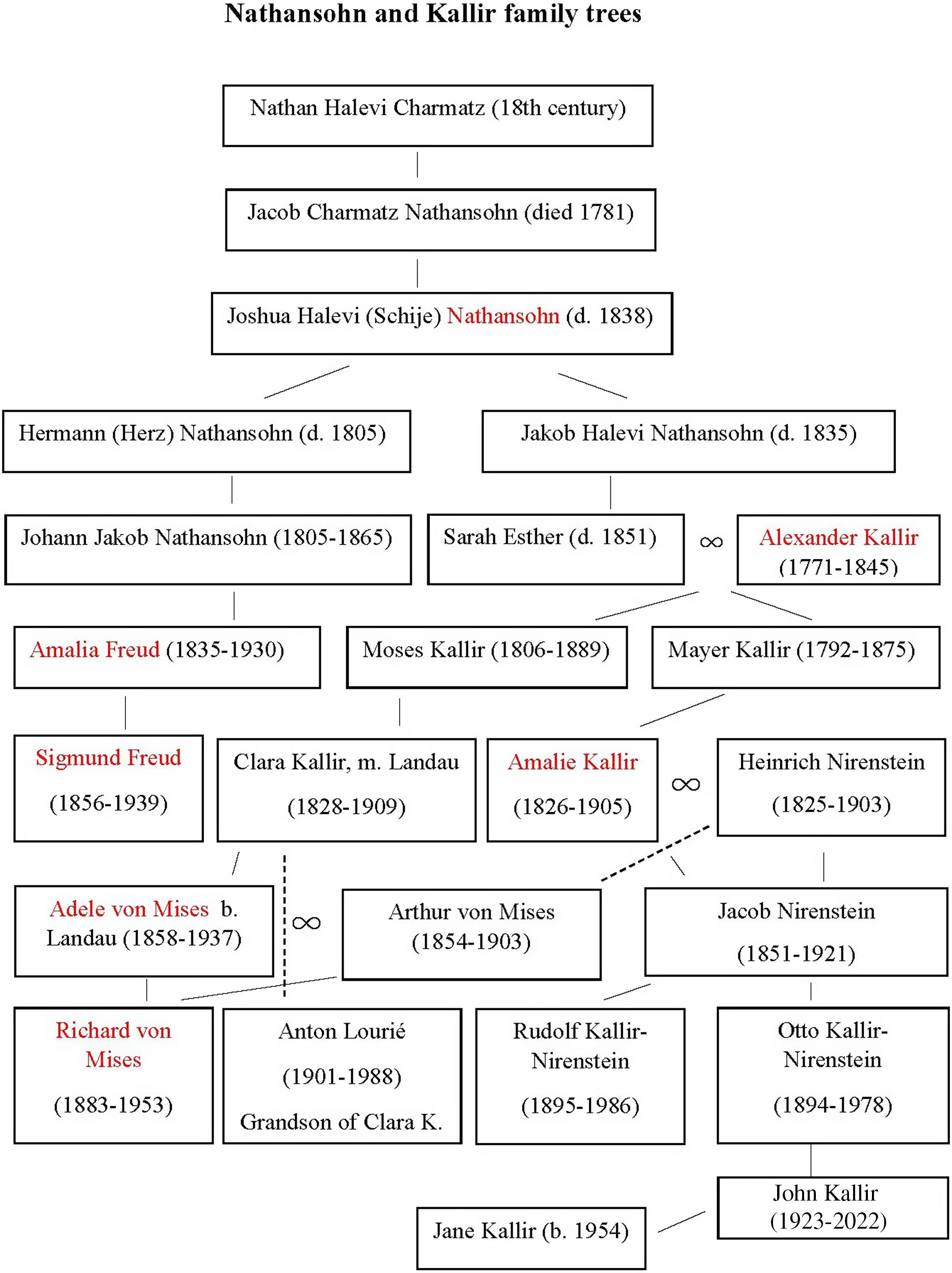

In the Interview, RvM repeatedly emphasizes his blood relationship with Sigmund Freud through his mother Adele, née Landau, and the Nathansohn family from Brody, which led to occasional encounters with the Freud family. However, according to RvM the kinship was “weak” (4). RvM also claims that Freud’s mother was connected to the bank Nathansohn & Kallir and therefore must have had a large dowry. He uses this to explain that Sigmund Freud, contrary to some statements in the literature, could not possibly have grown up in difficult financial circumstances.

It turns out that RvM’s information is very imprecise and not based on detailed knowledge of the pedigrees. Again, the spontaneous atmosphere of the Interview must be taken into account here (as throughout), and it cannot be ruled out that RvM would have expressed himself differently if he had reflected more thoroughly. Selected branches from the Nathansohn and Kallir family trees are presented in an appendix to this paper, not only in the interest of the comprehensibility of the Interview, but also because of the general importance of these Jewish families (see appendix 1).

The family relations are most compactly described by RvM’s mother Adele (née Landau, 1858-1937) in her well-written German memoirs of her youth in Brody in Galicia, which contain a chapter “The Nathanson [sic] and Kallir families,” and are available online from the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City (Mises Reference Mises1929).Footnote 24 Adele wrote the memoirs in 1929 for her niece Elisabeth Eliasberg (né Lourié), and (apparently) for her nephew Anton Lourié, who is mentioned in the Interview.Footnote 25

According to the family tree (appendix 1) Adele Landau was very remotely related—through their common progenitor Joshua Halevi (Schije) Nathansohn—to Amalia Freud, who was two steps above her in the generational line and thus a distant great-aunt of Adele. Similarly, RvM (born 1883) and Sigmund Freud (born 1856) were also two generations apart, despite an age difference of only 27 years.

It seems that the applied mathematician RvM was somewhat too hasty in the Interview, with insufficient knowledge of the concrete “heritage arithmetic.” In particular, at one point in the Interview he seems to confuse Amalia Freud, née Nathansohn, with Amalie Nirenstein, née Kallir. The fact that RvM’s distant cousin Otto Nirenstein had adopted the name Kallir may have misled RvM to the assumption that Otto’s grandmother Amalie Kallir was a born Nathansohn. At one point during the Interview (3) RvM must have thought that Freud was an uncle of Otto Kallir. This confusion seems to be the main reason for RvM’s erroneous assumption that Amalia Freud was close to the Nathansohn & Kallir bank. His mother Adele was apparently much better informed about this (Mises Reference Mises1929).

2.2. Encounters of the Mises Couple with Freud’s follower Siegfried Bernfeld through the Viennese youth culture movement (Geiringer before 1921) and the Berlin Philosophical Faculty (RvM 1930–31)

Geiringer attended Freud’s lectures on psychoanalysis as a mathematics student in Vienna in 1916/17. She says in the Interview that this must be seen as part of her political activities, especially her involvement in the Viennese youth and adult education movements, and that she also attended a seminar with the famous sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920). She had already read some of Freud’s works before attending his lectures. It was fashionable in her circles at the time to use psychoanalytic jargon.

Geiringer’s publications from her youth—that is, before she worked as a mathematician with RvM in Berlin—leave no doubt about her feminist, socialist, and, in part, Marxist convictions. One of these publications (Geiringer Reference Geiringer1920) is used in the literature today as an essential source for the description of a short-lived “proletarian school community” (Kinderheim Baumgarten west of Vienna, 1919–20), in which Geiringer herself was involved as a teacher (Dudek Reference Dudek2012). This project was led by the Freud supporter, pedagogue, and socialist Zionist Siegfried Bernfeld (1892-1953).Footnote 26

Bernfeld’s name appears at various points in the Interview, first in connection with the biographical article on Freud (Bernfeld & Cassirer Reference Bernfeld and Cassirer-Bernfeld1944). This article was partially criticized by RvM, especially with regard to biographical and genealogical information contained therein. However, RvM and Geiringer had an even closer relationship with Bernfeld on various levels other than those the Interview suggests.

From the Siegfried Bernfeld Papers in the Library of Congress, especially from the letters from Geiringer to Bernfeld dating from around 1920, the close personal and political relationship between Geiringer and Bernfeld, who were only one year apart in age, is evident.Footnote 27 It seems no coincidence that Geiringer subsequently corrected her original formulation in the Interview “close friend of Bernfeld [intime Freundin]” to “very good friend” (2). Geiringer was of course aware of the ambiguity of the German word “intim”.Footnote 28 On January 16, 1921, Geiringer wrote to her friend Bernfeld, alluding to an earlier phase of apparently even closer ties: “You said that you didn’t feel like ‘psychoanalyzing’ me (I too was too inhibited) because that would make a personal relationship of mutual affection, which we both wanted at the time, impossible or jeopardized.”Footnote 29

From the early 1920s, Bernfeld became increasingly prominent in publications, and also as a practicing psychoanalyst, and his friend Geiringer tried to learn psychoanalysis from him. This was particularly in the context of her efforts to gain a deeper philosophical understanding of her own science, mathematics, in which she had received her doctorate in 1917 with a very theoretical (i.e. apparently distant from applications) topic on Fourier series under Wilhelm Wirtinger (1865-1945) in Vienna. Geiringer’s efforts culminated in her book The World of Thoughts in Mathematics (Die Gedankenwelt der Mathematik), which appeared in 1922 in a book series in Berlin and Frankfurt (Geiringer Reference Geiringer1922). The series was connected with the German and Austrian adult education movements.

Before the book was published, Geiringer wrote several letters to Bernfeld about its contents and about her efforts to use psychoanalytic interpretative elements in her work. On June 20, 1920, she wrote to Bernfeld: “I am now very, very much looking forward to mathematics, to all its wonderful strict abstract unreality. But I will learn psychoanalysis after all. I’m sure I understand a little bit of it now.”Footnote 30 On October 26, 1920, she wrote to Bernfeld after explaining her book project:

It goes without saying, it is almost a commonplace that science, like art, … etc., obeys an external and an internal drive. The latter is usually negated. When this became very clear to me, I thought I understood why you spoke of a one-sidedness and the need to supplement the material [istic] conception of history with psychological considerations…. Perhaps a psychoanalysis of science would help to find out (I asked Heinz [Hartmann] whether the existing psa [psychoanalysis] of art was useful, he said it accomplished little). In such a case, a psa of math, as you suggest, would certainly be a good start, because mathematics is such a specific knowledge and such a deeply rooted and characteristic one.Footnote 31

Interestingly, Geiringer connects psychoanalysis primarily to the more abstract part of mathematics, not to the field which would later dominate her interest: applied mathematics.

In the book itself, however, Geiringer was rather ambivalent about the explanatory potential of psychoanalysis for mathematics and its history, arguing that “it is still a question whether it will be reserved exactly for psychoanalytical investigations … to make the almost mystical magic comprehensible, which lies precisely in the problems of mathematics that are most alienated [entfremdet] from reality. In any case, here lies a key to a still deeply closed chamber” (Geiringer Reference Geiringer1922, 160).Footnote 32 Moreover, regarding the Baumgartner School Project, Geiringer writes of a “(still very imperfect) application of psychoanalysis” (Geiringer Reference Geiringer1920, 114).

In an otherwise very positive review of Geiringer’s book on The World of Thoughts in Mathematics, RvM wished his then assistant “here and there a somewhat clearer and more mature judgement” (Mises Reference Mises1922, 224). Geiringer, like many others who had to find their career paths, later hardly mentioned her political involvement in Vienna during the war and postwar period, probably warned by episodes such as the one around 1927, when political prejudices of colleagues in the background seem to have threatened her habilitation procedure in Berlin (Siegmund-Schultze Reference Siegmund-Schultze1993). In the 1953 Interview, Geiringer felt the need at one point to apologize for the socialist convictions of Bernfeld, who had died shortly before in America: “Bernfeld’s social convictions should do you no harm. I think he always meant [it well]” (49). The “apolitical” (i.e. in reality strongly anti-Communist) environment in the United States at this time, as described in the introduction, may have contributed to Geiringer’s trivialization of Bernfeld’s political positions.

RvM’s contacts with Bernfeld were on a completely different level, more professional than political, from those of Geiringer.Footnote 33 Geiringer, who had been privately as well as professionally close to RvM since the late 1920s, was most likely informed about that.Footnote 34 In two papers (Tenorth Reference Tenorth, Hörster and Müller1992, Reference Tenorth1999) Heinz-Elmar Tenorth has documented that the Faculty of Philosophy of Berlin University in 1930/31 rejected a ministry-supported psychoanalytic lectureship for Bernfeld, although there was a very positive report from Sigmund Freud himself.Footnote 35 Tenorth’s research was further extended in Dudek’s book (2012). The faculty’s negative opinion of June 25, 1931, states, among other things:

According to the impression that Bernfeld’s writings, including the essay “Is Psychoanalysis a World View,” give to the reader, psychoanalytic teaching is an inviolable dogma that does not need proof. And if he expressly emphasizes the destructive effect that this—his—science can have (while one usually tends to praise the constructive powers of science), the fear that the universal method, to which psychoanalysis is extended here, could be exploited for purposes of agitation that go beyond the planned teaching assignment, does not seem unfounded. How little this could be reconciled with the teaching tasks of the university needs no explanation. As far as the fundamental position on psychoanalysis is concerned, the faculty is not able to recognize it as a science in its present state. (Dudek Reference Dudek2012, 435-36, my translation)

Already in this part of the statement, the faculty’s bias against psychoanalysis as a science, and also unfairness towards Bernfeld, is evident, because in the quoted essay by Bernfeld one can read (at the very beginning) roughly the opposite of what the faculty writes:

It may be … advisable to acknowledge the fact that there is another “psychoanalysis” besides the Freudian science of psychoanalysis, which really wants to be a worldview [Weltanschauung]. From this recognition, perhaps the possibility of a more effective refutation or combat [against this Weltanschauung] arises. For, to be frank, the “Weltanschauung Psychoanalysis” is an unsympathetic and dangerous thing from which the circle of psychoanalytic educators may remain protected as far as possible! (Bernfeld Reference Bernfeld1928, 201)

Bernfeld’s attempt to emphasize the scientific nature of his approach and thus gain access to university science was bound to fail. It may not have helped his case that he—in the same essay of 1928—had slightly attacked Eduard Spranger (1882-1963), who would then prove to be his main opponent at the Faculty of Philosophy in Berlin. Tactically not very cleverly, Bernfeld imputed to Spranger and other psychologists a “non-scientific background” for their attacks on psychoanalysis (Bernfeld Reference Bernfeld1928, 203).

The faculty files contain a draft of the final faculty opinion from 25 June, 1931, about Bernfeld’s application, which had been discussed on a faculty meeting on 11 June. In the more general part, drafted by Spranger and the philosopher Max Dessoir (1867-1947)Footnote 36 and dealing with psychoanalysis as such, is the following passage, which was left out of the faculty’s letter to the ministry later:

The Faculty is not able to recognize that psychoanalysis in its psychological, cultural-philosophical and pedagogical parts is a science in the strict sense. According to Prof. Freud’s expression it should be “above all the art of interpretation.” In fact, it has become an industry of interpretation which, under the brand “scientific discovery,” produces masses of myths and offensive puns. It evades scrutiny in two ways. On the one hand, its procedure is such that it always remains in the right: if, for example, a dreamer admits a certain symbolic interpretation, everything is fine; if he resists it, he proves that the interpretation was correct precisely through this “resistance.” The other deviation from the law of science lies in the dogma that access to the truths of psychoanalysis can only be gained through one’s own analysis, because this is a kind of initiation, an act of admission into an esoteric circle, but not a teachable condition of knowledge and insight for objective research.Footnote 37

Parts of this are reminiscent of Karl Popper’s later verdict upon psychoanalysis as not being scientific because it is not falsifiable.

The other, more physics-related part of the original faculty opinion had been drafted by the eminent Berlin Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967). Here one reads:

In his writings, published jointly with Feitelberg and summarized under the title “Energy and Drive,” Bernfeld attempts to relate essential features of Freud’s drive theory to the concept of physical energetics. Insofar as these essays contain a rendition of general physical theorems in close connection with the formulations of experts, they are correct. As soon as Bernfeld begins to apply the laws of physics to biological and psychological problems, it becomes apparent that there is not even the slightest understanding of the basic physical concepts and clarity of thought that is absolutely necessary for the task undertaken. One misinterpretation of the physical theorems follows the other, the very vaguely understood concepts of theoretical physics flow into each other in the worst possible way, and similarities on the very surface immediately lead to the identification of physical, biological and psychological facts. Never could a procedure have been more rightly called dilettantism in the worst sense of the word than this frivolous and confused undertaking. The boldness of the undertaking and the vastness of the intended theory-building would be welcome in itself. But if the conscientiousness and rigor of thought is completely lost, such products will separate themselves from everything that deserves the name of science. Nothing worse could happen to students in their scientific and personal development than to be influenced by such an example of vagueness and frivolousness.”Footnote 38

Bernfeld, in a book written in collaboration with the engineer, physicist and physician Sergei Feitelberg (1905-1967), had tried to find bridges between physics and psychology based on Wilhelm Ostwald’s “energetics” (Bernfeld & Feitelberg Reference Bernfeld and Feitelberg1930). The two authors assumed the “Existence of psychic energies, which enable the work performance of the psychic apparatus” (ibid, 3). They tried to connect to “Köhler’s important use of the concept of system in psychology” (ibid, 5) but also realized Köhler’s reservations:

Köhler has discussed in detail the very interesting fact that in physics electric and magnetic fields possess Gestalt properties. Together with Wertheimer, he showed the importance of psychical gestalten [psychische Gestalten]. A connection between these two phenomena is not attempted or rejected. On the basis of the energetic view that we hold here, such a connection arises as a necessary consequence of the concept of personalized energy [personierte Energie].” (Bernfeld & Feitelberg Reference Bernfeld and Feitelberg1930, 37)

Köhler confirmed his reservations by the scathing verdict noted above. But why would the faculty not send this original draft to the ministry?

Although RvM was not a member of the faculty commission dealing with Bernfeld’s application, and although he is mentioned only marginally by Tenorth in his essay (Tenorth Reference Tenorth1999, 304, 306), he was a member of the faculty and participated in the final formulation of the statement against Bernfeld. However, he did this in a somewhat mitigating and conciliatory manner.Footnote 39 This is documented by the protocol of the faculty meeting on 11 June 1931, which says, among other things, the following about the draft: “V. Mises finds the general criticism of psychoanalysis too sharp. In the physical questions, the negative judgment of Bernfeld seems too harsh to him as well. The faculty decides that Mr. Köhler and v. Mises should reformulate the sentences relating to physics.”Footnote 40

The next step towards reformulating the faculty opinion is mentioned in a hitherto unknown letter written by Köhler to RvM on 13 June. According to this letter, Köhler now preferred to leave the task of finding the right formulation for the scientific part to RvM.

An English translation of Köhler’s letter in figure 5 reads:

Psychological Institute of the University Berlin C2, Schloss (Castle), 13 June 1931

Esteemed colleague,

May I make a suggestion? I am thoroughly tired of the extensive occupation with Mr. Bernfeld’s work. However, when we soon sit down together to turn the judgement I have proposed on his physical-biological writings into a wording that seems to you to be more just than the previous one, it will again take a lot of time. I am convinced that we will reach our goal much more quickly if you yourself write down and bring along a few sentences in advance which reflect your opinion and could be included in the larger document.

I am sure that you too will save time in this procedure. And since you agree with the rest of us on the main point, namely the negative assessment, it is hardly to be expected that your wording will be subject to a lot of requests for changes. I also admit that my criticism contained too many extreme expressions in dense accumulation. I myself had such a feeling when colleague Spranger read out the wording. Admittedly, this does not mean that my position on the matter has changed. You yourself will not have the impression that Bernfeld, where Mr. Feitelberg apparently let him operate alone, reveals even remotely sufficient insight into the content of the Second Law [of Thermodynamics; RS].

With sincere admiration and best regards

Your very devoted

Wolfgang Köhler

Eventually, based on RvM’s reformulation, the physics-related part of the negative faculty opinion of June 25, 1931 read:

In Professor Freud’s letter, special reference is made to Bernfeld’s more recent work, in which he attempts to tackle questions of psychoanalysis with the means of exact science. The Faculty has examined the works published by Bernfeld and Feitelberg (Energy and Drive 1930) and is unable to recognize in them a valuable scientific achievement. The physical foundations on which the authors build are inadequate in every sense; in the first of their treatises they start from a physical principle that was occasionally stated in the 1880s, but has since long been recognized as inapplicable by all physicists. The further explanations are based on the classical laws of thermodynamics which are reproduced in an undefined and vague form and try to draw conclusions from them for the evaluation of psychic processes. It is explicitly emphasized that measurement methods for the variables that come into question in mental processes cannot be given. But since those thermodynamic laws, like all theorems of physics, contain essentially quantitative statements, they become completely meaningless as soon as they are transferred to series of phenomena that are inaccessible to measurement. Therefore, all the conclusions drawn by the authors are unfounded, and if these conclusions take a form by which they seem to support certain claims of psychoanalysis, this can only be explained by the tendency of the authors, which is fixed from the outset, and which is not aimed at an objective test, but exclusively at a confirmation of the doctrine which is dogmatically accepted.”Footnote 41

Figure 1. Excerpt from the letter from Sigmund Freud to Heinrich Löwy (and by implication Richard von Mises) which is online at https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39990.03643/?sp=2 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Sigmund Freud Papers, box 36, folder 43.

Figure 2. The letter by Richard von Mises for the Freud Papers is online at https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39990.03643/?sp=7 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Sigmund Freud Papers, box 36, folder 43.

Figure 3. Richard von Mises’ family in Vienna, ca. 1894. From the left: his older brother Ludwig (later a famous economist), his father Arthur, RvM, Adele, and to the right his younger brother Karl, who died early in 1899. Courtesy Harvard University Archives, HUG 4574.92 p.

Figure 4. Hilda Geiringer (1893-1973) – private possession Magda Tisza (Boston).

Figure 5. Letter by Wolfgang Köhler to Richard von Mises. Courtesy Harvard University Archives, HUG 4574.5. Box 2, Folder 1931.

Figure 6. The postcard (front and reverse) from Sigmund Freud to Karl Kraus is accessible online at https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39990.03540/?sp=2 and the following page. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Sigmund Freud Papers, box 35, folder 40.

Figure 7. John von Neumann (front left), Richard von Mises (second), and George Taylor (third from left) received honorary doctorates from the University of Istanbul on the occasion of the International Congress for Applied Mechanics in April 1952, one year before the Interview. Courtesy Harvard University Archives. HUG 4574.90P.

Figure 8. Nathansohn and Kallir family trees (only selected lines leading to Freud, to Richard von Mises, and to John and Jane Kallir). Produced by the author.

By the “physical principle that was occasionally stated in the 1880s,” RvM meant a principle set forth by the French chemist Henry Louis Le Chatelier (1850-1936).Footnote 42 The principle is based on chemical equilibrium and has been extended into economic theory. Le Chatelier’s principle can also be used in describing mechanical systems in that a system put under stress will respond in such a way as to reduce or minimize that stress. But RvM was at the time skeptical vis-à-vis the use of the principle in physics, let alone psychology. As to the principles of “energetics” assumed by Bernfeld and Feitelberg, the relation of the laws of thermodynamics to them is a topic that is still under debate today.

The discussion about Bernfeld’s teaching position took place in the immediate run-up to RvM’s election as Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy (which included mathematics, the sciences and psychology, but also history and philosophy) for the academic year 1931/32. Entrusting RvM with the final formulation of the faculty statement should be interpreted as a kind of “test” for RvM, shortly before his election on 16 July 1931.Footnote 43 As Köhler says, RvM agreed “with the rest of us on the main point, namely the negative assessment.” As a mathematician and physicist, RvM argued against the recognition of psychoanalysis as a science, despite a positive evaluation by Freud and despite personal ties to Vienna. Thus, the faculty could be reasonably assured that RvM, this incredibly energetic Austrian of Jewish origin, would not “betray” the German ideals of science and, on the other hand, would take over the unpleasant administrative tasks of a dean to general satisfaction.

One wonders whether the decision of the faculty would have been different if Kurt Lewin (1890-1947),Footnote 44 the other noted Gestalt theorist besides Köhler at the Berlin institute for psychology, had been involved (he was only associate professor and therefore without a vote). He was known to be more open to psychoanalysis than Köhler and appreciated parts of Bernfeld’s work (Ash Reference Ash1995, 267). Dudek describes how Bernfeld, in the early 1930s, tried to connect to Lewin, until the latter left for Stanford (US) in May 1932 (Dudek Reference Dudek2012, 506–507). In his paper “Die Gestalttheorie,” Bernfeld appealed to both Lewin and Köhler for cooperation, in particular for finding “a path from qualitative to quantitative research” (Bernfeld Reference Bernfeld1934, 76).

Beyond the Berlin Philosophical Faculty, the attempt by Bernfeld and Feitelberg to create a bridge between the Second Law of Thermodynamics and the death drive (or the opposing libido) via the notion of entropy was very critically discussed by both psychoanalysts and physicists.Footnote 45 However, as described by Dudek (Reference Dudek2012, 492), this effort for “libidometry,” which was partly based on animal experiments, found vivid interest among some members of the Vienna Circle of Logical Empiricism and the Unified Science Movement, which led to contact between Bernfeld and Otto Neurath, and later also Hans Reichenbach.Footnote 46

It is interesting to note that the name of Sergei Feitelberg also appears in the 1953 Interview (49–51). There is, however, not a word in the Interview about the Berlin affair of 1931. Although Feitelberg was recognized as a pioneer in the use or radioisotopes in clinical medicine, RvM and Geiringer vividly recall what they view as Bernfeld and Feitelberg’s incompetent use, around 1930, of physical and mathematical arguments to justify psychoanalysis: their acceptance of Freudian theory ended exactly at the point where their own expertise as scientists was at stake. Indirectly, the fact that RvM sided with the Berlin faculty in the decision against Bernfeld seems to confirm a certain outsider position in the Vienna Circle (Stadler Reference Stadler2015), in whose famous Manifesto of 1929 he is not even mentioned among scholars “close to the Circle” (Verein Ernst Mach 1929). RvM’s notion of “unified science” differed considerably from the one promoted in the Circle; RvM’s insistence on “connectibility” in his own epistemological work (Mises Reference Mises1951) went in a rather different, specific direction which still awaits detailed analysis.

2.3. Richard von Mises’ statistical epistemology of psychoanalysis

2.3.1. Richard von Mises’ interpretation of dreams

Two passages of the Interview in which RvM and Eissler reflect on the posthumous reputation of Freud and of psychoanalysis have been quoted above. I now quote the second one in a broader context, this time with the passage of the Interview that deals more precisely with the interpretation of dreams (36–37):

RvM: Well, I am not a 100% fan of psychoanalysis, but of Freud I am. /laughs/ He is a great man after all, right? Do you think Freud as a personality will lose interest?

Eissler: I do not think so, otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this job. Because I think that he might be very important for a very specific reason, because he was actually the first person who was able to analyze himself, which was to some extent against human nature. And I don’t think one has any idea why it was possible for him to do that. …

RvM: Yes, I find his dreams that way, not his small Traumdeutung [Interpretation of Dreams], but the thick volume, that contains his dreams.

Eissler: Yes

RvM: I find that so amazing!

Eissler: That was surely his greatest work. To be able to do this was a very great deed. And I don’t think that anyone today has any idea how such a thing was possible. It was actually a reversal of the whole energetic process in humans [Umkehrung des ganzen energetischen Ablaufes im Menschen].

Apart from the fact that RvM here apparently confuses the more popular and shorter book About Dreams (Über den Traum) from 1901 with the earlier and more detailed Interpretation of Dreams (Traumdeutung) from 1900,Footnote 47 which he describes as “the thick volume,” the passage clearly shows that RvM was quite intensively engaged in reading the Interpretation of Dreams.

In RvM’s estate at Harvard University Archives there is a folder entitled “Theory of Dream,” which contains nine pages of handwritten German notes about RvM’s own dreams and interpretations. As an “example of a dream with identification, 27 XI.1943,”Footnote 48 RvM tells of a “perceptive” (scharfsinnig) mathematical discussion with his motherFootnote 49 in her Vienna apartment which was “in some unspeakable way”Footnote 50 connected with an operation which his mother performed on the mathematician Eduard Helly (1884-1943), who was stretched out diagonally on the dining table and wrapped in a linen cloth: “It turns out to be completely natural that Dr. H. is dead at the last step.”Footnote 51

In the same folder follows a printed notice of Helly’s death on November 28, 1943, one day after the dream. Whether RvM interpreted his dream as a premonition of Helly’s death, or whether RvM had been informed long before about an illness of his Viennese friend, who had also been forced into American emigration, is unknown.

One of RvM’s handwritten notes in the same folder says the following: “The psychoanalytical interpretation of dreams can only be understood as a statistical law. Childhood experiences or other repressions determine an inclination to certain dreams. – Certain dreams are more common in people with certain waking experiences of the past” (emphasis in original).Footnote 52

2.3.2. Richard von Mises’ philosophical reflections on psychoanalysisFootnote 53

In 1959, Geiringer, who was by then RvM’s widow, wrote about him: “He interpreted everyday things instinctively in scientific terms. Statistics played a very great role in his scientific conception of the world. (Many discussions with Einstein who said: ‘Gott würfelt nicht.’) Mises saw in the statistical conceptions a great progress towards unification.”Footnote 54 This attitude apparently also determined RvM’s relationship to psychoanalysis, as indicated above. There are similar remarks in RvM’s Kleines Lehrbuch des Positivismus (1939), which came out in 1951 in English translation as Positivism (Mises Reference Mises1951) and provoked numerous, often rather contradicting reviews, mostly by philosophers.

In 1951 the psychologist (not strictly psychoanalyst) Abraham A. Roback (1890-1965), who is mentioned in the Interview (34), published a review of RvM’s philosophical book on Positivism (Mises Reference Mises1951) in the New York German-American weekly Aufbau (21 December 1951, 7–8). There he says: “He favors psychoanalysis to the extent that he supposes it is confirmed by statistical correlation. But that is just what academic psychologists would like to see” (8).Footnote 55 In the reviewed book itself, Mises begins by saying:

On the border line between psychology and psychopathology stands psychoanalysis, a creation of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). It comprises a scientific theory of a specific area of psychological phenomena and a technique for the treatment of certain illnesses derived from the theory. … The effective content of the unconscious is primarily formed by “repressions” which originate in most cases in the conflict between sexual drives and external circumstances. By making the repressed experiences conscious again, they may be deprived in part of their harmful influence. (Mises Reference Mises1951, 238)

In his philosophical effort to demonstrate the “connectibility” of physical, biological and spiritual phenomena, RvM then says: “Nobody will deny that every experience leaves in the experiencing subject, … an ‘engram,’ which may remain latent for a long time and become effective again later on. That does not constitute a contrast between living and dead matter, to which modern physics also assigns a kind of a memory” (Mises Reference Mises1951, 238).

Finally, RvM discusses his statistical interpretation of psychoanalysis:

Possibly, from a logical point of view, the objection could be raised that, instead of the concept of strict causality, a statistical relation should be applied to the interdependencies indicated by psychoanalysis—perhaps in the sense that persons under the influence of certain engrams are more inclined toward certain Freudian slips, nervous symptoms, and dream pictures than others who are free of them, just as a die that has been tampered with shows more sixes on the average than an unbiased one. The entire field of phenomena like dream images, slips, etc., seems much more similar to the type of recurrent events (Chapter 14, 1 [referring to his own book]) with which the calculus of probability is concerned, than to that type of physical events which led to the concept of causality (Chapter 13). It is a reasonable conjecture that psychoanalytic theory would have received a more correct form, modified in this sense, if at the time of its creation the deterministic conception of all natural occurrences had not been so absolutely predominant in science and if, instead, the concept of the collective as discussed in Chapter 14, 3 had been generally better known.

Psychoanalysis comprises the scientific theory of a specific area of psychological occurrences: on the grounds of uncontestable observations it constructs a causal connection between certain symptoms and the latent remainders of earlier experiences. Almost all objections raised against it so far are of an extra-logical nature. But it seems justified to point out that the totality of the observations in this field seems to correspond more to the assumption of a statistical than of a strictly causal correlation. (Mises Reference Mises1951, 238)

Earlier in the century, RvM had tried to re-interpret fluid dynamics and the famous Navier-Stokes equations in terms of statistical concepts (Siegmund-Schultze Reference Siegmund-Schultze2018). With the “concept of the collective,” RvM refers in his book to his own theory and to his foundations of probability and statistics. The latter foundations were highly controversial, and not only among his American colleagues. RvM’s theory experienced a certain renaissance in the 1960s in the context of A.N. Kolmogorov’s algorithmic complexity theory (Siegmund-Schultze Reference Siegmund-Schultze2004).

A manuscript in English from May 1953, shortly before the Interview, entitled “The Role of Positivism in the XX Century,” which Hilda Geiringer published in 1964 in the second volume of her husband’s Selected Papers, states:

First, in the sixteenth century the overthrow of the geocentric conception of the world by Copernicus, then in the first half of the nineteenth century the appearance of those ideas which are associated with the name of Darwinism, and finally in our time the theory of psychoanalysis. These are three steps in the coming of age of mankind. As we shall see, positivism in general is another such step. …

If such things must be stated in connection with a scientific doctrine of well over one hundred years standing [Darwinism], no one will expect that a more satisfactory picture can be drawn in the case of modern psychoanalysis, my third example. One of the revolutionary ideas of psychoanalysis is to establish an interconnection between certain bodily characteristics of man and the loftiest products of the human mind, art, scientific invention, and religion. It is true that some aspects of psychoanalytic practice are fashionable to-day—I would say too much so—and enjoy a similar popularity and a trend towards exaggeration as did the theory of evolution two generations ago. But this refers to a limited circle of half-intellectuals who only appreciate conspicuous innovations without realizing their last consequences.

During the past year [i.e. 1952, RS], some official approbation, full of reservations, has been given by the Church authority. Now, the way is open to the typical development: the gradual absorption of the fundamentals of the theory into the body of established science, accompanied by the never ceasing latent opposition of Church and state authorities, of the general public, and of all those who in books, magazines and newspapers cater to the taste of the public. (Mises 1953, 537–539)

Compared to 1931, when he did not recognize psychoanalysis as a science, in compliance with the dominant mood in the Faculty of Philosophy in Berlin, RvM—having emigrated to a new, American environment—had apparently changed his mind. By describing psychoanalysis as one of four “steps in the coming of age of mankind,” along with Copernicanism, Darwinism, and Positivism, which he himself advocated, RvM was paying the maximum possible tribute to the theory of his fellow countryman Freud.

3. New insights into the relationship between Freud and Karl Kraus based on the 1953 Interview and on a recently rediscovered letter by Kraus from September 1906

The relationship between Freud and Karl Kraus (1874-1936), two prominent figures of Viennese intellectual life in the first decades of the twentieth century, is addressed several times in the Interview. Freud, like almost all intellectuals in Vienna, was a reader of the Fackel, which did not necessarily mean that he agreed with the views of Kraus, who often filled the entire journal with his own contributions. RvM says at one point of the Interview: “I have the entire Fackel” (25). And he had said before: “Freud had a somewhat strange relationship with Karl Kraus” (19). Based on postcards from Freud to Kraus in his possession, RvM says repeatedly that “He used Karl Kraus as a journalist” (20, 26). In another passage, RvM responds to a remark made by his wife (26):

Geiringer: Yes, but also Kraus [thought highly] of Freud.

RvM: No, I don’t know, Kraus is not such an easy thing [einfache Sache]. Kraus made tremendous jokes about him, about psychoanalysis.

RvM says finally: “Kraus later became a great mocker of psychoanalysis” (26). However, this later relationship between Freud and Kraus is not discussed in the Interview. The Interview is only about their relationship in the years 1904-1906, when Freud and Kraus got to know each other for the first time.

In the course of the Interview, RvM showed Eissler four postcards from Freud to Kraus that were in his possession at the time. One was from July 1904, and the other three from October 1906. Like Kraus, RvM was an autograph collector, and had acquired these four postcards from Kraus’ estate after his death in 1936, as the Interview reveals (29). They later came into the possession of a friend of the Mises Couple,Footnote 56 the psychoanalyst Grete L. Bibring (1899-1977),Footnote 57 who, in 1961, became the first female professor at Harvard Medical School. Bibring gave the cards to the Freud Papers in December 1976, where they are now located and have been available for researchers since 2000.

3.1. Freud, Kraus, and the Hervay Affair

While the three postcards of October 1906 are related to the so-called Fließ Affair (see below), Freud wrote the first one, from July 8, 1904, spontaneously and apparently without a concrete purpose: “A reader who cannot be your follower very often, congratulates you on the insight, the courage and the ability to recognize the great in the small that your article on Hervay reveals” (see figure 6). Kraus himself quoted this postcard with correct wording much later, on June 19, 1908, in a polemical article against Maximilian Harden in Die Fackel.Footnote 58 In this article, Kraus does not give a date for Freud’s postcard, but adds that Freud and he were not personally acquainted with each other at the time.

This July 1904 postcard from Freud to Kraus, which marks the first contact between the two, has been connected to the so-called Hervay affair by Edward Timms, though based on vague sources and with incorrect date.Footnote 59 I therefore publish it here in facsimile, which gives the exact date as July 8.

Freud reacts here to an article by Kraus published on the same day in Die Fackel. The background to Kraus’ article and to Freud’s reaction of the same day was the Hervay Affair, which at the time caused a great stir but is hardly known today. It was briefly discussed in Timms (Reference Timms1986, 64-67) and has been thoroughly described and analyzed in Alison Rose’s book Antisemitism, Gender Bias, and the ‘Hervay Affair’ of 1904: Bigotry in the Austrian Alps (Rose Reference Rose2016). Since the Interview provides some additional information about the affair below, I provide here just a few general remarks, based on Rose’s book.

In 1904, Leontine von Hervay (1860-after 1930), newlywed wife of the district governor (Bezirkshauptmann) of Mürzzuschlag, a small resort town in Styria halfway between Vienna and Graz, was arrested, tried, and convicted of bigamy and false registration. Her rather unusual family history as the immigrant, repeatedly divorced daughter of a magician with a non-Catholic (allegedly Jewish) background, the fact that she was twelve years older than her new husband Franz von Hervay, and envy of the latter’s rapid rise to the office of district governor at the age of only thirty-two, all led to a hounding of the unequal couple, which ultimately drove Hervay to suicide. After his death, his widow received a disproportionately severe punishment for the minor formal errors and inaccurate information she gave when she married, even compared to the legal norms of the time. In the end, the Hervay family enriched itself with the personal property of the accused widow. According to Rose, Franz’s brother Karl von Hervay, whom RvM knew “very well” from his time in the Austrian army during the World War (Interview, 23), played a particularly inglorious role in the affair.

For the Austrian satirical writer and journalist, Karl Kraus, the “Hervay Affair” highlighted sexual hypocrisy and antisemitism, while the anti-Semitic press claimed the affair illustrated Jewish criminal behavior and the corruption of the Jewish press (Kraus Reference Kraus1904).

As noted above, of the three participants in the Interview, only RvM was of an age to personally remember the Hervay Affair. RvM’s choice of the word “demi monde” (23) in the Interview may reflect his petty bourgeois resentment against Mrs. Hervay. His refusal to address the anti-Semitic aspect of the affair is not untypical of his behavior at other times in his life, when he did not mention this topic despite having experienced discrimination himself. In any case, in the Interview RvM also shows compassion for the district governor’s wife. Given the political situation at the time, RvM’s use of the word “witch Prozess” would not have been accidental, especially for a resident of Cambridge, near Boston, such as RvM. In January 1953, Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, which was widely regarded as a parable for the “Red Scare” conjured up by Senator Joe McCarthy, premiered in Boston. In Salem, a suburb of Boston, the original witch trial had taken place in 1692, which inspired Miller’s play and led to the politically even more explicit French-East German film in 1957, based on a screenplay by Jean-Paul Sartre. In any case, RvM’s following remark in the Interview about Freud’s postcard of July 8, 1904, where he refers to Kraus’ article in the Fackel “Der Fall Hervay” (1904) of the same day, seems justified: “Kraus has taken care of her [Hervay’s wife]. And so this seems to be a spontaneous statement from Freud in favor of Hervay’s wife” (25)

3.2. Freud, Kraus, and the Fließ Affair

The three other postcards from Freud to Kraus that were in RvM’s possession at the time of the Interview are, as mentioned, related to the Fließ Affair, and have the following dates:

-

October 2, 1906: Freud’s suggestion to Kraus to meet at Café Landtmann.

-

October 7, 1906: Freud alerting Kraus to an article by Magnus Hirschfeld in Wiener Klinische Rundschau, no. 38 about the Fließ Affair.

-

October 31, 1906: Freud thanking Kraus for his “dismissive treatment” („wegwerfende Behandlung“) of Fließ’ protestations in Kraus’ article (1906) in Fackel of the same day.

These three postcards have already been mentioned by Szasz ([1976] Reference Szasz1990), Worbs (Reference Worbs1983), and Timms (Reference Timms1986), and have been partially cited by them from then still uncertain sources (auction catalogs), while Schröter (Reference Schröter2002, Reference Schröter2003) has interpreted the postcards in more detail, based on these citations.Footnote 60 The postcards were made available to researchers by the Freud Archive in 2000.Footnote 61

With respect to the “Fließ Affair,” which has been repeatedly discussed in the Freud literature and briefly alluded to in the introduction above, the specialists essentially agree that Fließ and his supporter Richard PfennigFootnote 62 exceeded every reasonable measure in their public statements against Freud. However, there is also agreement that Freud himself was somewhat careless in passing on Fließ’ ideas about bisexuality to Otto Weininger, who used them in 1903 for his much-discussed book Geschlecht und Charakter (Sex and Character) without mentioning Fließ.Footnote 63

In 1961, Freud’s son Ernst published a letter from Freud to Kraus dated January 12, 1906, in English translation (Freud Reference Freud1961, 259–60). After informing Kraus about the campaign by Fließ and Pfennig against him, Freud says in his letter: “I trust it is not necessary for me to defend myself in detail against such absurd slander.” Alluding to the involvement of Weininger in the affair Freud then adds: “I personally do not share the high esteem for Weininger as expressed in the Fackel. But in this case I feel obliged to side with Weininger’s friends.” In the same January 1906 letter, however, Freud utters a warning against one-sided support for the deceased Weininger: “The undoubtedly brilliant young man cannot be spared the reproach of having failed to divulge the source of this idea and, instead, of passing it off as his own inspiration.” Freud ends his letter to Kraus with the following words: “Please consider these lines as a private communication, and rest assured that I shall be at your disposal at any time with comments suitable for publication.”Footnote 64

Because Kraus would eventually, in his short article in the Fackel of 31 October (Kraus Reference Kraus1906), side with Freud in the Fließ Affair, Freud’s letter from January 1906 has been repeatedly interpreted as evidence for Freud’s instrumentalization of Kraus for his purposes. According to the 1953 Interview, RvM, too, had gained the same impression from the three 1906 postcards in his possession, although he apparently did not know of the January 1906 letter. However, in a more nuanced historical analysis, Schröter (Reference Schröter2002, Reference Schröter2003) has pointed to Kraus’ own interest in an exoneration of Weininger, whom, as Freud remarked in his letter, he had repeatedly supported in the Fackel before.

Further evidence for Kraus’ own vested interest in the Fließ Affair comes from a letter which Kraus wrote to Freud on September 16, 1906.Footnote 65 This letter has to my knowledge not been mentioned anywhere in the Freud or Kraus literature, let alone published. Kraus says first, in obvious allusion to the final remarks in Freud’s letter of 12 January: “You, esteemed Sir, addressed a letter to me in this matter at the time, but you did not consider the publication of it appropriate.” Kraus continues in his letter of September 16:

Mr. Swoboda asked me almost simultaneously not to take any notice of the affair until the publication of his justification paper. Now it seems to me—especially after the vehement “self-advertisement” [Selbstanzeige] of Mr. Fließ in Harden’s The Future [Die Zukunft]—that a statement of the Fackel is necessary. I myself, who have dealt far too little with the actual object of the dispute, unfortunately cannot take the floor…. That is why I would like to ask you, esteemed Professor, to finally clarify the matter as the most competent person. I am extremely grateful to you if you would like to send me a letter—also for your own protection against the arrogations [Arrogationen] of Herr Fließ—which could be as long or as short as you wish.

Kraus thus explains a previous absence of polemics against Fließ in the Fackel with a wish of Swoboda,Footnote 66 the patient of Freud, who, according to the unanimous opinion of all commentators today, was wrongly accused by Fließ of having plagiarized his theory of biological periods (see below section 4). Kraus does not claim that Freud had asked him not (!) to polemicize against Fließ on principle. Indeed, Freud’s offer to “be at your disposal at any time with comments suitable for publication” (see above) seems to point to the opposite.Footnote 67 It seems to me that Freud was primarily interested in having an effective publication against Fließ in the Fackel, one which should not be implausible from the outset—by concealing Weininger’s improper behavior in this matter.

What is striking about Kraus’ letter of September 1906 is that Kraus admits that a publication in the weekly magazine Die Zukunft (Fließ Reference Fließ1906b) had provoked him to attack Fließ. This can certainly not be understood independently of Kraus’s longstanding polemical dispute with Maximilian HardenFootnote 68 in Berlin. Thus, the entire affair was probably about a double front position of Kraus vs. Harden and Freud vs. Fließ, and in both cases the resentment of the Austrians, Freud and Kraus, against the self-righteous German “Piefkes” (slang for Prussians) Fließ and Pfennig probably played a role. Also remarkable about the September letter is that Kraus clearly admits his lack of competence in the scientific question of bisexuality.

The next archival evidence of a reaction is a letter from Freud to Kraus nine days later, on September 25, 1906.Footnote 69 Without directly referring to Kraus’ letter of September 16, Freud says there: “The miserable Fließ affair should bring the one thing I desire, that I am able to make your personal acquaintance.” He then asks Kraus to indicate a possible meeting place. The postcard from October 2, 1906 in RvM’s former possession,Footnote 70 in which Freud invites Kraus to Café Landtmann, is then apparently only the next step in the preparation of the meeting.Footnote 71

An evaluation of the contact between Freud and Kraus in the Fließ Affair cannot, of course, be made without a look at the result, namely Kraus’ publication in the Fackel on October 31, 1906, entitled “Bisexueller” (Kraus Reference Kraus1906).Footnote 72 Here Kraus considers it necessary, first of all, to trivialize the affair and to discredit the value of the object of dispute, Fließ’ theory of bisexuality, with the following remark: “In a meeting of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee [Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee] in Berlin, it was pointed out, as the monthly report of February 1, 1906, says, that the idea of the double sex of humans had already been clearly expressed by Plato, for which the Berlin scholar Fliess now claims priority” (Kraus Reference Kraus1906).Footnote 73

In the second part of his short article, Kraus quotes from two letters that Freud had written to the prominent Berlin sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935), who had also been attacked by Fließ and Pfennig for his work on bisexuality. Freud had apparently explicitly permitted Hirschfeld to publish these letters directed against Fließ in his Monthly Reports (Monatsberichte). Thus Freud, by indirectly contributing to the polemics in a more scientific outlet such as the Monthly Reports, was by no means concerned with preventing publications against Fließ. One can probably also assume that it was Freud himself who drew Kraus’ attention to this article and thus to his letters to Hirschfeld. It is possible that Freud gave him a copy during the meeting at Café Landtmann. However, Kraus did not use Hirschfeld’s article in the Vienna Clinical Journal (Wiener Klinische Rundschau) about which Freud had informed him after the meeting in a postcard dated October 7, 1906.Footnote 74 This article would apparently have been too detailed and too scientific for Kraus’ purposes. Again, Kraus was above all interested in a statement from the master himself, from Freud. Freud, on the other hand, did not want to “defend himself in detail against such absurd slander” (as quoted above), and even less did he want to appear as a “journalist” himself in a magazine like the Fackel with a broad readership, especially in his hometown Vienna.Footnote 75

Kraus’ article “Bisexueller” of October 31 (Kraus Reference Kraus1906), which was partially quoted above, certainly underlines—among other things by the trivial reference to Plato—Kraus’ incompetence in the factual evaluation of the Fließ affair. He himself had admitted this incompetence in his letter to Freud in September 1906. Thus, Freud’s reply card of the same day, which is quoted in Eissler’s Interview with the Mises Couple (20), can be understood in two ways: as thanks to Kraus and as a slight criticism of his superficial, unscientific journalism: “Dear Sir! Thank you, this matter certainly does not deserve anything other than such dismissive [wegwerfend] treatment.”Footnote 76 Apparently the two great Viennese instrumentalized each other for their own purposes in the Fließ Affair.

4. Richard von Mises’ interest in Wilhelm Fließ’ theories of bisexuality and biological periods

RvM himself seems to have been interested in theories of bisexuality in a psychoanalytical context. In the 1950s, he corresponded on the subject with the Viennese psychoanalyst Hitschmann (mentioned above in section 1), who, like RvM, had also sought refuge in the United States. In an undated letter to RvM from 1951/52, Hitschmann gives examples from his psychoanalytic practice. Among other things, the letter first alludes to a (not documented) mention by RvM of the notion of the hermaphrodite (Zwitter) and then continues: “We are all hermaphrodites, but the organs of the opposite sex are in us—rudimentary; but mentally it makes so many difficulties! One of the causes of neuroses!”Footnote 77

RvM was even more interested in Fließ’ second theory, which also played a role in the “priority dispute” with Freud, especially with regard to Freud’s patient and student Swoboda, the so-called period theory. This theory asserts that there are time intervals which are biologically important for individual human life. Fließ claimed that they can be represented in a simple way, measured in days as multiples of the period numbers 23 and 28. This theory was related to Fließ’ theory of bisexuality. The number 28 was associated with the female menstrual cycle, and the number 23 with a specific, empirically obtained male cycle,Footnote 78 and it was claimed that both cycles were to determine the life of each individual of both sexes in a specific way. Period theory was mentioned in the Interview even before the theory of bisexuality came up, with RvM only saying that Freud had probably never given it much thought (20–25).

However, other historical sources now show that RvM himself had a certain interest in Fließ’ periodic theory from the perspective of an applied mathematician. This—and the fact that prominent scientists and philosophers such as Wilhelm Ostwald (1853-1932) showed interest in the theory as well (see below)—may have led RvM to suspect (although this is not documented) that Fließ was treated unfairly by Freud and in reviews of his book on periodicity (Fließ Reference Fließ1906a). In all of RvM’s statements, however, one must bear in mind that he often loved to swim against the tide and to play the devil’s advocate, as he sometimes felt himself pushed into the position of an outsider (Siegmund-Schultze Reference Siegmund-Schultze2004).

Frank J. Sulloway gives in his Freud—Biologist of the Mind (1979) the following damning verdict of the mathematics in Fließ’ theory of periodicity:

As for Fliess’s claim to have turned biology into a natural, mathematical science, Martin Gardner—otherwise known for his monthly Scientific American column “Mathematical Games,” as well as for his delightful book Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957)—has delivered the last and perhaps the most damaging blow to Fliess’s “Teutonic crackpottery.” Fliess, Gardner explains (1966), analyzed all his periodicity data in terms of the general formula x • 23 ± y • 28. Unfortunately Fliess’s mathematical abilities must have been limited to elementary arithmetic, Gardner asserts, for what Fliess did not seem to realize was that any two positive integers that possess, like 23 and 28, no common divisor, can be used with his general formula x • 23 ± y • 28 to derive any positive number whatsoever. Thus, there was no positive integer that Fliess’s formula could not produce, given the right juggling of the values of x and y. (Sulloway Reference Sulloway1979, 142)

Sulloway and Gardner, on whom he relies, cannot possibly have read Fließ’ original works very attentively. In fact Fließ himself wrote in his 1907 reaction to first reviews of his book (Fließ Reference Fließ1906a):

Now every pupil [Schüler] knows that you can represent any number … in this way. Only if you are able to prove, that the coefficients [x] and [y] are not arbitrary values, but are in a transparent relation to each other, that a law of coefficients exists, only then the formula has a scientific justification. The author has dedicated a separate section of 73 pages (page 342 to page 415) to this fundamental question…. One will certainly later be amazed at the degree of elementary education of these “critics” of the twentieth century. (Fließ Reference Fließ1907, 121–22)

It seems that the “pupils” at the end of the twentieth century knew even less about the basics of number theory than those at the beginning, and that later critics such as Sulloway and Gardner did not take any more trouble with Fließ’ book than the earliest critics had after its publication in 1906.

In the journal ZAMM (Journal for Applied Mathematics and Mechanics), of which he was editor, RvM himself had complained about the same hasty judgement against Fließ’ period theory, and claimed that it was typical of widespread reservations against applied mathematics:Footnote 79