Introduction

In a 2014 speech at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium, Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasised the importance of China's relationship with the European Union (EU). He stated that despite cultural, societal, economic, and political differences, the two sides together account for ‘one tenth of the total area on Earth and one fourth of the world's population’ in addition to ‘one third of the global economy’, suggesting great potential for Sino-EUropean cooperation.Footnote 1 President Xi's assertion about the significance of the EU-China partnership was repeated in ‘China's Second Policy Paper on the EU’, according to which the two partners ‘promoted [an] all-dimensional, multi-tiered and wide-ranging cooperation to deepen the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’.Footnote 2

Since President Xi's last visit to the EU, EU-China relations have continued to evolve, becoming more dynamic and sophisticated. The interactions between the two major global players reflect not only their priorities and concerns towards each other, but also key global trends of the past few years. All of these issues are much refracted in the rhetoric of the two partners. The EU updated its China strategy in 2016. In addition to old commitments and goals, the EU for the first time raised the issue of ‘reciprocity’ in EU-China relations, emphasising the importance of ‘a level playing field and fair competition across all areas of co-operation’.Footnote 3 In approval of this strategic paper, the Council of the EU further asserted its determination on ‘the constructive management of differences’.Footnote 4 In response to the EU's rhetoric, China issued its third EU policy paper in 2018. While acknowledging the EU's importance as a strategic partner in an increasing range of issues, China articulated in stronger language the demand that the EU respects its core interests, all concerning challenges to Chinese domestic affairs and state sovereignty, with explicit references to Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.Footnote 5

In view of their complicated relationship, the EU officially defines China in different ways across different policy areas: as ‘a cooperation partner’, ‘a negotiating partner’, ‘an economic competitor’, as well as ‘a systemic rival’.Footnote 6 Given this complexity, it is not surprising that the newly concluded Comprehensive Investment Agreement (CIA) immediately unleashed divergent feedback from both sides, even though it marks a milestone in EU-China relations. Despite heavy declarations from high-ranking officials, some Chinese policymakers still claim that the relationship with Europe is a second-order concern for Beijing.Footnote 7 On the other side, many European practitioners and politicians have expressed dismay over the ineffectiveness of the EU's long-standing efforts to work with China.Footnote 8

The belief that EU-China cooperation only exists in officials’ rhetoric ignores the expanding areas of Sino-EUropean cooperation. Contra views that envisage it as an insignificant matter, the article highlights the potential of EU-China relations as this is evidenced by the institutionalisation of the partnership and the ongoing policy implementation. The intradisciplinary literature on this relationshipFootnote 9 has not fully explored the possible sociopolitical implications for the final recipients of Sino-EUropean cooperation, that is, the citizens and in particular the citizens of China, who are most affected by the programmes and projects outlined in the partnership's framework.

To better understand this under-explored aspect of EU-China relations, we pose the following research questions. Does Sino-EUropean cooperation affect the lives of Chinese citizens and, if so, how is that possible and with what sociopolitical implications? We argue firstly that the collaboration between the two sides imposes a joint form of governmental power over the Chinese population, which becomes feasible due to the post-liberal governmentalisation of both the institutionalisation and policy implementation of Sino-EUropean cooperation. Second, under this post-liberal governmentalising political rationality, Beijing and Brussels, despite their differences on liberal questions of human rights, the rule of law and good governance, join forces for the sake of an effective and efficient management of the Chinese population. Third, this post-liberal application of governmental power results in empowered, yet not traditionally liberal political subjectivities for Chinese citizens.

The analysis follows Michel Foucault's epistemology and, more precisely, his governmentality approach.Footnote 10 Our analytical method complies with a threefold rationale. First, to primarily refer to the institutionalisation within the EU-China partnership to reveal the patterns of post-liberal political thinking that have made it possible for Sino-EUropean governmental power to flow over the Chinese population. Second, to show how policy implementation allows this flow of post-liberal governmental power, reified in concrete programmes and projects. Third, to identify the analytics of political subjectivisation associated with the specific application of Sino-EUropean governmental power.

Without an intention to generalise – we do not make the claim here that our discussion is applicable to all of the EU's external relations – our objective is to provide an alternative reading of EU-China relations that fundamentally departs from the focus on institutionalisation of the partnership, concentrating instead on the analytics and dynamics of governmentalised power relations flowing from the partnership. We demonstrate the governmentalised management of the Chinese population in the context of Sino-EUropean cooperation, fleshing out the underlying rationality and implications, that is, the political subjectivisation of the different sides involved in EU-China relations, particularly that of Chinese citizens. What is more, in contrast to the majority of scholarly voices focusing on how difference in norms and values hinders EU-China relations, we suggest here that such differences may not be as significant as argued and that issues often associated with liberal politics neither precondition the application of Sino-EUropean governmental power nor impede the social construction of certain political subjectivities for the EU, Chinese statesmanship, and the Chinese citizenry.

Our article is organised as follows. The first section briefly presents Foucault's approach to governmentality, accentuating how it can help us to understand the power relations flowing from Sino-EUropean cooperation. The second section analyses institutionalisation processes and policy implementation within the context of EU-China relations in order to illustrate the exercise of governmental power over the Chinese population and how this occurs according to a post-liberal political rationality. Empirical examples from the fields of environmental governance and disaster risk management are used to concretise our insights. The penultimate section discusses the political subjectivities that this post-liberal form of governmentality implicates for the EU, Chinese rulers, and citizens. The conclusion revisits the article's main points and paves the way for further problematisation in the study of EU-China relations.

Governmentality: One or many?

Foucault developed the governmentality approach in his lectures at Collège de France from the late 1970s until the early 1980s. The lectures capture his systematic effort to explain how and under which conditions human beings consent to being governed by other human beings. Foucault never explicitly defined governmental power but preferred instead to determine its distinct features. First, the mechanisms associated with the exercise of governmental power are ‘centrifugal’,Footnote 11 and therefore increase the coverage of exercised power over time. This is possible because governmental power is based on linkages and networks, which enable space, things, and human beings to be governed.Footnote 12 Second and associated with the previous point, governmental power regulates and manages the governed population.Footnote 13 As Joseph notes, this kind of power refers to a general, regulative form of governmentality, with the latter seen primarily as ‘the regulation of populations’.Footnote 14 Third, governmental power is complementary to disciplinary and sovereign forms of power but does not substitute for them. Compared to these other forms, it refers to a subtler and more economical exercise of power, one that depends on the unconscious consent of the population to be governed. As the French philosopher stated, ‘vis-à-vis government, [the population] is both aware of what it wants and unaware of what is being done to it’.Footnote 15 Fourth, governmental power has its own system of knowledge production. As Foucault explains, ‘Far from preventing knowledge, power produces it.’Footnote 16 This means that governmental power is ontologically dependent on certain technologies of knowledge and ‘regimes of truth’ – that is, power-laden, sociopolitical structures, discourses, and practices that dictate what is true and what is notFootnote 17 – that pave the way for its application. This echoes an understanding of governmentality as a specific form of political thinking and rationality that establishes the preconditions for the governance of human beings.Footnote 18 Fifth, the objectives of governmental power can be diverse, but they always aim to ensure the safety and survival of the population. Thus, Foucault talked about ‘tactics’ and not simply the ends of government.Footnote 19

How, then, is governmental power to be exercised over a population? Foucault opines that technologies of power are in place in order to guarantee the effective management of a population. More precisely, he recognises a generalised ‘apparatus (dispositif)’ to be applied by the government upon the ruled political subjects.Footnote 20 This apparatus of governance is hardly noticeable in society, and its abstract nature does not easily yield to empirical exploration. Nevertheless, it is endemic to governance practices, and Foucauldian scholars have often used this relatively concrete interface to examine the technologies of governmental power and inspect their application in the real world.Footnote 21

Governmentality can be defined in different ways: as the combination of the population, governmental power, and the apparatus allowing for its application; but also as the period in history in which the machinery of governance complements discipline and sovereignty without being a substitute for them.Footnote 22 A more simplified definition of governmentality describes it as ‘the conduct of conduct’.Footnote 23 Rose uses this definition to broadly associate the phenomenon of government with ‘the variety of ways of reflecting and acting which aim[ed] to shape, guide, manage or regulate the conduct of persons’.Footnote 24 Similarly, Death sees an analytics of government as a ‘framework’ that helps us ‘to comprehend all rationalised and calculated regimes of government, which conduct the conduct of (at least partially) free and multiple subjectivities through specific techniques and technologies, within particular fields of visibility’.Footnote 25 As we see, definitions of governmentality as ‘the conduct of conduct’ focus on the regulation and management of the governed population, which become feasible due to technologies of knowledge and regimes of truth that normalise the imposition of power. What is additionally apparent in such definitions is that there is a certain type of rationality, political and governmentalising, underpinning and enabling this imposition.Footnote 26

The logics of governing and being governed – the ‘mentalité’ in Foucault's ‘gouvernementalité’ – is central to the study of governmentality. For example, post-Foucauldian scholars focusing on liberal versions of governmentality emphasise the productive rationality that supports the exercise of governmental power.Footnote 27 In liberal governmentality, different liberties are, as Lemke observes, positively reinforced by the governing actors.Footnote 28 However, liberal governmentality entails a fundamental paradox; on the one hand, the governing actors encourage the population to be free, while on the other hand, they try to perpetuate their control over this same population.Footnote 29

Foucault himself was aware of this paradox when he addressed neoliberalism as a form of governmentality that attempts to resolve the conundrum of governmental power that both suppresses and enables political subjects.Footnote 30 He historically situates the rise of neoliberalism in the twentieth century and describes it as a system of governance and accompanying economic and political rationality centring on the regulation of political subjects’ lives, do so effectively and, most importantly, by economising the exercise of power as much as possible. In neoliberalism, the government imitates the market, regulating the lives of political subjects remotely. Joseph underscores this point: ‘neoliberalism … is a political discourse concerned with the governing of individuals from a distance’.Footnote 31 But how can the government's power in neoliberal governmentality be of such a light touch? Neoliberal practices of governance capitalise on the freedom of the political subject and transform it into a form of self-regulation that gradually becomes an employable skill and marketised value:

Neoliberal governmentality then is about the extension of the market vision of competition throughout the society, not just in the sphere of the economy. It involves the encouragement of the right ways of being free and rational: competition within the market is the ideal that actively molds the self-understanding, the desires, and the actions of the ‘free’ individual. Neoliberal governmentality refers then to the expansion of the market logic to all spheres of social life and its ‘mainstreaming’ into the psychology and social interactions of subjects.Footnote 32

Governmentality has inspired a critical reading of so-called advanced liberalism. As one of the first voices in this debate, Rose uses governmentality to examine the authority of expertise in liberalism.Footnote 33 In advanced liberal democracies, expertise is used to ‘depoliticise and technicise’ governance itself, normalising its various application technologies and thus minimising dissident voices that could jeopardise the effectiveness and efficiency of the established rule. In such a context, citizens are expected to claim ownership of their governance and self-regulate their behaviour so as to become ‘the self-actualizing and demanding subjects of an “advanced” liberal democracy’.Footnote 34 As discussed below, the role of expertise as a factor enabling the diffusion of Sino-EUropean governmental power among the Chinese population is crucial. However, this does not mean that our article is a critique of advanced liberalism. What we will be demonstrating in the following sections is that the way that Chinese sovereign power associates with Sino-EUropean governmental power bears certain similarities yet is not identical to governance features in advanced liberal democracies, in particular with regard to the resultant political subjectivisation.

To explain, compared with liberal and neoliberal understandings of governmentality and their emphasis on the interplay between governmental power and freedom,Footnote 35 the governance framework of EU-China relations appears to comply with a post-liberal form of governmentality wherein liberal features of governance are bypassed. Although the existence of these features is not negated, they are considered secondary to the actual ruling of populations.Footnote 36 Consequently, liberal values and norms, in particular the primordial emphasis on freedom, lose their centrality in governance. As in neoliberal governmentality, the burden of governance is transferred to citizens who are encouraged to regulate their own behaviour in a ‘do-it-yourself’ way, yet without this translating into liberal political subjectivities able to challenge the existing power nexus.Footnote 37 This post-liberal rationality of governance asks citizens to enable themselves under the condition of not being enabled too much. The objective of post-liberal rationality is the social construction of efficient political subjects, not of liberated political subjects. This insight is further illustrated in the article's penultimate section.

It may be counter-argued at this point that governmental power is exercised on behalf of territorially bound political subjects over an equally spatially bound population. This counterview implies that a joint exercise of governmental power by two distinct centres of authority and rule such as Brussels and Beijing is not feasible. Such a point confuses the judicial understanding of government (and the related executive authority in the context of a specific nation-state) with governance. Wittendorp stresses that ‘governmentality understands the international/global without premising such analyses on the alleged supremacy of the state. At the same time, this makes it possible to acknowledge that subjects are governed by forms of rule transgressing the territorial borders of the state.’Footnote 38 It is this ability of governmental power to expand beyond a nation-state's territory that allows for scholarly investigations of global and international versions of governmentality. Already in the early 2000s, Merlingen called for a governmentality framework for the investigation of intergovernmental organisations.Footnote 39 Larner and Walters continued with an edited volume on global governmentality,Footnote 40 and Sending and Neumann use the concept to flesh out the roles and political subjectivities of civil society organisations in international population policy.Footnote 41 Focusing on international cooperation, Jaeger approaches the reform of the United Nations as a modality of ‘managing and regulating the global population through a variety of governmental rationalities and techniques’.Footnote 42 On a similar note, Albert and Vasilache explore international cooperation in the Arctic, particularly how the Arctic is constructed as a governmentalised space of international regulation and management.Footnote 43 In addition, governmentality has been explored in EU studies ranging from investigations of how EU institutions socially construct governable spaces and manage the life of populations inside and outside the EUFootnote 44 to interpretations of specific EU policies through the governmentality lensFootnote 45 and recent explorations of the EU's cooperation with international organisations.Footnote 46 We engage with some of these post-Foucauldian voices as we problematise questions of institutionalisation and policy implementation in EU-China relations in the next section.

A post-liberal form of Sino-EUropean governmental power over the Chinese population

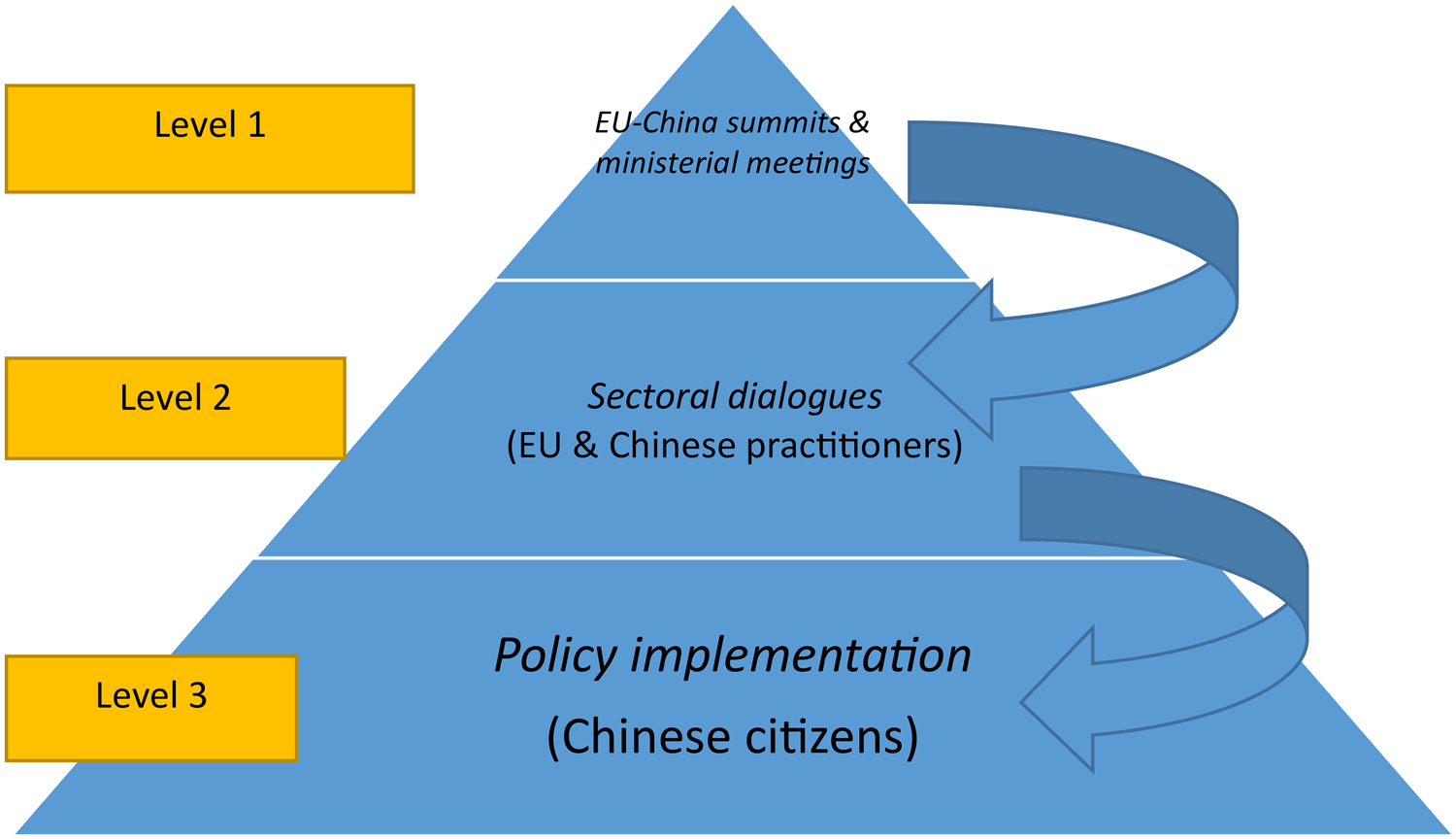

In what follows, we narrow down our empirical analysis to the post-2013 period. This is because in 2013 the EU and China agreed on the 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation (henceforth called the Strategic Agenda).Footnote 47 Since this important moment in the institutionalisation of Sino-EUropean cooperation, Sino-EUropean governmental power has been constructed in a sequence of steps. The first step is the institutionalisation of cooperation (Levels 1 and 2 in Figure 1), and the second step is policy implementation (Level 3 in Figure 1). As a political process or outcome, institutionalisation signals the regulatory capacity of governmental power. Governance practices such as EU-China summits, high-level dialogues, ministerial meetings, and sectoral dialogues are the political processes and products of the increasing institutionalisation of the collaboration between Brussels and Beijing. In the case of policy implementation, governance practices refer to the specific actions, mechanisms, initiatives, programmes, and projects that are developed and implemented as part of Sino-EUropean cooperation.

Figure 1. Institutional structure of EU-China cooperation and the flow of governmental power.

The hierarchical pyramid in Figure 1 depicts how governmental power flows (arrows in the scheme) from the higher echelons of Sino-EUropean leadership to Chinese citizens. Levels 1 and 2 consist of the governance practices that frame the institutionalisation of cooperation. Level 3 corresponds to the materialised policy outcomes (that is, policy implementation), also conceptualised here as governance practices. According to a post-liberal rationality, technologies of knowledge related to expertise facilitate technologies of power concerned with regulation and management. Whether governmental power flows from Levels 1 to 2 or from Levels 2 to 3, on the one hand a political mentality of linking expertise with efficient management of the population becomes evident and on the other, a tendency to construct self-serving and yet obedient political subjects among the Chinese population is observable. While in Lawrence's account of governmentality in EU governance we have a market rationality coexisting with a rights rationality, in the post-liberal governmentalised Sino-EUropean cooperation we see an effectiveness rationality resulting from apolitical, technologised expertise standing beyond existing liberal concerns.Footnote 48

Governance practices: Institutionalisation

The institutionalisation of Sino-EUropean cooperation is elaborate and multileveled. The EU-China annual summit provides strategic guidance from the top level of political leadership. This is followed by high-level dialogues, such as the annual strategic and economic and trade dialogues and the bi-annual people-to-people dialogues. At a lower level, there are regular meetings of counterparts and a range of sectoral dialogues covering almost every policy area and field of governance.Footnote 49 The extent of Sino-EUropean cooperation has gradually increased since the agreement of the Strategic Agenda in 2013. However, this does not necessarily entail the partnership's post-liberal governmentalisation, which would presuppose an expansion of the content of governance practices that regulate and manage different aspects of citizens’ lives, and do so by bypassing liberal concerns on good governance, the rule of law, and human rights.

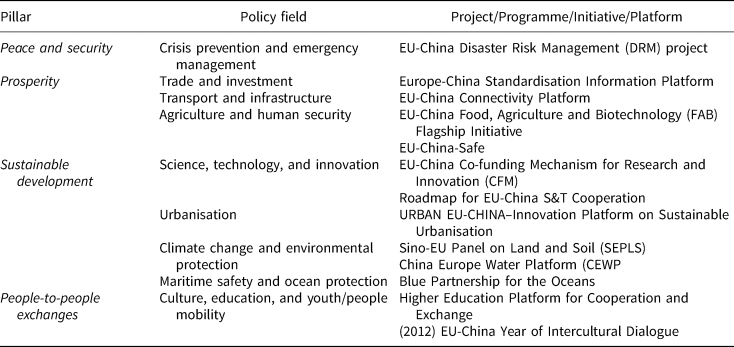

To prove this assumption, we start by examining the Strategic Agenda. The document includes broad areas of interest, also known as ‘pillars’, such as ‘peace and security’, ‘prosperity’, ‘sustainable development’, and ‘people-to-people exchanges’. The pillars are divided into domains.Footnote 50 The complex thematic diversification is further confirmed by the administrative allocation of sectoral dialogues for the majority of the specialised topics in the Strategic Agenda. For example, the trade policy sectoral dialogue focuses on international trade governance and how this is envisaged by the two sides, whereas the agricultural dialogue focuses on collaboration in agricultural production and goods.Footnote 51 The specificity of the areas of cooperation is arguably higher than that in any other EU partnership.Footnote 52

Due to its comprehensiveness, the Strategic Agenda has the potential to regulate every aspect of citizens’ lives by indirectly managing how they produce and work (for example, agriculture, industry), learn (science, technology, innovation, education, and youth), consume (energy, transportation) and socially behave (environmental protection, social progress). This division into different policy areas indicates how governmental power breaks down the sociopolitical realm of governance into smaller thematic categories so as to more easily and efficiently manage them. Concurring with Jaeger, governmentality entails a notion of ‘reprogramming’ life by categorising, distributing, and managing.Footnote 53

It becomes evident that this elaborate institutionalisation depends on a series of hierarchised, networked, and often overlapping policy fora and dialogues whose raison d’être is primarily efficiency, effectiveness, and business continuity in the governance of the partnership. Barry and Walters envisage the EU as ‘a network underpinned by the development of new information and communication technologies’.Footnote 54 Similarly, EU-China relations can be considered a form of interregional networked governance underpinned by technologies of expertise that interlink with the effective management of the Chinese population. In fact, jargon such as ‘efficiency’ and ‘effective(ness)’ is mechanistically repeated in the text of the Strategic Agenda (for example, ‘effective, coordinated and coherent responses to pressing global challenges’, ‘effective rules in key fields’, ‘resource efficiency agenda’, ‘more efficient, transparent, just and equitable system of global governance’). This automaticity reveals the extent to which a managerial rationale that prioritises effectiveness and efficiency has become normalised within the framework of the partnership. This does not mean that questions related to a liberal agenda of governance are not iterated in the Strategic Agenda. They are included in the document but deprioritised by the text itself. For instance, the question of human rights – a contentious issue that has traditionally hindered cooperation between liberally oriented Brussels and authoritarian Beijing – is mentioned only once in the 16 pages of the Strategic Agenda:

Deepen exchanges on human rights at the bilateral and international level on the basis of equality and mutual respect. Strengthen the Human Rights Dialogue with constructive discussions on jointly agreed key priority areas.Footnote 55

Such generic and declaratory wording allows both Brussels and Beijing to consent to cooperation. It does not specifically address human rights protection within China and it does not consider the question of human rights as a prerequisite for closer collaboration in other policy areas. The deprioritisation of human rights is even highlighted in the document's own structure and format, where the issue is mentioned as ‘key initiative’ number 8 under the ‘peace and security’ pillar.

The example of Sino-EUropean cooperation on climate change

The treatment of climate change within EU-China relations illustrates how the institutionalisation of Sino-EUropean cooperation complies with a post-liberal version of governmentality. First, the Strategic Agenda sets the foundations for collaboration on climate change by committing both sides to the UN operations on the matter (for example, works of UN Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC]), jointly supporting the further reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and cooperating ‘on achieving a strategic policy framework of green and low-carbon development for actively addressing global climate change’.Footnote 56 In this statement, we see a focus on achieving deliverables rather than on differences in liberal principles that may create obstacles to collaboration. These principles seem to be bracketed and set aside as not befitting what both the EU and China consider to be a primarily technical question. In other words, the political rationality that underpins Sino-EUropean cooperation on climate change and environmental governance conceptualises environmental challenges as technocratic issues that can be addressed outside the sphere of contestation resulting from politicised, norm- and value-driven divergence between Brussels and Beijing. Such insights resonate with Lawrence's argument that the EU's export of environmental norms complies with a market's rationality as in neoliberal governmentality.Footnote 57 As highlighted in the previous section, a post-liberal form of governmentality does not negate the neoliberal features of governmental power; on the contrary, these features are the building blocks on which a post-liberal mentality of governance is founded.

The rationality that demarcates Sino-EUropean cooperation in the context of environmental governance as highly technical and scientific, rather than political, is reproduced in the gradational policy design. The 2015 EU-China Summit addressed climate change by issuing an exclusive joint statement in which the two partners ‘commit to work together to reach an ambitious and legally binding agreement at the Paris Climate Conference in 2015’,Footnote 58 and to extend their collaboration on climate change to other international fora such as the G20, International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and International Maritime Organization (IMO).Footnote 59 The statement includes a series of detailed joint actions on, for example, ‘low carbon and climate resilient investments’ and ‘hydrofluorocarbons’ and mentions new concrete actions (for example, ‘carbon capture, utilization and storage in the framework of the Near Zero Carbon Initiative’).Footnote 60 The joint discourse on climate change thus becomes more specialised and scientific. It seems that political differences driven by the EU's liberal concerns are further marginalised as inappropriate for such technical issues. The EU's pragmatism in setting aside its liberal complaints against China so as not to jeopardise their mutually beneficial collaboration echoes a managerial urge for effectiveness, efficiency, and policy deliverables, which is again compatible with post-liberal governmentality. Hence, climate change remains on the agenda of the 18th EU-China Summit in 2016, with an emphasis on policy evaluation and the assessment of agreed joint actions:

In the area of the climate, the summit should advance the implementation of the Paris Agreement on climate change and assess the implementation of the EU-China Climate Change Declaration of 2015.Footnote 61

The constant institutional refinement of Sino-EUropean collaboration on climate change represents an expansion of governmental power, covering increasingly specific topics within the broader policy area. The intense governmentalisation of cooperation is tangibly demonstrated in the adoption of the Memorandum of Understanding to Enhance Cooperation on Emissions Trading and the Memorandum of Understanding on Circular Economy Cooperation, which concluded during the 20th EU-China Summit in 2018.Footnote 62 As in the previous documents, these memoranda are highly technical. They show the gradual normalisation of the ontological autonomy of seemingly technical issues from the bigger political picture of the partnership. Following a post-liberal rationality, Brussels and Beijing present joint environmental governance as feasible, capable of producing deliverables due to its technicality.

What further inferences can we draw from the example of cooperation on climate change? The institutionalisation of the partnership connotes the gradual social construction of a field of power that entangles EU and Chinese policymakers and practitioners in a single body of ‘governing ones’ who have unconsciously made use of institutional procedures, setting in motion practices of governance to manage the Chinese population. Institutionalisation has then been translated into technical policy actions that have a tangible impact on the lives of the ‘governed ones’, such as the EU-China Emission Trading Capacity Building project outlined in the memorandum mentioned above. Under the productive rationale of governmental power,Footnote 63 institutionalising Sino-EUropean cooperation has made it ontologically feasible to exercise governmental power over the Chinese population due to links with policy implementation (see Figure 1). In other words, policy actions, mechanisms, and projects flowing from the EU-China cooperation have become both contingent on and achievable through the institutional procedures set in place during the phase of institutionalisation. Agrawal reaches a similar conclusion using the epistemological lens of governmentality to explore environmental politics in India, highlighting that a ‘reorganization of institutional arrangements has facilitated changes in environmental practices and levels of involvement in government’.Footnote 64 What is more, these institutional arrangements have been stripped of political connotations and preconditions. The predominant rationale is that environmental governance is highly technical and dependent on scientific expertise. Therefore, it cannot be subject to politicisation.

It can be argued that the flow of power from the governing leaders and practitioners to the governed Chinese population is not politically intentional. Simply put, do EU and Chinese practitioners deliberately seek to regulate Chinese citizens’ lives when they further Sino-EUropean cooperation? It is true that the Foucauldian approach to governmentality does not extensively elaborate on questions of political agency.Footnote 65 Nevertheless, as the ontology of governmental power is founded on structural mechanisms, which are embedded and dependent on their spatio-temporal contexts, governmentality is related to structural explanations of power that admittedly downgrade the importance of political agency in governance. If this is so, one may question whether Sino-EUropean cooperation signifies any form of intentional power exercise at all. It is important to recognise that governmental power is never explained as the conscious decisions of practitioners seeking to exhaustively control the lives of the governed. The application of governmental power is indirect and subtle, so as not to provoke an immediate reaction from the governed population. This is achieved by capitalising on post-liberal thinking that presents as normal that governance in general is supposed to be a technical matter, an insight also shared by the governmentality-inspired study of advanced liberalism.Footnote 66 Therefore, any political doubts, whether they come from the governing or the governed ones, appear not to be particularly salient. The normalisation of Sino-EUropean governmental power through policy institutionalisation remains imperceptible. Nonetheless, even if citizens do not notice them, it does not mean that technologies of power and knowledge are not present. To render their operation more explicit, we now turn to policy implementation.

Governance practices: Projects, actions, and programmes

This subsection looks at Level 3 of the pyramid in Figure 1 and investigates the flow of governmental power from EU and Chinese politicians and policymakers to Chinese citizens. By looking at concrete activities, we problematise how governmental power reaches the Chinese population. As in our discussion of institutionalisation, we argue that policy implementation is consistent with a post-liberal rationality.

Concrete projects and activities are implemented to meet the key initiatives of the Strategic Agenda's four pillars.Footnote 67 Although some of the projects began before 2013, they were streamlined and incorporated into the overall institutional framework after 2013. Some examples of these concrete actions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of concrete actions of policy implementation within the EU-China Cooperation.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on information provided by the European Direct Contact Centre.

As shown by the thematic variety of the projects and initiatives summarised in Table 1, policy implementation affects many sociopolitical aspects of citizens’ lives. The activities in Table 1 imply that governmental power flows centrifugally: both vertically from higher to lower levels of political and administrative hierarchies, and horizontally across a wide range of issues. Using climate change again as an example, the Sino-EU Panel on Land and Soil (SEPLS) is a detailed project designed to put into action the levels of high institutionalisation already achieved on Sino-EUropean environmental governance. As a scientific body providing the EU Commission and the Chinese government with advice and expertise, the SEPLS draws together academic researchers, institutes, and think tanks from both Europe and China. It runs seminars on targeted topics of interest, organises working groups on policy elaboration, and publishes policy support documents and research projects to bridge the knowledge gap between the two sides. The SEPLS arguably prepares the administrative field of environmental governance for the further imposition of Sino-EUropean governmental power, creating the necessary technocratic and scientific preconditions for its continuous application. In addition, technicality, scientificity and expertise become drivers of the project's success, sidelining any political differences between the EU and China on how to tackle environmental protection. The project thus acquires an apolitical administrative identity that centres on efficiency and effectiveness rather than on the highly political questions of legitimation and authority. The EU channels funds to Beijing via these projects, even though it simultaneously criticises the regime's authoritarian practices. This contradictory behaviour is possible because the EU's insistence on liberal values and norms gets presented as a topic that is not suitable for and applicable in the case of technical projects. The ‘project-ness’ of EU governance ensures business continuity and hence effectiveness.Footnote 68 Under post-liberal governmentality, the EU's liberal criticism is retained but appears to function in a detached manner, as a high-level debate between the politicians of China, the EU and its member states, which may leave intact policy implementation, nonetheless.

The post-liberal regulatory capacity of governmental power is reflected in other projects, such as the Europe-China Standardization Information Platform, which has identified ten industrial sectors for standardisation between the two partners. Due to its complex technicality, the role of the EU in the Platform has remained vague even to Chinese decision-makers and practitioners. The numerous activities of the Platform have been dispersed among sectoral ministries and departments, agencies, research institutes, universities, and think tanks in China, which have carried out these activities with varying degrees of formality. Apart from three Annual Reviews, no clear description has been offered to Chinese practitioners about the objectives of the Platform.Footnote 69 This vagueness, paired with the informality of the implementation procedures, echoes research on how the exercise of governmental power over the population can be facilitated if its processes and objectives are generic, abstract, and informal.Footnote 70

This ambiguity chimes with a post-liberal rationale. A network of technocrats, experts and administrators from both the EU and China ‘scatter’ governmental power over the Chinese population in such an abstract way that is difficult to trace power back to its initial holders. From the perspective of the (Chinese) citizen, governmental power is not exercised by specific political agents, but structurally by the system of governance itself, which aims to secure the citizenry. Interestingly, as questions of political agency fade away, the liberal concern for accountability also dissipates. As Chandler states, ‘the discourse of governance focuses on technical and administrative capacity … rather than the representative legitimacy of policy making or its derivational authority’.Footnote 71 This means that ‘who’ questions – Who funds the project? Who claims ownership of the project? Who would be held responsible if the project fails? – are eventually presented to the citizens as matters of little importance.

The EU-China Disaster Risk Management project

A detailed analysis of all the projects and initiatives in Table 1 is not feasible due to the lack of available data and limitations of space.Footnote 72 This article will instead proceed with a discussion of the EU-China Disaster Risk Management (DRM) project to show how Sino-EUropean governmental power is reified through policy implementation. The DRM project has been of a small scale, given the size of China. However, it exhibits all of the traits of post-liberal governmentality.

The DRM project supports the 13th priority of the Strategic Agenda's ‘peace and security’ pillar, which calls for intensifying EU-China co-operation ‘based on the needs of people affected by disaster or crisis’.Footnote 73 The project illustrates the centrifugal nature of governmental power, which begins as an agreement struck by top-level governing actors and spreads downward and outward. Unlike other projects that affect the domestic orders of both partners, the DRM project explicitly supported the government of China by strengthening its nationwide disaster management system. It was designed to reduce the vulnerability of the Chinese people, and the adverse impact on them from natural and man-made disasters.Footnote 74 The project had three components – capacity development, institutional strengthening, and policy development and dialogueFootnote 75 – and fully complied with the EU's official discourse on building resilient societies, a discourse that has often been viewed through a governmentality lens.Footnote 76

The emphasis on managing risks within Chinese society indicates that this imposition of governmental power is meant to ensure the safety and survival of ordinary citizens. In response to the rise in manmade disasters in China, including epidemics, food safety issues, and environmental contamination, the Chinese government has undertaken measures to enhance its nationwide system of disaster risk management.Footnote 77 In this context, Beijing has adopted the EU's most up-to-date and best practices, particularly for issues related to prevention and preparedness and the key issue of multi-actor coordination throughout the disaster risk management cycle.Footnote 78 Disaster risk management thus signals subnational and transnational ramifications for the operation of governmental power.

Institutionally, the DRM project was part of a financing agreement between the EU and the government of China. It was implemented on the EU side through a grant contract between the EU Commission and the French Ministry of Interior, the latter leading a consortium of different institutional actors that includes governmental departments and agencies, research institutes, and universities across EU member states. Since 2012, the EU consortium has been working jointly with the Chinese government through China's National Institute for Emergency Management (NIEM) and the Emergency Management Office (EMO) to raise the latter's institutional capacity and establish an EU-China platform on disaster risk management. The objective has been to facilitate cooperation and coordination among actors at the national and international levels.Footnote 79 The joint bureaucratic and technocratic structures and institutions participating in the delivery of the project demonstrate how Sino-EUropean governmental power is diffused among the population through interconnected networks.

The DRM project supported the local governments of 15 different provinces in terms of institutional strengthening. For example, in Chengdu, Sichuan province, the project focused on strengthening community participation in crisis management and enhancing district and provincial capabilities. Significant progress has been made on the promotion of a network of volunteers and the development of regulations for their activities.Footnote 80 Furthermore, the project has engaged Chinese officials and senior staff from the EMO and practitioners involved in policy, strategy, and coordination at both the central and provincial levels. It has brought in experts and academic staff from the NIEM, government officials from ministries and government administrations, managers of relevant professional bodies, representatives of communities and non-state actors (for example, the Chinese Red Cross). These are not simply political, administrative, and societal actors but also policy stakeholders with a vested interest in disaster risk management who must effectively self-regulate their behaviour for the sake of the Chinese population's security and resilience.Footnote 81

The project's ultimate purpose has been to benefit the Chinese population, particularly communities living in disaster-prone areas, in the hope that Chinese citizens will learn how to take appropriate and timely action to protect themselves and their assets, which echoes Gordon's post-Foucauldian idea that governmental rationality both ‘totalises’ the population and ‘individualises’ political subjects within it.Footnote 82 Chinese citizens are expected to learn how to protect themselves in crises, consistent with the productive and enabling rationale endemic in governmental power. Sino-EUropean governmental power ‘travels’ through the Chinese administration and bureaucracy until it reaches the level of Chinese citizens. For instance, simulations of real-life scenarios were implemented within the context of the project. One of its most high-profile activities was a full-scale simulation at the Shanghai Chemical Park in May 2016, which involved more than three hundred participants.Footnote 83

Turning to technologies of knowledge, the project shows how governmental power is interdependent with regimes of expertise. The project's annual International Conference on Emergency Management has fostered the sharing of methods for enhancing collective knowledge of disasters, insights into the long-term effects of old and new risks and the development of risk awareness and adequate response strategies. The Chinese European Institute for Emergency Management (CEIEM) – which was heavily involved in the implementation of the DRM project – has been transformed into a platform for continued and regular policy dialogue and exchange of expertise between the EU and China. Consistent with Beijing's increasing interest in disaster risk reduction and emergency management, the DRM project has even supported the development of Master's programmes for Chinese officials and administrators, with over two hundred students having already completed their Master of Public Administration (MPA) at the Chinese Academy of Governance/Party School of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In addition, a number of short-term training programmes on crisis management and study trips to the EU have taken place.Footnote 84

The above discussion shows that the DRM project showcases the expansive ontology of governmental power. Its emphasis on vocational training in crisis management reminds us of the essential role of expertise in different versions of governmentality. Furthermore, the specialised knowledge and expertise engendered by the project will in turn support the continuous application of Sino-EUropean governmental power within Chinese society. The subtlety of governmental power is manifest in the way the project has infiltrated the Chinese domestic administrative order, with the exercise of power being transferred from the central government to provincial governments. It might be said that there has been no clear evidence of power being imposed in this transfer. However, as long as the DRM project has advised on best practices, lessons learnt, and alternatives, it has regulated and managed different aspects of crisis management that eventually touched the lives of Chinese citizens. It has done so under both the political control of the Chinese government and in compliance with EU expertise on crisis management, promoted and borne by the EU consortium. The joint power exercised over the Chinese population is thus the result of Chinese political control – the facet of power – and EU expertise – the facet of knowledge. This combination appears to occur outside the political dimension of Sino-European cooperation. As the administrative and scientific actors on both sides have framed these projects as managerial challenges that can be measured by means of milestones and deliverables, differences in broader political opinions and views have been set aside.

The question of political subjectivity

What sort of political subjectivities are associated with and emanate from the post-liberal governmentalisation of EU-China relations? In our analysis, we distinguish three forms of political subjectivity. The first is related to the EU, the second to the governing part of the Chinese population, and the third to the governed part of the Chinese population.

As China's partner, the EU projects a political subjectivity that is in accordance with its liberal ontology, its essential beliefs in multilateralism and its neoliberal devotion to policy effectiveness. In accordance with the official direction of EU foreign policy encapsulated in the ‘2016 EU Global Strategy’, EU institutions and member states are willing to engage with countries around the world, particularly major players such as China. Our study shows that EU-China relations are fundamentally motivated by policy effectiveness, with the EU undertaking a political role associated with the image of a reliable and knowledgeable collaborator that can ‘teach’ the Chinese authorities how to be more effective in different aspects of governance. At the same time, the fact that the EU keeps human rights, the rule of law and good governance on the agenda allows it to stay true, at least nominally, to its liberal values.Footnote 85 The governance practices in EU-China relations point to a post-liberal balance between neoliberal policy effectiveness and liberalism, which allows the EU to maintain both its liberal political subjectivity and its governance efficiency.

When examining the political subjectivity of the governing part of the Chinese population, Foucault's conviction that governmental power complements the application of sovereign and disciplinary powers resurfaces. Joint projects and political initiatives – such as those on climate change and disaster risk management discussed here – underpin the sovereign power of the Chinese state by increasing the latter's effectiveness. The fact that Chinese sovereign power is indirectly supported by EU expertise bestows upon the Chinese state a kind of legitimation that has nothing to do with the liberal, democratic ontology of representative governance; it instead flows from effectively managing the Chinese population and securing its safety, an insight that we fully grasp when further reflecting on the value-added characteristics of the DRM project. Ergo, Chinese statesmen and stateswomen are presented as politically capable and responsible leaders who are determined to protect China's population against all odds and actually deliver security and safety to the citizens.

However, the clearest expression of post-liberal governmentality is seen in the political subjectivities that are socially constructed for Chinese citizens. The application of Sino-EUropean governmental power results in empowered yet not emancipated political subjects. Beyond traditional definitions of emancipation offered by Frankfurt School's critical theory, we understand emancipated political subjects as political actors who can freely contest the practices of governance they are subjected to. The technologies of post-liberal governmentality that exist in EU-China relations do not establish the liberal plane of freedom that would allow Chinese citizens to question and challenge Sino-EUropean governmental power. Technologies of agency are indeed in place,Footnote 86 according to which citizens become capable of effectively managing their sociopolitical behaviour, supporting the role of the sovereign authorities and contributing to the effectiveness of governance practices, as tangibly demonstrated in the example of the DRM project. Yet, this facilitation of governance does not provide citizens with the potential to hinder the decisions of authorities; in fact, the citizens get disciplined in new practices for the sake of effective governance. Thus, governmentality entails technologies that render citizens ‘active’ and ‘experts of themselves’,Footnote 87 yet its post-liberal version dictates them to do so without granting them the potential to raise radical demands to overturn the unilateral imposition of governmental power from the rulers to the ruled.

Conclusion

As with all sociopolitical relations, Sino-EUropean cooperation has not been impenetrable to power. Practices of governance, whether in the form of institutionalisation or policy implementation, allow governmental power, which is jointly buttressed by Brussels and Beijing, to be imposed on Chinese citizens. Supported by a productive rationale, this joint form of power manages and regulates various aspects of Chinese citizens’ lives from urban safety to production, consumption, and social behaviour. Governmental power, however, is not crudely applied over the Chinese citizenry, compelling them to lead their lives in specific ways. The exercise of power described in this article is subtle and indirect, based on interlinked networks between the different institutions, norms, structures, and actors involved in governing the EU-China collaboration. Importantly, Sino-EUropean governmental power appears to comply with a post-liberal rationale that marginalises any liberal-oriented political differences between the two sides for the sake of effective and efficient governance. The post-liberal governmentalisation of EU-China relations has resulted in diversified political subjectivities for the EU, Chinese rulers, and Chinese citizens. The EU has managed to promote its liberal image, while Chinese rulers have projected an image of capable, resolute, and effective leadership. At the same time, Sino-EUropean governmental power has contributed to the social construction of Chinese political subjects who are capable of assisting in governance practices, yet without questioning the absolute authority of the Chinese state.

Some reflection on the broader political implications of the post-liberal governmentalisation of EU-China relations seems necessary. Sino-EUropean cooperation can be seen as a medium of European governance and, more precisely, as a tool for the EU to apply its governmental power internationally, with an indirect effect on the lives of citizens who are far from any EU country. The nexus of power relations that the EU has gradually developed in different parts of the world demonstrates a projection of governmental power based on the policy networks of EU governance. If this is a valid point, EU scholarship may as well ignore the long-winded, rigid, and often sterile debate on EU actornessFootnote 88 and focus instead on how the EU uses its reserves of governmental power and whom in the world this power reaches. Although in this analysis we focus exclusively on EU-China relations and do not aim to generalise, our insights raise questions about the extent to which governmentality, particularly in its post-liberal form, can help us reread the governance practices of EU foreign policy, for instance the EU's partnership with the Russian Federation.

Moreover, we should note further implications of Sino-EUropean governmental power for the Chinese party state in terms of post-liberal governmentality. The People's Republic of China is governed according to a one-party system. The Chinese Communist Party is the sole legitimate representative of the country's regime (that is, socialism with Chinese characteristics). State and party structures are often equated, ensuring the political leaders a tight grip on Chinese society that depends on a mixture of disciplinary, sovereign, and governmental power. The combination of EU and Chinese practices, techniques, and rationalities of governance depicted in this article seems to further support the tight control and management of an already disciplined Chinese citizenry, a situation that is presented as a normalised sociopolitical phenomenon.

Such insights pave the way for normative reflections beyond the scope of this article. Cooperation between Brussels and Beijing has a performative dimension with normative implications. As the EU collaborates with China and indirectly participates in the country's governance through joint projects, initiatives, and platforms, it validates the domestic choices made by Chinese statesmen and stateswomen. Future research may explore whether there is any room for Sino-EUropean governmental power to develop a more liberal aspect, which could enable Chinese citizens to develop liberal democratic subjectivities, or whether it will continue to operate under a post-liberal rationale, independent from the broader political differences between the EU and China.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers of the Review of International Studies, as well as Michael Merlingen for their helpful comments. They would also like to thank the Department of International Studies at Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) for supporting Open Access publication. A previous version of the article was presented at the 2019 EUSA International Biennial Conference in Denver, USA.