1. Introduction

Most massive galaxies host a central supermassive black hole (SMBH); however, the origin of these objects remains uncertain. The canonical summary of possible formation pathways was first laid out in the Halley Lecture of 1978 at Oxford University (Rees Reference Begelman and Rees1978). Within the so-called Rees diagram (see also Figure 1), supermassive stars (SMSs) (Hoyle & Fowler Reference Hoyle and Fowler1963; Iben Reference Iben1963), dense stellar clusters (e.g., Begelman & Rees Reference Begelman and Rees1978), and a host of other objects were laid out as possible intermediaries. Many of these hypothesised progenitor objects were initially suggested to actually be the sources powering the emission seen in active galactic nuclei, before mounting observational evidence made it clear that these were in fact accreting SMBHs (Rees Reference Rees1984). Common to all of the SMBH progenitor channels in Figure 1 is the concentration of a large quantity of gas in a sufficiently small volume, leading to runaway black hole growth. How often each channel may be realised in nature, however, remains an outstanding problem. The majority of these scenarios remain plausible but unproven today.

Figure 1. Original diagram from Rees (Reference Rees1978, Reference Rees1984), outlining the possible formation pathways for supermassive black holes. In this review, as in the conference, our focus is on the left side of the diagram.

By far the greatest challenge to any theory of SMBH formation has been the discovery of luminous (![]() $$ \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} {10^{13}}{{\rm{L}}_ \odot }$$) quasars at

$$ \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} {10^{13}}{{\rm{L}}_ \odot }$$) quasars at ![]() $z\sim7$, when the Universe was only

$z\sim7$, when the Universe was only ![]() ${\sim}800\,\mathrm{Myr}$ old (e.g., Mortlock et al. Reference Mortlock2011; Wu et al. Reference Wu2015; Bañados et al. Reference Bañados2018). The masses of these objects are all

${\sim}800\,\mathrm{Myr}$ old (e.g., Mortlock et al. Reference Mortlock2011; Wu et al. Reference Wu2015; Bañados et al. Reference Bañados2018). The masses of these objects are all ![]() $\mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$, inferred from the breadth of the observed Mg ii 2 798 Å line (e.g., McLure & Dunlop Reference McLure and Dunlop2004), and consistent with their luminosities being near the Eddington limit. Among the most troubling examples, SDSS J010013.02+280225.8 is a known redshift ~6.3 quasar that is already

$\mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$, inferred from the breadth of the observed Mg ii 2 798 Å line (e.g., McLure & Dunlop Reference McLure and Dunlop2004), and consistent with their luminosities being near the Eddington limit. Among the most troubling examples, SDSS J010013.02+280225.8 is a known redshift ~6.3 quasar that is already ![]() $1.2 \times\,10^{10}\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ (Wu et al. Reference Wu2015), while even earlier in the Universe, ULAS J134208.10+092838.61 is a

$1.2 \times\,10^{10}\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ (Wu et al. Reference Wu2015), while even earlier in the Universe, ULAS J134208.10+092838.61 is a ![]() $0.8\times10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ quasar at

$0.8\times10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ quasar at ![]() $z=7.54$. How did these black holes reach of order 1–10 billion solar masses in the first billion years of the Universe?

$z=7.54$. How did these black holes reach of order 1–10 billion solar masses in the first billion years of the Universe?

The problem is best illustrated if we consider the optimistic case of persistently Eddington-limited accretion for the entire prior lifetimes of these objects. A black hole may only grow in this way from an initial ‘seed’ mass ![]() $M_{0}$ to a given mass

$M_{0}$ to a given mass ![]() $M_{\rm{BH}}$ in a time:

$M_{\rm{BH}}$ in a time:

where ![]() $\epsilon\sim 0.1$ is the typical radiative efficiency for thin-disk accretion (see, e.g., Shakura & Sunyaev Reference Shakura and Sunyaev1973, for discussion). Even in this most favourable scenario, producing a

$\epsilon\sim 0.1$ is the typical radiative efficiency for thin-disk accretion (see, e.g., Shakura & Sunyaev Reference Shakura and Sunyaev1973, for discussion). Even in this most favourable scenario, producing a ![]() ${{\gt}}10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ quasar from a typical

${{\gt}}10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ quasar from a typical ![]() $$\sim10 - 100\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }$$ Pop III remnant would require an accretion time greater than the age of the Universe at

$$\sim10 - 100\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }$$ Pop III remnant would require an accretion time greater than the age of the Universe at ![]() $z\sim7$, unless significantly lower radiative efficiencies may be invoked (i.e., strongly ‘super-Eddington,’ accretion, see, e.g., Natarajan Reference Natarajan2014; Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi, Kashiyama, Visbal and Haiman2016, for further discussion). Even so, numerical simulations suggest that most of such stellar-mass Pop III black holes were likely to have been ‘born starving’, and unable to grow substantially via accretion early in the Universe, particularly due to their strong ionising feedback and possible ejection from their halos via dynamical 3-body interactions (e.g., Johnson & Bromm Reference Johnson and Bromm2007; Whalen Fryer Reference Whalen and Fryer2012; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Regan, Downes, Norman, O’Shea and Wise2018).

$z\sim7$, unless significantly lower radiative efficiencies may be invoked (i.e., strongly ‘super-Eddington,’ accretion, see, e.g., Natarajan Reference Natarajan2014; Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi, Kashiyama, Visbal and Haiman2016, for further discussion). Even so, numerical simulations suggest that most of such stellar-mass Pop III black holes were likely to have been ‘born starving’, and unable to grow substantially via accretion early in the Universe, particularly due to their strong ionising feedback and possible ejection from their halos via dynamical 3-body interactions (e.g., Johnson & Bromm Reference Johnson and Bromm2007; Whalen Fryer Reference Whalen and Fryer2012; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Regan, Downes, Norman, O’Shea and Wise2018).

These simple considerations provide a strong hint that very rapid accretion rates and a massive ‘seed’ are necessary ingredients in the origin of the most massive high-z quasars, although relatively lower-mass progenitors may yet be plausible for these objects (see, e.g., Natarajan & Volonteri Reference Natarajan and Volonteri2012; Pezzulli et al. Reference Pezzulli, Volonteri, Schneider and Valiante2017, and references therein), and can reproduce the observed M-σ relation in the local Universe (see, e.g., Taylor & Kobayashi Reference Taylor and Kobayashi2014, Reference Taylor and Kobayashi2015). The relative abundance of light and massive seeds, and their role in the origin of all SMBHs, depends sensitively on the prevalence of halos where the formation of massive black hole seeds is possible (e.g., Lodato & Natarajan Reference Lodato and Natarajan2007; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Khochfar, Johnson, Neistein, Dalla Vecchia and Livio2012; Dijkstra, Ferrara, & Mesinger Reference Dijkstra, Ferrara and Mesinger2014; Habouzit et al. Reference Habouzit, Volonteri, Latif, Dubois and Peirani2016a).

The first question then becomes what massive seed formation channels are viable. The collapse of dense stellar clusters to form a massive protostar has been considered for decades (e.g., Begelman & Rees Reference Begelman and Rees1978). The necessary inefficiency of this process, however, in which much of the original energy and angular momentum of the system are shed with stellar mass ejected in 3-body interactions, strongly limits its ability to produce extremely massive seeds (see, e.g., Latif, Schleicher, & Hartwig Reference Latif, Schleicher and Hartwig2016a, and references therein). More exotic channels, such as the growth of primordial black holes (Zel’dovich & Novikov Reference Zel’dovich and Novikov1967), or intermediate-mass black holes (IMBH) formed from dissipative dark matter (D’Amico et al. Reference D’Amico, Panci, Lupi, Bovino and Silk2018), remain somewhat speculative and require further study. A promising model for producing both large seed masses and rapid accretion rates has emerged in the atomically cooled halo scenario (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008), in which exposure to a strong Lyman–Werner flux from an adjacent Pop III halo destroys the molecular hydrogen in a primordial halo which has not yet undergone fragmentation (Regan et al. Reference Regan, Visbal, Wise, Haiman, Johansson and Bryan2017). This prevents ‘normal’ Pop III star formation and allows infall rates of up to ![]() $$\sim0.1 - 1.0\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }/{\rm{yr}}$$. Numerical simulations have consistently shown such high accretion rates leading to the formation of a nuclear-burning, SMS, which will later undergo collapse through a relativistic instability (referred to in the literature as a ‘direct collapse black hole’, DCBH), leaving a massive black hole remnant (Hosokawa et al. Reference Hosokawa, Yorke, Inayoshi, Omukai and Yoshida2013; Umeda et al. Reference Umeda, Hosokawa, Omukai and Yoshida2016; Woods et al. Reference Woods, Heger, Whalen, Haemmerlé and Klessen2017; Haemmerlé et al. Reference Haemmerlé, Woods, Klessen, Heger and Whalen2018a).

$$\sim0.1 - 1.0\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }/{\rm{yr}}$$. Numerical simulations have consistently shown such high accretion rates leading to the formation of a nuclear-burning, SMS, which will later undergo collapse through a relativistic instability (referred to in the literature as a ‘direct collapse black hole’, DCBH), leaving a massive black hole remnant (Hosokawa et al. Reference Hosokawa, Yorke, Inayoshi, Omukai and Yoshida2013; Umeda et al. Reference Umeda, Hosokawa, Omukai and Yoshida2016; Woods et al. Reference Woods, Heger, Whalen, Haemmerlé and Klessen2017; Haemmerlé et al. Reference Haemmerlé, Woods, Klessen, Heger and Whalen2018a).

High baryonic streaming velocities relative to dark matter within some regions in the early Universe may provide another means to suppress star formation in low mass halos (Tseliakhovich & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich and Hirata2010a) and promote the growth of a DCBH seed (Tanaka & Li Reference Tanaka and Li2014a; Hirano et al. Reference Hirano, Hosokawa, Yoshida and Kuiper2017), although such a mechanism may primarily act as a catalyst within the atomically cooled halo model (e.g., Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017). Other alternative channels for producing massive seeds, including massive high-z galaxy mergers (Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, Kazantzidis, Escala and Callegari2010; Mayer & Bonoli Reference Mayer and Bonoli2018) and the disruption of dense stellar clusters (e.g., Begelman & Rees Reference Begelman and Rees1978; Katz, Sijacki, & Haehnelt Reference Katz, Sijacki and Haehnelt2015; Sakurai et al. Reference Sakurai, Yoshida, Fujii and Hirano2017), have also been the subject of significant investigation, although questions remain regarding the nature of the remnants they produce (see, e.g., Latif & Ferrara Reference Latif and Ferrara2016, for a thorough discussion).

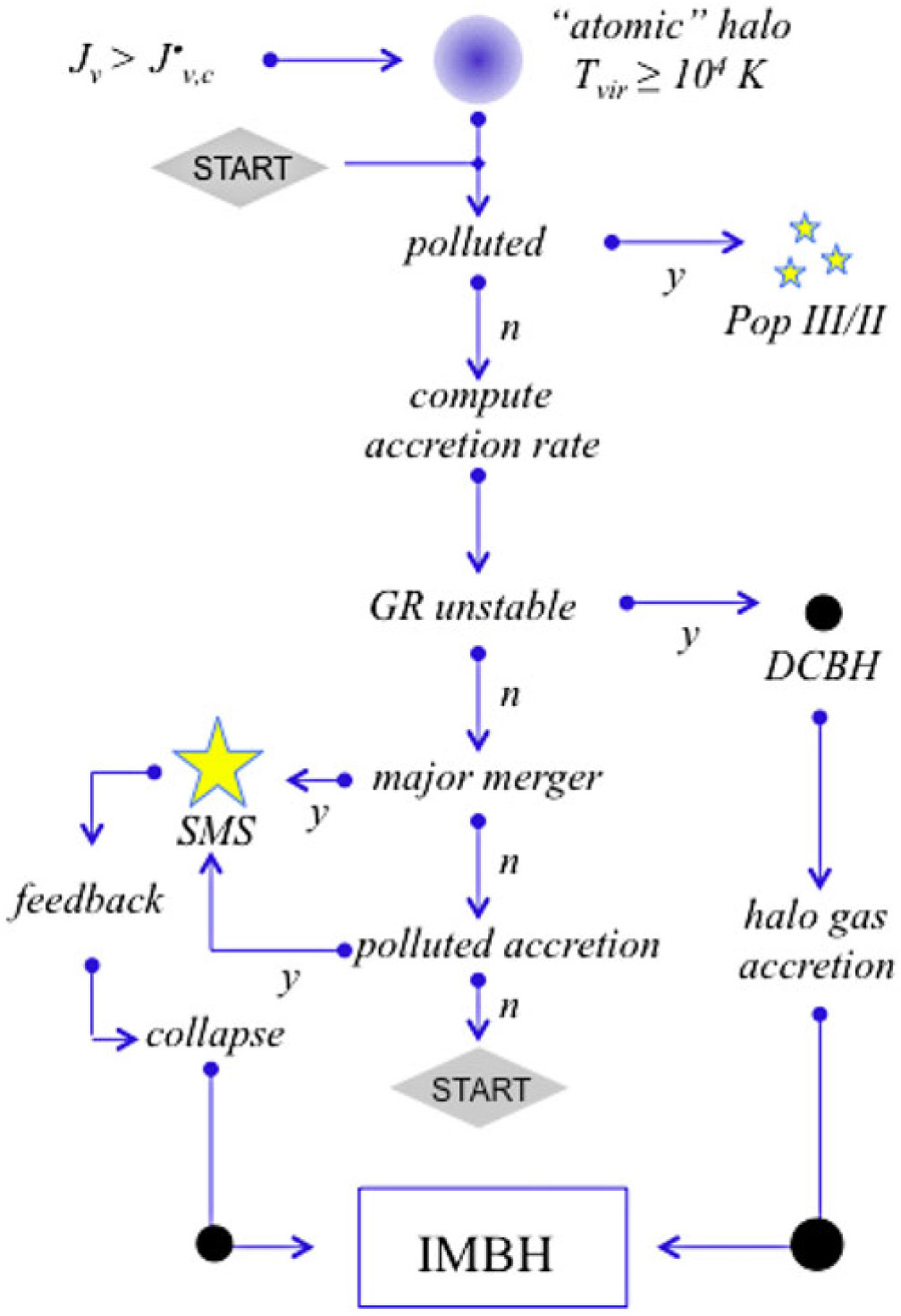

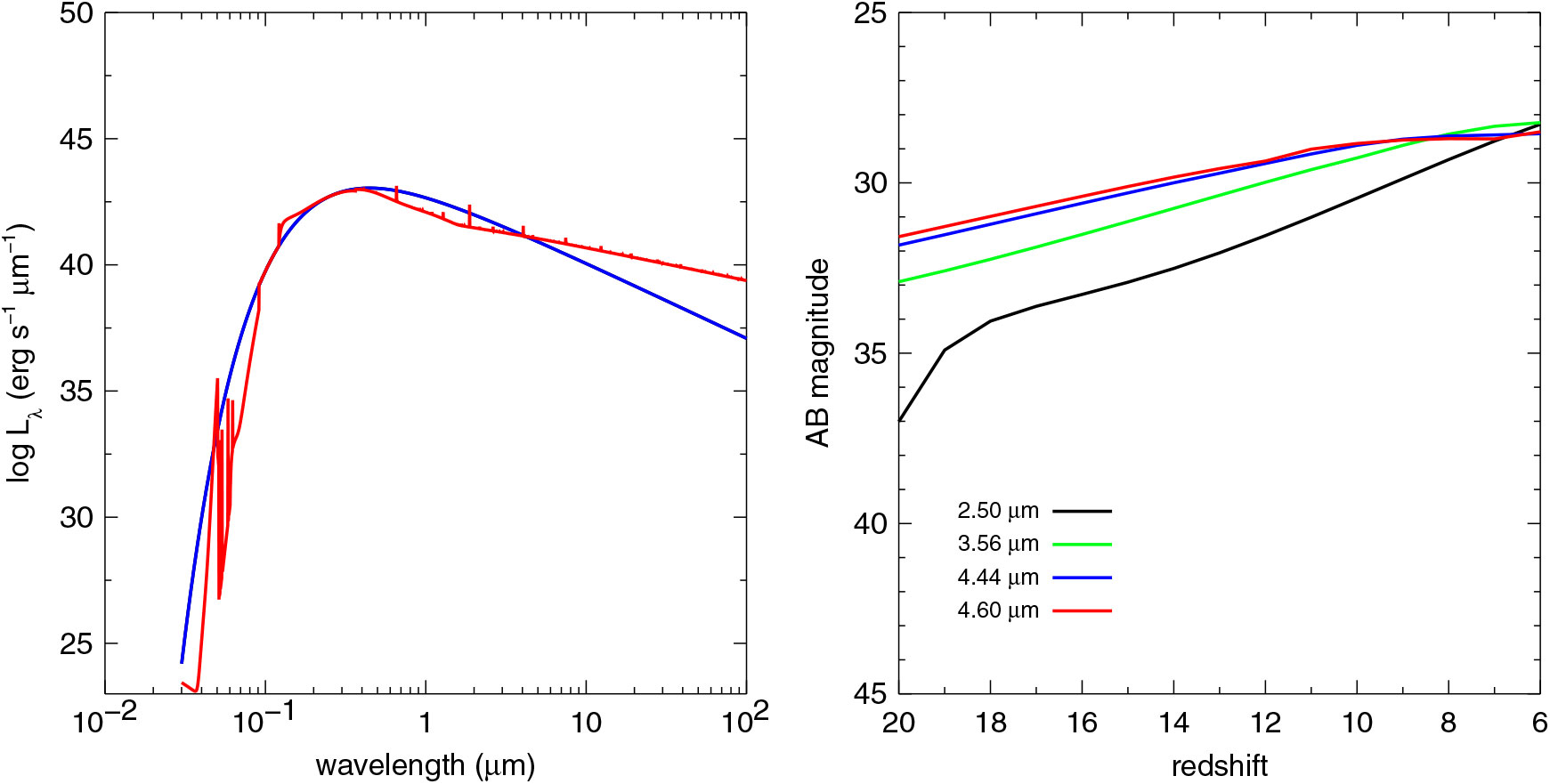

The upcoming launch of next-generation observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and Euclid, as well as ground-based extremely large telescopes (ELTs), promise to yield great insight into the nature and number of the most luminous objects in the early Universe. Already, observational case studies such as the Lyman-α emitter CR7 have provided invaluable tests for our ability to distinguish between models for luminous high-z objects (Sobral et al. Reference Sobral, Matthee, Darvish, Schaerer, Mobasher, Röttgering, Santos and Hemmati2015; Pallottini et al. Reference Pallottini2015; Hartwig et al. Reference Hartwig2016; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Johnson, Khochfar, Pellegrini, Rydberg, Klessen and Oesch2017b; Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, McLure, Dunlop, McLeod, Stanway, Eldridge and Jarvis2017b; Pacucci et al. Reference Pacucci, Pallottini, Ferrara and Gallerani2017a). The ongoing search for IMBHs in the nearby Universe may soon allow us to constrain the distribution of black hole seed masses (Mezcua Reference Mezcua2017). With this progress in mind, the workshop Titans of the Early Universe: The Origin of the First Supermassive Black Holes was held in late November of 2017 in Prato, Italy, with the goal of determining what theoretical and observational progress can now be made in understanding the plausibility, origin, and nature of SMSs and their direct collapse as massive black hole seeds, as well as the role of alternative formation channels. With respect to Figure 1, then, our focus is on the left side of the diagram, and in particular all paths which pass through a ‘SMS’ phase.

In the following, we begin in Section 2 by providing a summary of some of the latest theoretical developments in understanding how the extremely rapid accretion rates (![]() $$\sim0.1 - 1\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }/{\rm{yr}}$$) needed to fuel the growth of massive black hole seeds and very high-z quasars may be achieved, what effects may moderate or enhance this growth, and how progress can be made in future simulations. Then, in Section 3, we outline the recent numerical results which have reached a consensus on the initial product of these extreme accretion rates: high-entropy, hydrostatic nuclear-burning SMSs, which collapse through a relativistic instability to produce massive (

$$\sim0.1 - 1\,{{\rm{M}}_ \odot }/{\rm{yr}}$$) needed to fuel the growth of massive black hole seeds and very high-z quasars may be achieved, what effects may moderate or enhance this growth, and how progress can be made in future simulations. Then, in Section 3, we outline the recent numerical results which have reached a consensus on the initial product of these extreme accretion rates: high-entropy, hydrostatic nuclear-burning SMSs, which collapse through a relativistic instability to produce massive (![]() ${\sim}10^{5}\, \mathrm{M}_{\odot}$) black hole seeds. In Section 4, we discuss the relative formation rates of light and massive seeds, the influence of still-uncertain parameterised physics, and future prospects for encapsulating the underlying physics of massive seed/DCBH formation in simplified prescriptions for use in population modelling. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss observational prospects for detecting evidence of black hole seed formation channels (and, eventually, determining the initial black hole ‘seed mass function’) using next-generation observatories, before concluding in Section 6.

${\sim}10^{5}\, \mathrm{M}_{\odot}$) black hole seeds. In Section 4, we discuss the relative formation rates of light and massive seeds, the influence of still-uncertain parameterised physics, and future prospects for encapsulating the underlying physics of massive seed/DCBH formation in simplified prescriptions for use in population modelling. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss observational prospects for detecting evidence of black hole seed formation channels (and, eventually, determining the initial black hole ‘seed mass function’) using next-generation observatories, before concluding in Section 6.

2. How could SMSs form?

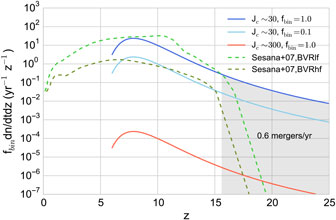

Independent of whether the seeds of the most massive high-z quasars are light or heavy, there is a growing consensus that sustained extremely high accretion rates are a vital ingredient in their origin. The central problem is that the growth of black holes via mergers alone is unlikely to produce ![]() ${\sim} 10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ black holes by

${\sim} 10^{9}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$ black holes by ![]() $z\sim7$ (e.g., Sesana et al. Reference Sesana, Volonteri and Haardt2007; Tanaka & Haiman Reference Tanaka and Haiman2009; Natarajan Reference Natarajan2011, see Section 4 for further discussion). Rapid accretion rates (

$z\sim7$ (e.g., Sesana et al. Reference Sesana, Volonteri and Haardt2007; Tanaka & Haiman Reference Tanaka and Haiman2009; Natarajan Reference Natarajan2011, see Section 4 for further discussion). Rapid accretion rates (![]() $$ \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over {\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 0.1{\mkern 1mu} {{\rm{M}}_ \odot }{\mkern 1mu} {\rm{y}}{{\rm{r}}^{ - 1}}$$) are also essential if any DCBH seeds are to pass through a supermassive (

$$ \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over {\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 0.1{\mkern 1mu} {{\rm{M}}_ \odot }{\mkern 1mu} {\rm{y}}{{\rm{r}}^{ - 1}}$$) are also essential if any DCBH seeds are to pass through a supermassive (![]() ${\sim} 10^{5}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$) stellar evolutionary phase, as the Eddington limit imposes a maximum nuclear burning lifetime of

${\sim} 10^{5}\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}$) stellar evolutionary phase, as the Eddington limit imposes a maximum nuclear burning lifetime of ![]() ${\sim}2\,\mathrm{Myr}$ for these objects.

${\sim}2\,\mathrm{Myr}$ for these objects.

Over the last two decades, numerical simulations of the collapse of primordial halos have grown increasingly sophisticated. Early numerical work focussed on investigating the collapse of low angular momentum halos (e.g., Loeb & Rasio Reference Loeb and Rasio1994; Begelman, Volonteri, & Rees Reference Begelman, Volonteri and Rees2006; Lodato & Natarajan Reference Lodato and Natarajan2006). It was soon understood that the dissociation of molecular hydrogen by Lyman–Werner radiation from the first stars could produce primordial halos in which collisionally excited atomic line transitions dominate cooling, allowing the isothermal collapse of such halos at ![]() ${\sim} 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ (Haiman, Rees, & Loeb Reference Haiman, Rees and Loeb1997). Since both the Jeans mass and the infall rate scale with the cube of the sound speed, and hence as

${\sim} 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ (Haiman, Rees, & Loeb Reference Haiman, Rees and Loeb1997). Since both the Jeans mass and the infall rate scale with the cube of the sound speed, and hence as ![]() $T^{3/2}$, where T is the temperature, such ‘atomically cooled halos’ provide a natural means for producing the conditions necessary for the formation of early quasars from massive seeds (e.g., Volonteri Reference Volonteri2010, and references therein). Initial efforts to simulate the collapse of atomically cooled halos presumed the prior destruction of

$T^{3/2}$, where T is the temperature, such ‘atomically cooled halos’ provide a natural means for producing the conditions necessary for the formation of early quasars from massive seeds (e.g., Volonteri Reference Volonteri2010, and references therein). Initial efforts to simulate the collapse of atomically cooled halos presumed the prior destruction of ![]() $\rm{H}_{2}$ (e.g., Bromm & Loeb Reference Bromm and Loeb2003; Wise, Turk, & Abel Reference Wise, Turk and Abel2008; Regan & Haehnelt Reference Regan and Haehnelt2009a, b). Subsequent work, however, has focussed on determining the initial conditions under which such a halo may arise, including the critical intensity for Lyman–Werner radiation, required to completely suppress

$\rm{H}_{2}$ (e.g., Bromm & Loeb Reference Bromm and Loeb2003; Wise, Turk, & Abel Reference Wise, Turk and Abel2008; Regan & Haehnelt Reference Regan and Haehnelt2009a, b). Subsequent work, however, has focussed on determining the initial conditions under which such a halo may arise, including the critical intensity for Lyman–Werner radiation, required to completely suppress ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling within a halo (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Shang, Bryan, & Haiman Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010). This quantity (‘

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling within a halo (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Shang, Bryan, & Haiman Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010). This quantity (‘![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$’) is conventionally parameterised in the literature in terms of the specific intensity at the Lyman limit,

$J_{\rm{crit}}$’) is conventionally parameterised in the literature in terms of the specific intensity at the Lyman limit, ![]() $J_{\rm LW}$, expressed in units of

$J_{\rm LW}$, expressed in units of ![]() $10^{-21}$ erg

$10^{-21}$ erg ![]() ${\rm{s}}^{-1}$ cm

${\rm{s}}^{-1}$ cm![]() $^{-2}$

$^{-2}$ ![]() ${\rm{Hz}}^{-1}$

${\rm{Hz}}^{-1}$ ![]() ${\rm{sr}}^{-1}$ (e.g., Omukai Reference Omukai2001). The overall picture which has emerged is that a strong Lyman–Werner flux, provided by a nearby halo which has recently undergone Pop III fragmentation, can indeed produce an atomically cooled halo (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Regan et al. Reference Regan, Visbal, Wise, Haiman, Johansson and Bryan2017). The number density of DCBHs which may be formed in this way is understood to vary as

${\rm{sr}}^{-1}$ (e.g., Omukai Reference Omukai2001). The overall picture which has emerged is that a strong Lyman–Werner flux, provided by a nearby halo which has recently undergone Pop III fragmentation, can indeed produce an atomically cooled halo (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Regan et al. Reference Regan, Visbal, Wise, Haiman, Johansson and Bryan2017). The number density of DCBHs which may be formed in this way is understood to vary as ![]() $J_{\rm LW}^{-4}$ (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Inayoshi & Tanaka Reference Inayoshi and Tanaka2015; Chon et al. Reference Chon, Hirano, Hosokawa and Yoshida2016). Varying estimates for

$J_{\rm LW}^{-4}$ (e.g., Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Haiman, Mesinger and Wyithe2008; Inayoshi & Tanaka Reference Inayoshi and Tanaka2015; Chon et al. Reference Chon, Hirano, Hosokawa and Yoshida2016). Varying estimates for ![]() $J_{\rm{ crit}}$ correspond to the ~8 orders of magnitude variation in existing estimates for the number density of DCBHs (see discussion in Section 4.2); whether a strong Lyman–Werner flux alone is primarily responsible for triggering DCBH formation is increasingly in doubt however, and remains an area of active study.

$J_{\rm{ crit}}$ correspond to the ~8 orders of magnitude variation in existing estimates for the number density of DCBHs (see discussion in Section 4.2); whether a strong Lyman–Werner flux alone is primarily responsible for triggering DCBH formation is increasingly in doubt however, and remains an area of active study.

This ‘synchronised pairs’ model (Visbal, Haiman, & Bryan Reference Visbal, Haiman and Bryan2014b) implies very strict constraints on the timing, evolution, and separation of any pair of primordial halos which may provide a site for the formation of a massive black hole seed (Visbal, Haiman, & Bryan Reference Visbal, Haiman and Bryan2014a; Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Ferrara and Mesinger2014; Regan et al. Reference Regan, Visbal, Wise, Haiman, Johansson and Bryan2017). Many questions remain, however, regarding the precise conditions under which atomically cooled halos could form and plausibly reproduce the masses and space density of high-z quasars (Latif & Ferrara Reference Latif and Ferrara2016). To what extent does fragmentation pose a problem for the formation of SMSs (e.g., Chon et al. Reference Chon, Hirano, Hosokawa and Yoshida2016; Regan & Downes Reference Regan and Downes2018a)? Can SMSs form without an atomically cooled halo, e.g., with lower-mass star formation suppressed via high baryonic streaming velocities relative to dark matter in the early Universe, or is this only complementary to the standard scenario (Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017)? These questions, as well as the next steps needed to make further progress in numerical simulations of atomically cooled halos, are discussed in the following section.

2.1.  ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ dissociation in primordial halos

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ dissociation in primordial halos

2.1.1. Important reactions

The birth of the first stars (Pop III) in the Universe also marked the onset of stellar radiative feedback. This must then be accounted for in any self-consistent treatment of subsequent star formation. In addition to hydrogen-ionising photons (with ![]() $E{\gt}13.6\,\mathrm{eV}$), stellar populations emit photons in two other energy bands which are of vital importance in determining the thermal and chemical state of primordial star-forming halos. Following Agarwal (Reference Agarwal2018), we describe each of these in turn, before returning to address the treatment of irradiating stellar spectra in assessing the conditions necessary for the formation of atomically cooled halos (and, perhaps, massive black hole seeds).

$E{\gt}13.6\,\mathrm{eV}$), stellar populations emit photons in two other energy bands which are of vital importance in determining the thermal and chemical state of primordial star-forming halos. Following Agarwal (Reference Agarwal2018), we describe each of these in turn, before returning to address the treatment of irradiating stellar spectra in assessing the conditions necessary for the formation of atomically cooled halos (and, perhaps, massive black hole seeds).

Photons in the Lyman–Werner band, with energies ![]() $$11.2\,{\rm{eV}} \lt E \lt 13.6\,{\rm{eV}}$$, can dissociate molecular hydrogen (

$$11.2\,{\rm{eV}} \lt E \lt 13.6\,{\rm{eV}}$$, can dissociate molecular hydrogen (![]() $\mathrm{H}_{2}$). They have insufficient energy, however, to ionise atomic hydrogen, allowing Lyman–Werner photons which escape from nascent halos to travel substantial path lengths in the early Universe, destroying

$\mathrm{H}_{2}$). They have insufficient energy, however, to ionise atomic hydrogen, allowing Lyman–Werner photons which escape from nascent halos to travel substantial path lengths in the early Universe, destroying ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ in other primordial minihalos and potentially delaying further Pop III star formation (Haiman, Rees, & Loeb Reference Haiman, Rees and Loeb1996; Ciardi, Ferrara, & Abel Reference Ciardi, Ferrara and Abel2000). Radiative de-excitations of excited

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ in other primordial minihalos and potentially delaying further Pop III star formation (Haiman, Rees, & Loeb Reference Haiman, Rees and Loeb1996; Ciardi, Ferrara, & Abel Reference Ciardi, Ferrara and Abel2000). Radiative de-excitations of excited ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ provide a powerful source of cooling in primordial halos. In its absence, the next available strong cooling term becomes radiative transitions of collisionally excited atomic hydrogen, requiring gas temperatures of

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ provide a powerful source of cooling in primordial halos. In its absence, the next available strong cooling term becomes radiative transitions of collisionally excited atomic hydrogen, requiring gas temperatures of ![]() ${\sim} 8\,000\,\mathrm{K}$. For the subsequent isothermal collapse, such high temperatures imply a Jeans mass of

${\sim} 8\,000\,\mathrm{K}$. For the subsequent isothermal collapse, such high temperatures imply a Jeans mass of ![]() ${\sim} 10^6\,\mathrm{M}_\odot$ at

${\sim} 10^6\,\mathrm{M}_\odot$ at ![]() $n\sim10^3\,{\rm cm}^{-3}$. Therefore, atomically cooled halos undergoing isothermal collapse permit the birth of truly supermassive objects, potentially leading to the formation of, e.g., DCBHs and/or quasi-stars (see subsequent sections).

$n\sim10^3\,{\rm cm}^{-3}$. Therefore, atomically cooled halos undergoing isothermal collapse permit the birth of truly supermassive objects, potentially leading to the formation of, e.g., DCBHs and/or quasi-stars (see subsequent sections).

Previous efforts to model the effect of a photo-dissociating background on star formation in the early Universe have focussed on the strength of this LW radiation (![]() $J_{\rm LW}$, see above). Numerical studies in this vein (e.g., Shang et al. Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Van Borm, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2014c) suggest that it is indeed possible to almost completely dissociate

$J_{\rm LW}$, see above). Numerical studies in this vein (e.g., Shang et al. Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Van Borm, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2014c) suggest that it is indeed possible to almost completely dissociate ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ (and therefore suppress ‘normal’ Pop III star formation) in primordial halos, requiring however very high values of the Lyman-Werner (LW)-specific intensity (with the extent of the problem particularly dependent on the assumed spectrum, see below).

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ (and therefore suppress ‘normal’ Pop III star formation) in primordial halos, requiring however very high values of the Lyman-Werner (LW)-specific intensity (with the extent of the problem particularly dependent on the assumed spectrum, see below).

In addition to near-UV photons, stellar radiation in the infrared (IR) can also provide an important contribution to feedback in the early Universe (Wolcott-Green & Haiman Reference Wolcott-Green and Haiman2012). In particular, photons in the energy range ![]() $h\nu \geq 0.76\,\mathrm{eV}$ can unbind the extra electron in

$h\nu \geq 0.76\,\mathrm{eV}$ can unbind the extra electron in ![]() $\mathrm{H}^{-}$, which otherwise catalyses

$\mathrm{H}^{-}$, which otherwise catalyses ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ formation at low densities via the reactions:

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ formation at low densities via the reactions:

thus playing a key role in determining the equilibrium ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction. Therefore, cooler low-mass stars (in particular, second generation ‘Pop II’ stars) can also play an important role in regulating early star formation.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction. Therefore, cooler low-mass stars (in particular, second generation ‘Pop II’ stars) can also play an important role in regulating early star formation. ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ formation can also be catalysed via the reaction chain

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ formation can also be catalysed via the reaction chain

$$\eqalign{

& {{\rm{H}}^{\rm{ + }}}{\rm{ + }}\,{\rm{H }} \to {\rm{ H}}_{\rm{2}}^{\rm{ + }}{\rm{ + }}\gamma , \cr

& {\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}^{\rm{ + }}{\rm{ + H}} \to {{\rm{H}}_2}{\rm{ + }}{{\rm{H}}^{\rm{ + }}}. \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{

& {{\rm{H}}^{\rm{ + }}}{\rm{ + }}\,{\rm{H }} \to {\rm{ H}}_{\rm{2}}^{\rm{ + }}{\rm{ + }}\gamma , \cr

& {\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}^{\rm{ + }}{\rm{ + H}} \to {{\rm{H}}_2}{\rm{ + }}{{\rm{H}}^{\rm{ + }}}. \cr} $$

However, this is considerably less effective than forming ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ via the

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ via the ![]() $\mathrm{H}^{-}$ ion, and so these reactions play an important role in SMS formation only in unusual circumstances (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Coppola, Omukai, Galli and Palla2016).

$\mathrm{H}^{-}$ ion, and so these reactions play an important role in SMS formation only in unusual circumstances (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Coppola, Omukai, Galli and Palla2016).

Taking all this together, the photodetachment of ![]() $\mathrm{H}^{-}$ and the photo-dissociation of

$\mathrm{H}^{-}$ and the photo-dissociation of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ may be parametrised as

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ may be parametrised as

where ![]() $C_{\rm di} = 1.38\times10^{-12}\ \rm s^{-1}$ and

$C_{\rm di} = 1.38\times10^{-12}\ \rm s^{-1}$ and ![]() $C_{\rm de} = 1.1\times 10^{-10}\ \rm s^{-1}$ are rate constants, α and

$C_{\rm de} = 1.1\times 10^{-10}\ \rm s^{-1}$ are rate constants, α and ![]() $\beta$ are rate parameters that depend on the spectral shape of the irradiating source, and

$\beta$ are rate parameters that depend on the spectral shape of the irradiating source, and ![]() $J_{\rm{LW}}$ is the LW-specific intensity, as defined earlier. Therefore, it is essential that both the spectral shape of the irradiating source(s) and their specific intensity be accounted for in modelling the equilibrium

$J_{\rm{LW}}$ is the LW-specific intensity, as defined earlier. Therefore, it is essential that both the spectral shape of the irradiating source(s) and their specific intensity be accounted for in modelling the equilibrium ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction in primordial halos.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction in primordial halos.

2.1.2. Is there a single critical Lyman–Werner flux?

Much of the work that has been done to investigate the impact of radiation from the earliest star forming systems on the later collapse of primordial gas has adopted a highly simplified description of the spectral energy distribution (SED) of the radiation, often describing it in terms of a single temperature black body or a power-law spectrum. In particular, the use of a ![]() $T = 10^{5}\,\mathrm{K}$ black body spectrum (hereafter a T5 spectrum) to model emission from Pop III dominated systems and a

$T = 10^{5}\,\mathrm{K}$ black body spectrum (hereafter a T5 spectrum) to model emission from Pop III dominated systems and a ![]() $T = 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ black body spectrum (hereafter a T4 spectrum) to model emission from Pop II dominated systems is particularly common, although some studies have also considered black-body spectra with intermediate temperatures (Sugimura, Omukai, & Inoue Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015).

$T = 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ black body spectrum (hereafter a T4 spectrum) to model emission from Pop II dominated systems is particularly common, although some studies have also considered black-body spectra with intermediate temperatures (Sugimura, Omukai, & Inoue Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015).

The earliest study to examine the impact of extremely large levels of incident Lyman–Werner radiation on the gravitational collapse of primordial gas was carried out by Omukai (Reference Omukai2001).Footnote a He showed that for a sufficiently large incident flux, ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling could be completely suppressed in the collapsing gas. In its absence, cooling from Lyman-α and Balmer series emission and from processes such as

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling could be completely suppressed in the collapsing gas. In its absence, cooling from Lyman-α and Balmer series emission and from processes such as ![]() $\mathrm{H}^{-}$ formation results in a quasi-isothermal collapse of the gas at a temperature

$\mathrm{H}^{-}$ formation results in a quasi-isothermal collapse of the gas at a temperature ![]() $T \sim 7\,000\,\mathrm{K}$, dropping only gradually with increasing density, thereby leading to a very high Jeans mass of

$T \sim 7\,000\,\mathrm{K}$, dropping only gradually with increasing density, thereby leading to a very high Jeans mass of ![]() ${\sim} 10^{6}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$ at

${\sim} 10^{6}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$ at ![]() $n \sim 10^{3}\,{\rm cm}^{-3}$. In a low-mass dark matter minihalo, where the total gas reservoir often does not exceed this value, this would be enough to completely suppress the collapse of the gas. However, in an atomic cooling halo with a virial temperature

$n \sim 10^{3}\,{\rm cm}^{-3}$. In a low-mass dark matter minihalo, where the total gas reservoir often does not exceed this value, this would be enough to completely suppress the collapse of the gas. However, in an atomic cooling halo with a virial temperature ![]() $T_{\rm vir} \sim 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ and with a much larger gas reservoir, collapse would not be suppressed. However, this high temperature would inhibit fragmentation, which leads to the idea that in such systems the gas may collapse directly without fragmenting to form a single SMS (or quasi-star) with a mass of

$T_{\rm vir} \sim 10^{4}\,\mathrm{K}$ and with a much larger gas reservoir, collapse would not be suppressed. However, this high temperature would inhibit fragmentation, which leads to the idea that in such systems the gas may collapse directly without fragmenting to form a single SMS (or quasi-star) with a mass of ![]() $10^{4}$–

$10^{4}$–![]() $10^{5}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$.

$10^{5}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$.

A key parameter in this scenario is the strength of the Lyman–Werner radiation field required in order to suppress ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling, commonly referred to as

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling, commonly referred to as ![]() $J_{\rm{ crit}}$. The earliest studies (Omukai Reference Omukai2001; Bromm & Loeb Reference Bromm and Loeb2003) found that extremely high values of

$J_{\rm{ crit}}$. The earliest studies (Omukai Reference Omukai2001; Bromm & Loeb Reference Bromm and Loeb2003) found that extremely high values of ![]() $J_{\rm {crit}}$ were required, but Shang et al. (Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010) later showed that this was a consequence of the simplified treatment of

$J_{\rm {crit}}$ were required, but Shang et al. (Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010) later showed that this was a consequence of the simplified treatment of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ collisional dissociation adopted in these studies, and that simulations with a more accurate treatment of this process yielded significantly lower values for

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ collisional dissociation adopted in these studies, and that simulations with a more accurate treatment of this process yielded significantly lower values for ![]() $J_{\rm {crit}}$. The issue of the correct value of

$J_{\rm {crit}}$. The issue of the correct value of ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ has subsequently been addressed by a number of other authors, but despite this considerable uncertainties remain. Single-zone models of the thermal and chemical evolution of the gas, similar to those studied by Omukai (Reference Omukai2001), typically find

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ has subsequently been addressed by a number of other authors, but despite this considerable uncertainties remain. Single-zone models of the thermal and chemical evolution of the gas, similar to those studied by Omukai (Reference Omukai2001), typically find ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 10$ for a T4 spectrum and

$J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 10$ for a T4 spectrum and ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 1\,000$ for a T5 spectrum (see, e.g., Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Glover Reference Glover2015a).Footnote b However, there is a factor of 2–3 uncertainty in these values that arises from uncertainties in the input rate coefficient data (Glover Reference Glover2015b). In addition, there may be as much as an order of magnitude uncertainty arising from how

$J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 1\,000$ for a T5 spectrum (see, e.g., Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Glover Reference Glover2015a).Footnote b However, there is a factor of 2–3 uncertainty in these values that arises from uncertainties in the input rate coefficient data (Glover Reference Glover2015b). In addition, there may be as much as an order of magnitude uncertainty arising from how ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ self-shielding is treated (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Glover Reference Glover2015b), with different self-shielding prescriptions yielding substantially different results.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ self-shielding is treated (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Glover Reference Glover2015b), with different self-shielding prescriptions yielding substantially different results.

In addition, three-dimensional simulations of the collapse of highly irradiated primordial gas typically find values of ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ that are much larger than those found in one-zone models, with

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ that are much larger than those found in one-zone models, with ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 400$ for a T4 spectrum and

$J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 400$ for a T4 spectrum and ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 10^{4}$ for a T5 spectrum (Shang et al. Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010; Regan, Johansson, & Haehnelt Reference Regan, Johansson and Haehnelt2014; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015). The significant difference between one-zone and 3D model predictions for the value of

$J_{\rm{crit}} \sim 10^{4}$ for a T5 spectrum (Shang et al. Reference Shang, Bryan and Haiman2010; Regan, Johansson, & Haehnelt Reference Regan, Johansson and Haehnelt2014; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015). The significant difference between one-zone and 3D model predictions for the value of ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ is not completely understood, but may be a consequence of the large number of weak shocks that one finds in the 3D models, which produce a pervasive low level of ionisation in the collapsing gas that is missing in the one-zone models.

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ is not completely understood, but may be a consequence of the large number of weak shocks that one finds in the 3D models, which produce a pervasive low level of ionisation in the collapsing gas that is missing in the one-zone models.

Additional uncertainties arise once one considers other sources of radiation. For example, if a high redshift X-ray background is present, then this can significantly increase ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ if the strength of the X-ray background is high enough (Inayoshi & Omukai Reference Inayoshi and Omukai2011; Inayoshi & Tanaka Reference Inayoshi and Tanaka2015; Glover Reference Glover2016), although the effect is much greater in one-zone models than in 3D models (Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015). Accounting for H− detachment by the Lyman-α photons produced during the collapse of the gas can also lead to a factor of a few reduction in

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ if the strength of the X-ray background is high enough (Inayoshi & Omukai Reference Inayoshi and Omukai2011; Inayoshi & Tanaka Reference Inayoshi and Tanaka2015; Glover Reference Glover2016), although the effect is much greater in one-zone models than in 3D models (Latif et al. Reference Latif, Bovino, Grassi, Schleicher and Spaans2015). Accounting for H− detachment by the Lyman-α photons produced during the collapse of the gas can also lead to a factor of a few reduction in ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$, potentially corresponding to up to a ~100-fold increase in the anticipated number density of DCBHs (Johnson & Dijkstra Reference Johnson and Dijkstra2017).

$J_{\rm{crit}}$, potentially corresponding to up to a ~100-fold increase in the anticipated number density of DCBHs (Johnson & Dijkstra Reference Johnson and Dijkstra2017).

Using a single black body spectrum to represent the integrated light from all of the stars in a galaxy is, however, a very crude approximation. A more realistic treatment necessitates incorporating more detailed models for SEDs from either single (Starburst99, Leitherer et al. Reference Leitherer1999), or more recently available binary (BPASS, Eldridge & Stanway Reference Eldridge and Stanway2016) stellar population and spectral synthesis codes. This allows one to compute the rate parameters α and β for models of early stellar populations as a function of stellar mass, star formation rate (SFR), metallicity (Z), and age of the stellar population. Carrying out this analysis, Agarwal and Khochfar (Reference Agarwal and Khochfar2015) and Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Cullen, Khochfar, Klessen, Glover and Johnson2017a) found that α and β, and therefore ![]() $k_{\rm de}$ and

$k_{\rm de}$ and ![]() $k_{\rm di}$, vary over several orders of magnitude during the lifetime of an instantaneous burst of star formation, though less than an order of magnitude for a continuous SFR. This implies that for galaxies with realistic spectra, one cannot summarise the effects of their radiation with a single

$k_{\rm di}$, vary over several orders of magnitude during the lifetime of an instantaneous burst of star formation, though less than an order of magnitude for a continuous SFR. This implies that for galaxies with realistic spectra, one cannot summarise the effects of their radiation with a single ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ parameter, since the value of this will depend on α and β, and hence on the properties of the individual stellar populations. Instead, the radiation constraint for DCBH formation can be better understood in terms of the interplay between

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ parameter, since the value of this will depend on α and β, and hence on the properties of the individual stellar populations. Instead, the radiation constraint for DCBH formation can be better understood in terms of the interplay between ![]() $k_{\rm de}$ and

$k_{\rm de}$ and ![]() $k_{\rm di}$.

$k_{\rm di}$.

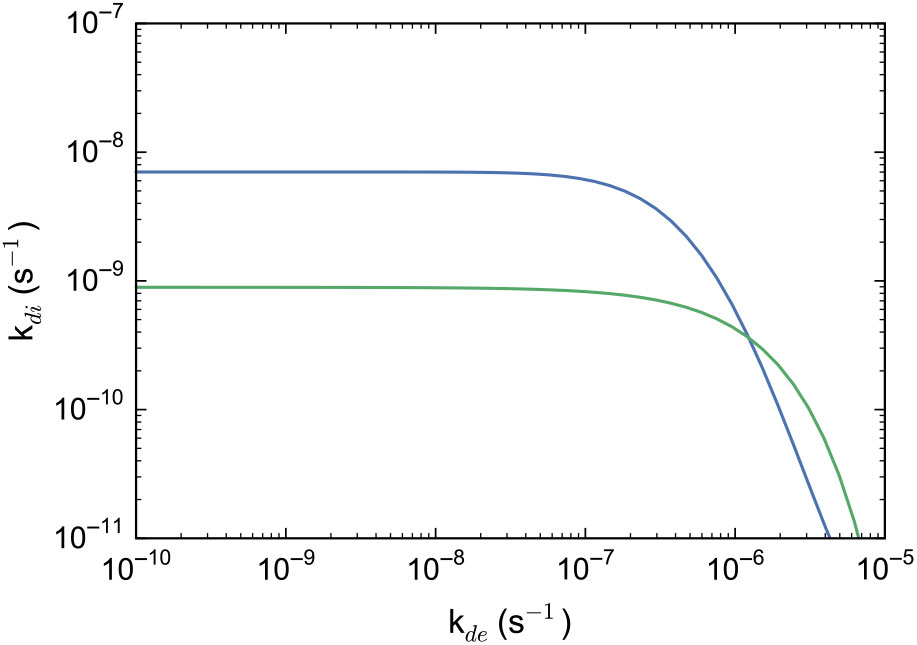

A particularly useful way to express the radiation constraint (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a; Wolcott-Green et al. Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017) is in the form of a critical curve in the ![]() $k_{\rm de}$–

$k_{\rm de}$–![]() $k_{\rm di}$ parameter space (see Figure 2) which separates those sets of reaction rates that lead to efficient

$k_{\rm di}$ parameter space (see Figure 2) which separates those sets of reaction rates that lead to efficient ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling and fragmentation from those that lead to the suppression of

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling and fragmentation from those that lead to the suppression of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling and SMS formation. This curve is a consequence of the chemo-thermal evolution of the irradiated gas, and although it is affected by many of the same uncertainties that hamper our efforts to determine

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling and SMS formation. This curve is a consequence of the chemo-thermal evolution of the irradiated gas, and although it is affected by many of the same uncertainties that hamper our efforts to determine ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ for idealised spectra, it has the significant advantage that it does not depend on the spectral properties of the source of the radiation. We can therefore study what types of sources are likely to lead to the suppression of

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ for idealised spectra, it has the significant advantage that it does not depend on the spectral properties of the source of the radiation. We can therefore study what types of sources are likely to lead to the suppression of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling by examining where the photochemical rates produced by different sources lie with respect to this critical curve.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling by examining where the photochemical rates produced by different sources lie with respect to this critical curve.

Figure 2. The critical curve(s) in ![]() $k_{\rm de}$–

$k_{\rm de}$–![]() $k_{\rm di}$ phase space, characterising the photo-detachment of H− and the photo-dissociation of

$k_{\rm di}$ phase space, characterising the photo-detachment of H− and the photo-dissociation of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ in an irradiated halo (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a; Wolcott-Green, Haiman, & Bryan Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017). Each curve divides the parameter space into two regions, depending on the equilibrium

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ in an irradiated halo (Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a; Wolcott-Green, Haiman, & Bryan Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017). Each curve divides the parameter space into two regions, depending on the equilibrium ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction resulting from the given values of

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction resulting from the given values of ![]() $k_{\rm de}$ and

$k_{\rm de}$ and ![]() $k_{\rm di}$. Rates above the curve lead to collapse into a DCBH and below result in fragmentation into Pop III stars. The difference between the curves is due to the difference in the Jeans length and self-shielding of

$k_{\rm di}$. Rates above the curve lead to collapse into a DCBH and below result in fragmentation into Pop III stars. The difference between the curves is due to the difference in the Jeans length and self-shielding of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$. The blue curve (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a) is obtained with a Jeans length that is twice that of the one used in the green curve (Wolcott-Green et al. Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017).

${\rm{H}}_{2}$. The blue curve (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a) is obtained with a Jeans length that is twice that of the one used in the green curve (Wolcott-Green et al. Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017).

In summary, no single-valued critical Lyman–Werner intensity ![]() $J_{\rm{crit}}$ appears to provide a suitable criterion for the formation of an atomically cooled halo under arbitrary circumstances. Alternative prescriptions based on the availability and photo-destruction of relevant species, such as that formulated by Sugimura et al. (Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014), Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a), and Wolcott-Green et al. (Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017), are more useful for understanding the equilibrium

$J_{\rm{crit}}$ appears to provide a suitable criterion for the formation of an atomically cooled halo under arbitrary circumstances. Alternative prescriptions based on the availability and photo-destruction of relevant species, such as that formulated by Sugimura et al. (Reference Sugimura, Omukai and Inoue2014), Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Smith, Glover, Natarajan and Khochfar2016a), and Wolcott-Green et al. (Reference Wolcott-Green, Haiman and Bryan2017), are more useful for understanding the equilibrium ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction in primordial halos irradiated by an external Lyman–Werner flux. Whether this irradiation provides the primary catalyst for DCBH formation remains an open question, with recent results adding further evidence that, e.g., structure formation dynamics may in fact play a more significant role (Wise et al. Reference Wise, Regan, O’Shea, Norman, Downes and Xu2019). This and other complicating factors are addressed in the following sections.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ fraction in primordial halos irradiated by an external Lyman–Werner flux. Whether this irradiation provides the primary catalyst for DCBH formation remains an open question, with recent results adding further evidence that, e.g., structure formation dynamics may in fact play a more significant role (Wise et al. Reference Wise, Regan, O’Shea, Norman, Downes and Xu2019). This and other complicating factors are addressed in the following sections.

2.2. Fragmentation

One of the key requirements for the formation of a supermassive primordial star (SMS) with ![]() $M_\star \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 10^5~{\rm M}_\odot$ is to suppress vigorous fragmentation of its parent gas cloud. It is anticipated that for a nearly isothermal cloud in an atomic-cooling halo, where

$M_\star \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\gt\over

{\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 10^5~{\rm M}_\odot$ is to suppress vigorous fragmentation of its parent gas cloud. It is anticipated that for a nearly isothermal cloud in an atomic-cooling halo, where ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ is dissociated by intense LW radiation and/or collisions with atomic hydrogen (see the previous section), the gas undergoes monolithic collapse without a major episode of fragmentation. Significant progress has been made in the past decade to understand the details of isothermal collapse of such an

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ is dissociated by intense LW radiation and/or collisions with atomic hydrogen (see the previous section), the gas undergoes monolithic collapse without a major episode of fragmentation. Significant progress has been made in the past decade to understand the details of isothermal collapse of such an ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$-free gas in atomic cooling halos, both via analytical frameworks and numerical simulations. Three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations show that the gas cloud is unlikely to fragment into gravitationally bound clumps during the runaway collapse phase and forms a central protostar surrounding a massive accretion disk (Latif et al. Reference Latif, Schleicher, Schmidt and Niemeyer2013b; Inayoshi, Omukai, & Tasker Reference Inayoshi, Omukai and Tasker2014; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Greif, Springel and Hernquist2015).

${\rm{H}}_{2}$-free gas in atomic cooling halos, both via analytical frameworks and numerical simulations. Three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations show that the gas cloud is unlikely to fragment into gravitationally bound clumps during the runaway collapse phase and forms a central protostar surrounding a massive accretion disk (Latif et al. Reference Latif, Schleicher, Schmidt and Niemeyer2013b; Inayoshi, Omukai, & Tasker Reference Inayoshi, Omukai and Tasker2014; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Greif, Springel and Hernquist2015).

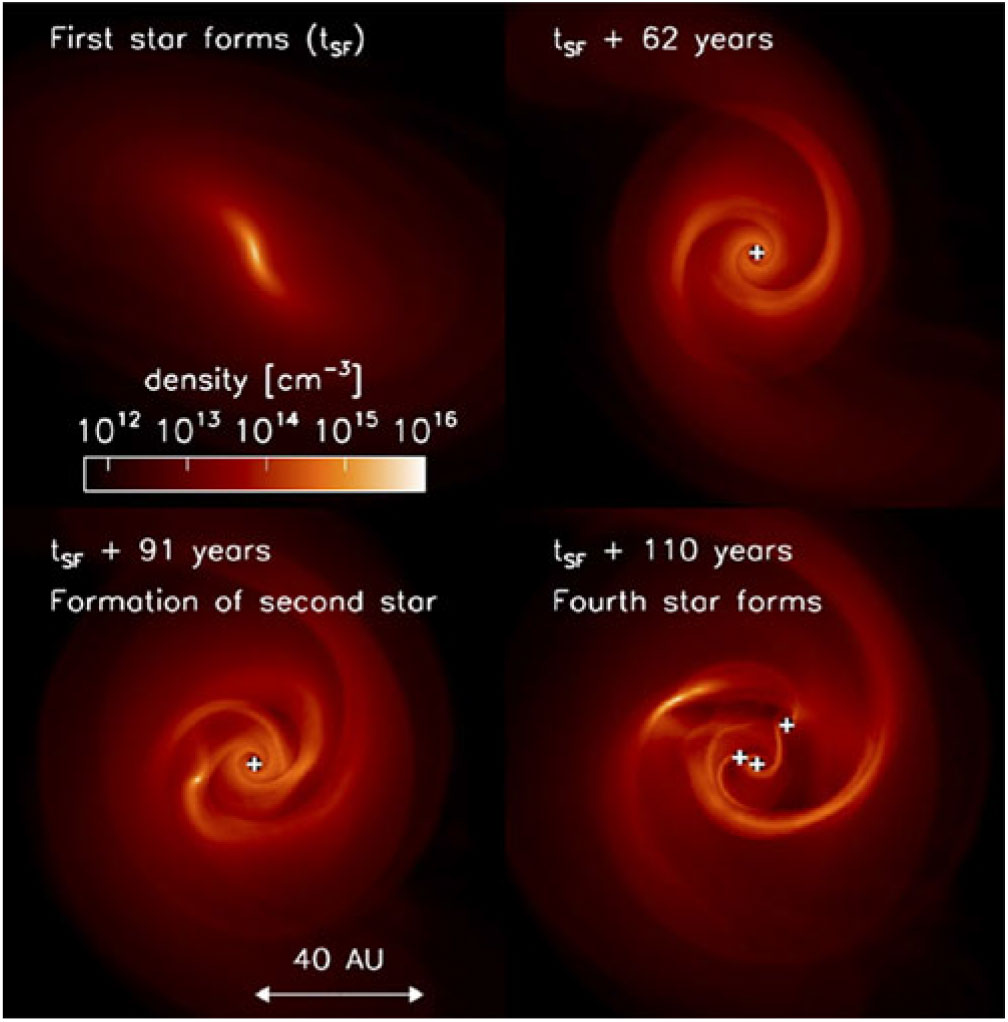

However, as material falls in, conservation of angular momentum leads to the build-up of a centrifugally supported accretion disk. As the disk grows in mass it may become gravitationally unstable, fragment, and form multiple objects (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Glover, Smith, Greif, Klessen and Bromm2011a, Reference Clark, Glover, Klessen and Bromm2011b; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Glover, Clark, Greif and Klessen2011; Greif et al. Reference Greif, Bromm, Clark, Glover, Smith, Klessen, Yoshida and Springel2012; Regan et al. Reference Regan, Johansson and Haehnelt2014; Sakurai et al. Reference Sakurai, Vorobyov, Hosokawa, Yoshida, Omukai and Yorke2016). This is illustrated in Figure 3 for the case of an ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ dominated disk which will form normal-mass Pop III stars. High resolution simulations suggest that fragmentation mostly occurs within the central parsec, but may also happen on larger scales in some cases, depending on the larger environment, merger history, spin, and so forth. Even if fragmentation occurs within the disk on small scales, many clumps may eventually migrate inward and merge with the central protostar. This is because the migration timescale in a self-gravitating disk is as short as the orbital timescale (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Glover, Smith, Greif, Klessen and Bromm2011a; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Hosokawa, Omukai, Glover and Klessen2012; Inayoshi & Haiman Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014; Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015a). This leads to intermittent mass accretion onto the central object, with mass inflow rates up to

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ dominated disk which will form normal-mass Pop III stars. High resolution simulations suggest that fragmentation mostly occurs within the central parsec, but may also happen on larger scales in some cases, depending on the larger environment, merger history, spin, and so forth. Even if fragmentation occurs within the disk on small scales, many clumps may eventually migrate inward and merge with the central protostar. This is because the migration timescale in a self-gravitating disk is as short as the orbital timescale (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Glover, Smith, Greif, Klessen and Bromm2011a; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Hosokawa, Omukai, Glover and Klessen2012; Inayoshi & Haiman Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014; Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015a). This leads to intermittent mass accretion onto the central object, with mass inflow rates up to ![]() $0.1~{\rm M}_{\odot}~{\rm yr}^{-1}$ or more (Sakurai et al. Reference Sakurai, Vorobyov, Hosokawa, Yoshida, Omukai and Yorke2016; Latif, Schleicher, & Hartwig Reference Latif, Schleicher and Hartwig2016b; Regan & Downes Reference Regan and Downes2018a; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Marinacci, Inayoshi, Bromm and Hernquist2018). In some cases, tidal force caused by nearby galaxies strongly influences the morphology of a massive

$0.1~{\rm M}_{\odot}~{\rm yr}^{-1}$ or more (Sakurai et al. Reference Sakurai, Vorobyov, Hosokawa, Yoshida, Omukai and Yorke2016; Latif, Schleicher, & Hartwig Reference Latif, Schleicher and Hartwig2016b; Regan & Downes Reference Regan and Downes2018a; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Marinacci, Inayoshi, Bromm and Hernquist2018). In some cases, tidal force caused by nearby galaxies strongly influences the morphology of a massive ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cloud that potentially forms an SMS, leading to the potential formation of a smaller cluster of SMSs under a strong tidal field (Chon et al. Reference Chon, Hirano, Hosokawa and Yoshida2016; Chon, Hosokawa, & Yoshida Reference Chon, Hosokawa and Yoshida2018). Clearly, this area requires further attention.

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cloud that potentially forms an SMS, leading to the potential formation of a smaller cluster of SMSs under a strong tidal field (Chon et al. Reference Chon, Hirano, Hosokawa and Yoshida2016; Chon, Hosokawa, & Yoshida Reference Chon, Hosokawa and Yoshida2018). Clearly, this area requires further attention.

Figure 3. Fragmentation of the accretion disk in the centre of a primordial halo for conditions leading to the formation of normal-mass Pop III stars. The image is adopted from Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Glover, Smith, Greif, Klessen and Bromm2011a).

The efficiency of fragmentation depends strongly on the thermal evolution of the gas (Klessen & Glover Reference Klessen and Glover2016), and so an adequate description requires one to take into account all relevant processes regarding radiative cooling and chemical reactions. For this purpose, recent simulations have employed detailed chemical models in order to explore the impact of H− cooling (![]() ${\rm H}+{\rm e}^- \rightarrow {\rm H}^- + \gamma$;

${\rm H}+{\rm e}^- \rightarrow {\rm H}^- + \gamma$; ![]() ${\rm H}+{\rm e}^- \rightarrow {\rm H} + {\rm e}^- +\gamma$), and opacities due to H− bound-free/free-free transition and Rayleigh scattering of hydrogen atoms. In fact, H− cooling decreases the temperature with increasing density, i.e.,

${\rm H}+{\rm e}^- \rightarrow {\rm H} + {\rm e}^- +\gamma$), and opacities due to H− bound-free/free-free transition and Rayleigh scattering of hydrogen atoms. In fact, H− cooling decreases the temperature with increasing density, i.e., ![]() $\gamma_{\rm eff} {\lt}1$, where

$\gamma_{\rm eff} {\lt}1$, where ![]() $\gamma_{\rm eff}$ is the specific heat index (

$\gamma_{\rm eff}$ is the specific heat index (![]() $P\propto \rho^{\gamma_{\rm eff}}$). Based on linear stability analysis, a runaway-collapsing cloud, the so-called Larson–Penston self-similar solution (Larson Reference Larson1969), is unstable against non-spherical perturbations when

$P\propto \rho^{\gamma_{\rm eff}}$). Based on linear stability analysis, a runaway-collapsing cloud, the so-called Larson–Penston self-similar solution (Larson Reference Larson1969), is unstable against non-spherical perturbations when ![]() $\gamma_{\rm eff}\mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\lt\over {\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 1.1$. As a result, the collapsing region is elongated with the density and fragments into clumps (Lai Reference Lai2000; Hanawa & Matsumoto Reference Hanawa and Matsumoto2000; Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Mizuno, Matsumoto and Omukai2017). However, since the growth timescale is sufficiently long, turbulence in the collapsing gas would suppress the unstable modes. On the other hand, when the density increases to

$\gamma_{\rm eff}\mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel\lt\over {\smash{\scriptstyle\sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 1.1$. As a result, the collapsing region is elongated with the density and fragments into clumps (Lai Reference Lai2000; Hanawa & Matsumoto Reference Hanawa and Matsumoto2000; Sugimura et al. Reference Sugimura, Mizuno, Matsumoto and Omukai2017). However, since the growth timescale is sufficiently long, turbulence in the collapsing gas would suppress the unstable modes. On the other hand, when the density increases to ![]() ${\simeq} 10^6$–

${\simeq} 10^6$–![]() $10^{13}~{\rm cm}^{-3}$, cold clumps with

$10^{13}~{\rm cm}^{-3}$, cold clumps with ![]() $T\sim 10^3\,\mathrm{K}$ are produced by the thermal instability induced by the combination of the adiabatic cooling due to turbulent expansion and the subsequent H− and

$T\sim 10^3\,\mathrm{K}$ are produced by the thermal instability induced by the combination of the adiabatic cooling due to turbulent expansion and the subsequent H− and ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014). Since the cold clumps are not massive enough to be gravitationally bound, the evolution of the central collapsing region is not affected. We note that the thermal instability would play an important role after a rotationally supported disk forms at the centre because the gravitational collapse is significantly delayed. A similar outcome is observed in less conventional direct collapse scenarios, such as in the simulations of multi-scale inflows driven by mergers between massive galaxies at

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014). Since the cold clumps are not massive enough to be gravitationally bound, the evolution of the central collapsing region is not affected. We note that the thermal instability would play an important role after a rotationally supported disk forms at the centre because the gravitational collapse is significantly delayed. A similar outcome is observed in less conventional direct collapse scenarios, such as in the simulations of multi-scale inflows driven by mergers between massive galaxies at ![]() $z \sim $ 8–10 (Mayer & Bonoli Reference Mayer and Bonoli2018). In the latter case, gas is already metal-enriched but the extremely high optical depth in the inner regions relegates rapid cooling and sporadic fragmentation into transient clumps just to the outer rims of the disk.

$z \sim $ 8–10 (Mayer & Bonoli Reference Mayer and Bonoli2018). In the latter case, gas is already metal-enriched but the extremely high optical depth in the inner regions relegates rapid cooling and sporadic fragmentation into transient clumps just to the outer rims of the disk.

At densities above ![]() $\rm 10^{16} ~cm^{-3}$, the central region becomes opaque to all radiative processes and the temperature rises above

$\rm 10^{16} ~cm^{-3}$, the central region becomes opaque to all radiative processes and the temperature rises above ![]() $\rm 10^4$ K (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi, Omukai and Tasker2014; Van Borm et al. Reference Van Borm, Bovino, Latif, Schleicher, Spaans and Grassi2014; Latif et al. Reference Habouzit, Volonteri, Latif, Dubois and Peirani2016b; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Marinacci, Inayoshi, Bromm and Hernquist2018). The opaque core (i.e., protostar) further increases the density and temperature adiabatically via mass accretion from the surrounding material. Due to the rapid input of high-entropy material, the central protostar evolves with an expanding envelope during the earliest stages of gas accretion (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014) (see also Section 3). In the late phase, gas supply onto the protostar is dominated by episodic bursts because the surrounding accretion disk is unstable against its self-gravity, forming multiple fragments. In the quiescent phases of the episodic accretion, the protostar contracts via radiative diffusion and starts to emit ionising photons. Chon et al. (Reference Chon, Hosokawa and Yoshida2018) found that even though the ionising photons produced from the proto-SMS heats the surrounding gas, the feedback effect cannot reverse the gas inflow to the centre. This is in line with results from radiation hydrodynamic simulations of present-day star formation (see, e.g., Krumholz et al. Reference Krumholz, Klein, McKee, Offner and Cunningham2009; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Mac Low, Banerjee, Klessen and Dullemond2010, Reference Peters, Banerjee, Klessen and Mac Low2011; Kuiper et al. Reference Kuiper, Klahr, Beuther and Henning2011). However, radiative heating can reduce the level of disk fragmentation, and so further numerical simulations with a high spatial resolution and multi-frequency radiative transfer are required to fully quantify this effect. In addition, studies with a larger sample of halos in a cosmological volume will allow us to address the fate of gas collapse, fragmentation, and formation of SMSs in atomic-cooling halos.

$\rm 10^4$ K (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi, Omukai and Tasker2014; Van Borm et al. Reference Van Borm, Bovino, Latif, Schleicher, Spaans and Grassi2014; Latif et al. Reference Habouzit, Volonteri, Latif, Dubois and Peirani2016b; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Marinacci, Inayoshi, Bromm and Hernquist2018). The opaque core (i.e., protostar) further increases the density and temperature adiabatically via mass accretion from the surrounding material. Due to the rapid input of high-entropy material, the central protostar evolves with an expanding envelope during the earliest stages of gas accretion (Inayoshi et al. Reference Inayoshi and Haiman2014) (see also Section 3). In the late phase, gas supply onto the protostar is dominated by episodic bursts because the surrounding accretion disk is unstable against its self-gravity, forming multiple fragments. In the quiescent phases of the episodic accretion, the protostar contracts via radiative diffusion and starts to emit ionising photons. Chon et al. (Reference Chon, Hosokawa and Yoshida2018) found that even though the ionising photons produced from the proto-SMS heats the surrounding gas, the feedback effect cannot reverse the gas inflow to the centre. This is in line with results from radiation hydrodynamic simulations of present-day star formation (see, e.g., Krumholz et al. Reference Krumholz, Klein, McKee, Offner and Cunningham2009; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Mac Low, Banerjee, Klessen and Dullemond2010, Reference Peters, Banerjee, Klessen and Mac Low2011; Kuiper et al. Reference Kuiper, Klahr, Beuther and Henning2011). However, radiative heating can reduce the level of disk fragmentation, and so further numerical simulations with a high spatial resolution and multi-frequency radiative transfer are required to fully quantify this effect. In addition, studies with a larger sample of halos in a cosmological volume will allow us to address the fate of gas collapse, fragmentation, and formation of SMSs in atomic-cooling halos.

So far, the main focus of these studies has been on understanding the isothermal collapse and its implications for the formation of an SMS. This scenario demands rather special conditions and mandates that the halo should be metal free and the formation of ![]() $\rm H_2$ remains suppressed (see previous section for details). These requirements make the sites of SMSs less abundant if not rare but this is still an open question. However, less idealised conditions such as halos polluted with trace amount of metals

$\rm H_2$ remains suppressed (see previous section for details). These requirements make the sites of SMSs less abundant if not rare but this is still an open question. However, less idealised conditions such as halos polluted with trace amount of metals ![]() $Z/{\rm Z}_{\odot} \leq 10^{-5}$, halos irradiated by a moderate strength UV flux below the critical limit, or halos with large baryonic streaming velocities (see the following, dedicated subsection on this topic) may still form an SMS (Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015b; Latif et al. Reference Habouzit, Volonteri, Latif, Dubois and Peirani2016b; Hirano et al. Reference Hirano, Hosokawa, Yoshida and Kuiper2017; Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017; Inayoshi, Li, & Haiman Reference Visbal and Haiman2018).

$Z/{\rm Z}_{\odot} \leq 10^{-5}$, halos irradiated by a moderate strength UV flux below the critical limit, or halos with large baryonic streaming velocities (see the following, dedicated subsection on this topic) may still form an SMS (Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015b; Latif et al. Reference Habouzit, Volonteri, Latif, Dubois and Peirani2016b; Hirano et al. Reference Hirano, Hosokawa, Yoshida and Kuiper2017; Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017; Inayoshi, Li, & Haiman Reference Visbal and Haiman2018).

In fact, halos irradiated by a moderate UV flux of strength ![]() $\sim 1\,000 J_{21}$ can still provide large inflow rates of

$\sim 1\,000 J_{21}$ can still provide large inflow rates of ![]() ${\sim} 0.1\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}\,\mathrm{yr}^{-1}$, sufficient to produce an SMS (Hosokawa, Omukai, & Yorke Reference Hosokawa, Omukai and Yorke2012; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Schleicher, Bovino, Grassi and Spaans2014d; Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015b; Regan & Downes Reference Regan and Downes2018a). Under these conditions, gas remains hot with a temperature

${\sim} 0.1\,\mathrm{M}_{\odot}\,\mathrm{yr}^{-1}$, sufficient to produce an SMS (Hosokawa, Omukai, & Yorke Reference Hosokawa, Omukai and Yorke2012; Latif et al. Reference Latif, Schleicher, Bovino, Grassi and Spaans2014d; Latif & Schleicher Reference Latif and Schleicher2015b; Regan & Downes Reference Regan and Downes2018a). Under these conditions, gas remains hot with a temperature ![]() $\sim8\,000\,\mathrm{K}$ at scales above

$\sim8\,000\,\mathrm{K}$ at scales above ![]() ${\sim}1$ parsec, similar to the isothermal case, while in the core of the halo sufficient

${\sim}1$ parsec, similar to the isothermal case, while in the core of the halo sufficient ![]() $\rm H_2$ can form to allow the temperature to fall to a few hundred K. Similar conditions are observed for halos irradiated by an intense UV flux, but polluted with trace amounts of metals (

$\rm H_2$ can form to allow the temperature to fall to a few hundred K. Similar conditions are observed for halos irradiated by an intense UV flux, but polluted with trace amounts of metals (![]() $Z/\mathrm{Z}_{\odot} \leq 10^{-5}$). For further discussion regarding the role of streaming motions in the birth of SMS, see the following subsection.

$Z/\mathrm{Z}_{\odot} \leq 10^{-5}$). For further discussion regarding the role of streaming motions in the birth of SMS, see the following subsection.

Less idealised conditions are more prone to fragmentation on scales below 1 pc, but clump migration in combination with dynamical/viscous heating at these scales stabilises the disk. Therefore, conditions still seem conducive for the formation of a massive central object. Unfortunately, a better understanding of these conditions is still limited due to the computational constraints; however, they may provide a potential pathway for the formation of SMSs at ![]() $z {\gt} 10$.

$z {\gt} 10$.

2.3. Streaming velocities

Before recombination, baryons and photons are tightly coupled. This leads to acoustic waves (Sunyaev & Zel’dovich Reference Sunyaev and Zel’dovich1970) that also result in oscillations between baryons and dark matter. At ![]() $z \approx 1\,000$ the relative velocities are

$z \approx 1\,000$ the relative velocities are ![]() ${\sim} 30\,$km

${\sim} 30\,$km![]() $\,\textit{s}^{-1}$, with coherence lengths of several 10–100 Mpc (Silk Reference Silk1986; Tseliakhovich & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich and Hirata2010b). This streaming velocity decays linearly with z and reaches values of about 1 km

$\,\textit{s}^{-1}$, with coherence lengths of several 10–100 Mpc (Silk Reference Silk1986; Tseliakhovich & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich and Hirata2010b). This streaming velocity decays linearly with z and reaches values of about 1 km![]() $\,\textit{s}^{-1}$ at a redshift of

$\,\textit{s}^{-1}$ at a redshift of ![]() $z \approx 30$. It is thus comparable to the virial velocity of the first halos to cool and collapse, and has the potential to strongly influence gas dynamics and star formation within these halos (Tseliakhovich, Barkana, & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich, Barkana and Hirata2011; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012).

$z \approx 30$. It is thus comparable to the virial velocity of the first halos to cool and collapse, and has the potential to strongly influence gas dynamics and star formation within these halos (Tseliakhovich, Barkana, & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich, Barkana and Hirata2011; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012).

Early studies of this process, based on numerical simulations, indeed suggest that the kinetic energy provided by the streaming velocity provides additional stability. It reduces the baryon overdensity in low-mass halos and delays the onset of cooling, altogether resulting in a larger critical mass for collapse (Greif et al. Reference Greif, White, Klessen and Springel2011; Stacy, Bromm & Loeb Reference Stacy, Bromm and Loeb2011; Maio et al. Reference Maio, Khochfar, Johnson and Ciardi2011; Naoz, Yoshida, & Gnedin Reference Naoz, Yoshida and Gnedin2012, Reference Naoz, Yoshida and Gnedin2013; O’Leary & McQuinn Reference O’Leary and McQuinn2012; Latif, Niemeyer, & Schleicher Reference Latif, Niemeyer and Schleicher2014b; Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017) and different angular momentum evolution of dark matter and dense gas (Chiou et al. Reference Chiou, Naoz, Marinacci and Vogelsberger2018; Druschke et al. Reference Druschke, Schauer, Glover and Klessen2018). They may also have substantial impact on the resulting ![]() $21\,$cm emission (Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012; McQuinn Reference McQuinn2012; Visbal et al. Reference Visbal, Barkana, Fialkov, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012). Specific to the subject of this review, it has been suggested that the presence of large streaming velocities may create the ideal conditions for the formation of SMBHs by preventing fragmentation and the formation of normal Population III stars (Tanaka & Li Reference Tanaka and Li2014b). Indeed, Visbal et al. (Reference Visbal, Haiman and Bryan2014b) and Schauer et al. (Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017) indicate that streaming velocities may suppress the formation of

$21\,$cm emission (Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012; McQuinn Reference McQuinn2012; Visbal et al. Reference Visbal, Barkana, Fialkov, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012). Specific to the subject of this review, it has been suggested that the presence of large streaming velocities may create the ideal conditions for the formation of SMBHs by preventing fragmentation and the formation of normal Population III stars (Tanaka & Li Reference Tanaka and Li2014b). Indeed, Visbal et al. (Reference Visbal, Haiman and Bryan2014b) and Schauer et al. (Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017) indicate that streaming velocities may suppress the formation of ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$, reduce the amount of cooling, and allow halos to reach the mass limit for atomic cooling to set in. However, their results also demonstrate that once collapse has set in,

${\rm{H}}_{2}$, reduce the amount of cooling, and allow halos to reach the mass limit for atomic cooling to set in. However, their results also demonstrate that once collapse has set in, ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ will rapidly form in the centre of the halo and lead to fragmentation and the onset of a more normal mode of star formation. Therefore, we may conclude that external irradiation is still needed in the presence of streaming velocities to enable the formation of SMBHs by direct collapse. Indeed, Schauer et al. (Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017) argue that streaming velocities can facilitate the formation of synchronised halo pairs. In particular, if two halos form in close proximity to each other, then they can reach the atomic cooling phase at roughly the same time and start to go into collapse separated only by a few million years or less. The one forming stars earlier can then provide enough ultraviolet radiation to suppress

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ will rapidly form in the centre of the halo and lead to fragmentation and the onset of a more normal mode of star formation. Therefore, we may conclude that external irradiation is still needed in the presence of streaming velocities to enable the formation of SMBHs by direct collapse. Indeed, Schauer et al. (Reference Schauer, Regan, Glover and Klessen2017) argue that streaming velocities can facilitate the formation of synchronised halo pairs. In particular, if two halos form in close proximity to each other, then they can reach the atomic cooling phase at roughly the same time and start to go into collapse separated only by a few million years or less. The one forming stars earlier can then provide enough ultraviolet radiation to suppress ![]() ${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling in the other. If this second halo goes into collapse before the stars in the first halo explode as supernovae or before the metals from these explosions have reached it, (i.e., if strong cooling and fragmentation can be prevented), then this collapse may lead directly to the build-up of an SMBH (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Johnson, Khochfar, Pellegrini, Rydberg, Klessen and Oesch2017b, Reference Agarwal, Cullen, Khochfar, Ceverino and Klessen2018).

${\rm{H}}_{2}$ cooling in the other. If this second halo goes into collapse before the stars in the first halo explode as supernovae or before the metals from these explosions have reached it, (i.e., if strong cooling and fragmentation can be prevented), then this collapse may lead directly to the build-up of an SMBH (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Johnson, Khochfar, Pellegrini, Rydberg, Klessen and Oesch2017b, Reference Agarwal, Cullen, Khochfar, Ceverino and Klessen2018).

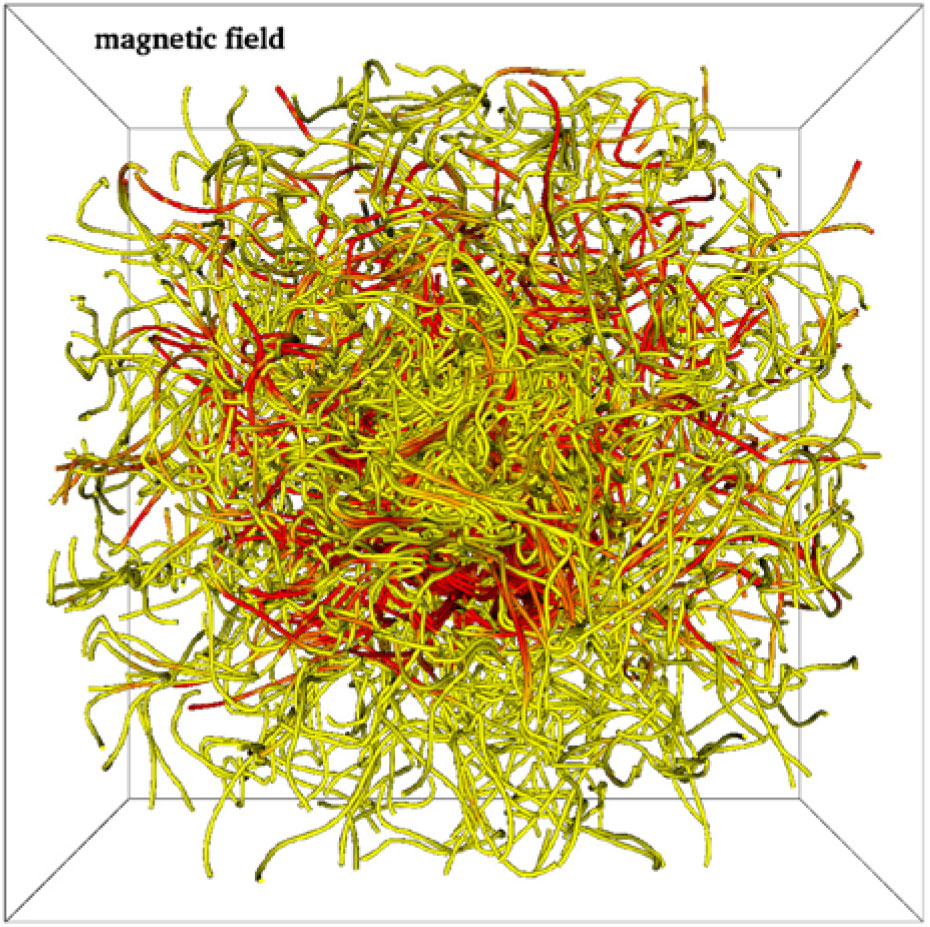

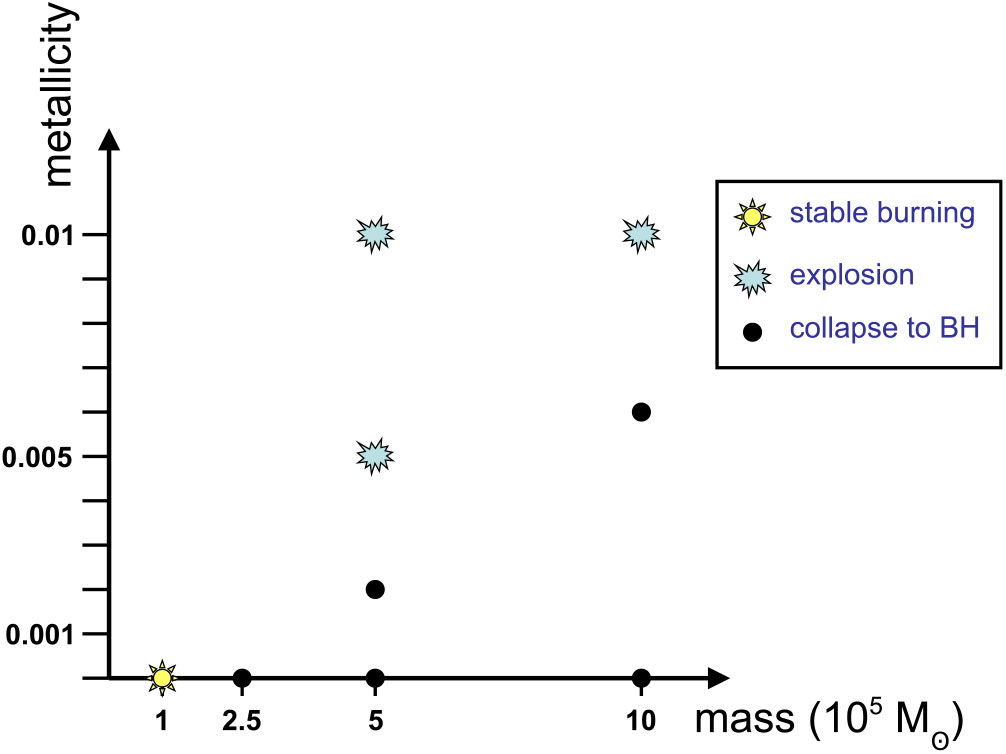

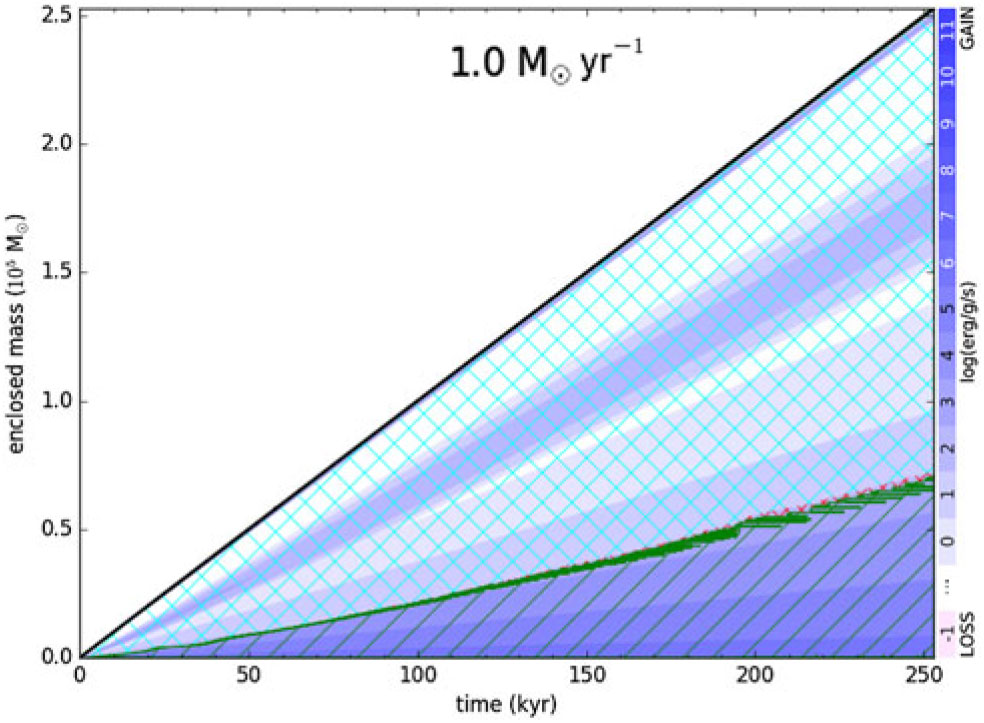

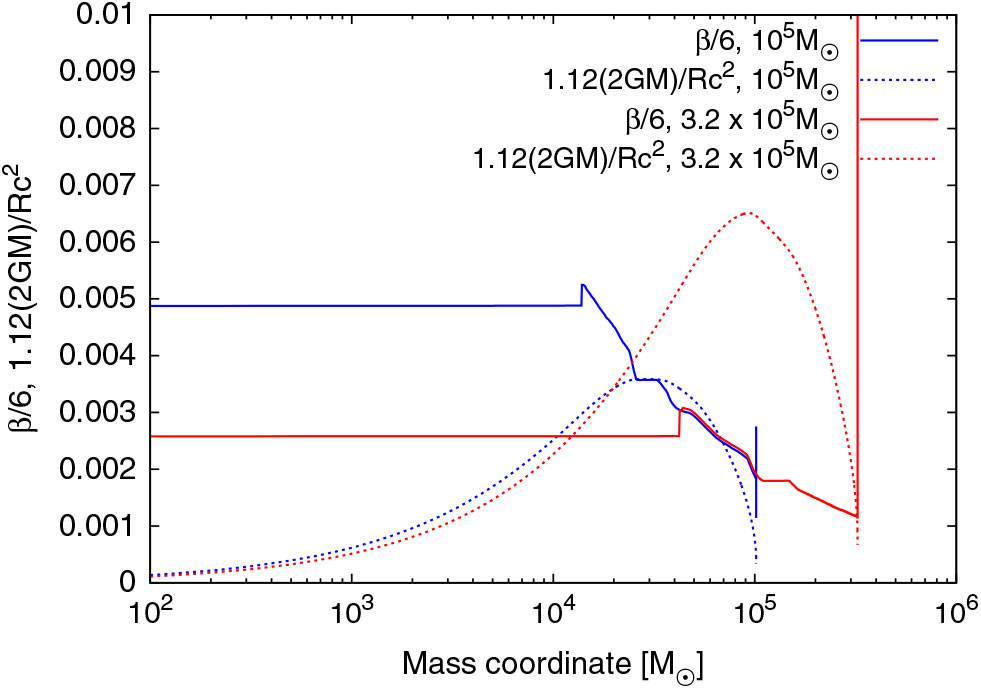

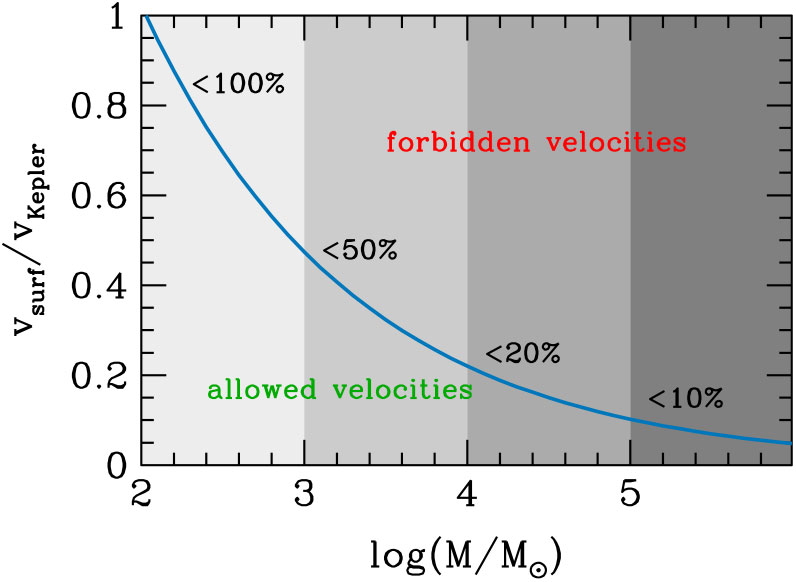

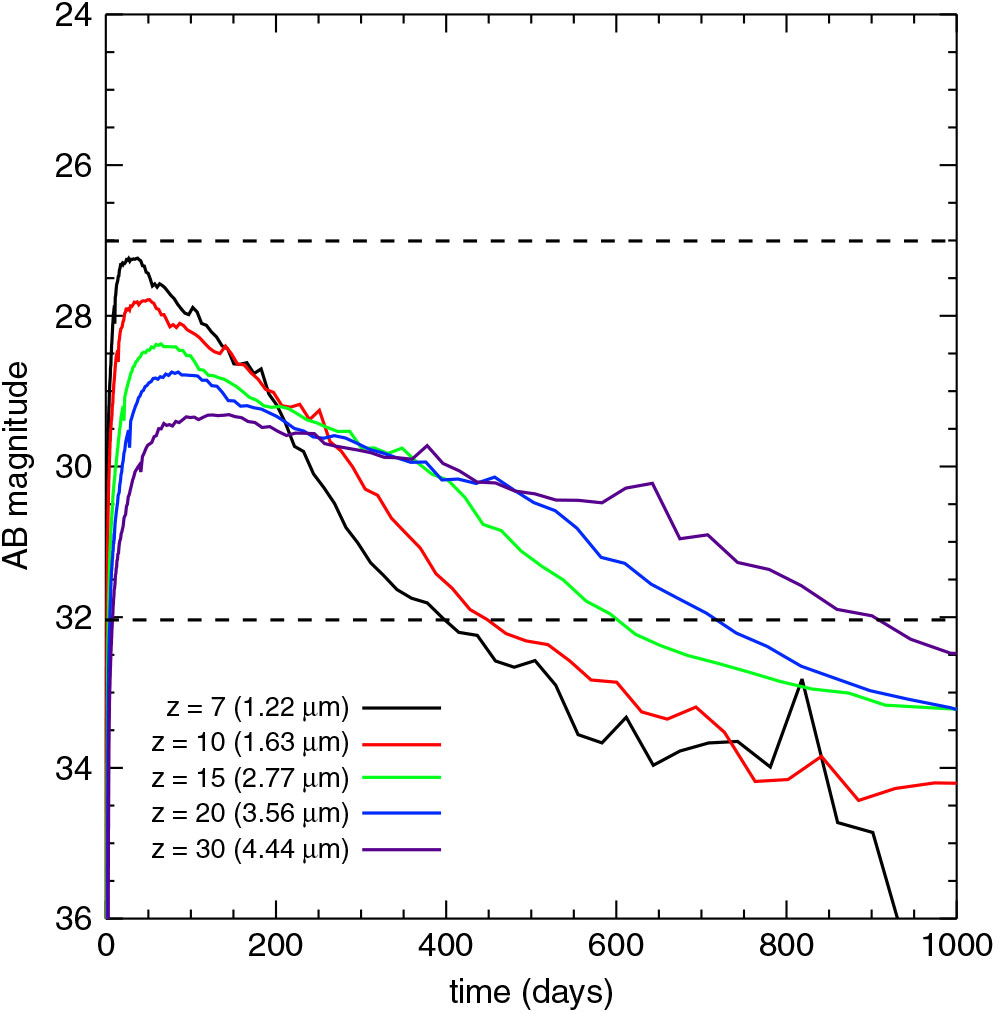

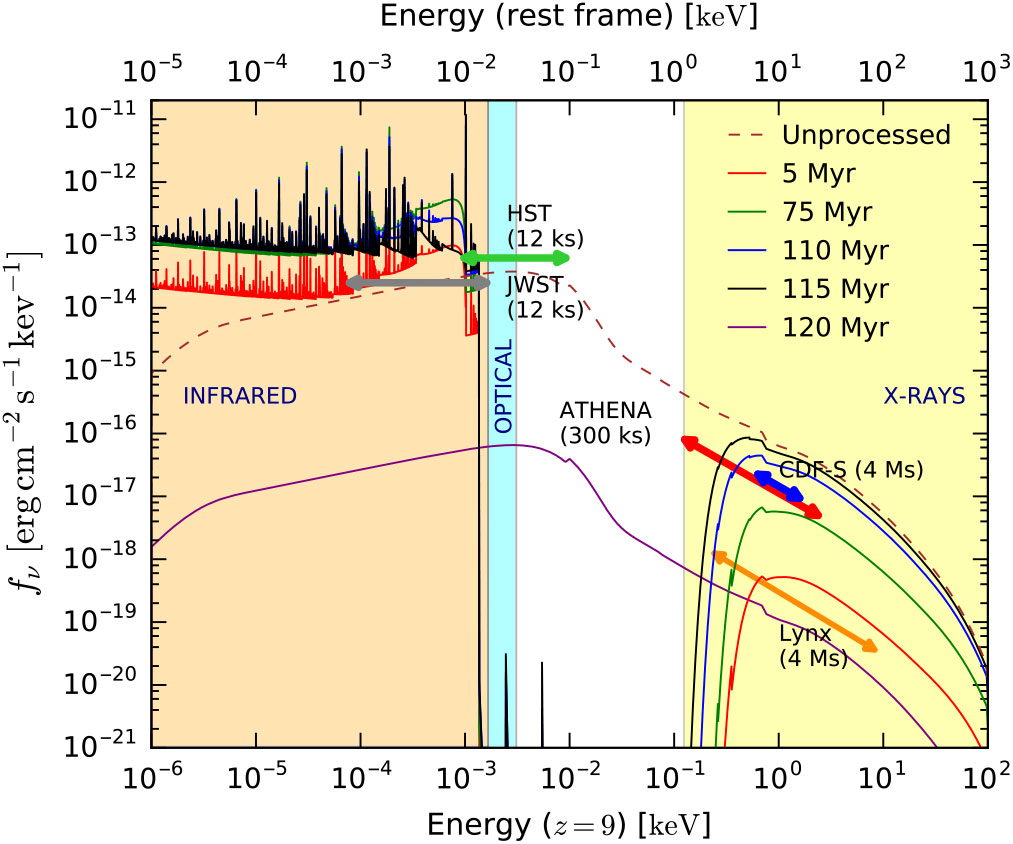

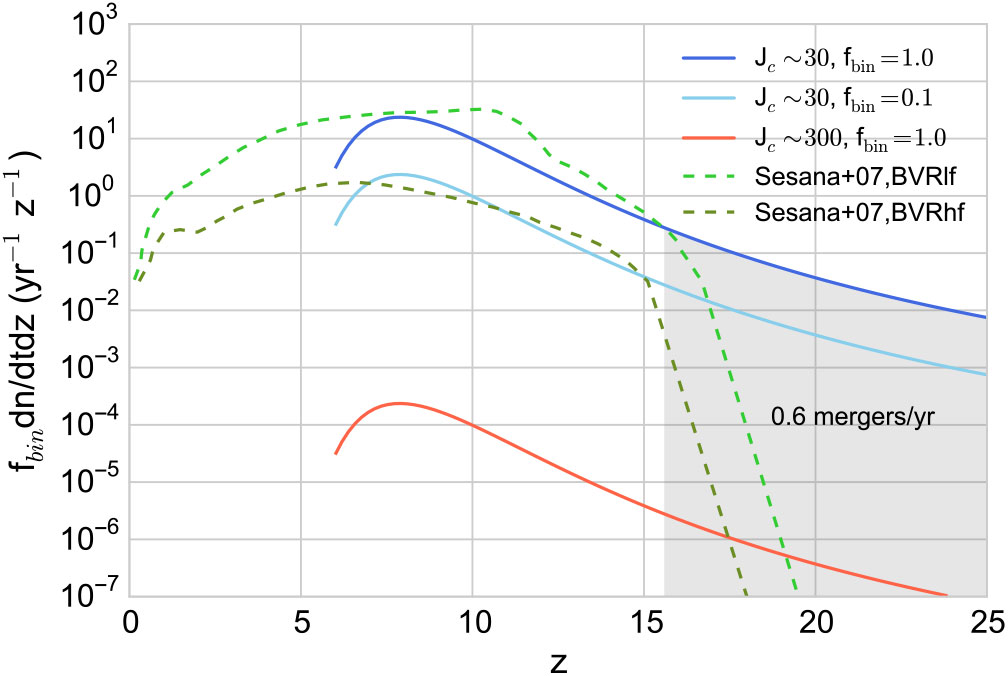

2.4. Magnetic fields