Students at Rhodes College have earned a national reputation for community engagement. For two years in a row, Newsweek magazine ranked the institution as the #1 Service-Oriented College in the United States. Washington Monthly identified Rhodes as the top college in the nation for the number of hours students committed to service (Rhodes College Reference Rhodes2019). Institutional support for experiential and community-engaged pedagogies inspired me to create these new opportunities for students interested in comparative and international politics. This article describes a community-engaged course titled “The Politics of Social Movements and Grassroots Organizing” that requires students to work at least 18 hours with local community partners involved in different types of service, advocacy, and activism. The course challenges students to think globally and act locally.

I argue that community-engaged pedagogies can significantly enhance comparative courses seeking to connect the local and the global. I suggest further that several elements contribute to the success of those courses. First, the instructor must be intentional about connecting activism observed on campus, in one’s city, in other US urban centers, and overseas. Second, to the extent possible, service-learning activities should be integrated into the course content. Instructors must dedicate class time to structured reflection and discussions of diversity, intercultural competence, and related issues. Third, exposing students to conceptual and theoretical frameworks allows them to ponder different modes of social action and deeper questions surrounding democratic citizenship.

The course focuses on urban movements both in the United States and abroad seeking to represent communities that have been politically marginalized on the basis of class, race, ethnicity, gender, and/or sexuality. Students examine how activists mobilize resources, build alliances, deploy discursive strategies, influence policy making, and shape the broader political culture. The most relevant social-movement theories and concepts include intersectionality, collective-action frames, political-opportunity structure, resource mobilization, and transnational advocacy networks. Students apply these theoretical and conceptual tools to case studies of activism in countries as varied as Bangladesh, Mexico, and Russia. They investigate volunteers who assist refugees in Germany and Sweden, protestors who demand their right to housing in Spain, child laborers who have unionized in Bolivia, and LGBTQ activists in Brazil and Argentina, among other sets of actors. In the US context, we discuss cases ranging from Black Lives Matter and environmental-justice movements in the Mississippi River’s “Chemical Corridor” to living-wage and migrants’-rights campaigns. We also take advantage of our location in Memphis by visiting the National Civil Rights Museum during the unit on non-violent resistance (syllabus details are in the appendix).

One of my primary responsibilities as a comparativist is to underscore how pressing challenges facing communities and college campuses all over the country—combating racial discrimination, sexual violence and misconduct, and economic injustice, for instance—are issues that mobilize activists around the globe on a daily basis. Many of our students’ concerns stem from a much larger set of problems that often are transnational in scope, as illustrated by the existence of global initiatives (e.g., V-Day, the movement to end all violence against women and girls). Borrowing from Enloe (Reference Enloe2011), I ask students to investigate how the personal is political and international.

One of my primary responsibilities as a comparativist is to underscore how pressing challenges facing communities and college campuses all over the country—combating racial discrimination, sexual violence and misconduct, and economic injustice, for instance—are issues that mobilize activists around the globe on a daily basis.

The course carries international studies and urban studies credit and fulfills a general requirement that students participate in activities that connect the classroom and the world. It has no prerequisites and is open to all. Enrollment is capped at 18 to keep the logistics manageable. Students are placed in organizations that serve and empower refugee families, migrants, Latinx communities, and people in situations of homelessness. They are required to submit a community-based–learning agreement, participate in any required orientations and training sessions, create a work schedule with their site supervisor, keep track of their hours, and write a community-based–learning log. In addition, students engage in extensive, structured reflections about experiences in their site placements to facilitate connections to our course materials and linkages between the local and the global. Specifically, they write papers on their goals and expectations for community-based learning, issues of importance to community partners, and activist and advocacy strategies (assignment guidelines are in the appendix). I adjust the course workload to accommodate time spent in the community: I do not administer the usual midterm and final examinations; nor do I assign a longer research paper.

It is vital to dedicate time in the first part of the course to prepare students for successful community engagement. We discuss diversity and intercultural competence, empathy, and humility. I caution against swooping into an organization with aspirations of “fixing” everything. We also read several chapters of Stoecker, Tryon, and Hilgendorf’s (Reference Stoecker, Tryon and Hilgendorf2009) The Unheard Voices: Community Organizations and Service Learning, which provides a wealth of insight into partnerships that are genuinely reciprocal and mutually beneficial. Later, I facilitate structured reflections during several class sessions in both small and large groups. These discussions allow students to share experiences at their work sites, challenges that have arisen (and how they overcame those obstacles), special opportunities, and benefits of working there. We ask whether their experiences connect with the overseas cases of activism that we examine and if they align with any of the social-movement theories, conceptual tools, and empirical findings discussed in class (discussion questions are in the appendix).

Engagement with community partners supports several learning objectives. Students apply social-movement theories to real-life situations and develop a better understanding of activists and the communities they seek to empower. Importantly, they gain intercultural competence through their work with diverse communities. Students increasingly view themselves as members of a larger community that exists both locally and globally (Colby et al. Reference Colby and Ehrlich2000). By “immersing themselves in a real-world environment,” students see the “complexity of situations faced by the people with whom they interact” and the relevance of broader issues “globally and locally, in theory and in practice” (Krain and Nurse Reference Krain and Nurse2004, 193). Additionally, service learning promotes an “understanding of the engaged role individuals must play if communities and democracies are to flourish” (Zlotkowski Reference Zlotkowski, McIlrath and MacLabhrainn2007, 43). Political scientists obviously have a stake in debates surrounding citizenship and civic engagement. It is surprising, however, that service-learning courses remain “outside of mainstream political science departmental offerings” (Dicklitch Reference Dicklitch, Rios, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2013, 247). In particular, community-engaged–learning experiences in comparative politics and international relations courses are not extensively documented.

Political scientists who have experimented with community-based learning bring different perspectives on engaged citizenship to their courses. Some implement service learning to underscore the importance of public service and enhance the welfare of the community. Patterson (Reference Patterson2000) required students of international relations to work with a refugee resettlement NGO and to package household items for donating to a refugee family. The project encourages students to “value and practice responsible global citizenship” through their interactions with the families (Patterson Reference Patterson2000, 817).

In contrast, Walker (Reference Walker2000) wondered if directly helping another person is the most effective way to make a difference in one’s community. Walker (2000, 647) challenged those who regard service as a “morally superior alternative” to other forms of political engagement. If students conceptualize civic engagement merely as an individual-level mode of action, “[t]hey are not necessarily challenging institutions in power. Feeding the hungry does nothing to disrupt or rethink poverty or injustice” (Walker Reference Walker2000, 647). Robinson (2000, 607) also lamented the relative absence of activities designed to address the structural roots of social problems and encourage political organizing more explicitly. Supporters of service learning harbor apolitical views: they prefer to “channel students into narrowly defined, direct-service, therapeutic activities” geared toward “needy populations”; service learning risks becoming “a glorified welfare system.”

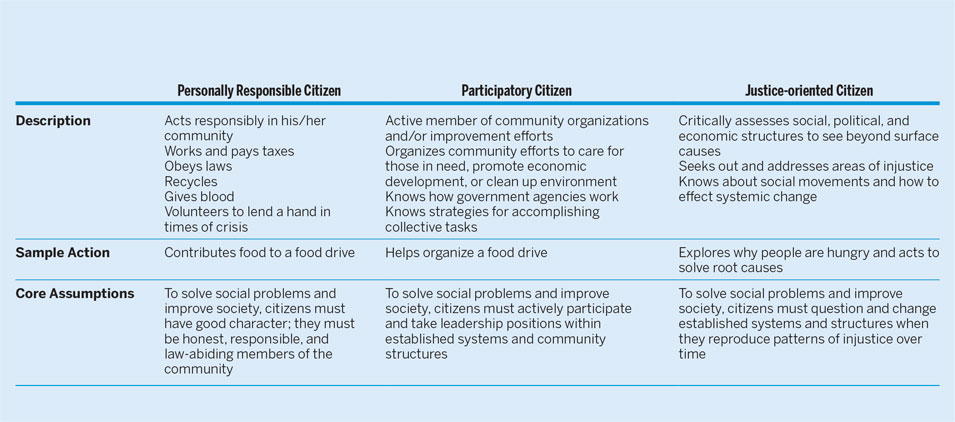

Before teaching the social-movements course, I was mindful of these critiques and concerned that many potential community organizations in my city were positioned on the “helping-the-needy” end of the spectrum. I ask students to engage with these debates at the beginning of the course, and we revisit them all semester. Early on, we draw from Westheimer and Kahne’s (Reference Westheimer and Kahne2004) framework, which contrasts personally responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented modes of citizenship. Table 1 summarizes their three proposed categories. Throughout the semester, students must grapple with these debates and the contending approaches toward social action found within their community sites and within themselves. Are they “helpers” lending a hand to someone “in need,” advocates for policy change, or “rebels” challenging systemic injustices (Training for Change 2018)? My job is to give students the conceptual tools they need to think through these issues and to encourage open dialogue without privileging a certain mode of action.

Early on, we draw from Westheimer and Kahne’s (Reference Westheimer and Kahne2004) framework, which contrasts personally responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented modes of citizenship.

Over time, many students perceive changes in themselves and/or within their community organizations. Individuals who at first identify with the personally-responsible-citizen description frequently move toward the justice-oriented perspective (and vice versa). Similarly, students who initially view themselves as “rebels” eventually may gain a greater appreciation for service providers and “helpers.” Meanwhile, students with an affinity for the “helper” role sometimes find themselves questioning the adequacy of such an approach by the end of the semester.

The course entails several forms of assessment. As the semester concludes, site supervisors evaluate each student’s progress toward the goals agreed on in the community-based–learning agreement and assess their overall work performance, professionalism, dependability, ability to complete projects, and ability to communicate and cooperate with team members. Students also have the opportunity to evaluate their community-based–learning experiences and the course. The feedback from the latest version of the course, taught in fall 2018, indicated that students are more willing to get involved in advocacy, activism, and/or service work in the future, as follows: 100% responded that they were more likely to get involved (71.4% indicated that they were “much more likely”); 92.9% described their progress toward gaining knowledge about different activist communities both within the United States and overseas as “substantial” or “exceptional”; 100% described their progress toward gaining knowledge about problems and issues that activists tackle in local, national, and/or overseas communities as “substantial” or “exceptional”; and 85.7% described their progress toward developing intercultural competence that allows for meaningful interaction with a diversity of people and communities as “substantial” or “exceptional.”

In short, students reported significant progress toward the course’s learning objectives. I would be remiss, however, if I failed to mention downsides of teaching or enrolling in the class. One challenge is the academic calendar that marks our time as professors and students. Semester-long experiences rarely coincide with the amount of time needed to complete meaningful projects within partner organizations. A few of my students—especially those who had worked closely with refugee families—indicated their interest in continuing at their sites. However, many had other plans, including studying abroad, doing service work elsewhere, graduating, and starting new jobs. By the end of the term, we all had a sinking feeling that we were somehow abandoning our posts and disappointing our partners. Moreover, existing scholarship frequently notes the extra resources and effort that community-engaged teaching entails. If one’s home campus lacks a teaching and learning (or community-engagement) center, the process can be even more burdensome. Faculty who integrate service learning and similar activities into their courses spend more than the typical amount of preparation time arranging, accommodating, coordinating, readjusting, and mentoring. Implementing these pedagogies requires a level of commitment that many instructors are not able or willing to give.

The obstacles are not insurmountable. Existing literature advises faculty to connect service learning to their scholarly agendas (Furco Reference Furco, McIlrath and MacLabhrainn2007). When I first offered the course in 2016, I had researched civil society and social movements for almost 20 years; however, during my 10 years as a professor, I had never offered an elective on those topics. Needless to say, I was motivated to do so. Additionally, as noted at the outset, the broader aims of the course align with my institution’s service-oriented culture. The college location in a major metropolitan area is obviously a key asset. I also benefited from the help and encouragement of numerous faculty, staff, and members of the Memphis community.

Most important, the students are definitely up to the task. They have embraced the challenge of combining experiential learning with comparative, theoretical, and intersectional modes of analysis. They work enthusiastically in their organizations. They make a difference in the lives of individuals and the broader community. Students gain an appreciation for (and a stronger understanding of) different modes of political action and contending models of citizenship. In the process, they become more aware of the many possibilities that exist for them to effect change at local, national, and global levels. Students also grapple with the “moral and civic dimensions” of social and political issues (Colby et al. Reference Colby and Ehrlich2000, xxvi). It is necessary for all participants in the course to put their knowledge and values into dialogue with each other. This dialogue is integral to a liberal arts education. As Cronon (1999, 3) observed, “[t]ruly educated people love learning, but they love wisdom more…. They understand that knowledge serves values, and they strive to put knowledge and values into constant dialogue with each other.”

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000544

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project would not have been possible without the Mellon Foundation’s support of faculty development at Rhodes College. Specifically, a grant titled “Supporting Academic Innovation in a Liberal Arts Setting” funded a Faculty Innovation Fellowship, which I received in 2014. I developed the course discussed in this article with considerable help from members of the Mellon Innovation Fellows Steering Committee; the faculty and staff involved in the community of practice; and two student fellows, Kirkwood Vangeli and Dominique DeFreece. I am grateful for the support and encouragement that Elizabeth Thomas, Shannon Hoffman, and Elizabeth Poston provided. Mostly, I am indebted to the students who enrolled in the course and the community partners who welcomed them into their organizations. Thanks also to organizers of the 2018 APSA Teaching and Learning Conference (February 2–4) in Baltimore, where I presented a longer version of this analysis.