Introduction

In the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, it is estimated that up to 2% of the population have psoriasis (Griffiths and Barker, Reference Griffiths and Barker2010), a visible and, for some, disabling, inflammatory skin disease (Bhosle et al., Reference Bhosle, Kulkarni, Feldman and Balkrishnan2006; Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Mork, Lillehol, Myrdal, Helland, Hanestad and Moum2006; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Papp, Wasel, Andrew, Fraquelli, Bernstein and Chan2010). Surveys of people coping with long-term conditions such as psoriasis can provide valuable insights and should lead to improvements in care. They also establish a baseline against which any future improvements in experience can be measured and evaluated. Although a large US survey of psoriasis patients is now some 14 years old, surveys have been conducted more recently in Canada, France and Europe (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Koo, Lebwohl, Menter, Stern and Rolstad2001; Fouere et al., Reference Fouere, Adjadj and Pawin2005; Schmitt-Egenolf, Reference Schmitt-Egenolf2006; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Paul, Feneron, Bardoulat, Thiriet, Camara and Ortonne2010; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Papp, Wasel, Andrew, Fraquelli, Bernstein and Chan2010), and a recent UK study focussed on the psychosocial impact of psoriasis (Anstey et al., Reference Anstey, McAteer, Kamath and Percival2012). These, and the more general psoriasis literature, document the difficulties experienced by those with this condition such as soreness, stigmatisation, difficult-to-manage treatment regimes, morbidity, associated co-morbidity, and a negative impact on their quality of life (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Koo, Lebwohl, Menter, Stern and Rolstad2001; Fouere et al., Reference Fouere, Adjadj and Pawin2005; Langley et al., Reference Langley, Krueger and Griffiths2005; Gottlieb and Dann, Reference Gottlieb and Dann2009; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Paul, Feneron, Bardoulat, Thiriet, Camara and Ortonne2010; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Papp, Wasel, Andrew, Fraquelli, Bernstein and Chan2010).

Interestingly, one of the European studies suggested that in the UK people with psoriasis (n=246) were far more likely to rate their condition as ‘mild’ and to have treatments prescribed by their general practitioner (GP) when compared with their European counterparts from Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands (Fouere et al., Reference Fouere, Adjadj and Pawin2005), suggesting that psoriasis is a condition that is often managed in primary care settings in the United Kingdom. The other, larger, European study did not include participants from the United Kingdom (Dubertret et al., Reference Dubertret, Mrowietz, Ranki, van de Kerkhof, Chimenti, Lotti and Schafer2006) and a direct comparison of self-assessment of individuals’ psoriasis with the recent UK survey is difficult due to different terminology being used in the two studies: for example ‘very active’ may not equate to ‘severe’ (Anstey et al., Reference Anstey, McAteer, Kamath and Percival2012).

Although the recent UK study addressed psychosocial factors associated with psoriasis in some depth, there is a lack of recent research into the healthcare experiences of UK patients. The following is a report on the findings from a postal, paper-based, survey, which sought to remedy this and to assess and understand people’s experiences of diagnosis of psoriasis, their subsequent healthcare and treatments in the United Kingdom and the impact on daily life. The discussion includes consideration of key areas for improvement in care.

Material and methods

Materials

A questionnaire was designed to gather demographic data and information on members’ experiences of diagnosis, quality of care, treatment and healthcare professionals. The design of the questionnaire was patient-association driven and focused on topics that arose regularly on the patient/members’ helpline. In addition, a coping and quality of life section was included, which drew on issues covered in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; Finlay and Khan, Reference Finlay and Khan1994). However, in this instance it was not, nor intended to be, a scale, but a series of discrete questions with a dichotomous response for the purpose of gathering data about the impact of psoriasis on specific aspects of daily life. Participants could respond to two open questions in the survey with comments, but the data were predominantly quantitative. Before circulation of the survey, minor amendments to the questionnaire were incorporated following invited patient feedback. The research met the requirements of the Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work Ethics Committee at the University of Hertfordshire.

Sample and procedure

Questionnaires, accompanied by an introductory letter and a reply-paid envelope, were sent out to all members of The Psoriasis Association (n=2830) and 1619 were returned, giving a response rate of 57%. Fifty-five of the returned questionnaires contained insufficient data to merit inclusion, making the final sample size n=1564. Completion and return of the survey form were deemed consent to participate in the study and all data were entered anonymously into SPSS.

Results

Both sexes were equally represented as 751 (48%) participants were male. Ages ranged from below 10 years to over 80 years old and were classified in age groups. Table 1 presents the distribution of the sample by group together with the mean length of time since participants’ diagnosis with psoriasis. The mode age range of respondents was 61–70, representing 29% of the sample and the percentage of returned survey forms by age group was representative of the membership of The Psoriasis Association.

Table 1 Sample size and mean number of years since diagnosis, by age group

The length of time that respondents had been affected by the condition ranged from one month to 89 years. Naturally their age group had a bearing on this and, while the overall mean length of coping with the condition was 32 years 11 months, analysis of this by age group indicates that the mean length of experience with psoriasis was approximately equal to half participants’ current lifespan.

Respondents experienced different types of psoriasis and sometimes more than one type. Plaque psoriasis was the most common with 1265 (81%) participants reporting it. Guttate psoriasis was reported by 211 (13.5%) respondents, while localised and generalised pustular psoriasis were the least frequently reported, with 89 (6%) and 46 (3%) cases, respectively.

In terms of location, the scalp was the most commonly affected body area with 1160 (74%) reporting it, followed by nails, 725 (46%), sensitive/flexural areas, 396 (25%), and the face, 375 (24%). In addition, 472 respondents reported having psoriatic arthritis, 337 of whom had received a formal diagnosis (representing 21% of whole sample). Co-morbidity with psoriasis was common, with just under 70% reporting other conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes and osteoporosis.

Diagnosis and referral

The majority (91%) of participants had approached their GP for diagnosis in the first instance, with 25% already believing they had psoriasis. The remainder sought the advice of a pharmacist (2%) or other health professional, including chiropodists and dermatologists. Psoriasis was correctly diagnosed initially for 1180 (75%) participants. However, 300 (19%) were given an incorrect initial diagnosis and responses on some survey forms suggested that reaching the correct diagnosis could be a lengthy process, exceeding a year in some instances.

In total, 1027 (68%) of respondents were referred by their GP for specialist care and assessment, primarily to consultant dermatologists. Although 70% of those referrals were made on the initiative of the GP, some 298 (30%) participants requested referral by their GP. Twenty-three participants (2%) were initially referred to hospital-based dermatology specialist nurses; none were referred to dermatology specialist nurses in GPs’ surgeries. Of those who attended secondary care, 27% went on, after specialist consultation, to be referred to the dermatology specialist nurse. Only 49% of those seen in secondary care were able to re-access the specialist dermatology department without re-referral from their GP if the condition flared. Of the total sample, 465 (30%) had been admitted at some point for in-patient treatment, and two-thirds of these had been treated on a specialist ward. Only 42 respondents (2.6%) reported having in-patient treatment in the previous 12 months.

Healthcare experiences

At the point of diagnosis, whether by a GP in primary care or a specialist in secondary care, patients expressed some dissatisfaction with the information they received. Fifty-four per cent were not given adequate information about psoriasis and 56% were not given sufficient information about the treatments available. Seventy-four per cent reported that they were not offered different treatment options and many (54%) did not feel included in the decision-making process about their treatment. Forty-seven per cent would have welcomed more time, support and the opportunity to ask questions, and only 10% of participants were given contact details of support organisations.

In terms of information and decisions about their prescribed treatment, 1137 (72.7%) of the respondents felt that they were given enough information about the treatments proposed for them in terms of application, how long it would take to work and potential side effects. Only 64% felt that they had been given sufficient time to consider the choice of treatment. Although these are both comparatively sizeable percentages, in a sample of this magnitude, it means that there is still a considerable number of participants who are less satisfied with the information received and the opportunity to make choices.

Relationships with healthcare professionals were, nonetheless, largely positive. Participants only evaluated those health professionals with whom they came into regular contact and the following percentages relate to the sample size, given in brackets, responding about a specific professional. Rating their relationships as either satisfactory or excellent with their GP (n=1473) were 91% of respondents; with their consultant dermatologist (n=787), 87%; dermatology specialist nurse (n=360) 94%; and with their pharmacist (n=772), 97%.

Treatments and outcomes

Table 2 presents details of treatments being used by survey participants at the time of the study. Some patients were using up to nine different treatments, and topical treatments represented by far the largest category.

Table 2 Treatments being used at the time of the survey

UVB=ultraviolet B; PUVA=psoralen ultraviolet-A; FAE=fumaric acid esters.

Participants were using up to nine treatments concurrently.

Respondents were asked about both the severity of their psoriasis and about their expectations of treatments. Mild psoriasis was reported by 506 (32%), while 722 (46%) respondents classified it as moderate, and 320 (21%) as severe. Table 3 gives mean ratings of how important participants perceive different outcomes of treatment. With a minimum of 1 (not important) and a maximum of 4 (very important), mean scores over 3 signify ‘very important’.

Table 3 Mean ratings of treatment outcomes (minimum score=1, maximum score=4)

Mean importance of treatment outcome scores were then assessed by severity group (mild, moderate, severe) and differences in mean were subject to analysis of variance. These were found to differ significantly with P<0.05, suggesting that those with more severely self-rated psoriasis rated the importance of treatment outcomes more highly. Post hoc (LSD) analysis confirmed this. However, no significant differences in means were found between the groups rating their psoriasis as ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ for three options – clearance of visible areas, reduced redness and improvements to general well-being – indicating, perhaps, aspects of the condition that should be targeted for treatment in order to benefit most psoriasis patients.

Psychosocial, practical and emotional impacts

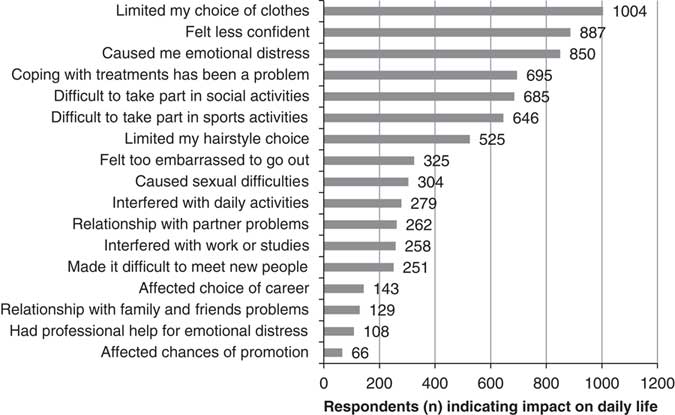

Respondents were asked to indicate how psoriasis had affected their daily life over the previous month and Figure 1 presents a frequency analysis of ‘yes’ responses.

Figure 1 The impact of psoriasis on daily living during the previous month

The main negative impacts of psoriasis were associated with coping with treatments, psychosocial functioning and emotional distress. However, the data also clearly indicated that despite 54% of respondents experiencing emotional distress, only 13% of those affected received professional help for it. Negative effects on work, study and promotion were considerably lower, but may be influenced by the age group of the sample as 53% of participants were over the age of 60. Indeed, age-related changes in the impact of psoriasis were found for other items (see Table 4) and suggest a lessening impact with age, particularly post-60 years.

Table 4 Effects of psoriasis on daily life (per cent)

ED=emotional distress.

Responses were given in relation to the previous month.

A comprehensive analysis of the rich qualitative data produced by the survey exceeds the scope of this article; however, reference to representative comments by respondents support the above findings. For example, topical treatments were perceived negatively by many patients. They were deemed sticky, messy, difficult and time-consuming, to the extent that they were viewed as ‘stressful’, ‘difficult to maintain’ and ‘a bigger nuisance than the condition’. Moreover, they were perceived by many to be ineffective. On the other hand, there were favourable reports by some for the biological therapies. Respondents indicated that GPs should be better informed, they wanted easier access to specialist dermatology clinics and greater innovation by the NHS with regard to psoriasis treatments.

Comments related to psychosocial factors affirmed the pervasive effects of psoriasis on individual lives. These ranged from the daily restrictions on clothing choices and no longer being able to swim or take part in sports, to the ‘embarrassment of itching and shedding scales at my desk’, and the severe negative impact on confidence, social lives, career choices and life paths. Many acknowledged that stress was a trigger for flare-ups, and this was often associated with the practical limitations imposed by psoriasis or arising from the emotional distress, which can accompany psoriasis at any age. As one young woman wrote:

I feel very isolated living with psoriasis… I feel like it is taking over my entire body day by day and has reduced my confidence to nil.

Another respondent reported that her young granddaughter told her:

I’m not really frightened of you Granny, but I don’t like seeing your hands or feet.

Men were equally affected by the condition and one explained that:

… psoriasis now covers 75% of my body. I no longer swim. I sunbathe when alone. I have amicably separated from my wife as I am very sensitive about my condition.

Such findings, both quantitative and qualitative, indicate distressing aspects of the condition that do not currently appear to be adequately addressed.

Discussion

This survey presents a comprehensive assessment of the health experiences of people with psoriasis in the United Kingdom. It also offers a further insight into the impact of psoriasis on everyday life. The high response rate in this postal survey is, perhaps, indicative of some of the frustration experienced by psoriasis patients in relation to treatments that are currently available, and of the profound negative psychosocial impact and emotional distress associated with this long-term condition. Self-selection bias is a limitation of the study as participants were both members of the Psoriasis Association and prepared to complete the questionnaire. However, a benefit of sampling through the Psoriasis Association is twofold: access to many who do not regularly attend primary or secondary care for their psoriasis, and information collected in an independent setting.

In many respects, the findings tend to support those of surveys from the international literature, including the older US study (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Koo, Lebwohl, Menter, Stern and Rolstad2001), particularly in relation to knowledge, psychosocial functioning, emotional distress and dissatisfaction with available treatments. However, in this survey, when compared with the UK cohort in the European study (Fouere et al., Reference Fouere, Adjadj and Pawin2005), fewer Britons were likely to report their condition as ‘mild’. This may be due, perhaps, to both the larger sample size in this study and to a far more equitable gender ratio (48% participants were male compared with only 36% in the UK cohort in the European study). Respondents in this study were far less likely to report a negative impact of psoriasis on work and career than those in the Anstey et al. (Reference Anstey, McAteer, Kamath and Percival2012) study and, again, context is an important consideration when comparing findings. The Anstey et al. study was an online survey, which had a sample with a much younger age bias – median age group 40–44 years compared with the median age group of 61–70 years in this postal survey. Indeed 7% respondents in this study were over the age of 80. As might be expected, this is likely to affect responses to questions about work in the previous month. However, such a comparison may also give some indication as to why some of the negative psychosocial impact of psoriasis appears to lessen with age (Unaeze et al., Reference Unaeze, Nijsten, Murphy, Ravichandran and Stern2006).

The research provided an informative insight into the health and healthcare experiences of people with psoriasis and indicated a number of areas that merit further research or improvement. For example, health policy in England and Wales favours the self-management of long-term conditions, regarding the patient as expert (Department of Health, 2011a; 2011b). However, for this to be successful, and for patients to be able to properly manage their condition, it is essential that they are fully informed and involved in making choices about their treatment. Yet, in common with other research findings (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Papp, Wasel, Andrew, Fraquelli, Bernstein and Chan2010), respondents were aware of being under-informed, particularly by their GPs who, as their title suggests, do not have specialist knowledge of the condition nor of all available treatments. Indeed the qualitative data suggested that Psoriasis Association events and newsletters provide much-needed information that is not available to them elsewhere, and yet newly diagnosed patients were rarely given details of this or other skin disorder support organisations. Moreover, the ability to re-access specialist dermatology services as necessary, as clearly recommended in a 2006 White Paper (Department of Health, 2006), was not apparent according to this research with only half of the respondents able to do this, thus restricting their access to current opinion and knowledge.

The findings suggest scope for improving the training of primary care health professionals, both GPs and nurses, and for increasing the number of dermatology specialist nurses in primary care settings such as GP surgeries. In particular, the latter could help to address needs identified here by providing appropriate care for those with straightforward, pre-diagnosed stable plaque psoriasis, promoting better patient knowledge and ensuring that support group details are provided to all patients diagnosed with psoriasis. In this way changes at primary care level could help to improve patient care, optimise self-management and facilitate access and re-access to secondary care for those with hard-to-manage psoriasis.

In addition, current treatments frequently failed to meet patient needs and expectations. Topical treatments were the most commonly prescribed and yet patients found them difficult, unpleasant and time-consuming to manage, and perceived them as ineffective. As the effectiveness of treatments can depend on adherence to correct usage (Ersser et al., Reference Ersser, Cowdell, Latter and Healy2010), the difficulties that patients experience with them can render them ineffective, whether or not they have the potential to be effective, and can hinder a successful outcome as far as self-management is concerned. Patients need treatment appropriate to the severity of the condition (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Papp, Wasel, Andrew, Fraquelli, Bernstein and Chan2010) and realistic treatment regimes from medications that, as indicated by the respondents in this survey, reduce the visible evidence of the condition and improve general well-being. Certainly treatments that effectively improve visible appearance would have a positive consequence for well-being by allowing those with psoriasis a wider choice of clothing, and enabling them to be more socially active, thus promoting greater confidence. In a similar vein this could also widen access to sporting activities, which is vital given the emerging evidence of a link between psoriasis and other co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease (Gottlieb and Dann, Reference Gottlieb and Dann2009).

The findings also highlight a fundamental aspect of psoriasis, which continues to be overlooked by healthcare professionals and which, again, would contribute to general well-being: the lack of support for psychosocial functioning and emotional distress. For example, the disparity between the high proportion of respondents experiencing psoriasis-related emotional distress (54%) and those receiving psychological support for it (only 13% of the 54%) clearly indicates a need that is currently not being met. Moreover, strong similarities in responses to those found in the Anstey et al. (Reference Anstey, McAteer, Kamath and Percival2012) study regarding emotional distress and confidence suggest that, unlike some of the psychosocial functioning aspects, the negative impact of psoriasis on mental health and emotional well-being does not lessen with time and age. Evidence indicates that psychosocial and emotional support can be empowering, and can improve the condition and maintain those improvements by helping people to cope with stress and the daily hurdles imposed by psoriasis (Seng and Nee, Reference Seng and Nee1997; Griffiths and Richards, Reference Griffiths and Richards2001; Fortune et al., Reference Fortune, Richards, Kirby, Bowcock, Main and Griffiths2002). Given that stress is a known trigger for flare-ups, such support could prove crucial in helping to break the vicious circle. However, it is also recognised that resistance by some patients to accepting ‘psychological’ help has been identified (Fortune et al., Reference Fortune, Richards, Kirby, Bowcock, Main and Griffiths2002) and ways to overcome this may need to be researched and developed.

Conclusions

There were some encouraging findings in the survey in that relationships with healthcare professionals were, for most respondents, very positive and, concurring with other research (eg, Unaeze et al., Reference Unaeze, Nijsten, Murphy, Ravichandran and Stern2006), there appears to be a lessening impact on psychosocial functioning with age, and over time. The introduction and effectiveness of biological treatments were seen as positive, although they only benefitted 11% of respondents. However, aside from these factors, the experiences of respondents in this survey echo many of those in the 1998 US survey (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Koo, Lebwohl, Menter, Stern and Rolstad2001), which suggests, disappointingly, that solutions to many of the problems associated with psoriasis have advanced little over the last 14 years, despite continued research.

The findings of this survey highlight that patients need to be better informed about the condition and treatments, both at diagnosis and over time, so that they are in a position to manage their condition effectively. As suggested, improvements in training and resources at primary care level could help to achieve this. Secondly, topical treatments need to be developed further to become both manageable and effective, and to reflect the patient priorities, identified in the survey, related to improving visible appearance and promoting well-being. Finally, reports of the negative impact of psoriasis on psychosocial functioning and, in particular, the extent of emotional distress that is currently experienced underscore the urgent need to remedy the lack of formal social and psychological support mechanisms for those with psoriasis. These are key issues, which, if addressed or further researched, could provide positive and tangible benefits for people coping with psoriasis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of The Psoriasis Association who participated in this research and Gladys Edwards, former CE of The Psoriasis Association, for her support and contribution at the beginning of the project. The authors are grateful to Schering-Plough for their educational grant, which enabled the research to be carried out.