Background

In high income countries, the life expectancy of persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is nearing parity with that of the general population, particularly among those with CD4 counts above 350 cells/mm3 at the time of diagnosis, or within six months of initiating antiretroviral therapy (Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration, 2008). Consequently, healthcare for persons with HIV in Canada has become increasingly complex, requiring the integration of HIV-related care and treatment of co-morbid illness related to aging in the context of continued disparity in access to care by marginalized communities (Larochelle et al., Reference Larochelle, Feldman and Levesque2014). Meeting the comprehensive needs of the diverse population living with HIV is challenging our traditional health-care system’s structure of silos of expertise (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Umanski, Blank, Grossberg and Selwyn2010).

HIV is increasingly managed like many other complex chronic conditions, with primary care clinicians providing important comprehensive care (Kendall and Guenter, Reference Kendall and Guenter2006; Chu and Selwyn, Reference Chu and Selwyn2011; Aberg et al., Reference Aberg, Gallant, Ghanem, Emmanuel, Zingman and Horberg2014; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Wong, Taljaard, Glazier, Hogg, Younger and Manuel2015). In addition to improving primary care-specific outcomes, having a primary care physician in addition to an infectious disease specialist delivering care to HIV-positive individuals has been shown to improve HIV-related outcomes when compared to care delivered by either specialty alone (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Neeman, Davis, Schulze, Libman, Markson, Aronson and Bell2012).

Measuring and reporting on system performance is a key step in driving the health system transformation needed for improved management of complex chronic conditions like HIV, which may require collaboration across multiple providers, and other stakeholders (Smith, Reference Smith2009; Aggarwal and Hutchison, Reference Aggarwal and Hutchison2012; Best et al., Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz2012). As care for people living with HIV shifts from a disease-specific focus to a long term, person-centred orientation, with growing evidence supporting the important role of the primary healthcare (PHC) system (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Austin, Brach and Wagner2009), this study sought to develop a performance measurement framework to guide the implementation and evaluation of community-based care to this population.

Reflecting lessons learned in performance measurement over the past decade, particularly for people with complex chronic conditions, we aimed to develop a framework that adopted a whole-person, integrated view of care. This framework was distinct from the large body of HIV care performance indicators and clinical guidelines as it sought specifically to create a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, performance evaluation framework incorporating key elements relevant to the stakeholders who will ultimately be responsible for improving care; clinicians, patients, advocates, and policy-makers.

Methods

We sought to build a comprehensive, but not exhaustive, performance measurement framework for the community-based care of people with HIV. We began with the Hogg et al. framework for evaluating the performance of primary care organizations (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Rowan, Russell, Geneau and Muldoon2008), which embraces Donabedian’s traditional evaluation approach of assessing structure, process, and outcomes (Donabedian, Reference Donabedian1988), but also recognizes the relevance of the health system and community context in measuring quality of care. As our focus was ultimately on supporting performance improvement, we adopted the lens of the health system as a complex adaptive system in which stakeholders can act independently with implications across the system and on other stakeholders (Plsek and Greenhalgh, Reference Plsek and Greenhalgh2001). Accordingly, we used a stakeholder engagement approach to explore which performance indicators were priorities for different stakeholders, and how stakeholders in their own arenas might use performance information to promote optimal care for people with HIV (Brinkerhoff and Crosby, Reference Brinkerhoff and Crosby2002). A flow chart depicting our study methods can be found in Appendix A. This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network and Bruyère Continuing Care research ethics boards.

Step 1: drafting of the initial framework

We conducted a scoping review of performance indicators for HIV care in the United States and Canada and identified a broad set of 505 distinct indicators (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Kendall, Hogel, McLaren and Liddy2015). These indicators were then matched to the performance domains of the Hogg et al. primary care performance framework. We further added categories for patient-reported outcomes and patient safety to the framework, selecting indicators from the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s ‘Measuring Patient Experiences in Primary Health Care Survey’ (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2013) to populate these important domains of performance (Ontario Primary Care Performance Measurement Steering Committee, 2013).

We drafted a preliminary community-based HIV care performance framework for use in our stakeholder interviews, including indicators from our scoping review if they recurred frequently across sources in the literature and/or they reflected a unique stakeholder perspective. The preliminary framework included 102 indicators and was reviewed independently by six team members and by a group of 23 HIV researchers.

Step 2: stakeholder interviews

We conducted interviews with stakeholders from different backgrounds (primary care providers, specialists, policy-makers, community advocates, and people living with HIV) in order to (a) review the preliminary draft framework; (b) obtain diverse perspectives on the most important indicators and performance domains to include; (c) explore how people would use a framework, or data arising from its use, to ensure that indicators aligned with potential end use. We employed purposive snowball sampling to elicit the active participation of key stakeholders. Team members and HIV experts who participated in the initial draft review generated a list of stakeholders from the five groups. Participants were selected to maximize variation in stakeholder type as well as geographic location. Candidates were contacted by email and invited to participate in semi-structured telephone or in-person interviews.

Project goals and feedback from the initial review of the draft framework by the team and HIV experts were used to develop stakeholder-specific interview guides. Interviewees reviewed the draft framework during the interview offering feedback and answering questions throughout. The interview guide was iteratively revised to explore emerging ideas. Interviews were recorded and transcribed.

A coding template for qualitative analysis was developed a priori based on the research objectives and literature review. Two reviewers read all transcripts and coded the first five, concurring on 88% of segments coded, to ensure agreement on interpretation of the codes and data. Subsequent transcripts were coded independently by one of the reviewers using NVivo 10 software (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2012). All coded segments were then reviewed using immersion/crystallization to identify recurring themes, disconfirming statements, significant statements related to research questions or emerging from data or patterns within or across stakeholder groups (Borkan, Reference Borkan1999). Three other team members also reviewed the segments containing disconfirming statements. We used a constant comparative approach, moving between the interview findings, expert opinion on the initial draft framework, and existing literature on specific indicators, including the Primary Care Guidelines for Management of Persons Infected with HIV (Aberg et al., Reference Aberg, Gallant, Ghanem, Emmanuel, Zingman and Horberg2014), released midway through the project. This process ensured that where interview data lacked consensus, final decisions were informed by expert opinion and the most recent guidelines and literature.

Results

The initial draft framework was reviewed during interviews with 24 individuals representing five stakeholder groups (Table 1). Overall impressions across each of the stakeholder groups indicated that the framework was comprehensive and covered the important domains.

‘A lot of things that I worried I wouldn’t find, I eventually did find through the framework’.

[P1]

Table 1 Province and stakeholder characteristics of the interview participants

BC=British Columbia; MB=Manitoba; ON=Ontario; NS=Nova Scotia; NL=Newfoundland; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus.

a Two interviewees represented multiple stakeholder viewpoints and were counted in two categories.

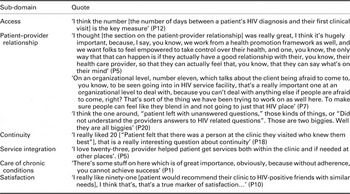

Stakeholders deemed all of the original domains to be appropriate. The majority of prompted and unprompted affirming statements related to sub-domains and indicators from the service delivery (Access, Patient–provider relationship, Continuity, Service integration) and patient-reported outcome (Satisfaction) domains (Table 2).

Table 2 Examples of quotes for domains and indicators receiving consensus support from interviewees

HIV=human immunodeficiency virus.

Suggested framework modifications

Context

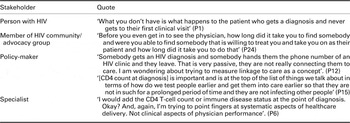

Health system and public health goals repeatedly emerged as inadequately addressed elements, particularly from policy-makers (Table 3). Measures suggested to help understand the health system context included the postal code and education level of patients receiving care (as proxy measures of the socioeconomic status of a patient population being served), the patient’s CD4 count at entry to care, time from diagnosis of HIV to being linked with HIV care, and volume of patients with HIV seen by a physician as an indicator of HIV expertise.

Table 3 Quotes identifying indicators of health system context as missing elements in the framework

HIV=human immunodeficiency virus.

Social determinants of health

Participants across stakeholder groups identified the importance of understanding the patient’s social context, specifically access to food, transportation, housing, and safety as an important element of high quality care not addressed in the framework. These elements were viewed as outside of the direct influence of the healthcare provider and themselves not markers of high quality care. However, the majority of stakeholders recognized that knowing the status of a patient’s social determinants of health was essential to optimize care. Of the 17 interviewees specifically asked, 15 (88%) agreed that indicators of screening for social determinants of health, and providing appropriate referrals to necessary support services where available, should be part of a performance framework.

‘A lot of the issues around access to care and clients being connected and staying in are completely influenced by the social indicators. So if you weren’t kind of monitoring what’s happening in their lives, it’s gonna be hard for you to understand how they’re managing clinically or taking their meds or anything else’.

[P7]

Care of acute conditions

Many of the healthcare professionals interviewed criticized the indicators related to care of acute conditions stating the standard of care had changed significantly since they were published in 2004 (Asch et al., Reference Asch, Fremont, Turner, Gifford, McCutchan, Mathews, Bozzette and Shapiro2004). The management of acute symptoms such as complicated cough or significant weight loss, was repeatedly described as patient- and context-dependent.

‘If someone has untreated or advanced HIV infection, the approach is much different than someone who’s watched while being treated for HIV’

[P11]

Controversial indicators

Three indicators within the framework generated diverse opinions despite agreement that the performance domains they aimed to measure were important:

Provider’s technical competency

Many people interviewed across stakeholder groups questioned the validity of a performance indicator measuring the patient’s assessment of their provider’s technical competency. Most interviewees felt technical competency would be better measured through many of the other indicators in the framework.

Availability of after-hours care

The indicator regarding availability of after-hours care elicited a large amount of feedback across stakeholders (Table 4). Interviewees recognized the importance of after-hours access to care almost universally. Debate arose, however, as some interviewees wondered whether the resources exist to offer this level care. There was consensus that access to primary care outside of regular working hours should be the optimal standard of care, despite not currently being available for many people with HIV.

Table 4 Conflicting opinions toward after-hours care: a comprehensive display of the interview data in favour of and against including an indicator regarding access to care outside of regular working hours

HIV=human immunodeficiency virus.

Frequency of screening

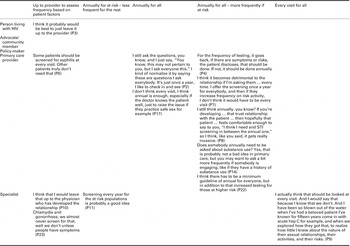

Certain indicators related to routine screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and infections associated with injection drug use, and discussions relating to substance use and safe sexual practices, were most commonly assessed for each visit in all the documents reviewed in our scoping review. However, our interviewees shared diverse perspectives, both within and across stakeholder groups, relating to how often they felt routine screening for risk behaviours and STIs should take place (Table 5). Responses ranged from those that felt screening should occur at every visit to those that felt it should be based completely on the provider’s assessment of the patient’s likelihood for STIs or behavioural risks. However, the majority of respondents across stakeholder groups agreed that such screening should be performed annually for all patients with HIV and more frequently if the provider deemed higher risks.

Table 5 Conflicting opinions toward frequency of routing screens: a comprehensive display of interview data relating to the frequency with which routine screening for and discussions about STIs, substance use, alcohol use, and high risk sexual activity should be performed

HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; STI=sexually transmitted infection.

Finally, a few indicators throughout the framework were critiqued by individual participants, often reflecting areas of emerging practice patterns such as providing anal pap exams.

The use of a performance framework and performance data for improving care for people with HIV

Most participants did not currently use performance data and suggested physicians caring for people with HIV might be most likely to use data from a framework like this to identify areas to improve.

‘It’s definitely a framework for, you know, how are we [primary care providers] providing good access, good therapeutic relationships, patient satisfaction. To have a standard way to assess those things would be great’.

[P7]

However, most providers did not envision using such a performance framework or performance data from it as part of quality improvement efforts. Providers most often cited a lack of resources as the primary barrier to routine performance measurement and the use of such a framework in their practices.

‘I think resources are going to be an issue, to actually sit down and ask us to do our own chart reviews or to be administering these questionnaires to patients and so forth, I am not sure it is going to get done’

[P21]

Of the individuals currently collecting and/or using performance data, the majority obtained their data from electronic medical records for quality improvement purposes. Most suggested a provider or practice would pick only a few priority indicators on which to obtain data for quality improvement but might be informed by such a framework.

A few participants, including both providers and patients, noted that such a comprehensive framework could be used as a checklist for both patients and providers.

‘I wonder if it might not be helpful to have this in a form of a checklist. And something that most patients and doctors could review. And you know, from a patient’s perspective, to be able to check off, you know, how they feel about their quality of care that they’re receiving, and you know, for doctors to be able to look and you know, see what level of care they are providing’.

[P3]

Final framework

Indicators for the screening for social determinants of health as well as appropriate referrals to social services were included in the revised framework. The indicator of a patient-assessed physician’s technical competencies was removed. The ‘Care of Acute Conditions’ section was removed. Indicators reflecting current standards of optimal medication management for people living with HIV derived from feedback from team members and triangulation with most recent care guidelines were added.

The section on screening manoeuvres for patients newly diagnosed with HIV or entering into the health-care system was significantly expanded primarily based on triangulation with the Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines (from 11 to 30 indicators covering disease status at entry to care, lifestyle behaviours, STI and Hepatitis screening, vaccinations, medication history, mental health screening, and evaluation of the patient’s social determinants of health) (Aberg et al., Reference Aberg, Gallant, Ghanem, Emmanuel, Zingman and Horberg2014).

The final version of the framework contains 79 indicators (Appendix B).

Discussion

The goal of this work was to develop a performance measurement framework for evaluating the quality of primary care provided to people with HIV. Our final framework contains a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, set of indicators addressing priorities to key stakeholders in improving HIV care; providers, patients, advocates, and policy-makers. It is distinct from the major clinical primary care guidelines for people living with HIV as it covers more than just the clinical delivery of care, incorporating health system indicators and patient-reported indicators.

The comprehensive nature of the performance framework was strongly endorsed by all stakeholders, reflecting a shared recognition of the importance of whole-person care for people with HIV (Chu and Selwyn, Reference Chu and Selwyn2011). Performance domains most poorly represented in the HIV care indicator literature, such as continuity of care, service integration, and patient-reported outcomes (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Kendall, Hogel, McLaren and Liddy2015), were identified as important components of the final framework. The concept of whole-person care was further expanded to include comprehensive screening for social determinants of health reflecting both the complexity of needs and co-morbidities of some people with HIV, and the importance of understanding a patient’s whole context and risk profile in order to provide optimal care. This was also evident in the approach to screening for risk behaviour and STIs forging a middle ground between at every visit and at a provider’s discretion, with an annual screen and expectation of more frequent testing or behaviour screening if an individual was at higher risk. The Public Health Agency of Canada recommends that providers discuss sexual activity and drug use at every visit with people living with HIV (Expert Working Group for the Canadian Guideliens on Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2006). Understanding a person’s risk would require an ongoing assessment of more than just their disease burden. However, the results seemed to suggest that a discussion at every visit about risk factors might not be optimal whole-person care for some patients.

The framework recognizes the need to potentially manage multiple co-morbidities alongside HIV, from cardiovascular risk factors to mood disorders to domestic violence. Nonetheless, many of the indicators reflect optimal practice for caring for a person with a single condition. In the absence of indicators designed for people with multiple co-morbidities, using richer data including the presence of socioeconomic risk factors for suboptimal health, processes to screen for and link with community-based services, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) might also help in understanding differences in outcomes in other data such as medication adherence or CD4 counts across the highly variable population with HIV (McGlynn et al., Reference McGlynn, Schneider and Kerr2014).

This framework highlights that an integrated approach to measuring performance and assessment across traditional silos of care from public health to PHC and specialty care is required (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Rowan, Russell, Geneau and Muldoon2008). Many indicators reflect a shared accountability across heath system sectors both horizontally, where specialists and primary care may contribute to optimal symptom and disease management, and vertically as when community services and primary care both support a patient’s health as well as a community’s health. The included indicators were prioritized by our sample which, while not representative of all stakeholders in HIV care, included participants with significant experience caring for people with HIV and/or responsibility for the system providing care across diverse roles of primary care providers, specialists, policy-makers, and community advocates. Data on how well those priorities are achieved may spur the development of common agendas across independent stakeholders enabling them to identify and build solutions together. This was identified even at the practice level by suggestions from a few participants that the framework could be used as a comprehensive guide or checklist for patients and providers to share together. Further, the inclusion of performance indicators reflecting an optimal standard of care, despite the health system lacking resources to offer that level of care to many people, may nonetheless serve to identify these important areas of inequity which may require system-wide solutions.

A ‘shared accountability model’ for performance measurement (Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Goodrich and Conway2014) may be difficult to implement. The role of performance measurement and reporting in driving improvement in care of people with HIV was not easily identified across stakeholders. The limited suggestions focused on physicians’ usage of a few selected indicators from this framework to drive practice level quality improvement. However, a system relying primarily on individual provider- or practice-driven change will have little use for data focused on integrated care, community context or system resources which may require multiple stakeholders working together across their silos to foster improved outcomes. It will certainly not support the kind of practice level commitment to data collection and data aggregation needed to create an integrated view of the health system’s performance (McGlynn et al., Reference McGlynn, Schneider and Kerr2014) in caring for people with complex chronic conditions like HIV.

Developing system-level performance measurement often requires government leadership and is unlikely to emerge from provider-led quality improvement efforts (Smith, Reference Smith2009). Important advances are being made in provinces like Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia in creating administrative data sets to evaluate population-level outcomes for people with HIV (Lima et al., Reference Lima, Le, Nosyk, Barrios, Yip, Hogg, Harrigan and Montaner2012; Antoniou et al., Reference Antoniou, Zagorski, Bayoumi, Loutfy, Strike, Raboud and Glazier2013; Heath et al., Reference Heath, Samji, Nosyk, Colley, Gilbert, Hogg and Montaner2014). However, quantitative assessments of the long-term care of people with HIV must incorporate indicators of complex and rapidly evolving HIV-specific care, as well as measures of access to care, coordination and integration with community services, patient-reported outcomes, and indicators of chronic condition management (Chu and Selwyn, Reference Chu and Selwyn2011).

The use of PROMs has been slowly growing in healthcare (Van Der Wees et al., Reference Van Der Wees, Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden, Ayanian, Black, Westert and Schneider2014) and the clear importance of the Framework’s PROMs to participants suggests that patients must play a greater role in collecting performance data (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2009). However, our current efforts at performance measurement, are often limited to select clinic-level, electronic medical record-derived indicators, or population-level metrics obtained from administrative or routinely collected data. The review of indicators of high quality HIV care conducted as background for this study found the New York Department of Health AIDS Institute, through its Patient Satisfaction Survey published in 2002 (New York Department of Health AIDS Institute, 2002), was the only major source of performance indicators with specific PROMs included out of 19 distinct resources, which generated their own HIV care performance indicators (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Kendall, Hogel, McLaren and Liddy2015). Further, the most common approaches used for patient survey have important limitations, especially for our most vulnerable populations. If performance indicators using PROMs are to be used to help guide reform of care for people with HIV or many other complex chronic conditions, we need novel, cost-effective and practical methods to collect and link these data to other data sources. For performance measurement to support improvements in care provided to people living with HIV, more than a set of indicators reflecting shared priorities is required. The infrastructure and culture around performance measurement in healthcare will also need to move forward.

Limitations

This study extracted previously published indicators of care for people with HIV, however, a number of indicators were adapted based on study results and require further validation. In addition, the controversy over emerging practices such as providing anal pap tests and the out-dated indicators for acute conditions reflect the rapidly changing standards for HIV care and highlights the need for a performance framework to be regularly revisited and updated as standards of care change. Our sample of 24 participants was selected to enable us to explore indicators and their potential use in depth while hearing and comparing diverse perspectives. While there was significant consensus across stakeholders on most indicators, it is possible that some groups not interviewed, such as those from significantly marginalized populations, might have expressed different views. As our initial focus was on developing a framework including PHC as the foundation, we did not include performance indicators for home-based care or community-based social services, which also contribute to the optimal care for people with HIV.

Conclusions

The performance framework for community-based PHC for people with HIV presents a comprehensive though not exhaustive tool to support performance measurement and improvement in the care for people with HIV. The diversity of indicators that received pan-stakeholder support highlight the changing model of care for people with HIV towards that of a complex chronic condition, managed across the life span, requiring integrated care across traditional health system divisions. There is a role for patient-reported outcomes in assessing the quality of care that will challenge our capacity to involve patients in health system performance assessment. However, using a performance framework to guide efforts to improve care across the performance domains prioritized by diverse stakeholder groups may still require significant improvements in data collection infrastructure and performance management culture in healthcare.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

The authors would like to acknowledge the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) for providing the funding that supported this research project (Grant #TT5-128270), as well as in supporting A.B. through a New Investigator award.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Appendix A

Appendix B