“Gender blindness” refers to an unawareness of or a failure to account for the significance of gender socialization, roles, needs, opportunities, and interactions, based on the assumption that men and women react the same way or are similarly affected by a given phenomenon (Bacchi Reference Bacchi, Essed, Goldberg and Kobayashi2009; Pedrero Reference Pedrero1999). In recent decades, this topic has increasingly attracted the attention of scholars and researchers, even in fields that do not engage with gender as a matter of course (such as medicine, engineering, and computer sciences). In these fields, the emerging awareness of gender blindness has led to the adoption of norms of gender-sensitive analysis reflected in research questions as well as research designs (Schiebinger and Schraudner Reference Schiebinger and Schraudner2011).

In mainstream political science, however, gender scholars have lamented the lack of sufficient consideration of gender (Tripp Reference Tripp2006). They claim that despite a rich feminist political theory and gender-focused subfield, gender-sensitive analysis has been slow to enter the mainstream political science corpus (Caraway Reference Caraway2010; Krook Reference Krook2011; Medeiros, Forest, and Öhberg Reference Medeiros, Forest and Öhberg2020). This slow uptake could be consequential, as gender-sensitive analysis can greatly enhance the usefulness and precision of research findings, and it can contribute to improving and refining theories (Agarwal, Humphries, and Robeyns Reference Agarwal, Humphries and Robeyns2003). It could also increase the usefulness of academic research for policy makers looking for viable, effective, and sustainable policy solutions (True Reference True2003).

Motivated by the conclusions of many before us who have criticized the disregard of gender within political science (e.g., Krook Reference Krook2011; Medeiros, Forest, and Öhberg Reference Medeiros, Forest and Öhberg2020), we attempt to demonstrate the risk of gender blindness and to evaluate its prevalence in political science research. That said, we are by no means arguing that taking gender into account is required in all research designs. The absence or inclusion of gender as an important category—like other categories such as race, ethnicity, or age—depends first and foremost on the distinctive theoretical question and the unique aims and arguments of the specific research.

Gender blindness takes different forms in different types of research (i.e., theoretical, empirical, quantitative, qualitative, individually oriented, structurally oriented, etc.), and each type requires unique guidelines to identify and address gender blindness. In this study, we limit our focus to empirical quantitative analysis as a starting point for incorporating gender-sensitive analysis into political science research. An examination of this type of research is significant, as quantitative methods have become increasingly predominant in the field of political science (Groeneveld, et al. Reference Groeneveld, Tummers, Bronkhorst, Ashikali and van Thiel2015; Merritt Reference Merritt1985). Indeed, in the leading journal examined in this study, the vast majority of articles were empirical and used quantitative methodology.

We begin by discussing the relevance of assessing gender blindness, specifically within the field of political science, and the challenge that this topic poses to quantitative analysis. We then propose a set of questions to help identify and recognize gender blindness in political science quantitative research, based on criteria developed in other fields. Following that, we progress in two stages to answer questions about the implications and prevalence of gender blindness. First, we explore the impact of gender blindness on research outcomes by applying gender-sensitive analysis to three articles that use quantitative research methods that were published in the American Journal of Political Science (AJPS), one of the field’s top journals. Two of these cases demonstrate how research outcomes and conclusions can change when we account for gender. After presenting these illustrative cases, we review all articles (N = 114) published in the same journal over a two-year period. Using guidelines for gender-sensitive analysis from other fields, we map all the quantitative articles according to the extent to which their research is subject to gender blindness in order to estimate its prevalence in quantitative political science research.

Gender Blindness and the Field of Political Science

There is a rich subfield of feminist theory and gender studies in political science, but the field as a whole has yet to introduce widespread considerations of gender blindness. Although multiple journals are dedicated to the subfield, and articles on politics and gender can be found in the highest-ranking mainstream political science journals, the question remains whether political science, beyond the gender and politics subfield, acknowledges the benefit that gender-sensitive analysis has to offer (Krook Reference Krook2011; Tripp Reference Tripp2006). While some subfields, such as comparative politics (Caraway Reference Caraway2010; Krook Reference Krook2011; Tripp Reference Tripp2006) and international relations (Blanchard Reference Blanchard2003; Tickner Reference Tickner1992), have already begun to explore the issue, others have yet to join the discussion (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2021).

Caraway (Reference Caraway2010) proposes a number of reasons why gender is often overlooked in political science. First, gender is categorized as its own subfield. It is seen as a freestanding area of study rather than one that overlaps with other subfields. Second, political scientists often see gender questions as belonging to the fields of sociology and gender studies and therefore irrelevant for mainstream political science outlets. Finally, as gender studies and female researchers have historically been on the margins of the academic community—including within political science—they continue to be excluded from core syllabi and teachings presenting canonical work. Thus, in our classrooms, we continue to produce political scientists who see gender as a niche rather than a mainstream consideration.

Tickner (Reference Tickner2005) points out that the recent emphasis on quantitative analysis in political science might itself give rise to certain gender biases in the analysis of political phenomena. According to Tickner, norms of operationalization can introduce gender biases and veil differences in men and women’s experiences. An example of this argument can be seen in Sainsbury’s (Reference Sainsbury, Goertz and Mazur2008) critique of Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) welfare state typology. Sainsbury argues that classic conceptions of the welfare state are biased because they rely solely on the historically predominantly male experience in the labor market while ignoring women’s contributions as welfare suppliers. Based on this criticism, she challenges the basic analytical concepts upon which the typology is established and questions its validity.

In the case of political phenomena—such as the activity of state institutions, organizational structure, political representatives, citizens, and policy outcomes—acknowledging the importance of gender can improve the explanatory power of theories and typologies (Agarwal, Humphries, and Robeyns Reference Agarwal, Humphries and Robeyns2003). For example, Acker (Reference Acker1990, Reference Acker2006) addresses the gendered nature of organizational structures, arguing that organizations are a key site in which gender norms are formed and reproduced. Although organizational structures are typically viewed as gender-neutral, they are in fact built upon gender norms and assumptions. While these gendered assumptions are frequently unrecognized, they nevertheless set the criteria for wage hierarchies by directing men and women into different jobs and positions.

Another example of the power of gender-sensitive analysis comes from the study of federalism. According to Vickers (Reference Vickers2012), applying a gender perspective to the field of federalism introduces new concepts, questions, hypotheses, and debates. She points out that as the study of federalism often looks at the balance of power between different levels of government, an understanding of gender balances of power in society can explain cultural aspects that shape the balance of power in state institutions. She proposes a reconsideration of different forms of federalism to understand their impact on women’s marginalization and empowerment.

When practical implications are being considered, gender-sensitive analysis improves the policy-making process and leads to more successful policy. In cases in which the different experiences of men and women are evident, gender-sensitive analysis not only helps avoid flawed solutions (Llácer et al. Reference Llácer, Zunzunegui, del Amo, Mazarrasa and Bolůmar2007; Palmer Reference Palmer1995; Schiebinger and Schraudner Reference Schiebinger and Schraudner2011), but also leads researchers to solutions that are more efficient, socially acceptable, and viable (Green and Baden Reference Green and Baden1995; Leduc Reference Leduc2009). Grossmann (Reference Grossmann2021) contends that an awareness of biases related to different identities, including gender, is one of the keys to creating more reliable and usable research in the social sciences. He adds that the very identity of the researcher can be central to defining the research question and goals. The increasing effort to promote the representation of women and minorities in academia (European Commission 2009) is therefore a means of ensuring more gender-sensitive research. Gender-sensitive analysis has been endorsed, promoted, and developed by governments and intergovernmental organizations including the United Nations and the European Union (True Reference True2003).

While combating gender blindness does offer advantages, and a call has gone out for the acceptance of gender in mainstream political science research, no study to date has attempted to analyze mainstream political science research to consider the potential magnitude of the impact of gender blindness or its prevalence. This article, then, is a discrete attempt to test and catalog the scope of this phenomenon in one well-defined context: quantitative studies published in a leading general political science journal.

The Challenge that Multiple Identities Pose to Quantitative Analysis

With regard to accounting for identity in general, and gender identity in particular, some unique challenges arise that we must address before moving forward. The first challenge is the question of “why gender?” Why does gender, among the wide array of possible identities, warrant a unique discussion? If identity is indeed significant, then varying identities such as gender, race, or age, as well as their points of intersection, might also be of relevance for certain research topics. In these cases, being sensitive to the gender division alone might not be enough for a sufficient understanding of the focal phenomenon.

Without questioning the importance of other identities or the intersection between different identities, we believe that the criteria for deciding whether to account for any particular identity should be determined by the theoretical aim. Gender (or other identity) differences should be accounted for if the distinction in its current form is socially meaningful and if there are theoretical reasons to suspect that it may have an impact on the focal outcome. We suggest that gender be used as a starting point to understand the importance of accounting for identity in political science. The universal nature of gender, as well as its similarity across different contexts, makes it an excellent reference point for considering the impact of identity.

The second challenge, which is more relevant to quantitative analysis, is how to measure gender. Since the term “gender blindness” refers to gender as an identity, rather than merely sex, it addresses the lack of awareness of encompassing differences between men and women resulting from socialization to gendered norms and their stratifying outcomes (Dassonneville and McAllister Reference Dassonneville and McAllister2018; Kuhn Reference Kuhn, Ittel, Merkens, Stecher and Zinnecker2010; Trevor Reference Trevor1999). Nevertheless, in most current literature, gender is measured by a binary biological sex (McDermott and Hatemi Reference McDermott and Hatemi2011). Given the recognition of the nonbinary nature of gender, which has been drawing both public and scholarly attention, measuring gender as a binary sex is problematic. Indeed, in recent years, there has been growing critique of the binary approach to measuring gender (Bittner and Goodyear-Grant Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; Hatemi et al. Reference Hatemi, McDermott, Michael Bailey and Martin2012). Surveys using measures of sexual orientation and gender identity have recently come into use, but there is no consensus yet on how to introduce a nonbinary approach to quantitative methods (Markstedt et al. Reference Markstedt, Wängnerud, Solevid and Djerf-Pierre2021; Westbrook and Saperstein Reference Westbrook and Saperstein2015).

Although we miss cases that do not fall into the two dichotomous categories when referring to gender as a binary sex, we should bear in mind that quantitative analysis tends to focus on comparisons between large groups based on their measurable averages, and its ability to capture nuance comes at the cost of the sample size and therefore the validity of the findings and conclusions. Since, in most cases, attending to various identities requires distinguishing between the different identities, in the case of men and women, this means cutting the sample by about half. In the case of multiple identities, the cost would be to divide the sample even further, and in the case of nonbinary gender, the nonbinary groups could be very small, making the analysis inapplicable.

In summary, while there are both normative and practical costs to implementing gender-sensitive analysis as a sole and binary identity, none of this invalidates its possible benefits as long as the two binary gender groups persist as meaningful social categories. Therefore, neither the acknowledgment of the importance of other identities nor the recognition of the nonbinary nature of gender is contrary to our aim, which is to stress the significance of gender. Rather, if the gender binary identity plays a significant role, this could invite further inquiry about the significance of identity and gender in its diverse forms. In other words, our work could be a first step toward creating a greater awareness of gender in the field, which may encourage future research on the importance of accounting for nonbinary gender categories, as well as other identities.

Identifying Gender Blindness in Political Science Quantitative Research

As noted earlier, addressing gender blindness and applying gender-sensitive analysis is increasingly gaining recognition as an integral part of sound research practice in a variety of fields, including medicine, engineering (Hansen Reference Hansen2002), the exact sciences (Research Council of Norway 2017), and environmental and development studies (Leduc Reference Leduc2009). These fields have already begun to generate a body of literature and guidelines on combating gender blindness and applying gender-sensitive analysis to the research process.

Existing guidelines for gender-sensitive analysis in the fields mentioned here tend to focus on quantitative analysis (Hansen Reference Hansen2002; Leduc Reference Leduc2009; Research Council of Norway 2017). These guidelines are articulated by research funding organizations, government agencies, and peer-reviewed publications. They often detail the implementation of gender-sensitive analysis across all research stages: from the initial formulation of the research question(s), through the literature review, the research framework and hypotheses, to the choice of methodology and analysis.

Where gender differences are established in the literature, the research questions should account for it. When the literature is reviewed from a gender-sensitive perspective, the review should reveal whether gender has been found to interact with any of the concepts and topics under examination, and it should address how this interaction may affect the outcome. If gender does interact with the main study concepts, the analytical framework should be designed to reflect the different experiences of men and women (Jacobson Reference Jacobson1999; Leduc Reference Leduc2009; Research Council of Norway 2017).

The focal phenomenon itself should be examined for gender biases, as different operationalizations of a given variable can lead to different outcomes, and variables are not necessarily gender-neutral. For example, women and men differ both in the nature of the crimes that they commit and in the likelihood of being the victim of a specific crime (Steffensmeier and Allan Reference Steffensmeier and Allan1996). If crime is operationalized in terms of homicide rates, the research will observe a variable that affects men disproportionately. If crime is operationalized in terms of assault, especially sexual assault, the research will observe a variable that disproportionately affects women (Cooper and Smith Reference Cooper and Smith2011). This does not mean that crime should not be operationalized in terms of homicide or assault rates. However, in such cases, one should be aware that if gender is disregarded, the conclusions could be biased.

A gender-sensitive quantitative methodology requires a gender-representative sample and consideration of the gendered character of the dependent and independent variables (Llácer et al. Reference Llácer, Zunzunegui, del Amo, Mazarrasa and Bolůmar2007). When the focal variables do have a gendered dimension, the analysis should address this by, for example, disaggregating the sample by gender, or directly estimating the interaction with gender, to capture gender differences (Government of Canada 2018; Banyard, Williams, and Siegel Reference Banyard, Williams and Siegel2004).

In addition to the interaction, which addresses gender differences in the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, gender can also be added as a variable to the equation or as a control variable. In the former instance, the coefficient of gender is an estimation of the net gap between men and women with regard to the specific outcome. When “gender” is introduced gradually through a series of models, it can provide insights into the role of gender as a mediator. In other words, it shows whether part of the effect between the two variables under examination is explained by gender. In the latter instance, adding gender as a control eliminates the possible intervention of gender in the relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Considering factors such as theoretical framework, concepts, operationalization, types of variables, and the possibility of interactions, we propose a number of guiding questions for assessing gender blindness in quantitative research design:

-

1. Do we have theoretical reasons to expect gender differences in the relationship between the independent and dependent variables (or in the effect of the former on the latter)? If the existing literature implies that gender does affect outcomes, the omission of gender will be more costly to the validity of the research conclusions.Footnote 1

-

2. If so, is the analysis designed to capture gender differences (by a gender-disaggregated analysis or interaction)?Footnote 2

-

3. Are gendered dimensions of the independent or dependent variables taken into account in the sample selection and in the way the variables are operationalized?

-

4. Can gender be included as a control in nondisaggregated models as a means of controlling for the way in which gender may account for part of the association between the independent and dependent variables?

Using this list of considerations, we progress to our two-stage analysis: we first demonstrate the impact of gender blindness on results, and then we estimate the prevalence of gender blindness within political science quantitative research.

We chose the AJPS for our study for substantive as well as practical reasons. The AJPS has consistently been ranked as a leading political science journal by the Clarivate Journal Citations report for many years. The journal publishes in all major areas of political science, including international relations, comparative politics, and public administration. In substantive terms, its high rank, along with its commitment to covering a broad range of subfields, makes it a prime candidate for positing the extent to which gender blindness is present in mainstream political science research. In practical terms, unlike most other journals, the AJPS requires that all authors make available both their data and their coding. Authors must do this using the Harvard Dataverse data repository. This uniform method of publishing both data and code provides a high level of accessibility, which means that studies published in the AJPS can be reproduced with relative ease. Although the requirement to share both data and code is found in some other journals, it is by no means universal.

Stage 1: What is the Potential Impact of Gender Blindness?

In the first stage of our study, we provide illustrative examples of the impact of gender blindness on results to demonstrate how gender-sensitive analysis can lead to more precise outcomes. We randomly chose three articles from a total of 19 that, of all the articles published in the AJPS in 2018 and 2019, met a number of criteria. First, these quantitative articles were identified as exhibiting gender blindness according to the points mentioned earlier. Second, their data included information on the sex of participants, and their samples included a sufficient number of men and women to run separate models. Finally, the method and coding were relatively straightforward, and we had the required expertise to recreate the analysis, ensuring a minimal possibility of error during replication.

For each study, we first replicated the original findings to confirm that we understood the methodology thoroughly and had the tools to alter the original research design. Following successful replication, we then generated the same analyses and models using gender-sensitive analysis techniques, which involved recreating the models using gender-disaggregated data.

In two of the three articles, we found that a gender-sensitive analysis changed the results and conclusions. Next, we start with a short description of the research questions and results of each study, followed by a discussion of the potential impact of gender and the findings of the new sex-disaggregated analyses.

Demonstrating the Impact of Gender-Sensitive Analysis on Outcomes

Article 1: Committed or Conditional Democrats? Opposition Dynamics in Electoral Autocracies (Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong 2019 )

In October 2019, Gandhi and Ong published an article exploring the extent to which voters are committed to defeating autocratic incumbents, even in the face of less than desirable electoral outcomes. They asked whether voters would be willing to support a coalition that included their preferred party but would allocate primary leadership roles and preferences to a different party in the coalition in the event of victory. They hypothesized that voters’ willingness to support a coalition in such a scenario would depend on whether they had an ideologically similar alternative outside the coalition in question.

The authors tested their hypothesis by conducting a survey experiment prior to the May 2018 election in Malaysia. Malaysia has an incumbent ruling coalition, the Barisan Nasional (BN), known for its repressive tactics against opposition politicians and its manipulation of electoral rules. Before the election, an opposition alliance, the Pakatan Harapan (PH), was formed. The two largest parties in the alliance, Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (BERSATU) and the Democratic Action Party (DAP), were also the most ideologically distant. BERSATU is a splinter party from the United Malays National Organization (UMNO). BERSATU supporters who chose to abandon the party could therefore return to the ideologically and politically similar UMNO. Supporters of the DAP, on the other hand, had no ideologically similar parties representing their interests outside the PH.

In the survey experiment, respondents were given a prompt, telling them that if the PH parties were to run separately, the BN would probably win the election. They were then asked how likely they were to vote for a PH coalition member. This prompt established a baseline of support for the coalition. Respondents were then given prompts explaining that if the opposition coalition won, the other party and not the one they supported would secure the premiership. Respondents were then once again asked whether they would support the PH. The authors then ran a difference-in-difference analysis to observe the changes in responses among the different types of supporters before and after the treatment.

The findings showed that BERSATU supporters were highly likely to withdraw their support for the PH if the DAP were to win the most seats and the premiership. In contrast, there was no significant change in DAP supporter backing of the PH in the case of a BERSATU win. The findings supported the hypothesis that voters’ willingness to support a coalition depends on the terms of the coalition victory, in interaction with ideological alternatives for the voters. If given the opportunity to oust an autocratic or corrupt party or coalition, voters will not necessarily do so if that means compromising the standing of their favored party. The authors concluded that voter behavior could be a primary explanatory force for the failure of opposition coalitions to form and engage in compromise.

Based on the list of considerations given earlier, we identify several points that relate to gender blindness. The survey sample lacked gender balance, as 63.4% of the participants were male. The models did not control for the gender of the respondents, which can be critical if a sample is not gender representative. More importantly in this regard, the study did not account for the possibility that men and women might react differently to the prompt. If there is a theoretical reason to expect gender differences in the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, then the method should account for such a possibility.

There are a number of reasons to expect gender differences in the context of this article. First, strategic voting—that is, the act of voting for someone other than a voter’s first-choice candidate to increase the chances of an outcome that, on the whole, will be more satisfactory for the voter—follows gendered patterns. Women are more likely to engage in strategic voting (Lee and Rich Reference Lee and Rich2018; Shaw, McKenzie, and Underwood Reference Shaw, McKenzie and Underwood2005). Second, findings have demonstrated that women are generally more inclined to compromise than men (Nikolova and Lamberton Reference Nikolova and Lamberton2016), though this was not tested specifically in this context. This could impact women’s willingness to engage in coalition politics, even if the coalition format is not ideal.

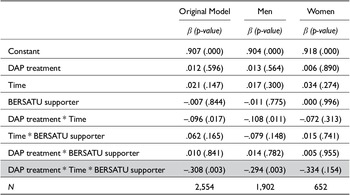

Based on these theoretical expectations, we recreated the first round of models, which analyzed BERSATU and DAP supporter behavior. Once we confirmed the original findings, we ran the models again, using gender-disaggregated data to test the possibility that the effect varies by gender. Table 1a presents both the original and the gender-sensitive results for respondents exposed to the prompt describing a DAP win. The variable of interest is the interaction between treatment, time, and party (highlighted in the table). In the original model, this variable was significant; in the sex-disaggregated models, however, it was significant only for men.

Table 1a. Difference-in-difference estimations of coalition support for supporters of BERSATU versus other coalition parties: Original and sex disaggregated

Table 1b shows the results for respondents exposed to the BERSATU prompt. In this case, the variable of interest—which tested the likelihood of DAP supporters leaving the coalition—was insignificant. In the disaggregated models, it continued to be insignificant for both men and women.

Table 1b. Difference-in-difference estimations of coalition support for supporters of DAP versus other coalition parties: Original and sex disaggregated

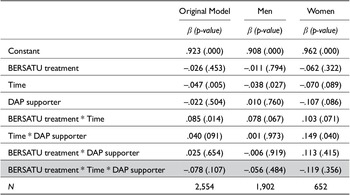

Figure 1 presents the differences between the original and the gender-disaggregated models. Panels A and B show the original and gender-disaggregated results for BERSATU voters, respectively. As Panel B shows, we found that among BERSATU supporters, only men were likely to leave the coalition in the case of a DAP premiership. Panels C and D show the original and sex-disaggregated results for DAP voters, respectively. The original finding that DAP supporters would not change their vote in case of a BERSATU premiership (Panel C) remained the same for both men and women when gender-sensitive analysis was applied (Panel D).

Figure 1. Outcomes of original and sex-disaggregated models for Ghandi and Ong (Reference Gandhi and Ong2019).

In summary, both women and men stay with the coalition when they do not have an ideological alternative. However, if men have an ideological alternative, they will abandon the coalition to avoid compromise. Women will stay with the coalition even if their preferred party will not lead it, regardless of the ideological alternatives. Because the survey sample was skewed in terms of a preponderance of male participants, the effect among men dominated the results and obscured the conclusion that this effect is relevant for male voters, but not for female voters. Thus, the gender-disaggregated models not only provide more accurate insight into voter behavior and coalition politics, they also validate and concretize the findings of the existing literature, which shows that women are more likely to engage in strategic voting than men (Lee and Rich Reference Lee and Rich2018; Shaw, McKenzie, and Underwood Reference Shaw, McKenzie and Underwood2005).

Article 2: The Economic Consequences of Partisanship in a Polarized Era (McConnell et al. Reference McConnell, Margalit, Malhotra and Levendusky 2018 )

In January 2018, McConnell et al. published an article exploring how partisan division affects economic behavior. They hypothesized that a similar or contrary partisan alignment between two individuals would affect pecuniary or professional gains. Identifying or being at odds with an employer’s partisan alignment would impact both the remuneration that a person would request, as well as the quality of their work.

The researchers conducted a number of field and survey experiments. In their first experiment, they tested how partisan alignment affects both the wages requested by individuals and the quality of their work. The researchers posed as a nonprofit organization offering freelance copyeditors a job editing website content. Some copyeditors were given content that expressed a clear partisan alignment with the founders of the nonprofit organization, while others received content that expressed no partisan leaning. The copyeditors were then asked a number of questions, including questions whose answers would indicate their political alignment. The researchers measured (1) how much money the copyeditors required to do a similar job in the future for the same employer; (2) the number of embedded errors that each copyeditor caught; and (3) the total number of changes they made. They then checked the correlation between these variables and the copartisan or counterpartisan alignment between the copyeditor and the fictitious nonprofit founders. The research team followed up this experiment with two further experiments focusing on consumer behavior and incentives to collect monetary gains versus the expression of partisan alignment.

Of the variables in this experiment, reservation wage (1) and total edits (3) were consistently predicted by the copyeditors’ political alignment, but only in relation to copartisanship. Copyeditors were likely to give a lower price offer to copartisans, although they were not likely to ask for more money from a counterpartisan than they would have from a neutral employer. Editors were also likely to make fewer corrections, find fewer faults, and make fewer changes in the original text when editing for a copartisan. The researchers concluded that partisan standing not only affects relationships in the realm of politics, but also spills over to economic behavior.

The implicit assumption in such a research design is that the association between political identity and economic behavior is not affected by gender. This assumption, however, disregards studies showing that men and women differ in their modes of political participation and cooperation (Coffé and Bolzendahl Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010; Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer2012). For example, it is inconsistent with the findings that in dealings between counterpartisans, female politicians are more likely than male politicians to participate in activities that foster collegiality (Lawless, Theriault, and Guthrie Reference Lawless, Theriault and Guthrie2018). Men and women also express their political leanings differently. For example, Coffé and Bolzendahl (Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010) found that men are more likely to be active in political parties and express political opinions publicly, while women are more likely to vote and engage in “private” activism. Women have also been found to more strongly hold different identities, particularly party identities (Ondercin Reference Ondercin2018; Ondercin and Lizotte Reference Ondercin and Lizotte2021). Given the differences in the ways that men and women express their political leanings, they may also differ in the way that they express their political alignment in personal interactions and in workplace relationships.

The underlying assumptions also disregarded differences between men and women in the economic arena with regard to wage levels, salary expectations, and workload (Ausburg, Hinz, and Sauer Reference Ausburg, Hinz and Sauer2017; Barron Reference Barron2003; Miller and Vagins Reference Miller and Vagins2018; Pascall and Lewis Reference Pascall and Lewis2004). Given that wage request was a central dependent variable, it is important to take into account that men tend to make higher salary requests and have higher salary expectations than women (Hernandez-Arenaz and Nagore Reference Hernandez-Arenaz, Nagore and Hamilton2019; Mazei et al. Reference Mazei, Hüffmeier, Freund and Stuhlmacher2015).

We recreated the study’s models using sex-disaggregated data, with separate models for women and men. The results are presented in Table 2. The table is divided into two parts, with copartisan and counterpartisan results, respectively, grouped together. Within these groups, rows present the results for the three samples. In the case of counterpartisanship, insignificant effects were found in all three original models, as well as in the separate models.

Table 2. The effect of employer partisanship on employee behavior

Notes: Data in the table are based on the authors’ main models. Robustness tests, which confirmed results, can be found in the original article. Two observations were dropped during the reanalysis because of missing data on gender.

In the case of copartisanship, on the other hand, the sex-disaggregated models revealed remarkable differences in the behavior of women and men. For all three variables, the effect size among women is much greater. In the original co partisan models, a significant effect was found for wages demanded and total edits made. When tested separately, we identified that the effect of both variables was based solely on the tendency of women—and not men—to respond to partisan alignment. The inclusion of men suppressed the total effect; thus, when the genders were tested separately, the effect increased for women and decreased and became insignificant for men.

Similar results were found for the number of errors caught. In the original, the relationship between copartisan alignment and errors caught was insignificant. When tested separately, the effect size of the variable again increased dramatically for women, becoming significant (under p < 0.10), but remained insignificant for men. With regard to the total edits variable, again, the effect size for women was larger than for men, and so was the significance level, although the reduction of the sample to half of its size greatly impacted the significance levels.

Women’s tendency to respond to a copartisan relationship supports other findings regarding women’s sentiments toward cooperation and collegial behavior in politics (Ausburg, Hinz, and Sauer Reference Ausburg, Hinz and Sauer2017; Barron Reference Barron2003; Lawless, Theriault, and Guthrie Reference Lawless, Theriault and Guthrie2018). In this case, it shows that women’s economic behavior is affected by their perception of political relationships, specifically a perception of shared identity. Men’s economic behavior, on the other hand, seems to be unaffected by partisan alignment or polarization.

The authors concluded that their results lend support to theories of in-party affinity, but diverge from the existing literature regarding effective polarization and out-party aversion. The sex-disaggregated models, however, imply that the authors’ conclusions regarding in-party affinity are more applicable to women than to men.

Article 3: Ethnic Parties, Ethnic Tensions? Results of an Original Election Panel Study (Fleskin 2018)

In September 2018, Fleskin published a study examining how ethnic political mobilization impacts national unity. The author hypothesized that for a majority group, ethnic mobilization will increase in-group identification, aversion to the out-group, and national identification. In the case of minorities, political mobilization was hypothesized to increase in-group identification and out-group aversion, but to negatively impact national identification.

The researcher used a survey of Romanian voters conducted a few weeks before and a few weeks after a national election. During the election, political parties had mobilized along ethnic lines. This worked as a treatment to expose voters to ethnic political mobilization. Three groups of voters were tested: ethnic Romanians in counties with a Romanian majority, ethnic Hungarians in counties with a Hungarian majority, and ethnic Romanians in counties with a Hungarian majority. The results showed that while sentiments of in-group identity increased with ethnic political mobilization, out-group aversion did not increase. In fact, there was increased sympathy for out-group members among all groups. Contrary to expectations, national identification also increased for all groups.

Existing studies on gender and ethnic identity as well as gender and political behavior imply that gender could influence the relationship between ethnic political mobilization and individuals’ in-group and out-group relations. Gender determines how individuals define themselves in ethnic and cultural context, and how they choose to process ethnic identity and in-group characteristics (Qin Reference Qin2009). Gender also influences modes of political participation and political identity (Cassino and Besen-Cassino Reference Cassino and Besen-Cassino2021). Based on our knowledge that gender affects both ethnic identity and political behavior, we might expect gender to affect the association between the two. However, we did not find any literature that implies that men and women differ in the way that politics impacts ethnic identity, or vice versa. While there were grounds for hypothesizing on gender differences based on gender differences in ethnic identification and political behavior, it was not clear whether we should expect gender differences in this context. With that in mind, we recreated the original models using sex-disaggregated data, with separate models for women and men.

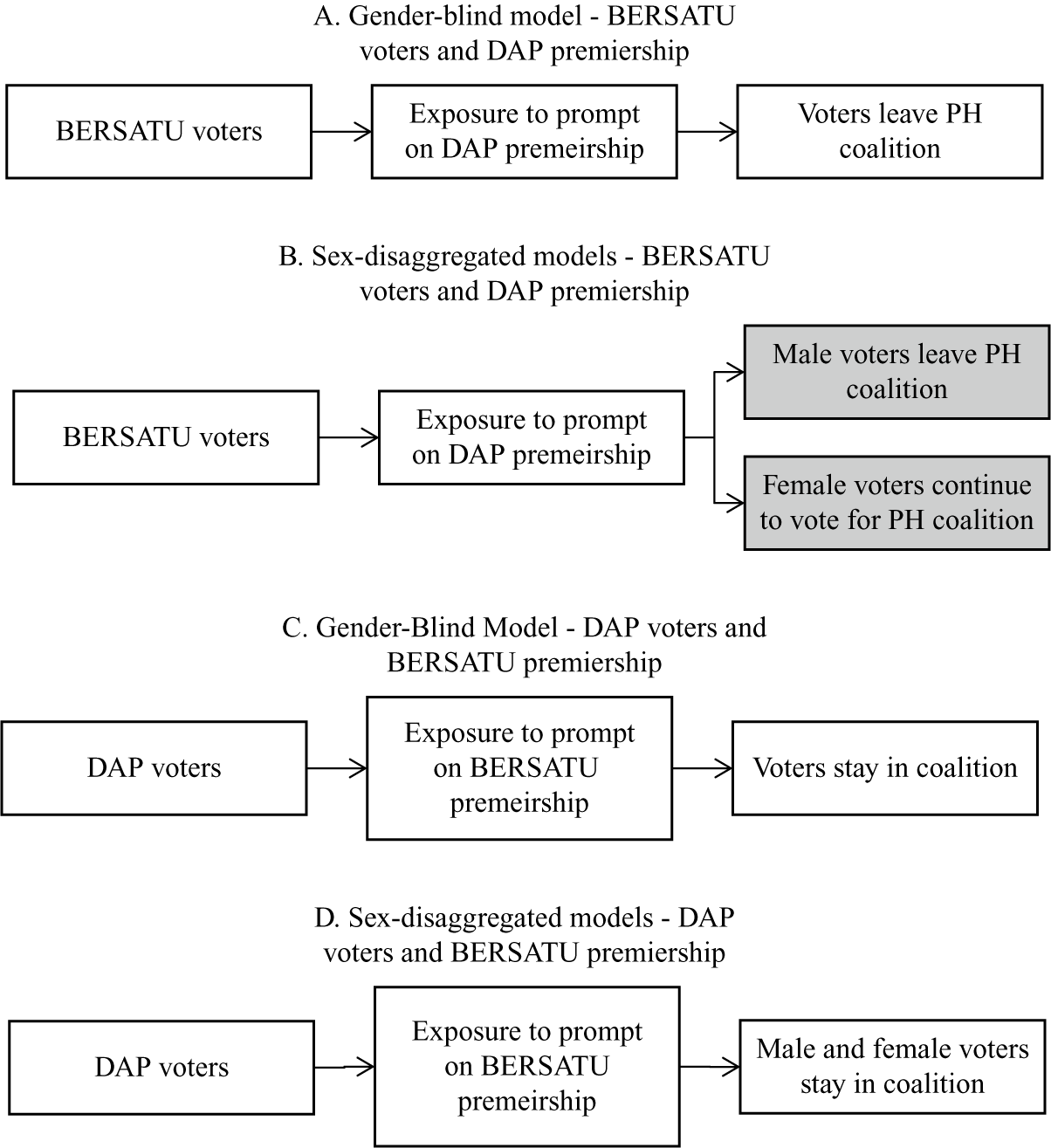

Figure 2 presents both the original analyses as presented in the paper and the new sex-disaggregated analyses. It shows the change in the average response to questions of importance regarding personal ethnic identity and feelings about members of the in-group on a scale of 1–10 before and after the election. Panel A shows the original results: both minority and majority groups felt an increase in in-group identification, although the size of the effect varied. Panel B shows the result broken down by gender. In all three groups, men and women had very similar survey results both before and after the election.

Figure 2. In-group identification, original and sex-disaggregated.

Figure 3 presents both the original and the sex-disaggregated results of analyses of attitudes toward the out-group. Respondents were asked before and after the election how they evaluate members of the other group on a 10-point scale. Again, in all three groups, men and women had remarkably similar survey results both before and after the election. Even with the addition of sex-disaggregated data, the original conclusions held for both men and women.

Figure 3. Out-group attitudes, original and sex disaggregated.

In this example, we found a marked similarity between the gender groups in the effect of ethnic mobilization on in-group or out-group identification. Although gender has been found to affect both ethnic identity (Qin Reference Qin2009) and political behavior (Cassino and Besen-Cassino Reference Cassino and Besen-Cassino2021), it did not affect the association between the two. Rather, the similarity between the gender groups is striking, and this in itself is an important finding.

Stage 2: Prevalence of Gender Blindness in Political Science

Methodology and Findings

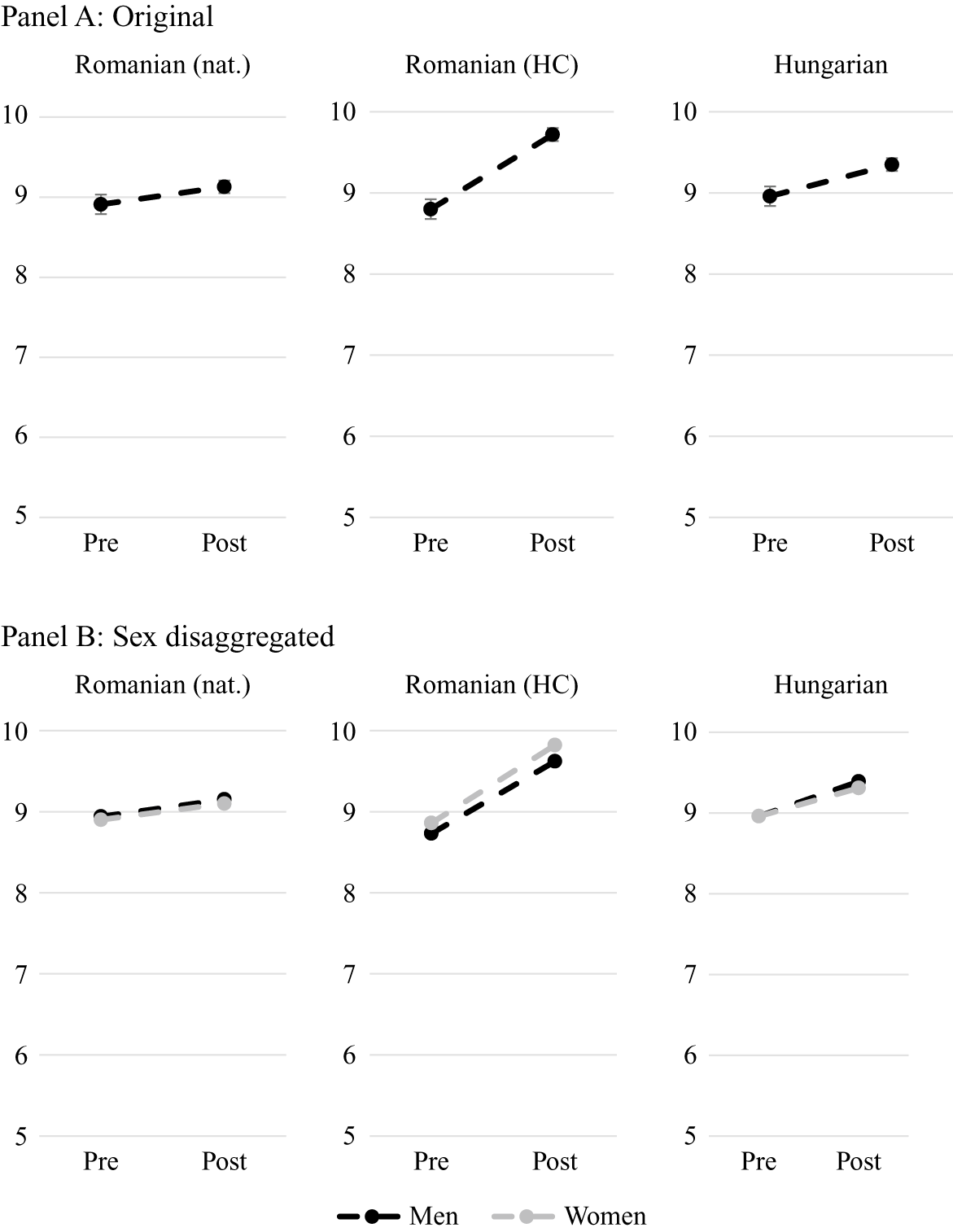

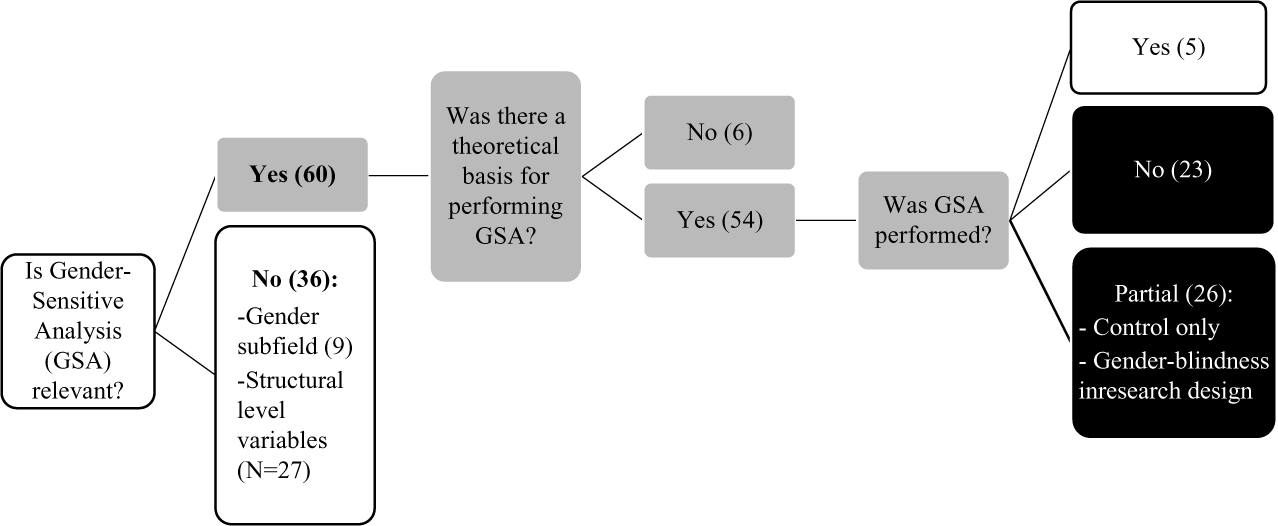

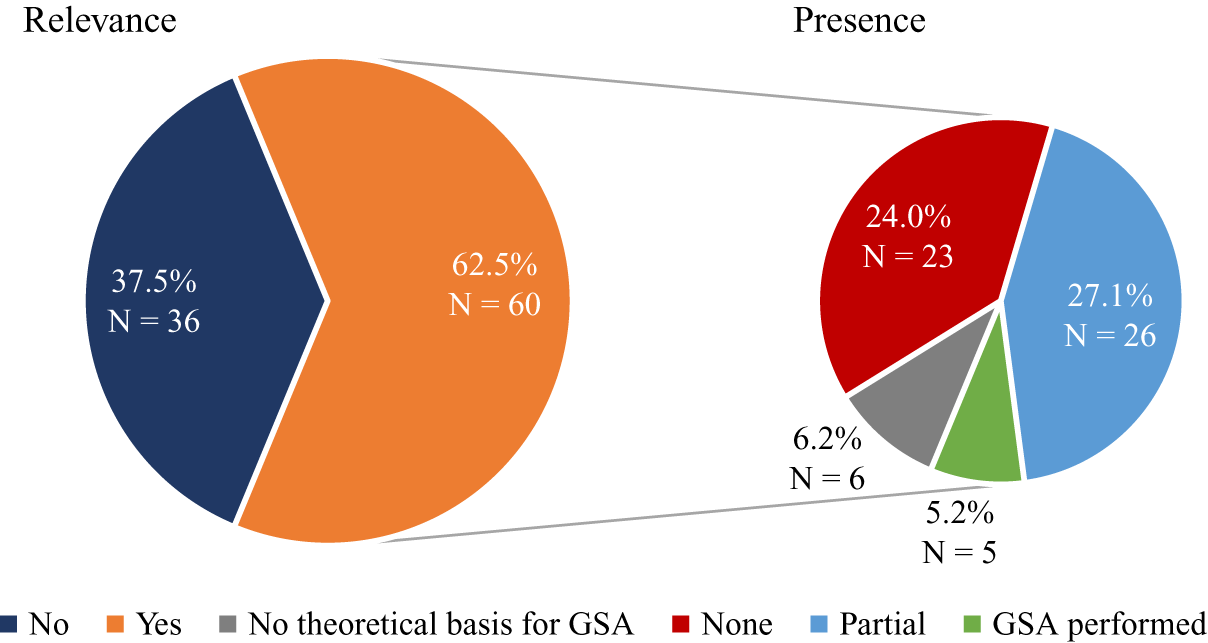

Our second aim was to estimate the extent to which mainstream political science suffers from gender blindness. To this end, we reviewed every article published by the AJPS in 2018 and 2019. Out of a total 114 articles, we focus on the 96 empirical articles that used quantitative methodology. Figure 4 displays the breakdown into different categories that guide the analysis. We first divided these 96 articles into two categories. The first category—represented by boxes marked in white—consisted of articles for which gender-sensitive analysis was not relevant (N = 36). This category was made up of two types of articles: articles anchored within the gender subfield (N = 9), and articles whose research questions and units of analysis focused on the institutional or structural level (N = 27).

Figure 4. Process for categorizing quantitative articles to assess for gender blindness (N = 96).

Articles from the gender subfield were included in this category if (1) they focused on women only and therefore drew their conclusions only for women, and if (2) gender was the primary focus of the article, making it not gender-blind by definition. An example of the latter is Kim’s (Reference Kim2019) article on how different forms of direct democracy impact the gender gap in political participation. The second group of articles that are ineligible for gender-sensitive analysis includes those whose units of observation were at the institutional level, that relied on case studies, that discussed a methodological question, or that considered the activity of participants in a historical event without any female participants.Footnote 3

The remaining articles (N = 60)—represented by boxes shaded gray—were quantitative studies that could be gender-blind. In other words, their units of analysis had gendered dimensions, which may or may not have been taken into account, and gender as a moderating variable may or may not have been considered. For every article, we carried out an overview of the literature to see whether there was a theoretical basis for hypothesizing that gender could be a defining factor and influence the results. We did not want to classify an article as gender-blind if there was no existing theoretical basis for expecting gender to be relevant to the subject. For example, when analyzing an article that explored how the public defines terrorism (Huff and Kertzer Reference Huff and Kertzer2018), we found no previous literature to support an assumption that men and women approach terrorism differently. This resulted in two groups of articles: those whose literature has either not yet explored gender or considered it and found that it is not a significant factor in the specific field (N = 6), and those whose field of literature has considered the issue of gender and found it to be significant (N = 54).

Of the 54 articles, 5 included gender-sensitive analysis. The articles classified as presenting a gender-sensitive analysis were those whose research design accounted for gender differences in the focal effect, for example, by a sex-disaggregated analysis of the data or by the inclusion of an interaction term with gender. They constituted 5.2% of all the quantitative articles published in 2018 and 2019 in the AJPS, and 8.3% of the pool of 60 quantitative articles that were candidates for gender-sensitive analysis (see Figure 5). The remaining articles (N = 49), marked in black in Figure 2, had either none (N = 23) or only partial gender-sensitive analysis (N = 26).

Figure 5. Relevance and presence of gender-sensitive analysis in quantitative articles (N = 96).

The 26 articles that had partial gender-sensitive analysis constitute 43% of the 60 articles that could be influenced by gender blindness and 27.1% of the total pool of 96 quantitative articles. Articles were considered partially gender-blind if they met either of two conditions, relating to the independent or to a dependent variable, respectively. First, if the article only included a control variable for gender: although the aim of such a control variable is to “exclude” a possible effect of gender from the relationship between the two focal variables, the coefficient of gender nevertheless can provide information about gender differences in the dependent variable. Second, in some cases, we defined an article as partially gender-blind because the research design was gender-blind. Notwithstanding that some of these articles included gender controls or even featured sex-disaggregated models or models with interactions, their research design introduced gender blindness. Most of these studies were survey experiments in which the vignette featured only male characters or the dependent variable was operationalized in a way that captured a predominantly male experience (for example, see note 2 herein).

In all, 23 articles were fully gender-blind, meaning that while one or more of the study’s variables had a gender dimension, the article had no gender-sensitive analysis and did not control for gender. They represent 38.3% of the pool of 60 quantitative articles that were candidates for gender-sensitive analysis and 24% of the total pool of 96 quantitative articles.

In summary, more than half the articles we examined were candidates for gender-sensitive analysis; of these, the vast majority overlooked the potential influence of gender. Out of the total 96 quantitative studies published in a two-year span in the AJPS, 51.1% (N = 49) were either partially or fully gender-blind. This represents 81.7% of the 60 articles that could have included gender-sensitive analysis in the quantitative research framework and for which the existing literature suggests that gender could affect outcomes.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we aimed to demonstrate the potential impact of gender blindness and to estimate its prevalence in mainstream political science research. Using two years of publications from the AJPS, we recreated a number of studies using gender-sensitive analysis to show its implications for results and conclusions. We then reviewed every article published within this two-year span and assessed them for gender blindness to ascertain its prevalence.

Our findings show that gender-sensitive analysis yields more accurate and useful results. In two out of the three articles we tested, gender-sensitive analysis indeed led to different outcomes that changed the ramifications for theory building as a result. We have also saw that the majority of quantitative articles (51.1%, N = 49) published in the AJPS in the two years under observation had some elements of gender blindness and were potentially impacted by gender blindness.

In the first revised study, gender-sensitive analysis changed the final results in accordance with existing knowledge on gendered differences in strategic voting behavior. In this study of Malaysian voters, we found that while male voters were indeed unlikely to compromise on policy and party ideology to move toward democracy, female voters were likely to do so. The original findings essentially presented the weighted average between the positive effect for men and the insignificant effect for women. The gender imbalance in the sample, with its preponderance of men, allowed for a significant result overall. Thus, the study’s original conclusions—that voters would leave a coalition if the terms were not in their favor and if they have an ideological alternative—is true for male voters but not for female voters.

For the literature on coalition formation, this finding has theoretical as well as compelling practical implications. It indicates that an increase in female voters may lower the cost of forming opposition coalitions, as party leaders will be penalized less for making coalition compromises. In these cases, such coalitions will have a better chance of beating the ruling coalition or party in elections. Acknowledging the different voting patterns of men and women in this context could be a first step toward creating a potentially useful tool for encouraging such coalitions.

In the case of the second article on partisanship and economic activity, previous knowledge about how men and women differ in both political and workforce behavior implies that gender could interact with the way that partisan identity impacts economic behavior. Our gender-disaggregated analysis changed the outcomes of the original study, reinforcing previous findings that men and women express political identity differently and behave differently in the workforce. We found that for women, copartisan relationships impacted every measure of work activity. Men, on the other hand, were uninfluenced by partisan identity alignment. The significance of the variables as found in the original article was therefore the result of women’s behavior; the inclusion of men in the original models weakened the effect size.

These revised findings add to the literature on partisan politics, political economics, and identity politics, and have a number of potential practical applications. They change the results and give a clearer picture of the interaction between partisan politics and economic behavior, taking into account the fact that women are more likely than men to allow partisan identity and alignment to affect decisions taken outside of political discourse. The findings also provide insight into the gendered nature of economic activity. Women seem to be more influenced by a sense of in-group identity when pursuing economic interests, as indicated by their reduced wage demands with respect to copartisans. While findings have often shown that women generally request lower wages than men, the findings presented here offer a new consideration and an alternative perspective. Women’s workforce behavior could be intertwined with their political behavior and processes of gendered political socialization.

Regarding the third study, although the existing literature has found that gender impacts ethnic identity, as well as political behavior, we found no gender differences in the association between the two. This null finding, though, has important implications in its own right. When we consider questions of intersectionality in determining political identity and behavior, this finding—which underscores the significance of ethnic over gender identity in determining political outcomes—adds critical information. Ethnic identity may be a stronger factor than gender in determining political behavior. Additionally, strategic efforts at political mobilization could find voters’ sense of ethnic identity particularly amenable to manipulation. Other forms of cultural and political socialization, such as gender, do not impact the strength of ethnic mobilization.

Having established the significant benefits that gender-sensitive analysis could have, we went on to estimate the potential prevalence of gender blindness. In more than half the papers published within our two-year span (n = 114), the research design had gendered elements. Despite this, only a very small number (n = 5) fully accounted for gender. The vast majority either fully or partially disregarded gender. This indeed confirms the suspicion that as a whole political science research may be characterized by methodological norms that disregard gender. Feminist political scientists that have expressed concern regarding an indifference to the impact of gender may have identified a real cause for unease.

The articles whose outcomes we have revised in this article illustrate how a consideration of gender, and the inclusion of gender-sensitive analysis, can refine our understanding of phenomena. On a theoretical level, this understanding may produce more useful typologies, theories, and concepts. From a practical perspective, taking gender differences into account can improve our understanding of the needs and behaviors of different groups, and can contribute to more sustainable and successful public policy making. Given the large impact that gender-sensitive analysis can have on outcomes, as demonstrated by two of our cases, the fact that 51.1% of the quantitative studies published in the field’s leading journal use research designs characterized by gender blindness, despite the literature indicating the relevance of gender, certainly suggests a reconsideration of field norms and practices.

This is not to say that gender analysis is required, or possible, for every research question, or that men and women always display different political behaviors. We do recognize that gender might not be of interest, or that there may not be any theoretical reason to expect gender to interact with the phenomenon at focus. That said, given the existing knowledge that gender is often a determinant or a moderator of political behavior and outcomes, we seek to motivate researchers to pay more attention to its theoretical and empirical significance. Our study, then, serves as a starting point for considering gender-sensitive analysis in political science quantitative research. In demonstrating its potential importance, we have aimed to bring political science into the wider discussion of gender blindness that has already begun in other fields. This first step, we hope, will strengthen the understanding of the importance of gender and highlight the need to better understand how gender-sensitive analysis should be applied to mainstream political science.

Defining this study as a “starting point” is also relevant as we have only examined a single journal. We chose the AJPS because of its status as a leading journal in the field, as well as its practical requirement of all authors to make both data and code available for reproduction. That said, such a study can and perhaps should be done for and by other journals. This would both improve the accuracy of the estimate presented here, and perhaps bring a wider circle of researchers, editors and publishers into the discussion of gender blindness.

We would also encourage readers to see this study as a starting point not only for considering gender, but perhaps also for building a toolbox to assess the significance of other identities or demographic groups that act as moderating variables. The criteria developed here for assessing gender blindness and applying gender-sensitive analysis could help address additional methodological questions related to identity. In addition to gender, demographic features such as race, ethnicity, and religion can also moderate results. Whereas a certain universality applies to gender, while race, religious and ethnic relations can be more context-specific, these latter criteria might still be useful when researchers design their studies.

As another note for future research, we also propose looking at how these guidelines function when more complex conceptualizations of gender are considered, including questions of intersectionality and nonbinary approaches to gender. We must consider how to account for multiple sources of identity and categories of gender identity, while not allowing this to become a roadblock for quantitative method by demanding a multitude of identity categories. This has both theoretical significance, in terms of how we understand gender, as well as practical significance in if and how data can be collected and analyzed in a way that captures intersectional identities. Future research must also engage with literature on new practices in measuring gender, especially in surveys and other methods of data collection commonly used for quantitative analysis.