Introduction

Today, the West Nordic societies are being tested to resist the new wave of great power rivalry, overcome the colonial legacy, and ensure their security. Amid such a situation, their sovereignty practices develop within the logic of patronage or the model of Patron-Client relations. This model was pertinent for political science debates during the Cold War when the US and the USSR established the systems of satellite states (Carney, Reference Carney1989). The power balance shift revives the model’s applicability for understanding the relations between the influential states and their smaller partners. We take this model as a theoretical background for our research. The key research question of the article is: What is the perspective for the West Nordic practices of sovereignty in the framework of their relations with great powers: Russia and China, as patron’s adversary states, and the US as a patron state? We are questioning if any of the two US opponents aspire to provide patronage for West Nordic societies and what determines alarmist reaction and disapproval of Russia or China initiatives.

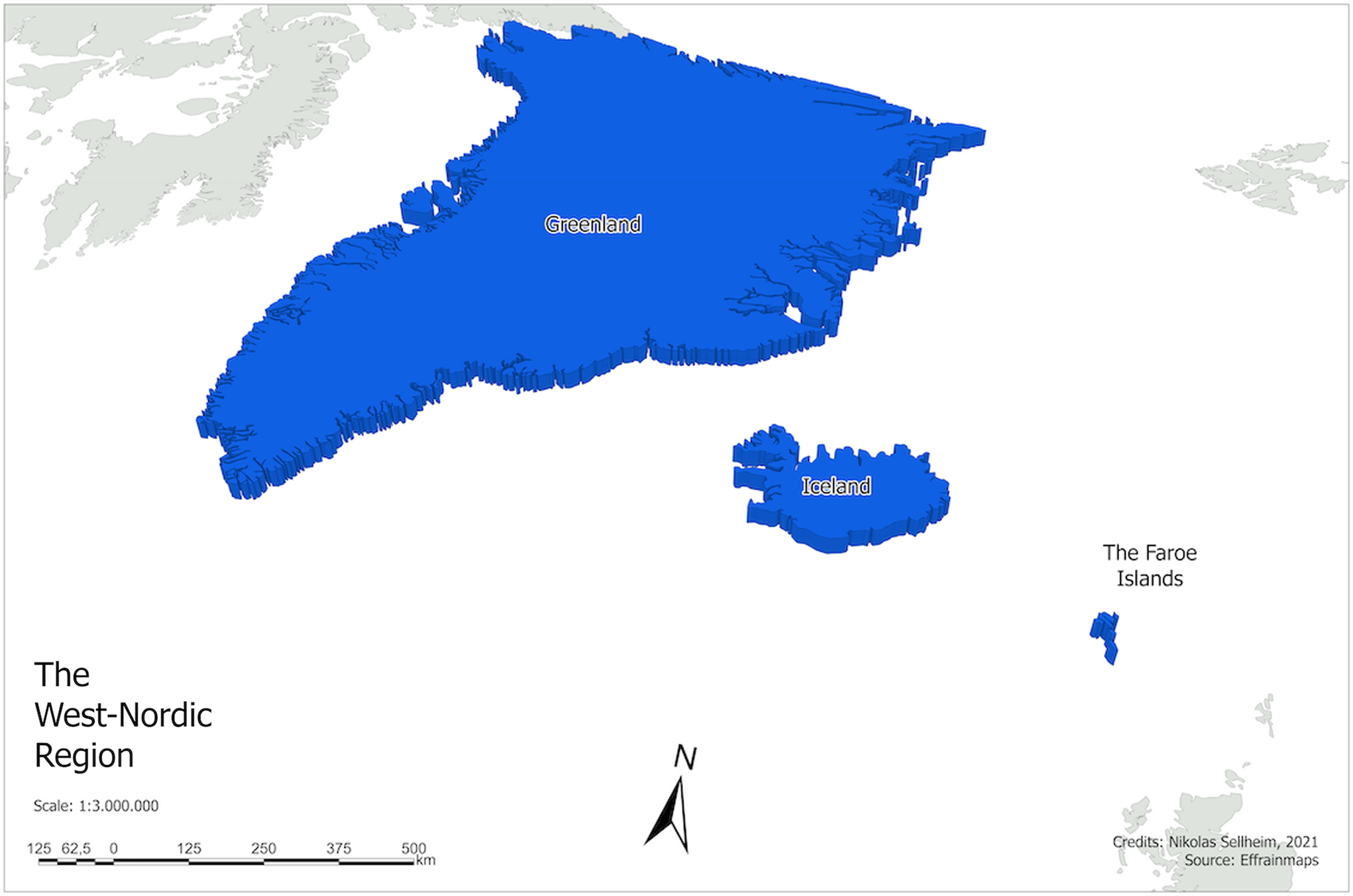

The destiny of the West Nordic small societies has been historically connected to geography (Cohen, Reference Cohen2015). The extraordinary location which binds Europe and America across shipping, aviation, and now space keeps the region in the spotlight of great power competition (see Fig. 1). From the Napoleonic Wars, when the British repeatedly considered the annexation of Iceland to ensure UK navy predominance over France, to World Wars, and the Cold War, when a natural gap from Greenland to the United Kingdom, the so-called GIUK ridge (an acronym for Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom) played an essential role in the allies’ security (Agnarsdóttir, Reference Agnarsdóttir, Kouri and Olesen2016; Østhagen, Reference Østhagen2019). Subsequently, the security patronage over the region descended from imperial Denmark and Britain to the US (Bertelsen, Reference Bertelsen and Zellen2013; The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019; Vaicekauskaitė, Reference Vaicekauskaitė, Brady and Thorhallsson2021). Every world order alteration incited new challenges for the three North Atlantic societies.

Fig. 1. The West-Nordic Region.

At the same time, amid great power competition, Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands made headway in their struggle for sovereignty. Iceland attained sovereignty and independence from Denmark in 1918 sharing a monarchy and declared a republic in 1944. Greenland and the Faroe Islands are self-governing overseas autonomies in the Kingdom of Denmark (Sørensen, Reference Sørensen1979). In the coming years, the Government of Greenland will consider establishing a Free Association with Denmark (Arctic Circle, Reference Circle2021).

During the Cold War, the three societies accumulated bargaining experience in relations with the two great powers, the US and USSR. Today, they are gradually developing their own security and international politics, including in the Arctic, though still largely dependent on the US and NATO allies (High North News, 2020; Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2020). Due to economic and financial troubles, as happened in 2008 for Iceland, West Nordic societies turned to a more balanced and pragmatic approach to international cooperation. This included relations with countries like Russia and China, reputed as US adversaries.

The shift from US-led unipolarity to multipolarity or Sino-American bipolarity complicated Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland’s affairs with Russia and China (Colgan & Keohane, Reference Colgan and Keohane2017; Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2019; McConville, Reference McConville2021; Staun, Reference Staun2020). Today, with the ongoing military conflict in Ukraine, the West Nordic societies find themselves completely drawn into great power competition. The above affects the small societies’ sovereignty practices.

In the paper, we refer to David Sylvan and Stephen Majeski who describe the US as an empire of client states that holds sway over 40% of the world. Since 1948, this formation has included the Kingdom of Denmark and Iceland (Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009b). Even if the term “empire” is arguable, the Patron-Client model chosen by the authors plausibly illustrates the logic of the US relations with small allies – the ones that depend on its security coverage or “shelter,” as it was interpreted for the West Nordic region (Ingebritsen, Reference Ingebritsen, Ingebritsen, Neumann, Gstohl and Beyer2006; Thorhallsson & Gunnarsson, Reference Thorhallsson and Gunnarsson2017).

According to this premise, we consider the US as a patron and the three West Nordic societies as clients. We largely omit Denmark’s role in the discussion due to its in-between position. Being a close ally and a client of the US, the Kingdom of Denmark acts as a junior patron for its West Nordic clients and a mediator who settles the issues in line with the major patron’s interests. Denmark curates Faroes and Greenlandic policies, specifically in the security domain, with no decisive role in the cases discussed (Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009b). In turn, Russia and China are addressed as the US’s adversaries, one traditional, and the other a new one, respectively. In the article, we focus on the bargaining experience of the West Nordic societies in relation to the three influential states. We also examine cases where the US as a patron forced the client’s decision-making in line with its own geopolitical vision. Analysis of those relations through the lens of the Patron-Client model should be illustrative for tracing how the power balance shift influences practices of sovereignty in the West Nordic.

We start the article with an insight into a model of Patron-Client relations referring to the West Nordic case. In this vein, we discuss the issue of sovereign inequality between patron and client and suggest a perspective for the future practices of sovereignty in the West Nordic societies. In the two following parts, we evaluate the relations of Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland with Russia and then China, using this chosen theoretical outlook. First, we discuss West Nordic relations with Russia as a traditional power for the region’s affairs, the largest Arctic state, and the resurgent US adversary. Second, we evaluate relations with China, a key US competitor, the second largest economy in the world, and a great power, fostering its capital and presence above and around the Arctic Circle (Kobzeva, Reference Kobzeva2020). With this comparison, we are testing the hypothesis that the patron intervenes in the relationship of the client with another great power if it considers that an encroachment on his own sphere of security. In the conclusion, we determine the pattern of West Nordic relations with Russia and China within the context of the US patronage and evaluate the outcomes for the future practices of the sovereignty of the West Nordic societies. The research involves sources and literature in English, Russian, Chinese, and Scandinavian languages.

Theoretical perspective

The chosen model reflects the relationship between a patron and a client – two states that hold a significant power gap between each other (Doyle, Reference Doyle1986; Huijbens & Alessio, Reference Huijbens and Alessio2015). The model’s value for our research is in its ability to describe three important characteristics of such interaction. The first one is that such relations are built upon mutual strategic concessions. This presets the condition for balancing interests between the two states. A patron provides security coverage, military and economic services, and benefits of access to the market and technologies. In return, a client grants low-cost and legal geostrategic benefits, e.g. by accepting a military base on its own territory. Naturally, the client’s favourable location is one of the key reasons for establishing patronage, as it is for the West Nordic (Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009b).

The second characteristic is subordination that structures such relations. A leading state exercises control over the clients’ political and economic regime. This creates power asymmetry in favour of a patron. Within the model, the patron’s key interest is to observe and inhibit any adversaries’ infringements on the client’s territory. The patron counteracts via routine hostile activities – such as restricting technology transfer or investments. Another approach is the delegitimisation of an enemy state and portraying it as a violator of norms. In such a setup, a patron tends to act out of ideological contemplations rather than pragmatism (Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009a). The adversary state earns a reputation primarily due to the regime systematically opposing the patron’s one. For the Patron-Client model, the enemy is perceived as a threat to, first and foremost, client states, and not immediately to the patron (Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009b). It is natural to expect that the main enemy state for clients and the patron’s key challenger in the global arena should be the same.

In return for patronage, the client is supposed to stay loyal and compliant towards the dominant partner. This usually means a selective approach to partnerships down to renouncing collaboration with the patron’s opponents (Carney, Reference Carney1989; Veenendaal, Reference Veenendaal2017). To maintain the clients’ compliance, the patron can coerce them to shape policies accordingly. This happens via the carrot-and-stick approach, for example, when a patron provides emergency loans and economic help or cuts economic and security spending (Porter, Reference Porter2020; Sylvan & Majeski, Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009b).

The patron’s coercive behaviour was a common pattern in the Cold War bipolarity and unipolarity (Carney, Reference Carney1989; Veenendaal, Reference Veenendaal2017). However, the discussed model permits diversity. Patron-Client relations can be based not on exclusively ideological merging but on economic bargaining as well. Client states are not necessarily weak or peripheral. They are sovereign and join the patron voluntarily. They have room for manoeuvring in dealing with several patrons or even stay disobedient and use their leverage to incite a patron to counter another patron (Doyle, Reference Doyle1986; Kolstø, Reference Kolstø2020; Schenoni & Escude, Reference Schenoni and Escude2016).

Thanks to an evolved liberal world order, small states unprecedentedly became more equal in terms of rights and authority in the international arena. They received the power to voice against or for the great powers (Maass, Reference Maass2017). This observation provoked optimistic discussions on strengthening the role of the small states for their independent position and guiding world politics. For the West Nordic societies, specifically due to their strategic geography and relative economic well-being, it was suggested to take on the role of norm entrepreneurs (Ingebritsen, Reference Ingebritsen, Ingebritsen, Neumann, Gstohl and Beyer2006). The current power balance shift provided more opportunities for clients’ bargaining due to the relative decrease of the patron’s power globally and in view of emerging economic needs.

With no diminishing of the value of discussion about global opportunities for small states, we aim to define more precisely what it means for practice of clients’ sovereignty in the framework of their relations with great powers. With this research requirement, we approach the third characteristic of Patron-Client relations: they are inextricably linked with the issue of sovereign inequality (Donnelly, Reference Donnelly2006). To proceed further, we should elaborate on this core notion of international relations.

The “conventional” understanding of sovereignty counts it as an obligatory criterion of the state, a measure of the state’s freedom towards its citizens and neighbours, and an “ability to act” according to the principle of autonomy (Haslam, Reference Haslam1999). In such an interpretation, sovereignty remains an ideal orientation for international politics (United Nations, 1945). It is considered to be the only fully legitimised institutional form and is taken for granted for all states (Krasner, Reference Krasner2009).

At the same time, the meaning, nature, and interpretation of this phenomenon have been evolving since its early days (Carr, Reference Carr2016). It has ranged from being perceived as a valid criterion of the state’s existence to the legal concept or a power construction that can be changed via discourse (Holsti, Reference Holsti2004; Shadian, Reference Shadian2010). While inclining to the classical definition, we disagree with reducing it to a purely legal interpretation that conforms to a binary rule: either it exists or it does not, with no in-between positions. Instead, we suggest looking at sovereignty as a complicated phenomenon that is divisible by its nature (Adler-Nissen & Gad, Reference Adler-Nissen and Gad2014; Keene, Reference Keene2002).

The prevailing international practice shows that the enjoyment of full-fledged sovereignty is more of an exception and a privilege for the most powerful actors (Carr, Reference Carr2016; Gibbs, Reference Gibbs2010; Schenoni & Escude, Reference Schenoni and Escude2016). For the majority of small or peripheral states, sovereignty takes on various forms with the gradation of its presence, both de jure and de facto. Different types of relations with unequal distribution of sovereignty present cases when particular components of sovereignty are lost in favour of the great power or shared with it, e.g. trusteeship, condominium, colonial possessions, governance assistance, certain types of partnerships, etc. (Keohane, Reference Keohane1984; Krasner, Reference Krasner2009). The Patron-Client relations reflect a similar pattern. The power gap between actors, the requisite client’s compliance to rules set by a major state, and a patron’s involvement in a weaker partner’s security necessitate the deviation of a conventional sovereignty practice (Schenoni & Escude, Reference Schenoni and Escude2016; Waltz, Reference Waltz2010). The gradation here varies from a full patron’s control (as in the case of colonialism) to more flexible or equal relations (as in a condominium over a certain territory) (Rossi, Reference Rossi2017).

The observation of the unequal sovereignty distribution gives a persistent reason for debates and interpretations. One worth noting is the idea of “sharing” sovereignty suggested by S. Krasner. With this term, the author described voluntary relations between states, with one of them usually being badly governed, or failed. Within a framework, a powerful actor takes certain governance responsibilities in exchange for loyalty and other privileges of the patronage. Some of those responsibilities are inextricably linked with sovereignty competencies and practices (Krasner, Reference Krasner2009).

Mainly focusing on examples of peripheral states as well as the US and USSR alliances during the Cold War, S. Krasner notes that sharing sovereignty is a more wide-ranging case in world politics. Even prosperous states may agree to “à la carte sovereignty loss” as in the case of the EU. Though the European states are not failed or badly governed, they have agreed to share certain spheres of sovereign competence with each other (Krasner, Reference Krasner2009; Solon, Reference Solon2013).

The remarkable insight of Krasner’s idea is that such types of relations could become legitimate and conventional if being established by a kind of agreement or contract between states, including great powers (Krasner, Reference Krasner2009). For our research, we pursue this idea further. Namely, if such agreements are thinkable, that would mean the need for defining sovereignty’s components apt for sharing as well as terms and conditions of such interaction. The foregoing approach results in nothing else but customisation of sovereignty, i.e. establishing it as a complex of commodities, able to be shared amid holding internationally recognised legal sovereign status.

Viewing the Patron-Client relations through such a perspective, we can comprehend that they are based on the very specific mutual concession where the client bargains for sharing certain sovereign components in exchange for a set of services provided by a patron. Those services should be exclusive or take a bigger stake in the field compared to any similar service from other countries. In this perspective, patrons and clients are to a certain point, “equalised.” Patrons claim for clients not by “right of the strong” but by offering the best services. In turn, clients are free to set and vindicate boundaries in their relations with the patrons according to their own national interests and not by coercion.

If, as by Krasner, such a type of patronisation could be supported by a legitimate agreement, that could bring to life a new format of power relations, based on an elaborate set of regulations. For the client, that would minimise the omission of their interests happening by default and accordingly restrict the coercion. For the patron, the rules could increase predictability in relations with the adversary state approaching the client, thus raising transparency in international relations. In general, the rules would allow using the advantage of Patron-Client relations’ first characteristic via a more subtle approach to strategic concessions.

This perspective urges a necessity for client states to determine boundaries and ways of sharing security, political, and economic control. Such a reflection could help small states to find their place on the new world map and possible ways for strengthening sovereignty already achieved. As mentioned earlier, one of the promising dimensions is norm entrepreneurship which retains its value despite the preponderant security agenda. These assumptions, we hope, could add momentum to the discussion of sovereignty as a good or a set of commodities grounding the trend to pragmatic international relations amid the power balance shift (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2019).

For the current discussion, we use this theoretical premise. Further, we sequentially ask the following questions: Did we see a decrease or increase in patronage from the US in certain spheres? Does the adversary state offer exclusive services or does the cooperation with it take a major part in certain areas compared to other states? Does the client make noticeable concessions in favour of the adversary power? Is there a clear patron encroachment in West Nordic relations with the adversary state? What does the year 2022 change for the West Nordic sovereignty practices?

West Nordic relations with Russia

The USSR was the US’s key adversary whose every step was overseen or opposed. During that time, the West Nordic states accumulated an outstanding bargaining experience when they managed to keep relations with the enemy state for their own interests (Bertelsen, Reference Bertelsen2020). Unipolarity allowed for more flexible cooperation with Russia. The substantial advance occurred in two dimensions, the Arctic and fishing, which inherited the fruits of diplomatic interaction with the USSR (Greunz & Ward, Reference Greunz and Ward2017).

For Russia, relations with West Nordic states fall into the scope of Arctic affairs. The Russian Arctic strategy builds around the idea of international cooperation in the Northern Sea Route development. The West Nordic states are considered potential contributors to it (The Official Internet Portal of Legal Information, 2020). Nevertheless, due to socio-economic issues and political discord with European partners, Russian presence in all three states was imperceptible even before 2022.

The US regarded Russia’s development of its military capabilities and infrastructure in its High North as a security challenge (Boulègue, Reference Boulègue2019; Krog, Reference Krog2020; Sergunin & Konyshev, Reference Sergunin and Konyshev2016). After Russian military actions in Ukraine in 2022, the security juncture for the region changed. The new NATO strategy called Russia a threat to the alliance states (NATO, 2022b). The West Nordic territories are able to fill the gaps in the US and NATO security, both with new military installations and data surveillance exchange (Forsvarsministeriet, 2021). The Cold Response 2022 manoeuvres demonstrated the alertness of allies including the West Nordic to operate in the High North (NATO, 2022a). On the bilateral level, political rivalry changed the West Nordic abstinent approach to Russian policies outside the region. Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland have condemned Russia’s behaviour and launched various sanctions on it. In response, Moscow published a list of retaliatory sanctions for several public figures (TASS, 2022).

Iceland-Russia relations

The USSR was a great power able and willing to advertise alternative services to the West Nordic small states: both ideological, economic, and for security. Nevertheless, the USSR could not reasonably plan to gain a foothold in the heart of NATO. Moscow was interested foremostly in having an exchange in kind and was ready to provide exclusive terms when Icelandic seafood and wool were traded for Soviet vehicles, machines, and fuel (Embassy of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Iceland, 2010). Moscow also provided support in Iceland’s Cod Wars with Britain (Bragason, Reference Bragason2018).

Iceland’s cooperation with the USSR was always decried by its patron and its allies holding a narrative of a naïve society that would pay too dearly for its credulity. The adversary state, in line with the logic of the Patron-Client model, was considered in the US as a threat primarily to the West Nordic society. However, for Iceland, there was no doubt about choosing the “right” patron. The key aspiration was in using its economic ties with the Soviet Union for balancing its relations with the US (Olmsted, Reference Olmsted1958). The Communist Party in Iceland was one of the key platforms for cooperation with the Russian communists, yet keeping an independent line from the Soviets (Gilberg, Reference Gilberg1975).

The current dynamics occur due to the new power balance shift and the temporary decrease in services provided by the traditional patron. The pivotal time for Icelandic politics happened in 2008 when amid the global financial crisis and the Icesave dispute, the US and the EU were not willing to offer financial support (Bergmann, Reference Bergmann2016). To accommodate their needs, Iceland turned to alternatives, including Russia. Moscow refused to provide the swap despite speculations that in turn, she would ask to use the former US airbase in Keflavík for refuelling (Leira & de Carvalho, Reference Leira and de Carvalho2016b; Rozhnov, Reference Rozhnov2008). Due to internal economic troubles and reluctance to increase the political burden, Russia had no capacity to offer exclusive services to the West Nordic state in any field. It also walked out on ideological rivalry in the Cold War times. Its cultural influences in Iceland were narrowed to reconnecting its diaspora or commemorating Polar Convoys arranged via Icelandic ports – both of a marginal effect on local society (Curanović, Reference Curanović2012; Lange-Ionatamišvili, Reference Lange-Ionatamišvili2018; Patriarchia.ru, 2020).

It is fair to say that after the political reboot in the 90s, Iceland-Russia cooperation became more diverse and included science, tourism, the labour market, Arctic affairs, and geothermal energy (Iceland Review, 2011). However, bilateral trade remained insignificant, and since 2014, calculations showed a remarkable drop in trade (Iceland Chamber of Commerce, 2021). As of 2019, Iceland was 94th for Russia, and Russia was number 124th for Iceland in the marketplace (Reykjavik Economics, 2016; russian-trade.com, 2020).

Iceland was putting efforts into pertaining its place in the Russian fish market amid sanctions after 2014. This small state with a narrow economic focus is in constant need of diversifying trade, which opens the way for pragmatic bargaining (Thorhallsson & Gunnarsson, Reference Thorhallsson and Gunnarsson2017). In 2019, Iceland established the bilateral Chamber of Commerce with the hope of developing trade in the future (Iceland Review, 2019). As of August 2022, its webpage is unavailable.

To sum up, before 2022, Iceland-Russia cooperation was running in a conventional manner. Russia’s languid approach did not provide a reason for a patron’s involvement and did not affect the practices of the sovereignty of the West Nordic state. Currently, Russia’s role as a NATO adversary and a threat nullifies the chance for positive advancement in cooperation (Wilson Center, 2022).

The Faroe Islands’ relations with Russia

Faroese relations with Russia resemble the Icelandic ones, yet with a more contrasting dynamic. In Soviet times, Moscow was even less ready to advertise itself as an alternative patron to an actor located at the heart of the Western block. Moscow’s actual interest was in acquiring minimal loyalty to conduct legitimised fishing. Another hope was to prevent the establishment of military bases of the hostile camp there via trust-building, which happened all the same. Faroese, in turn, was further from its dreams of sovereignty compared to nowadays. The only sphere for bargaining was regarding fishing quotas, which do not hold much ground for unilateral benefit. Nevertheless, it raised sceptical sentiments in Copenhagen regarding possible propaganda intervention towards Faroe Islands’ society perceived as naïve and vulnerable (Jensen, Reference Jensen2004). After the dissolution of the USSR, most of the connections were lost and Faroe Islands’ value for US security waned (Bertelsen, Reference Bertelsen and Zellen2013).

The shift for the Faroes happened to be more turbulent than for Iceland. The first reason for that was the dynamic political drift towards independence from the Danish Realm. It created an incentive towards self-sufficing governance and the setting of foreign policy priorities. The second factor is the predominant power of the fishing industry amid moderate capacities in other spheres. The third impetus happened due to the EU sanctions towards Faroese seafood that drove a wedge in relations with the EU and forced the archipelago to diversify its market. The above provided a reason for a period when the initiative in relations with the patron’s former adversary was taken up by the fishing industry.

The Faroe Islands did not join sanctions on Russia in 2014, thus avoiding countersanctions, and started the active promotion of its business in Russia. In 2015, the Government established a Representative Office in Moscow (the office is not available online in August 2022). The Faroese Government also signed a memorandum of understanding with the Eurasian Economic Commission, the regulatory body of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). A Free Trade Agreement with the EAEU was under consideration (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2019).

In the Faroe Islands, perceptions towards trading with Russia were rather positive (Skorini, Reference Skorini2022). The two states exchanged significant fishing quotas (Fiskiveiðiavtalur, 2019). Faroese business and diplomatic leaders visited Russian fisheries regions to discuss plans for wood and fish processing (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2018). The above dynamic also inspired the rise of scientific and people-to-people ties. With such steps, the Faroe Islands became a fish exporter to Russia with a stake of the market share of 32.8% of the total in spite of its higher price compared to Norwegian supplies (Matzen & Gronholt-Pedersen, Reference Matzen and Gronholt-Pedersen2018). The Faroe Islands were tardy in imposing sanctions and designed them not to affect the important fish trade and fish stock exchange (Nolsøe, Reference Nolsøe2022). In 2022, Russia is still counted as the largest importer of Faroese fish (ibid.). Yet, amid the aggravating relations with the US and NATO, Russia can lose the progress achieved so far.

Moscow’s passive position in relations with the archipelago had not triggered the patron’s direct involvement up until 2022. The only discrepancies had arisen with Denmark regarding air area violations. They were tuning the Faroese attitudes in line with the patron’s security concerns. Two Faroese political parties were promoting new radar installations on the Islands and the fast entry into the EU to strengthen their ties with the NATO block (Mouritzen, Reference Mouritzen2020). Those moves had been perceived with scepticism by other Faroese politicians who voiced opposition to entering the great powers’ game as an object (Lomholt, Reference Lomholt2022). In 2022, the construction was confirmed (Forsvarsministeriet, 2022). This decision reinforces relations with the patron as a security guarantor and obstructs further cooperation with Russia. For the Faroe Islands, this would likely mean the demise of any opportunity for bargaining with other alternative powers, including China.

Greenland-Russia relations

Since the Cold War, the critical importance of Greenland’s minerals, sea passages, meteorological, and space awareness infrastructure placed it in the US security domain. This determined relations with the key patron’s adversary. The only successful cooperation with the USSR was regarding fishing quota exchanges. Any Soviet involvement was scrutinised for its potential to sow dissension in Greenlandic society, which was depicted as vulnerable and naïve (Sørensen, Reference Sørensen1979). Moscow had no capacity to advertise its patronage over the area.

Today, Greenland is moving towards its sovereign status and its foreign policy perspective in many ways follows cues from other West Nordic neighbours. Like the Faroe Islands, Greenland did not support anti-Russian sanctions in 2014 to allow its fish trade to increase. Nevertheless, it supplied only 2% of all fish exported to Russia (SeaNews, 2020). Greenland put efforts into developing fishing quotas exchanges. Countries elaborated sustainable interaction mechanisms based on sharing scientific knowledge (Government of Greenland, 2020). However, in most cases, cooperation with Russia went through Copenhagen as a third party and did not reach remarkable progress in other areas (EmbassyPages.com, 2021; Leira & de Carvalho, Reference Leira and de Carvalho2016a). In 2022, Greenlandic companies had to stop trade with Russia due to accounting problems as the Russian bank system was sanctioned (Sermitsiaq.AG, 2022).

The reason behind such reluctant cooperation is Greenland’s embeddedness in US security. Thule Air force Base with radar facilities remains crucial for the US’ early warning system, missile defence, and space surveillance. The Russian refurbished Nagurskoye airbase facing Greenland triggered a security dilemma (Kramnik, Reference Kramnik2020; Rumer et al., Reference Rumer, Sokolski and Stronski2021). Thus, long after the Cold War, Greenland-Russia bilateral relations are tuned by strategic deterrence, which has little in common with the local Nuuk political agenda.

The new great power rivalry wave disrupts future cooperation with Russia. The Danish authorities’ commitment to take every precaution possible to ensure its security dominance in line with US interests plays a decisive role (Svendsen & Skov, Reference Svendsen and Skov2019). More surveillance and possibly radars in Greenland are being promoted as providing climate awareness and employment in addition to security (Forsvarsministeriet, 2021). Further American and Denmark funding for defence and surveillance on Greenland will cement Nuuk’s subordinate status in Patron-Client relations (U.S. Embassy & Consulate in the Kingdom of Denmark, 2021). However, the reason for the above comes not only because of Russian strategic forces but also from China’s involvement in Greenland.

Case 2: West Nordic relations with China

West Nordic ties with China during the Cold War were extremely weak compared to those with the Soviet regime. Recently, by contrast, they have gained more capacity. The Asian country is engaging in most parts of the world that are worthwhile for both their location and resources. As a non-Arctic state, China has no capacity to move into the military sphere in the Arctic or North Atlantic. However, China’s economic capital has been expanding worldwide, including in Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands in all civilian spheres from trade, and tourism, to science and technologies (Jørgensen & Bertelsen, Reference Jørgensen and Bertelsen2020; Kobzeva, Reference Kobzeva2019). China has proposed the construction of the Polar Silk Road in the Arctic, a branch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), opened to the West Nordic states (Xinhua News Agency, 2021). The strong interest of China to develop new sea routes and to become an independent “major Arctic stakeholder” has made the West Nordic states important partners in its Arctic policy (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2018).

The stumbling block for China’s activities in the West Nordic appeared due to its relations with the US. China earned the title of the US’ key competitor, including in the Arctic (United States Department of State, 2019). In 2022, this approach extended with the new NATO strategy that defined China as a challenge for the block that includes the West Nordic by default (NATO, 2022b). In addition, the protracted COVID pause in the Asian country acts as a brake for developing any international affairs, including in the Arctic and the West Nordic region.

Iceland-China relations

Iceland is the only one of three West Nordic societies, which has a recognised sovereignty status. It also has the most extensive relations with China. By and large, Iceland-China relations present the brightest case for our theoretical approach.

The reasons for building up relations with Beijing derive from the diminishing role of the patron in Iceland’s destiny. In 2006, the US withdrew from the Keflavík base due to the decrease in tensions with Russia as a traditional adversary in the West Nordic (the US use of the base is reactivated now). With the lack of any security threat, less attention was thrown to that small democratic society. This security shift preceded the financial crisis in 2008. Iceland’s relief came not from the US or allies, but from China, which contributed a currency swap transaction of 3.5 billion yuan (0,45 billion EUR) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2020b). The offer instantly created a good impression of Beijing’s reliability.

Iceland renewed an aspiration to diversify ties which was supported by a no less energetic Chinese business community. Since the 1990s, Iceland and China have created 12 trade commissions and a series of joint statements, including the Free Trade Zone (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2020b). Chinese investments are presented or were involved in key Iceland hi-tech areas, such as mining, and exploration of resources, including hydrocarbons and minerals (China Petrochemical News Network, 2014; Over the Circle, 2018). Iceland and China maintain scientific collaboration with high-level political support. The brightest cases include the «Xue Long» icebreaker’s visit to Reykjavík in 2012 and the establishment of the Joint China-Iceland Arctic Observatory (Chinese Embassy in Iceland, 2012). In other words, the list of China’s services was not limited by the occasional financial injection. It was replenished by wide economic opportunities, which the US was not ready to provide, and crowned by the invitation to the Belt and Road Initiative. Iceland is considering the latter in spite of US opposition (Lanteigne, Reference Lanteigne2017; The American Presidency Project, 2019).

The Icelandic side made salient concessions in return. Icelandic politics are tolerant to the point of being ready to foster dialogue with the Chinese communist party, China’s ritual voice in any negotiations (Liu, Reference Liu2020). In addition to a chance to participate in Arctic development, the West Nordic state granted China the opportunity to speak in front of an international audience. The Arctic Circle Assembly, organised by then-president of Iceland, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, is an important West-oriented platform for China amid having no voice in the Arctic Council (Hallsson, Reference Hallsson2019). For this reason, in some Chinese experts’ extreme evaluations, Iceland was discussed as a probable base to oppose the dominance of Arctic major coastal states, including Russia, the US and Canada, in decision-making for the region (Qian & Zhu, Reference Qian and Zhu2015).

The US was expressing relentless opposition towards China-Icelandic cooperation. However, there was no event that met with the same anxiety as China’s attempt to buy land. The deal that urged the patron’s intervention is related to the Zhongkun Group’s initiative to buy a 0,3% area of Icelandic territory for an elite resort. The idea of 100 hotel apartments seemed reasonable due to the influx of Chinese tourists. Icelandic partners considered it an attractive offer and some scholars still tend to see the deal as a purely economic one (Einarsson et al., Reference Einarsson, Hannibalsson and Bailes2014). Local concerns appeared due to the Zhongkun group’s financial and operational opacity to the extent that doubts were entertained as to the existence of the company (Huijbens & Alessio, Reference Huijbens and Alessio2015). However, the case was discussed not as a threat but as one more argument for elaborating legal regulation of foreign investments and the right of foreigners to own land (Nielsson & Hauksdottir, Reference Nielsson and Hauksdottir2020).

The patron’s perception was of another kind. The key arguments were about the relative proximity to the Finnafjord with a future deep seaport and the possibility of a constant Chinese presence in Iceland. Against this backdrop, the US and Canadian military circles sounded a note of warning about the potential threat to Iceland’s security and territorial integrity. The undertone put a spin on Icelanders as naïve partners in terms of security maintenance. As a result, the purchase was rejected with great resonance in the media and gave ground to refusing any similar project in Scandinavia (Foley, Reference Foley, Kristensen and Rahbek-Clemmensen2017). It also contributed to the alarmist expert discourse on China’s historical revenge for the Opium Wars – attempts to obtain the right of concessions abroad following the Western states’ destructive example (Huijbens & Alessio, Reference Huijbens and Alessio2015). In such a view, China and its initiatives are being easily labelled suspicious and illegitimate.

In 2022, the two countries’ mutual intentions remain plainly pragmatic. Amid the global pandemic and political disregard between the great powers, Iceland and China have proceeded with bilateral trade and cooperation (Farrell, Reference Farrell2022; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). However, further, the development will likely follow the global rivalry trends.

The Faroe Islands’ relations with China

The Faroese turbulent context described earlier turned purely business relations into high politics. As in Iceland, the Faroe Islands’ cooperation with China was due to an active position from local entrepreneurs and government. Relations have not experienced a long history but gained momentum a while ago due to changes in the fish market juncture. The Faroe Islands availed of the opportunity when Norwegian salmon was blocked for political discrepancies with Beijing in 2010. Thus, the Faroe Islands entered the Chinese market and took the lead as a key chilled salmon exporter to China. Currently, Norway tops the list, but the Faroese business community holds a position as one of the key exporters. It also established its first representative office in Beijing (NetEase Inc., 2020).

The cooperation helped to attract Chinese businesses capable of providing groundbreaking high technologies service. The latter became a wake-up call for Washington. The close to be successful deal of Huawei on 5G for the Faroe Islands became a vibrant case of patron intervention. The US was loud in opposition to the deal. Washington defined the Huawei 5G deal as a threat to the security and democratic values of the Faroe Islands, Denmark, and the NATO alliance (Lairson et al., Reference Lairson, Skidmore and Wu2020). The US ambassador in Denmark, Carla Sands, alarmed the Faroese public over the security threat of the Huawei 5G network and accused Kenneth Fredriksen, the Scandinavian branch director of Huawei, of working for the Chinese Communist Party (Hecklen, Reference Hecklen2019).

The counter-reaction was hard to conceal. The unexpectedly leaked dialogue between the Chinese ambassador to Denmark and Faroes government officials revealed the true assertiveness of China to support the company and gave allusions to the discussion about the Free Trade Agreement behind closed doors (Kruse & Winther, Reference Kruse and Winther2019). In the light of this leakage, China was trying to push against the suppression. The spokesperson for China, Hua Chunying, worded her indignation in the phrase: “The era when China cannot talk back has gone” (guancha.cn, 2019). The Faroe Islands’ attitude was also not like Denmark’s. The dictatorial tone of Washington and Copenhagen bypassing the local decision-making levels was interpreted as Denmark’s attempt to limit the Faroe Islands’ independence by covering it up as a security issue (Bertelsen & Justinussen, Reference Bertelsen and Justinussen2020). Our research perspective rather proves this concern – no matter if the security issue was or was not true.

The Huawei debacle reflected the US’ decision to deter China in the West Nordic region. The US adopted an explicitly more active attitude and decided to go back to its client. The US stepped up developing ties with the Faroe Islands, both socio-economic and military ones such as obtaining improved port access and promoting guided-missile destroyer refuelling at the Faroe Islands (Grosvenor, Reference Grosvenor2019; Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2020; U.S. Sixth Fleet Public Affairs, 2021). In addition, Washington bolstered teaming up with Denmark by praising Copenhagen’s $240 million investment in “domain awareness” including in Greenland and the Faroe Islands (United States Department of State, 2021).

In a broader perspective, the case highlighted a strong regime deficiency: the lack of international rules, regulations, and mechanisms of cooperation in advanced technologies. Amid no universal regulator system, the case of technological transfer inevitably falls into either of the patrons’ judgement, while the client faces the uncompromising choice of being pro or contra. At the same time, we assume that for small societies, this moment is not just a political challenge. The regulatory gap requires new norms and standards. The small states’ initiatives here could be favourable for setting terms for balancing their interests in relations with great powers.

Greenland-China relations

The Greenlandic case holds similar initial conditions as the Faroe Islands one: the move towards sovereign status and decreased patron’s services. The latter inter alia leads to reduced valuable contracts for Thule Airbase services partially provided by Greenlandic companies (Sermitsiaq.AG, 2015). Against this background, Greenland was observing the Faroe Islands and Iceland’s successful Chinese market entry and the advantages of the Icelandic fish industry owing to the Free Trade Agreement. When the country had not received support from the US or the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenland adopted a welcoming stance to foreign investments to bargain for better independence (Grydehøy et al., Reference Grydehøy, Bevacqua, Chibana, Nadarajah, Simonsen, Su, Wright and Davis2021).

The cooperation with China was at first developed in the framework of Sino-Danish relations seen as a comprehensive strategic partnership. In the recent decade, relations have turned into a bilateral format (Sørensen, Reference Sørensen2018; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2020a). China became Greenland’s second largest import seafood market (Royal Greenland A/S, 2019). China was also supposed to be a significant investor in mining. In 2021, Nuuk opened its first representative office in Beijing to coordinate cooperation with China, Japan, and South Korea (Lindstrøm, Reference Lindstrøm2021).

In return for cooperation, Greenland made moderate diplomatic concessions to China. Namely, Nuuk withheld its support of Tibetans as an indigenous culture colonised by a great power – the position they upheld in the 1990s (Jacobsen & Gad, Reference Jacobsen, Gad, Kristensen and Rahbek-Clemmensen2017). At the same time, Greenland acted with discretion and considered improving the regulations for mineral exploration. In 2015, Greenland and China prepared a Memorandum of Understanding for cooperation in the field, which has not yet been signed in the aftermath of political discord (Government of Greenland, 2015).

For China, business ties with Greenland became a part of Arctic politics and potentially could contribute to the Belt and Road Initiative. China had the capacity to provide significant economic and technological services to Greenland but was initially hesitant in making investments. Its involvement in exploration happened due to the active recruitment by British and Australian companies (Foley, Reference Foley, Kristensen and Rahbek-Clemmensen2017). Nevertheless, China’s engagement provoked patron involvement. The key reason is the great value of Greenlandic resources and geography for the US. Thus, for the patron, China’s engagement in Greenland business is perceived as an encroachment into their strategic domain.

The first sensitive area is Greenland minerals – primarily rare-earth elements (REE). China’s global dominance in REE market remains a matter of concern for the US as well as the EU (Dreyer, Reference Dreyer2020). In addition, for Denmark, this also created apprehension about further decoupling with Greenland establishing partnerships abroad (Lanteigne & Shi, Reference Lanteigne and Shi2019; Wu & Shui, Reference Wu and Shui2017). Within the framework, Denmark acted as a junior patron and defined China’s activities as a threat. Danish politicians argued that raising dependence on Chinese capital will question Greenland’s independence, and the invasion of Chinese labour will cause the loss of Greenlandic identity amid this foreign cultural pressure (Gad et al., Reference Gad, Graugaard, Holgersen, Jacobsen, Lave and Schriver2018). This is even in spite of the planned reduction of Chinese workers from 45% to zero after educating local employees (Foley, Reference Foley, Kristensen and Rahbek-Clemmensen2017). This is concurrent with a patron’s practice to picture an adversary as an existential threat to a client.

The decision was made due to local reasons. The democratic socialist separatist Inuit Ataqatigiit party, which won elections in 2021, blocked the extraction and exploration of oil and gas in Kvanefjeld due to environmental concerns (Government of Greenland, 2021). Less critical for the US, the project on iron ore in Isua, remained on hold, in spite of the Greenlandic debates on labour and immigration policies (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2012). In 2021, the Chinese licence for it was withdrawn as well (Reuters, 2021). Currently, the future of Chinese investments in Greenland has lost its promise despite recent studies arguing for the lack of financial threats to Greenland from such cooperation (Schøler & Lanteigne, Reference Schøler and Lanteigne2022). Amid global rivalry, the issue of resource accessibility and control is a priority for great powers’ decision-making.

The second area encompasses projects that potentially affect the patron’s security dominance. They include the Chinese idea of launching a satellite ground station for polar research, the General Nice (Chinese company) proposition to buy an abandoned naval base in Grønnedal, and the interest of Chinese investors in developing Greenlandic airport infrastructure (Lulu, Reference Lulu2017). All these projects were welcomed by the Greenlandic side and blocked by Copenhagen amid strong concern expressed by Washington. The US and Denmark presented Chinese initiatives as potentially a dual-use threat and a question of Greenland’s ability to keep its identity and independence. The latter, again, evocates a persistent image of Greenlanders since colonial times as naïve natives who could be easily cheated (Grydehøy et al., Reference Grydehøy, Bevacqua, Chibana, Nadarajah, Simonsen, Su, Wright and Davis2021; Kristensen & Rahbek-Clemmensen, Reference Kristensen, Rahbek-Clemmensen, Kristensen and Rahbek-Clemmensen2017).

Subsequently, the US and Denmark made a series of steps to increase the patronage and abolish opportunities for China to grow in the same areas. The US intensified collaboration with Greenland on resource development, opened a consulate in Nuuk, and increased investments in the economy and education (Government of Greenland, 2019). The Danish parliament decided to urgently restore the disused base and increased investments including in security domain awareness (Matzen & Daly, Reference Matzen and Daly2018). Currently, the mere fact of Chinese presence in Greenland gives cause for alarmism and any business proposition from Beijing is likely to be complicated or banned (Lanteigne & Shi, Reference Lanteigne and Shi2019).

As an apogee, Trump’s idea to buy the island, publicly advocated on Twitter, acutely revived the issue of colonial practices. From our perspective, such an inconceivable deal would undermine Greenland’s progress towards sovereignty sharper than Nuuk’s attempt to involve investors from the PRC. For our discussion, it is worth highlighting not the US President’s tweet, but the trend observed. As we elaborated above, the patronage over Greenland could take various degrees of influence depending on how the sovereignty will be customised and then shared between the actors. From such a perspective, the more worrisome fact is that the US does not leave its client much space for bargaining with outsiders. The patron also does not seek for presetting the conditions for cooperation with the opponent via developing universally applicable regulations. Such a dynamic will likely lead to coercive shutting down of the patron’s domain for any cooperation with the adversary state, thus narrowing the scope for the client’s acquisition of genuine sovereignty.

Conclusion

The suggested theoretical outlook elaborates on the Patron-Client model in reference to the current power balance shift and changing practices of sovereignty among West Nordic societies. The shift showed itself in the patron’s (the US’s) episode of decreased services in the West Nordic region during unipolarity when no immediate adversary state was observed. Clients (Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland) experienced the need to bargain with other influential actors for their own national interests while strengthening or reaching for sovereign status. The eased patron’s control allowed a flexible client approach to cooperation. In the West Nordic region, Iceland showed the brightest example of bargaining with several great powers. Its behaviour serves as a valuable model for the Faroe Islands and Greenland that aspire for sovereign status.

The rising of opponents changed the patron’s behaviour. China and Russia are clearly named as the main adversaries of the US and NATO. In recent years, the US increased its patronage over the West Nordic. With the last drop in the Ukraine conflict, the US turned from being a fade-out patron to an uncontested one. The client states are valued again for their role in the patron’s security, both due to geography and strategic resources. Any clients’ alternative behaviour is condemned, and their economic losses resulting from the disrupted relations with the adversary are perceived as an obligation and not a substantial problem. Instead, new military developments in the area are discussed as a contribution to local economics.

The above mentioned juncture sharpens the issue of power and sovereign inequality between patrons and clients. It also raises the question of the future legitimate sharing of sovereignty between them – either primarily on the patron’s terms or with due consideration to the client’s interests. In this regard, we point at the earlier overlooked corollary of such a development – the customisation of sovereignty and comprehension of it as a set of commodities that clients and patrons may share, or different patrons may compete for. Such a perspective outlines the need for the West Nordic small societies to consider terms and rules of further relations with the patron state and other great powers to ensure sovereignty both de jure and de facto.

The dominant security agenda suppresses initiatives in other areas stating them as less critical. This constricts opportunities for small partners to act. The agenda also fastens the narrative of small societies’ “naïvety,” since, amid the new challenges, clients’ need for patronage seems self-evident. In such circumstances, anchoring the West Nordic achievements in the international arena requires special effort. Possible leverages arise in norm entrepreneurship and regime-making. The existing scope of rules and regulations do not ensure safe cooperation in areas related to security such as technology and scientific cooperation with dual-use capacities. Elaborated regulations could help small powers defend their interests against adversary states and the patron who determines security policies. Another dimension is in launching viable negotiating platforms focused on the Arctic. A more dispersed state of High North affairs that will likely occur due to the pause of the Arctic Council and other fora sharpens the need for such initiatives. All the great powers remain interested in the dialogue. The three West Nordic societies avail substantial experience in pursuing pragmatic cooperation related to the Arctic. In this regard, an enterprising approach can provide the three societies with better opportunities for more balanced interaction with the great powers.

Russia and China lost the opportunity to be considered as alternative patrons and acquired the role of adversary states, both for the US and for its clients. In the case of Russian affairs with the West Nordic, the patron’s opposition remained weak until 2022. US behaviour reiterated certain patterns of the Cold War. The controversy went via Denmark and regarded security issues often far from the West Nordic states’ competencies. Russia remained passive in relations with the three societies. It did not suggest services to bargain for and did not become a unique partner to any of them. The military actions in Ukraine in 2022 largely eliminated opportunities to advance cooperation, while business and political achievements will likely be discarded. Amid no local grounds to threaten West Nordic societies, Russia is considered to be the main security challenger to the region in accordance with its ongoing rivalry with the US.

Another adversary state, China, showed the potential to become a patron of the region. China provided salient economic, financial, and technological services and had ambitions to involve the three island nations in the Belt and Road Initiative. In return, the West Nordic states afforded small symbolic concessions valuable to China. In line with the chosen theoretical model, it provoked a sharp patron reaction. The US countered projects and tried to delegitimise China picturing it as a violator of norms in the Arctic, in high technologies, and globally. Today, China’s solid strategic partnership with Russia, increasingly obstructs Beijing’s future affairs in the West Nordic, including the plans for implementing the Polar Silk Road initiative.

In the West Nordic, the US-China countering behaviour is developing asymmetrically. If the US and USSR were mainly competing in ideology and security areas, China focuses on economic development. Beijing remains facile to the small states’ cooperation with the patron in the security domain and places stakes on resources and new routes development. China attempts not to replace but to complement the US. In such a perspective, the US could respond by providing better services to clients via economic help or investments to replace the rival. However, the observation is that the US is not going to tolerate opponents, the same as it was in the Cold War. Being absorbed in the security build-up, the US presses clients to choose a side and is encouraging building up ideological discrepancies. Such behaviour solidifies patronage over the West Nordic and challenges their pathways to reach viable sovereignty.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224742200033X

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to all discussants of the paper for their critical comments and suggestions. The initial versions of this paper were presented during the conference “Greenland-Denmark 1721-2021” and the XIX Nordic Political Science Congress 2021. Special appreciation to anonymous reviewers.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.