1 Introduction

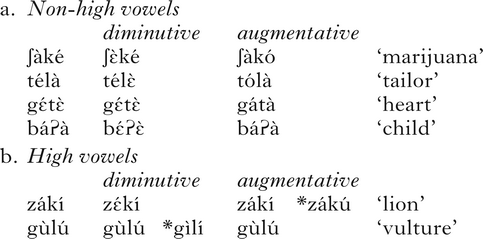

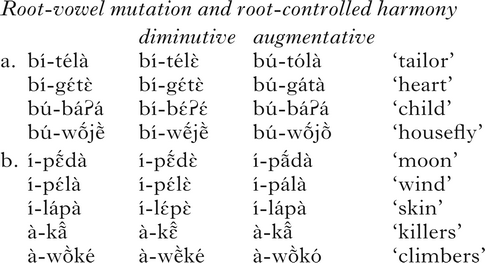

This paper investigates a pattern of root-vowel mutation in Fungwa (Kainji), an endangered language spoken in Nigeria (Akinbo Reference Akinbo2021). In the language, non-high vowels of nominal roots are fronted to mark the diminutive (e.g. smallness), as in (1a). To mark the augmentative (e.g. bigness), the non-high vowels of nominal roots are backed. When all the root vowels are non-high, the mutations result in root-internal vowel harmony. As shown in (1b), under the same condition as the non-high vowels, high vowels are invariant. Diminutive and augmentative are categories of evaluative morphology, which involves linguistic objects that express concepts such as quantity (e.g. small vs. big), quality (e.g. good vs. bad) and affection (e.g. neutral, positive or negative) (Déchaine et al. Reference Déchaine, Girard, Mudzingwa and Wiltschko2014). Prior to my original fieldwork on the language, this pattern of mutation had not been reported for Fungwa, nor, to a large extent, for other Kainji languages.

-

(1)

My underlying assumption is that root-vowel fronting and backing are the result of featural affixation (see Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1996). In Fungwa, the featural affixes are a diminutive morpheme with a [―back] feature and an augmentative morpheme with a [+back] feature as their phonetic exponents. The realisation of the featural affixes on the root morpheme causes the root-vowel mutations. Given that non-high vowels are cross-linguistically more sonorous than high vowels (Parker Reference Parker2002), I will argue that the high vowels do not undergo the mutations because the root-vowel mutations in Fungwa are prominence-based. The formal account of featural affixation will be based on a featural correspondence account of morphemic harmony (Finley Reference Finley2009) and a prominence-based licensing condition (Walker Reference Walker2005, Reference Walker2011).

This work is of interest for four main theoretical reasons. First, the expression of smallness with fronting and bigness with backing in Fungwa is consistent with sound-size symbolic association in various languages (see Körtvélyessy & Stekauer Reference Körtvélyessy and Stekauer2011). Phonological patterns like those of diminutive and augmentative formation in Fungwa exhibit non-arbitrary relations between sound and meaning, challenging the persistent view that the relation between the form of a word and the meaning is arbitrary (Hockett Reference Hockett1960, de Saussure Reference Saussure1974). Most of the evidence for sound symbolism is from infant-directed speech (e.g. Laing et al. Reference Laing, Vihman and Keren-Portnoy2017, Perry et al. Reference Perry, Perlman, Winter, Massaro and Lupyan2018), probabilistic tendencies in the lexicon (e.g. Ultan Reference Ultan, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978, Bauer Reference Bauer1996, Gregová et al. Reference Gregová, Körtvélyessy and Zimmermann2010, Körtvélyessy & Stekauer Reference Körtvélyessy and Stekauer2011) and psycholinguistic experiments (e.g. Sapir Reference Sapir1929, Ramachandran & Hubbard Reference Ramachandran and Hubbard2001, Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Schuerman, Reinisch, Tufvesson and Mitterer2016), but Fungwa presents natural, categorical and deterministic evidence for sound-size symbolism. The second area of theoretical interest is phonological asymmetry, which involves assigning privilege to some segments or word positions over others. Cross-linguistic evidence for asymmetry abounds in arbitrary phonological patterns (Zoll Reference Zoll and McCarthy2004, Walker Reference Walker2005, Reference Walker2011), but most, if not all, evidence for asymmetry in non-arbitrary phonological patterns comes from lexical probabilistic tendencies and experimental conditions. The preference for non-high vowels over high vowels in the realisation of the featural affixation in Fungwa is a kind of asymmetry in sound symbolism. The third area of interest is phonetic and psycholinguistic prominence, which is a recurrent issue in phonological asymmetry. A variety of studies have shown that privilege is assigned to phonological elements with phonetic or psycholinguistic prominence (Beckman Reference Beckman1998, Zoll Reference Zoll and McCarthy2004). In line with findings of previous research, I argue that the asymmetry in the realisation of the featural affixes is motivated by the phonetic prominence of non-high vowels. The prominence-based realisation of the featural affixes is intertwined with the fourth area of interest, phonetic naturalness. Just as in arbitrary phonological patterns, I will argue that the sound-size symbolism of the featural affixes is also phonetically grounded.

As background to the discussion, the sound inventory and the relevant aspects of Fungwa phonology and morphology are presented in §2. In §3, I present a basic description of the root-vowel mutations. An analysis of the root-vowel mutation is presented in §4. The alternation of the vowel [ɛ] with [a], instead of [ɔ], in the root-vowel mutation is accounted for in §5. In §6, the root-vowel mutation is compared to patterns of sound symbolism across languages. The theoretical implications of featural affixation are discussed in §7. A summary and conclusion are presented in §8.

2 Background

Fungwa is a Kainji (Benue-Congo) language with about 1000 speakers (Blench Reference Blench and Watters2018, Eberhard et al. Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2019). The language is spoken in at least thirteen villages along Pandogari-Alawa Road in Rafi Local Government, Niger State, Nigeria. Like most Kainji languages, Fungwa is endangered and understudied (McGill Reference McGill2007, Reference McGill2009, Smith Reference Smith2007). The present paper is based on fieldwork data, elicited in Nigeria from native speakers of Fungwa between 2015 and 2018. The subset of the fieldwork data that forms the basis of this work contains more than 1300 nouns.Footnote 1 As a background to featural affixation, I focus here on aspects of Fungwa morphophonology.

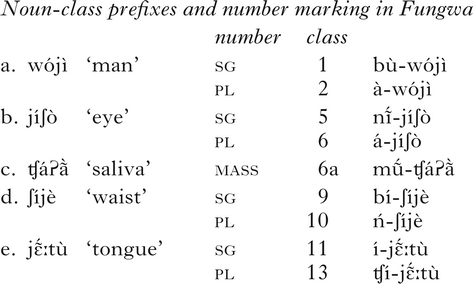

2.1 Noun-class prefixes: number marking

Fungwa has nine noun-class prefixes, which can be grouped into five sets based on their pairing in number marking. The noun-class prefixes interact with featural affixation; this section presents a basic description of the prefixes. The numbering of the noun-class prefixes is based on the system in (2), proposed in work on Proto-Kainji, Proto-Benue-Congo and other Kainji languages (Gerhardt Reference Gerhardt1989, Williamson Reference Williamson1989). Nouns can occur without number marking. An unmarked noun can have singular and plural interpretations, but it can optionally be marked with a noun-class prefix indicating singular, plural or mass.

-

(2)

When a noun is marked for singular, plural or mass with a class prefix, the prefix determines the number interpretation. Phonologically, a noun-class prefix can have the shape CV, V or N. The CV prefixes have front and back variants, with the back variant occurring before a root-initial syllable with a back vowel and the front variant before a root-initial syllable with a front vowel. This alternation is discussed in §2.3. CV prefixes contain only the vowels [i u], and V prefixes are either [i] or [a]. Among other aspects of Fungwa morphosyntax, the agreement markers of noun classes are not discussed, as they have no direct impact on the main focus of this work.

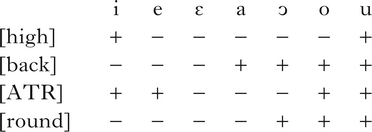

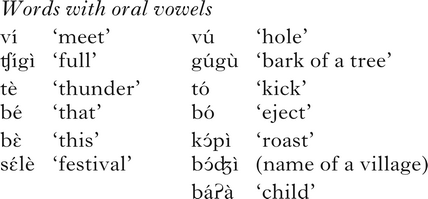

2.2 Basic vowel inventory

The vowel inventory of Fungwa contains seven oral vowels, which are presented in (3) with the relevant distinctive features. Based on its phonetic properties and its behaviour in vowel harmony, [a] is grouped with the back vowels.

-

(3)

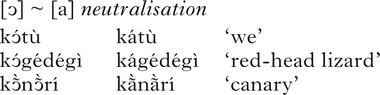

Examples of words containing each of the vowels are shown in (4). Unlike most Benue-Congo languages, Fungwa and other Kainji languages do not have ATR harmony (see Blench Reference Blench and Watters2018).

-

(4)

There are only a few words with the vowel [ɔ]. Even in those words, [ɔ] can optionally be realised as [a] in all environments, as in (5). The low frequency of words with [ɔ] plays a role in diminutive and augmentative formation, as discussed in §5.

-

(5)

All the vowels in Fungwa have nasal counterparts (6). Oral and nasal vowels have the same patterns in vowel harmony, described in more detail in §2.3. As vowel nasalisation plays no role in evaluative formation in Fungwa, the distribution of nasal vowels is not discussed in this paper.

-

(6)

In the next section, I briefly focus on the distribution of the vowels in root-controlled harmony.

2.3 Root-controlled harmony

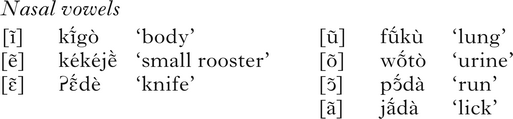

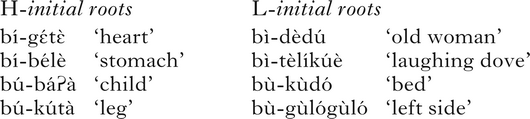

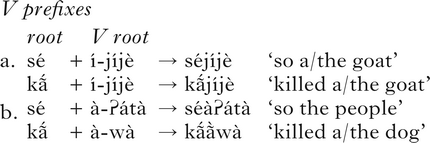

As we have seen, vowel harmony in Fungwa involves the feature [back]. The vowels of CV prefixes agree in backness with the vowel of an adjacent root syllable, as illustrated in (7).

-

(7)

The Class 9 prefix is [bi-] when the vowel of the following root syllable is front, but [bu-] when the vowel of the following root syllable is back. However, the root-internal vowels can be disharmonic, as in (7c). In such cases, the prefix vowel agrees in backness with the first vowel of the root. Agreement in backness between the prefix vowel and the vowel of the following root syllable is a form of root-controlled harmony (Clements Reference Clements1981, Reference Clements1985).

While vowels in CV prefixes undergo backness harmony, vowels in V prefixes do not, as in the two cases in (8).

-

(8)

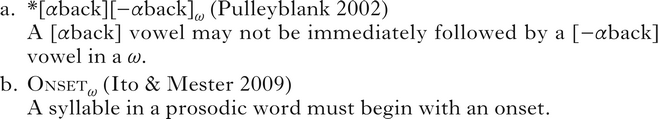

As argued in Akinbo (Reference Akinbo2019, Reference Akinbo2021), the domain of harmony, minimality and an onset condition in Fungwa is the prosodic word (ω). Following Pulleyblank (Reference Pulleyblank2002), the condition on vowel harmony can be formalised as the no-disagreement constraint *[αback][―αback]ω in (9a), which requires vowels in a ω to have the same value for the feature [back]. Following Ito & Mester (Reference Ito, Mester and Parker2009), Akinbo (Reference Akinbo2021) formalises the onset condition as the constraint Onsetω, which assigns a violation to a vowel-initial syllable (9b). The minimality requirement is not crucial to the discussion here.

-

(9)

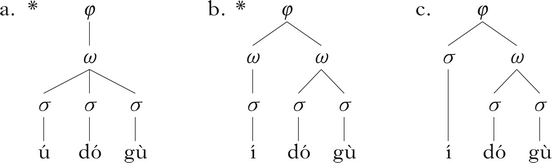

As shown in (10) for [í-dógù] ‘meat’, Onsetω prohibits the occurrence of a V prefix in ω in (10a, b), so the constraint must be satisfied by misalignment of the prefix with the ω, as in (10c). As a result of this misalignment with the harmony domain, V prefixes do not undergo vowel harmony. In other words, vowel harmony is a diagnostic for ω boundaries.

-

(10)

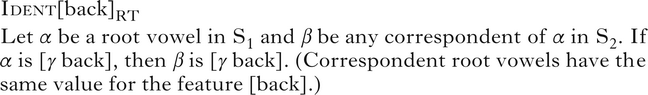

The vowels of CV prefixes obligatorily agree in backness with the root vowel, but the root vowels are invariant, even when they are disharmonic. The invariance of the root vowels is the result of the positional faithfulness constraint in (11) (Beckman Reference Beckman1998). See Akinbo (Reference Akinbo2019, Reference Akinbo2021) for a detailed account of root-controlled harmony in Fungwa.

-

(11)

As we will see in §3, root vowels violate (11) when they undergo backing and fronting in evaluative formation. These mutations can result in root-internal harmony, and determine the feature values of the targets in root-controlled harmony.

2.4 Basic tone inventory

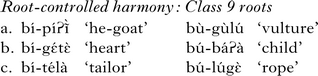

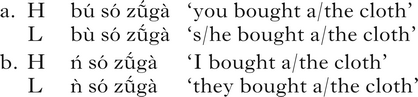

Fungwa is a tone language, like all Niger-Congo languages spoken in Nigeria, with the exception of Fulfulde (Williamson Reference Williamson1984, Elugbe & Omamor Reference Elugbe and Omamor1991). There are two tones in Fungwa, High and Low. Consider the minimal pairs in (12).

-

(12)

Fungwa has a process of tonal assimilation involving CV prefixes. As shown in (13), the prefix is [bí] or [bú] when the following TBU has an H tone but [bì] or [bù] when the following TBU has an L tone.

-

(13)

Tones are fully marked in all Fungwa examples below. They do not interact in the root-vowel mutation, so they are not discussed further here.

3 Evaluative formation in Fungwa

3.1 Evaluative formation: ‘small’-ness and ‘big’-ness

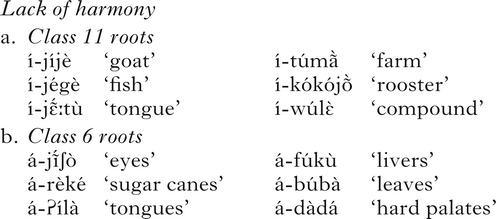

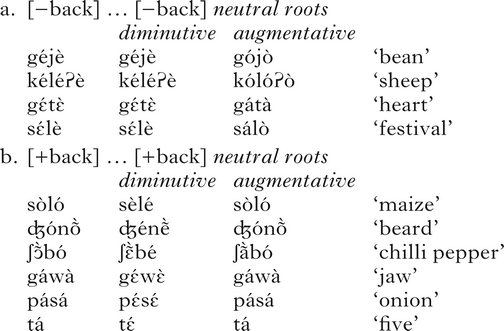

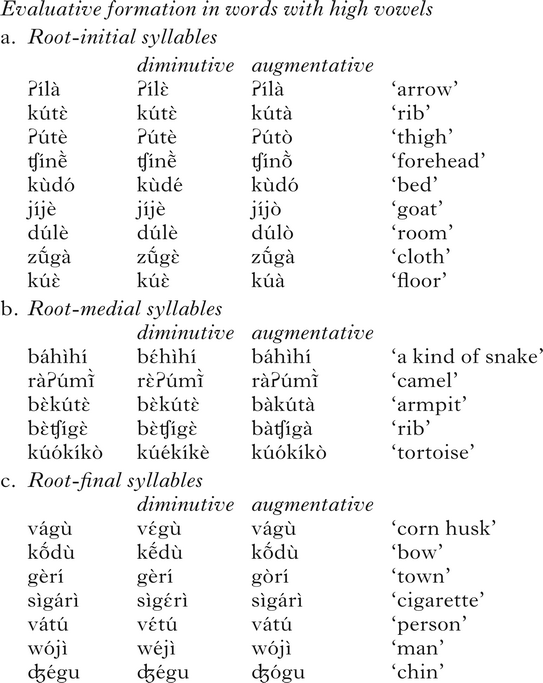

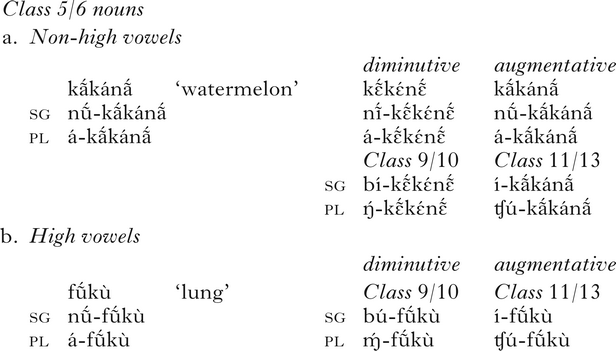

As noted in §1, Fungwa marks the notion of smallness or insignificance by fronting non-high vowels in nominal roots (diminutive formation). On the other hand, the notion of bigness or significance is marked by backing non-high vowels in nominal roots (augmentative formation). Root-vowel mutation is illustrated in (14) with neutral nominals (i.e. roots or words without diminutive and augmentative formation) involving sequences of uniformly front or back vowels.

-

(14)

In diminutive formation in (14b), the root vowel [o] is realised as [e], and vice versa in augmentative formation in (a). The mutation of the vowels [ɔ a] overlaps in diminutive formation – they are both realised as [ɛ]. In augmentative formation, [ɛ] is realised as [a]. Surface ambiguity is created by the fact that a front vowel sequence can occur both in neutral and in diminutive forms (14a), while a back vowel sequence can occur both in neutral and in augmentative forms (14b).

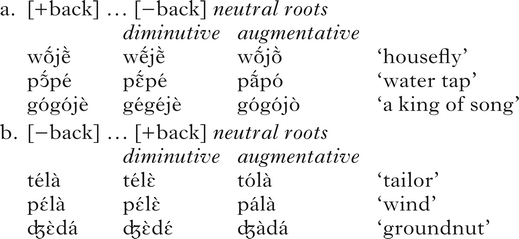

The mutations produce a sequence that is uniformly front or uniformly back even if the neutral nominal root is disharmonic. Consider the examples in (15).

-

(15)

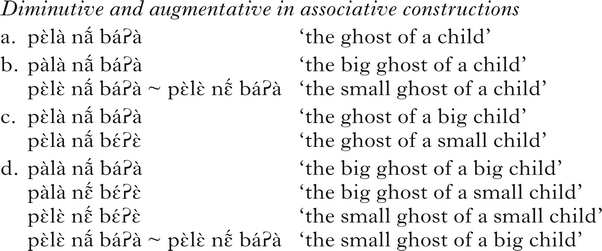

Diminutive and augmentative formations also apply to the possessum (N1) (16b), the possessor (N2) (16c) or both (16d) in an associative construction. The linker between the possessum and the possessor undergoes root-controlled vowel harmony. In this case, the linker can agree in backness with either the preceding or the following root vowel.

-

(16)

We saw in §2 that nouns can optionally bear prefixes to mark number contrast, as in (17). When a noun bears a CV prefix, the vowel of the prefix agrees with the [back] feature value of the nominal root, even when the feature value of the root vowel is from diminutive or augmentative formation. However, V prefixes do not agree in backness with the feature value resulting from root-vowel mutation (see §2.3).

-

(17)

As shown in (17a), the prefix is [bí] when the vowel of the neutral root is [―back], but [bú] when it is [+back]. When the root-initial vowel undergoes fronting, the prefix is [bí], but [bú] when the vowel undergoes backing. However, V prefixes are invariant in this same context (17b).

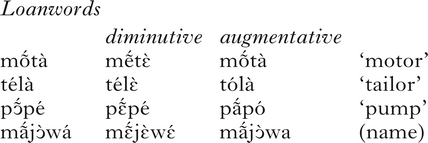

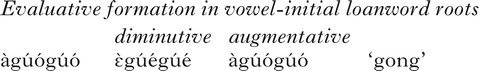

Diminutive and augmentation formation also applies in loanwords. Consider the examples in (18).

-

(18)

Diminutive and augmentative formation is not limited to nouns, but can affect other nominals, as shown in (19). The pattern of root-vowel mutations in these cases are the same as in nouns.

-

(19)

All the forms which undergo evaluative formation in Fungwa are nominals. It should be noted that the distal demonstrative [lé] in (19) does not undergo root-vowel backing. My consultants suggest that backing the distal demonstrative might ‘sound like child language’. The meaning of diminutive and augmentative formation in all these domains offers valuable insight into the semantics of evaluative morphology in Fungwa. Although the prototypical meanings of the augmentative and diminutive are big and small respectively, they also mark the distinction between significance and insignificance, good and bad, masculine and feminine, and old and young. For instance, my main consultant referred to the bandits who raided his village using the diminutive form of a pronoun because they were ‘bad’. A diminutive pronoun is also used when referring to a female. To use the diminutive instead of the augmentative form for a dignitary would be ‘disrespectful’, or suggest that the individual had an insignificant or bad status.

Except for the possessive pronouns in (19), all examples of root-vowel mutation in this section involve non-high vowels. As we will see in the next section, the possessive pronouns are some of the few cases with the mutation of consonants and high vowels.

3.2 High vowels in evaluative formation

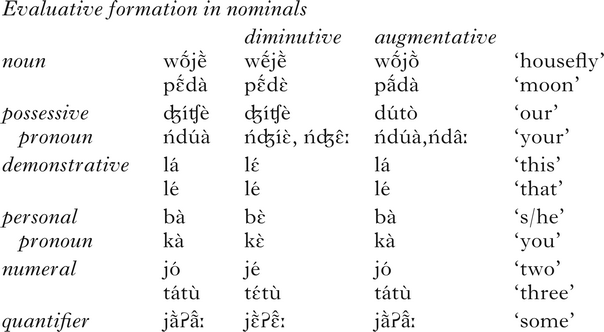

The discussion in §3.1 showed that non-high vowels undergo root-vowel mutations in diminutive and augmentative formation. In most words, the high vowels [i u] are neither backed nor fronted, even if a non-high vowel in the nominal root does show fronting or backing. Consider the example sets with [i] and [u] in (20).

-

(20)

As shown in (20a), the non-high back vowel [o] in [kùdó] is fronted to [e] in the diminutive form [kùdé], but the high vowel [u] is not fronted. Similarly, the front vowel [ẽ] in [ʧínẽ̀] is backed to [õ] in the augmentative form [ʧínṑ], but the high vowel [i] is not backed. The same holds for high vowels in root-medial and root-final environments in (20b, c).

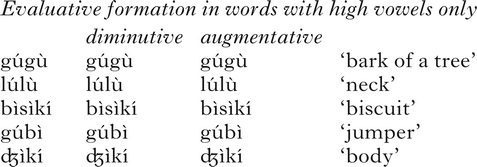

Similarly, in words with only high vowels, none of the vowels undergo root-vowel fronting or backing (21).

-

(21)

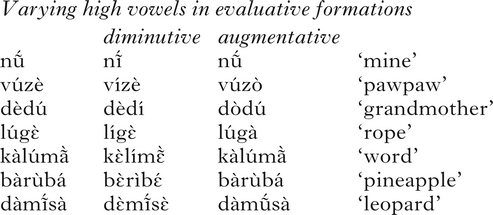

The examples in (20) and (21) show that the high vowels [i u] do not undergo root-vowel mutation. However, there are a few exceptions, illustrated in (22).

-

(22)

The distribution of the invariant high vowels is similar to that of the variable ones. For example, while the word-final high back vowel in [dèdú] ‘grandmother’ undergoes fronting in the diminutive formation [dèdí], the word-final high back vowel in [kṍdù] ‘bow’ does not undergo fronting in the diminutive formation [kẽ́dù]. Similarly, the word-final high front vowel in [mã̀lèmĩ́] ‘teacher’ undergoes backing in the augmentative form [mã̀lòmṹ], but the word-final high vowel in [kέnε̃̀rí] ‘canary’ does not undergo backing in the augmentative form [kànã̀rí]. There are about 15 forms with alternating high vowels in evaluative formations, but more than 600 forms with invariant high vowels were elicited.

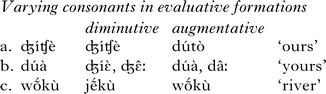

In most cases, consonants do not undergo mutation in diminutive and augmentative formation, but there are a few exceptions affecting root consonants, illustrated in (23).

-

(23)

In diminutive formation, the consonants [d] and [w] are realised as [ʤ] and [j] respectively, as in (23b, c). In augmentative formation, the consonants [ʤ] and [ʧ] are realised as [d] and [t] (23a). However, root-consonant mutation does not occur with other words with the same consonants (14)–(21). Given that the high vowel [i] does not trigger palatalisation (e.g. [í-díʃέmũ̀] ‘sneezing’ and [tìtí] ‘road’), the consonant mutation can be considered an effect of diminutive and augmentative formation, not the vowel [i]. There are only five examples with root-consonant mutation. Like forms with high vowel mutations, words with root-consonant mutations are considered exceptions.

4 Evaluative formation: analysis

We have established the following generalisations about evaluative formation in Fungwa, which prototypically expresses smallness (diminutive) and bigness (augmentative): (i) the diminutive is marked by fronting non-high vowels of nominal roots; (ii) the augmentative is marked by backing non-high vowels; (iii) high vowels are invariant in evaluative formation; (iv) consonants are invariant in evaluative formation.

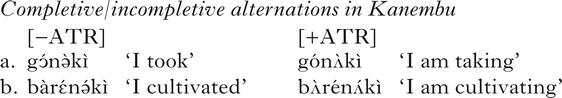

Marking diminutive or augmentative with the root-vowel mutation can be analysed as a kind of featural affixation (Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1996). To distinguish featural affixation from phonological harmony, Finley (Reference Finley2009) classifies featural affixation which result in root-internal harmony like that in Fungwa as morphemic harmony. In this section, I address each of these generalisations, and present a formal account. I take the proposal in Finley (Reference Finley2009) as a point of departure.

4.1 Featural correspondence

McCarthy & Prince (Reference McCarthy and Prince1993a, Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995) introduce Correspondence Theory within the OT framework to account for input–output faithfulness, base–reduplicant identity and other relations among phonological representations. Various constraints are proposed in the theory; the constraints that play a role here are Edge-anchoring and Contiguity. Edge-anchoring requires an element (at a particular edge) of the input to have a correspondent at a particular edge of a syntactic or a phonological domain in the output (McCarthy & Prince Reference McCarthy and Prince1993a, Reference McCarthy and Princeb, Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995), while Contiguity requires the elements in a domain to form a contiguous string (McCarthy & Prince Reference McCarthy and Prince1994, Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995).

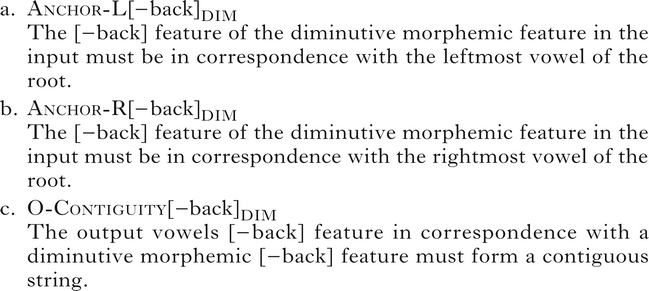

McCarthy & Prince's (Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995) definition of correspondence constraints involves segmental elements, but they note that it could be extended to elements that are bigger or smaller than a segment. To account for featural affixation, which results in root-internal harmony, Finley (Reference Finley2009) proposes morpheme-specific correspondence constraints, which are feature-based versions of the original correspondence constraints in McCarthy & Prince (Reference McCarthy and Prince1993a, Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995). Finley's constraints require correspondence between features and the edges of a relevant domain. These constraints are morpheme-specific versions of Edge-anchor and Contiguity. The diminutive morpheme formulations of the constraints are provided in (24).

-

(24)

Anchor-L[―back]DIM requires a diminutive morphemic feature to be in correspondence with the leftmost vowel of the root. Similarly, Anchor-R[―back]DIM requires a diminutive morphemic feature to be in correspondence with the rightmost vowel. If the diminutive morphemic feature is in correspondence with the rightmost and leftmost vowels of the root, no violations are assigned. To enforce the maximal extension of the diminutive morphemic feature, O-Contiguity[―back]DIM assigns a violation for each vowel that breaks the contiguous string in the realisation of the diminutive morphemic feature. The combined effect of the constraints in (24) enforces affix-triggered or morphemic harmony. Under the assumption of relativised locality (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994, Nevins Reference Nevins2010), the featural affix would to link to all root vowels.

4.2 Root-vowel mutation as featural affixation

This subsection focuses on the analysis of the root-vowel mutation, which can be accounted for with reference to the claims of autosegmental phonology (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976).

Autosegmental phonology breaks down segments into component parts or features (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976), and provides mechanics for putting these component parts together (Clements Reference Clements1985, Sagey Reference Sagey1986, McCarthy Reference McCarthy1988, Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994). Two of the claims of autosegmental phonology are that features can exist completely independently of a segment in surface or underlying representation and that there are morphemes comprised solely of a feature. Features that are completely independent of a segment in the underlying or surface representation are considered floating features. While a floating feature can be a morpheme, not all floating features are morphemic (see Leben Reference Leben1973, Reference Leben and Fromkin1978).

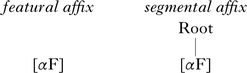

In the phonological literature, morphemic features are also referred to as featural affixes (Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1996). Like segmental affixes, featural affixes attach to edges of specific morphological domains, and are often forced away from the edges of the domain like infixes. While a segmental affix contains a bundle of phonological features with a root node, a featural affix is a feature without a root node (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976, Clements Reference Clements1985, Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994, Zoll Reference Zoll1996). Because a root node is essential to the realisation of a (floating) feature, the featural affixes are realised as part of a segment in the output. This realisation often results in a root-segment mutation. (25) shows the difference between a featural affix and a segmental affix.

-

(25)

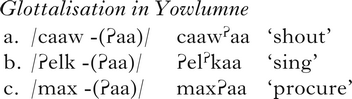

Zoll (Reference Zoll1996) makes a distinction between latent segments and dependent features. Latent segments can be realised on an epenthetic root node or as part of an existing root node, but dependent features are only realised on existing root nodes. Sonorant glottalisation, which accompanies durative formation in Yowlumne (Yokuts; U.S.A.) (26a, b), is an example of a latent segment because it can exist independently, as in (26c) (Archangeli Reference Archangeli1984, Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994, Zoll Reference Zoll1996).

-

(26)

In Kanembu (Nilotic; Nigeria and Chad), the incompletive in (27), which is marked by the tongue-root advancement of all root vowels, is an example involving dependent features (Finley Reference Finley2009).

-

(27)

Diminutive and augmentative formation in Fungwa is similar to featural affixation in Kanembu. For diminutive formation in Fungwa, I assume a [―back] diminutive morphemic feature, as in (28a). Similarly, augmentative formation involves an augmentative morpheme, which has a [+back] feature as its phonological exponent, as in (28b).

-

(28)

In the next section, I turn to a formal account of the featural affixation.

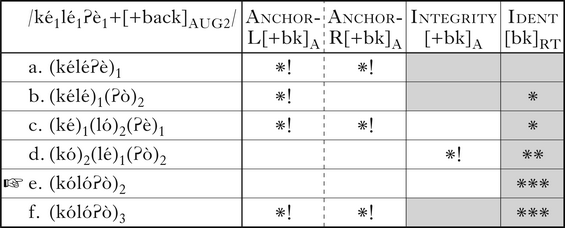

4.3 A featural correspondence account of evaluative formation

In this section I give a formal account of the realisation of the diminutive and augmentative features on all non-high vowels. The underlying assumption in this work is that the realisation of the featural affixes is relativised to root vowels, as in (29). Under this assumption, there are three possible options for the realisation of the augmentative feature (and analogously the diminutive feature): realising the augmentative morphemic feature on (i) the rightmost root vowel, (ii) the leftmost root vowel or (iii) all root vowels. The mutation of all root vowels in forms with only non-high vowels suggests that the language prefers the third option. To account for the mutation of all non-high root vowels, I use the anchoring constraints introduced in §4.1.

-

(29)

Realising the augmentative feature only on the rightmost root vowel results in a violation of Anchor-L[+back]AUG, which requires the morphemic feature to be in correspondence with the leftmost vowel of the root. If the augmentative feature is only realised on the leftmost vowel of the root, Anchor-R[+back]AUG, which requires the augmentative morphemic feature to be in correspondence with the rightmost vowel of the root, will be violated. There are three possible autosegmental representations for the realisation of the featural affix on both the leftmost and the rightmost vowels of the root morpheme: the featural affix is realised on the rightmost vowel, with a copy on the leftmost vowel (29a); it is linked to both rightmost and leftmost vowels, skipping the medial vowel (b); it is linked to all the root vowels (c).

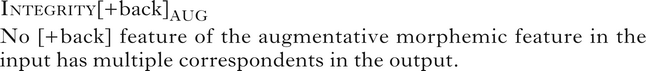

Although the option in (29a) satisfies Anchor-L[+back]AUG and Anchor-R[+back]AUG, it violates Integrity[+back]AUG in (30), which prohibits an augmentative morphemic feature from having multiple correspondents.

-

(30)

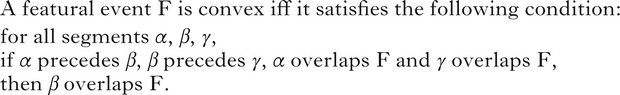

The configuration in (29b) satisfies Integrity[+back]AUG, but violates the No Crossing Condition (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976). As argued in Archangeli & Pulleyblank (Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994), the No Crossing Condition requires that all phonological relations be local, where locality is defined as respecting conditions on adjacency and precedence. Following this, Pulleyblank (Reference Pulleyblank1996) argues that representations such as (29b) have ‘contradictory precedence relations’. For example, in (29b), a direct tier-internal evaluation of precedence shows that [―back] precedes [+back]AUG, but an indirect cross-tier evaluation shows that [+back]AUG precedes [―back]. Thus (29b) is ill-formed (see Pulleyblank Reference Pulleyblank1996). Ní Chiosáin & Padgett (Reference Ní Chiosáin and Padgett1997, Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Lombardi2001) formulate adjacency and precedence as ‘convexity’, as in (31). Simply defined, convexity requires a feature F to be realised on a medial segment β if it is realised on flanking segments α and γ. According to Ní Chiosáin & Padgett (Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Lombardi2001: 127), convexity ‘holds of phonological representations without exception: in Optimality Theoretic terms, it constrains the candidate set that Gen produces’. In this case, Gen cannot produce a candidate like (29b).

-

(31)

Similarly to the statement of convexity, Pulleyblank (Reference Pulleyblank1996) argues that a representation with line-crossing, such as the form in (29b), can also be rejected on the ground that it is not phonetically viable. For instance, as the [+back] feature of the augmentative morpheme continuously spans all the root morphemes in (29b), it is not phonetically plausible for the medial vowel to be [+back] and [―back] simultaneously. Thus the gapped representation is phonetically ill-formed.

If we adopt the notion of phonological locality in Ní Chiosáin & Padgett (Reference Ní Chiosáin and Padgett1997, Reference Ní Chiosáin, Padgett and Lombardi2001), Gen cannot produce a phonetically implausible form like the line-crossing representation in (29b). Ní Chiosáin & Padgett's definition of locality can be extended to the relativised version of locality which is adopted in this work (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994, Nevins Reference Nevins2010). Under this account of locality, Anchor-L[+back]AUG and Anchor-R[+back]AUG have to be satisfied by spreading the featural affixes to all vowels, as in (29c).

In Finley (Reference Finley2009), the mutation of a medial vowel in morphemic harmony is an effect of the constraint O-Contiguity[+back]AUG, which requires the augmentative morphemic feature to form a contiguous string in the output. Under the account here, i.e. that Gen does not generate a gapped representation, a twin-peak configuration like the form in (29b) will vacuously satisfy O-Contiguity[+back]AUG (see Pulleyblank Reference Pulleyblank1996). Thus the constraint does not play a crucial role in the present account. By replacing it with Integrity[+back]AUG, we are able to rule out a twin-peak configuration for a root morpheme with only non-high vowels. Integrity[+back]AUG is ranked below the anchoring constraints in this section; this ranking is motivated in §4.4.

Given that featural affixation changes the lexical feature values of root vowels, the constraints that enforce the maximal extension of the featural affixation must be ranked above Ident[back]RT, a positional faithfulness constraint which preserves the [back] feature value of a root segment. This constraint plays a role in the account of the root-controlled harmony discussed in §2.3. In (32), I show that this set of constraints can account for featural affixation in Fungwa. Affixation is indicated by indexation, comparable to an autosegmental association line.

-

(32)

The candidate in (32a) is ruled out because the [+back]AUG morphemic feature is not realised in the output. Although the featural affix is realised on a root vowel in (b) and (c), these candidates are ruled out because the featural affix on the root vowel is not realised on the leftmost or rightmost segment of the root. Candidate (d) loses as it violates Integrity[+back]AUG. The winning candidate, (e), satisfies all the constraints except Ident[back]RT. As the source of the backing in (32f) is not the featural affix, this candidate is ruled out because the anchor constraints are able to distinguish a phonological [back] feature from a morphemic [back] feature (see Trommer Reference Trommer2015 for a similar discussion). With the augmentative-specific instantiation of the anchor constraint in (32), the ranking can also predict the correct output. As shown in §3.1 and illustrated in (33), featural affixation interacts with root-controlled harmony.

-

(33)

The candidate in (33a) satisfies the constraint on root-controlled harmony, but is ruled out because it violates the featural correspondence constraints. The candidate in (b) satisfies the featural correspondence constraints, at the cost of violating the positional faithfulness constraint, but violates the harmony constraint. The winner, (c), satisfies the featural correspondence constraints and the constraint on root-controlled harmony.

Following the account in Akinbo (Reference Akinbo2019), the domain of root-controlled harmony is a ω which is subject to an onset requirement. In this case, the vowel of the CV prefixes agreeing in backness with the feature value of the root-vowel mutation is determined by root-controlled harmony, not by evaluative formation (33a). The invariance of the V prefixes, despite the nominal root undergoing the root-vowel mutation, is consistent with this account (see §2.3).

As a root morpheme is the domain of the evaluative formation, root-vowel mutation should not to be subject to the onset condition. Thus, in a situation whereby a root morpheme is vowel-initial, our account predicts that the root-initial non-high vowel will also undergo root-vowel mutation. Although all native Fungwa roots are consonant-initial, loanwords can be vowel-initial, as in the example in (34).

-

(34)

The root-initial non-high vowels, just like other non-high vowels of the nominal roots, undergo root-vowel fronting and backing. Based on (34), the prediction that the root morpheme is the domain of evaluative formation holds true.

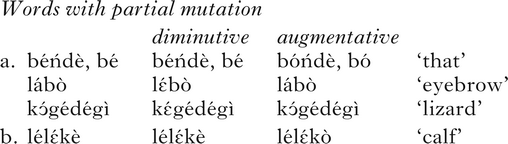

As shown in §3.1, the root vowels of a modified noun or the nominal modifier can independently undergo evaluative formation. In some cases, like mutation in complex nominal structures, not all the non-high vowels undergo root-vowel backing or fronting, as shown in (35). If we take into account that the domain of evaluative formation is a root morpheme, these examples might contain two root morphemes. An argument for this is that the form [béńdè] ‘that’ has a reduced variant [bé], as shown in (35).

-

(35)

In sum, correspondence constraints force maximal extension of the featural affixes to all root vowels, at the expense of faithfulness to the feature values of root vowels. The constraints are also able to distinguish phonologically induced backness from morphologically induced backness.

4.4 The invariance of high vowels and prominence-based licensing

We have seen that, although high vowels do not undergo diminutive or augmentative formation in most cases, there are some which do. I assume that the small number which undergo the mutations are exceptions. The invariance of most high vowels can be accounted for with reference to sonority, i.e. the relative prominence of different sounds (Clements Reference Clements, Kingston and Beckman1990, Parker Reference Parker2002, Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004). It has been established that high vowels have low sonority relative to non-high vowels, as in (36) (Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004: 4). Phonetic studies on different languages show that this height-based sonority scale is phonetically grounded (e.g. Parker Reference Parker2002). The results of these phonetic studies suggest that height-based sonority directly corresponds to the duration, oral pressure and F1 of high and non-high vowels.

-

(36)

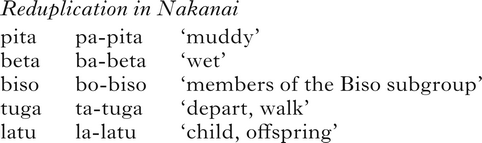

The sonority ranking of high and non-high vowels is evident in various phonological patterns in natural languages (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz1997, Spaelti Reference Spaelti1997, de Lacy Reference de Lacy2004, Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004). In certain languages, there is also an asymmetry between high and non-high vowels in stress assignment. For example, in languages such as Kobon (Madang; Papua New Guinea) (Davies Reference Davies1981, Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz1997) and Mongolian (Mongolic) (Walker Reference Walker2000), stress falls on any available non-high vowel in the domain of stress assignment. That said, there is evidence to suggest that stress may not be driven by sonority (see Shih Reference Shih2018, Shih & de Lacy Reference Shih and de Lacy2019). While sonority-driven stress might be debatable, there are uncontroversial arguments for sonority from reduplication and vowel deletion. In Nakanai (Oceanic; Austronesia) in (37), the CV-shaped reduplicant copies the most sonorous vowel of the base (Johnston Reference Johnston1980, Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004).

-

(37)

A language-internal argument for the low prominence of high vowels in Fungwa comes from the V prefixes in vowel hiatus contexts (38). Recall in this regard that only vowels [i a] occur as vowel-initial prefixes. A V prefix with [i] in a vowel hiatus context is elided, but a V prefix with [a] is not. Similar patterns of hiatus resolution are found in Yorùbá (Orie & Pulleyblank Reference Orie and Pulleyblank2002) and other languages (see Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004).

-

(38)

In the literature (e.g. Itô Reference Itô1986, Zoll Reference Zoll1996, Walker Reference Walker2005, Reference Walker2011), the association of a phonological element (e.g. stress, place features and tone) with the most prominent position has been argued to be the effect of a prominence-based licensing condition, which requires a phonological element P to occur in a prominent position. Just as vowels that are prominent (in quality or quantity) are better heads in (37), prominent segments (i.e. non-high vowels) are better licensors for featural affixes in Fungwa. Given the preference for the most sonorous vowels, I propose that featural affixation in Fungwa involves prominence-based licensing conditions which prohibit the realisation of the diminutive and the augmentative morphemic features on a prosodically weak segment. Consequently, the featural affixes are not realised on high vowels, due to their low prominence.

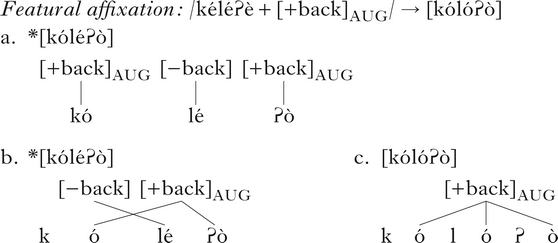

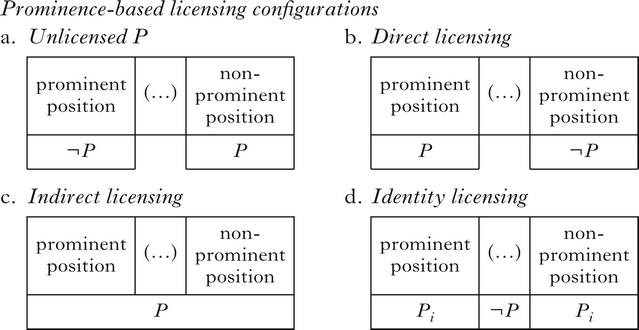

In her work on vowel patterns in various languages, Walker (Reference Walker2011) proposes three configurations for the representation of a vocalic property P in a prominent position. These configurations are direct licensing, indirect licensing and identity licensing, and are presented schematically in (39b–d).

-

(39)

The top row in each case contains cells with prominent and non-prominent positions, while the bottom row contains cells that represent the presence or absence of a vocalic property P. If P appears immediately below the cell of a position, this signifies that the vocalic property P occurs in that position. The appearance of ¬P immediately below the cell of a position signifies that the vocalic property P does not occur in that position. For instance, prominence-based licensing disfavours the configuration in (39a), because P is not expressed in the prominent position. However, licensing favours the expression of P in the other configurations (39b–d). In direct licensing, (39b), P is only expressed in a prominent position, and is prevented from appearing elsewhere. In the case of indirect licensing, (39c), P spans both prominent and non-prominent positions, without interruption. In identity licensing, (39d), coindexed instances of P are present in prominent and non-prominent positions, and may be separated by an intervening element. Walker (Reference Walker2011) proposes licensing for vocalic properties, but this can be extended to morphemic features.

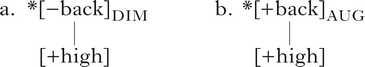

The fact that evaluative morphemic features are only realised on non-high vowels suggests prominence-based direct licensing. We can achieve direct licensing with a markedness constraint, such as the diminutive-specific constraint in (40a). The augmentative-specific instance of the constraint (40b) also prohibits the realisation of the augmentative feature on a high vowel.

-

(40)

As the formulation of the constraints does not stipulate how prevention of unlicensed constituents is accomplished, the schema is neutral as to whether the constraint is satisfied by not parsing the morphemic feature, by deleting the morphemic feature or by lowering of the high root vowels. In the latter case, it is possible to imagine a situation whereby a high vowel is lowered to a mid vowel in order to satisfy the licensing constraint. Potentially, this lowering results in the violation of a faithfulness constraint, such as Ident[high], which requires the [high] feature value of an input vowel to be identical to that of its output correspondent. Since such lowering does not occur in Fungwa, in order to satisfy the licensing constraint, the faithfulness constraint, in this case Ident[high], needs to be ranked above the anchoring constraints.

To satisfy the licensing condition, we are now left with the options of deleting or floating the phonetic exponents of the evaluative morphemes. Similar to morphemes without zero phonetic exponents across languages (Aone & Wittenburg Reference Aone and Wittenburg1990, Bauer & Valera Reference Bauer, Valera, Bauer and Valera2005), neither deletion nor floating of the phonetic exponents should affect the interpretation of the evaluative morphemes. For analytical purposes, the assumption here is that the phonetic exponents of the evaluative morphemes float when there is no legitimate licensor. In this case, the evaluative morphemes are comparable to floating tones (Hyman Reference Hyman1979, Pulleyblank Reference Pulleyblank1986), except that they have no audible effects. Given that the phonetic exponents have no audible effect in this instance, how can a listener interpret the evaluative morphemes? Plausible cues for the interpretation of the evaluative morphemes are their interaction with noun-class prefixes, shown in (41).

-

(41)

For example, when a noun undergoes diminutive formation and is morphologically marked for number, the nominal stem may either take its intrinsic class prefix or the prefix of Classes 9 and 10. When it undergoes augmentative formation and is morphological marked for number, the stem may either take its intrinsic class prefix or the prefix of Classes 11 and 13. This interaction between the evaluative morphemes and the noun-class prefixes occurs in all nominals, regardless of their vowels. Notably, this is the only phonetic cue for evaluative formation when a noun has only high vowels. According to Akinbo (Reference Akinbo2021: 194), this is ‘a result of the overlap between the semantics of evaluative morphemes and the characteristic features of nouns which belong to’ Classes 9/10 and 11/13 (see Akinbo Reference Akinbo2021: ch. 6 for further discussion). The interaction between noun-class prefixes and evaluative formation is not peculiar to Fungwa; it is also found in Bantu languages such as Swahili (Carstens Reference Carstens1991), Nata (Gambarage Reference Gambarage2019), Shona (Déchaine et al. Reference Déchaine, Girard, Mudzingwa and Wiltschko2014), Bemba and other languages (see Maho Reference Maho1999).

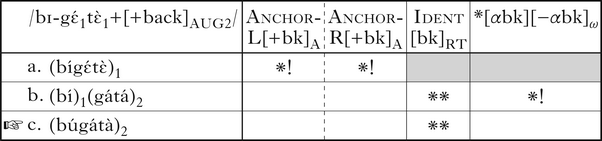

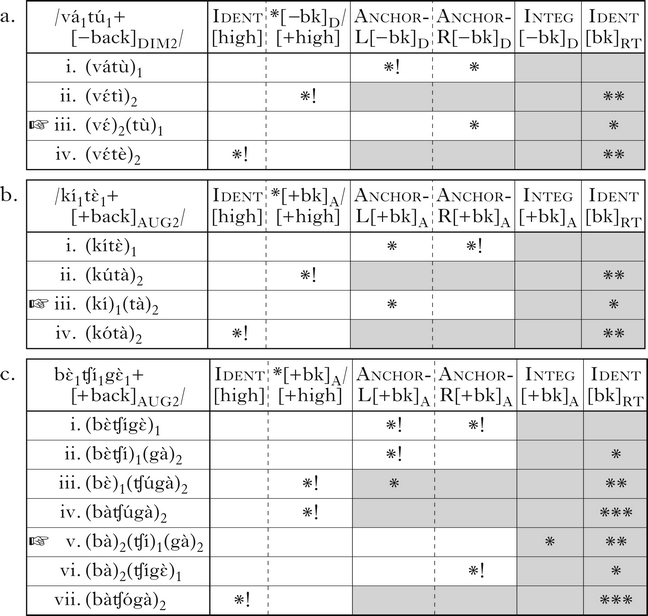

To formally account for the invariance of high vowels, the constraint which drives the licensing condition is ranked above the constraints on the realisation and the maximal extension of the featural affixes. This account is illustrated in the tableaux in (42), for (a) [vέtù] ‘person (dim)’, (b) [kítà] ‘cockroach (aug)’ and (c) [bàʧígà] ‘rib (aug)’.

-

(42)

The winning candidates in (42a) and (b) satisfy the licensing condition, at the cost of violating one of the constraints on left and right anchoring. This account suggests that the licensing conditions are ranked above the constraints on left and right anchoring.Footnote 2 Candidates (42c.ii) and (42c.vi) satisfy the licensing constraint by realising the featural affix on the rightmost or leftmost vowel of the root, but are ruled out for violating either Anchor-L[+back]AUG or Anchor-R[+back]AUG. That candidate (42c.v) wins despite violating Integrity[+back]AUG suggests that this constraint is ranked below Anchor-L[+back]AUG and Anchor-R[+back]AUG. In sum, the licensing condition prohibits the realisation of the featural affixes on high vowels.

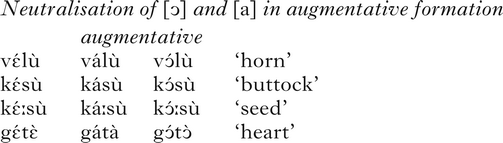

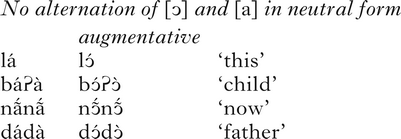

5 The vowels [ɔ] and [a] in augmentative backing

I have argued that the augmentative feature has a [+back] feature as its phonetic exponent. Under this account, we would expect the vowel [ɛ] to be realised as [ɔ] in augmentative formation, given that mutation of [ɛ] to [a] involves both backing and lowering. Interestingly, it is also possible for [ɛ] to alternate between [a] and [ɔ] in augmentative formation, as in (43).

-

(43)

This section focuses on the optional alternation by considering the status of [ɔ] in the language.

As mentioned in §2.2, [ɔ] occurs in only a few words. Even in those words, the vowel can optionally be produced as the vowel [a] in a neutral form, as in (5) above. The only exception in my data is the word [nɔ~́ʃì] ‘four’, which does not involve the optional realisation of the vowel [ɔ] as [a].

[ɔ] in neutral forms can optionally be realised as [a], but the opposite is not true. For example, a root morpheme with only back vowels may be interpreted as an augmentative form. However, when [a] in a nominal root with only back vowels is realised as [ɔ], the noun is always interpreted as an augmentative form, as in (44).

-

(44)

Among all the vowels of Fungwa, only [a] and [ɔ] are involved in optional variation. It bears mentioning that older speakers optionally produce [ɔ] as [a] in neutral forms in a natural speech situation, but younger speakers invariably produce the vowel [ɔ] as [a] in the same situation.

The fact that the vowel [ɔ] can optionally neutralise with [a] in a neutral form and vice versa in augmentative formation suggests that the vowel [ɔ] is undergoing a merger with [a]. A very low type/token frequency of the vowel [ɔ] also points to a merger in progress.

6 Evaluative formation and sound symbolism

In this section, I compare the form and meaning of the root-vowel mutation in Fungwa with the properties of diminutive and augmentative morphemes across languages.

Diminutive and augmentative are categories of evaluative morphology (Scalise Reference Scalise1984, Stump Reference Stump1993, Bauer Reference Bauer1997). In natural languages, evaluative morphology is intertwined with phonetic iconicity or sound symbolism (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1922, Gregová et al. Reference Gregová, Körtvélyessy and Zimmermann2010). According to Plank & Filimonova's (Reference Plank and Filimonova1996–2001, Reference Plank and Filimonova2000) universals 1926 and 1001, diminutives tend to contain high front vowels, whereas augmentatives tend to contain back vowels. For example, in Siwu (Volta Region, Ghana), the words that refer to smallness and bigness tend to contain front vowels (e.g. [pimbilii] ‘small belly’) and back vowels (e.g. [pumbuluu] ‘enormous round belly’) respectively (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Blasi, Lupyan, Christiansen and Monaghan2015). While sound symbolism in evaluative morphology is mostly found in vowels (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1922, Reference Jespersen and Jespersen1933, Sapir Reference Sapir1929, Bentley & Varon Reference Bentley and Varon1933, Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Blasi, Lupyan, Christiansen and Monaghan2015, Kawahara et al. Reference Kawahara, Noto and Kumagai2018), consonants have also been connected to phonetic iconicity. Palatal consonants tend to be associated with the notion of smallness (Ultan Reference Ultan, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978, Bauer Reference Bauer1996, Alderete & Kochetov Reference Alderete and Kochetov2017). If we take into account that palatalisation also involve the feature value [―back], we see a parallel between the symbolic association of palatal and [―back] vowels with the notion of smallness (i.e. diminutive) (see Alderete & Kochetov Reference Alderete and Kochetov2017).

Sound symbolism also exists in the domain of naming. In Japanese, for instance, initial high vowels are symbolically associated with the names of smaller and lighter characters in the Pokémon series of Japanese video games (Kawahara et al. Reference Kawahara, Noto and Kumagai2018). An experimental study also showed that English-speaking participants associated front vowels with positive brand names, whereas back vowels were associated with negative image branding (Lowrey & Shrum Reference Lowrey and Shrum2007). Other studies, based on more than twenty language samples, suggest that the link between evaluative morphology and sound symbolism is not universal, but language- or area-specific (Ultan Reference Ultan, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978, Bauer Reference Bauer1996, Gregová et al. Reference Gregová, Körtvélyessy and Zimmermann2010, Körtvélyessy & Stekauer Reference Körtvélyessy and Stekauer2011).

The involvement of root-vowel fronting and backing in diminutive and augmentative formations in Fungwa is consistent with the connection between evaluative morphology and sound symbolism.

Like diminutive and augmentative formation in Fungwa, there is evidence to suggest that many phonological patterns with sound symbolism involve featural affixation. For example, Alderete & Kochetov (Reference Alderete and Kochetov2009) analyse fifty cases of expressive palatalisation with sound symbolism as involving the feature [―back]. Similarly, vowel mutation in Korean ideophones has also been considered to be the effect of a featural affix with multiple features (Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1996, Finley Reference Finley2009).

In the next section, I present the theoretical implications and the basis of the sound-size symbolism in Fungwa.

7 Theoretical implications of the diminutive and augmentative

The discussion in §6 suggests that the expression of the diminutive and augmentative with root-vowel fronting and backing respectively is a kind of sound-size symbolism. Sound symbolism is often excluded from the discussion of core linguistic theory. Kawahara (Reference Kawahara2020: 1) notes that the exclusion of sound symbolism from phonological theories is due to the persistent view that ‘the relationship between sounds and meaning is arbitrary’. Observing the parallels between sound symbolism and ‘core’ phonological patterns, Kawahara (Reference Kawahara2020) argues for the inclusion of sound symbolism in phonological theories. Alderete & Kochetov (Reference Alderete and Kochetov2017) put forward a similar argument in their formal account of expressive palatalisation across languages. In line with these arguments, this section focuses on the significance of evaluative formation in Fungwa for phonological theories.

As noted in Kawahara (Reference Kawahara2020), another motivation for excluding sound-size symbolism from phonological theory is that the evidence for it mostly comes from ideophones (e.g. Awoyale Reference Awoyale1981, Mphande Reference Mphande1992, Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2011, Reference Dingemanse2012, Ibarretxe-Antuñano Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano2017), probabilistic tendencies in lexicon (e.g. Ultan Reference Ultan, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978, Bauer Reference Bauer1996, Gregová et al. Reference Gregová, Körtvélyessy and Zimmermann2010, Körtvélyessy & Stekauer Reference Körtvélyessy and Stekauer2011), psycholinguistic experiments (e.g. Sapir Reference Sapir1929, Ramachandran & Hubbard Reference Ramachandran and Hubbard2001, Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Schuerman, Reinisch, Tufvesson and Mitterer2016) and infant-directed speech (e.g. Laing et al. Reference Laing, Vihman and Keren-Portnoy2017, Perry et al. Reference Perry, Perlman, Winter, Massaro and Lupyan2018). As the evidence is stochastic and not part of the core morphophonology, sound symbolism is excluded from the models of generative theories which hold that phonological knowledge should be categorical rather than stochastic (Kawahara Reference Kawahara2020). The nature of the phonetic exponents of the diminutive and augmentative morphemes in Fungwa provides a strong argument for the existence of sound symbolism in core morphophonological grammar. The sound-size symbolism in the diminutive and augmentative morphemes of Fungwa is categorical, and applies both to native words and to loanwords. The root-vowel mutation that results from the realisation of the featural affixes interacts with another phonological alternation, root-controlled vowel harmony. Most importantly, the constraints for arbitrary featural affixes (i.e. featural correspondence; Finley Reference Finley2009) are also able to account for the realisation of the non-arbitrary featural affixes.

A recurrent question in the study of sound-size symbolism concerns its phonetic basis. In an attempt to account for the acoustic cues that underline sound-size symbolism, Knoeferle et al. (Reference Knoeferle, Li, Maggioni and Spence2017) conducted two experiments on sound-size judgement. The results of the study suggest that the size of an object correlates positively with the values of intensity and first formant (F1), but negatively with fundamental frequency (F0) and second formant (F2) values: (i) the lower the values of intensity and F1, the lesser the size of the object, and vice versa; (ii) the higher the values of F0 and F2, the lesser the size of the object, with the opposite being the case for lower values of F0 and F2. That said, Knoeferle et al. (Reference Knoeferle, Li, Maggioni and Spence2017: 4) find no ‘significant main effects of f0 and intensity on size judgments’ in their experiments. The sound-size symbolism in Fungwa is in line with Knoeferle et al.'s findings. In this case, front vowels are associated with smallness and back vowels with bigness (i) because the values of intensity and F1 are lower in front vowels than in back vowels, and (ii) because the values of F2 and F0 are higher in front vowels than in back vowels. This suggests that, just like core phonological patterns, sound-size symbolism is phonetically grounded.

One methodological challenge with sound-symbolism experiments such as those of Knoeferle et al. (Reference Knoeferle, Li, Maggioni and Spence2017) is that they mostly involve pairing of acoustic signals with objects. As noted in Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Perlman and Perniss2020: 4), when form and meaning are presented separately, it is hard to guess their meaning, ‘but given both form and meaning, we can see iconic relations between the two’. This suggests that iconic relations between form and meaning have a third element that mediates the symbolic association. To account for the mediating factor in sound-size symbolism, Ohala (Reference Ohala1984, Reference Ohala, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994) proposes the ‘frequency code’ hypothesis, according to which the association of diminution with a high-pitched vowel and augmentation with a low-pitched vowel evokes biological or physiological traits of the acoustic sources. One of the arguments for the frequency code hypothesis is that the human voice can convey information such as sex and age. For example, females typically have higher F0 and lower voice intensity than males (Simpson Reference Simpson2009), as do children when compared to adults (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999, Traunmüller & Eriksson Reference Traunmüller and Eriksson2000). The acoustic differences stem from the natural principle that longer vibrating bodies (e.g. male vocal cords) have lower frequencies when compared to shorter ones (e.g. female vocal cords) (Titze Reference Titze1989, Lee et al. Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999). There is evidence to suggest that humans utilise this knowledge of bioacoustics to their own advantage. For example, studies have shown that men lower their voice frequencies in order to appear bigger or more attractive (Fraccaro et al. Reference Fraccaro, O'Connor, Re, Jones, DeBruine and Feinberg2013, Babel et al. Reference Babel, McGuire and King2014, Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Compton, Heyman and Jiang2020). Similar behaviour is found in animals (Ohala Reference Ohala, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994). That the effects of age and sex on voice facilitate sound-size symbolism is further established if we consider that the possible meanings of the diminutive and augmentative morphemes in Fungwa include ‘feminine’ vs. ‘masculine’ and ‘young’ vs. ‘old’.

We now return to the issue of phonetic grounding in sound symbolism by focusing on the fact that non-high vowels are the preferred segments for the realisation of the featural affixes. As proposed in this paper, the preference for non-high vowels over other segments in the realisation of featural affixes is the result of a prominent-based licensing condition which requires evaluative morphemes to be realised on phonetically prominent segments. The licensing of featural affixes on non-high vowels is a kind of positional asymmetry, which involves assigning privilege to a linguistic element for psycholinguistic or phonetic prominence. Many cases of positional asymmetry have been reported in arbitrary phonological patterns (Beckman Reference Beckman1998, Howe & Pulleyblank Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2004), but relatively few cases have been reported for phonological patterns with sound symbolism. Even the few cases of positional asymmetry in sound symbolism are from probabilistic tendencies (Haynie et al. Reference Haynie, Bowern and LaPalombara2014) and psycholinguistic experiments (Kawahara et al. Reference Kawahara, Shinohara and Uchimoto2008). The licensing of featural affixes on non-high vowels in Fungwa presents categorical and natural language evidence for phonological asymmetry in sound symbolism.

Evaluative formation in Fungwa challenges the notion that the relation between sound and meaning is completely arbitrary. I have shown not only that the association between sound and meaning in evaluative formation is symbolic, but also that it shares some features with arbitrary phonological patterns cross-linguistically.

8 Summary and conclusion

This paper has presented a description and analysis of the root-vowel mutations of nominals in Fungwa. In the root-vowel mutations, the diminutive is marked by fronting non-high vowels of nominal roots, whereas the augmentative is marked by backing non-high vowels. Although the non-high vowels of nominal roots undergo fronting or backing, the high vowels in nominal roots are neither front nor back.

The root-vowel mutations in diminutive and augmentative formation are caused by morphemic features, also known as featural affixes. The morphemic features are evaluative morphemes, because they have the prototypical meanings of evaluative morphology. The fronting and backing in the realisation of the morphemic features is consistent with phonetic iconicity in evaluative morphology across languages.

Formally, the realisation and the maximal extension of the morphemic features are the effect of featural correspondence constraints. These constraints are able to distinguish phonological features from the morphemic ones. Considering that non-high vowels are more sonorous in natural languages than high vowels, the realisation of the morphemic features on non-high vowels is the effect of a prominence-based licensing condition, which requires the morphemic features to coincide with a prominent segment. The prominence-based licensing condition assigns a violation mark to a morphemic feature that coincides with a non-prominent segment.

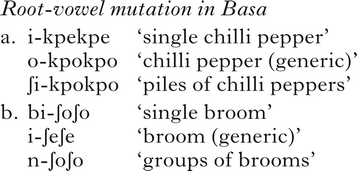

Diminutive and augmentative formation, as reported here, has not been reported in other Kainji languages. However, the root-vowel mutations of the diminutive and the augmentative formation in Fungwa are similar to the root-vowel mutation reported in Basa, an East-Kainji language (Blench Reference Blench and Watters2018). Consider the examples in (45).

-

(45)

According to Blench (Reference Blench and Watters2018: 98), the motivation for the root-vowel mutation is ‘more difficult to explain’. It would be interesting to explore whether the root-vowel mutation in Basa is the result of a morphological process such as evaluative formation in Fungwa. To determine whether evaluative formation is a family-wide phenomenon, future research on these languages should document evaluative formation.

In sum, the evaluative morphemes in Fungwa are iconic featural affixes. Considering that the featural affixes are only realised on non-high root vowels, the realisation of the featural affixes is prominence-based. Featural affixation in Fungwa also suggests that the phonological knowledge of sound-size symbolism is phonetically and biologically grounded, and may be categorical.