Introduction

Although significant progress has been made in the conservation of African wildlife, much remains to be done to ensure the long-term viability of small populations of many species. Successful conservation strategies depend on availability of human capacity across a range of disciplines, from the natural and social sciences to law enforcement and business administration (Black et al., Reference Black, Groombridge and Jones2011). Many academic and technical programmes are providing training for conservation professionals. Regional wildlife colleges in Cameroon and Rwanda (serving West and Central Africa), Tanzania (serving Eastern Africa) and South Africa (serving Southern Africa) are playing significant roles in addressing specific needs of the wildlife management profession in their respective regions (Scholte, Reference Scholte2003).

Since the 1960s, when many African countries gained independence, the science and practice of wildlife conservation has evolved from a colonial emphasis on protected areas and trophy hunting to community-based approaches for wildlife management (Jones, Reference Jones2006; Garland, Reference Garland2008; Child & Barnes, Reference Child and Barnes2010; ’t Sas-Rolfes, Reference ’t Sas-Rolfes2017). Protected areas have continued to gain prominence as effective tools for safeguarding wildlife and generating revenue through ecotourism. At the same time, the importance of engaging local communities and private landowners in wildlife management and conservation has also emerged as a major innovation in parts of the continent, especially eastern and southern regions (Hulme & Murphree, Reference Hulme and Murphree1999; Adams & Hulme, Reference Adams and Hulme2001; Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Adams and Murombedzi2005). This evolution has also influenced the nature of the wildlife profession in Africa, which started from an emphasis on park guards and rangers for management of protected areas to social scientists and anthropologists focused on empowering local communities as custodians of wildlife (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Csányi and Field1998).

Training programmes across the continent are also evolving to meet the growing demand for expertise. Because threats to wildlife have continued to increase, the wildlife conservation profession requires new and diverse skills beyond those offered by traditional academic training (Black et al., Reference Black, Groombridge and Jones2011). Following the definition by Manolis et al. (Reference Manolis, Chan, Finkelstein, Stephens, Nelson, Grant and Dombeck2008), conservation leadership requires suitable skills to inspire and mobilize others towards achieving purposeful change. Interpersonal skills are perceived by conservation professionals as the most important competences for effective leadership (Englefield et al., Reference Englefield, Black, Copsey and Knight2019). This is crucial because wildlife conservation professionals are increasingly confronted with complex and challenging problems (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Jones, Sandbrook, Nelson, Copsey and Doak2020). Yet according to O'Connell et al. (Reference O'Connell, Nasirwa, Carter, Farmer, Appleton and Arinaitwe2017), although effective leadership is essential for conservation success, there is currently insufficient understanding of what conservation leaders are doing, and what they should be doing, to be effective.

Manolis et al. (Reference Manolis, Chan, Finkelstein, Stephens, Nelson, Grant and Dombeck2008) identified two types of conservation science leadership: shaping conservation science through path-breaking research, and advancing the integration of conservation science into policy, management and society at large; they considered the integrative type of leadership as representing the greatest opportunity for improving conservation effectiveness. Leadership and capacity development initiatives should therefore address technical competences for conservation professionals, as well as soft and people skills that will prepare them as influencers and drivers of innovation. This was the rationale behind Mentoring for ENvironmental Training in Outreach and Resource conservation (MENTOR), launched in 2007 by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) through a collaborative effort with various partners to support conservation leadership and capacity development across Africa. The MENTOR programme was founded on the conviction that a combination of training and mentorship is key to strengthening leadership capabilities and competences for conservation professionals to tackle emerging challenges facing species and ecosystems. The specific aim was to develop a cadre of African leaders who would ultimately apply their acquired knowledge and professional skills as individuals or through teamwork to influence conservation outcomes.

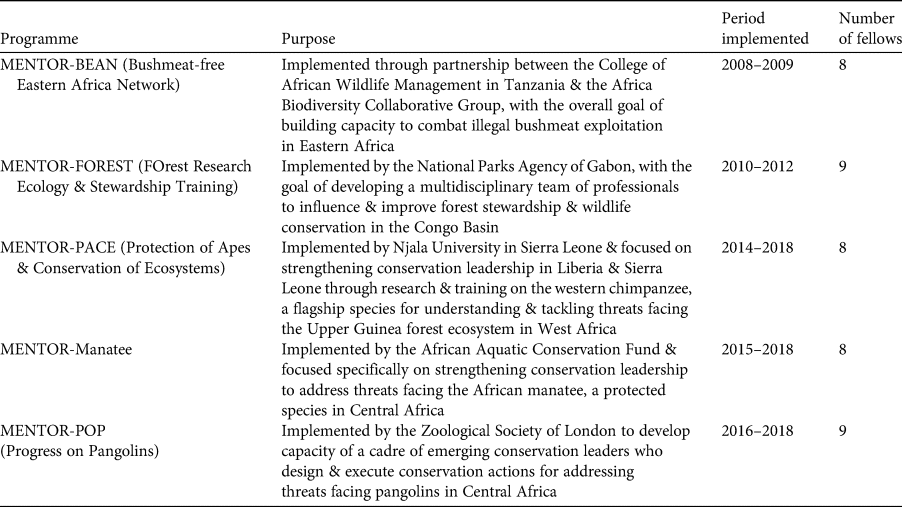

During 2007–2018, five MENTOR programmes were implemented, focusing either on conservation of a globally threatened wildlife species or tackling the threats facing wildlife (Table 1). A primary focus was on illegal exploitation of wildlife for bushmeat, and threats facing the Congo Basin forest and six globally important mammals (the western chimpanzee Pan troglodytes verus, African manatee Trichechus senegalensis, black-bellied pangolin Phataginus tetradactyla, white-bellied pangolin Phataginus tricuspis, giant pangolin Smutsia gigantea and ground pangolin Smutsia temminckii). Each 18–36 month programme was designed to combine rigorous academic and field-based training with mentoring, team building and experiential learning for 8–9 fellows. MENTOR was originally designed to be a series of programmes in different regions of Africa to develop teams to address species conservation and tackle threats. As a result of lessons learnt from having specific modules on team building, conflict management, and adaptive management for conservation planning and project implementation, these aspects were subsequently incorporated into all later programmes. The five programmes together involved 42 professionals with diverse backgrounds and expertise across 11 countries. By targeting specific wildlife species and ecosystems, participating fellows acquired knowledge and skills that enabled them to identify practical solutions and implement actions.

Table 1 Summary profile of the five Mentoring for ENvironmental Training in Outreach and Resource conservation (MENTOR) programmes initiated in 2007 by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Here we report on an ex-post assessment of the programmes and their impacts on the fellows. We focused on three aspects: (1) strategic relevance and design with respect to the conservation priorities, (2) progress, effectiveness and impact on the fellows, and (3) sustainability. We used informant interviews and online surveys for data collection and performed statistical analysis to assess how participating fellows benefited from the programmes relative to a comparative group. In February 2020, we discussed our preliminary findings during a forum organized and hosted by Njala University in Sierra Leone, which brought together many of the participating fellows and mentors from various partner institutions across Africa. We present the findings of the assessment and discuss the potential for linking training and mentorship as a strategy for developing conservation leadership.

Methods

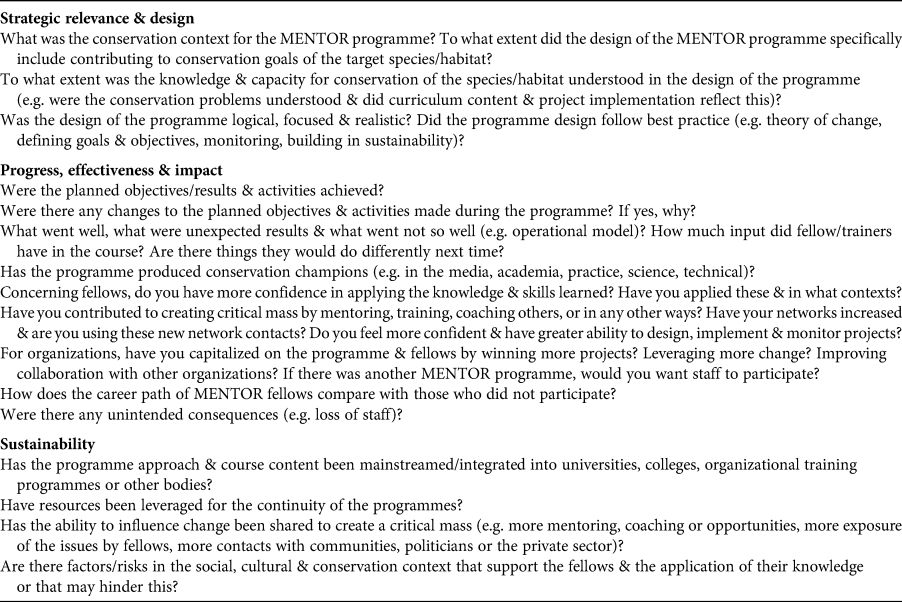

The study was conceived by IA-B, AL and MIB at Njala University, where one of the programmes was implemented, with the specific objective of assessing how the MENTOR approach affected the fellows. Overall design of the evaluation emerged from a workshop on monitoring and evaluation of training programmes organized for staff of Njala University with support from the USFWS. During the workshop, a group of the co-authors (AL, IA-B, JJ, PJK, ES-M, PFYT, RW, SO) created an initial set of questions based on standard evaluation criteria (Table 2). We then adapted these higher-level questions for the assessment following Kirkpatrick's Hierarchy, which is often used as a basis for evaluation in the training and development field (Kurt, Reference Kurt2016). The model has four levels used in the evaluation process: Level 1 looks at how valuable the training was to the individual; Level 2 explores what the participant has learned and what they can do differently as a result; Level 3 is concerned with whether the individual is applying what was learned; and Level 4 is about the outcomes of the training and whether it was worth the effort and investment (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick2006).

Table 2 Focal evaluation questions used to design key informant interviews and online surveys covering three aspects of the MENTOR programmes: (1) strategic relevance and design with respect to the conservation priorities, (2) progress, effectiveness and impact on the fellows, and (3) sustainability.

To determine the impact of the MENTOR programmes, we adopted a quasi-experimental approach. Constraints that exclude some of the more rigorous approaches include, but are not limited to: inability to locate and obtain a response from all trainees, the varying lengths of time between the training and the self-assessment, lack of any pre-training assessment (except for the choice to include the participant in the programme or not), the subjective nature of self-assessments, the small sample size, whether candidates not accepted for the programme constitute a valid control group, and the small number of potential beneficiaries. Mixed methods were employed for data collection, including an online survey, key informant interviews and a document review.

We used key informant interviews to unravel issues around the overall MENTOR programme approach, including perceptions of partnering institutions on strengths, weaknesses and prospects for scaling up the approach. All interviews with fellows and other relevant stakeholders associated with each programme were conducted by an evaluation team comprising four co-authors from Njala University (JJ, PJK, ES-M, PFYT) and two independent consultants (AN, SO). Because we did not set out to make any comparisons between the individual programmes, there was no inherent risk of introducing biases or conflicts of interest with this approach. Nevertheless, to avoid any such risk, the evaluators were independent from the MENTOR programme they evaluated. The interviews entailed visits to countries where the programmes were based and the majority of the fellows located. In some cases where face-to-face interactions were not possible, we used virtual means of connecting with individuals. We complemented the informant interviews with online surveys and review of relevant documents provided as background information on each programme, including self-assessments and progress reports.

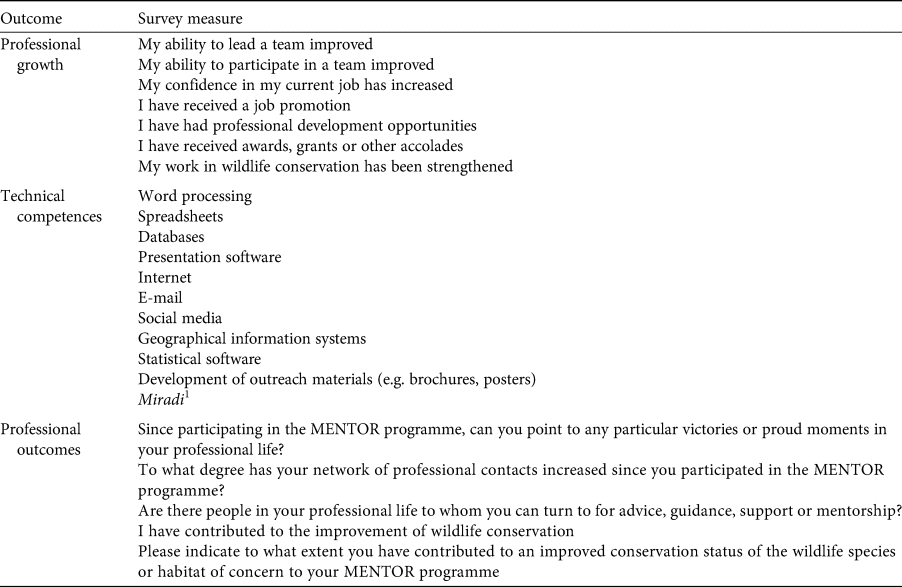

To examine the direct effects of the programmes, we compared fellows who successfully completed the programmes (the treatment group) to a quasi control group of 16 individuals who had either applied to participate in the programmes but were not selected or were currently working in the conservation sector. This control group of non-fellows was selected taking into consideration the criteria that were originally applied by the respective MENTOR programmes. We conducted the comparative analysis on specific measures in three categories: professional growth, technical competences and professional outcomes (Table 3). Participants were required to rate the measures in accordance with their personal experience. Using the online survey, we obtained data from 31 of 42 fellows (some were not contactable or had left the conservation sector) and 16 non-fellows.

Table 3 Outcome categories and survey measures for the quantitative evaluation. Participants provided ratings on three outcomes based on survey measures listed for each. Ratings of survey measures were used to compare fellows and the control group using (1) treatment effect based on standard deviations and (2) log-likelihood.

1 Allows conservation practitioners to design, manage, monitor and learn from their projects to meet their conservation goals more effectively, following a process laid out in the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation (MIRADI, 2021).

Respondents were asked to rate their skills and capability as extensive, moderate, some or none. Because of likely differences in the confidence of respondents we cannot be certain that those claiming a particular level of knowledge of a topic are of equivalent skill. To measure the effects of the programme on fellows, we employed two complementary approaches: treatment effect based on standard deviations (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) and log-likelihood (Bland & Altman, Reference Bland and Altman2000; Szumilas, Reference Szumilas2010).

For the treatment effect we recoded the responses none, some, moderate and extensive to numeric scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively, and responses of yes and no to 1 and 0, respectively. These scores were then normalized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. For each question the mean response of all respondents is therefore zero, the standard deviation is one, and each question has approximately the same range of normalized values. However, the data set is small and the raw data are both categorical and skewed. For treatment effects expressed in standard deviation units, a basic convention (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) is that an effect size of 0.2 may be considered substantive but small, an effect size of 0.5 may be considered a moderate effect, and an effect size of 0.8 may be considered a large effect size.

For the log-likelihood analysis, we aggregated the responses given by the respondents on their skills and capabilities into two effects: High = Extensive + Moderate + Yes, and Low = Some + None + No. High includes all respondents who rated their skills as high, extensive or moderate, and Low includes all respondents who rated their skills as low, some or none. A similar aggregation was used for questions related to specific skills identified by respondents. For example, the responses to questions related to using Microsoft Word, Excel or PowerPoint were aggregated into the category ‘reporting software’. Thus we derived the following six categories of aggregated responses:

-

Reporting Software = Word + Excel + PowerPoint

-

Analysis Software = GIS + Access + Statistical Software

-

Information and Communication Technology = E-mail + Internet + Social Media + Outreach

-

Management = Miradi + Opportunities + Contacts + Accolades

-

Leadership Skills = Lead + Participate + Confidence + Advice

-

Conservation Capacity = Promotion + Strength + Contribute + Improved Conservation

To assess differences across the programmes with respect to performance of fellows and the comparison group, we aggregated all items for analysis into 2 × 2 contingency tables. There are several potential approaches to the analysis of such contingency tables; we employed the odds-ratio approach, which is widely used in medicine to compare the effect of treatment on an outcome (Bland & Altman, Reference Bland and Altman2000; Szumilas, Reference Szumilas2010). In our case the treatment tested was usually whether someone was part of one of the five MENTOR programmes or not, but we also viewed age and gender of fellows as treatments.

Results

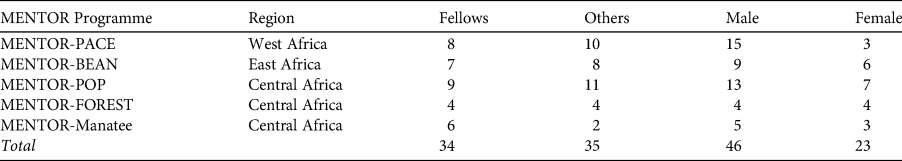

A total of 69 individuals were interviewed across all five programmes (Table 4): 34 were MENTOR fellows, and the remaining 35 were stakeholders associated with the programmes (mentors, lecturers and representatives of participating institutions). The opinions and perceptions expressed during informant interviews and online surveys suggests an overall positive view of the MENTOR programmes. All five programmes were considered as having successfully designed and implemented multidisciplinary activities that helped the cadre of professionals acquire new skills and expertise for advancing conservation. Key findings from the interviews and surveys as they relate to strategic relevance and design, effectiveness and impact, and sustainability of the programmes are presented below.

Table 4 Demographics of the 69 survey participants.

Strategic relevance and design

The evaluation confirmed the pervasive lack of adequate professional capacity (both in government and non-government agencies) to tackle threats facing the target species and associated ecosystems as a valid rationale for the programmes. Although there are important efforts already underway in the region to protect wildlife (e.g. protected area management, transboundary conservation and education), it was noted that a cadre of trained professionals working in a multidisciplinary team provides an additional dimension to the capacity and leadership needed. The focus on species of importance at global, regional and national levels across multiple countries was highlighted as critical for anchoring MENTOR-Manatee, MENTOR-PACE and MENTOR-POP. On the other hand, MENTOR-BEAN and MENTOR-FOREST were focused on knowledge and skills needed to mitigate threats from wildlife exploitation for bushmeat, and negative effects of extractive industries on wildlife and forests. It was noted, however, that the training had limited focus on key issues such as social science methods and anthropological principles that are critical for addressing these challenges.

Progress, effectiveness and impact

Although each MENTOR programme was independently designed and implemented, we found that they were consistent in their emphasis on combining academic training, experiential learning and mentoring for the team of aspiring conservation leaders. In addition to new skills and competences, the evaluation established that each programme created opportunities for fellows to gain real-time experience working as a team on complex conservation challenges. In some cases, fellows were able to apply their newly acquired knowledge on various activities, such as designing and implementing intervention and outreach programmes, and participating in technical workshops and international conferences. We also found that for all five programmes, instructors and mentors played an important role in helping the fellows establish and expand their professional networks.

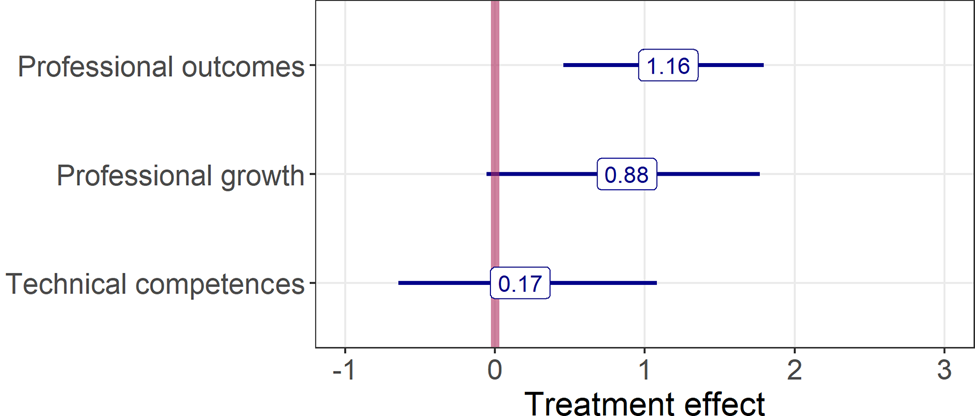

All participating fellows confirmed they acquired new skills and knowledge, and that their professional development was positively affected by participation in the programme. In comparison to non-fellows, we found a large treatment effect for professional growth (effect size 0.88) and professional outcomes (effect size 1.16), although we can rule out sampling error only for professional outcomes (Fig. 1). There was a modest treatment effect of 0.17 for technical competences, although further examination of the results showed that only competence in adaptive management (Miradi, which was a cornerstone of the MENTOR programmes) was a genuine effect.

Fig. 1 Normalized mean response and range of values, expressed as standard deviations, for the three major outcome categories of the MENTOR programmes. Where the range of treatment effects includes zero the possibility that the positive effect of training is a statistical artifact cannot be excluded at conventional levels of statistical certainty.

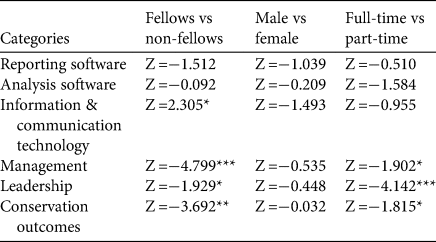

Fellows rated themselves significantly better than did the comparison group in soft or people skills, but not in technical skills (Table 5). The age and gender of the fellows had no significant effect on how they rated themselves, although several attributes were close to significance (P < 0.1). Although the programmes were established at different times, this had no consequence on self-assessment by fellows. However, fellows on programmes that were full-time rated themselves higher than those on programmes that were part-time.

Table 5 Significance of log odds-ratio for effect of MENTOR Programmes. Participant responses were aggregated in six categories and effects compared across three treatments: fellows vs non-fellows, male vs female, full-time vs part-time programmes.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Fellows attributed changes in their capabilities, confidence and professionalism to the overall programme approach, and most believed they had an important impact in conservation as a result. From the interviews, MENTOR-PACE fellows suggested the programme was highly valued by all despite differences in their professional development. As one fellow put it: ‘The most valuable part of the programme was the opportunity to work with professionals who have full-time jobs, and building their capacity while they are in their jobs also gave them direct on-the-job benefits.’

Sustainability

We found that the multidisciplinary focus, approach to mentoring and team building, and institutional context for each of the programmes inspired fellows to develop professional networks and relationships that are likely to endure. In the words of one MENTOR-POP fellow: ‘It was an unforgettable experience and has opened many more opportunities for my career development.’

For some programmes, we noted that the networks created are likely to provide long-term support for conservation of the targeted species and/or ecosystems. For example, MENTOR-PACE created a virtual network for lecturers, advisors, mentors, experts and fellows to continue knowledge exchange on conservation of the western chimpanzee in Liberia and Sierra Leone. MENTOR-POP mobilized diverse partners and organizations that contributed to the programme through teaching, internship opportunities, mentoring, workshops and site visits. Several of the training modules from MENTOR-BEAN have been incorporated into curricula at the University of Nairobi in Kenya and the Pasiansi Wildlife Training Institute in Tanzania. Similar steps were taken for MENTOR-FOREST, with the training modules developed further for a Master's degree.

With regard to programme outcomes, we identified some unintended consequences that have implications for their sustainability. Firstly, some MENTOR-PACE fellows started the programme with the approval of their employers but were eventually either seconded or left to take up new jobs elsewhere. As stated by one of the fellows: ‘I am now [a] seconded staff to the Wonegizi-Wologizi project funded by the West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change project implemented by Fauna & Flora International, and one of the African Ranger Awards winners.’ These types of change could not have been predicted as the employer's situation also changed during the course of the programme such that the original employer could not afford to have their employees away for large blocks of time; this seems particularly true of NGOs. Fellows sought alternative employment, often looking for positions they believed to be longer term, more secure and more sustainable.

Discussion

The MENTOR programmes were envisioned as a new model for developing capacity and leadership to tackle a wide range of issues surrounding the conservation of forests and wildlife in Africa, including the following: importance and management effectiveness of protected areas, illegal wildlife trade, commercial bushmeat exploitation, wildlife governance and law enforcement, extractive industries, agricultural commodity-driven deforestation, and management of the human–wildlife interface (e.g. conflicts, zoonoses). Findings from the evaluation suggests that the design and implementation of all five programmes were consistent with this vision. Exposure to these complex challenges facing conservation is critical for helping aspiring leaders formulate realistic visions and practical solutions (Deitz et al., Reference Dietz, Aviram, Bickford, Douthwaite, Goodstine and Izursa2004). This was reflected in some specific tasks undertaken by fellows, such as tackling bushmeat trade in Eastern Africa (MENTOR-BEAN), re-writing the Forest Code in Gabon (MENTOR-FOREST), developing an action plan for conservation of western chimpanzees (MENTOR-PACE), and tackling illegal trade of pangolins (MENTOR-POP).

The programme approach of combining academic training, experiential learning, team building and mentoring had significant impact on professional outcomes for the participating fellows. Although independently designed and implemented, each programme created a focused and multidisciplinary learning environment in which mentors could provide substantive guidance for long-term career development and serve as role models for the fellows. In this context, mentorship was used to transfer knowledge associated with specific disciplines to developing professionals (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Ryan, Campa and Smith2005), and as a pedagogical tool to integrate theory and practice (Arnesson & Albinsson, Reference Arnesson and Albinsson2017).

Beyond the knowledge and understanding of the issues and challenges for conservation of the target species and ecosystems, the fellows acquired valuable soft and people skills to help strengthen their leadership capabilities. Bruyere (Reference Bruyere2015) suggested that conservation leadership should include skills to establish a vision, define and integrate values, manage conflict, build partnerships and manage adaptively. Complementing technical competences with interpersonal skills is key to achieving high-quality leadership for conservation (Englefield et al., Reference Englefield, Black, Copsey and Knight2019), and competences related to interpersonal leadership skills are key for effectiveness, particularly in building trust (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nasirwa, Carter, Farmer, Appleton and Arinaitwe2017). Such leadership skills can play a critical role, for example, in the implementation of wildlife governance and the capacity of current governance structures to capture and distribute economic benefits from wildlife (Muchapondwa & Stage, Reference Muchapondwa and Stage2015).

Although each of the programmes focused on challenges linked to specific species and ecosystems, the evaluation suggests that the multidisciplinary approach allowed fellows to understand the importance of inclusiveness in seeking solutions for conservation of wildlife in Africa. For example, fellows were exposed to discourse on the practicality of contemporary conservation concepts such as community-based natural resource management, payments for ecosystem services, landscape approaches and biodiversity mainstreaming. Drawing on their own diverse backgrounds (e.g. in law, anthropology, teaching, public administration, urban planning, tourism, wildlife, forestry), fellows were well-positioned to understand the importance of multi-stakeholder engagement and pluralism in wildlife conservation (Green et al., Reference Green, Armstrong, Bogan, Darling, Kross and Rochman2015), and embrace systems thinking in advancing solutions (Black et al., Reference Black, Groombridge and Jones2011). Academic and non-academic institutions and organizations across Africa are exploring such approaches to conduct multidisciplinary training and research for managing challenges such as the outbreak of infectious diseases (Rwego et al., Reference Rwego, Babalobi, Musotsi, Nzietchueng, Tiambo and Kabasa2016).

As demand for conservation leaders increases, there is need to expand professional training across the continent beyond traditional pedagogical systems. The skills and competences needed cannot be met by a one-size-fits-all approach (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nasirwa, Carter, Farmer, Appleton and Arinaitwe2017). What the MENTOR programme has demonstrated is the value of structuring capacity and leadership development around specific challenges that reflect the realities of conservation across Africa. Fellows not only acquired new skills and expertise to advance their careers, but also developed potentially enduring relationships. Although it will take time for the achievements to translate into direct benefits for the targeted species and ecosystems, we believe the overall approach shows promise for developing African conservation leaders. The fact that training modules for some of the MENTOR programmes have been incorporated into curricula at various institutions of higher learning suggests the strategic importance of this approach.

To continue expanding the MENTOR model, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is currently supporting a MENTOR-Fish programme in Gabon and a MENTOR-Bushmeat programme for Central Africa. Important shortcomings of the programmes, such as failure to achieve gender balance, and limited integration of social science research methods and anthropological principles in the curricula, will be addressed. This will further strengthen the fellows' understanding of cultural diversity and their abilities in data collection.

Based on the experiences and lessons from this assessment of linking training and mentorship for leadership development, we conclude that: (1) Aspiring conservation leaders can acquire valuable knowledge, technical skills and competences through professional training programmes that are designed to address specific challenges facing species and ecosystems across the continent. (2) The unique MENTOR approach of combining technical training and mentorship could help to professionalize the wildlife conservation sector, especially so that the governments and non-governmental entities can benefit from more and better-trained leaders. (3) MENTOR-type programmes could harness and amplify the strengths of fellows by keeping them engaged as a team upon completion of a programme. This will create opportunities for them to network, maintain focus on specific conservation issues and become increasingly influential.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all who participated in the interviews and surveys, including representatives of the MENTOR partner institutions. Contributions by DK and MM were funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. AN and SO were independent consultants contracted to provide training for Njala University staff. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the institutions represented. We dedicate this paper to the memory of Martin Hega, who was a major inspiration behind the MENTOR-POP programme.

Author contributions

Study design and coordination: IA-B, AL, MIB; interviews, surveys: JJ, PJK, ES-M, AN, SO; PFYT; statistical analyses: DK, MM, RW; writing, revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

NG is a full-time employee of U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service who contributed background information on the MENTOR programmes. We therefore see no grounds for conflict.

Ethical standards

The informant interviews and online surveys abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.