No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

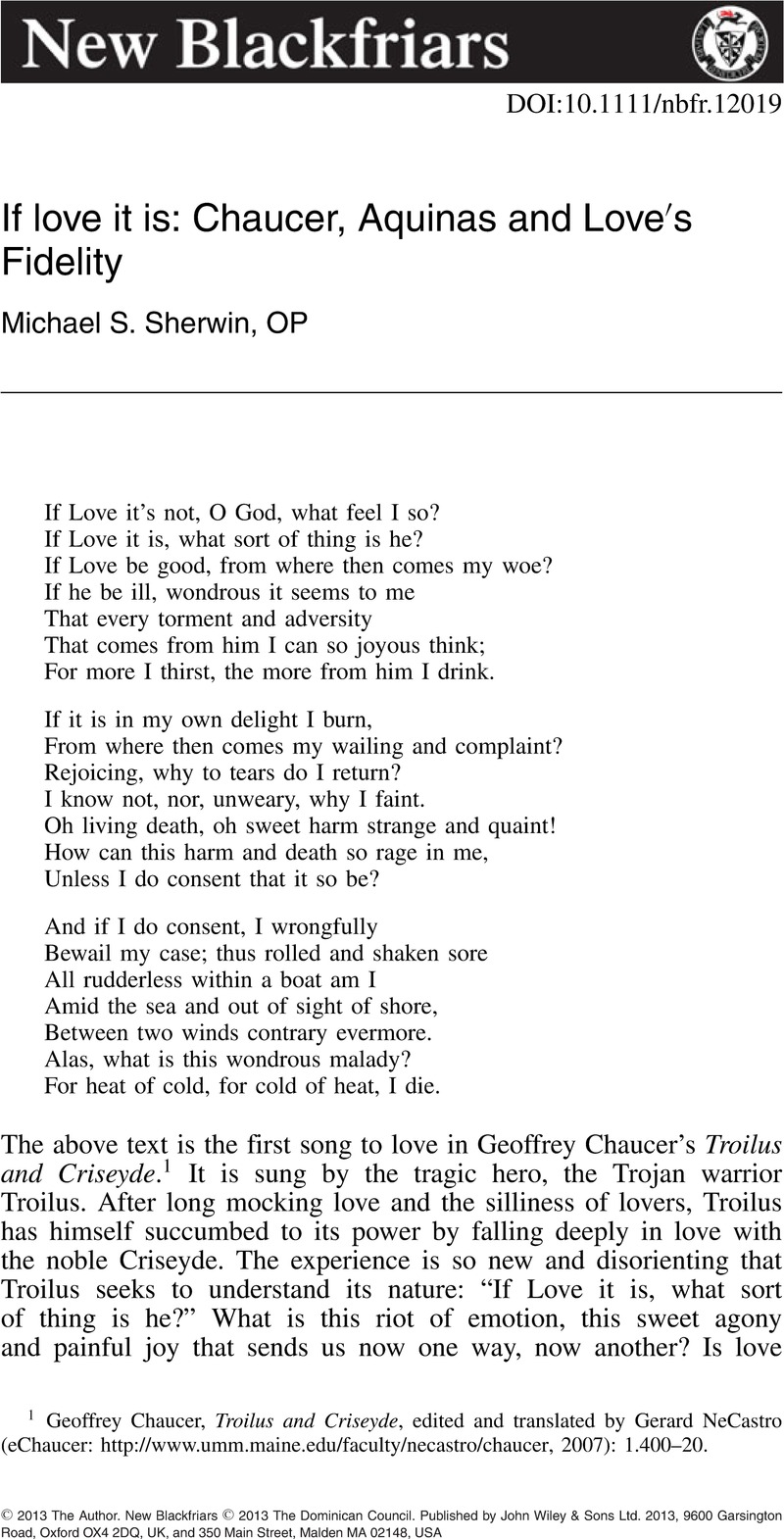

If love it is: Chaucer, Aquinas and Love′s Fidelity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2024

Abstract

- Type

- Original Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2013 The Author. New Blackfriars © 2013 The Dominican Council

References

1 Geoffrey Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde, edited and translated by Gerard NeCastro (eChaucer: http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer, 2007): 1.400–20.

2 See Saunders, Corinne, “Love and the Making of the Self,” in A Concise Companion to Chaucer, edited by Saunders, Corinne (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), 145Google Scholar.

3 See Andrew Lynch, “Love in Wartime: Troilus and Criseyde as Trojan History,” in A Concise Companion to Chaucer, 113–133.

4 Homer, Iliad 24.257 and Scholia S-I24257a.

5 See Windeatt, Barry, Troilus and Criseyde, Oxford Guides to Chaucer (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), 37–137 and 279–88Google Scholar.

6 Saunders, “Love and the Making of the Self,” 139.

7 See Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 96–109.

8 Kittredge, George Lyman, Chaucer and His Poetry (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1915), 109Google Scholar. Windeatt offers perhaps the most balanced appraisal when he states that, “Chaucer's insight into character invites comparison with the modern novel in its sustained attention to inward feeling and motive” (Windeatt, Barry, “Introduction,” in Troilus and Criseyde [London: Penguin Books, 2003], xvGoogle Scholar).

9 Bellah, Robert N., et al., Habits of the Heart (Berkeley: University of California, 1985), 3–8Google Scholar.

10 Dillard, Annie, The Maytrees (New York: Harper Collins, 2007), 127–29Google Scholar.

11 Ibid., 127.

12 Ibid., 128.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., 129.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid., 130.

20 Summa theologiae (ST) I 20.1 ad 1; ST I 80.2 ad 3.

21 ST I 81.3 ad 2 and Aristotle Politics 1.2 (1254b2).

22 See Aristotle Metaphysics 12 (1072a26–28 and 1072b3) and Physics 8.6 (258b26–259a9).

23 See ST I 60.1, ST I-II 23.4, ST I-II 25.2, ST I-II 26.1 and 2, ST I-II 36.2.

24 See Spicq, Ceslas, Theological Lexicon of the New Testament, translated and edited by Ernest, James D. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), vol. 2, 99–106Google Scholar.

25 ST I-II 26.2: “prima ergo immutatio appetitus ab appetibili vocatur amor, qui nihil est aliud quam complacentia appetibilis.”

26 ST I-II 26.1.

27 See ST I-II 25.2, ST I-II 26.4 and also ST II-II 27.2.

28 Pieper, Josef, About Love, translated by Richard, and Clara Winston, (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1972), 22Google Scholar. See ST II-II 25.7 and ST I 20.2.

29 ST II-II 27.2.

30 ST I-II 26.3.

31 ST I-II 26.1.

32 ST I-II 57.4, ST I-II 19.3 ad 2 and ST II-II 47.1 ad 1.

33 ST I-II 63.3. See also ST II-II 47.14 ad 3.

34 ST I-II, 65.3 ad 2. See also De virtutibus, 1.10 ad 16.

35 Weis, Karin, “Conclusion: The Nature and Interrelations of Theories of Love,” in Sternberg, Robert J. and Weis, Karin, eds., The New Psychology of Love (New Havel: Yale University Press, 2006), 313Google Scholar.

36 Ibid., 313, 314, 320.

37 Ibid., 320.

38 Ibid., 323.

39 Ibid., 320.

40 Lewis, Thomas, Amini, Fari, and Lannon, Richard, A General Theory of Love (New York: Vintage Books, 2001), 11Google Scholar.

41 Lewis, Amini and Lannon describe these features as “limbic resonance,” “limbic regulation” and “limbic revision” respectively (ibid., 63, 85, and 144). Since, however, in the standard tripartite theory of the brain adopted by these authors, “limbic” simply refers to the part of the brain that controls emotion, I have replaced “limbic” with “emotional.”

42 Kugiumutzakis, Giannis, Kokkinaki, Theano, Makrodimitraki, Maria, and Vitalaki, Elena, “Emotions in Early Mimesis” in Emotional Development: Recent Research Advances, edited by Nadel, Jacqueline and Muir, Darwin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 161–82Google Scholar. See also Ekman, Paul, “An Argument for Basic Emotions,” Cognition and Emotion 6 (1992): 169–200CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

43 Lewis, General Theory of Love, 63.

44 Ibid., 64.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid., 65.

47 Ibid., 85.

48 Studies of toddlers’ reactions to their mothers’ facial expressions and other emotional indicators in the “visual cliff” experiments are especially telling. See Lewis, General Theory of Love, 60–2.

49 See Lewis, General Theory of Love, 140–64.

50 Ibid., 86 (emphasis in the original).

51 Ibid., 144.

52 Ibid.

53 See, for example, Fiese, Barbara H., Foley, K. P., and Spagnola, Mary, “Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child well-being and family identity,” New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development 111 (2006): 67-90CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Juslin, Patrik and Sloboda, John A., eds., Music and Emotion: Theory and Research (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Matravers, Derek, “Recent Philosophical Work on the Connection between Music and the Emotions,” Music Analysis 29 (2010): 8–18CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Koch, Sabine C. and Braüninger, Iris, “International Dance/Movement Therapy Research: Recent Findings and Perspectives,” American Journal of Dance Therapy 28 (2006): 127–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Winters, Allison F., “Emotion, Embodiment, and Mirror Neurons in Dance/Movement Therapy: A Connection Across Disciplines,” American Journal of Dance Therapy 30 (2008): 84–105CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

54 Gioia, Ted, Work Songs (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 247 and 249Google Scholar.

55 See Gioia, , Work Songs and Ted Gioia, Healing Songs (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006)Google Scholar.

56 There is in Chaucer's account a subtle criticism of the hidden character of Troilus and Criseyde's relationship. See Morgan, Gerald, “The Ending of ‘Troilus and Criseyde’,” The Modern Language Review 77 (1982), 268CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

57 Homer, Iliad 6.455.

58 The following description of the context of Chaucer's life and the composition of his Troilus is drawn from Brown, Peter, Geoffrey Chaucer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1–63Google Scholar, Robertson, D. W. Jr., “The Probable Date and Purpose of Chaucer's Troilus,” Medievalia et Humanistica 13 (1985): 143–171Google Scholar and Federico, Sylvia, New Troy: Fantasies of Empire in the Late Middle Ages (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003Google Scholar).

59 Hatcher, John, “England in the Aftermath of the Black Death,” Past and Present 144 (1994): 3–35CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 Robertson, “Probable Date and Purpose of Chaucer's Troilus,” 151–52.

61 Lynch, “Love in Wartime,” 113–15, and 125–26, Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 7–8.

62 Chaucer, Geoffrey, Boece in The Riverside Chaucer, 3rd edition, edited by Benson, Larry D. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 395–469Google Scholar. See Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 9.

63 Wetherbee, Winthrop, “The Consolation and medieval literature,” in Cambridge Companion to Boethius, edited by Marenbon, John (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 279–302CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

64 See Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 96–109.

65 Boethius, in the Consolation of Philosophy (book 3, prose 9), after speaking of “mendacis formam felicitatis,” which Chaucer translates as “fals welefulnesse,” explains what he means by contrasting true and perfect things with false and imperfect things, using the appositive expression “falsum imperfectumque,” which Chaucer translates as “false and inparfit.” Then, in the following chapter (b. 3, pr. 10), Boethius describes it as an imperfect happiness founded upon a fragile good: “quaedam boni fragilis imperfecta felicitas,” which Chaucer translates as “a blisfulnesse that be freel and veyn and inparfyt.” Following Boethius’ usage, therefore, “fals” for Chaucer in this context means “inparfit” and “freel.”

66 Boethius, , The Consolation of Philosophy, translated with introduction and explanatory notes by Walsh, P. G. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), book 4, metrum 6, 94Google Scholar.

67 See Boethius, Consolation, b. 4, especially metra 1 and 7, 72 and 96.

68 Dante, Paradiso 20.67–69. See Wheeler, Bonnie, “Dante, Chaucer, and the Ending of ‘Troilus and Criseyde’,” Philological Quarterly 61 (1982): 110Google Scholar.

69 Dante, Paradiso 22.133. See Morgan, “The Ending of Troilus,” 264 and Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 209–11.

70 Morgan, “The Ending of Troilus,” 264.

71 Chaucer describes his “little book” as a “little tragedy,” and prays “May God yet send your maker power, before he die, to use his pen in some comedy!” (5.1786–8). This prayer is speedily answered, because it is shortly after these lines that Chaucer recounts Troilus’ ascent into heaven. See Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 159 and 178. On the longstanding controversies concerning the religious ending of Troilus, see Morgan, “The Ending of Troilus,” 257–71, Windeatt, “Introduction,” xlv-xlviii, Windeatt, Troilus and Criseyde, 103–107, 231–34 and Steadman, John M., Disembodied Laughter: Troilus and the Apotheosis Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972)Google Scholar.

72 There is also the mysterious music that is only heard in silence, whereby God's presence, especially in the communal adoration of the Eucharist, quietly heals and shapes our emotions, deepening our love for him and for others. Thomas Lewis and his colleagues describe therapy as the healing act of “sitting in a room with another person for hours at a time with no purpose in mind but attending” (Lewis, General Theory of Love, 65). If such attending is healing on the natural human level, how much more so when the one in whose presence we are attending is Christ himself, present in the Eucharist?