For most historians, William Wilberforce is not immediately associated with the history of capital punishment, at least not beyond his occasional efforts to solicit mercy for individuals sentenced to death, and his distinctly subaltern role in the decisive early nineteenth century parliamentary debates over the abolition of the death penalty in England.Footnote 1 Most scholars concern themselves with the first of the two “great objects” of which, in a diary entry for October 28, 1787, Wilberforce declared that “God Almighty has set before me … the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.”Footnote 2 That concern is easily justified: the abolition of the slave trade quickly became the central preoccupation of Wilberforce's public life, and its implications were of global significance.Footnote 3 His second professed mission of 1787 onwards—to help launch and sustain the Society for Giving Effect to His Majesty's Proclamation against Vice and Immorality—has inspired a smaller, although no less rich, body of scholarship.Footnote 4 Our broad perspective on Wilberforce's public life remains that which was first laid down half a century ago, and which has subsequently been reinforced by historians of gender such as Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall. Wilberforce and his associates are principally seen as the progenitors of nineteenth century moral earnestness and spiritual idealism, as well as the feminine ideal of “the Angel in the House.” They were, as Ford K. Brown suggested in 1961, the “Fathers of the Victorians.”Footnote 5

In fact, capital punishment greatly concerned Wilberforce during the earliest phases of his public career. This article explores the immediate contexts of two of his earliest public efforts: his failed and largely forgotten “Felons Anatomy” bill of 1786; and his cofounding of the Proclamation Society the year afterwards.Footnote 6 The first of these two proposals, which sought to impose the extraordinary stigma of postmortem dissection upon executed felons, puzzled at least one of Wilberforce's biographers, John Pollock, who attributed this “somewhat bizarre measure” to “Wilberforce's inexperience as a humanitarian”.Footnote 7 It might also seem strange to those historians who see this era as being distinguished by the emergence of a powerfully humanitarian, self-consciously “sympathetic” mindset among England's propertied elites: a mindset of which Wilberforce has generally been taken to have been a principal advocate and architect.Footnote 8 Such historians have argued that a more and more “feeling” attitude toward the sufferings endured by various classes of humanity—not only of slaves overseas, but of convicted criminals at home—made the use of capital punishment less and less acceptable, as well as providing a coherent rationale for that growing use of imprisonment that characterized late Hanoverian England.Footnote 9 Such views have been powerfully challenged by V.A.C. Gatrell in The Hanging Tree, a celebrated and wide-ranging study of the culture and workings of capital punishment in early nineteenth century England. Gatrell argues that such pressures as were exerted to save the lives of condemned criminals by Wilberforce and other ostentatiously “humanitarian” sorts were both socially selective (they usually only championed prisoners whose social-economic status and professed mentalities were akin to their own) and far too small-scale and intermittent to make anything but the tiniest dent in the vast number of people who were being hanged during the last years of “the Bloody Code.”Footnote 10

The following analysis presents evidence both to support and to qualify both perspectives.Footnote 11 By comparison with Gatrell, it will be argued here, first, that in London at least, far more people were being hanged during the 1780s than during the post-Napoleonic era. Second, and in contrast to Gatrell's portrait of an unremittingly severe-minded ruling elite, ready and willing to enforce “the Bloody Code” until the eve of its abolition in the 1830s, this article will demonstrate that, as early as the 1780s, some of the nation's leading statesmen—particularly the prime minister, William Pitt the Younger—actively sought practical alternatives to an overly extensive use of the gallows.Footnote 12 To historians who see the 1780s as an era of rising sympathetic and humanitarian sentiments, however, this article also presents a qualifying perspective. Although younger statesman such as Pitt and his friend Wilberforce wanted to reduce that intensive use of the gallows which characterized this first decade of their public lives, they were also obliged to contend with powerful arguments in favor of a policy of maximum severity. That policy, substantively driven and sustained by an “older” generation of political and legal officials, could nevertheless be persuasively rationalized in the immediate context of the times. England experienced a crime wave of unprecedented scale and persistence following the end of the war with America; and until almost the end of the decade, Pitt's government repeatedly failed to find effective alternatives, in the realms of punishment and policing alike, to such a heavy a reliance on the gallows.

This persistent crisis of criminality and execution levels provided the common and compelling—but also temporally specific—impetus to both Wilberforce's “Felons Anatomy bill” of 1786 and his adoption of the Proclamation Society the year after. Both measures were intended to serve other urgently felt public purposes as well. The particular support that they enjoyed from Pitt's government, however, derived first and foremost from the prospect they afforded of reducing the wide-scale imposition of capital punishment. They were meant to serve a basic and (for some, but only some) urgently felt humanitarian aim of the moment: to find a means whereby the large numbers of people being sent to the gallows might permanently be reduced to levels that were more in accord with a growing body of moral and intellectual objections to capital punishment from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. As such, they essentially reflected the committed public humanitarian whom Wilberforce was in the process of becoming. Close analysis of these two measures and their immediate contexts sheds light on some of the more unusual, unexpected, and (sometimes) seemingly contradictory dimensions of humanely inspired efforts to restrict the use of capital punishment in late eighteenth century England.

Execution, Transportation, and Policing in London, 1782–85

Both the timing of Wilberforce's two initiatives and the support they enjoyed from Pitt's government stemmed from the comprehensive and transparent failure of that government's established policies on criminal law. Pitt and his home secretary, Lord Sydney, had helped to establish those policies during the short-lived ministry of the Earl of Shelburne (July 1782–February 1783), in which Pitt had served as chancellor of the exchequer and Sydney had (again) been home secretary.Footnote 13 The question of how best to deal with the rising tide of convicted criminality was an unusually urgent one in the years immediately following the end of the war with America. Recurrent experience over the previous century had demonstrated that crime levels seemed to increase dramatically during the severe social-economic dislocations that followed the end of war. Whether or not that was truly the case (some historians have doubts), convictions for crime certainly surged after each war ended.Footnote 14 By the early 1780s, however, the only widely accepted secondary punishment for prisoners convicted of capital crimes, transportation to the American colonies, had been in abeyance since the outbreak of war in 1775. Imprisonment at hard labor on board prison hulks moored in the river Thames, implemented in 1776, had soon proven to be a controversial and generally unacceptable alternative: so much so that, even though the Penitentiary Act of 1779 promised the construction of a pair of buildings in which the secure and appropriately disciplined confinement of prisoners might at last be achieved on an extensive scale, it could not be passed through parliament without also promising the resumption of transportation for much the same categories of convicts as had been subject to transportation before 1775.Footnote 15

Such enthusiasm as had once prevailed for the penitentiary project, in government circles at any rate, was ebbing by the end of the war. The general anxiety over the state of public finance that dominated parliamentary politics from the 1780s onwards severely curbed any appetite for a controversial penal experiment as expensive as the penitentiaries promised to become.Footnote 16 The project's supervisors estimated the minimum cost for constructing the two buildings proposed under the Penitentiary Act to be almost £150,000, a sum that comprised nearly 60% of all nonmilitary expenditure (outside the Civil List) for 1782.Footnote 17 At the end of September 1782, Shelburne's government informed the project's supervisors “that new measures were about to be taken with respect to felons, which made the hastening the Penitentiary Houses less necessary,” a statement that proved to be a politely muted prelude to a refusal to make any further funds available.Footnote 18 The most direct pressure on government to persist with a national penitentiary scheme was further reduced when the project's two most active proponents, Sir Charles Bunbury and Sir Gilbert Elliott, both lost their seats in the general election of 1784.Footnote 19

Shelburne's government now gave priority to the two most important punishments that had long since been imposed upon the most serious criminal offenders: execution and transportation overseas. In the same month that the penitentiary project was effectively cancelled, and in light of “the great number of robberies that have been lately committed, and attended with acts of great cruelty,” the government resolved (at least in London) “to grant no pardon or respite to any person convicted of such offenses, on any solicitation whatsoever.”Footnote 20 At the same time, the active search began for an appropriate new destination with which the full-scale transportation of Britain's convicts might be resumed.Footnote 21 Disillusion with the experience of the hulks had reinforced the preference of many officials, especially in metropolitan London, for sending the worst classes of convicts (next to those who were actually hanged) overseas.Footnote 22 From the early 1770s at least, Africa had been suggested as a more imposing destination than an America whose explosive social-economic growth over the course of the century had rendered it far too hospitable for transportation there to seem an appropriately severe fate for serious criminals.Footnote 23

Shelburne's government probably expected the unswerving imposition of executions to be only a temporary necessity. The principal strategy for reducing crime was to emphasize prevention in the first instance rather than any hope of reforming criminals through more effective modes of secondary punishment. “I was assured,” Shelburne later wrote, in recalling the cancellation of the penitentiary project, “that if the number of ale-houses could be lessened, the Vagrant Act enforced, and the general administration of justice as it stood invigorated, a great deal might be done without having recourse to any new institution.”Footnote 24 This change in direction was publicly announced in the king's speech at the opening of parliament in December 1782: “It were much to be wished that [theft and robbery] could be prevented in their infancy, by correcting the vices become prevalent in a most alarming degree.”Footnote 25

This was only the latest recrudescence of a long-established body of thinking as to how best to tackle crime. Throughout the eighteenth century (and long before), it was generally believed that the most effective means of preventing the worst sorts of crimes was to ensure that less serious offenses—petty thieving, drinking, gambling and sexual misconduct—were sternly dealt with when first they occurred. This stemmed from the belief that serious criminals were not “born” that way, and that poverty or any other environmental circumstances were neither rational motives nor excuses for criminality. The rise to pre-eminence of those modern perceptions lay almost a century in the future.Footnote 26 Rather, the capacity and inclination for the worst sorts of criminality grew within each individual offender by successive degrees of moral corruption. The boy who pilfered seemingly unimportant items and who grew accustomed to lying to mask his minor failings, if not immediately and unwaveringly corrected both morally and physically, grew into the youth who neglected his studies and other assigned duties, and developed a taste for such lax pursuits as gaming, drinking, and theater going. If still no intervention were made in these adolescent ill-courses, the youth might then became a man with a confirmed taste for those activities via persistent association with “bad company” (reprobate men and women of easy virtue) and would finally turn to robbery and burglary to sustain his corrupt lifestyle. This life's path, once embarked upon, was an ever-steepening downward slope. If not checked at some stage by an appropriately scaled degree of punishment, the boy who erred in only minor ways might become a man who ended his days on the gallows.Footnote 27 So hardened would he have become, in both inclinations and sensibility, that he would pass all points of reclamation and become fit for no worldly purpose other than to serve as an imposing example to those who remained redeemable.Footnote 28 The night before he was hanged for forgery in March 1784, John Lee reportedly wrote a letter in which he recalled his youthful susceptibility “not only [to] the follies, but even the vices of my companions” and counselled others against neglect of Christian belief.Footnote 29 Similarly Joseph Mayett, a soldier of the Napoleonic era, recounted an adolescence in which, having “done all that lay in my power to stifle the Convictions of Conscience,” he “went from bad to worse until almost everybody that knew me Cried out Shame upon me, for there was hardly any mischief done in the place but I had a hand in.” Finally, after a near-escape while stealing in an orchard, Mayett began “to tremble and Resolved to give out thieving, for I thought that though I had escaped Justice that time, if I still practised it would harden me more in it and bring me to the gallows at last, so I gave it up altogether.”Footnote 30

In a world in which both familial and political authority were still viewed in essentially Christian and patriarchal terms—and therefore as being fundamentally intertwined, and mutually reinforcing—the main responsibility for correcting errant tendencies lay first, among children and adolescents, with parents, masters, and mistresses; and subsequently, among adults, with magistrates. As far back as the late Middle Ages, the regulation of morals offenses had been a concern for royal law. Such concerns were intermittently revitalized in the early modern era, perhaps especially under the pressure of Puritan social reform movements,Footnote 31 and they enjoyed renewed periods of energy (as will be discussed in the last section of this article) in later Stuart and Hanoverian England in the form of “reformation of manners” movements. That a similarly revitalized commitment underpinned the Shelburne government's renunciation of the penitentiary project was clearly suggested, as has already been noted, in the king's speech to parliament in December 1782. It was even more explicitly spelled out in the preliminary draft of that speech:

But as it is to [be] wished that these Crimes [i.e., capital robberies] should be prevented rather than punished, I must earnestly recommend to your Consideration to revise such Laws as have been hitherto Made for the Discountenancing & suppressing those Vices, by which the Younger Part of the Lower Orders of People are often impelled to become dangerous instead of useful Members of Society: & likewise to consider of such regulations as may effectively control & deter those by whose seduction these unhappy People are generally led into habits dangerous to themselves, as well as detrimental to their Fellow Subjects.Footnote 32

This is exactly what Shelburne's home secretary asked London's magistrates to start doing one month after the government had informed the penitentiary's supervisors that their project was now “less necessary.”

On October 22, 1782 Thomas Townshend (the future Lord Sydney) sent a letter to the chairmen of the sessions of the peace for the county of Middlesex, the City of London, and St Margaret's Hill (in the county of Surrey). Lamenting “the frequent Robberies and Disorders of late committed in the Streets of London and Westminster,” which he attributed to the excessive number of gaming and drinking houses, Townshend ordered the magistrates to convene “frequent Petty Sessions … in their several Parishes” to ensure that “the High Constables and other proper Officers under their Direction” would more regularly and systematically “search for and apprehend Rogues, Vagabonds, idle and disorderly Persons, in order to their being dealt with according to Law; and likewise … proceed with Rigour against all Persons harbouring such Offenders, as against those who keep … Night-houses or Cellars, Tippling or common Gaming-houses, or who practice or encourage unlawful Gaming.”Footnote 33 These were duties with which magistrates, as well as the constables and other officers who served under them, had long been charged by law, and to which they were occasionally enjoined by government to devote greater attention.

Requiring unpaid magistrates to apply their energies to their prescribed tasks was one thing; ensuring that they did so was another, and to this end Townshend added a new requirement. All of “the said Justices in their respective Sessions” were now requested “to draw up in writing, from Time to Time, an Account of their Proceedings” and to transmit it to the home secretary for communication to the king, so that exemplary justices might be singled out and rewarded for their attention to their duties.Footnote 34 For the first time, government was attempting to apply a substantive “carrot” to an otherwise traditional-looking directive to local officials.Footnote 35 Resolutions were quickly passed in various sessional divisions of the metropolis, but there is little evidence to suggest that this brief flurry of magisterial enthusiasm was sustained much beyond the spring of 1783, when the chair of the Middlesex sessions transmitted an impressively detailed list of proceedings conducted by the rotation office in Whitechapel.Footnote 36

The idea of solving this problem by creating a body of salaried magistrates and constables for the metropolis—men who would, for the first time, be paid to perform the duties required of them—seems to have arisen as early as the spring of 1782, when David Wilmot, the industrious Middlesex JP in charge of the Shoreditch rotation office, submitted such a proposal for the City of Westminster and the County of Middlesex.Footnote 37 Three years later, a bill to that effect was in preparation under the authorship of lawyer John Reeves. A draft was ready by April 11, 1785, and word of the measure began to spread soon after.Footnote 38 Reeve's scheme moved far beyond Wilmot's original proposal, embracing not only Westminster and its suburbs (although not, as had Wilmot's, the rest of the county of Middlesex), but also the adjacent Cities of London (to the east) and Southwark (south of the river), as well as their suburbs.

The scope of the “Metropolitan Police Bill” that was finally introduced in the House of Commons on June 23, 1785, the furore with which it was greeted, and its withdrawal only six days later, have all been extensively studied by historians of English policing.Footnote 39 The ambitions of the measure that was finally presented were remarkable for its time. It proposed to expand the very definitions of policing activity in the metropolis, including regular street patrols of a sort that would ultimately be central to Robert Peel's Metropolitan Police Act of 1829; it also sought to wrest control over all of this much-enhanced activity away from traditional local authorities and to place it more firmly in the hands of the central government. As radical as all this was, however, it should nonetheless be remembered that the core impetus to the bill in the first place had been the government's particular desire to enhance the pursuit, prosecution, and punishment of noncapital crimes as a means to prevent the individual offender's descent into more serious criminality.Footnote 40 The Solicitor General, Archibald Macdonald, suggested as much in his remarks on presenting the bill to the Commons, in which he spoke of how “young children were initiated by the elder rogues, … and at length these wretches terminated their existence under the hands of the hangman, at 17 or 18 [years of age], though old and accomplished in the mysteries of their profession …”.Footnote 41 In this respect, the 1785 Police Bill was as much an expression of an older notion of preventative policing as of the more modern notion of preventing all crimes via a system of sustained patrolling and surveillance.

Equally importantly, Macdonald's opening remarks emphasized that this radically altered police force would ultimately provide the means by which to reduce an execution rate in London that had now reached horrifying new levels. The impact of the government's September 1782 policy of hanging, without exception, those convicted of “robberies … attended with acts of great cruelty” is readily apparent in Figure 1.Footnote 42 From 1760 to 1782, and with the exception of a few marked reversals, the proportion of people convicted of capital crimes at the Old Bailey who were actually executed appears to have been gradually declining.Footnote 43 These were years in which, as Randall McGowen and others have shown, the underlying intellectual and moral bases of capital punishment were being fundamentally challenged.Footnote 44 Between 1782 and 1787, however, there was a marked reversal in this apparent trend toward a reduced use of the gallows. Both the proportion of capital convicts put to death, and especially the absolute number of them, increased rapidly and dramatically.Footnote 45 By 1784, London newspapers were frequently lamenting both the scale of executions outside Newgate and the ineffective system of policing that apparently made them necessary.Footnote 46

Figure 1. Old Bailey executions, 1760–1810. Source: Execution and Pardon: Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey, 1730–1837. http://hcmc.uvic.ca/.

Pitt's government was not indifferent to such protests. In introducing the Police Bill, the solicitor general lamented “the crowds that every two or three months fell a sacrifice to the justice of their country, with whose weight, as he said, the gallows groaned; and yet the example was found ineffectual, for the evil was increasing.” This was a remarkable confession from one of the government's senior legal officials: a recognition that large-scale executions were obviously “ineffectual” as a deterrent; “that the present laws, and the mode of executing them now in use, were inadequate to” the reduction of crime in London; and “that extreme severity, instead of operating as a prevention to crimes, rather tended to inflame and promote them, by adding desperation to villainy.” Given “that severity would be ineffectual,” the only alternative was “to render detection certain and punishment, with a moderate degree of severity, unavoidable.” This fundamental policing task “would never be adequately and effectually performed, unless those to whom the performance was committed, were paid for their trouble”— that is, the hard-pressed magistrates of the metropolis. In this respect, the bill aimed not at “subverting the established system” of magisterial authority in London, but rather sought “to strengthen and support it.”Footnote 47

He might further have added that some such measure was now made doubly necessary because the principal alternative to hanging—transportation overseas—had not only remained unavailable on a scale large enough to meet the need for far longer than anyone had anticipated in September 1782, but also now appeared as though it would remain so longer still. Only three months before the Police Bill was introduced, the government's plans to establish a self-sustaining African convict settlement on the island of Lemaine in the river Gambia had seemed to be nearing completion. Then protests had erupted on the floor of the House of Commons, with members of the opposition seriously questioning both the morality and the practical effects of such a scheme.Footnote 48 In addition to disrupting valuable trading concerns in the region (no small consideration in itself, as two subsequent parliamentary committee reports made clear), the conditions in that part of the world were believed to be so harsh as to constitute an effective death sentence. As such, they violated both the spirit and the letter of the laws that prescribed transportation, not only as the main condition of pardon from sentence of death, but also (and perhaps especially) as a sentence in the first instance for less serious, noncapital crimes.Footnote 49 The portrait of Lemaine, painted in one newspaper account of the time, was unpromising in the extreme: “[T]he heat in the months of July and August is very great; and towards the equinox, they experience dreadful storms of thunder and lighting. The country on each side [of] the river is peopled by warlike negro nations, who sacrifice to their idol deities such white men as fall into their hands, and whose bodies they devour; which will prevent [the convicts] deserting from the place allotted for them.”Footnote 50

Some people thought that such conditions perfectly acceptable where the worst sorts of offenders were concerned. “To transport capital felons to Africa, who have received his Majesty's pardon is undoubtedly just,” The Times observed. On the other hand, “as it has ever been held a point of law that the order cannot increase punishments, sending persons convicted of [non-capital] larcenies to Africa, which is one high road to eternity, does not appear as consistent with the principles of the British constitution.”Footnote 51

The ensuing parliamentary committee produced its second and final report on July 28, 1785, recommending a more southerly, coastal region of Africa—Das Voltas—as a more promising site for a permanent, healthy, and affordable convict settlement: the only African site capable of such “Commercial and Political Benefits” as “may be deemed of sufficient Consequence to warrant the Expense inseparable from such an Undertaking,” while “at the same Time” restoring “Energy to the execution of the Law, and contribut[ing] to the interior Police of this Kingdom.”Footnote 52 But Das Voltas had not yet been properly surveyed, so while the government sent out an investigative expedition, the immediate prospects for the resumption of convict transportation were at an end for several months more, and perhaps longer. The almost simultaneous collapse of the government's two principal criminal justice strategies, coupled with persistently high levels of execution, set the stage for William Wilberforce's first major criminal law initiative.

The Felons Anatomy Bill of 1786

In May 1786, the young Wilberforce—like Pitt, he was still only twenty-six years old—had been an MP for six years. The previous winter, after several years' enjoyment of the pleasures of London with his hard-drinking friends, he had undergone a religious awakening, one that sounded not unlike the change-of-heart professed by Joseph Mayett. “I must awake to my dangerous state,” Wilberforce confided to his diary on Sunday, November 27, 1785, “and never be at rest 'till I have made my peace with God. My heart is so hard, my blindness so great, that I cannot get a due hatred of sin, though I see I am all corrupt, and blinded to the perception of spiritual things.”Footnote 53 It seems odd that so newly regenerate a man should have risen in the House of Commons, scarcely half a year later, to propose “a Bill to regulate the Disposal, after Execution, of the Bodies of Criminals condemned and executed for certain heinous Offenses therein to be mentioned.”Footnote 54

Until recently, Wilberforce's bill had gone almost entirely unnoticed by historians.Footnote 55 It is not noted in Ruth Richardson's celebrated study of the social and cultural background to the Anatomy Act of 1832, nor in any of the more recent accounts of that subject.Footnote 56 It certainly puzzles the one historian of criminal law who has noticed it.Footnote 57 During an era in which most historians are concerned with identifying the early stirrings of humane sentiment and enlightened thought, it seems decidedly peculiar, even perverse, that the leading evangelical of his age should champion so seemingly unfeeling a measure. The bill proposed to make the corpses of certain categories of executed felons more readily available for dissection by students of anatomy, specifically rapists, arsonists, burglars and (a nod here to the government's policy of September 1782) robbers when “the offence was accompanied with wounding, beating or other circumstances of amorality.”Footnote 58 In other words, it sought to expand upon the Murder Act of 1752 (25 Geo. II, c. 37), which had made the bodies of all those hanged for that crime available to the surgeons for postmortem dissection.Footnote 59 The mystery of the bill's apparently savage character seems only to be deepened by the subsequent addition to it of a more obviously humane clause, abolishing the burning at the stake of women convicted of treason.Footnote 60 The most detailed modern biography of Wilberforce altogether omits mention of it, perhaps from a sense of the awkwardness or embarrassment it might pose to the great man's reputation. John Pollock concluded that “Wilberforce's inexperience as a humanitarian had muddled him into linking separate causes” in this “somewhat bizarre” measure, echoing Leon Radzinowicz's earlier conclusion that the bill must surely demonstrate that Wilberforce's understanding of “the problem of punishment” was “as yet immature.”Footnote 61

The Felons Anatomy Bill did have ultimately humane intentions, but we must explore its various contemporary contexts if we are better to grasp the character and extent of that “humanity.” Three such contexts need to be considered. First, although the postmortem dissection of convicted criminals was generally regarded with horror by the public at large, the plentiful supply of corpses for anatomical study was ultimately meant to ensure that surgery, an invariably agonizing ordeal in an era before the availability of effective anesthetics, could be performed as swiftly as possible so as to minimize the time in which any patient was kept under the knife.Footnote 62 Second, and although Wilberforce himself by no means concurred in such views, we should at least be aware that the mid-1780s was an era in which arguments for maximum severity in the application of the death penalty were advocated—and, for a time, actively put into force—in a number of influential public circles. Third and finally, we need to appreciate that Wilberforce's bill addressed itself to only a specifically defined body of criminal offenders, most notably those convicted of burglary.

The Needs of Anatomists

The surgical dimension provided the most obvious impetus for the bill. Wilberforce sat in the Commons as one of two MPs for his home county of Yorkshire. One of his close friends there was William Hey, an eminent surgeon in Leeds, who in May 1785 appears to have proposed the idea to both Wilberforce and Walter Stanhope, the Member for Kingston-upon-Hull.Footnote 63 “Though the knowledge of Anatomy is absolutely necessary to the welfare of mankind,” Hey wrote Stanhope, “yet there is in this kingdom no legal provision for the study of it.” The result, familiar to readers of Ruth Richardson, was a horrible trade in grave robbing to supply demand, a practice made worse still in that many of the stolen corpses arrived in so desiccated a state as to be dangerously infectious. “These and other considerations,” Hey continued, “induce me to think that it would be a proper plan to deliver up the bodies of all executed criminals to the Teachers of Anatomy. Such bodies are the most fit for anatomical investigation, as the subjects generally die in health, the bodies are sound and the parts distinct.” Nor should convicted felons expect any better a fate, thought Hey: “Why should not those be made to serve a valuable purpose when dead who were an universal nuisance when living?” Local, provincial interests played an important role as well. Because the Old Bailey conducted trials eight times per year, Hey noted, London surgeons enjoyed reasonably regular access to the fresh corpses of convicted murderers. By comparison, given that trials for felonies in the counties took place only twice a year at the assizes, provincial surgeons were far worse off. In truth, they really only had such access once a year: “The weather is too hot from April to August,” Hey maintained, “and all the criminals suffer in this part of the year, except those who are condemned for murder at the Spring Assizes, which usually are held in March.” Murderers tried and executed at the summer assizes were likely, after several months' confinement prior to trial, to have become too physically decrepit to provide the surgeons with a useful anatomical subject.Footnote 64

Hey was quite wrong to believe that London benefitted uniquely under the Murder Act of 1752. The need for anatomical subjects was as urgently felt in the capital as elsewhere. Historians of anatomy, from Richardson onwards, have assumed that the Murder Act increased the supply of corpses available to anatomy schools but that the demand for bodies from a rapidly expanding medical profession simply continued to outstrip supply. In fact, although no provision of the Act had specifically stated that anatomization would now be restricted to only the bodies of convicted murders, both the internal logic of the Act—to ensure that a “peculiar mark of infamy may be added to the punishment of death” where murder was concerned (25 Geo II, c.37, s.1)—and subsequent practice ensured that just such a restriction ensued. After 1752, about eleven more people convicted at the Old Bailey of a crime other than murder were turned over to the surgeons for postmortem dissection.Footnote 65 The number of Old Bailey felons received by the surgeons had averaged five or six per year during the 1730s, a figure that was already considerably lower than the ten bodies per annum that had been promised to London's surgeons since the late seventeenth century.Footnote 66 During the dozen years preceding the Murder Act, the number had already fallen to only one or two per year (and no one at all appears to have been given to the surgeons in 1744–46 and 1749). The yearly averages following passage of the Murder Act in 1752 were certainly an improvement over this: three to four per year for the remainder of the 1750s, but this fell to only two to three in the 1760s and 1770s, and the six-and-a-half years immediately preceding Wilberforce's bill were positively disastrous for the surgeons. Despite extraordinarily high levels of conviction for other violent crimes at the Old Bailey during the first half of the 1780s, murder convictions yielded an average of only one body per year for the London surgeons.Footnote 67 In short, far from assuring a permanent and substantial supply of corpses for anatomical study, the practical effect of the Murder Act had been to reduce the available number of bodies far below that which the surgeons had supposedly been assured before 1752, a number that had gone unrevised for almost a century beforehand.Footnote 68

Under these circumstances, it can be no surprise that grave robbing, an activity more famously associated with the early nineteenth century, was already becoming a problem in London by the 1780s, and was therefore one of the impetuses for Wilberforce's Felons Anatomy Bill. In presenting the measure to the Commons, Wilberforce followed Hey in invoking “the extreme difficulty surgeons experience in procuring bodies for dissection, and the shocking custom of digging them up after burial … frequently in such a state … that the great end of dissection was foiled,” and went on to suggest that “For these reasons, and a variety of others which could be urged, if necessary, [he] presumed there could be no objection to his motion.”Footnote 69 Grave robbing had recently provoked a scandal in London. In May 1785 a “surgeon of eminence” and the master of a workhouse had been jointly tried at King's Bench for “conspiracy in conveying away dead bodies, for the purpose of dissection.” Despite the surgeon's pleas of “the benefits which might accrue to society from the accurate knowledge of anatomy, which could be only thus obtained,” each was fined £10.Footnote 70 Another such case would come before the same court only three years later, and the issue would only provoke more and more public outrage until it was ultimately resolved by the Anatomy Act of 1832 (2 & 3 Will. IV, c.75), which abolished postmortem dissection of convicted murderers, and instead sought to ensure that surgeons would henceforth receive the unclaimed bodies of people who died in the parish workhouse.

But what of the “variety of other” reasons for the bill of which Wilberforce spoke when introducing it? The support that the bill received from government indicates that this was no mere “local” measure, despite the obvious hand of Yorkshire MPs in its initial moving. Henry Dundas, Pitt's right-hand man in the Commons (and a future home secretary), emphasized that the bill would be carefully framed “in order to avoid destroying the effect [that] the sentencing the bodies of malefactors to be anatomized after execution had upon the prejudices of mankind, considered as punishment for crimes.” More striking was the reported aid of Pitt himself “in drawing up the motion” for the bill, as well as home secretary Sydney's advocacy of it in the House of Lords following its passage by the Commons.Footnote 71 The hand of government was especially apparent in the withdrawal of the first draft of the bill (presented to the House on June 22) on the grounds of its not having been “properly prepared” and the subsequent presentation of a fully formed substitute the very next day.Footnote 72 This would have been impossibly swift work for a lone MP still new to the processes of legislation. Wilberforce later told Hey that the second version of the bill had been written by the government's law officers and that “one of the most active judges” had consulted “with the rest of the bench at a general meeting” concerning its substance prior to its presentation to the Commons.Footnote 73

Having passed the Commons on July 29, 1786, however, the bill encountered fatal opposition in the Lords from Lord Chief Justice Loughborough. Although primarily offended by the government's omission to consult the judges beforehand (a charge that, as has been mentioned, Wilberforce explicitly denied), Loughborough also objected to the bill's aim of extending the most extreme sentence of English law then available beyond the crime of murder.Footnote 74 Such an alteration, he maintained, would be an “inducement to commit still greater crimes, … for surely nothing could be more obvious than that, if the same punishment were to attend the convict for burglary as for murder, breaking open a house would generally be attended with murder, as robberies in France were, the criminals there knowing that the commission of the one crime was to receive no greater punishment than the other.” Loughborough's views provide a concrete basis for some historians' perceptions of the bill as a regressive measure. However, the home secretary himself specifically refuted any notion that the bill was intended solely to enhance penal severity. Sydney denied “that the object of the Bill was founded in pure cruelty. This was an imputation so unmerited by the Gentleman who introduced the Bill [i.e., Wilberforce], that he could not suffer it to pass unnoticed. A more worthy, liberal and humane man did not exist; and all who knew him, he was sure, would join with him in declaring, that if any individual was more averse to anything like cruelty than others, that Gentleman was the individual.”Footnote 75

Wilberforce himself later maintained that Loughborough had known very well what the real purposes of the bill were and that he had opposed it solely for partisan political reasons.Footnote 76 That said, the alacrity with which government abandoned the bill suggests that Loughborough may not have been entirely wrong to perceive the temper of the times as being against any extension, beyond the crime of murder, of the most aggravated mode of execution.

An Age of Maximum Severity

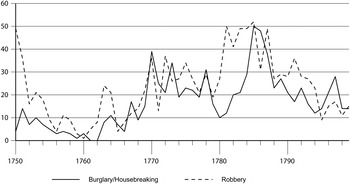

At the same time, however, other voices were contending loudly for maximum severity, and here we come to a second “humanitarian” intention behind the Felons Anatomy Bill. Even if its aims had been “pure cruelty” so far as those categories of felons to whom it applied were concerned, the bill had nonetheless enjoyed an unproblematic passage through the House of Commons. Rational, sympathetic, and humanitarian critiques of capital punishment had been making some headway during the 1760s and 1770s. The extraordinary scale of violent crime during the 1780s, however, prompted others to demand a reversal of this trend. Just a year before Wilberforce's bill, execution without exception for all capitally convicted criminals had been vigorously advocated by Martin Madan in his widely-read Thoughts on Executive Justice (1785). “Methinks,” Madan famously remarked, “that our laws are reduced to the state of [toothless] vipers – their sting is gone, their fangs are out, their terror is lost; … the laws shall hurt nobody, who chuses to sport with them.”Footnote 77 Many disagreed with Madan, but at least one member of the judicial bench seems to have endorsed his reasoning in the starkest possible manner. For the first time in decades—probably more than a century—every capital convict of the summer assizes for the counties of Essex, Kent and Sussex in 1785 was hanged without exception.Footnote 78 A few months later (and only two months before the Felons Anatomy Bill was introduced), the City of London had petitioned government to demand “that the sentence passed on convicts at the Old Bailey, may be fully executed, as a means of deterring those persons now at large, who are continually making depredations on the peaceful inhabitant, from persevering in their mal-practices.”Footnote 79 City officials could hardly have been taking exception to the execution levels of the previous year. Perhaps they were pushing back against the earliest signs of that relative restraint in the use of the gallows which characterized the year 1786, before the resumption of greater severity the year after (see Figure 1).

Pitt's ministry was thus confronted with a stark dilemma. On the one hand, when introducing the Police Bill in June 1785, it had publicly admitted that large-scale executions were wholly ineffective, and even counterproductive, as a deterrent. On the other, it was obliged to acknowledge strong views, both in the public at large and among the judges themselves, that less restraint, rather than more, was called for in deploying the threat of the gallows.Footnote 80 In attacking the Police Bill, two Aldermen of the City who also sat as MPs had insisted that the unremitting use of capital punishment was the best strategy for reducing crime in London. Benjamin Hammet lamented the prevailing spirit of compassion, which he thought currently prevailed with regard to “thieves and robbers,” maintaining that “it was to no purpose to multiply penal laws if they were not put in force.” Similar echoes of Martin Madan could be heard in the voice of James Townsend, who insisted that it was “the judge who reprieved enormous offenders, who committed cruelty, and not he who, by dooming such convicts to the fate of the justice of the country and its laws had called down upon them, held out an example of terror to others to avoid meriting a similar punishment.”Footnote 81 The Felons Anatomy Bill might, therefore, be understood as an effort by Pitt's government to steer a middle path between, on the one hand, a desire to execute fewer criminals, and a determination, on the other hand, to punish those who were to be executed with a more exemplary severity.

The Singular Problem of Burglary

This leads immediately to the third aspect of the bill, which suggests its ultimately humane intentions: its selectivity as to the categories of offenders to whom it would apply, namely convicted robbers, burglars, arsonists, rapists, and traitors. In practice, however, it would only be applied without exception to robbers whose crimes were “accompanied with wounding, beating or other circumstances of amorality”—in other words, exactly the same sorts of robbers who, in theory, were already routinely refused pardon as a consequence of the government's resolution of September 1782. In the case of the other four classes of offenders, however, each body would only be turned over for anatomization “upon application” from a surgeon.Footnote 82 Three of these four crimes—high treason, rape, and arson—generated far fewer convictions than robbery and burglary. Since 1750, the Old Bailey had produced only fourteen convictions for rape (only six of which actually ended in executions) and only one for arson. Similarly, only one person had been convicted of high treason in the strictest sense of that crime (an overt political betrayal of king and country), although if coining had been intended to be included in that category (as it would be in the strictest interpretation of the law), another fifty-two could be added to the score.Footnote 83 Rape, arson, and treason would have added, at most, on average, only one or two felons' corpses per year for the surgeons from 1750 to 1785 inclusive. In its most frequent operation, the bill was going to apply to selected categories of robbery and burglary, the former specified by the legislation and the latter (apparently) left to the vicissitudes of requests from anatomists.

In practical terms, then, the bill's most striking innovation would have been the public dissection of a substantial proportion of convicted burglars. Loughborough seems clearly to have grasped this particular aim of the bill, referring to how it proposed to apply “the same punishment … for burglary as for murder.” Even more significantly, that focus was emphasized in the home secretary's reply, in which (after having “rescued Mr Wilberforce's character”) he argued that, if Loughborough truly insisted that the judges must guide all adjustments to criminal law, he ought then to assist government in framing a new bill “to discriminate the various and distinct crimes classed under the general head of burglary, and to apportion distinct punishments [to them]. … He wished … to have the distinction legally laid down, that the house-breaker, in the worst sense of the word, might not be encouraged in his excess of criminality, from hearing that the offender of the lesser species of guilt, though his crime was classed under the same name as his own, was pardoned.”Footnote 84

No such bill specifying distinctive categories of burglary ever came forward, but Sydney's professed desire for it suggests the greatest concern that Wilberforce's bill was intended to address: the particular problem of unprecedentedly high levels of conviction for burglary in London and a need to make distinctions among them. When conjoined with Sydney's insistence on Wilberforce's humanitarian motives in sponsoring the measure, as well as the evidence that Pitt's government had taken an active hand in both backing and reshaping it, the real purpose of the Felons Anatomy Bill becomes clear. It was intended to provide a hard-pressed government with a credible strategy for executing fewer burglars without seeming to be “soft” on crime at a time when conviction levels for these worst sorts of capital felonies had reached truly horrific heights.Footnote 85

Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate how remarkably prominent burglary had become by comparison with robbery, the crime that was usually the benchmark of public and official concern about serious criminality in eighteenth century England.Footnote 86 In 1750, a year that saw extraordinarily high levels of conviction for robbery in the crime wave that followed the War of the Austrian Succession (1739–48), only one tenth as many people were convicted of burglary as of robbery.Footnote 87 From the late 1760s through 1778, however, the conviction rate for burglary suddenly surged from less than half that for robbery to being identical to it. This, as well as the increased numbers of executions that followed (see Figure 1), helps to explain why those two decades witnessed the first widespread expressions of doubt regarding the efficacy of hanging, as well as transportation, as deterrent punishments. Such reservations were apparent in such major publications at the time as the fourth and final volume of William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England (1769) and William Eden's widely read Principles of Penal Law (1771). They were also a central feature of the Parliamentary Committee of 1770, which was formed to address “the several Burglaries and Robberies that of late have been committed in and about the Cities of London and Westminster,” and that gave rise to the first, largely unsuccessful attempts to substantially reduce England's capital code.Footnote 88

Figure 2. Old Bailey convictions: burglary versus robbery, 1750–99. Source: Execution and Pardon: Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey, 1730–1837. http://hcmc.uvic.ca/.

Figure 3. Old Bailey: burglary as a proportion of robbery convictions, 1750–99. Source: Execution and Pardon: Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey, 1730–1837. http://hcmc.uvic.ca/.

What made burglary an especially urgent problem, as far as the execution levels of the mid-1780s are concerned, is demonstrated in Figure 4. Convicted burglars were usually more likely–and in the 1770s and 1780s, far more likely—to be hanged than were convicted robbers. In September 1782, when the government announced a policy of refusing pardons in London to anyone convicted of “robberies … attended with acts of great cruelty,” that resolution was made at the midpoint of a period (1779–84) in which robbery convictions were soaring by comparison with those for burglary (Figure 2). In practice, however, the immediately subsequent execution rates for robbery (1783–4) were among the lowest known before the last decade of the eighteenth century, whereas those for burglary were invariably high (Figure 4). Between 1780 and 1785, by comparison, and especially after 1783, convictions for burglary soared.Footnote 89 In 1786—the year of the Felons Anatomy bill—they enormously exceeded convictions for robbery for the first time in the memory of living contemporaries (Figures 2 and 3). This confluence of robbery and burglary convictions—which appears to have been unanticipated by government in September 1782—conjoined with a swift and substantial resurgence in the execution rate for robbery after 1784 on top of a persistently high execution rate for burglary, were the main factors in producing the unprecedented number of hangings in London between 1785 and 1787 (see Figure 1). As late as February 1787, the City of London was still seeking to impress upon government its continuing and particular concern about “the increase of burglaries” in the metropolis.Footnote 90

Figure 4. Old Bailey execution rates: burglary and robbery, 1750–99. Source: Execution and Pardon: Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey, 1730–1837. http://hcmc.uvic.ca/.

In the face of such alarming heights of criminal convictions, the government was unwilling to reduce the level of executions, as many voices in the press demanded they should, until it could find an effective means to reduce conviction levels for the worst categories of persistent criminality: robbery (a perennial problem), and burglary (one of newly formidable dimensions). Therefore, it is suggestive, when notice was first given to the Commons in early April 1785 that the government was preparing a police bill for the metropolis, that the man who gave that notice—William Selwyn, a lawyer (and cousin of Lord Sydney) who seems often to have drafted the home secretary's criminal legislation—declared the measure to be self-evidently necessary in light of “the alarming increase of burglaries and street-robberies” in London.Footnote 91 At this point, its proposed title was “a Bill for the more effectually apprehending and bringing to punishment, such persons as shall [be] found [to] be concerned in Burglaries and Highway Robberies.”Footnote 92 As has been mentioned, the scope of the bill that was finally presented two months later was far more extensive than merely “apprehending and punishing” robbers and burglars. Nevertheless, the ultimate objective was the same: to significantly reduce the number of people who were now paying the ultimate price for such crimes.

Finally, Wilberforce and Pitt were not alone in favoring postmortem dissection as a punishment for hanged felons other than murderers. Edward Thompson, the man with overall command of Britain's naval interests on the African coast, and with whom the government was consulting as to the prospects of establishing a convict settlement there, had proposed the idea to Lord Sydney in April 1785, and for many of the same reasons that underpinned the 1786 bill:

The Many Executions of Late, and the increase of Crimes and Criminals, have so greatly alarmed Society in general, that any mode which might be introduced to lessen the one and spare the other will be highly acceptable to the state and the nation. By a long attention to the last confessions of our Malefactors, I have often discovered a greater solicitude about the body than the soul: and that they have always confessed more dread at the dissection of their dead bodies than any particular distress about the death on the Gallows, which Leads me to recommend … ordering every body for Dissection that was executed. …

Besides, my Lord, it might be a means of leaving our dead Friends at peace in their Graves. For at present, for the want of subjects for the Surgeons, There are not less than two bodies a day furnished by the Resurrection men for dissection, at two Guineas each . . . .Footnote 93

Michael Angelo Taylor, the MP for Poole (Dorset), also agreed with much of this. In 1785, Taylor was identified in the London press as the leading parliamentary proponent of the Police Bill. The following year, he also took a leading role, alongside Wilberforce and Duncombe, in moving the Felons Anatomy Bill.Footnote 94 Taylor therefore provides another direct connection between the failure of 1785 and the proposal of 1786. For Taylor, a strategy for enhancing the deterrent impact of executions may even have had a paternal connection. Less than three years earlier, his father, the eminent architect and Sheriff of London, Sir Robert Taylor, had been the original mover of the proposal to abolish executions at Tyburn in favor of a more stylized and controlled execution ritual conducted immediately outside Newgate prison. That measure, subsequently adopted in other parts of the country during the ensuing years, can also plausibly be read as an effort to make execution more formidable and forbidding in its immediate appearances—more effective a deterrent—and thereby holding out the ultimately humane prospect of reducing both the number of capital convictions overall and the need for large-scale execution scenes. It did not work out that way, but it was meant to do so.Footnote 95

The Contingency of “Humanitarian” Measures

All of this serves as a reminder that the history of humane developments within any society and culture is by no means a straightforward, unidirectional phenomenon. It is not only, as Norbert Elias noted of “the civilizing process,” that there are phases of substantive reversion as well as progress in any given narrative.Footnote 96 We must also appreciate that the relative “humanity” of certain measures is often contingent upon the specific contexts of a given historical moment. In 1786 many officials genuinely believed—however preposterous that belief may look to later observers—that penal measures whose immediate impacts might seem unacceptably dreadful, arguably even by the standards of their own age (as Loughborough maintained), would nevertheless serve humane purposes when viewed in the larger perspective. Such beliefs may even have been entertained by men such as William Wilberforce, whose later credentials as a standard bearer of humanizing values otherwise seem more indisputable. The Felons Anatomy Bill would have imposed a more fearsome mode of capital punishment for people convicted of the most serious categories of crime next to murder, but it appears to have been intended to apply that punishment—and perhaps execution at all—to a smaller number of people than were being executed in the years immediately preceding its introduction. Moreover, by specifically reserving the option of rejecting applications by the surgeons for most types of felons, it also left open the means of ultimately reducing the scale of such aggravated executions once circumstances permitted. And finally, it is important to note that the bill's most immediate object—the provision of a significantly larger number of corpses for anatomical study than were currently available by legal means—meant to serve another humane purpose: to enable surgeons to make their incisions into the bodies of conscious individuals as accurate, and therefore as swift, as possible. The needs of medical science provided a necessary spur to the Felons Anatomy Bill; the execution crisis of the 1780s, and the intense arguments that it provoked, were its sufficient cause.Footnote 97

If this vision of a Wilberforce who was ready to make fine-grained distinctions in the pursuit of humanitarian aims still seems puzzling, it might finally be noted that he appears to have been decisively compelled by the “emergency” of the moment. Only ten years later, when another bill for “Anatomizing the Bodies of Felons executed for Burglary or Highway Robbery” was proposed, neither he nor Taylor appears to have spoken on its behalf, and it was immediately rejected by the House of Commons.Footnote 98 Both men presumably felt that the cruelties inherent in such a measure now loomed decisively larger than any of its potentially humane effects.Footnote 99 Such a feeling would have been reinforced by the fact that, by the mid-1790s, both capital convictions and executions in London had fallen to their lowest levels in thirty years (see Figure 1), drastically reducing any impetus for such a bill so far as the needs of criminal justice were concerned. The other intensely felt pressures of 1786 had similarly abated a decade later. The first anatomy bill had been proposed in the wake of the collapse of the two principal strategies that government had deemed essential to an effective system of criminal justice: the full-scale resumption of convict transportation and the reform of London policing. By 1796, both matters had been substantially resolved, the former by the settling of Botany Bay in 1788 and the latter by passage of the Middlesex Justices Act in 1792.Footnote 100 As crime was no longer so pressing a problem as it had been ten years earlier, and adequate means both to prevent and to punish it had (for the time being at least) been achieved, the space had now opened for a more decided expression of humanitarian distaste for a measure that now had no compelling rationale other than the desires of the medical establishment for more anatomical subjects. The immediate rejection of the proposed Anatomy Bill of 1796, in contrast with the near success of that of 1786, confirms that this latter factor could never, in itself, have been sufficient to ensure success.

The Proclamation Society and Government

There was perhaps one more compelling reason why Pitt's government had been so willing to take Wilberforce's anatomy proposal in hand in June 1786. It was at this exact moment that a revised version of the 1785 Police Bill, which Pitt had promised to introduce, was being quietly shelved. The principal reason for doing so appears to have been, as with the penitentiary project beforehand, the sheer scale of the costs that would be involved.Footnote 101 The government may also have now appreciated that any preventative measure that addressed the problem of crime in London alone was insufficient. Crime and its effective punishment had become an equally urgent problem—and an unprecedentedly persistent one, years beyond the end of the most recent war—outside the capital, and certainly in the counties of southeastern England. An expensive and politically contentious overhaul of the London magistracy might perhaps have reduced metropolitan levels of capital criminality and execution over the long run. A sharp enhancement of the horrors of execution among a select group of capital convicts could have done so sooner, and throughout the nation at large. Attention to the now national scale of the problem of crime also helps to explain Pitt's support for Wilberforce's second strategy for reducing the scale of executions in England.

This second effort is considerably better known to historians; it is also much more easily reconciled with Wilberforce's spiritual awakening of November 1785. Having failed to convince parliament that a more selective but dramatic exercise of capital punishment might be an effective and appropriate means to this end, Wilberforce and the government returned to a revised strategy for preventative policing, this time conceived on a national rather than a merely metropolitan scale. The basic animating principle remained the same as that adopted by government for London in the autumn of 1782: to prevent the development of serious criminality in its nascent stages by the more determined prosecution and punishment of petty offenses. On June 1, 1787 the king issued “A Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the preventing and punishing of Vice, Profaneness and Immorality.” Lamenting “the rapid Progress of Impiety and Licentiousness, and that Deluge of Profaneness, Immorality, and every Kind of Vice, which, … hath broken in upon this Nation,” the Proclamation required all subjects to obey, and all magistrates to enforce, the laws against profanation of the sabbath, excessive drinking, blasphemy and cursing, public gaming, licentious gatherings, and lewd publications. All English people, both rulers and ruled, were to be regularly reminded of their duties four times yearly by the reading aloud of the Proclamation at assizes and quarter sessions.Footnote 102

By this means, Wilberforce and the government meant, among other things, to reduce the scale on which capital punishment was now being practiced. “The barbarous custom of hanging has been tried too long, and with the success that might be expected from it,” Wilberforce told reformer and fellow Yorkshireman Christopher Wyvill. “The most effectual way to prevent greater crimes is by punishing the smaller, and by endeavouring to repress the general spirit of licentiousness, which is the parent of every species of vice.”Footnote 103 This most immediate purpose of the Proclamation was also readily apparent to sympathizers. “It gives me pleasure,” one wrote to Wilberforce soon after, “to find that you join in the ideas of many humane and thinking men, in reprobating the frequency of our Executions and the sanguinary Severity of our Laws. They have long shocked the Feelings of Humanity, and are totally inefficacious as to the obtaining the Object all penal severity ought to aim at, namely the Deterring others from committing Like Offenses.”Footnote 104 In other words, as Richard Follett has noted, “the connection Wilberforce made between moral reform and the reduction of crime [was] central” to this new endeavor.Footnote 105

As noted earlier, this basic strategy was not new. After William and Mary issued a proclamation “for the encouragement of piety and virtue, and the preventing and punishing of vice, profaneness, and immorality” in January 1691–92, similar ones were issued at the accession of each new monarch, from Queen Anne in 1702 to Victoria in 1837.Footnote 106 Their apparently close symbolic linkage with royal authority may date from the “Proclamation against vicious, debauch'd, and prophane persons” issued by Charles II soon after his return from exile in May 1660, which demanded that all the king's subjects should “cordially renounce all that Licenciousness, Prophaneness, and Impiety, with which they have been corrupted and endeavored to corrupt others, and that they will, hereafter, become examples of Sobriety and Virtue …”. The newly restored king promised that his government would “not exercise just Severity against any other Malefactors, sooner, than against Men of dissolute, debauch'd, and prophane Lives” and professed his hope that “the displeasure of good Men towards them, may supply what the Laws have not,” to which end he required all local officials “to be very vigilant and strict in the discovery and prosecution of all Dissolute and Prophane Persons, and such as Blaspheme the Name of God, by prophane Swearing and Cursing, or revile or disturbe Ministers, and despise the Publick Worship of God …”.Footnote 107 The issuing of this proclamation may have been an explicit bid, following the collapse of Cromwell's regime, to win the support of moderate Puritans for the restored royal order. The first comprehensive morals reform measure—“for the more vigorous and effectual putting in Execution the Laws against Sabbath-breaking, Swearing, Drunkenness, and Whoredom, with the greatest Severity”—had been issued by the Council of State in November 1649, perhaps with a view to enhancing its claims to godly legitimacy following the trauma of Charles I's execution earlier that year.Footnote 108

The Proclamation of 1787 was a significant departure from its eighteenth century forbears, however, in at least one notable respect. It was the first comprehensive proclamation for a reformation of manners to be issued outside the occasion of a monarchical accession. This timing reflected not only the emergency caused by the execution levels in London and elsewhere, but also several recent and uniquely powerful developments in English politics and society. One of these was a profound belief, among a middle class becoming more and more conscious of its economic and political power, that direction of the nation's affairs at the very highest levels, and not just the behavior of the people at large, was profoundly in need of correction.Footnote 109 That perception was animated by several prominent features of the national public discourse during the 1780s: the catastrophe of the war with America, the first major conflict in a century which Britain had indisputably “lost,” the enormously inflated national debt left in its wake, the political and constitutional crisis of 1782–84, levels of serious criminal conviction that had remained high far longer than might plausibly be explained solely by postwar social-economic dislocation, and a rapidly maturing consciousness, among many sectors of the nonelite propertied classes, that traditional aristocratic rule was inherently corrupt and essentially corrosive of the national public temper.Footnote 110 “The Scriptures teach us to consider national judgments, as punishments for national sins,” the evangelical educationist Sarah Trimmer wrote in September 1783. “[O]ur nation at present, is notorious for so many vices, that we may expect calamities at every turn.”Footnote 111

Following his conversion experience of November 1785, Wilberforce would have shared Trimmer's sense of God's providences at work in the nation at large. The crusade against the slave trade, in which he took so prominent a part, has been plausibly presented as a project to reclaim moral authority from Britain's erstwhile colonists in America.Footnote 112 The many personnel whom the antislavery movement shared with the Proclamation Society suggest that the latter must also have been conceived as part of a larger project for the re-moralization of English society. For Wilberforce, as for many others, commitment to a reformation of manners was also driven by a deep conviction that all men and women must ultimately answer for their personal omissions and failings at the seat of judgment. As he remarked to one young woman in November 1787, “the Christian's motto should be, ‘Watch always, for you know not in what hour the Son of Man will come.’” Similarly, in cautioning his own sister against the pleasures of theater going, he apologized for any offense his advice might give, but emphasized “that I see the vanity of all pursuits of this life, and with somewhat of a humble hope, through the mercies of my Redeemer, look forward to a better. … [W]hen I reflect that I shall have to account for my answer to [you] at the bar of the great Judge of quick and dead, I cannot, I dare not, withhold or smooth over my opinion.”Footnote 113 So might many of his fellow evangelicals and Proclamation Society members have replied if challenged to explain the formal severities of their moral position.

The basic idea for some such initiative as the Proclamation was in circulation almost immediately after the failure of the Metropolitan Police Bill in June 1785. One of its first prominent advocates was Thomas Bayley, Chairman of the Lancashire Quarter Sessions and the presiding force in that county's reconstruction of its county prison and houses of correction.Footnote 114 In addressing the grand jury at the quarter sessions on July 21, 1785, Bayley read out “the royal proclamation against vice, profaneness and immorality” (presumably that which had been issued at the king's accession a quarter-century earlier) and noted that “it contains excellent and important instruction for us all.” In announcing the county bench's unanimous resolve “to provide a New House of Correction and Penitentiary House” along the lines prescribed by the 1779 Penitentiary Act, Bayley also returned to a theme that the solicitor general had emphasized in presenting the Police Bill to parliament: “Our horror is almost continually excited by the dreadful accounts of multitudes of poor creatures who are hanged almost in childhood for the blackest crimes. At the fatal tree they all tell us—that they have never been taught to know God and their duty; have never been corrected for their early wickedness,—but been abandoned by their parents, and suffered at once to plunge headlong into vice and destruction.—How do these wretches punish us, by their villanies, for their neglected education?” Bayley saw a revitalized Sunday school movement as both essential to the nation's spiritual renewal (in the manner of Sarah Trimmer) and a central component of a more comprehensively effective approach to preventive policing.Footnote 115

Similar advocacy of renewed efforts to rigorously school the morals of the English people soon became a regular theme of newspaper correspondence.Footnote 116 Sometime in mid-1786, An Account of the Reformation of Manners, originally published in 1699, was reissued, “with some Remarks adapted to the present Period, and an Abstract of various Penal Laws,” by a society established in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, one with which Wilberforce may have been associated.Footnote 117 In April 1787, the grand jury at the Old Bailey presented a formal memorial to the City of London, lamenting the widespread conduct of business on Sundays, which they perceived to be a “great encouragement of vice and immorality, and consequently tending to the encrease and multiplying the melancholy business” of the criminal courts. Two months later, following issuance of the royal Proclamation, the City ordered copies of it to be “stuck up in the most conspicuous parts” of the town.Footnote 118

Whenever precisely he took up the cause, Wilberforce's close access to Pitt's government gave the movement extra influence, at least for a time. Home secretary Sydney circulated the Proclamation, first to all the chief magistrates of counties, then soon afterwards to all the high sheriffs, ordering them “to take the most early opportunity of convening the magistrates within” their counties “and enjoining them, in the strongest terms, to pursue the most effectual methods for putting the laws in execution” against “the profanation of the Lord's day, drunkenness, swearing, and cursing, and other disorderly practices.” Unlike the Proclamation itself, which emphasized immorality and vice in general, Sydney's circular took particular notice of the fundamentally related problem of crime: “of the depredations which have been committed in every part of the kingdom, and which have of late been carried to such an extent as to be even a disgrace to a civilized nation, …”.Footnote 119

Previous governments had similarly tended to support reformation of manners movements when such concerns appeared to dovetail with their own. The most strikingly active and sustained predecessors of the Proclamation Society, the Societies for the Reformation of Manners of the early eighteenth century, had enjoyed royal support during the Augustan era: partly because those years, too, were characterized by a crisis of large-scale criminal convictions (especially in London); but also because both monarchs of the time had compelling political and personal interests at stake. William III was concerned to give his seizure of the throne the appearance of divine sanction; Queen Anne may have been inspired more simply by a genuine desire to publicly manifest her own personal piety.Footnote 120 The 1730s saw a resurgence of government interest, partly from the concerns of public commentators—pious and otherwise—for the particular problems of alcohol-driven immorality during the years of the “gin craze,” but also from a pragmatic desire on the part of Sir Robert Walpole to use liquor licensing to boost government revenue, especially in the wake of his failed Excise bill of 1734.Footnote 121 The early 1750s gave rise to yet a third concentration of moral reform agitation, both within parliament and among society at large, driven not only (and again) by high crime levels, but also by a general sense of God's judgments upon English society, reflected not least in the reaction to the unprecedented occurrence of two earthquakes in London in 1750.Footnote 122

The Pitt government's support for the 1787 Proclamation can therefore be construed as simply a restatement of the October 1782 circular to London magistrates, additionally driven now by three years of the largest execution numbers in London in nearly two centuries, and intensive public arguments over both the morality and the efficacy of such displays. As we have already seen, all those executions were making little or no dent in the scale of criminal convictions at the Old Bailey. The government's support must also have now reflected a growing appreciation, during the intervening five years, that the problem of large-scale criminal convictions—straining beyond capacity the institutional resources even of some county authorities, such as those of Gloucestershire, Lancashire, and Oxfordshire, who were actively taking up the construction of large-scale prisons on the penitentiary model—was no longer confined to the metropolis.Footnote 123

There is little evidence that the support of government endured for very long after the Proclamation was issued in July 1787. The longer-term fortunes of the Proclamation Society and its mission have been detailed by other scholars, particularly Joanna Innes and Michael Roberts.Footnote 124 As far as government interest in particular was concerned, subsequent developments soon reduced the Society's relevance as far as resolving the penal crisis of the 1780s was concerned. By the early 1790s, on the one hand (and as we have already noted with respect to the failed attempt to reintroduce the Felons Anatomy Bill in 1796), large-scale convict transportation had been resumed, and a substantial reformation of metropolitan policing achieved. On the other hand, and sooner even than this, government had at last found an occasion on which to implement a dramatic and lasting reduction in the proportion of executions in London.

That occasion was King George III's first serious bout with porphyria, a congenital condition that manifested itself in symptoms of insanity, during the winter of 1788–89. The fate of each capital convict at the Old Bailey could not be determined until each of their cases had been reviewed by the king and the senior members of the cabinet at a meeting known as the Recorder's Report.Footnote 125 Ever since George III had ascended the throne in 1760, the regular practice had been to hold one such meeting for each of the eight annual sessions at the Old Bailey. The king's incapacitation between early November 1788 and the end of February 1789, however, meant that the Recorder's Report that was at last convened on March 13, 1789 was obliged to review no less than forty-eight capital cases from four accumulated sessions. If the more usual execution rates that had prevailed at Recorder's Reports during the previous five years (anywhere from one- to two-thirds) were to be applied on this occasion, somewhere between sixteen and thirty-two people would have been hanged after this one. The cabinet came close to doing just this: it left fourteen people to die the following Wednesday morning, a number that would have ranked with the largest gallows displays seen in London during the last decade.