Scholarly work has shown that gender concerns during war have been ill-addressed by national and international elites during transition or after conflict (Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim Reference Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim2010; Bueno-Hansen Reference Bueno-Hansen2015; El-Bushra Reference El-Bushra2007; Porter Reference Porter2007; Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg2013). In part because of that work, various international organizations have moved to place gender considerations at the forefront of their mission. Famously, this includes Resolution 1325, the United Nations (UN) Security Council’s landmark resolution on women, peace, and security, passed in October 2000. Over twenty years after Resolution 1325, we see more considerations of gender concerns, gendered violence, and the particular and varied ways that gender can make some populations more vulnerable than others in contexts of conflict and other forms of insecurity, which form the beginning of a shift in global norms, at least in policy language.

This study analyzes the change in roles and the roles available to women in pre-negotiation and framework-setting negotiation processes between the Colombian government and nonstate armed actors. The primary case in this study is the negotiation process between the Santos administration and the FARC in 2012–2016. Are gender concerns taken seriously, or are they used symbolically to trumpet liberal notions of inclusion during pre-negotiation and negotiation stages? I begin by examining the broader picture of the international climate of gender diversity and the shift in global norms regarding gender in these processes centered on UN Resolution 1325, and then take a closer look at the individual contexts of the above-named negotiations. This article offers evidence that inclusion of women in pre-negotiation and framework-developing processes in specific negotiation contexts has less to do with the international community’s calls for gender diversity and more to do with the character of the specific parties at the negotiating table and the ways in which they have waged war.

The recent peace accords between the leftist guerrilla group FARC and the Colombian government, signed in 2016, has been called a model for gender inclusion and offers a case in which we are likely able to observe gendered processes of interest (Hansen and Lorentzen Reference Hansen and Lorentzen2016). The international community has praised its inclusive model regarding both gender and ethnic issues via its subcommittees on gender and ethnic affairs. This study examines the motivations for the creation of subcommittees, as well as the ways in which women’s representation did or did not create impetus for this inclusiveness. The Colombian negotiations are also an ideal context to examine how women mobilized to have their voices heard, and the obstacles they faced. Rather than accept claims of gender inclusion at face value, this article elaborates on the story of gender inclusion, mobilization, and the roles available to women in the context of the most recent Colombian peace negotiations.

I situate these questions at the juncture of critical feminist literature on peace negotiations and informal networks literature. The data most central to my argument is a collection of twenty-five semi-structured one-on-one interviews with men and women who were present at the negotiation tables (mesas/redondas de negociación), some of whom were members of the official negotiation teams while others worked in background or supplementary roles during these processes. This article examines the roles available to women in the framework-setting, pre-negotiation, and negotiation contexts of the peace negotiations between the Santos administration and the FARC. It also discusses how the impetus for more inclusion of women’s issues was driven by mobilization of women’s and feminist organizations on the ground in Colombia, rather than by top-down initiatives for inclusion in negotiation processes.

Theory and literature

In the case of Colombia, as in many other complex interstate conflicts, there is a history of gendered violence perpetrated by military, paramilitary, and guerrilla forces. In addition to this history, we must problematize how gender affects equitable political participation and human security both during and after conflict.Footnote 1 The lack of security for the 1.6 million Colombian citizens who have been displaced due to violence in the recent years of the conflict has perpetuated problems of gendered violence. While gendered issues impact all members of a population, they create particularly vulnerable situations for women and their families, with Afro-descendant women and Indigenous women being among some of the most affected because of intersectional identities (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw2017).

Evaluating Resolution 1325

Using Anderlini’s (Reference Anderlini2004) definitions of peace negotiation processes, this article deals with “pre-negotiation” processes, in which people advocate to create space for dialogue, and framework-creation processes, such as both the Oslo and the Havana negotiation processes. Anderlini (Reference Anderlini2004) notes that Colombia has a history of including civilians at the table (e.g., civil society organizations). O’Rourke (Reference O’Rourke2014) addresses the ways in which Resolution 1325 and the larger agenda of women, peace, and security (WPS) prioritizes the participation of women in peace and security processes but do so by assuming preset interests that women have on these themes, as opposed to advocating for women actually being present in a variety of roles and making decisions about WPS priorities (O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke2014). O’Rourke (Reference O’Rourke2014) cites her concern about the possibility of the WPS agenda re-entrenching stereotypes about women, men, and peace. Bell (Reference Bell2013) takes an evaluative approach to the peace frameworks established after Resolution 1325. She advocates for an understanding that these processes are gendered from the outset, reinforcing the way war is waged. She finds that there are more references to women in peace frameworks after Resolution 1325, and that explicit references to women are more likely when the UN is a third party at the table (Bell Reference Bell2013). Furthermore, Anderlini (Reference Anderlini2007) discusses the ways in which the integration of framings of Resolution 1325 can be confusing and left open to interpretation regarding the key pillars of protection, participation, prevention, and peacekeeping, resulting in limited efficacy. Each of these concepts can be understood and implemented in peace process framings in many different ways. For example, prevention originally meant prevention of war but turned into prevention of gender-based and sexual violence (Anderlini Reference Anderlini2007, 15). In their seminal article, Bell and O’Rourke (Reference Bell and O’Rourke2010) use a large-N quantitative evaluation of all peace negotiation processes begun after the establishment of Resolution 1325 (all processes from 1999 to 2010). They find that theoretically, Resolution 1325 has increased references to women in peace frameworks from 11 percent to 27 percent when the UN is a third party at the table (Bell and O’Rourke Reference Bell and O’Rourke2010). They find that while Resolution 1325 has increased references to “women’s interests” in peace frameworks, these references do not systemically seek to evaluate or improve women’s substantive participation in those same processes.

In their work on peace negotiations, Bell and O’Rourke (Reference Bell and O’Rourke2010) observe that women’s interests are often seen as competing with the larger objectives of the process, which means that even if there are women physically present at the table, they may not bring up women’s interests due to fear of being viewed as extremist or radical. Ellerby (Reference Ellerby2013) echoes the concern of Bell and O’Rourke that women’s presence at a negotiating table does not equate with women’s substantive participation in those same processes. Ellerby also argues that women continue to find substantive ways to engage in peacebuilding outside of traditional peace negotiation processes. This is particularly true in the case of Colombia, where we see many women’s and feminist organizations organizing around themes of peacebuilding and environmental activism as well as social and economic justice reform.

The lack of acknowledgement of these complex realities after conflict makes it more difficult for women’s peacebuilding organizations to be taken seriously in postconflict negotiation and reconstruction processes (El-Bushra Reference El-Bushra2007). As implementation of those negotiated accords moves forward in Colombia, there continues to be a lack of consideration for the dual status as both victim and violator of many women who were involved with the conflict, along with assumptions that having women’s representation at the table equals the substantive participation of women and that “women’s interests” are monolithic and unitary.

Other feminist works have addressed the struggle to obtain additional and necessary considerations for women in postconflict settings. Corey Barr (Reference Barr2011) contends that linking gender-sensitive transitional justice and security sector reform is an essential step in peacebuilding. Barr (Reference Barr2011, 8) links peacebuilding, transitional justice, and security sector reform in her work, stating that “making these connections in a gender-sensitive manner can facilitative more effective, sustainable, and equitable peacebuilding efforts.” Despite increased international attention to the issue of gender, she states that these changes have not been implemented in a meaningful way. Sahin and Kula (Reference Sahin and Lucia Kula2018) claim that essentialist approaches to security during and after conflict shape international actors’ policies and projects. As a result, interventions during peacebuilding continue to be top-down rather than engaging with the lived experiences of women. Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim (Reference Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim2010) compare and analyze official language of the government of Sierra Leone as well as that of the UN and its entities during peacekeeping missions and postconflict reconstruction. They find that all institutions engage in what they term “empowerment lite” (Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim Reference Abdullah and Fofana-Ibrahim2010, 265). While various institutions engaged with feminist language for purposes of legitimacy, they failed to “put their money where their mouth is” when it came to allocating staff and resources for empowering and transformative projects. Feminist and gendered approaches problematize mainstream conceptualizations of gender roles in conflict and postconflict settings. This problematization has implications for the implementation of peace processes and further points to necessary structural transformations within institutions, as well as in society, to move toward a sustainable peace.

Women’s roles in peace negotiations

Studies prove that women’s participation in peace negotiations and peace processes creates more durable and lasting peace, and peace deals signed by women have higher rates of implementation (Krause, Krause, and Bränfors Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018). However, women continue to be primarily excluded from these processes. Between 1992 and 2011, only 2 percent of chief mediators and 9 percent of negotiators in peace processes were women (O’Reilly, Súilleabháin, and Paffenholz Reference O’Reilly, Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015). I find that with a few exceptions, similarly to the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations in Oslo, most women in the Colombian context were mid-level negotiators (with some issues siloed by the structure of the negotiations), advisors, spokespeople, and secretaries. Like Aharoni (Reference Aharoni2011), I posit that these roles were established due to a structured and gendered division of labor that at times served to diminish women’s visibility in this process. It was only through the mobilization of women’s and feminist groups that there was a push for representation of gender diversity at the Havana negotiations. As in the case of Burundi, implementation of the Havana Accords has demonstrated that while this process appeared to open political space for ethnic minorities and women, it failed to follow through with genuine political participation (Daley Reference Daley2007). Women were only appointed to “main table” negotiating positions after civil society mobilized for their inclusion, and they were treated as an “essentialist category” when they finally were (Daley Reference Daley2007, 343, 349). Along similar theoretical lines, Westendorf argues that women’s total exclusion or minimal inclusion in official peace processes can be seen as the “canary in the coal mine” in that in indicates elite ownership of peace processes, which has serious consequences of the sustainability of their implementation (Westendorf Reference Westendorf2018, 450).

All of this is to say that most of the time, official peace negotiations and processes reflect both how war is waged by the parties at the table and how the ownership of this process serves to reinforce existing power structures and dynamics. Women’s lack of inclusion and the ways they need to fight to be included at all in these processes show this, as the case of Colombia illustrates. At its peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s, FARC forces included approximately 30 percent female fighters.Footnote 2 Former female FARC combatants faced incidents of sexual violence and assault from fellow combatants in the field, and were subject to FARC’s policy of forced contraception and/or abortions for the female fighters in their ranks (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Carranza Franco Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Franco2017). At the same time, these women were also legitimate combatants in war and in some cases were responsible for kidnappings, extortion, drug trafficking, and extrajudicial killings of civilians. The lack of acknowledgement of these complex realities after conflict makes it more difficult for women’s peacebuilding organizations to be taken seriously in postconflict negotiation and reconstruction processes (El-Bushra Reference El-Bushra2007).

Inclusion and informal networks

Because of the nature of peace negotiations, they are often preceded by secret, informal processes before the official negotiating tables and framework negotiations are announced and begun. These informal processes can last years before the official negotiations begin and usually serve to set the agenda of the official process, with conversations about nonnegotiable items for all parties involved. They often take place in “hot house” environments, that is, a country or place far removed from the conflict and therefore from public access and engagement (Bell Reference Bell2013). These processes often lead to the creation of informal networks that endure (or remain active) throughout formal peace processes between chief negotiators, and these informal networks between negotiators are ones from which women are excluded from the start. While the nature of informal networks can make them difficult to study, there are examples of literature on informal networks which intersect business, politics, and political economy.

Krackhardt and Hanson (Reference Krackhardt and Hanson1993) characterize the formal structure of a company as the skeleton, and the informal network as “the central nervous system, driving the collective thought processes, actions, and reactions of its business units.” They emphasize the importance of social ties to informal networks and how difficult it is for managers to discern what those informal networks really look like among their employees. This holds true for informal peace negotiations. Often, third-party actors and government or international negotiators have previously existing social ties, either through past negotiations or some personal tie, which build trust in what is a very tense situation. Helmke and Levitsky (Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004) describe the “informal rules of the game” and advocate for a research agenda that critically examines informal institutions and why they emerge; in fact, the majority of political rules are constructed outside officially sanctioned channels (Knight Reference Knight1992; North 1990; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1994; Lauth Reference Lauth2000). From a public perspective, it is very difficult to understand or discern these informal ties, which may or may not lead to a successful unofficial primary peace negotiation. Dudley (Reference Dudley2004) describes the processes of formal and informal negotiations between the FARC and the Colombian government during Belisario Betancur’s presidency in the early 1980s, describing the relationship that some government negotiators had with the guerillas, thanks to their political pasts (Dudley Reference Dudley2004). If these informal networks and social ties are so important in agenda setting and subsequent success of more formal peace negotiations, it is vital to examine who is present during informal processes insofar as this information can be ascertained.

Theoretical contributions of the 2012–2016 Colombian negotiations

What roles were available to women in the framework-setting, pre-negotiation, and negotiation contexts of the peace negotiations between the Santos administration and the FARC? Implementation of the Havana Accords has demonstrated that while the negotiations appeared to open political space for ethnic minorities and women, it failed to follow through with genuine political participation (Daley Reference Daley2007, 343). Almost six years after the signing of the Havana Accords, we are seeing the consequences of this lack of sustainable implementation in Colombia. Since Colombia’s 2016 peace accords have been trumpeted as the most inclusive ever, this context offers us theoretical leverage to examine elite claims to inclusion in peace negotiation processes, as well as the empirical reality of those same processes.

Lived experiences of gendered violence during Colombia’s armed conflict

Gendered dimensions of conflict in Colombia’s armed conflict are intersectional, overlapping, and complex. Oftentimes, women are victimized multiple times over—fathers, sons, or husbands are disappeared or forcible recruited; women themselves are subject to opportunistic violence such as rape and forced abortion; and many are forcibly displaced because of these and other forms of violence. Nor are women safe when they are forcibly displaced; they often continue to face intrafamilial violence, intimate partner violence, and the same types of violence as they faced before they were forcibly displaced (Wirtz et al. Reference Wirtz, Kiemanh Pham, Saskia Loochkartt, Decssy Cuspoca, Rubenstein and Vu2014).

These gendered experiences of violence are compounded by intersectional identities. Violence and deterritorializing strategies used by armed groups (including the armed forces) in Colombia disproportionally affect Afro-Colombian and Indigenous women (Tovar-Restrepo and Irazábal Reference Tovar-Restrepo and Irazábal2014; Hernández Reyes Reference Reyes and Esther2019). Rural women and women who identify as LGBTQ+ have also been at risk. Rural women were and are frequent victims of violence as their homes and farms are the places where most of the fighting as a result of the armed conflict has taken place in recent decades; and LGBTQ+ women faced, and continue to face, “corrective” sexual violence against them by armed groups, particularly paramilitary groups (Gillooly Reference Gillooly2021; Hagen Reference Hagen2017).

Despite these continued experiences of violence, women in Colombia have consistently been a force for organizing and mobilizing for peace and against the multiple, overlapping, intersectional, and complex ways many of them experience violence. Rural women have mobilized against the colonial and militarized system of violence that permeates “all ambits of life”; Afro-Colombian and Indigenous women continue to mobilize against extractivism and the presence of armed forces; and still others construct collective organizing and resistance spaces, in spite of the additional threats they face as a consequence of their mobilization (Rodriguez Castro Reference Castro2021; Hernández Reyes Reference Reyes and Esther2019; Zulver Reference Zulver2017). So, what are women’s issues in this context? They are as varied, overlapping, and complex as the lived experiences of violence that women have faced as a result of the conflict.

Interview methodology

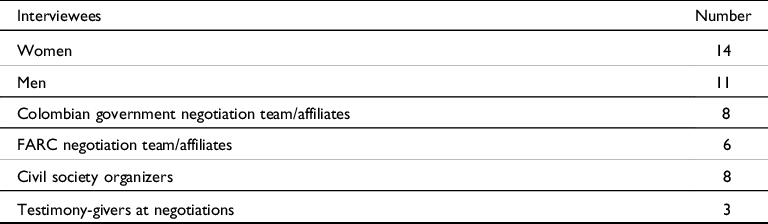

In the following empirical section, I draw from twenty-five semi-structured interviews from men (11) and women (14) who were involved in the negotiation process between the Colombian government and the FARC. These interviews were conducted between 2019 and 2020 and lasted between forty-five minutes to two hours. I interviewed main table negotiators from both the government (8) and FARC (6) teams; negotiators (8) who were at the Gender and Ethnic Subcommittee tables; people who worked in capacities like researchers and secretaries; and women (3) who gave testimony during the negotiation process itself (see Table 1). I gathered these interviews via snowball sampling: at the end of each interview, I asked my interviewee if they would be able to provide me with the names of two others who had worked on the negotiations in some capacity. In my interviews with feminist and women’s organizations, I found the names of some of the primary organizations who organized during the cumbre (summit), and snowball sampled from there. I previously had some affiliations or contacts with feminist organizations in Colombia, so I asked my established contacts to put me in touch with some of the primary organizations and organizers who were a part of the cumbre.

Table 1. Interview demographics.

Where are women at the negotiating table? Evidence from Colombia

The liberal notion of “add women and stir” has been widely criticized for its lack of nuance and its superficial commitment to inclusion and diversity. I start with this concept to demonstrate the changes that have been made in peace negotiation team composition over time, but I argue that these changes are superficial and that traditional gender roles still constrain the ability of women to participate in a central, substantive, and truly intersectional fashion. A key issue here is who is involved in the informal pre-negotiation processes, as described earlier. I interrogate the role of civil society in advocating for women’s substantive participation in the negotiation processes, the demand of the FARC for a more gender-equitable process, and the Colombian state’s response to that demand. This section presents a complex spectrum of perspectives regarding the concepts of equitable participation and inclusion surrounding the theme of gender in the peace negotiations, drawing from ethnographic examples and interview data from those involved in the 2012–2016 negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC. Why, how, and in what roles are women included in formal peace negotiations?

The 2012–2016 negotiations with the FARC: Back of the room, side of the table

The 2016 accords between the FARC and the Colombian government ended decades of start-and-stop negotiations between the two groups and reached a conclusion with the final ratification of the accords by the Colombian National Assembly in November 2016. These accords have been praised by both international and national communities for their inclusiveness and special considerations, particularly surrounding gendered, Indigenous, and Afro-Colombian concerns. Footnote 3 A part of the praise levied at these accords is due to the inclusion of subcommittees specifically for the concerns of gender and ethnic groups at the final mesa in Havana (the Gender Subcommittee and the Ethnic Commission/Chapter), through which I found there to be the problem of “piggybacking” issues of race and gender at the main table (Bell and O’Rourke Reference Bell and O’Rourke2010). That is to say, instead of being centrally featured as issues, they were added on to what were perceived as more mainstream concerns. I problematize the praise of the accords as perhaps a bit presumptuous and point out the many ways in which these groups continued to be pushed to the margins during the formal process of negotiation, as well as the preceding informal processes. I gathered evidence to this end through the interviews described above, the secret exploratory talks in 2011, the agenda-setting and more formalized framework-setting discussions in 2012 in Oslo, and the subsequent peace negotiations from 2014 to 2016 in Havana.

Mobilizing for inclusion in the Havana Accords

The first official and publicly recognized negotiations between the Colombian government and FARC began in Oslo, Norway, in October 2012. These negotiations were a preliminary dialogue: essentially, a negotiation of what would be on the agenda, or the roadmap of negotiations for the official process later in Havana, Cuba. At this point in time, there were no women serving as official negotiators in Oslo for either the government or the FARC. This remained the case until approximately one year into the negotiations, at their official beginning in Havana. In October 2013, women from across Colombia convened for the National Summit on Women and Peace, where they petitioned the government to include the perspective and concerns of women, which up to that point had not been centered in the negotiations. This cumbre was created primarily through the alliances of the Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Campesinas, Negras e Indígenas de Colombia (ANMUCIC); Casa de la Mujer; Coalición 1325; Colectivo de Acción y Pensamiento – Mujeres, Paz y Seguridad; Conferencia Nacional de Organizaciones Afrocolombianas (CNOA); Iniciativa de Mujeres Colombianas por la Paz (IMP); Mujeres por la Paz; Red Nacional de Mujeres; and Ruta Pacífica de las Mujeres (ONU Mujeres Reference Mujeres2017). In spite of some of the central work that Indigenous and Afro Colombian organizations did in the work of organizing this civil society pressure, none were included at the primary negotiation table.

Following the organizing and pressure of women and feminist civil society organizations, then president Santos appointed two initial female negotiators to the government team, María Paulina Riveros and María Angela Holguín. A member of the government team stated: “I mean there were a ton of women there before then. Lots of them working in advisory roles, but the government only had men as negotiators. I’m not sure if that would have changed if the women working in civil society hadn’t been very organized and very strong about their desire to see that change.” Footnote 4

One of the legacies of conflict in Colombia is a strong and well-organized civil society. Organizing around women’s issues and rights are particularly strong. As in any type of movement or organization, however, tensions and divisions exist. One of these pronounced divisions is between groups that identify themselves as women’s organizations and those who identify as feminist organizations. A director of one of the organizations that was active in the 2013 National Women’s Summit and subsequent summits explained this division:

So we identify as a feminist organization, which is not the same as a women’s organization. A feminist organization is not just for women—it’s for all of society. It is anti-patriarchal, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist. Women’s organizations have completely different priorities. However, we all managed to join together for this common goal; we could all agree the total lack of women on the government negotiating team was not acceptable. When you put all of us together, we really got things done. But because of these differences, cooperation didn’t last long in that same way long after this particular cumbre. I mean, I think there is respect on all sides, but there is also a division. Footnote 5

A representative from a self-identified conservative women’s group said the following: “Yes, we worked with many different types of groups on the problem of women’s representation at the negotiations.” When I asked her about the differences between their ideological stances compared to other groups, she cited abortion as a key issue:

We do not support the right to abortion in this organization. This is a huge ideological difference between us and some of the feminist groups we mobilized with, in this particular instance. I didn’t really feel that our collective cooperation would extend far beyond this issue because of what a difference this is [right to abortion] between us and them, and the fact that in this conflict, abortion was a real issue. But, on the fact that there needed to be women represented and negotiating [in Havana], we could at least agree on that.Footnote 6

Liberal, or in some cases radical, feminist organizations and conservative women’s organizations understood that neither side had any intention of changing ideological stances that both viewed as irreconcilable. There were also disagreements between organizations concerning how to mobilize. Some organizations wanted to protest and take to the streets, while others preferred to more quietly lobby their international and government connections on a personal level to achieve results. However, of the ten different feminist and women’s organizations involved in the cumbre that I spoke with, all agreed that it was only through this combination of strategies that they achieved tangible results.Footnote 7

This example of deep ideological divisions within the feminist and women’s movements highlights one of the very issues with thin or superficial commitments to gendered concerns. Women’s issues or concerns, particularly in transitional or postconflict settings, are not homogeneous or monolithic, as this example demonstrates. Treating them as such is another way of precluding genuine and varied participation, an issue that the WPS agenda sometimes contributes to by assuming a set of preset interests that apply to all women.

The Gender Subcommittee

In 2014, a subcommittee on gender formed at the negotiations in Havana. This committee was supposed to report its findings to the main negotiating table and make recommendations to be included in the final overall agreement. Footnote 8 The three women newly appointed to the FARC and government negotiation teams (María Angela Holguín, María Paulina Riveros, and Victoria Sandino) used the global norm of Resolution 1325 to push for the establishment of the Gender Subcommittee. Riveros stated: “The work of [the] Subcommittee will start from the complexity of a gender approach, and will overcome traditional or cultural value-based models. Only women, with diverse experiences, all of them, from their particular and superimposed conditions, will be the origin and the end of our task” (Ruiz-Navarro Reference Ruiz-Navarro2019). Here, we see the issue of allowing a very small group of people decide how women’s or gendered interests are to be represented and decided. While the Gender Subcommittee has been applauded for its creative solution to inclusivity, I argue that in some ways, the subcommittees (on both gender and ethnic groups) contributed to a continuation of marginalization. Rather than Afro-Colombians, Indigenous persons, and women being centrally included at the main mesa, they were sidelined through subcommittees and still did not have seats at the main table. This is not to say that the subcommittees were not called for or did not achieve important gains for marginalized groups in their participation in the negotiations; rather, the siloing of marginalized groups through subcommittees allowed this system to sidestep true inclusion and avoid centering voices most impacted by the conflict, while signaling that inclusion was in fact achieved. Were it not for sustained and long-term mobilization by both ethnic minorities and women, it is likely that they would not have been included as negotiators at all (Gillooly Reference Gillooly2021).Footnote 9

Interviewees were divided on whether the subcommittee helped or hurt the integration of gendered concerns in the accords. In the summer and fall of 2018, I conducted several interviews with those who had participated in or observed the Havana talks. One woman from the Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz stated:

Sure, there were lots of women present at the main negotiating table in Havana. A ton. I would say that somewhere between 40 and 60 percent of people at the main table were women at any given time. However, they were all in roles such as secretaries, notetakers, assistants. Either that or, they were female victims who had been brought in to give testimony. But most of the main spots at the big table were for men. The only place that there were a majority of women was on the subcommission for gender. Mostly, women worked in the background.

A female negotiator who was on FARC’s team praised the gender inclusion efforts, stating: “I do think that women were centered and prioritized during the negotiations, and it was because of FARC’s commitment to gender equality and inclusion that made it happen.” Footnote 10 In this context, the FARC negotiator indicated that it was not the government’s commitment to gender equity that created these opportunities for women’s voices to be heard but rather the pressure of civil society and of the guerrilla group. Members of the FARC negotiation team, when asked if they and the government were equally committed to gender in the negotiations, all responded that FARC’s commitment to gender equality was much stronger than that of the government. When members of the government team were asked the same question, they rated the FARC’s and the government’s interest in gendered concerns as the same during the negotiation process. FARC team members cited the initial lack of women on the government’s negotiation team and the current presidential administration’s lack of commitment to reintegration for former combatants, particularly considerations for former female combatants, to account for their perception in differences of commitment to the theme of gender and peace.

Overall, opinions about how significant the role of women was in this process were varied. One could argue that this variance in response is in line with the idea that, again, women’s needs and issues are not monolithic, and neither are gender concerns.Footnote 11 Some interviewees (both men and women) agreed that the structure of the 2016 accords was more than sufficient for the inclusion of women in decision-making and framing processes, citing that “this is the most involvement that women have ever had in a peace process before.” Footnote 12 Others disagreed, stating that the creation of the subcommittee for gender had allowed gendered concerns to be siloed during the negotiation process and that the final product of the accords reflected that. Still others said that neither the government nor the FARC were particularly committed to gendered concerns, and that it was only through the pressure placed on both parties by civil society organizations that women were included at the highest levels of negotiation and that gendered concerns were taken seriously at the main table.

A note on gender representation at the 2016–2019 negotiations with the ELN

While conducting my interviews with government and FARC negotiators, I included some questions regarding negotiations with the leftist guerrilla group Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) as a way to examine if negotiators believed that inclusion of women at the table would continue to increase in future processes or not. Was the inclusion that came about due to the pressure of civil society to include more diverse negotiators something that would continue over time, or did they feel that it was unique? The peace negotiations with Colombia’s second-largest guerrilla group, the ELN, are currently stalled, with no plans in sight to restart. Footnote 13 However, prior to the disbandment of the negotiations, the ELN teams featured a more gender-diverse group of preliminary negotiators than ever before in Colombia. At its inception, the main negotiating table featured three women (out of twenty-four team members) on the part of the ELN. When asked about the government’s commitment to gender diversity at the negotiating table, and if that trend would continue in future negotiations with the ELN, a government negotiating team member stated: “I don’t think so. I think the only reason why the FARC negotiations looked the way they did was because of FARC … the number of women they had in their ranks. The ELN has fewer women and seems less committed to these ideas of gender.” Another government team member stated: “Twenty-four team members? It was incredibly difficult to negotiate with only six members with the FARC. I couldn’t imagine the way a negotiation would go with that many people at the primary table. It would be impossible to make progress.” The ELN has a vastly different organizational structure than the FARC, which might account for the number of initial negotiating team members. The ELN has a more horizontal chain of command rather than a vertical, militarily structured hierarchy like the FARC had. There is no way to know if this will continue in the future, or what the new round of negotiators will look like if the process between the ELN and the Colombian government ever starts again, but gender diversity seems to be an idea that the state can take or leave according to their interests, rather than one it is willing to integrate fully into these processes.

Informal networks and negotiations

It is important to note that in between and prior to the formal mesa between the FARC and the Colombian government, there have been several informal and preliminary negotiation processes that did not result in the formation of official negotiations. These processes are held in secret and often are not officially claimed by either party participating until they either succeed and move on to more formal processes, or fail and are made public (primarily to blame the other party for a transgressive action that resulted in the breakdown of the preliminary talks). Participants or negotiators in these processes are also almost always exclusively male. Even in agenda-setting negotiations in Oslo 2012, which could serve as an example of a process somewhere between official and informal, there were no women present as negotiators on either team. There were women present, but only in advisory or support positions. This gender disparity in secret negotiation processes has important implications for women being taken seriously in peace negotiations and subsequent peacebuilding and transitional justice mechanisms, and reveals the pervasiveness of the mindset that “men fight wars,” although feminist security scholarship has proven that this is not the case.

Conclusion

When women are not included on the ground floor of peace negotiations, they often end up excluded from the very processes that they actively mobilized to produce. This has further implications for implementation of peacebuilding and transitional justice processes in postconflict or transitional contexts. The best way to have a truly inclusive and equitable peacebuilding process is to have a variety of voices heard from the very beginning of the negotiating process. Gendered notions of who participates and how they do so in war, peacebuilding, peacemaking, and informal networks continue to harm prospects for inclusive peace. In spite of governments and international organizations, such as the United Nations, placing gender equity at the center of their language, on-the-ground practice is often very different and slow to change. This article has raised these issues of inclusion not to denigrate the gains in participation that have been made thus far, but rather to avoid uncritical and overblown praise of these processes as they move forward.

The accords between the Colombian government and the FARC are one of the most ambitious peace processes to date. Almost six years after their ratification, there have been significant obstacles to implementation, which has been slow and piecemeal (Gillooly and Zvobgo Reference Gillooly and Zvobgo2019). Interviews with negotiators at the main table and subcommittees, support staff, civil society members, and people brought in to provide testimony reveal a spectrum of opinions regarding the inclusion of gendered concerns during the negotiation process. Some viewed the subcommittee for gender as a hindrance rather than a help to the inclusion of gendered concerns; others saw a true and significant commitment to gender diversity and gendered concerns on the parts of both the Colombian government and the FARC; and others believed there was a total lack of concern for gender issues, and only through pressure from feminist and women’s civil society organizations were there wins for inclusion in this process.

Much as in literature on critical human security, there is a wide variety of opinions on how best to approach the problem of gender in peace processes and subsequent implementation. While the 2016 peace accords between the Colombian government and the FARC included a diversity of gendered concerns unlike ever before, there continues to be significant space for improvement in those considerations. Improvements would include more women at the main negotiation table in the first place. This is not to imply that just because someone identifies as a woman, they are gender experts or will negotiate with a focus on gendered issues. This problematization is line with the idea that women’s concerns are not homogeneous. However, there need to be a diversity of perspectives at the table. There were no Afro-descendent or Indigenous women at the main negotiating table. This is an absence that is important to note, considering that these populations were particularly targeted in many different ways throughout the course of the conflict. Another issue with the considerations for gender put forth in the 2016 accords is follow-through. While the gendered foci in the accords are innovative, they are being implemented more slowly than the other points of the accords (Heinzekehr Reference Heinzekehr2018). Being a female social leader or human rights defender advocating for implementation of the accords is particularly dangerous: killings of female activists increased by 50 percent between 2018 and 2019, the majority of those targets being Afro-descendent, Indigenous, or campesino women (Associated Press 2020). The lack of consideration for gendered concerns at the beginning of these peace processes has concerning sequences down the line when it comes to building a sustainable peace.