Article contents

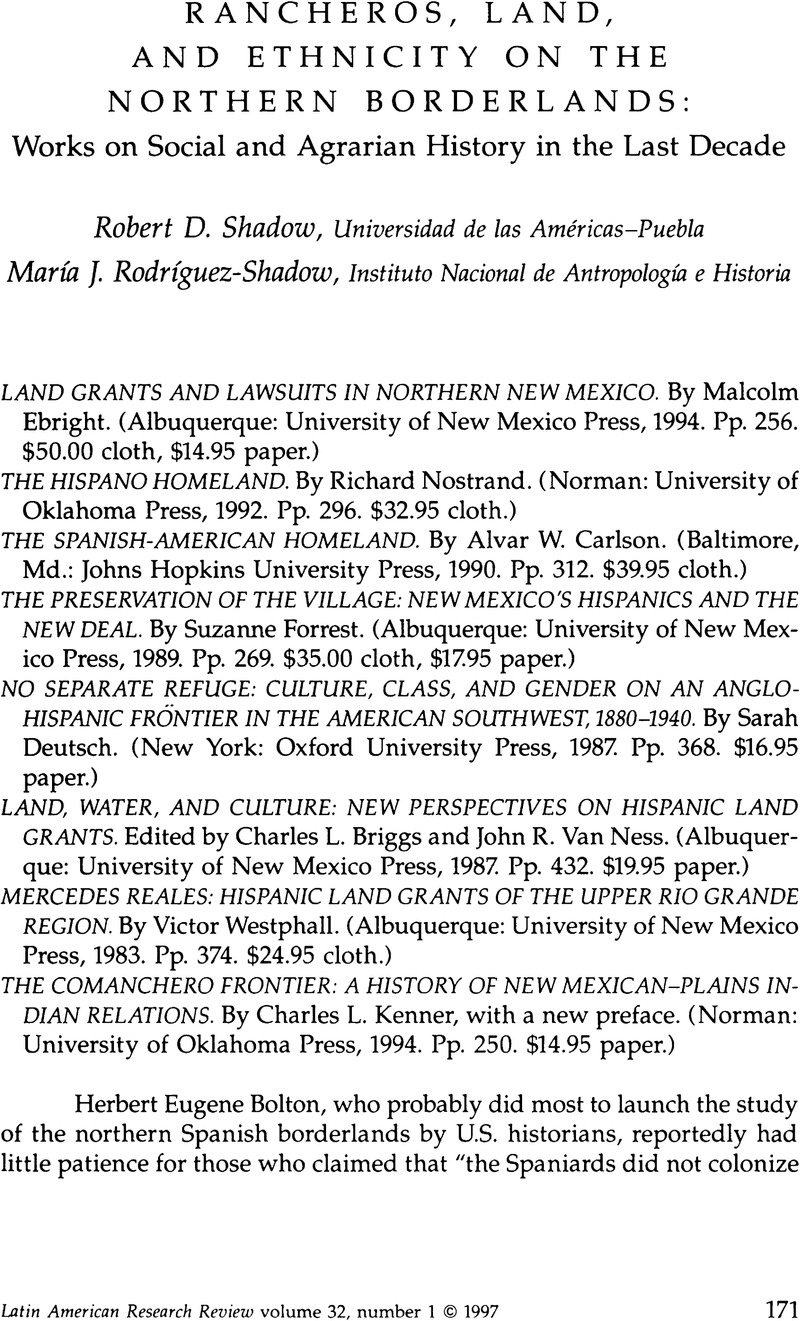

Rancheros, Land, and Ethnicity on the Northern Borderlands: Works on Social and Agrarian History in the Last Decade

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1997 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Cited in David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992), 7.

2. John Francis Bannon, The Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1531–1821 (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970); Arthur L. Campa, Hispanic Culture in the Southwest, 2d ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993); Charles E. Chapman, The Founding of Spanish California: The Northwestward Expansion of New Spain, 1687–1783 (New York: Macmillan, 1916); Nancie L. González, The Spanish-Americans of New Mexico: A Distinctive Heritage (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1967); Oakah Jones, Los Paisanos: Spanish Settlers on the Northern Frontier of New Spain (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979); Jones, Nueva Vizcaya, Heartland of the Spanish Frontier (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988); Carey McWilliams, Al norte de México: El conflicto entre “Anglos” e “Hispanos” (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1968; originally published in 1948); Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1966); Michael M. Swann, Tierra Adentro: Settlement and Society in Colonial Durango (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1982); and Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America.

3. Gerald D. Nash, “New Mexico since 1940: An Overview,” in Contemporary New Mexico, 1940–1990, edited by Richard W. Etulain (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994). In the opening section of his historical overview of New Mexico, Nash states, “But the Spaniards were not primarily a colonizing people, and found New Mexico disappointing because it did not yield large hoards of precious metals, unlike Mexico and Peru” (p. 2). New Mexico unarguably disappointed those who hoped to find treasures and a docile labor force. Pre-industrial Spanish settlers, like their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, chose first the most attractive locales to settle in terms of mineral and agricultural resources as well as the possibilities for trade. On these counts, New Mexico certainly was not a prime location. Nash lost sight of the fact that until the coming of the industrial revolution and the railroad in the late nineteenth century, relatively few Anglo settlers found much in New Mexico to convince them to settle there either.

4. National Geographic is obviously a premier source for the creation and perpetuation of popular imagery. Its July 1995 Map Supplement of the Rocky Mountains propagates the dichotomy that depicts Spaniards as soldiers and missionaries and Anglos as settlers. In a brief overview of the natural and cultural history of the Rocky Mountains, the article comments, “In the 1500s Spanish soldiers moved north from Mexico, looking for legendary cities or gold. Clerics followed, established missions and converting Pueblo Indians in what is now New Mexico. Most U.S. settlers pushing west in the 1840s wanted only to safely breach the unavoidable mountain barrier on their journey to lush farmland in Oregon and California.” See the unbound map, “Heart of the Rockies,” Supplement to National Geographic (July 1995). This characterization of Spaniards as subjugators and Anglos as colonists and developers is also found in the imagery presented in a 1982 map that divided the post-sixteenth-century history of “the Southwest” into two main periods: “Spanish Conquest, 1540–1820” and “Anglo-American Entry and Occupancy, 1820–1900.” See the unbound map, “The Making of America: The Southwest,” Supplement to National Geographic (Nov. 1982).

5. Philip Wayne Powell, Soldiers, Indians, and Silver: North Americas First Frontier War (Tempe: Arizona State University, 1975); María del Carmen Velázquez, Colotlán: Doble frontera contra los bárbaros (Mexico City: Cuadernos del Instituto de Historia, UNAM, 1961); Andrés Fábregas, La formación histórica de una región: Los altos de Jalisco (Mexico City: CIESAS and Casa Chata, 1986); and Robert D. Shadow, “Conquista y gobierno español en la frontera norte de Nueva Galicia: El caso de Colotlán,” Relaciones: Estudios de Historia y Sociedaa 8, no. 32 (1987):40–75.

6. John O. Baxter, Las Carneradas: Sheep Trade in New Mexico, 1700–1860 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987).

7. See Barter, Exchange, and Value: An Anthropological Approach, edited by Caroline Humphrey and Stephen Hugh-Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

8. Like the word market, cambalache is a generic term referring to both places and modes of exchange. In general, it refers either to the nonmonetary exchange (barter) of goods or to reciprocity between labor and services.

9. See for example J. J. Bowden, “Private Land Claims in the Southwest,” a massive six-volume work presented as an M.A. thesis at Southern Methodist University, 1969; and “Land Title Study,” conducted by White, Koch, Kelly, and McCarty and the New Mexico State Planning Office in 1971.

10. John Van Ness, “Foreword,” Mercedes Reales, ix; and Briggs and Van Ness's introduction to Land, Water, and Culture: New Perspectives on Hispanic Land Grants. See also William de Buys, “Fractions of Justice: A Legal and Social History of the Las Trampas Grant, New Mexico,” New Mexico Historical Review 56, no. 1 (1981):71–97; and Malcolm Ebright, The Tierra Amarilla Grant: A History of Chicanery (Santa Fe, N.M.: Center for Land Grant Studies, 1980.) See also the various essays published in Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico and Colorado, edited by John R. and Christine M. Van Ness (Manhattan, Kans.: Sunflower, 1980).

11. See Eric Wolf, “Facing Power: Old Insights, New Questions,” American Anthropologist 92, no. 3 (1990):586–96; and Wolf, Europe and the People without History (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982).

12. See Gary B. Nash, Pieles rojas, blancos y negros (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1988), 81, 148, a Spanish translation of Red, White and Black: The Peoples of Early America (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974).

13. Friedrich Katz, “Introduction: Rural Revolts in Mexico,” in Riot, Rebellion, and Revolution: Rural Social Conflict in Mexico, edited by Katz (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988), 11–12.

14. For a recent debate on “objectivity” versus “militancy” in the social sciences, see Roy D'Andrade, “Moral Models in Anthropology,” Current Anthropology 36, no. 3 (1995):399–408; and Nancy Scheper-Hughes, “The Primacy of the Ethical: Propositions for a Militant Anthropology,” Current Anthropology 36, no. 3 (1995):409–20.

15. David G. Gutiérrez, “Significant to Whom? Mexican Americans and the History of the American West,” Western Historical Quarterly 24, no. 4 (1993):519–39.

16. Ibid., 525–27.

17. Mario Barrera, Race and Class in the Southwest: A Theory of Racial Inequality (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979).

18. Gutiérrez, “Significant to Whom?” 536.

19. Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past and the American West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987).

20. One of the most important studies in this genre is Thomas D. Hall, Social Change in the Southwest, 1350–1880 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989).

21. For more on the role of artists and the struggle over culture in New Mexico, see Sylvia Rodríguez, “Tourism and Race Relations in Taos: Toward a Sociology of the Art Colony,” Journal of Anthropological Research 45, no. 1 (1989):77–99.

22. The romantic vision of integrated life in rural communities projected onto New Mexico villagers at this time paralleled the current trends in cultural anthropology, especially evident in the descriptions presented by ethnographers like Robert Redfield of Tepoztlán and other Mexican communities. Years later, Oscar Lewis provided an entirely different and much less attractive interpretation of the same community, touching off one of the first postmodernist debates in anthropology over ethnographic authority, anthropological objectivity, and the question of representation. See Robert Redfield, Tepoztlán, a Mexican Village (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1930); and Oscar Lewis, Life in a Mexican Village: Tepoztlán Restudied (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963).

23. For an incisive critique of the ideology and practice of indigenismo in Mexico, see Alan Knight, “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo,” in The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870–1940, edited by Richard Graham (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990), 71–113.

24. Ibid., 87.

25. Although Forrest contends that this image was thoroughly buried during the 1930s, it was exhumed by the “hippies” of the 1960s and 1970s, who (like their romantic ancestors at the turn of the century) believed they had found nirvana among the “simple folk” of northern New Mexico. The “hippie” lifestyle and the pillaging of abandoned homes greatly offended most local residents, who roundly repudiated the “hippie invasion.” Study of the similarities and differences between the first wave of artists and “eccentrics” in the early twentieth century and the hippie invasion of the Vietnam era awaits its historian.

26. David H. Dinwoodie, “Indians, Hispanos, and Land Reform: A New Deal Struggle in New Mexico,” Western Historical Quarterly 17, no. 3 (1986):291–323.

27. The volume falls squarely within the historical geographic tradition perhaps best represented by D. W. Meinig, and it carries forward the work of Oakah Jones, who is committed to studying the history of Spanish-American cultural diversity within the northern borderlands. See D. W. Meinig, “The Mormon Culture Region: Strategies and Patterns in the Geography of the American West, 1847–1964,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 55, no. 2 (1965):191–220; and Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on Five Hundred Years of History, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986, 1993); and Oakah L. Jones, Jr., Los Paisanos: Spanish Settlers on the Northern Frontier of New Spain (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979).

28. Sylvia Rodríguez, The Hispano Homeland Debate, SCCR Working Paper no. 17 (Palo Alto, Calif.: Stanford Center for Chicano Research, 1986).

29. The principal forum for the debate was the Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Many threads are woven throughout this often acrimonious debate, and some of the most extreme accusations and epithets are understandable only in the context of the charged political atmosphere of the late 1960s and 1970s. See the following contributions to the Annals of the Association of American Geographers: Richard L. Nostrand, “The Hispanic-American Borderland: Delimitation of an American Culture Region,” vol. 60, no. 4 (1970): 638–61; Nostrand, “Mexican Americans circa 1850,” 65, no. 3 (1975):378–90; Nostrand, “The Hispano Homeland in 1900,” 70, no. 3 (1980):382–96; Niles Hansen, “Commentary: The Hispano Homeland in 1900”; and Nostrand, “Comment in Reply,” the last two articles both in 71, no. 2 (1981):280–83. Finally, see J. M. Blaut and Antonio Ríos-Bustamante, “Commentary on Nostrand's ‘Hispanos’ and Their ‘Homeland,‘”; Nostrand, “Hispano Cultural Distinctiveness: A Reply,” and the rejoinders by Marc Simmons, Fray Angélico Chavez, D. W. Meinig, and Thomas D. Hall, all in Annals of the Association of American Geographers 74, no. 1 (1984).

30. Rodríguez “Hispano Homeland Debate.”

31. Rodríguez, “Land, Water, and Ethnicity in Taos,” 320.

32. Despite the sociological reality of the homeland concept for Upper Rio Grande villagers, the term itself is definitely an Anglo academic imposition. In Spanish, local residents convey the ideas and images of this concept with the designations “la nacioncita de la Sangre de Cristo” and “la tierra sagrada, agua bendita,” ethnopolitical expressions that differentiate, sacralize, and thus legitimize Hispano occupation and possession of the land.

33. See Luis González González, “Terruño: Microhistoria y ciencias sociales,” in Región e historia en México (1700–1850), edited by Pedro Pérez Herrero (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de México, 1991.)

34. See Edward Spicer, The Yaquis: A Cultural History (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1982).

35. See Rodríguez, “Hispano Homeland Debate.” On the “icons” and “emblems” of boundary maintenance, see James W. Fernández, “Enclosures: Boundary Maintenance and Its Representations over Time in Asturian Mountain Villages (Spain),” in Culture through Time: Anthropological Approaches, edited by Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1990).

36. Anthropologists will recognize the similarities between the geographers' “homeland” and the concept of culture area that U.S. ethnographers and cultural geographers developed during the 1930s. Basically, the culture-area concept envisioned culture as a bundle of “things” such as kinship terms, forms of courtship and marriage, arrow-release patterns, types of shelters, puberty rights, moccasin design motifs, projectile points, penis sheaths, ad infinitum. According to this perspective, the study of culture entailed mapping these traits and trait complexes through time and space to unravel historic connections, patterns of diffusion, and cultural relations.

37. Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, Regiones de refugio (Mexico City: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano, 1967). See also John P. Hawkins, Inverse Images: The Meaning of Culture, Ethnicity, and Family in Postcolonial Guatemala (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984).

38. Claudio Lomnitz-Adler, Exits from the Labyrinth: Culture and Ideology in the Mexican National Space (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992).

39. Other researchers whose studies are questioned by Carlson include William de Buys, “Fractions of Justice”; Robert J. Rosenbaum, Mexicano Resistance in the Southwest: “The Sacred Right of Self-Preservation” (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981); and Victor Westphall, Mercedes Reales.

40. See Rodríguez, “The Hispano Homeland Debate” and “Land, Water, and Ethnicity in Taos.”

41. Cristina Szanton Blanc, Linda Basch, and Nina Glick Schiller, “Transnationalism, Nation-States, and Culture,” Current Anthropology 36, no. 4 (1995):683–86.

42. José Manuel Valenzuela Arce, “El color de las sombras: Chicanos, identidad, acción social y racismo,” 1994 manuscript, 225–26.

43. This question has been raised by John R. Van Ness in “Review of Alvar W. Carlson's The Spanish-American Homeland: Four Centuries in New Mexico's Rio Arriba,” manuscript, p. 2.

44. See Ralph H. Vigil, “Inequality and Ideology in Borderlands Historiography,” LARR 29, no. 1 (1994):155–71.

45. Personal conversations with Sylvia Rodríguez, Arnie Valdez, and Devón Peña, 1992 to 1995.

46. See Malcolm Ebright, Land Grants and Lawsuits; and Robert D. Shadow and María Rodríguez-Shadow, “From Repartición to Partition: A History of the Mora Land Grant, 1835–1916,” New Mexico Historical Review 70, no. 3 (1995):257–98.

47. Ebright, The Tierra Amarilla Grant; de Buys, “Fractions of Justice”; Westphall, Mercedes Reales; and David Benavides, “Lawyer-Induced Partitioning of New Mexican Land Grants: An Ethical Travesty,” 1990 manuscript.

48. For an overview of Euro-American ideas on native peoples' common lands and the relationship between their conquest and the expansion of private property, see Nash, Red, White, and Black.

49. For recent documentation of the extent and nature of racism and discrimination in everyday life in the U.S. Southwest, see Menchaca, “Chicano Indianism”; and especially Douglas E. Foley, with Clarice Mota, Donald E. Post, and Ignacio Lozano, From Peones to Políticos: Class and Ethnicity in a Texas Town, 1900–1987 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988).

50. Cited in Rodríguez, “The Hispano Homeland Debate,” 4.

51. William Roseberry and Jay O'Brien, “Introduction,” Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and History, edited by O'Brien and Roseberry (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991), 1.

- 2

- Cited by