Article contents

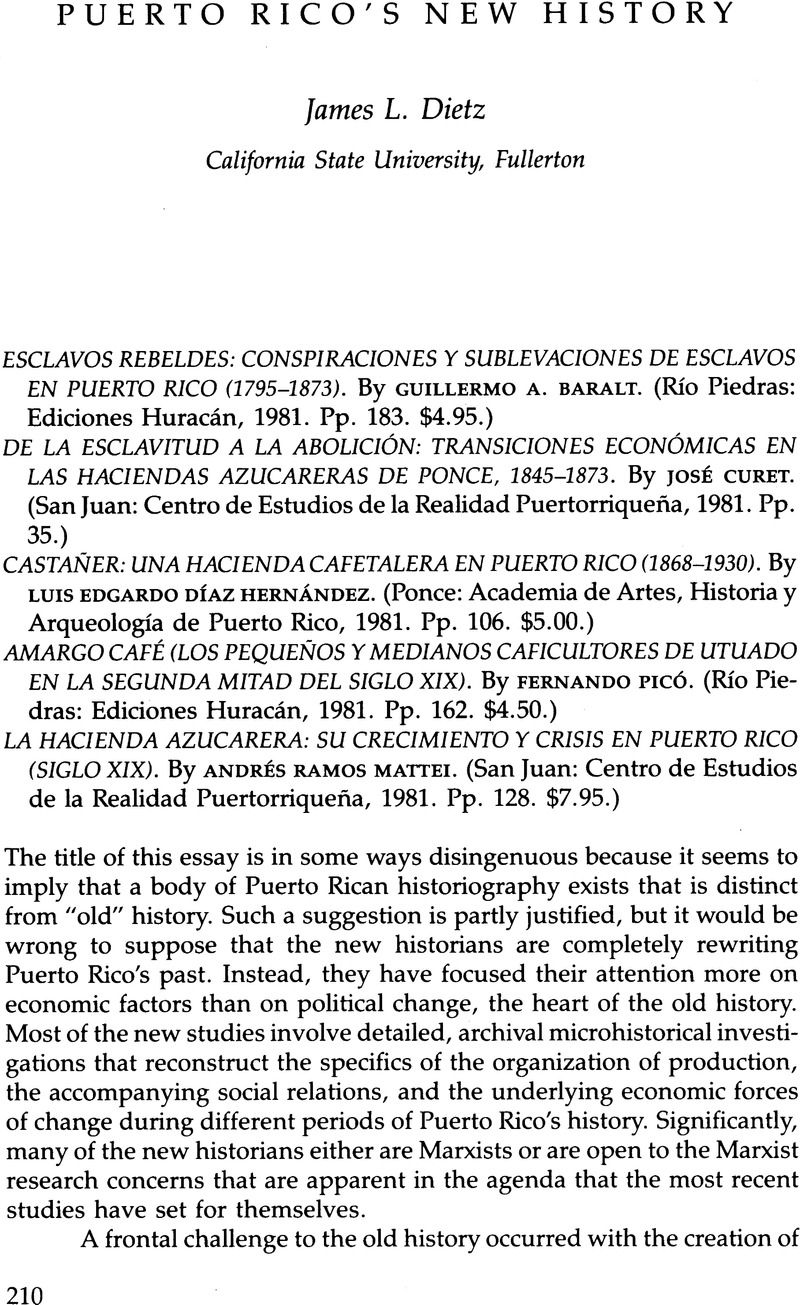

Puerto Rico's New History

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1984 by Latin American Research Review

References

Notes

1. Ediciones Huracán has published the bulk of the book-length new history in inexpensive paperback editions. Many CEREP publications, although frequently cited, have not been widely distributed until recently, when CEREP began its outreach program. The Anales de Investigación Histórica, which began publication in the 1970s, is also a valuable source. The even more recent Caribe, a student-edited journal from the Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe in Old San Juan, has published articles in the new history mold in its early issues and promises more such work in the future. The formation of the Asociación Histórica Puertorriqueña in 1982 may also contribute to furthering such work.

2. Published in English as Workers' Struggles: A Documentary History, edited by Angel Quintero Rivera (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976).

3. Amargo café is the third volume of Picó's study of nineteenth-century Utuado. The other two are Registro general de jornaleros, Utuado (1849–1850) (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1976); and Libertad y servidumbre en el Puerto Rico del siglo XIX: los jornaleros utuadeños en vísperas del auge del café (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1979).

4. See Laird W. Bergad, “Toward Puerto Rico's Grito de Lares: Coffee, Social Transformation, and Class Conflict, 1828–1868,” Hispanic American Historical Review 60, no. 4 (Nov. 1980): 617–42. On the role of immigrants, see the valuable collection edited by Francisco A. Scarano, Inmigración y clases en el Puerto Rico del siglo XIX (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1981).

5. Another useful study related to the organization of the coffee economy is Carlos Buitrago Ortiz, Los origines históricos de la sociedad precapitalista en Puerto Rico (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1976). This study examines another coffee hacienda, Hacienda Pietri, in southwest Puerto Rico.

6. One of the first acts of the Grito de Lares uprising also had been to burn the books listing debts. See note 4 above.

7. I became aware of it from a notice in Dr. Carmelo Rosario's column in El Mundo, “Temas históricos de Puerto Rico.” This column is a weekly treasure of information.

8. Picó, pp. 123–24, and Baralt, pp. 169–70.

9. Reproductions of Mercedita's tokens can be found in Maurice M. Gold and Lincoln W. Higgie, The Money of Puerto Rico (Racine, Wis.: Whitman, 1962), p. 38.

10. Luis Díaz Soler, Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico (Río Piedras: Edición Universitaria, 1965), pp. 117, 121, 122. In Ponce, slaves made up 61.1 percent of the total population in 1840, the highest concentration on the island (Baralt, Esclavos rebeldes, p. 131). In the work force, of course, the percentage of slaves was larger than their representation in the general population.

11. Angel Quintero Rivera, “Background to the Emergence of Imperialist Capitalism in Puerto Rico,” in Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans, edited by Adalberto López and James Petras (Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman, 1974), pp. 87–117. Also, Conflictos de clase y política en Puerto Rico (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1976). I mention only those of his works most immediately concerned with the nineteenth century. Quintero is perhaps the most prolific of the new historians.

12. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Taller de migración (New York: CUNY, 1975) and Labor Migration under Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979).

13. On women, see Edna Acosta-Belén, La mujer en la sociedad puertorriqueña (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1980), which includes the work of Marcia Rivera Quintero.

14. Sidney Mintz, Caribbean Transformations (Chicago: Aldine, 1974); “Labor and Sugar in Puerto Rico and Jamaica, 1800–1850,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 1, no. 3 (March 1959): 237–81. James Wessman, “The Demographic Structure of Slavery in Puerto Rico: Some Aspects of Agrarian Capitalism in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Latin American Studies 12, no. 2 (Nov. 1980): 271–89; “The Sugar Hacienda in the Agrarian Structure of Southwest Puerto Rico in 1902,” Revista/Review Inter-Americana 8, no. 1 (Spring 1978): 99–115; “Toward a Marxist Demography: A Comparison of Puerto Rican Landowners, Peasants and Rural Proletarians,” Dialectical Anthropology 2 (1977): 223–33.

- 1

- Cited by