Latin America’s largest federations have experienced a decade of economic growth, coupled with an egalitarian turn in politics, and a notable reduction in national income inequality (Reference Lustig, López-Calva and Ortiz-JuarezLustig, López-Calva, and Ortiz-Juarez 2013). These trends may signal a new era as Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico “break with history” to put redistribution at the forefront of their policy agendas (Reference De FerrantiDe Ferranti 2004). Brazil stands as a shining example of a country able to implement a large-scale, successful program of redistribution that has made a dent in the nation’s high poverty levels.

Explaining falling inequality in the 2000s, while important, should not detract focus from continuing severe, structural inequalities in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. While abject poverty is undoubtedly decreasing in the region, income gaps remain high. Arretche’s (Reference Arretche2015) recent edited volume documents this case well for Brazil. The authors show marked progress in reducing inequities between 1960 and 2010, but also stubbornly high overall inequality between rich and poor, whites and nonwhites, men and women, and across regions. Iniguez-Montiel (Reference Iniguez-Montiel2014) demonstrates that redistributive trends that had continuously reduced inequality and poverty from 1996 to 2006 in Mexico regressed beginning in 2006. Dalle (Reference Dalle2010) reveals that Argentina’s levels of inequality have not fully recovered from the spike in the 1990s, despite economic improvements in the 2000s and pro-poor policy reforms.

A substantial body of research suggests that Latin American federalism is an important barrier to transformative policies to redistribute income in the region (Reference GibsonGibson 2004; Reference Díaz-CayerosDíaz-Cayeros 2006; Reference BorgesBorges 2013). In this article we focus on a distinct set of institutional constraints on the scope of redistributive efforts in Latin America’s federations: the role of economic geography in shaping the relative weight of territories versus citizens in the organization of fiscal structures. The central puzzle we examine is why the fiscal structures essential to redistribution are so different in Latin American federations versus wealthier federations.

We examine the territorial structure of inequality (the distribution of income and productivity within the nation) as a constraint on centralized redistribution. We argue that the regional spread of income in federations and related malapportioned political institutions stymie national majority coalitions in favor of centralized efforts to equilibrate income. To support our claims, we first show a cross-national relationship between interregional inequality and malapportionment and redistributive effort in democratic nations. Our results suggest that Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico diverge greatly from Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) federations on the variables central to our theory.Footnote 1 Subsequently, we demonstrate empirically that distributive preferences in national legislative institutions are much more favorable toward interregional redistribution (transfers to states and provinces) than interpersonal redistribution (transfers to low income individuals) in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Consistent with these demands, Latin America’s large federations redistribute resources primarily to regions; however, the progressivity of intergovernmental transfers remains limited by legislative representation that shifts voting power away from potential recipients of centralized redistribution. We thus contribute to a recent wave of scholarly work examining institutional legacies that shape the degrees of freedom for egalitarian reform in Latin America (Reference WibbelsWibbels 2017; Reference Pérez-Liñán and MainwaringPérez-Liñán and Mainwaring 2013; Reference GargarellaGargarella 2010).

The question of redistribution in federations is a core issue in political economy. In democratic capitalist economies, fiscal systems are designed to provide both insurance and redistribution. These efforts appear more limited in federal nations (Reference BoixBoix 2003). Yet federations vary widely in the scope of their redistributive efforts. Differences in advanced industrial federations are generally recognized, but the variation among developing federations and between federations at different levels of development remains less explored (Reference GonzálezGonzález 2016). The large federations of Latin America offer an important testing ground for the theories linking federalism to distributive demands because they feature very high levels of inequality and growing economies that increasingly possess resources to affect the spread of income.

Fiscal structures in federal systems combine two dimensions, interpersonal redistribution, or policies to equalize the income distribution in the country as a whole, and interregional redistribution, or transfers of resources between different levels of government, such as the Länder Finanzausgleich in Germany, the Structural Funds in the European Union, and Coparticipación Federal in Argentina. A bird’s-eye view of federations around the world reveals important differences in the combination of these two dimensions. While Germany presents very high levels of both interpersonal and interregional redistribution, other federations such as the United States and Canada redistribute relatively little on either dimension. Except for the European Union, all advanced industrial federations have developed large-scale systems of interpersonal redistribution.

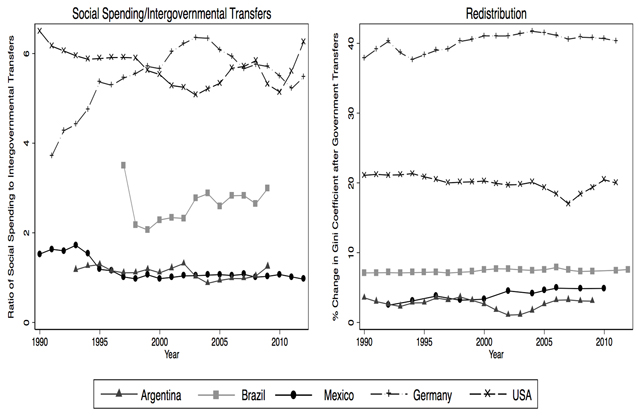

In sharp contrast, the fiscal structures of developing federations are dominated by interregional redistribution (Reference RoddenRodden 2006). In Figure 1, we compare the Latin American federations we study to two developed federations with very different approaches to redistribution, Germany and the United States. Figure 1 (left) documents systematic differences in interregional and interpersonal approaches to redistribution over time in these nations, measured as the ratio of social spending to intergovernmental transfers. Germany shows a consistently high commitment to interpersonal redistribution in addition to its generous interregional transfers. The United States redistributes at moderate levels on both dimensions, but social spending substantially outpaces interregional transfers. Latin American federations, in contrast, devote very little to social spending and spend amounts similar to or higher than those seen in wealthy democracies on intergovernmental transfers. Figure 1 (right) shows fiscal redistribution, measured as the percentage reduction in the national Gini coefficient due to government policies. All three Latin American federations have very low levels of interpersonal redistribution in comparison to the advanced industrial nations. Brazil’s redistribution is highest, around 7 percent, while Mexico and Argentina average 3 percent. As Figure 1 shows, Germany averages around a 40 percent reduction in the Gini coefficient, and even US policies more than triple the redistributive effect of the most generous Latin American federation. These levels are consistent over time, which suggests an equilibrium pattern of redistribution.Footnote 2 What accounts for the limited interpersonal redistributive scope of Latin America’s federal fiscal systems?

Figure 1: Interregional and interpersonal redistribution in selected federations. Redistribution is measured as the percentage difference in the Gini “market” value and Gini “net” after social transfers and taxes (Reference SoltSolt 2009). Sources listed in appendix Table A1.

Building on recent literature on endogenous fiscal structures, we argue that the territorial structure of inequality is crucial to understanding limited interpersonal redistribution (Reference Bolton and RolandBolton and Roland 1997; Reference BeramendiBeramendi 2007). There is clear evidence in advanced industrial federations of a link between the territorial structure of inequality and the decentralization of redistributive policy (Reference BeramendiBeramendi 2012). Federal representation and territorial distribution of central resources lead political actors to think in terms of regions as well as the nation as a whole. Fiscal structures within political unions are known to have discernible political and economic effects. Hence, regional actors factor their expectations of those effects, and the relative position of their region, into preferences over institutional structures. Fiscal systems are associated with distributive outcomes because distributional concerns play a fundamental role in their selection and design. Given a budget constraint, this implies the existence of a trade-off between interpersonal and interregional redistribution. What seems distinctive to Latin American federations is that powerful political actors have successfully shifted the redistributive efforts of the national government from the interpersonal to the interregional dimension (Reference PortoPorto 1990; Reference Artana, López-Murphy and PortoArtana and López-Murphy 1995). Our approach places the persistent levels of inequality in Latin America into alignment with a general argument about the nature of redistribution in large-scale federations.

Our focus on this subset of federations is both analytical and empirical. Analytically, we provide a general theoretical logic through which the distributive tensions associated with different structures of inequality shape fiscal systems in federations around the world. Empirically, we present new data on the territorial structure of inequality in Latin America that sheds light on past and future redistributive efforts. Inter and intraregional inequality have frequently been assumed to be important to politics in Latin American federations, but this proposition has received little empirical attention (Reference GonzálezGonzález 2012, Reference González2016; Reference WibbelsWibbels 2005). We further demonstrate that regional representation that favors less populated regions (malapportionment) appears to exacerbate the distributive pressure toward interregional transfers and away from centralized interpersonal redistribution (Reference Dragu and RoddenDragu and Rodden 2011). In addition, we relate our arguments to existing research linking Latin American federalism to patronage, fragmented party systems, and politicized interregional transfers (Reference GibsonGibson 2004; Reference Gibson and CalvoGibson and Calvo 2000; Reference GervasoniGervasoni 2010).

The Logic of Redistribution in Federal Nations

What distinguishes the organization of redistribution in federal versus nonfederal nations? In ideal terms, redistribution is unidimensional in fully centralized systems. That is, the centralized system of taxes and transfers redistributes income both between citizens and, implicitly, between territories, and there is no functional distinction between interpersonal (henceforth, t) and interregional redistribution (T). By contrast, all federations feature a budgetary differentiation between these two fiscal tools. Some policies aim to insure against individual-level risks or provide assistance, thus preventing an excessive gap in terms of disposable income (t). These interventions are distinct from those aimed at equalizing the level of fiscal resources across regional governments (T).Footnote 3 Accordingly, redistribution in federations is a two-dimensional political problem. The scope of redistribution in federations depends on (1) the distribution of preferences among citizens and regions, and (2) the rules governing the aggregation of preferences within the system of representation. To illustrate what sets Latin American federations apart from other unions with much larger redistribution, we use a theoretical framework combining both elements (Reference BeramendiBeramendi 2012).Footnote 4

Preferences

Figure 2 maps the distribution of preferences in an abstract federation for both interregional and interpersonal distribution. Each quadrant displays preferences over t and T for rich (denoted with subscript R) and poor (denoted with subscript P) citizens in regions that vary in their average income (x-axis) and in their level of inequality (ranging from more equal (superscript e) to more unequal (superscript u)). For instance, TRu = 0 and tRu* → 0 in the top-right corner suggests that affluent individuals in rich, unequal regions prefer low interregional transfers (T) and low interpersonal redistribution (t approaching 0), where both t and T are bounded between 0 (no redistribution) and 1 (full redistribution). We assume in this analysis that individuals’ preferences for redistribution are driven exclusively by income motives (Reference Moene and WallersteinMoene and Wallerstein 2001), thus excluding the role of labor market risks and insurance motives. Our goal is to capture the trade-off between interpersonal and interregional redistribution in its simplest terms.

Figure 2: Redistributive preferences in federations.

Distributive dynamics vary depending on regional income levels, individual income levels (subscript R and P), and regional distributions of income (superscript e and u). Take first the preferences of the rich. For upper-income people, regardless of their region’s income, their optimal choice is to minimize t. Given the union’s income distribution, the higher the levels of interpersonal redistribution, the greater the income extracted from them. High levels of inequality thus increase the resistance of the rich to t. The cross-region division among the rich comes from preferences for interregional redistribution. Rich individuals in rich regions prefer low levels of interregional redistribution, because the less resources drained from the region, the higher the level of public goods they can provide. The rich in the poor regions, however, have a strong preference for T that grows stronger the higher the level of inequality. In the first place, a large-scale system of interregional redistribution will liberate them of some of the burden imposed by redistribution in the region, by transferring resources away from the rich in the rich regions. This imposes a rent extraction by the rich among the poor on the rich among the rich. Second, they want to minimize the degree of interpersonal redistribution provided in their region so as to maximize the pool of resources from which they can effectively capture rents. For these purposes, interregional transfers provide rents to elites and resources to regional politicians that centralized interpersonal redistribution targeted directly at individuals could not fulfill (Reference FenwickFenwick 2009).

Lower-income people broadly agree to maximize interpersonal redistribution, and high levels of inequality intensify demands for t. The preferences of the poor across provinces at different levels of income diverge regarding interregional transfers. Lower-income people in poor regions want to maximize rents extracted from the rich regardless of where they reside. These are the citizens who would be better off under a fully centralized, highly redistributive system (Reference Bolton and RolandBolton and Roland 1997). Given that such an option is constitutionally excluded in federations, their optimal policy bundle would be one that maximizes interpersonal redistribution (t) as well as interregional transfers between territories (T). The latter ensures that local elites have enough resources to equalize income among individuals; the former would imply that such equalization actually takes place. The poor in the rich regions, in contrast, want to minimize the transfers from their tax base toward the poorer citizens in the poor region (low T). For this subset of citizens, large levels of interregional redistribution would imply a transfer of resources from themselves to the poor in the poor regions. These figures suggest that preferences among poor voters that strongly prefer redistribution are divided over the balance of t and T.

From Preferences to Outcomes: Inequality, Representation, and the Politics of Redistribution

The next step requires explaining the connection between the distribution of preferences and the fiscal structures detailed already. To that end this section focuses on the connection between the distribution of income across regions from which preferences emerge and the system of representation. Our analysis builds on three premises. First, we conceive of politicians as motivated by their desire to stay in office and to capture rents, with their preferences informed by the costs and benefits of interpersonal and interregional redistribution. Retaining office depends on a minimum stock of resources to fund the spending programs that enable the formation of necessary electoral coalitions. As a result, both interpersonal and interregional redistribution matter simultaneously for incumbents’ positions in the federal bargain because office seeking (and ultimately rent extraction) is conditional on the size of their tax base, which depends on the agreements reached with other partners in the union.

Second, the translation of institutional preferences into fiscal structures is not automatic but is mediated by the system of representation of political and economic interests. Accordingly, how different systems of representation condition the balance of power between contending groups is critical, as it ultimately shapes the process of preference aggregation and institutional choice (Reference Dixit and LondreganDixit and Londregan 1996; Reference Crémer and PalfreyCrémer and Palfrey 1999). The key institutional dimension affecting the aggregation of regional interests and the translation of preferences into outcomes is legislative apportionment (Reference Rodden and ArretcheRodden and Arretche 2004). A perfectly apportioned system implies that the value of any individual vote is the same regardless of a voter’s geographic location. In the extreme, the voice of individuals fully crowds out the voice of territorially organized interests. Alternatively, with very high levels of malapportionment the interests of territories dominate the formation of the national will as regional elites can veto legislative or institutional changes against their interests. Malapportionment is typically implemented through the selection of the upper legislative chamber, purposefully designed to ensure overrepresentation of less populated territories and, in some cases, such as Argentina and Brazil, the lower chamber as well.

Our final assumption is that there is a direct link between the level of malapportionment and strategies of political mobilization. In equilibrium, a strongly malapportioned legislature contributes to a more fragmented party system, which enhances the voice of territories at the expense of citizens (Reference Samuels and SnyderSamuels and Snyder 2001). Strong parties attenuate regions’ role in national politics by altering the cost-benefit calculations of regional leaders.Footnote 5 By contrast, in heavily malapportioned developing nations, local leaders are powerful relative to central organizations, and many engage in sustained clientelistic exchanges, particularly in the least populated, most overrepresented regions, as a way to perpetuate their own political survival.Footnote 6 We assume that there is a strong connection between the scope of malapportionment and the pervasiveness of nonprogrammatic forms of political exchange (Reference SoaresSoares 1973; Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and BruscoStokes et al. 2013; Reference Kitschelt and WilkinsonKitschelt and Wilkinson 2007).Footnote 7

Based on these three premises and using the preferences laid out in Figure 2, we analyze the process of preference aggregation and the formation of possible political coalitions. Assuming a minimum level of inequality—a feature common to all democratic federations—it follows that as inequality increases:

1) The resistance of the rich in rich regions to interpersonal redistribution increases (tRe* → 0 > tRu*).

2) The support for redistribution by poor citizens in both rich and poor regions increases. (tPu* → 1 > tPe*).

3) The support for interregional transfers among both the poor and the rich in the poor region increases (TPu > 0 > TPe and TRu > 0 > TRe).

The set of possible coalitions among the groups depicted in Figure 2 is potentially diverse. What governs the formation of coalitions that shape observable fiscal structures? To address this question, consider a contrast between two hypothetical unions. In the first, the level of inequality is relatively low and the system of representation is reasonably apportioned. In the second, there are very high levels of inequality (both interregional and interpersonal) and the system of representation is strongly malapportioned. The choice of these two combinations is not arbitrary—there are strong theoretical and empirical reasons to suggest that high interregional inequalities and malapportionment go hand in hand (Reference Ardanaz and ScartasciniArdanaz and Scartascini 2013; Reference Beramendi and RogersBeramendi and Rogers 2016).Footnote 8

In the case of low inequality and low malapportionment, in which regional income and regional income distributions are fairly similar across the federation, this creates favorable conditions for the emergence of programmatic platforms that bring together the poor in both rich and poor regions, thus structuring politics along class lines. Similarly, the wealthy have stronger incentives to ally with their rich counterparts in other regions than to build cross-class regional coalitions to protect their regional tax base. This dynamic is reinforced by the system of representation that facilitates the emergence of strong parties. As a result, standard programmatic conflicts over interpersonal redistribution (t) are at least as important as, and usually more important than, distributive conflicts between territories over revenue sharing (T) even in federations.Footnote 9

The incentives and political leverage of both elites and less affluent citizens are very different under conditions of high interregional inequality and high malapportionment. When interregional inequality is high, regions differ both in their average income and in the incidence of distributive conflicts within their boundaries. At the same time that higher levels of inequality polarize preferences, malapportionment empowers local elites, particularly in poorer, less populated areas, to stand by their first preferences in national fiscal bargains because they have valuable votes in the legislature (Reference SoaresSoares 1973; Reference Gibson and CalvoGibson and Calvo 2000).

As inequality between regions increases, wealthy elites in the rich region grow wary of two things: excessive interpersonal redistribution and large-scale interregional transfers, both of which expected to be funded through taxes drawn primarily from their region. The former would come about if a coalition of poor citizens across all regions coordinates to increase fiscal effort at the federal level, and the latter if the rest of the federation agrees to implement a large-scale system of transfers between regional governments. As captured in Figure 2, the rich among the rich share the concern over t with the rich among the poor, and they share the concern over T with the poor citizens in their own region who are worried they will lose a share of their region’s resources to other areas of the federation.Footnote 10

Given that high levels of malapportionment privilege the voice of political elites from less populated regions, what is the likely coalitional outcome? The internal division between low-income citizens across regions limits the feasibility of a coalition for large-scale interpersonal redistribution at the federal level. Exploiting this fact, and the political leverage of economic elites in less developed areas, the rich among the rich reach an agreement with the rich among the poor to articulate the fiscal structure around a disproportionate use of interregional transfers relative to interpersonal redistribution. At the expense of the welfare of low-income citizens in low-income areas, this agreement features several advantages: first, it allows the political elites in poor areas to capture rents and sustain effective clientelistic strategies that perpetuate them in office. These strategies in turn operate as a substitute for the welfare state and mute the demand for redistribution via large-scale public goods and welfare state transfers (Reference AltamiranoAltamirano 2015); second, they protect the income of a large share of citizens in the rich region from the tax implications of large-scale redistribution; third, the minimization of t implies that the middle- and high-income citizens of the rich region become net beneficiaries of the system, further undermining the feasibility of a national pro-redistributive coalition (Reference WibbelsWibbels 2017). As a result, the emerging fiscal structure under conditions of high interregional inequality and high malapportionment features a bias toward interregional transfers and much lower levels of overall fiscal redistribution through interpersonal transfers.Footnote 11

Our central argument is that this particular combination of high interregional inequality and high malapportionment differentiates Latin American federations from other unions in the world that have developed larger systems of fiscal redistribution. The remainder of the article explores this contention in two steps. First, we present a macro-comparative analysis showing that interregional inequality and legislative malapportionment have a consistent negative relationship with redistributive effort in a global sample. This analysis also helps place Latin American federations in context: they emerge as a cluster of their own because of their specific combination of high interregional inequality and high malapportionment. Second, we present an in-depth analysis of the experiences of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico that highlights the working of our core theoretical mechanisms.

Macro-Level Empirics: Placing Latin American Federations in the Global Context

The central parameters in our theory link the territorial structure of inequality and malapportioned political institutions to low redistributive effort in federations. In this section we show broad cross-national support for this argument and position the Latin American federations as a distinct cluster in a global context. To conserve space, we provide the regression results and discussion of the large-N analysis in appendix Table A2.

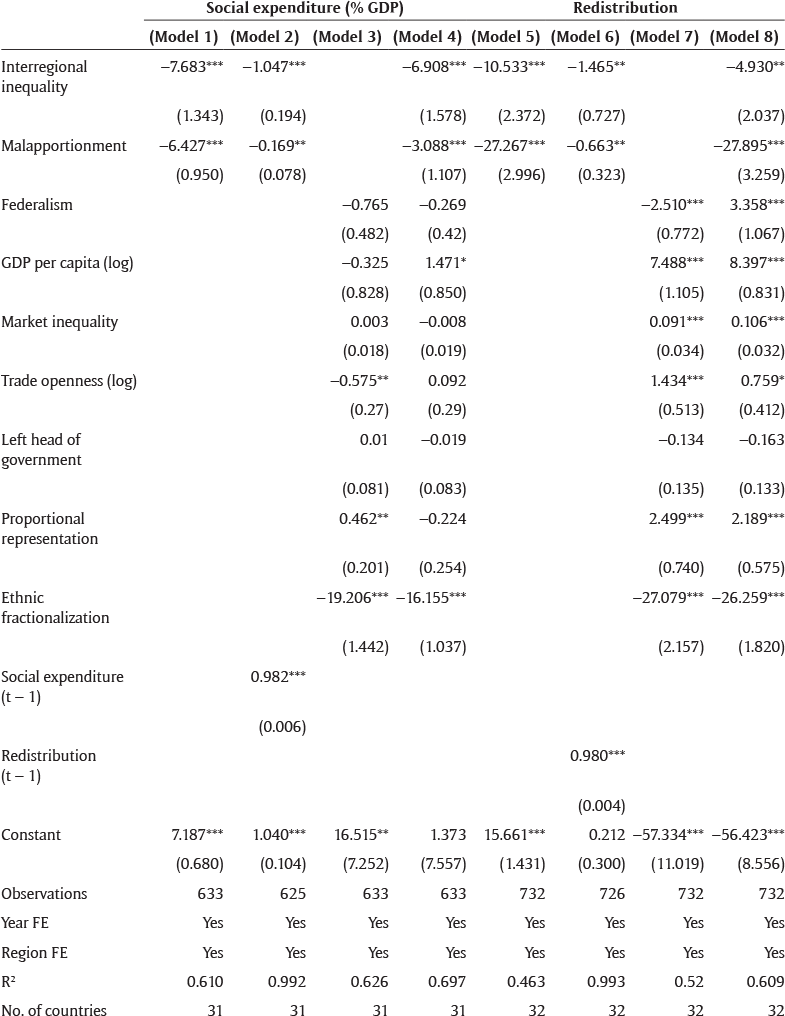

Our regression estimates show the relationship between the best-available cross-national measure of interregional inequality, the Gini coefficient of region-level gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and two indicators of interpersonal redistribution (t): social expenditure (percentage of GDP) and fiscal redistribution (percentage difference between the pretax and transfer “market” Gini and the posttax and transfer “net” Gini coefficients on national household income inequality) (Reference SoltSolt 2009). In this sample of thirty-two countries, the results show that interregional inequality and legislative malapportionment (upper and lower house) are strongly and consistently related to lower redistributive efforts. Online appendix 2 shows Latin American federations have extreme values on both variables; this separates them from their federal counterparts in OECD nations.Footnote 12 We demonstrate the robustness of these predictions by including important control variables, time and region fixed effects, and adjusting for predictable challenges to time-series cross-sectional data.Footnote 13

Including interregional inequality and malapportionment in the models of interpersonal redistribution also adds considerable explanatory power. To show this, we plot the predicted and actual levels of redistribution for our sample in Figure 3. Our three country cases are systematically overpredicted (especially Argentina) in models that do not include interregional inequality and malapportionment. For example, Figure 3 (left) shows that Argentina is expected to reduce market inequality by approximately 15–18 percent on the basis of standard independent variables predicting redistribution. The actual reduction in market inequality in Argentina is 3–4 percent. With interregional inequality and malapportionment included, our cases are predicted more accurately by the model (Figure 3 right). These figures show that the territorial structure of inequality and regional representative structure are important predictors of redistributive efforts.Footnote 14

Figure 3: Comparison of models predicting redistribution. (Residuals predicted from Model 4 (Figure 3 left) and Model 8 (Figure 3 right) in appendix Table A2).

These empirical analyses are necessarily preliminary and correlative given the endogenous relationship between the territorial structure of inequality and institutional selection predicted in our theory. However, the results provide a reasonable basis for assessing the cross-national association between these variables, and for placing the Latin American federations in comparative context.

Distributive Tensions and Fiscal Structures in Latin American Federations

Having established the broader theoretical and empirical links between the territorial structure of inequality, regional representation, and redistributive effort, we move to a more in-depth analysis of cases that exemplify these relationships. We constructed a new data set of region-level inequality to characterize the redistributive pressures in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico and how each is influenced by representative structures that privilege the less populated regions of these nations. The figures in this section are intended to be directly comparable to our theoretical diagrams in Figure 2. For each case, we calculate levels of regional inequality (measured by the state or province-level Gini coefficient of income per capita) and regional median income per capita to assess patterns of distributive pressures over time. Importantly, we are showing latent preferences for redistribution (in pretax inequality) and not redistribution itself. From a theoretical perspective, we are trying to explain whether citizens and politicians within these nations would seek interpersonal or interregional equilibration of income, and how those preferences are represented in policy making.

We find consistent evidence that the territorial structure of inequality favors interregional over interpersonal government redistribution. In all three nations, legislative support should be higher for intergovernmental transfers to equilibrate regional income levels than for central policies to reduce interpersonal inequality. Within these cases, however, are different inequality patterns that drive distinct redistributive coalitions. Thus, these nations fit Mill’s method of agreement, whereby cases with different political traditions and histories result in similar distributive outcomes as a result of the common structural factors of territorial inequality and legislative malapportionment. In Brazil and Mexico, rich states are more equal and poor states more unequal. Malapportionment in Brazil strongly favors the sparsely populated Amazon and poor Northeast, and governors in rich, powerful states have therefore fought to keep resources inside their borders. In Mexico, the malapportioned senate also drives allocations to less populated (but not necessarily poor) regions, and tax centralization and expenditure decentralization keeps demands for interregional transfers high. In Argentina, extreme malapportionment favors interior regions with strong preferences for interregional redistribution.Footnote 15

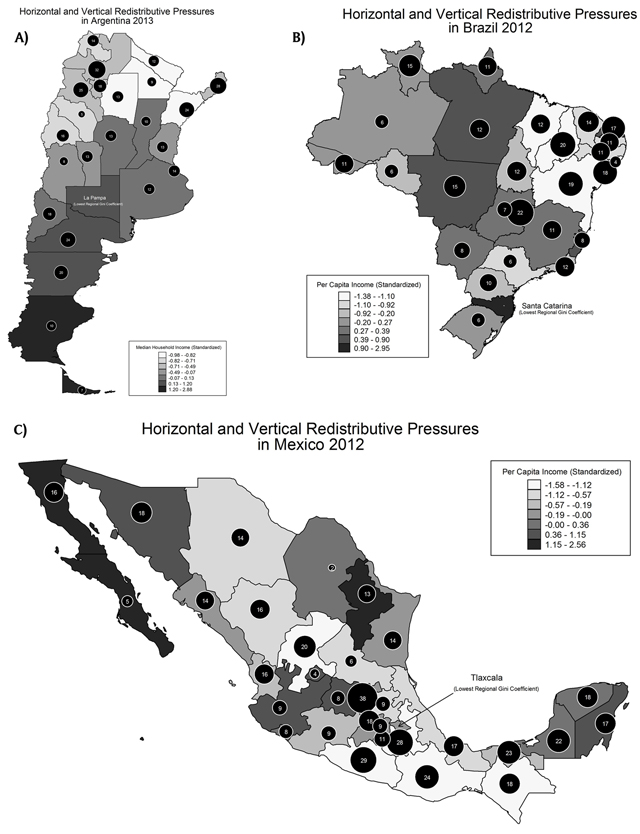

Figure 4 maps the configuration of region-level Gini coefficients and regional median incomes for the most recent available year for Argentina (2013), Brazil (2012), and Mexico (2012). For each country, we calculated these values using surveys conducted by their national statistical agencies. The reported Gini coefficients for Brazil (from the Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios) and Mexico (from the Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares) are calculated per equivalent adult, on the basis of the following equivalence scale: YE = Y * [.5 + (n – 1) * .25], where n is the number of members in a household and Y is income. Argentina’s Encuesta Permanente de Hogares (EPH) is not a national survey but covers only the largest cities in the country. Despite this limitation, the EPH includes one city in each province, and Argentina is highly urbanized, allowing for generalizations of provincial distributions.Footnote 16 Argentina’s values are calculated on a per capita household basis, given the structure of the data available for that nation.

Figure 4: Distributive maps of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico.

While these data are certainly imperfect—they are not directly comparable across countries—they do provide reasonable estimates of national income spreads that are comparable across regions within the nation and over time.Footnote 17 To demonstrate patterns, we use descriptive statistics, figures and tables, and historical analysis of high-profile social policies. In doing so, we cannot provide a full account of the range of redistributive policies enacted in these nations, nor can we fully address differences in regional tax capacity, which may help explain some differences in redistributive effort across regions.Footnote 18

The median income of the state or province is indicated by the shading of the territory. The income level of the country as a whole is standardized so that any state with income greater than 0 is richer than the average. Intraregional inequality is indicated by the size of the circles overlaid on the region and the number listed inside the circle. The circles in Figure 4 are scaled relative to the region with the most even income distribution in that year: La Pampa (Argentina), Santa Catarina (Brazil), and Tlaxcala (Mexico). The numbers inside the circles represent how much larger, in percentage difference, the regions are in relation to La Pampa, Santa Catarina, and Tlaxcala.

The patterns of territorial inequality in the three nations are distinct. According to our logic, in Argentina voters in the richer provinces of the federal capital of Buenos Aires, Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego, and La Pampa should be less willing to provide funds to the poorer regions in the northern interior (lighter shades in Figure 4). Importantly, the largest circles are not exclusively in the poorer provinces. Certain wealthy provinces, such as Chubut, Neuquén, and Rio Negro would benefit from interpersonal redistribution but not progressive interregional transfers.

At the same time, poor provinces are sharply divided, with several of the poorest provinces (e.g., La Rioja, Chaco) consistently showing the lowest levels of inequality while others (e.g., Misiones, Corrientes, Salta) have the highest levels. Interpersonal and interregional redistributive pressures in Argentina work at cross-purposes: the provinces that would benefit from an expansion of centralized interpersonal redistribution (t) are not necessarily the same ones that would gain from interregional redistribution (T).

The Brazilian map shows that Northeastern states are both the poorest and the most unequal. Although there is a clear analogy between the Brazilian Northeast and the Argentine interior provinces on the grounds of their income levels, the interests of their voters regarding interpersonal redistribution diverge. Brazil’s South and Northeast have clear conflict on the desirability of t and T, both of which would constitute an income transfer away from São Paulo. In Mexico, the map shows a geographic divide of rich and relatively equal states in the north and poor and unequal states in the south. We find considerable variation in the level of inequality across states that in the Mexican case are negatively correlated with regional income.

The same information provided in the maps is presented in scatterplots in Figure 5 that denote the size of each region according to the sum of seats it holds in both houses of the federal legislature for the first and last years of each country’s data sample.Footnote 19 These charts can be directly compared to the hypothetical distribution of preferences described in Figure 2. Each chart in Figure 5 can be divided into quadrants depending on whether regions are above or below the median national income (indicated by the dashed line crossing 0 on the x-axis), and are characterized by higher or lower inequality than the national level (indicated by the dashed line on the y-axis). Regions in all three cases cover all quadrants, but very few observations are in the upper-right corner, characterized by poor voter preferences for high t and low T. The missing upper-right quadrant (indicating states with strong demand from poor voters and resources available to fund social transfers) is one possible reason interpersonal redistribution is low in these countries. In wealthy countries with rich but unequal states, such as California and New York in the United States, representatives from these areas often take the lead in driving legislative initiatives for interpersonal redistribution.

Figure 5: Redistributive pressure by total seats. (Seat counts include both upper and lower house apportionment).

In all three cases the available evidence suggests that coordination of the poor in favor of interpersonal redistribution is difficult given the territorial distribution of inequality. Figure 5 shows that the bulk of regions in Argentina and Mexico are in the bottom quadrants. In these quadrants, poor voters have weaker preferences for t, in relative terms, than seen among poor voters in the unequal regions in the top quadrants. In both countries, the majority of seats are on the left side of the figure, indicating that most are relatively poor regions with a strong preference for T from both rich and poor voters. Brazilian states (and seats) cluster more in the bottom-right and top-left quadrants. In the top-left quadrant, the poor voters would prefer high t and T. The poor voters in the bottom-right quadrant should oppose T and have relatively weak preferences for centralized t. Brazil’s territorial structure of inequality suggests the possibility of strong polarization among relatively rich and equal regions that prefer to minimize all centralized forms of redistribution, and relatively poor and unequal regions with poor voters that prefer high levels of both t and T.

Brazil’s federal bargain suggests a compromise between these polarized regions on the basis of moderate levels of interregional redistribution and low interpersonal redistribution. Consistent with this logic, Brazil has always been characterized by a vibrant federalism with a high degree of state autonomy that limits centralized redistribution. Much of the nineteenth century was dominated by the “politics of governors,” in which state leaders used their control of elections to the Brazilian National Congress to direct the national legislative agenda (Reference FenwickFenwick 2009). A distinctive feature of Brazil’s present fiscal structure is the state-controlled value-added tax (VAT), Brazil’s largest source of revenue.Footnote 20 Governors in Brazil have been adamant about retaining control over indirect taxation, even during times of military rule (Reference FalletiFalleti 2011). Brazil’s system of revenue sharing and federal expenditure disproportionately favor the less populated states, leading to a perception that the Brazilian federation is highly redistributive. However, control of the VAT by states limits these tools. Given large disparities in income and the concentration of industry in a few regions, the VAT counteracts the compensatory efforts made by the federal government through its revenue-sharing and transfer formulas (Reference Ter-MinassianTer-Minassian 2012).

In Argentina, there is always a large coalition of states that would presumably press for interregional redistribution (those seen on the left side of the dashed lines in Figure 5) (Reference GonzálezGonzález 2012). Several large provinces, including Buenos Aires and Córdoba, sat right at the median level of income in 2013 and were below the median in 1995. These large, productive states have some incentive to join with other relatively equal low-income provinces such as Chaco and Formosa to increase interregional transfers.Footnote 21 These distributive pressures have changed somewhat in recent years, however. Between 1995 and 2013, the federal capital (Buenos Aires) became wealthier relative to the national median and more equal than the national average. Other large provinces have also become comparatively more equal, resulting in low demand for interpersonal redistribution throughout the time observed. The resulting distributive scenario in Argentina is described by Artana and colleagues (Reference Artana, Cristini, Moskovits, Bermúdez and Focanti2010, 9): “There is, then, a federal government with powers and demands bounded by a marked regional redistribution; however, demands for personal redistribution do not have a clear arena for expression” (our translation).

Public expenditure in Mexico has very limited effects on its income distribution. According to estimates from the World Bank, most government programs in Mexico—with the exception of elementary education, conditional cash transfers from Progresa/Oportunidades and Procampo, and the health clinics of the Ministry of Health—are in fact regressive (World Bank 2005). The territorial structure of inequality helps explain these spending patterns. A large group of states have successfully blocked efforts at centralized functional redistribution, because these states are internally more equal than the country as a whole (shown in the lower half of Figure 5), while favoring the use of interregional transfers to reduce regional inequality, because they are poor relative to the national average (shown in the bottom left quadrant of Figure 5).

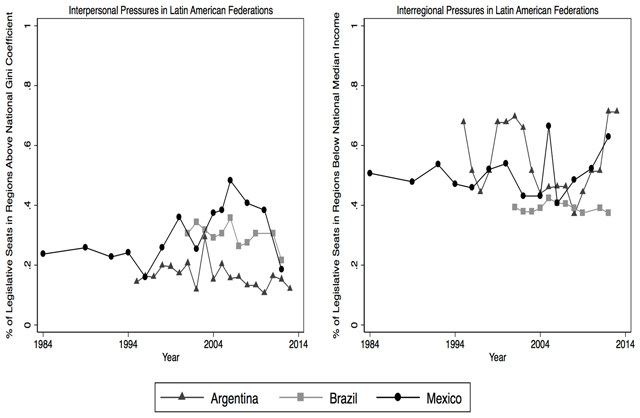

Figure 6 illustrates interregional and interpersonal distributive pressures over time in these three cases. For each year, we calculate the percentage of all legislative seats held by regions above the national Gini coefficient as a rough proxy for poor voter preference in favor of interpersonal redistribution (we assume that rich voters always seek to minimize t). These values are shown at left in Figure 6. The panel on the right plots the percentage of seats held by regions below the national median income, indicating presumed rich and poor voter support in favor of interregional redistribution. In all three cases, the seat share in favor of interregional redistribution (right) is significantly higher than that for interpersonal redistribution (left). The seat share theoretically in favor of interpersonal redistribution is quite low (40 percent or less) in all cases except Mexico in 2005, where support neared 50 percent.Footnote 22 Support for interregional redistribution is consistently high in Argentina and Mexico, most often above 50 percent of seats in both chambers and sometimes above 60 percent. Theoretical support for T is higher than support for t in Brazil, but lower on average compared to Argentina and Mexico.

Figure 6: Redistributive pressures in Latin American federations over time. (Authors’ calculations using yearly survey data and upper and lower house seat counts).

These patterns of preferences for redistribution have been largely consistent over time in all three nations, reflecting stability in economic geography and in the political structure articulated around fiscal federalism. There has been little change in the architecture of fiscal federalism in Brazil over the past three decades, despite repeated calls for reforms. The relative stability of the territorial structure of inequality provides one explanation for this impasse. While social spending increased in Brazil in recent years under the leadership of the Workers’ Party, the underlying fiscal structure and distributive logic of the country persists. Tellingly, the most successful example of redistributive policy in Brazil, Bolsa Família, has had a large impact on poverty precisely because it delivers resources straight to mayors rather than through governors (Reference FenwickFenwick 2009). Opportunities to transform Brazil’s redistributive equilibrium have depended fundamentally on electoral opportunities to tear down existing state patronage networks linked to malapportionment (Reference BorgesBorges 2013).

Argentina’s fiscal federalism is characterized by volatility in both the profile of redistributive pressures and bargaining over the rules of the game. After a near breakdown of the fiscal system in 1988, the provinces agreed to share revenue according to fixed coefficients. This resulted in a very large interregionally distributive system, which also reflects the disproportionate representation of small provinces of the interior. Reforms following the fiscal crisis in 2001 revised the system of fixed transfers but resulted in larger transfers overall, preserving its basic structure (Reference Saiegh, Fiorucci and KleinSaiegh 2004). Argentina’s transfers system is arguably the most complex in the world and is strongly influenced by malapportionment (Reference GervasoniGervasoni 2010).

Figure 6 demonstrates that the number of seats in Mexican states that would likely favor greater interregional transfers spiked above 50 percent at several points in the 1990s. During this period the country witnessed rapid decentralization that increased interregional transfers to fund the devolution of education, health, and public works responsibilities to subnational levels. States with higher Gini values than the national average were stable (and low in number) until 2005 in Mexico, when they briefly neared 50 percent of the seat share. In the 2000s, according to the states’ assumed preferences, we should see greater efforts to redistribute income interpersonally through more progressive federal policies. Indeed, between 2003 and 2010 Mexico dramatically expanded its social security program Seguro Popular to include health care for informal-sector workers, including more than forty-three million affiliates (Reference Levy and SchadyLevy and Schady 2013). Similarly, the old-age program 70 y Más increased coverage to the entire country and lowered the eligibility age to sixty-five in the period 2008–2012. Progresa/Oportunidades also gained much more generous funding during the 2000s and continues to have significant effects on poverty, if not the education outcomes to which it is linked (Reference Levy and SchadyLevy and Schady 2013). The most recent data (2010–2012), however, suggest significantly higher demand for interregional redistribution and lower demand for interpersonal transfers.

National income inequality in Mexico changed little throughout the period 1984–2000. Hence, no relationship exists between inequality and decentralization in the country as a whole, as a “naïve” hypothesis linking income distribution and decentralization would suggest. The mapping of redistributive pressures suggests that decentralization and greater interregional redistribution increased in the 1990s as the group of states whose median voters were willing to press for interregional transfers increased its representation in the legislature. Equally relevant, expansion of redistributive social policies occurred in the 2000s under a rightist president, as national income inequality was falling from its highest levels in the late 1990s. The position of the states relative to the national level of inequality suggests a reason for this unexpected outcome. While national inequality may have fallen, this was driven by changes in only a few states (Reference Lustig, López-Calva and Ortiz-JuarezLustig et al. 2013). Those states that did not experience reductions in inequality in the 2000s became more numerous and thus better represented in the national legislature.

Legislative Barriers to Redistribution

In the figures throughout this article, we have shown consistent evidence that many states and provinces in Latin America’s federations do not have strong incentives to favor national level interpersonal redistribution. Because these regions are more equal than the nation as a whole, they would be net contributors to social policies to alleviate inequality in the most unequal regions. In these three nations, preferences for interregional redistribution are strong. Relatively poor states could benefit from transfers that could equilibrate regional income. Whether transfers operate according to this principle depends on the political logic of intergovernmental distribution. In all three cases, this mechanism is strongly shaped by legislative malapportionment.

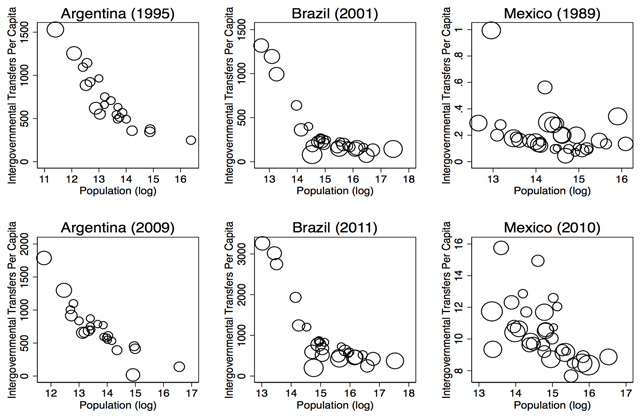

In theory, a focus on interregional transfers in Latin American federations may advance goals of income redistribution and poverty reduction by shifting resources to the neediest regions. If transfers are working this way in Latin America, income levels should be a strong predictor of intergovernmental transfers. However, Figure 7 shows that (low) population and related representation in the malapportioned legislatures are the strongest predictors of transfer levels in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico.

Figure 7: Income, population, and the distribution of interregional transfers. (Circles indicate the level of median household income by region).

In Figure 7, intergovernmental transfers per capita for each nation are plotted according to (logged) region-level population. The circle size indicates median regional income. In all three cases, but particularly in highly malapportioned Argentina and Brazil, transfers appear to follow a political rather than an economic logic. This is apparent even in Mexico, where malapportionment is limited to its Senate. If transfers were progressive, the smallest circles should be highest on the y-axis. Instead, the regions with the lowest populations receive the highest transfers, regardless of income level. In none of these nations do interregional transfers flow strongly to the poorest regions, thus limiting their potential to equilibrate income either interpersonally or interregionally.

Country studies describing the history of apportionment and transfers describe a political logic linked to concerns over interpersonal redistribution. The Brazilian revenue-sharing system has its origins in the 1960s, when the military governments tried to use redistributive interregional transfers to weaken governors in the industrialized states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro and strengthen conservatives in less developed provinces (Reference Díaz-CayerosDíaz-Cayeros 2006). Similarly, in Argentina, legislative representation was reapportioned according to the so-called Ley Bignone, for the namesake dictator, among other similar reforms, to limit the influence of the industrialized provinces around Buenos Aires. In both countries, military governments feared socialist influence in industrialized regions they feared would advance interpersonal redistribution (Reference EatonEaton 2001). The demographic shifts associated with industrialization (depopulation of the interior) have further reinforced these patterns and made malapportionment more efficient for political purposes.

There is ample evidence in the Brazilian literature that the northern states have been major recipients of redistributive transfers from the federal level of government (Reference Samuels, Mainwaring and GibsonSamuels and Mainwaring 2004). Importantly, Figure 7 shows that transfers flow not so much to the poor states as to the unpopulated states. The northern Amazonian states that are in the middle of the income distribution benefit the most from the transfer system. States—both rich and poor—have defended a highly decentralized fiscal federalism articulated around interregional transfers. The poor Brazilian states could have pressed for a centralized system of taxation, which would have presumably made them better off by increasing their access to federal government resources. Rent seeking linked to legislative malapportionment may thus limit redistribution. Local elites in poor and unequal states might discount the virtues of interpersonal redistribution because centralization of fiscal policies would undermine the local patronage networks they dominate (Reference Hagopian, Gervasoni and MoraesHagopian, Gervasoni, and Moraes 2009; Reference FenwickFenwick 2009).

Relatively recent transformations of Mexico’s fiscal federalism also reflect the dual logics of the territorial structure of inequality and malapportionment. Mexico created a comprehensive revenue sharing system in 1980. This system both guaranteed revenue to the states and stripped them of most of their tax collection authority. While this centralization of tax collection authority could ostensibly enable transfers across territories and people, states were guaranteed resources similar to their historical tax collection, and the allocation formulas predominantly weighted population and economic activity in the states. This meant that although fiscal transfers increased during the 1980s, transfers were not progressive (Reference Rodríguez-Oreggia and Rodríguez-PoseRodríguez-Oreggia and Rodríguez-Pose 2004).

Federations in Latin America redistribute income across their heterogeneous regions as part of the political coalition building of these nations that is intimately tied to legislative apportionment (Reference Gibson and CalvoGibson and Calvo 2000). The territorial structure of inequality and the institutional design of all three nations suggest that the continuity of this political distribution is strong and that its redistributive systems have not yet experienced profound transformations.

Conclusion

Latin America has the highest level of inequality of any region in the world, despite relatively high levels of income. Governments in the region have done very little, in comparative perspective, to redistribute income to alleviate these disparities. Major shifts in the ideological orientation in the Brazilian government and greater policy emphasis on reducing poverty in all three countries in the past decade offer some hope that this trend is reversing. However, despite the substantial strides by these governments to reduce poverty, the levels of inequality in these nations remain extremely high. While important, recent policy interventions in all three nations have not fundamentally altered their income distributions, and slowing growth in the region may lead to retrenchment that scales back these gains.

Dominant theories explaining the relationship between inequality and redistribution cannot account for continuity in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico’s limited response to income inequality (Reference Huber and StephensHuber and Stephens 2012; Reference Haggard and KaufmanHaggard and Kaufman 2008; Reference Kaufman and Segura-UbiergoKaufman and Segura-Ubiergo 2001; Reference Segura-UbiergoSegura-Ubiergo 2007). We offer one important explanation for this outcome—these nations have fiscal structures articulated primarily around politicized intergovernmental transfers rather than interpersonal income redistribution. We show that these fiscal structures are consistent with representation based around regions, the spatial distribution of income within and across those regions, and politicians’ assumed preferences based on those distributions. The territorial structure of inequality and the systems of representation in these federations thus systematically undermine class-based solidarity in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico.

Across the three cases, high interregional redistribution combined with very low levels of interpersonal redistribution are consistent with their preference structures that are linked to uneven regional income and regionalized national representation. In these federations local elites of less populated regions appear to have succeeded in securing their first preference—a political and fiscal system that transfers considerable resources to them interregionally, without engaging in large-scale interpersonal redistribution. Importantly, this institutional logic has not been eliminated with recent policy reforms. The evidence presented here shows strong persistence in these dynamics. Largely because of the legacy of inequality that is institutionalized within the system of political representation in these nations, we find reason to be skeptical that recent reforms and the current egalitarian climate reflect permanent and profound transformations.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Online Appendix. Barriers to Egalitarianism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.31.s1

Appendix

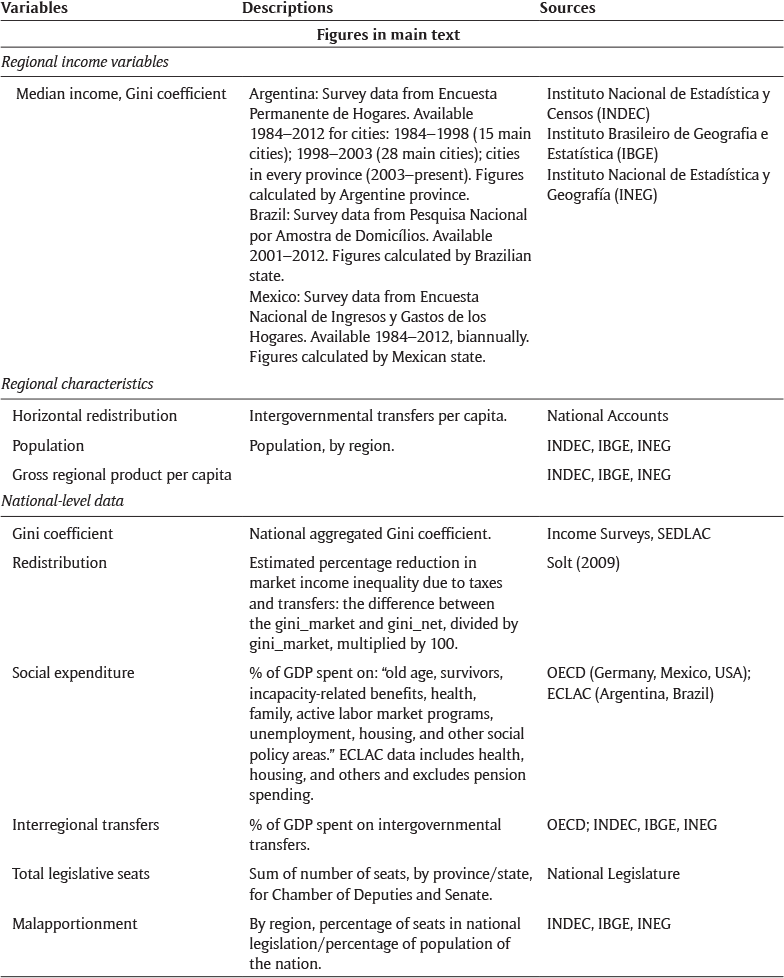

Table A1 Data sources and descriptions, main text.

In a cross-national sample of thirty-two countries, including our focus nations of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, we find strong evidence that both interregional inequality (one aspect of the territorial structure of inequality) and high levels of legislative malapportionment (upper and lower house) are linked to lower redistribution. Our measure of interregional inequality is the Gini coefficient of region level GDP per capita.Footnote 23 Malapportionment is measured as the sum of upper and lower house malapportionment (Samuels and Snyder 2003). We measure redistributive effort in two ways—with social expenditure (percentage of GDP) and “redistribution” from Solt (Reference Solt2009). Redistribution is measured, as in figure 1 in the text, as the percentage reduction in market inequality through government taxes and transfers. All data used in the analysis are described in online appendix 6.

In Table A2 Models 1 and 5 we show the relationship between interregional inequality and legislative malapportionment on redistributive effort with controls for year and region fixed effects. In Models 2 and 6 we add the lagged dependent variable to the specification with year and region fixed effects. In Models 3 and 7, we show the results of the models only estimated with standard controls that predict redistributive effort in research on OECD countries. In Models 4 and 8 we show the effects of our variables of interest in the full model. In all specifications interregional inequality and legislative malapportionment are associated with significantly lower redistributive effort.

Table A2 Effects of interregional inequality and malapportionment on redistributive effort, global sample 1980–2011.

Notes: All models estimated with panel corrected standard errors and are adjusted for AR(1) correlations except Models 2 and 5, which include the lagged dependent variable. All independent variables lagged one year.

***p < 0.01. **p < 0.05. *p < 0.1.

Including these variables adds significant explanatory value to the models, especially in those predicting redistribution. Importantly, federalism is shown to have an inconsistent relationship to redistributive effort in the sample. The results are primarily driven by region fixed effects. When region fixed effects are not included the relationship between federalism and redistributive effort is consistently and strongly negative. This occurs because of the large difference between redistributive effort in federations in affluent and the developing nations that are of central focus in our analysis. The cases we examine, along with developing federations including Indonesia and India, dramatically pull down the average redistributive effort of federations in a global perspective.

The models include year and region fixed effects to control for time and region-specific patterns. The models are estimated with panel corrected standard errors to adjust panel heteroskedasticity and spatial correlation. We include an AR(1) process to address serial autocorrelation in the dependent variables. We could not include country fixed effects because this would eliminate the estimates of institutional variables that are fixed over time. The measures of malapportionment and federalism are both fixed in this sample. The controls for proportional representation and ethnic fractionalization are also static. The relationship between interregional inequality and both redistributive effort dependent variables is robust to country fixed effects.

The control variables relate to the dependent variables in expected ways, particularly for the redistribution dependent variable in Models 6–8.Footnote 24 Richer countries have higher redistribution. The effect of economic development is much larger and more significant if region dummies are excluded. Ethnic heterogeneity has a consistent and strong negative effect on redistributive effort, consistent with Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003). This is an important variable to explain Brazil and Mexico’s redistribution, in particular. Market inequality and trade openness both have a positive relationship with redistribution. Proportional representation is associated with increased redistributive effort (Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2006). The results are not sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of any control variables.

Recalling our theory, interregional inequality is only one aspect of the territorial structure of inequality. The level of inequality within regions is also crucial because it can shape preferences of the rich and poor to form cross-regional coalitions. The results we present above are, accordingly, omitting an important theoretical variable for which we unfortunately lack enough data to do a similar large-N analysis. In online appendix 4 we show results for a very limited sample that includes data on both inter- and intraregional inequality and find very consistent results.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dong-wook Lee and Alma Bezares Calderon for top-quality research assistance. We also thank Robert Franzese, Lisa Piergallini, Rena Salaveya, Alejandro Bonvecchi, Oscar Cetrángolo, Nicolás Cherny, and the participants of the Politics of Redistribution Conference at SUNY Buffalo (May 2016) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.