Article contents

Quesnay's Tableau Economique: A Puzzle Unresolved

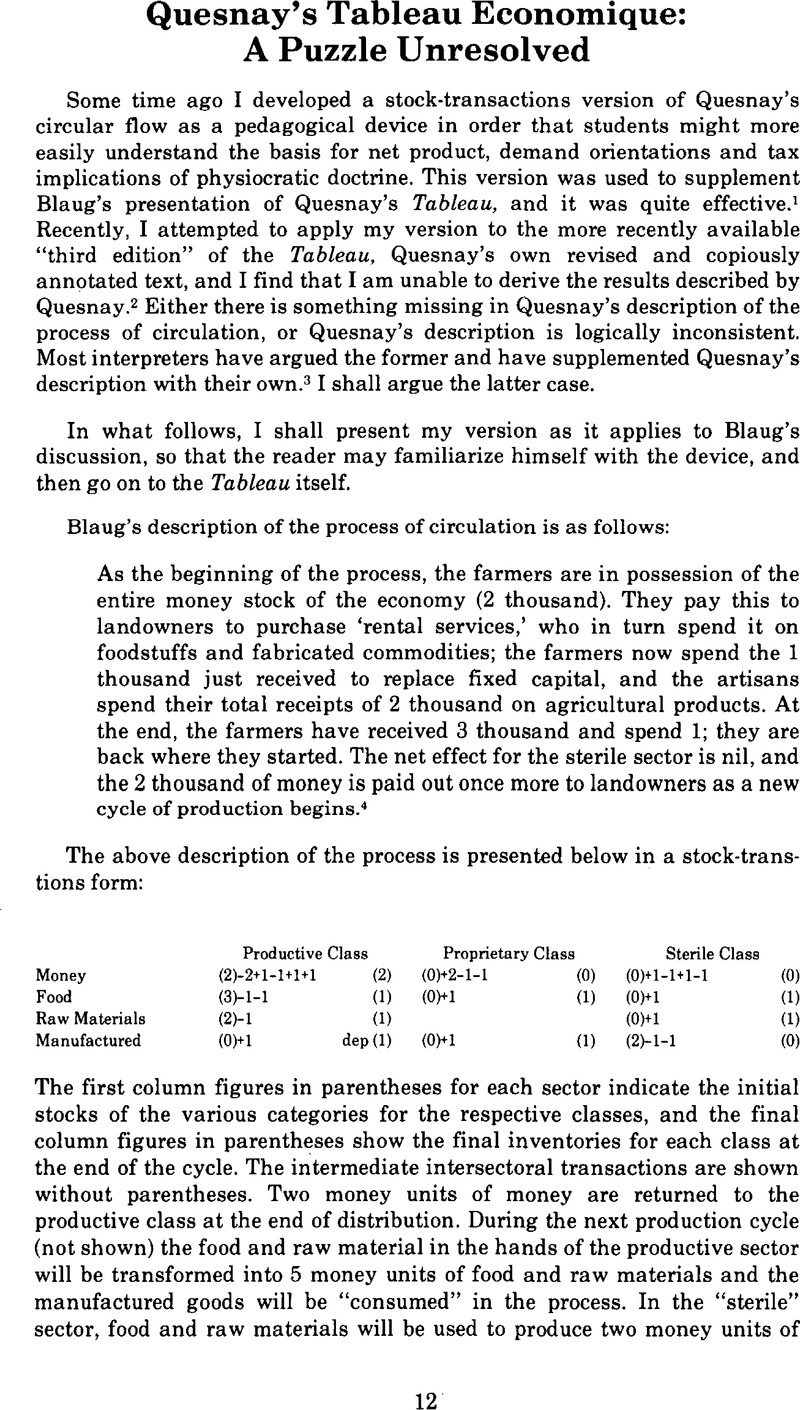

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1979

References

Footnotes & References

1. Blaug, Mark, Economic Theory in Retrospect (3rd ed.; London: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 24–29.Google Scholar

2. Quesnay, Francois, Tableau Economique, trans. and ed. Kuczynski, Marguerite and Meek, Ronald L. (New York: Augustus M. Kelly, 1972)Google Scholar.

3. Meek, Ronald L., The Economics of Physiocracy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard, 1963)Google Scholar devotes an entire chapter to problems associated with the Tableau (pp. 265–296)Google Scholar, so that the issues revived in this paper are not new. What is new is that they remain unresolved.

4. Blaug, , op. cit., p. 27Google Scholar.

5. Quesnay, , op. cit., table page (unnumbered)Google Scholar.

6. Ibid., pp. i–ivGoogle Scholar.

7. Meek, Ronald L., op. cit. p. 254Google Scholar, attempts to deal with this problem by assuming that the sterile class spends its advances on raw materials before the productive class makes payments to the proprietary class. The money necessary for payment to the proprietary class is thus available to the productive class. This may “solve” the problem of money flows, but then another problem develops with respect to product flows. Meek shows the sterile class transforming those same raw materials (in his example 1000) into manufactured goods having twice the value (2000 money units of manufactured goods). Once these two “prerequisites” are satisfied, he begins the “main” process and thus he has a solution.

8. In terms of the stock-transactions table the Money row is ignored and what remains is product flows and balances.

9. Such an example of apparent value-added is found in Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Cannan, Edwin (New York: The Modern Library, 1937), pp. 631–633Google Scholar, but as he correctly points out the apparent value added in manufacturing is nothing more than the cost of subsistence (or advances), during the period of production. Such advances must be in product not money, since workers cannot eat the latter. Hence we are brought to the point above in the text of this note. If 300 money units of money in the hands of the “sterile” sector are spent for 300 money units of product (as advances), the productive sector will not have sufficient advances to produce a total product of 1200 money units, since it requires 600 money units of food and raw materials to do so.

10. One possible solution is that the 300 money units of advances are spent by the sterile sector externally for raw materials to be transformed into manufactured goods, or alternately it merely buys manufactured goods externally with the advances. Either case would solve the puzzle, but they raise a new question of the dependence of the system on external trade in order to produce a sufficient net product. Meek, , op. cit., p. 283Google Scholar, relies on an external trade solution to the problem.

- 1

- Cited by