I. INTRODUCTION

Historians of economic thought have in the last twenty-five years shown an increased interest in analyzing visual representations of economic ideas (Klein Reference Klein and Rima1995; Ruccio Reference Ruccio2008; Blaug and Lloyd Reference Blaug and Lloyd2010a). Careful studies have analyzed the Marshallian cross diagrams (Humphrey Reference Humphrey, Blaug and Lloyd2010), the indifference curves and isoquants (Blaug and Lloyd Reference Blaug, Lloyd, Blaug and Lloyd2010b), the Phillips curve (Lipsey Reference Lipsey, Blaug and Lloyd2010), the Laffer curve (Middleton Reference Middleton, Blaug and Lloyd2010), the Lorenz curve (Kakwani Reference Kakwani, Blaug and Lloyd2010), circular flow diagrams (Backhouse and Giraud Reference Backhouse, Giraud, Blaug and Lloyd2010), the Stolper-Samuelson box (Thompson Reference Thompson, Blaug and Lloyd2010), and various other visualizations. In the same period, scholars of another interdisciplinary field—science and technology studies—began to cultivate an increased interest in visual representations. Most of these accounts emphasized that visualizing in scholarly realms is not about mirroring what is out there but about making certain aspects of the referent accessible and plausible for others. Eventually, visualizing was not portrayed as an ex post add-on to making scholarly accounts but as an inherent part of making natural and social science (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2006; Daston-Galison Reference Daston and Galison2007; Coopmans et al. Reference Coopmans2014). Yann Giraud (Reference Giraud2010) and Giraud and Loïc Charles (Reference Giraud and Charles2013) have pointed out that visual representations played a pivotal role in the rivalry among economic experts in the US from the 1920s until the mid-1940s. However, accounts about visual representations of economic ideas have, so far, been concerned only with static illustrations, figures, and diagrams. This article focuses on the history of the first economics film in order to show that visual presentation of economic ideas was not limited to static kinds of representation. Michael Polanyi’s economics film was a motion picture, a bold experiment that aimed to represent and spread certain economic ideas (Beira Reference Beira2014; Mullins Reference Mullins2014; Bíró Reference Bíró2017). And the way in which Polanyi portrayed these ideas offers an insight that goes well beyond interpreting a highly circumscribed episode in the history of economics.

II. TOWARDS THE FIRST VERSION

Michael Polanyi was among the high-achieving Jewish-Hungarian scientists who left Hungary in a double exile at the beginning of the twentieth century (Frank Reference Frank2009). He trained as a physician prior to World War I but soon shifted to physical chemistry and was always something of a polymath with very broad interests. After fleeing from first Budapest (1919) and then Berlin (1933) due to emerging authoritarian regimes, Polanyi eventually found an intellectual home at the University of Manchester. Having a secure position as head of a chemistry laboratory and working with several colleagues enabled Polanyi to digest his personal trauma and to understand why he needed once again to leave his life in Berlin behind. Polanyi turned to the social sciences in order to be able to find answers for the two most pressing questions of his time: Why had fascism and Soviet communism become so appealing and influential? Why did democracies fail to stop this process? All of Polanyi’s work in the social sciences and philosophy can be interpreted as his various attempts to find answers to these questions, and to provide a better foundation for democratic, liberal alternatives to fascism and communism.

Polanyi’s first serious treatment of economic matters was “U.S.S.R. Economics: Fundamental Data, System, and Spirit” (Reference Polanyi1935a), which was a critique of Soviet economic statistics. Despite its title, this account was not primarily about economics per se but statistics. Polanyi was concerned to show the philosophical and ideological entanglements of Soviet statistics. At the same time in the 1930s, economic planning was becoming increasingly popular in the United Kingdom. Many believed that what they read and saw in the official statements of the Soviet Union was an accurate portrayal of social and economic conditions. Polanyi worried about this distressing tendency in his newly found home. He had visited Soviet Russia (first in 1928) and had seen how the people lived there. Polanyi recognized a discrepancy between Soviet economic reality and its representation. He knew that the increased popularity of economic planning on British soil threatened to bring in the philosophical and ideological entanglements of the Soviet system. Perhaps the best example to show the popularity of economic planning in England is provided by Colin Clark. Clark started to write his A Critique of Russian Statistics (Reference Clark1939) to counter Polanyi’s argument in “U.S.S.R. Economics” (Reference Polanyi1935a), but, during his writing of the book on his voyage from England to Australia, he realized that he agreed with Polanyi. There was, of course, an array of ideas about economic planning, and milder versions are not to be enmeshed with radical policies entailing the planning of production and commerce. Daniel Ritschel gave an extensive treatment to this colorful palette of planning in his The Politics of Planning (Reference Ritschel1997).

Unlike his socialist brother, Karl Polanyi, Michael was a devoted liberal and as such he made great efforts to map what was going on in the changing terrain of liberal ideas. After coming to England in 1933, he built an extensive international network of liberal intellectual friends and participated in the notable liberal gatherings of the time. He showed the first version of his film at the Walter Lippmann Colloquium (1938) and was an original member of the Mont Pèlerin Society (1947). Polanyi continued corresponding with old friends from the continent, including Toni and Gustav Stolper, an economic journalist couple he had met during his Berlin years (1922 to 1933). The Stolpers’ oldest son, Wolfgang, later became known as a co-author of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. After becoming familiar with the contemporary streams of liberalism, Polanyi realized that he did not completely agree with any of these and he needed to articulate his own version of economic liberalism. Even though he became a regular correspondent with Friedrich Hayek and a popularizer of John Maynard Keynes, he was adamant about making clear his own economic ideas. But he knew that he could not do this without allies. Polanyi’s most important allies with whom he discussed economic topics were Toni Stolper and the Manchester School liberal economist John Jewkes. Jewkes worked at the University of Manchester and established a research group sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation (Tribe Reference Tribe2003). Jewkes and Polanyi quickly became friends after Polanyi’s arrival in England in 1933. Jewkes encouraged Polanyi’s studies in economics, read his manuscripts, and advised him about his film project. He also shared his experience working with the Rockefeller Foundation, and this proved to be vital for the burgeoning film project. But the contemporary economic downturn in the mid-thirties did not leave scholarly experiments untouched. These projects were likely adapted to the extraordinary economic and social environment.

The Great Depression of 1929 to 1933 challenged not only economies but also all those with economic expertise. As scarcity grew, discourses about the economy became increasingly politicized and the boundaries between political propaganda and economic expertise blurred. Proponents of various positions realized that the struggle of explanatory traditions would be decided by their ability to draw the attention of the general public. Reaching out to the uneducated masses in the cheapest way possible became a pragmatic scholarly strategy. The reduction of available material and human resources during the Great Depression and then World War II gave new impetus to mass education experiments. Perhaps the best known of these experiments, Otto Neurath’s Isotype (Vossoughian Reference Vossoughian2008; Burke et al. Reference Burke2013; Doudova et al. Reference Doudova2018; Nemeth Reference Nemeth, Cat and Tuboly2019), was both a source of inspiration and a threat to Polanyi’s own endeavors.

Polanyi was inspired by the success of Isotype. It was a visual method that managed to carry theoretical and practical commitments to the masses. But he also considered Isotype a threat because it carried socialist leanings, which he regarded as dangerous for liberal democracies. Not surprisingly, the propaganda potential of Isotype was soon recognized by the big players in propaganda. Otto Neurath was invited to Moscow to establish the All-Union Institute of Pictorial Statistics of Soviet Construction and Economy (IZOSTAT) in 1931. While the collaboration proved to be short-lived (ended in 1934), the Izostat Institute continued to spread propaganda about the great economic and social progress of the Soviet Union until 1940. After moving from the Netherlands (where he previously founded the Mundaneum Institute) to England, Neurath established another institute in Oxford (1942), which produced propaganda materials for the British Ministry of Information (Tuboly Reference Tuboly and Rima2019). Isotype was used for propaganda filmsFootnote 1 and book seriesFootnote 2 in the 1940s to strengthen the faith in the Allied Powers and to promote the British welfare state.

Isotype had the potential to become the economics pauperum Footnote 3 of the socialist world. Polanyi decided to make one for the liberal world and Western democracies. He very succinctly summarized his personal vision as “democracy by enlightenment through the film” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1935c, p. 1). He outlined a plan to establish centers of economics education, using his film to teach people who would become “a nucleus of educated people” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1937b, p. 13) carrying futher what they had learned. Polanyi envisioned that “a calm light would spread out” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1936, p. 4) to the society at large, radiating a kind of social consciousness eventually “encompassing all our activities” (ibid., p. 5), and which, by doing so, would revitalize liberalism and Western civilization.

Interpreters (Scott and Moleski Reference Scott and Moleski2005; Nye Reference Nye2011; Jacobs and Mullins Reference Jacobs and Mullins2015; Beira Reference Beira2016; Bíró Reference Bíró2019) agree that, for Polanyi, the film was not only a tool representing economic ideas. It was also a way of inducing large-scale social change. Polanyi put himself on a mission to spread his economic ideas using the film as a vessel. He wrote a number of pieces explaining what he intended to do, how he planned to do it, and the reasons behind his project. The most important of these several pieces are “Notes on a Film” (Reference Polanyi1936), “On Popular Education in Economics” (Reference Polanyi1937b), “Visual Presentation of Social Matters” (Reference Polanyi1937c), and the “Historical Society Lecture” (Reference Polanyi1937d).Footnote 4 These writings (some of which were public lectures) had a very similar central argument, which can be summarized as follows. Social matters cannot be seen in a physical sense, which makes it harder for those people without advanced training to understand them and to make informed decisions about them. These matters could and should be made visible for laypeople to reach a better understanding. Better understanding was necessary in order to promote social consciousness and to make it harder for people to misguide others. The first responded to the urge to know how our everyday deeds fit into a larger scheme. The second recognized the fact that fallacies usually spread faster and farther than well-founded statements. Better understanding was, in Polanyi’s view, necessary to save liberalism, democracy, and Western civilization, which were under assault in the West by both internal and external forces. The internal forces were extreme skepticism and utilitarianism, and the external forces were the authoritarian patterns of exercising power coming from countries under dictatorship. Polanyi aimed to achieve better visibility and therefore better comprehensibility with his film in order to stop the undesirable tendencies threatening what he perceived to be the Western acquis civilisationnel.

The content of the film mirrored Polanyi’s appreciative reading of Keynesian economics, but it was not a simple remake of Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Reference Keynes1936). When Keynes’s masterpiece came out, Polanyi was already working on his film, which admittedly was influenced by Keynes’s two earlier contributions, A Tract on Monetary Reform (Reference Keynes1923) and A Treatise on Money (Reference Keynes1930). When Polanyi read the General Theory around Christmas in 1936, he recognized the new book to be closely linked to Keynes’s previous contributions as well as to his own film-in-development through how these scholarly pieces similarly addressed the trade cycle.

Polanyi’s film began by portraying the circulation of goods (and services) and money. It showed how individual purchases and savings have become part of a larger scheme, and, by doing so, affected the whole economy. As the narrative advanced, the viewer was taught about what was happening on both a micro and macro level when an economic boom or bust occured. The film ended by showing how to fight recession by pumping more money into circulation solely by monetary means. Keynesian economic policies embraced several fiscal elements ranging from infrastructural investments to public works. But Polanyi thought that these policies did more harm than good for at least three reasons. First, they were impeding the natural working of the market mechanism and, by doing so, were fostering changes that were rather anti-market than pro-market. Second, they favored certain people and corporations at the expense of others and thus were not completely fair. And third, they required discretionary decisions, which too often led to corruption. But can a Keynesian policy without fiscal provisions be developed? Polanyi’s solution was a kind of neutral Keynesianism, which embraced state intervention into the economy but only by monetary means. He proposed making a budget deficit from tax remissions when it was necessary to pump more money into circulation. According to Polanyi, this would boost economic recovery in a neutral way—that is, without favoring any group at the expense of others.

Regarding the possible artistic inspirations for Polanyi’s film, only a speculative explanation can be given. He was familiar with Neurath’s Isotype using “amount pictures” or “number-fact pictures.” However, his old friend, Oscar Jaszi, called his attention to other visualizations of economic matters, including Norman Angell’s The Money Game: How to Play it: A New Instrument of Economic Education (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1935b) and an unspecified diagram of Franz Oppenheimer’s Mehrwert (added value) theory. Angell’s Money Game (Angell Reference Angell1928) visualized the economy by using thematic illustrated cards and offered a playful way to learn about economic mechanisms. Oppenheimer, like other geoist thinkers, thought that the value coming from the land should be equally distributed between members of the society and that people should own the value they add through production. It is unclear which Oppenheimer diagram Jaszi meant and whether Polanyi followed up on Jaszi’s suggestion to check out Angell and Oppenheimer. But it seems likely that the most important artistic inspiration came from a second-hand summary of a somewhat similar project of James D. Mooney, president of General Motors Overseas (1920 to 1944).

Mooney developed and patented several apparatusesFootnote 5 in the thirties and forties, which aimed to give “physical analogies” of what was happening in the economic realms of households, corporations, and national economies. Polanyi was informed about Mooney’s parallel endeavors by Charles V. Sale, an official of the Rockefeller Foundation, who was in touch with Mooney. Sale sent Polanyi an excerpt of one of Mooney’s letters, stating that “I feel that motion pictures of the apparatus, accompanied by synchronised spoken explanation, and reinforced if necessary by simplified charts and diagrams in ‘moving cartoon’ style, offer the best means of large-scale presentation” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1937a, pp. 1–2). In the Polanyi archival materials, there is a small sketch, apparently made by Polanyi, on the back of a page of Sale’s letter. The placement of the sketch suggests that Polanyi likely drew it just after reading the letter. And this sketch succinctly summarizes the plot of his film premiered one year later.

The sketch (see Figure 1) contains a circle with smaller rectangles and some arrows. Some of the rectangles and arrows are inside the circle, but others cross the circumference. The figure contains several letters. There is a formula on the right of the diagram containing some of the letters. Polanyi provided no legend explaining what he meant by each letter but a likely explanation can be given.

Figure 1. Polanyi’s Sketch on the Back of a Page of Sale’s Letter

The circle with two arrows is a cycle and probably represented the circulation of income (i) and expenditure (e). The rectangle inside seems to be the banking sector (B) having multiple relations with monetary circulation. Inflows are most likely savings (s) and ageing (a),Footnote 6 outflows are profit (p) and additional units of capital (c). The rectangle on the circle’s circumference seems to be factories (F) receiving expenditure (e) and paying income (i) in the cycle, and receiving profit (p) and paying ageing (a) in respect to the banking sector (B) inside. Polanyi’s formula suggests that the amount of money at a given time (from 0 to time t) is the integral of (additional units of capital (c)—ageing (a)—saving (s)). While the compact graphical way of representation changed, this system undoubtedly became the backbone of Polanyi’s film.

Polanyi developed three elements from Mooney’s description of the desirable method forwarded to him by Sale. He used motion picture technology, synchronized spoken explanation (he developed sound for his film), and a cartoonish style. However, there are at least three reasons to think that he was actually not using Mooney’s blueprint. First, the time frame does not fit. When he received the letter from Sale in 1937, he had already been working on his own film project for several years. Second, the scope of Polanyi’s project is different from Mooney’s. Mooney proposed filming the working of his apparatus; Polanyi proposed making a standalone film. And third, there are apparently differences in the content of their projects. Mooney developed a separate apparatus for each economic phenomenon he wanted to show, but Polanyi developed a film to show both the economic micro- and macrocosmos by using a single visual tool. Sale’s letter did not include details about the content of Mooney’s apparatuses, and there are no extant letters between Polanyi and Mooney about the content of these representations (or any other topic). Since most of Mooney’s economic apparatuses were patented in the 1940s when Polanyi had already completed not only the first but the second version of his film, the content of Mooney’s apparatuses could not have influenced him in the phase of development.

Polanyi’s visualization had common elements with Neurath’s Isotype (cartoonish style, simple diagrams), Mooney’s description of the desirable visual method (cartoonish style, synchronized spoken explanation, simple diagrams, use of film technology), and Angell’s board game (cartoonish style), but it also had several unique features. First, Polanyi used multiple representations for a represented element instead of a single representation (see Figure 2). All the other visual methods used a single representation to denote a represented economic phenomenon. Isotype even prohibited taking such a path by stating that “one [symbol] has to be like another so far as it gives the same details, and to be different from another only so far as the story it gives is different” (Neurath Reference Neurath1936, p. 28). In Neurath’s visual regime, one “puts into his picture only what is necessary” (ibid.) for the story to be told. Polanyi’s regime had more details than were necessary.

Figure 2. Multiple Representations of a Single Represented (Worker)

Second, Polanyi used changing representations instead of unchanging representations (see Figure 3). None of the other visual methods portrayed how one visual representation turns into another, except Polanyi’s. One might argue that the explanation for this is simple: there was no change of representations to portray because the other methods used only one set of representations. But it was more than that. It was uncommon to expose the flexibility of the applied visual representations to the audience. Flexibility of scholarly representations was not a thing to be exposed to the general public. Polanyi exposed it, intentionally and systematically.

Figure 3. The Representation of Economic Sectors Change before the Eyes of the Viewer

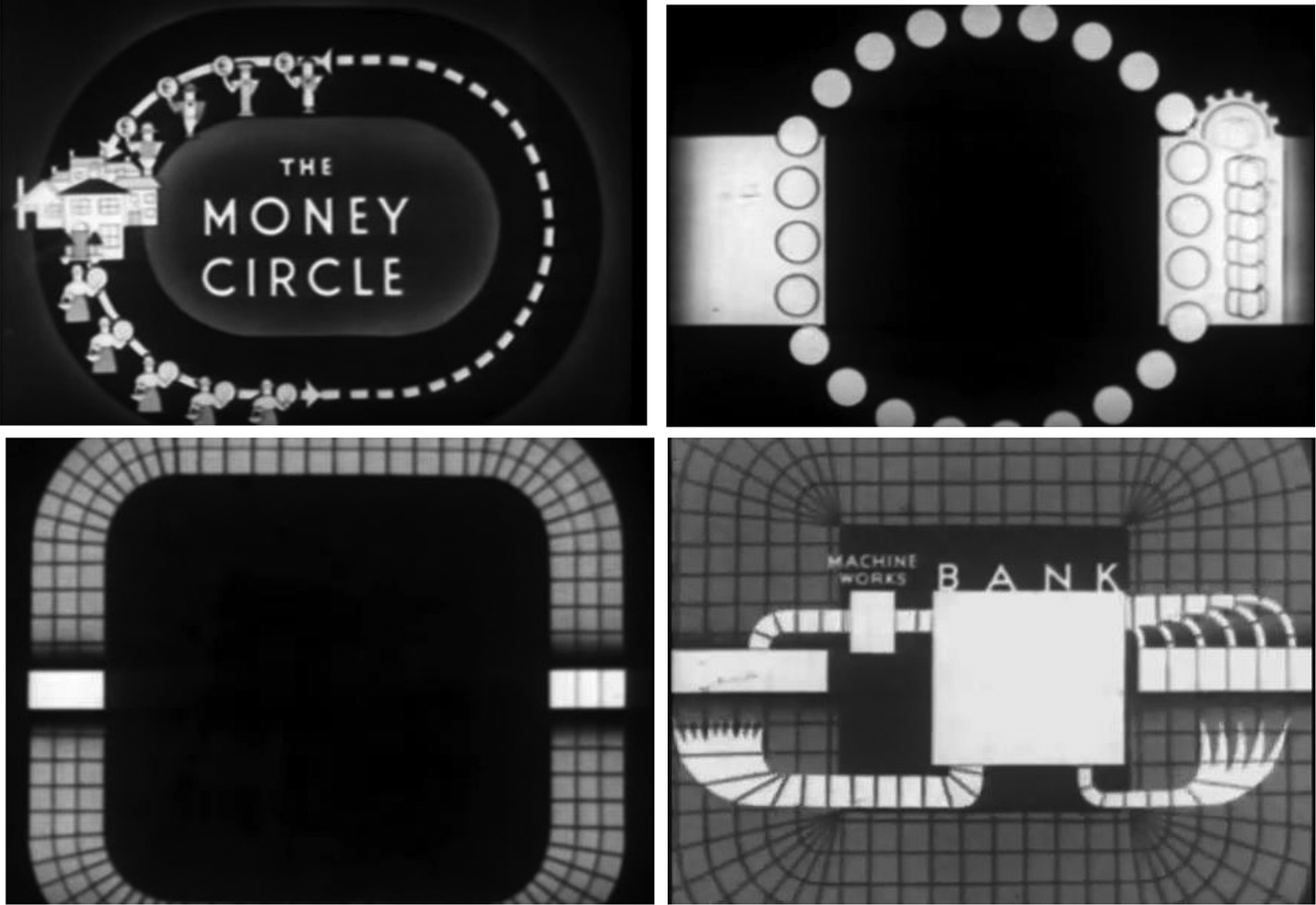

Third, Polanyi was teaching visual fluency in a gradual way (see Figure 4). In Polanyi’s film, as the plot advanced, the visual language gradually leaves behind the common representations and becomes increasingly abstract. Only Polanyi attempted to teach his visual method in this gradual way to help viewers digest the final, abstract representations. None of the other visual methods used this strategy.

Figure 4. Gradual Change in the Representation of the Money Circle

Polanyi’s film was ready to be shown to the public in 1938 after a few private screenings for friends and family. The first public screenings of An Outline of the Working of Money (Reference Polanyi1938a) took place at the London Film School, the Manchester Statistical Society, and the Walter Lippmann Colloquium (1938). Oliver Bell (director of the British Film Institute) and Richard Stanton Lambert (board member of the British Film Institute) gave detailed feedback to Polanyi after the film school screening. Lambert criticized the “slowness” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1938b) of the film and the “repetition” of certain parts but praised its “complicated yet lucid climax” (ibid.). Bell emphasized that those students who would benefit most from this new kind of ”visual notation” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1938c) are those who do not get along very well with verbal or numerical notations (ibid.). He suggested Polanyi focus his efforts on a specific group of students having this trait: adult education students. Acknowledged liberal economists such as Friedrich August von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and Wilhelm Röpke participated in the screening at the Walter Lippmann Colloquium. Most of the professional economists who saw the film apparently did not like it very much. They regarded the film as providing a selective and oversimplified portrayal of complex economic processes. The Evening News called Polanyi’s film the “art of a new Walt Disney” (unknown 1938) and praised the novelty of Polanyi’s experiment. Nature described the film as the first venture to apply the “methods of visual presentation to economic theory" (unknown16 1938). There were, at least, ten press releasesFootnote 7 in the two years after the premiere, but seven were published in one newspaper: The Manchester Guardian (Beira Reference Beira2017). Perhaps this asymmetrical dissemination explains why the first version of the film remained generally unnoticed.

III. DEVELOPING THE SECOND VERSION

Polanyi had the idea in 1939 to make a second film with the title Population and Economic Life, but he instead started to work on a revision of his first film. This revised, second version, titled Unemployment and Money: The Principles Involved (Reference Polanyi1940a), premiered in London in April 1940, and in New York in November of the same year. Several economists, including John Bell Condliffe, Jacob Marschak, Adolph Lowe, and Oskar Morgenstern, participated in the American screening. They did not give detailed feedback but did provide brief remarks. Once again, as professional economists, they complained about making a too simple account. However, the perception of the second version was different from the first in at least two respects. First, press coverage was various. And second, several economics tutors were involved in educational experiments based on the film.

The press coverage addressed many different aspects of Polanyi’s film. One emphasized that it portrays the “functions” of economic organs instead of their “size, weight and shape,” the latter being conventional in contemporary visual regimes (unknown2 1940). Another noted that the film focuses on the “principles” and not the “results” of economic activity (Williams Reference Williams1941, p. 1). This review insightfully suggested that Polanyi embraced a new kind of learning, which was based on “sustained reasoning about facts” and not the accumulation of “encyclopaedic knowledge” (ibid., p. 2). Yet another account praised Polanyi’s method by stating that “instability” (unknown2 1940) and “adaptability,” essential aspects of economic life, cannot be grasped by photographs, static diagrams, and documentary films but can be grasped by this “new mental tool” (ibid.). The film’s potential to counter public confusion and propaganda was also noted.

The Financial Times (unknown14 1940) and To-Day’s Cinema (unknown15 1940) called Unemployment and Money the first film on economics. Other papers indirectly made the same point with column titles such as “Economics by Film” (unknown12 1940) or “Economics on the Film” (unknown13 1940). Some accounts also praised Unemployment and Money as the first instructional film (partly) sponsored by a British university. However, not everybody praised the film. A reviewer for the Documentary News Letter lashed out at the “monotonous geometrical symbols” of abstract diagrams, and missed “concrete … vivid and realistic pictures” (unknown3 1940, p. 6). Polanyi publicly defended his “economic drama” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1937d, p. 15) in the same journal two months later. He argued that “the main documentary approach to economic life represents a technocratic view of production which is essentially collectivist” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1940b, p. 6). He decided not to use this approach in his film because he did not want to develop and disseminate a technocratic view. He wanted to present a commercial view instead, portraying the “grand circle of exchanges” and the “gyrating money belt.” Polanyi drew a parallel between how maps depict the island nature of Britain with a closed curve along its coastline, and how his film represents the monetary circulation by a “rotating belt of definite width and rate of gyration” (ibid.). Both are diagrams making otherwise invisible things visible.

In his ripost, Polanyi compared diagrams and photographs. He contended that diagrams guide reason by explaining, while photographs appeal to the senses and emotion by illustrating. Polanyi perceived his film project more as an explaining than an illustrating experiment, which primarily provides enlightenment and not visual appeal to his lay audience.

The other important difference in reaction to the second version was the educational aspect. Polanyi joined forces with Harold Shearman of the Worker’s Educational Association to organize systematic educational experiments. Shearman coordinated the experiments, collected the feedback, and sent it to Polanyi in large batches. Eventually, a final report was compiled, summarizing the tutors’ experiences with the film. This report, titled “The Film in Economics Classes: A W.E.A. Experiment” (1942), gives an inside view of the testing initiated in November 1941. Nine economics tutors and Polanyi were involved in the experiments, which ended in 1942.

There were important common themes in the tutors’ accounts. First, the audio of the film forced the tutors into silence (unknown4 1942). Some tutors complained that the audio track of the film had limited their freedom to teach what and how they pleased. Some noted that this novel method of teaching made conventional methods like blackboard work unnecessary, regardless of whether the sound or the silent version was used. Interestingly, others argued that the novel method made conventional methods even more necessary than before because tutors needed to explain with their usual tools what was happening on the screen and why. Technical difficulties at times made the life of tutors significantly harder than usual. One of the tutors, H. Dawes, noted that it took three-quarters of an hour for the operator to get a properly focused picture on the screen. Other reports noted a blackout and an improvised screen. Several tutors noted that the film was useful for intermediary students but left beginners confused and advanced students unsatisfied. Others praised the film by noting that it gives “very valuable,” “invaluable,” “extremely useful” aid in portraying the Keynesian exposition of the monetary circulation and the trade cycle.

Finally, tutors were not satisfied with either the represented economic ideas or the way of representation. Some pointed out that Keynesian ideas were controversial among economists, which made them inappropriate for standardized teaching. Others simply rejected Keynesian economics and saw Polanyi’s film as a depiction of (and an attempt to spread) fallacious ideas. Some tutors went into detail about the content of the film. One of them was not pleased by Polanyi’s portrayal of managerial decisions regarding ageing and renewals. According to this tutor, the film also did not adequately represent how monopoly conditions affect corporate policies and how the “volition” of the banking system influenced the trade cycle. Other tutors complained about terminological incompatibilities with contemporary economic discourses, an oversimplified view of investments, and a fallacious idea about why booms come to an end. Polanyi was even advised to develop an additional reel or reels about the banking system, showing how credit issue practices and interest rates of commercial banks affect the economy (ibid.).

By five years after the premiere of the second version, it was clear that the impact of the film was far from meeting Polanyi’s expectations. Shearman, who had become an ally to Polanyi after the initial WEA experiments, summarized his own conclusions and specified two main reasons for the failure. First, economics tutors had not become interested in using visual aids to “any important extent” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1945b, p. 1). They did not have a problem with Polanyi’s film, but they did have a problem with using visual notation. Second, the wartime conditions impeded furnishing British schools with projecting devices and thus indirectly hindered the spread of the film. There is another fragment in the same letter from Shearman that should be mentioned: Shearman told Polanyi that he recently saw some experimental instructional films in the United States, which used a different technique, one that is “more related to the Disney Cartoon” (ibid., p. 2). One cannot avoid recalling here one of the early press releases calling the first version of Polanyi’s film the “art of a new Walt Disney.” One might wonder: How did the “art of a new Walt Disney” (unknown 1938, p. 1) come to be seen as less ’disneyian’ than other artifacts from 1938 to 1945? The answer is suggested in a letter from one of the economics tutors. This tutor argued that after getting “past the novelty of [the] experiment” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1943a, p. 1), most tutors would join him in opposing this kind of standardization in teaching economics. In 1938, the Walt Disney metaphor referred to the pioneering nature of Polanyi’s artful film, which was seen as conquering uninhabited artistic and scholarly realms. However, that changed significantly during seven years. The Polanyi film came to be seen as threatening already inhabited realms. From a novelty, it become a surrogate. Its ’disneyness’ changed to ’undisneyness’ as its newness turned into otherness. The perception of the film shifted from artfully providing visual notation for otherwise invisible social matters to constraining tutors from crafting their own arguments as they pleased. Polanyi was aware of this negative reaction and started to work on other backup plans even before receiving Shearman’s disheartening summary.

IV. FROM FILM TO BOOK

One of these backup plans was to write a popular book on Keynesian economics. In a letter of November 1943, Polanyi mentioned to John Hicks that he was planning to write an economics book for a lay audience (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1943b). He asked Hicks to write an introduction, but Hicks declined the invitation. Hicks told Polanyi that if they were both living in the US, he would definitely join forces with Polanyi. But in the UK the Balogh school was so influential that Polanyi’s proposed book would not find an audience. In Hicks’s view, the Polanyian approach was incompatible with the Balogh school in two important respects. First, Polanyi thought that economic policies can and should aim for full employment. And second, unlike most advocates of the Balogh school, Polanyi did not support “thoroughgoing exchange control” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1943c, p. 1). Whether Hicks was right about the Balogh school or not, his pragmatic reasons for not joining Polanyi shed some light on the perceived political entanglements of articulating new economic ideas in the UK during World War II.

By the next July, Polanyi had written a manuscript of 80,000 words about economic policy (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944a). Jewkes advised him to narrow his topic and to shorten his manuscript, an advice that Polanyi followed. Polanyi continued work, using the title Full Employment in Theory and Practice, and aimed to finish his book by October. He sent the manuscript to Cambridge University Press at the end of October, but he did not have high hopes. He even had some preliminary talks with Karl Mannheim about publishing the book at Routledge after the anticipated Cambridge refusal (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944b). But his worries proved to be unfounded. His book was published by Cambridge University Press under the title Full Employment and Free Trade in 1945.

Polanyi told Shearman that he used the film symbolism for illustrations in the book and made a reference to the film, which he hoped would “reopen the issue of a wider use of the film for economic teaching” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1945c, p. 1). While the book did not become a classic, it was widely read and discussed. Although some earlier accounts have claimed that “very few” reviewed Full Employment and Free Trade (Mirowski Reference Mirowski1998, p. 40), there was press coverage in at least twenty-eight publicationsFootnote 8 in the two years after the first publication. These ranged from short, lay accounts in dailies to detailed expert reviews in journals. Polanyi’s book was thus discussed by both daily columnists and prominent economists like Roy F. Harrod and Thomas Balogh.

There were several common elements in these accounts. Most reviewers noted that Polanyi made considerable progress in realizing his aim to transform Keynesian ideas into a matter of common sense. Nonetheless, they did not agree about the degree of this progress. Some called it an “accurate” and “lucid exposition” (Arndt Reference Arndt1946, p. 567) displaying “clarity and logic” (unknown5 1946, p. 155) with “inevitable reasoning” (ibid., p. 156). Others praised Polanyi’s conversion on the whole but criticized him for using “oversimplified and crude language devices” (Stead Reference Stead1946, p. 204) to amuse his lay audience. Still others scornfully noted that while the little book was undoubtedly “Keynes made easier” (unknown6 1946), it was far from being “Keynes made easy” (ibid.).

Another recurring theme was acknowledging Polanyi’s overt passion for saving liberalism and Western civilization. Reviewers saw him proposing “ultra-liberal principles” (Arndt Reference Arndt1946, p. 567) in an “aggressive form” (ibid.) in which “his every page breathes zeal” (Phelps Brown Reference Phelps Brown1946, p. 110), and championing free price economy against socialistic tendencies (Stead Reference Stead1946, p. 204). They reflected on his “passionate desire for a society in which individual freedom has as full play as possible” (Gilbert Reference Gilbert1946, p. 85) and called him an “enthusiastic member of the Keynesian school” (unknown7 1946, p. 185), stimulating various readers. Having a “laudable purpose” (unknown8 1945) and discussing his topic with “sincerity and zeal” (Sagar Reference Sagar1946), not only did Polanyi prove himself to be an “ardent advocate of Keynes’ ideas” (unknown9 1946) but also a scholar “engaged on a crusade for laisser[sic]-faire economics” (Balogh Reference Balogh1946, p. 252). Accounts claimed that he also did a good job in raising an “acute sense of urgency” (Wilson Reference Wilson1946, p. 880) in others by showing how his economics was relevant to their everyday life and why his story matters.

Contemporary reports were consistent about the main points of Full Employment and Free Trade. Reviewers agreed that Polanyi developed an essentially Keynesian but unorthodox economic framework. They saw the Keynesianness in advocating budget deficit and monetary policy to counter mass unemployment and the non-Keynesianness in the origins of the budget deficit (only from tax remissions) and in the proposed principle of neutrality. For some, the latter meant that the policy of full employment should be completely separated from every other policy (T.M.R. Reference T.1946, p. 471; unknown5 1946, p. 156). For others, it meant that this policy should not involve “materially significant economic or social action” (Arndt Reference Arndt1946, p. 567; Gilbert Reference Gilbert1946, p. 90; Lindblom Reference Lindblom1946, p. 463). For still others, it was a policy against corruption and arbitrariness (unknown5 1946, p. 156; Phelps Brown Reference Phelps Brown1946, p. 110). Full Employment and Free Trade suggested all these meanings. Polanyi argued that malfunction and corruption were inherent to policies based on discretional decisions. Neither the morals nor the knowledge of our leaders could completely be trusted. Fewer discretional decisions meant less opportunity for corruption and failure. The principle of neutrality, Polanyi proposed, would authorize leaders to define the amount of money in circulation but not where money goes, thus reducing undesirable tendencies.

Some reviewers suggested that this neutrality of the Polanyian proposal made the book at the same time too Keynesian for non-Keynesians and not Keynesian enough for Keynesians (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1946, p. 463). And it is hard to argue with this statement. Non-Keynesians were not pleased by the claimed relation between money and employment. Keynesians were not pleased by the taking away of their favorite tools: public works and trade control. A reviewer pointed out that the central argument of the book was actually independent of Keynes (ibid.). Another noted that it was “not simply a rehash” of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (unknown10 1945). But, of course, what counts as Keynesian was also ambiguous. Harrod warned in his review that “planners have [so far] claimed him [Keynes] for their own, while old-fashioned Free-traders have turned a deafer ear” (Harrod Reference Harrod1945). According to Harrod, Polanyi was one of the few free traders listening to Keynesian tunes. Joan Robinson, a hardcore Keynesian, told Polanyi that they differed on one crucial point: she did not think that “’back to free competition’ is a practicable solution” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944c, p. 1). A monetary reformer described the book as the “most lucid statement of our main thesis” (Fountain Reference Fountain1946, p. 5) so far but admitted that the negligence of banks probably makes it harder for fellow reformers to embrace Full Employment and Free Trade. Monetarists, indeed, did not take up the book. And it has only been suggested decades later that Polanyi might have synthesized Keynesian and monetarist economics (Craig Roberts and Van Cott Reference Craig Roberts and Cott1999).

Polanyi was against various kinds of economic planning. Restrictionists, trade unionists, socialists, and Keynesian planners were all advocating economic policies that were incompatible with his neutral Keynesianism. The only planning Polanyi supported was monetary planning. He suggested Parliament should agree on the national income for the country for the next year, and realize the plan by issuing money accordingly (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1948, p. 150). Polanyi rejected the gold standard (ibid., p. 114) and proposed a system of flexible exchange rates instead, which would be supervised by a world bank (ibid., p. 118). He imagined this international financial institution as monitoring the balance of payments between countries and taking care of derived balances that come from national-scale readjustments of employment. The other kind of balances—spontaneous balances that come from changes in production and trade relations—were expected to be left completely to the market. But Polanyi also noted that this world bank would maintain the international monetary circulation and take measures to avoid the depression of national currencies below purchasing power parity, and that it would help depressed areas by giving loans and subsistence allowances (ibid., p. 119).

Some reviewers suggested that there were basic inconsistencies in Polanyi’s proposal. He argued against every kind of planning as contrary to free competition but then developed a new, monetary kind of planning. He noted that national parliaments should be in charge of monetary circulation based on the desired trade-off between employment and money (ibid., p. 150); however, he then proposed a world bank to supervise the global monetary circulation and to help depressed regions if necessary (ibid., p. 118). A strange dialectic of being taken care of and being left alone ran through the entire narrative of the book, whether Polanyi is considering individual economic agents or national economies. Most reviewers who perceived this inconsistency, even those having sympathies towards him, could not unpack this strangeness otherwise than as a contradiction.

One reviewer saw Polanyi joining forces with Hayek, calling Polanyi the “buoyant economist” (unknown11 1946), and Hayek the “warning prophet” (ibid.) of liberal capitalism. Despite this account, Polanyi and Hayek were rarely (Allen Reference Allen1998) seen as brothers-in-arms by contemporaries. The complexity of their partly joined but partly separated endeavors to save liberalism has been treated in the illuminating study by Struan Jacobs and Phil Mullins (Reference Jacobs and Mullins2015). Previous studies about the two were mostly concerned about finding out who should be seen as the reanimator of the concept of spontaneous order. Some scholars argued that Polanyi recoined the concept for modern neoliberal narratives (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1997, Reference Jacobs1999, Reference Jacobs and Leeson2015). Others argued that it was Hayek who did much of the recoining (Caldwell Reference Caldwell2004; Bladel Reference Bladel2005). The liberalism of Hayek and Polanyi has been recently addressed in two doctoral dissertations, one providing a comprehensive account of neoliberalism in the 1930s to 1950s (Beddeleem Reference Beddeleem2017), and the other analyzing how Polanyi perceived his own liberal endeavors in relation to those of the others (Bíró Reference Bíró2017).

Not surprisingly, Polanyi’s most severe beating came from Balogh, who lashed together three new economics booksFootnote 9 and smashed all to tiny shreds in the same brief review. While Polanyi and Harrod were, no doubt, needling him, Balogh accused them with having commitments, which, of course, he also had. Balogh claimed that it is a “pity that his [Polanyi’s] prejudices prevent a logical development of his reasoning” (Balogh Reference Balogh1946, p. 253); he argued that calling Soviet Planning an economic failure was not being “grateful for the heroic sacrifice of the Russian people” (ibid., p. 252). But what has being or not being grateful for something to do with economic facts and logic? Balogh was quick to spot the commitments of others but was blind to his own commitments. Similarly, he gave a thorough bashing to “Mr. Churchill and his deflated myrmidons” (ibid., p. 253) in the part of his review that was dedicated to Harrod’s book but did not acknowledge how his own socialist sympathies might affect his perception of the volume. Balogh complained about how Harrod dismissed certain possible economic measures (long-term planning, security to peasants) as “Schachtian bullying” (ibid.) but did not mention that all these measures Harrod condemned had the stamp of socialism on them. No doubt, pointing out the possibility of having any kind of commitment himself would have made Balogh’s review even more convincing.

V. TOWARDS A THIRD VERSION

Another backup plan was to develop the film further. Polanyi’s initial plan in 1938 was to eventually establish “a library of economic films” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1938d, p. 4) with tailor-made slides and manuals for each. This ambitious plan stayed in the desk drawer after the flop of the first version. After this initial failure, Polanyi focused his efforts on making a new single version of the film and not on making versions tailored for diverse audiences. Shortly after the rollout of the second version, Polanyi realized that the new version also did not meet his expectations and started to work on his economics book, Full Employment and Free Trade. But he still did not give up on his film project in the early 1940s, and in this period promising news arrived from an unlikely place: Orwell’s ministry.

Basil A. Yeaxlee, a well-known figure in British adult education, told Polanyi’s collaborator, Harold Shearman, that the Film Division of the British Ministry of Information (1938 to 1946) might be interested in the film (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1942a). Arthur Koestler helped them contact Arthur Calder-Marshall, who worked at the division (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1942b). Shearman worried that the ministry would transform the film into “propaganda for their policy” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1945d), but Polanyi was not so suspicious about working with the government. He wrote to Jewkes that he would be delighted to help the government to use the current version of his film or to develop a new one about the prevention of general unemployment (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944d, p. 1). Polanyi suggested making a new version based on the first three reels of Unemployment and Money, reducing its size to two reels and adding a new component about governmental intervention. He provocatively suggested the possibility of introducing color (ibid.). However, Polanyi never developed this new version proposed in 1944. The reasons are unknown. Perhaps the ministry indeed wanted to transform his film into a vessel for propaganda and he was unwilling to allow this. Perhaps the ministry did not like Polanyi’s film or did not consider it adequate for popular education. Or, perhaps for more prosaic reasons, the military did not take on this film project: insufficient resources or bureaucratic realignments.

For whatever reasons, Polanyi did not develop his film further, but he turned his attention from economics to philosophy after 1945 (Moodey Reference Moodey2014). This does not mean that he did not show an interest in economic matters anymore but that he rather addressed these issues as specific manifestations of more general social matters. Polanyi’s concepts of spontaneous order (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1951) and tacit knowledge (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1958, Reference Polanyi1966) were used not only to describe economic matters. Polanyi developed these concepts in order to be able to address various social phenomena in diverse settings. Spontaneous order was used to describe the operation of the market mechanism, but it was also used to describe how science evolves and how democracy works. Neither was the sphere of tacit knowledge limited to economic matters. It was framed as an implicit epistemic component of all knowing quite unrelated to the content of knowledge.

VI. CONCLUSION

As an intermediary step between his pursuit of economic statistics and his general philosophical endeavors, Polanyi’s neutral Keynesianism mirrored his still-developing thoughts about how philosophical and ideological entanglements permeate the very fabric of political and economic systems. In “U.S.S.R. Economics” (Reference Polanyi1935a), he showed how Communist ideology affects economic valuation and statistics under a full-fledged dictatorship. Full Employment and Free Trade (Reference Polanyi1945a) and Unemployment and Money (Reference Polanyi1940a) suggest that Polanyi realized how certain traits of economic policies might foster corruption and unfair economic results in contemporary democracies. In “The Growth of Thought in Society” (Reference Polanyi1941), The Logic of Liberty (Reference Polanyi1951), and other later writings, Polanyi claimed to find the commonalities of various social defects residing in diverse social realms ranging from the legal environment through the economic system to the political establishment.

Polanyi was also worried about economics as a discipline. He thought that the mechanical, materialist view of science (including economics) and the critical method “led science to behaviourist and utilitarian exigencies” (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944e, p. 3). Polanyi’s work in economics is thus in tension with Philip Mirowski’s very broad claim that “it was taboo to speculate about mind, and all marched proudly under the banner of behaviorism” (Mirowski Reference Mirowski2002, pp. 6–7) in the 1930s to the 1950s. Clearly, Polanyi’s philosophy of economics is a counternarrative, which deserves its own account (Bíró Reference Bíró2019).

This essay has discussed a specific component of Polanyi’s economic thought, his neutral Keynesianism, which was mirrored in the consecutive versions of his pioneering educational film and his economics book, Full Employment and Free Trade (Reference Polanyi1945a). It showed why Polanyi, an acknowledged physical chemist, turned to social sciences and how his related endeavors were perceived by others inhabiting various social worlds. The essay demonstrated the embeddedness of his economics in the mainstream liberal tradition of his time, but it also addressed its unorthodox elements. Polanyi’s theoretical and representational novelties ranged from the neutrality of his Keynesianism to the distinguishing characteristics of his visual method. Polanyi’s drawing as (Vertesi Reference Vertesi and Coopmans2014) practices were drawing Keynesian economics in a specific way: as an economic theory focusing on the relation between the circulation of money and unemployment. Other conventional aspects of Keynesianism were downplayed or completely missing from the film; e.g., the economic role of the state. It was inherent to how Keynesian economics was drawn to whom it was drawn. Polanyi was drawing it for the general public, for those without advanced training in mathematics. And it was particularly important for Polanyi that these masses see Keynesian economics as an economic theory suggesting to fight unemployment with an increased circulation of money rather than as an economic theory suggesting to fight unemployment with an increased reliance on the state. His initial reason for entering social sciences explains why. The analysis showed that the consecutive versions of the film and his economics book were both part of Polanyi’s mid-life endeavors to counter fascism and communism by conveying liberal economic ideas to the masses in a comprehensible way. Polanyi recognized that questions of economics and democracy were intimately connected, and he was working on economics education for the betterment of democracy. This overarching social aim permeated not only into Polanyi’s verbal but also into his visual representations, suggesting that if historians of economic thought put a stronger emphasis on visuals—even in inquiries not primarily focused on visual representations—the result could be richer and more grounded social histories.