Before the Allied Powers’ historic storming of Normandy in June 1944, they first invaded the island of Sicily to get a foothold in continental Europe. In August 1943, nearly a month after the beginning of the operation to occupy Sicily, General George S. Patton visited an Army hospital where Private Charles Kuhl was hospitalized for shell shock. Referring to the trauma he had experienced, Kuhl said he “just couldn’t take it” anymore. Patton, widely known for his “tough” demeanor, “immediately flared up, cursed the soldier, called him all types of a coward, then slapped him across the face with his gloves.” Holding onto an earlier war’s understanding of shell shock as only really disqualifying if it resulted in physical incapacitation, Patton then “grabbed the soldier by the scruff of his neck and kicked him out of the tent.” General Patton’s “slap heard around the world” created a media firestorm, revealing both Patton and the American public’s limited understanding of mental illness in the 1940s. Many Americans sent “Letters to the Editor” in a variety of national newspapers that conflated cowardice with mental illness and stigmatized both. One mother wrote that she supported Patton’s actions, claiming that he was simply trying to get Kuhl “to man up” because war required real men. Even Kuhl’s family believed that his hot temper provoked Patton enough to warrant the slap, not his psychological distress.Footnote 1

The incident reveals the many ways that 1940s Americans stigmatized mental health issues, despite the prevalence of wartime psychological problems. The “slap heard around the world” highlights the context in which returning veterans from the war would lobby for a landmark piece of legislation intended to address the psychological problems World War II recently exposed. According to historian Jeanne Brand, “World War II turned up some very unpleasant statistical indices of national health—none more startling than those on mental and nervous diseases.” With the extensive influence of veterans, who hoped to disassociate cowardice from mental illness, the United States Congress passed the National Mental Health Act (NMHA) in 1946.Footnote 2

The NMHA continued a long history of legislative efforts to aid veterans and vastly expanded the state’s understanding of what it meant to fully rehabilitate veterans, both physically and psychologically. These efforts began during World War I when the US government passed and amended a landmark piece of legislation—the War Risk Insurance Act. This act guaranteed life insurance to veterans while including provisions for the “rehabilitation and re-education of all disabled soldiers.” By the time the war concluded, the United States faced a significant problem—how to care for the 224,000 physically disabled veterans returning from the front lines. In addition, thousands of other servicemembers suffered from disease, other injuries, and psychological trauma. Learning from the consequences of the Civil War and the extremely high cost of veterans’ pensions, American officials no longer wanted to offer extended pensions that burdened the country’s financial status or permitted disabled veterans to become economic “dependents.” Instead, following World War I, leaders emphasized the need to “rehabilitate” disabled veterans to become both fiscally and physically independent. Americans believed that injured veterans should become fully self-sufficient by actively engaging in the rehabilitation process to overcome their disabilities and reintegrate into civilian life. If they did not put forth the effort, their lack of effort seemingly absolved Americans of their perceived responsibility to care for the returning veteran.Footnote 3

Between World War I and World War II the emphasis on rehabilitation changed from a focus on physical to one on psychological disabilities. Indeed, advocates after World War I focused on the physically disabled veteran and placed less emphasis on the mental rehabilitation of those returning with psychiatric issues. The veteran programs also impelled American citizens through education “to accept disabled soldiers” back into “normal” society. World War II, however, changed the nation’s response to postwar veteran treatment by focusing public attention on the psychological reintegration of returning servicemembers. A new generation of veterans fought to destigmatize mental illness and rehabilitate those who suffered from it at the end of World War II with demonstrable political success. In 1946—less than a year after the war—congressional debates and hearings led to the passage of the NMHA, the first major national legislation on the subject. Veterans yet again took on the mantle of political actors and lobbied for a landmark piece of legislation that, among other things, sought to destigmatize psychological problems by educating the public about mental health.Footnote 4

This article examines post–World War II veteran activism for the NMHA as a critical moment in the nation’s history of mental health care. The passage of this act marked the end of the federal government’s apprehension about addressing mental health policy. Due to Americans’ focus on posttraumatic stress disorder among modern-day veterans in recent years, it is hard to fathom that the government barely intervened in mental health policy before 1946. In fact, historian Gerald Grob writes that state governments originally held responsibility for citizens’ mental health due to a nineteenth-century presidential veto that forbade the federal government from legislating mental health policies. Because of this apprehension, the country’s antiquated mental health system relied on county and state-funded asylums built in the nineteenth century where contemporary psychiatric professionals diagnosed and treated mental illness with little aid from communal and family support systems. With zero to little funding from the federal government, by the mid-twentieth century, these asylums were in shambles. World War II home-front mobilization exposed these shortcomings and demonstrated to the American government that it needed to make changes. Because most psychological and psychiatric professionals were serving in the military, the government required conscientious objectors to serve in the local mental hospitals. These “intelligent, high-caliber attendants witnessed the neglect, over-crowding, often barbarism, in public mental hospitals throughout the country.” Their accounts “jolted” American citizens and officials from inaction to action. Even as the nation experienced “a rising standard of living and general prosperity” during the war, Americans realized that mental health infrastructure was severely lacking.Footnote 5

With a clear victory and permeating “good war” narrative, World War II provided veterans with an expanded opportunity to serve as influential political actors and help mitigate the emotional consequences of war. Moreover, the passage of the NMHA after the war shows that the government embraced mental health care as its responsibility alongside physical care. Although complex forces spurred the act’s passage, the war and disabled veterans allowed politicians to see the importance of such legislation for civilians and servicemembers alike. In a country where millions of servicemembers from World War II “exemplified the best of American grit and spirit” and a place where some advice literature asked family members to bend to veterans’ desires and needs, veterans embraced a new legitimacy to help influence policy making.Footnote 6

Those servicemembers and veterans who testified on behalf of the NMHA continued a tradition of serving as political actors and laid the groundwork for future veterans to petition for better mental health care. Previous generations of veterans had lobbied for federal legislation, perhaps most famously for the post–World War I Bonus. Some scholars argue that the “veteran experience” for those returning home from World War I was largely negative. They returned to a country still coping with the ripple effects of isolationism. The Great War “produced limited public mobilization and little social consensus about the need to fight.” This limited engagement occurred because American involvement in the war was “not a defining national experience,” with no clear legacy as isolationism continued and the League of Nations failed. Outside of the Bonus March in 1932, veterans of World War I engaged in relatively little activism and were not widely accepted as political authorities right after the war. World War II, on the other hand, which mobilized a much greater percentage of all Americans than World War I, produced a veteran population that engaged in widespread political activism. After the deadliest war in world history with over 400,000 Americans killed and many more suffering the physical and mental consequences of war, veterans organized in a concerted effort to pass legislation focused exclusively on mental health, and civilians and policy makers were eager to listen. Former servicemembers who advocated for the NMHA had served in various wars, from the Spanish-American War and World War I to World War II; some held positions of political power, such as Director of the Selective Service Major General Lewis B. Hershey. Others had returned from World War II and understood that other servicemembers like them needed help. Many worked behind the scenes through veterans’ organizations, such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion. Others who testified in the congressional hearings became leading psychiatrists in postwar America. These veterans created the steppingstones for future veteran advocacy groups to lobby for even more health care benefits. The clearest legacy of these actions is the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, which played a significant role in getting posttraumatic stress disorder confirmed as an official mental illness after the American War in Vietnam. Most recently, servicemembers of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have similarly emphasized the need for expanded mental health care.Footnote 7

The history of the NMHA reveals a rare occasion where veterans mobilized for legislation that benefitted not only themselves but also the entire nation. Although each witness in the congressional hearings had a uniquely personal and professional motivation, a deeper examination of the veterans’ statements during the proceedings reveals three similar motives: to educate the general public about mental illnesses, expand the number of health care professionals for better psychiatric care, and, more importantly, to destigmatize mental health problems. For instance, some veterans hoped that the legislation would heighten public awareness and reduce the stigmatization of mental illness that they faced, much like legislation had done for physical disabilities after the First World War. Veterans with medical experience pressed for increased research funding, which, in turn, would lead to new methods, treatments, and, most importantly, forms of prevention that doctors could use in both military and civilian contexts.Footnote 8

Historians have shown how veteran mobilization for a singular cause, even when the veterans often disagreed with each other, was essential to persuade the government to pass landmark pieces of legislation, such as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944. Scholars have examined the history of mental health care, disability movements as a result of war, veterans as political actors, and servicemembers and their mental health. Although some historians have exclusively examined the NMHA and its role in validating and expanding the psychiatric and psychological professions, none has focused specifically on individual veterans and their organizations’ efforts to gain access to psychological rehabilitation through the act. This article brings these fields together by examining veterans’ specific motivations and activism to pass the NMHA, which was, at the time, the government’s most significant intervention in mental health policy.Footnote 9

In pushing successfully for the act, veterans not only helped the nation revolutionize its approach to mental illness but also prepared the way for future mental health advocates to officially recognize and destigmatize psychological disorders in the United States. In a way, veterans’ mobilization for mental health after World War II is a sequel to the movements after World War I that pushed for physical rehabilitation and reintegration. Even though the country lacked the infrastructure to provide immediate rehabilitative services for physical disabilities in the early twentieth century, the War Risk Insurance Act provided the necessary resources to create the veteran’s health care system. To be sure, veterans after the First World War sought aid for their mental health, but their pleas did not result in significant federal legislation. During and after World War II, however, when an astounding number of servicemembers received psychiatric disqualifications and discharges and many more returned home suffering from the emotional scars of war, veterans realized that they needed access to mental health care. The NMHA culminated from this movement, and it provided the resources to develop the necessary infrastructure for the research, treatment, and prevention of psychological problems for not only veterans but also every American. Therefore, the NMHA had enduring consequences because it enlarged the symbiotic relationship between the state and servicemember and helped create a more holistic understanding of health care.Footnote 10

The National Mental Health Act

During World War II, the military rejected 1,767,000 men who failed preinduction psychiatric screenings, and between December 1941 and December 1945, the US Army discharged 980,000 men due to disability; 419,500 of them were psychiatric casualties (approximately 43 percent of all disability discharges). These numbers highlighted the prevalence of mental illness among Americans, and the country needed to take action to care for the servicemembers coming home the war. Robert H. Felix, a Coast Guard psychiatrist who later became the chief of the Bureau of Mental Hygiene, witnessed firsthand the pervasiveness of mental illness in the military. In early 1945, Felix solicited the help of Mary E. Switzer, a social reformer, and J. Percy Priest, a Democratic congressman from Tennessee. Together, Felix, Switzer, and Priest drafted H.R. 2550: The National Neuropsychiatric Institute Act, which Priest introduced in the House of Representatives in March 1945. Claude Pepper, a Democratic senator from Florida, introduced the same act, S. 1160, in the US Senate.Footnote 11

The legislative process lasted over a year as congresspersons debated the legislation’s several measures that intended to overhaul mental health care in the United States. On September 18th, 19th, and 21st 1945, the House of Representatives heard twenty-one in-person witnesses, eight of whom were veterans or their representatives. On March 6th, 7th, and 8th, 1946, a total of twenty-six in-person witnesses, thirteen of whom were veterans, testified before the Senate. Every witness, regardless of civilian or military status, hoped each American citizen would benefit from the legislation’s purposes: “to provide for, foster, and aid in coordinating research relating to neuropsychiatric disorders; to provide for more effective methods of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of such disorders; to establish the National Neuropsychiatric Institutes.” Of the act’s several provisions, the most far-reaching was the creation of the National Neuropsychiatric Institute (later known as the National Institute for Mental Health) because it facilitated government-funded research concerning mental health. Congressional sponsors hoped the research would lead to discoveries concerning etiologies, prevention methods, and cures for mental illnesses. The legislation also called for the creation of the National Advisory Mental Health Council, which, with the US Surgeon General’s approval, would publish research and conclusions to aid federal and state-level organizations. Furthermore, by dispersing research and empirical findings to the public, the act promoted the widespread dissemination of knowledge about mental health. Recognizing that a lack of knowledge led to stigmatization, the bill’s authors reasoned that an educated public would more likely sympathize with those suffering from psychological problems.Footnote 12

According to Senator Pepper, everyone at the Senate hearings had heard of someone suffering from some mental ailment. The return of veterans after the war augmented this problem. Indeed, he argued, “the enormous pressures of the times, the catastrophic world war which ended in victory a few months ago, and the difficult period of reorientation and reconstruction, in which we have as yet achieved no victory, have resulted in an alarming increase in the incidence of mental disease … among our people.” Therefore, Pepper believed Congress needed to pass the legislation quickly, especially with the government’s newly expanded “scope and nature of its authority” after the war.Footnote 13

The National Mental Health Act intended to benefit millions of citizens, psychological and psychiatric professionals, and returning veterans. Within days of the Senate hearings in 1946, the House of Representatives dropped H.R. 2550 and introduced H.R. 4512—The National Mental Health Act. Although this act’s provisions essentially remained the same, there were some differences, including the name. During the hearings, some doctors explained that they did not like using the term “neuropsychiatric.” Instead, they preferred to use “mental health” because they wanted to focus on mental disorders (problems with personality and emotional traits) in addition to neurological sicknesses (ailments that affected the brain and nervous system). H.R. 4512 also amended The Public Health Service Act of 1944, which meant that the proposed institute for mental health would become part of the National Institutes of Health, thereby granting it as much meaning as the National Cancer Institute. Ultimately, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 4512 on March 15, 1946, with seventy-four votes in the affirmative and ten votes rejecting the bill. The Senate then passed the bill in June 1946, and President Harry S. Truman signed it into law on July 3, 1946. As a law, the NMHA offered resources to research the prevention, treatment, and curing of mental illnesses, and it contained similar provisions of the earlier bills, including creating the National Advisory Mental Health Council. Furthermore, the law earmarked thirty million dollars to the council to educate, train, and recruit professionals at the state and local levels. Among other things, including the establishment of national health conferences, the law appropriated 7.5 million dollars to construct the National Institute of Mental Health.Footnote 14

The act’s expansion of federal power over mental health care was not without fault or controversy, however. The legislation marked a large step in federal government intervention, but it did not provide state legislatures with enough funding to meet the demand for mental health services. This shortcoming, therefore, exposed the federal government as unable “to cope with the nation’s total treatment problems in mental illness.” Despite this unsatisfactory funding, some legislators, like John W. Gwynne (R-Iowa), still asserted that the federal government encroached on states’ rights. One congressman, Clarence J. Brown (R-Ohio), rebutted these arguments by showing that many state-level organizations supported the bill. Other congresspersons concerned themselves with the financial aspects. During the New Deal era, the government greatly extended its reach with federal policies, taking on an expanded role in the social welfare of the nation. With the unsurpassed economic growth during and immediately after World War II, Senator Robert Taft claimed that numerous bills requesting financial support sat on legislators’ desks in Washington. Taft feared that the constant funding of projects would “dry up all the money.” Yet, the law itself constituted a milestone in the history of American mental health policy, and the congressional hearings that led to its passage conclusively demonstrate the importance of the unifying strategies that veterans and their organizations used to advocate for mental health.Footnote 15

Veterans’ Organizations and Robert Nystrom

The hearings included testimony by dozens of people from different professions, thereby reflecting the growing importance of mental health. These included Dr. Thomas Parran, the US Surgeon General, and representatives from different mental health-related professional organizations and agencies, including the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association. Some professionals, such as President and Scientific Director of the Research Council on Problems of Alcohol Dr. A. J. Carlson, hoped that the act would uncover the root of substance abuse and provide better ways to treat and prevent drug addiction. Congress also heard the testimony of numerous experts from state-level organizations such as Frances Hartshorne, the executive secretary of the Connecticut Society for Mental Hygiene, who hoped the act would facilitate public education and specifically provide resources for individual states to develop mental health societies to better address local needs. These testimonies played vital roles in convincing members of Congress of the bill’s importance and were instrumental to its passage as they revealed the federal and state governments’ ability to work with one another.Footnote 16

In addition to these witnesses, veterans’ voices and words illustrated the prestige the military enjoyed in the immediate aftermath of World War II. When veterans spoke, Americans tended to listen. As historian James Sparrow writes, “the veteran became a cultural figure who represented the coming postwar order, with all its uncertainties as well as promise.” During this period, civilians and politicians were willing to go the extra mile to support veterans—they remembered the lack of support given to Great War vets, and they did not want another “Bonus March.” The recent passage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 demonstrated this shift by showing public engagement over veterans’ affairs and what the country owed them for their service.Footnote 17

As it happened, much of the testimony of veterans during the hearings did not come from ordinary servicemembers who had served on the front lines during the war. Instead, most testimonies came from representatives of veterans’ organizations, psychological and psychiatric professionals who had served in the military, and other veterans who, at the time, held prominent leadership roles in governmental organizations such as the War Department and Selective Service Agency. Despite their varying backgrounds, these veterans constructed arguments that often intersected with and supported one another.Footnote 18

The two most prominent veterans’ organizations, the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), fought ensure that veterans were entitled to acceptable benefits and played a significant role in the hearings. As scholar Olivier Burtin argues, veterans’ organizations, especially the Legion, “stood at the peak of its power in the postwar period.” Nearly every locale in America housed a Legion Post. With this extensive representation, organizations “could therefore exert direct influence over most of the nation’s representatives in Congress.”Footnote 19

A supporter of physical rehabilitation after World War I, the American Legion focused its advocacy efforts for the NMHA on the new movement for veterans’ mental health, especially concerning public education. In the post–World War II era, the Legion represented nearly three million Americans. The national commander of the legion, Hanford MacNider, declared that “the first duty of The American Legion is to see that those men who came back from their service, blinded, maimed, broken in health and spirit, who must live through the war forever in their homes through the country, get a square deal from the Government they fought for.” Historian Jessica Adler argues that the Legion often advocated for disabled veterans because doing so offered it a public stage and “political legitimacy.” Testifying and playing an active role in the passage of the NMHA provided the perfect opportunity for the veterans’ organizations to unite to fulfill their purposes by representing a collective voice of physically and psychologically disabled veterans.Footnote 20

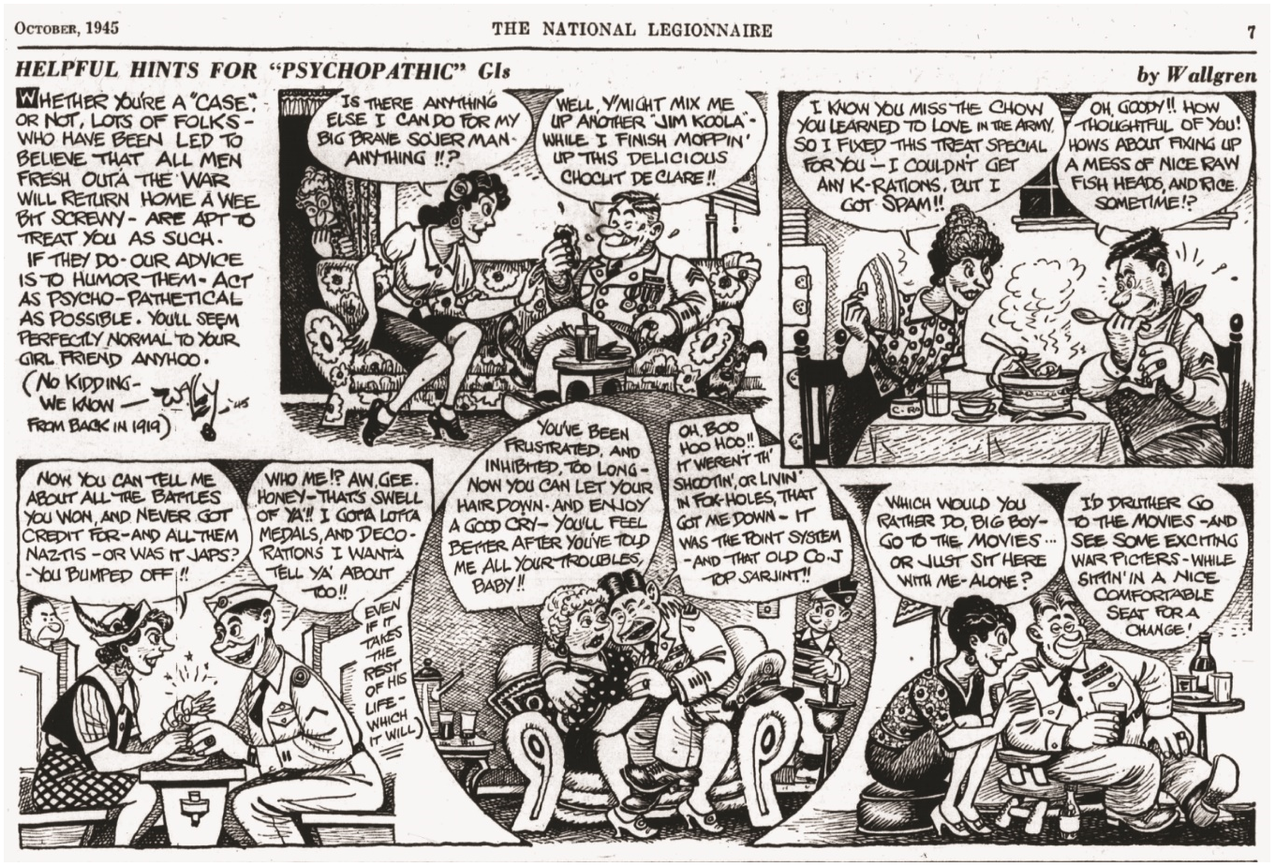

Through its publications, the American Legion demonstrated its desire to aid the mentally ill soldier, even if its “aid” sometimes consisted of joking about mental illness. The October 1945 edition of The National Legionnaire included a cartoon titled “Helpful Hints for ‘Psychopathic’ GIs” (Figure 1). Civilians, it warned, “have been led to believe that all men fresh outa the war will return home a wee bit screwy.” This cartoon jokingly states that if families did indeed treat the veteran as if he was “screwy,” the former servicemember needs “to humor them” and “act as psycho-pathetical as possible.” If the returned soldier followed these instructions, he would “seem perfectly normal to [his] girlfriend anyhoo.” The cartoon asserts that because of a lack of mental health education, the public was unequipped to understand veterans’ mental health needs.Footnote 21

Figure 1. “Helpful Hints for ‘Psychopathic’ GIs.” “Reprinted with permission of The American Legion Magazine, October, 1945. www.legion.org.”

In another sketch, a veteran and his wife are sitting down for dinner. Contrary to advice literature of the period that beseeched women to “not encourage [the veteran] to go on reliving again and again the horrors of it all,”Footnote 22 the wife implores the veteran—still in uniform—to tell her about his combat experience. The wife reveals her ignorance when she asks about “all them Nazis—or was it Japs?—[he] bumped off.” The woman did not know in which theater of operations her husband fought. Nevertheless, with a “psycho-pathetical” smile, the veteran takes his wife’s hand and squeezes it exceptionally tightly, then responds enthusiastically about the many decorations he received. The most revealing part of this cartoon asserts that the man will gladly tell his wife of his experience, but it will take “the rest of his life.” Indeed, the trauma and mental distress that the serviceman experienced affected him for the remainder of his life.Footnote 23 Insensitive by today’s standards, such cartoons illustrated how legionnaires perceived psychological disorders. Moreover, the cartoon casts civilians as ignorant of war and its effects while conveying the idea that veterans were the authorities on mental illnesses because they were the ones who experienced it.

During the September 1945 hearings before the House of Representatives, Dr. Albert Baggs, a medical consultant who testified on behalf of the American Legion, criticized the government for failing to address mental health among servicemembers. He argued that politicians “did not learn anything from the preceding war.” Baggs would later declare that “the medical profession … knows very little about psychiatry, unfortunately. The general population naturally knows less.” Baggs noted that the military discharged approximately thirteen million soldiers for medical and nonmedical causes and that this number, in addition to the number of family members affected by the mentally ill veteran, totaled twenty or thirty million of the approximate population of 140 million people. Thus, Baggs emphasized that veterans’ psychological issues had effects that were beyond those on just veterans themselves. Overall, his testimony reveals two different reasons for the Legion’s desire to educate the public. First, with an unprecedented number of returning soldiers, families needed to know how to help and comfort the veteran at home. Second, a concerted educational campaign would not only create a sense of empathy but also emphasize that mental illness was more common than many people initially thought. This prevalence and education, in turn, could remove some sense of the stigma associated with these psychological issues.Footnote 24

Although the VFW played a lesser role in the NMHA’s hearings, the organization perceived the act as a method to improve preventative care, which, in turn, would relieve the health care burdens on the Veteran’s Administration and military. The organization did not participate in the House hearings of September 1945, but it sent representative John C. Williamson to stand before the Senate subcommittee in March 1946. Williamson relied on statistics to provide evidence of the need for the NMHA. By December 31, 1945, 73,969 World War II veterans had been hospitalized due to psychiatric illnesses. According to Williamson, this number greatly troubled VFW leaders, “whose primary concern is the psychiatric rehabilitation … of our wartime veterans.” Williamson then lobbied for the NMHA to ensure that veterans had efficient preventative and treatment methods. He declared that he did not minimize the significance of the treatment and diagnosis stages but affirmed the importance of the act’s role in uncovering “preventative measures.” Williamson argued that the government would help service members avoid psychiatric clinics and veterans’ hospitals by first preventing mental disorders. Yet, for the NMHA to be a solution to prevent psychiatric problems before they turned into significant societal problems, VFW leaders insisted that more doctors were necessary for the research. The country, at this point, did not have enough medical professionals to begin a deep investigation of mental health—a concern that military psychiatric professionals also addressed.Footnote 25

The VFW’s spokesperson diplomatically but firmly critiqued the government’s handling of mental health issues. Unhappy with the dearth of psychiatric clinics and services across the nation, the veterans’ organization argued that current resources were “altogether inadequate to meet the needs of returning veterans.” Williamson argued that the NMHA needed to ensure the expansion of clinics so that suffering soldiers could receive prompt treatment and access “preventative measure[s] to guard against the aggravation of disorders.” Therefore, he emphasized that the National Neuropsychiatric Institute—later known as the National Institute of Mental Health—should play a crucial role in researching effective preventative and rehabilitation methods while also expanding the number of psychiatrists countrywide. Williamson understood that these doctors’ training would take years. An institute would be critical in the interim because research could start as soon as construction was finished. Overall, while the American Legion’s and VFW’s goals for the NMHA were different, they were also complementary. The legion’s representatives focused on public education about psychological problems, whereas VFW’s delegate testified that prevention and rehabilitation issues were equally important.Footnote 26

One unaffiliated veteran, Robert Nystrom, a Naval aviator who suffered from “manic-depressive psychosis,” also lobbied for the NMHA so that medical officials could research and discover better treatments for mental illnesses. Nystrom had spent eighteen weeks in a hospital due to his illness, where he experienced two types of treatments, one of which he excoriated. Calling this form of treatment “loafer’s delight,” Nystrom recounted that doctors told him to rest and give himself time because “time heals all things.” On the contrary, Nystrom insisted that this method made him feel as if he recovered only to relapse into a depressive episode a week later. He felt that he was “loafing” around—being lazy and not actively participating in treatment. He argued in front of the congressional subcommittee that this treatment would not help those who suffered. Instead, Nystrom testified that psychotherapy—therapy focused on changing emotions and behaviors—was the best treatment for the psychologically distressed and had allowed him to recuperate. Historian Jeanne Brand writes that Captain Robert Nystrom’s testimony in the March 1946 hearings “carried no self-pity, but an unquestionable sincerity of interest in the need for active treatment programs for the mentally ill. His statement moved his audience deeply.” Nystrom’s firsthand experience as a mentally ill veteran fit the narrative of the time—veterans needed to be active participants in their rehabilitation so they could become active participants in postwar society.Footnote 27

Like other veteran advocates, especially those with medical expertise, Nystrom lobbied for the NMHA so that servicemembers would have greater access to mental rehabilitation, a goal that required a greater number of psychologists and psychiatrists. His hospital experience revealed an insufficient number of psychological professionals in the military and the hospitals around the country. “In regard to medical judgment,” he argued, “the medical branches of our armed forces were caught mostly unprepared for the gigantic neuropsychiatric problem directly attributable to the war.” The lack of professionals and the inability to create a better regimen went hand in hand, and Nystrom hoped that the NMHA would provide the resources to solve this problem. Not only would there be more readily available doctors trained in the psychiatric disciplines; his “associated veterans” and civilians would also benefit from modern rehabilitation techniques.Footnote 28

Military Psychiatric Professionals

Nystrom’s desire for the NMHA mirrored that of the psychologists and psychiatrists, many of whom were veterans and still active duty, who argued for the necessity of more psychiatrists and better research. These medical officials relied on their professional experiences during wartime when they lobbied for the act. After treating many mentally ill veterans and seeing the damage that psychological stress caused, these professionals hoped to educate the public, reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness, and expand the number of clinics, doctors, and the amount of research being conducted. The number of psychologists and psychiatrists who testified in the hearings shows how important this act was to these doctors. During World War II, psychiatric professionals had fought to stay relevant and secure an established position in the American medical establishment. For them, the NMHA would prove that psychiatry finally received validation and authority in the medical sciences.Footnote 29

In the September 1945 House hearings, Captain Francis Braceland, the chief of the Neuropsychiatry Branch in the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, echoed the American Legion’s argument and explained that only education would reduce society’s stigmatization of mental health. By educating general practitioners and the public, the act would allow veterans to avoid any unnecessary “unhappiness” that occurred when society rejected the mentally ill veteran by not allowing him to reintegrate into civilian life or by denying him a job. Ensuring that Americans, especially veterans, did not become “economic burdens,” reflected the guiding principle of legislation for physical rehabilitation after World War I. Braceland now applied this idea to the mentally ill because “the huge cost of forcing a high percentage of these persons to be economic invalids is not only wastefully extravagant but detrimental to the national morale.” He further asserted that the public needed to learn about mental disabilities to understand that suffering veterans were not hindrances; society should not punish them for their ailments. He declared that “the punitive attitude which characterizes most persons’ intolerance of the emotionally disturbed is as anachronistic in our day and time as it is to cry at a leper ‘unclean.’” Such arguments deflected any contentions that mental health was not a federal concern by making the case that it affected the nation’s economic vitality.Footnote 30

Braceland also testified at the Senate hearings of 1946, where he argued that doctors often lacked sufficient training because the government had not dedicated enough resources to research. Coming out of the war as victors, post–World War II Americans distinguished themselves from previous generations with an emphasis on scientific study and research in order to maintain the nation’s “superpower” status. Braceland reminded the government of its role in fully funding and supporting the militarily successful Manhattan Project. The war created new avenues for research that benefitted science, and it could also advance medicine for the national welfare. In this vein, Braceland testified that government-funded research on psychiatric problems could provide many scientific breakthroughs. Increased funding would produce great strides in psychiatry, just as it had with the development of the atomic bomb.Footnote 31

Major Douglas D. Bond, a psychiatrist in the Army Air Forces during World War II, also lobbied for the NMHA with the goal of promoting mental health and discouraging stigmatization. Like Braceland, Bond pushed for public education about mental disorders as he asserted “that further education, both of the public and medical men, is imperative at this time.” Bond’s motivations, however, differed slightly from Braceland’s in that Bond emphasized the practicality of the legislation for military personnel matters. Acutely aware of many cases of psychological breakdown among airmen, he wanted military officials to have a better grasp on these issues because “many problems [had] arisen … on compensation and how psychiatric disorders should be handled upon discharge from the services.”Footnote 32 Psychological trauma posed particular problems in the Army Air Forces, where commanders disagreed sharply over what symptoms were significant enough to warrant medical discharge. This confusion led to various types of discharges. If doctors convinced commanders that a man suffered from an ailment known as flying fatigue, he could potentially receive medical discharge and all associated GI Bill benefits, including health care. However, if commanders remained unconvinced of the legitimacy of a man’s mental illness, some officials claimed the flyer was a coward who had a “Lack of Moral Fiber.” Such accusations possibly resulted in either a Dishonorable or Other than Honorable Discharge, both of which disqualified the flyer from veteran benefits. A psychiatrist and veteran who had served on the front lines in the war, Bond thus joined the American Legion, the VFW, and Capt. Braceland in becoming a political actor, lobbying for the NMHA with hopes that it would educate society and provide for more precise definitions of psychological problems among veterans. Although each of their motivations was unique, veterans and their organizations fought for common goals and rationales for this landmark legislation.Footnote 33

Veterans in Prominent Governmental Roles

Despite the compelling cases veterans and their organizations made in favor of the NMHA, advocates faced resistance from some legislators in both congressional hearings and the congressional debates. As representatives of the people, certain congressmen displayed an ignorance that mirrored the public’s lack of understanding of mental health issues because there was not one clear definition during this period, even among medical professionals. The testimony of Colonel Samuel Challman in the September 1945 House hearing illustrates the uphill nature of the battle that the act’s proponents were sometimes forced to fight. Like Douglas Bond, Challman was a psychiatrist in World War II, serving three years in the Pacific Theater of Operations where he treated psychiatric casualties. At the time of his testimony in September 1945, he was the deputy director of Neuropsychiatry in the US Surgeon General’s office.

During Challman’s testimony, Alfred Bulwinkle (D-North Carolina) questioned him about soldiers who went absent without leave (AWOL), even implying that something had to be wrong with these men psychologically. He asked if Challman had examined any of the court-martial cases concerning these men to figure out what affected them. Bulwinkle’s remarks reflect the era’s conception of mental illness as a weakness—as if a suffering person was not masculine enough to fulfil his martial duties. By suggesting that those who were court-martialed for going AWOL were mentally ill, Bulwinkle perpetuated stigmatization by linking criminality, noncompliance, and mental illness.Footnote 34

Challman acknowledged Bulwinkle’s question and confirmed that psychological problems had indeed been factors in some AWOL cases but not all. He insisted that “frequently the disability is not such as to relieve him of the responsibility; he still has to take the consequences of his act, even though the psychiatric disability accounted in part for his behavior.” Thus, he argued that mental distress did not always cause a servicemember to commit a crime punishable by court-martial. Challman wanted Bulwinkle and the American people to know that mental health problems did not always cause soldiers to go AWOL or commit other grievous acts. Challman hoped that better education would sever the perceived connection between criminality and mental illness.Footnote 35

Although other witnesses made lengthy statements without interruptions or questions, many committee members interrupted Challman’s testimony with questions that demonstrated their limited understanding of mental illness at this time. One asked: “Did you have any of these neuropsychiatric and psychiatric cases among officers?” and another asked “Have you studied officers who have developed the Napoleonic complex, who want everybody else to do exactly what they tell them?” The queries seemingly raise questions as to whether officers were equally subjected to the same type of mental illnesses as enlisted men. Another member seemed to doubt the legitimacy of diagnoses when he challenged, “Of course, psychiatric specialists test men before they are inducted into the Army; is that right?” Challman spent most of his time answering these queries. Nevertheless, his statement’s main points concerned veteran rehabilitation, reintegration into civilian society, and the fact that psychological problems caused many casualties, which ultimately weakened the US military workforce.Footnote 36

If historians have largely overlooked the role of veterans like Braceland, Bond, and Challman in the NMHA hearings, one veteran who testified has received considerable attention—Major General Lewis B. Hershey. As the director of the National Selective Service System, it fell to Hershey to present most of the statistics concerning neuropsychiatric disqualifications and rejections. His professional background influenced his motivations for testifying. Having witnessed the military reject more than 1.7 million men due to psychiatric causes, he supported the NMHA as a way to strengthen the US military. These rejections had caused the Selective Service a whole subset of problems, such as communal questions as to why some men who, while seemingly qualified for service, were rejected; one important solution to these questions was “to have the public understand the reason for the rejection of those not acceptable.”Footnote 37

Hershey understood that mental illness greatly affected the military because many draftees looked physically healthy and prepared for military service, yet they were not qualified due to psychiatric causes. These men received a “4F” rejection—a rejection reserved for people with psychoneurotic disorders. These rejections obviously reduced the number of people who could serve, they also stigmatized men who were rejected for mental illness. He declared,

it is just as bad for the fellow that happens to have these abnormalities, if we want to call them that, and one of the most difficult things in war … is to try to explain to the rest of the people why you do not require military service of an individual, who, for everything they can see, looks perfectly able to carry out his military responsibility. If a man has got a leg off, he is no morale problem, but if he has one side of the internal arrangements of his head gone, you cannot see it.Footnote 38

In other words, Hershey expressed concern not just for the mentally ill soldier or the mentally ill veteran but for the man whose psychological health kept him out of the service—a man who was misunderstood and stigmatized and thus a perceived detriment to the national morale. The 4F rejection was an instant stain on a person’s record, as it often shamed and embarrassed the rejected man. Employers even avoided employing men with the 4F rejection.Footnote 39

Hershey lobbied for the NMHA because there was a “lack of knowledge in this field that prevented proper classification of men who were in the service.” He believed that the medical field’s misunderstanding of psychological disorders led the Selective Service to reject some men who should have been qualified and to accept some draftees who should not have passed the screening. Better knowledge about mental illness would have led to better psychiatric screenings that disqualified those with more severe cases while allowing draftees to join if their symptoms were milder. For him, the act would have made the preinduction screenings more efficient, which was important because “in wars, in order to win, we must use every available man.” Therefore, he believed that the NMHA, with all of its provisions, provided for better research and a more educated public that, in turn, would create better screening processes that would bolster the US military, especially during this period leading up to the Cold War.Footnote 40

Hershey drew on his World War II experiences but also testified that mental health was an ongoing problem for the nation, both in the military and civilian society. Like other military men testifying in the hearings, Hershey understood the need for a more comprehensive approach to veterans’—and other Americans’—mental health. A line of questioning by J. Percy Priest, the sponsor of H.R. 2550, in the September 1945 House hearing demonstrates how important Hershey thought the act was for both the military and the country. “One of the two or three things that I feel is most vital for the future,” Hershey testified, is that “this [mental illness] ranks with one or two or three of what I think the most pressing problems the country is faced with.” Hershey urged federal intervention in both military and civilian mental health. He hoped that the NMHA would facilitate public knowledge of mental illness for the purpose of destigmatization. Hershey underscored the social costs of mental illness for servicemembers and civilians alike, and his effort to destigmatize psychological problems offers another example of veterans from various backgrounds using strategic arguments to convince Congress of the bill’s importance.Footnote 41

Conclusion

After the “slaps heard around the world,” Dwight D. Eisenhower opened an investigation and ordered George Patton to apologize to the victims and medical personnel who witnessed the events. While speaking with the medical personnel, Patton claimed to believe that shell shock was a true, “most tragic,” illness. He further explained that he only shamed the victims “to get them to snap out of it”—or in other words, he slapped the soldiers thinking he could treat shell shock with stigmatization. Such an assertion highlights World War II-era America’s lack of understanding of psychological problems. Veteran activism for the NMHA intended to solve this problem by educating the public and discovering proper treatments to help servicemembers and destigmatize their mental health problems.Footnote 42

When veterans have served as political actors lobbying for benefits, the “critical ingredient” for success has been their “robust engagement in the political process.” Veterans stood a higher chance of success when they and their organizations united in a singular cause. Although not the only people who helped pass the NMHA, veterans during the post–World War II era followed this formula by engaging in politics and formulating strategic arguments. Their efforts, along with all those who testified, proved successful with the passage of the National Mental Health Act of 1946. In fact, some of the assertions that politicians used in the debates reflected the motives of the veterans and other witnesses during the congressional hearings. For one example, Congressman Walter Judd (R-Minnesota) stated that “one of the greatest tragedies of all time” is the fact “that among most peoples on this earth to have a mental disease has generally been considered a disgrace and a reproach, something evil and reprehensible, both to the individual himself and to his family.” Indeed, he understood that people considered mental illness an evil disease—a curse to the sufferer and his family. Congressman Judd “heartily” supported this bill because the NMHA allowed for “more extensive and thorough research … and wider dissemination of the results.” Judd acknowledged that this wider distribution of research would educate the country, but more importantly, he explicitly hoped that this better knowledge would “help the nonafflicted to realize that an abnormality of the mind or emotions is not a stigma but is just a disease as is an infection of a finger or a broken leg.”Footnote 43

While Judd’s assertions echoed those of the veterans and other witnesses, he specifically stated how important this bill was for servicemembers returning from the war. In fact, he declared that “the most terribly tragic figures” that needed this legislation were not those who suffered physical wounds during the war; instead, it was for those “with their spirits broken.” Judd maintained that this legislation was necessary for veterans because they needed the psychiatric studies to facilitate their transition to productive and independent citizens of the United States. Just as physical rehabilitation helped World War I veterans reintegrate as independent individuals, mental rehabilitation would allow the World War II servicemembers and others to reenter civilian life without being economic burdens.Footnote 44

Until the post–World War II era, the federal government eschewed most matters dealing with psychological sicknesses, but those who testified in support of the NMHA helped convince the government of its role in the social welfare and mental health of its citizens. They used the “wartime state’s” expanded authority and its focus on social welfare to bring much needed attention to the emotional well-being of the nation. The act also ushered in a new era of government recognition that “a community is only as strong as the health and economic welfare of its weaker members.” Although the war and military necessity shaped the contents of the Act, the nation also rallied to ensure that the law aided returning servicemembers with their successful reintegration into society after the deadliest war in human history. The NMHA became a tool to facilitate this reentry by helping Americans and doctors better understand psychological health and the national consequences that would occur if the country continued to ignore it.Footnote 45

These political actors not only influenced the passage of this significant piece of legislation, but because a large number of the veterans who testified were psychiatrists, they also helped legitimize psychology and psychiatry as respected medical sciences. Their testimonies and the NMHA transformed these fields, especially psychiatry, from “a profession primarily caring for the chronically insane in isolated institutions” to “a profession caring for everyone.” Thus, veteran advocates paved the way for future political actors to lobby for mental health “for everyone.” Veterans and civilians alike continue to benefit from the act’s most enduring achievement—the creation of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Today, the NIMH continues “to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery, and cure.” The Institute prides itself on its research that brings the country a better understanding of these problems, and it uses its research and discoveries to prove that “breakthroughs in science can become breakthroughs for all people with mental illnesses.” Every military conflict exacts mental costs, but the servicemembers who lobbied for the NMHA demonstrated that their psychological issues demanded as much national attention as physical disabilities and should not be stigmatized. They acted on that conviction to begin the process that completely overhauled America’s approach to mental health.Footnote 46

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article, book, or presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.