Introduction

On June 26, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down United States v. Windsor (2013). The landmark case invalidated the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as excluding same-sex partners for purposes of federal law. In dissent, Justice Scalia argued the decision robbed the winners “of an honest victory” through the legislative process, which threatened the legitimacy of their newly recognized rights. Activists predicted a more visceral response. Shortly after the decision, Kate Kendell, executive director for the National Center for Lesbian Rights, warned that past civil rights victories in the courts had produced violent resistance, adding, “[w]e are just seeing the beginning … [of] backlash. It will get worse before it gets better” (quoted in Elliott Reference Elliott2015).

Does turning to the courts cause backlash as Scalia and Kendell imply? This question hinges on the causal effects of litigation, so the answer partly depends on whether politics would have been different in the shadow of alternative modes of policymaking. It is certainly possible. Public policy scholars agree that different policymaking modes engender distinct politics (e.g., Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Campbell Reference Campbell2012), while public law scholars recognize litigation as a form of policymaking with characteristic costs (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1977; Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin1998; Kagan Reference Kagan2019). One acknowledged risk of litigation is backlash: counterproductive reactions to litigation and judicial decisions that run the gamut from violence to political countermobilization, policy reversals, scornful media coverage, and/or negative attitudes toward courts, rights, or claimants (e.g., Post and Siegel Reference Post and Siegel2007; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008; Gash Reference Gash2015; Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Barnes and Hevron Reference Barnes and Hevron2018). Concerns about backlash, moreover, are not limited to high-profile constitutional cases. In his analysis of American-style litigation – “adversarial legalism” – Kagan finds one of its distinguishing features is “more political controversy about legal rules and institutions” (Reference Kagan2019: 8). Recognizing that backlash may follow litigation, however, leaves open the critical question of whether a similar reaction would have emerged if claimants had not litigated.

Within the sprawling backlash literature, some scholars have sought to test the effects of pursuing the same policy through litigation versus its alternatives. Most of this “venue effects” literature focuses on the Supreme Court’s relative capacity to confer legitimacy on policies. Results have been mixed. Several studies find the “cult of the Court” engenders greater policy support among the public than Congress, state legislatures, ballot initiatives, agencies and various “non-court” actors, such as high school principals (Mondak Reference Mondak1992; Clawson, Kegler and Waltenburg Reference Clawson, Kegler and Waltenburg2001; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2005; Bartels and Mutz Reference Bartels and Mutz2009). Some even find that the Court can persuade groups disinclined to agree with it (e.g., Gibson Reference Gibson1989). Others question the Court’s ability to change attitudes (Marshall Reference Marshall1987; Le and Citrin Reference Le, Citrin, Persily, Citrin and Egan2008; Gash and Gonzales Reference Gash, Gonzales, Persily, Citrin and Egan2008; Hanley, Salamone, and Wright Reference Hanley, Salamone and Wright2012). Some see little evidence of public opinion backlash against the Court while legislatures and referenda have a greater effect among some groups (e.g., Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). In two studies that look beyond the Supreme Court, Gash and Murakami (Reference Gash and Murakami2015) find significantly higher levels of support for educational funding policies from state legislatures and ballot initiatives than state courts, while Woodson (Reference Woodson2019) finds decisions from state supreme courts and the U.S. Supreme Court engender similar perceptions of legitimacy.

We seek to add to this literature on several fronts. First, we explore venue effects within injury compensation policy, which features significant amounts of litigation, offers multiple remedies (some rooted in litigation, others not), affects millions of Americans, and plays an ongoing role in filling gaps in the patchy U.S. social safety net. Focusing on ordinary tort litigation builds on Gash and Murakami’s (Reference Gash and Murakami2015) and Woodson’s (Reference Woodson2019) analyses of state courts and helps balance the literature’s overall emphasis on Supreme Court decisions and high-profile issues.

Second, instead of framing the underlying institutional choice between courts and legislatures (or ballot initiatives, agencies or “non-court” actors), we use the “dispute tree” from the sociolegal literature to structure the choice in terms of various sources of compensation, including asking family for help, hiring a lawyer to write a demand letter, filing a claim with a government program, or filing a lawsuit. As elaborated below, this novel application of the dispute tree is well suited to studying venue effects in injury compensation policy and avoids questions about the plausibility of positing a stark choice between policymaking forums in our system of “separated institutions sharing powers” (Neustadt Reference Neustadt1990: 34).

Third, we explore the impact of the choice of remedy on attitudes toward individual claimants as opposed to the legitimacy of institutions, policies, or specific court decisions (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2005; Woodson Reference Woodson2019). This builds on several studies that explore the impact of the Supreme Court’s marriage equality decisions on attitudes toward members of the LGBTQ community (compare Flores and Barclay Reference Flores and Barclay2016, Tankard and Paluck Reference Tankard and Paluck2017 with Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). We examine a complementary issue: whether the decision to litigate itself engenders negative reactions, which speaks to perceptions of everyday litigation that underlie its legitimacy (Tyler Reference Tyler2003, Reference Tyler2006, Reference Tyler2019) and offers insight into what Gash and Murakami (Reference Gash and Murakami2015: 682) call the “opportunity cost” of litigation in terms of attitudes. Negativity toward claimants, in turn, can contribute to backlash in tort law on other dimensions by undermining the willingness of jurors to recognize claims, reinforcing negative coverage of tort claimants, and adding political fodder to campaigns to limit access to the courts (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004; MacCoun Reference MacCoun2006; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels and Martin2015; see generally Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016).

Using a large-N survey experiment, we find significantly more negative attitudes toward injury victims who filed lawsuits versus other types of claims, even though our subjects did not perceive the underlying claim as frivolous and favored the claimant taking some action. The decision to file a lawsuit had a much greater effect than the choice of other remedies, including going to family for help, hiring a lawyer to write a demand letter, and filing a claim with a government program. Under these circumstances, our subjects were not particularly anti-claimant, anti-hiring a lawyer, or anti-government, but rather anti-litigant.

Case selection

A promising area for exploring venue effects would feature considerable amounts of litigation as well as remedies that do not involve the courts, allowing a comparison of the consequences of lawsuits and their alternatives. Injury compensation policy checks these boxes. Tort litigation is prevalent. From June 2021 to June 2022, tort cases made up more than a third of all federal civil cases (105,267 of 293,762), far exceeding the number of cases in civil rights (39,592), Social Security benefits (13,347), intellectual rights (12,411), and immigration (6,611) (Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics 2022, Table C-2). Of course, federal cases are only a small slice of all litigation. In 2018, an estimated 624,000 tort cases were filed in state courts, which translates to roughly one suit per minute, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week (State Court Caseload Digest 2018 Data: 7).

Injury compensation policy also features diverse remedies. As a threshold matter, injury victims can forgo claims and “lump” their injuries, which many do (Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980; Brennan et al. Reference Brennan, Leape, Laird, Liesi Hebert, Lawthers, Newhouse, Weiler and Hiatt1991; Kritzer Reference Kritzer2011; Engel Reference Engel2012). They also may avoid the formal claiming process and practice “self-help” by, for example, seeking assistance from family members or directly threatening to make a claim as part of “bargaining in the shadow of the law” (Mnookin and Kornhauser Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979; Black and Baumgartner Reference Black and Baumgartner1987).

If victims seek compensation through formal channels, they have options. If injured at work, they would probably file a claim under state workers’ compensation programs: government-mandated “no fault” programs for workplace injuries provided by employers. If the injury occurred at home, workers’ compensation laws would not apply. Depending on the victim’s age and the injury’s severity, a separate set of overlapping remedies might come into play, including employer-provided or privately purchased insurance, state health and disability insurance, and Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security Disability Insurance. Separate programs exist for specific victims and types of injuries, including trust fund compensation schemes for children who fall ill after being vaccinated, sufferers from radiation fallout, coal miners with black lung disease, babies with birth defects, victims of the September 11 terror attacks, and the list goes on. This hodgepodge has been grafted unevenly onto a dynamic tort system (Kagan Reference Kagan2019), creating densely layered potential remedies (see Burke and Barnes Reference Burke and Barnes2018).

Finally, tort’s policy significance is worth stressing. All industrialized nations must address how to compensate victims of unexpected losses stemming from unforeseen defects in products, economic dislocations, negligence, and reckless conduct (Friedman Reference Friedman2019). In the United States, tort law represents a substantial part of our overall injury compensation policy, determining which claims are worthy, who pays, and how much (Kagan Reference Kagan2019). It covers everything from routine accident, medical malpractice, and negligence cases to complex “mass tort” cases addressing defective products and public health crises, such as the opioid epidemic (Gluck, Hall, and Curfman Reference Gluck, Hall and Curfman2018), fallout from tobacco use (Derthick Reference Derthick2012), asbestos (Barnes Reference Barnes2011), and others (Nagareda Reference Nagareda2007).

Research design

Our analysis compares the effects of different claiming options. To frame these alternatives, we use the “dispute tree” from the sociolegal literature, which is designed to map injury victims’ claiming choices (see Albiston et al. Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014; see also Nielsen and Nelson Reference Nielsen, Nelson, Nielsen and Nelson2005). As seen in Figure 1, injury lies at its root. To “climb” the tree, victims generally will have a grievance related to the injury, which assigns some blame to a third party. (You can also imagine claimants who act in bad faith and pursue claims in the absence of an injury or legitimate grievance.) Aggrieved victims then must decide whether to seek compensation and, if so, which remedy to pursue, such as asking family for help, hiring a lawyer to write a demand letter, filing a claim with a government program, or bringing a lawsuit.Footnote 1

Figure 1. The Dispute Tree.

A few points bear emphasis. First, the dispute tree’s distinct branches reflect the law’s conceptualization of remedies as separate sources of compensation as opposed to a single set of interlocking options. So, as a general matter, the “collateral source rule” allows accident victims to claim damages even for losses covered by insurance and bars juries from hearing about payments from other sources (Kagan Reference Kagan2019: 155–156, 175).

Second, context matters. For example, workers’ compensation programs usually prohibit employees from suing employers for workplace injuries in tort. However, in California, the nation’s largest workers’ compensation system, victims of occupational disease may sue if they believe that risks were concealed. So, asbestos workers in California were allowed to sue their employers in tort even though they had already received workers’ compensation benefits for their injuries (Aerojet General Corp. v. Superior Court (1986) 177 Cal.App.3d 950, 956; see generally California Labor Code Section 3602(b)(2)). The order of claims may also vary. Some might threaten litigation before taking any other action. They might pursue non-exclusive remedies simultaneously, as when someone hires a lawyer to write a demand letter and files a lawsuit to play different remedies off one another. Others might proceed sequentially by first asking a lawyer to send a demand letter and, if negotiations falter, file a lawsuit, in order to ratchet pressure.

Third, we could add alternatives or steps within the branches. We could include different programs within the “government program” option or different causes of action within the “lawsuit” category. We could elaborate the “lawsuit” branch by adding discovery, pretrial motions, settlement, trial, and appeal and the “hire a lawyer” branch by distinguishing steps in settlement negotiations. The point is that, although we can conceive of the dispute tree with varying levels of nuance, its basic structure would remain. The process would typically start with an injury, move to grievance, and then widen to reflect different claiming options stemming from the layered U.S. injury compensation system.

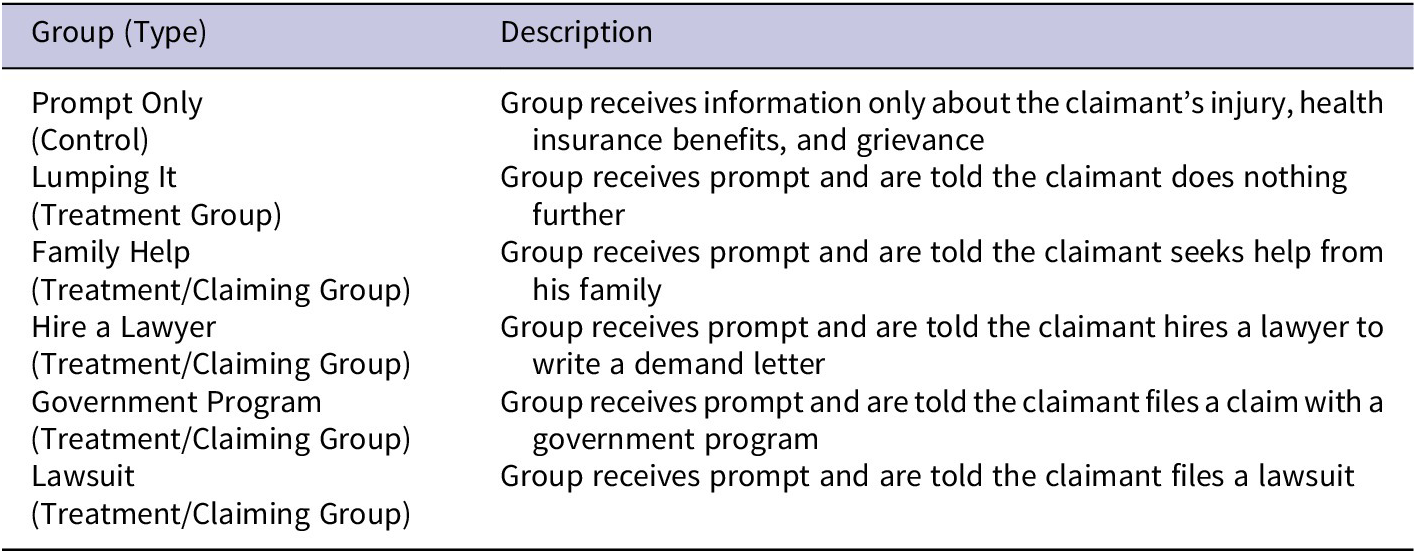

Finally, scholars have generally used the dispute tree descriptively, charting patterns of claiming in various policy areas (e.g., Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980; Brennan et al. Reference Brennan, Leape, Laird, Liesi Hebert, Lawthers, Newhouse, Weiler and Hiatt1991; Kritzer Reference Kritzer2011; Engel Reference Engel2012). By contrast, as elaborated below, we use it to delineate control and treatment groups as part of a survey experiment (see Table 1). Because the dispute tree aims to capture actual claiming practices, it enhances the external validity of our experiment and avoids some questions about the framing of other venue effects studies. Price and Keck (Reference Price and Keck2015), for example, argue interest groups do not have a simple choice between courts and other policymaking forums. As a strategic matter, it seems unrealistic to assume groups would unilaterally abandon litigation and allow rivals to choose the forum and framing of cases in contested policy areas. Moreover, ostensibly allied interests may face coordination problems. According to Klarman (Reference Klarman2012), leading rights groups feared that pursuing marriage equality though the courts could backfire. But they did not unilaterally control the decision to litigate, as gay couples who wanted to marry proceeded without them. Finally, in a system of overlapping policymakers, choosing legislation does not preclude litigation or agency action, as courts and agencies inevitably shape the meaning of legislation though adjudication and implementation. It is not surprising, then, that sophisticated groups often combine lobbying and litigation (Melnick Reference Melnick1994; McCann Reference McCann1994; Epp Reference Epp2009; Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2015). For all of these reasons, positing a stark choice among policymaking venues may be problematic.

Table 1. Dispute Tree: Control and Treatment Groups

Hypotheses

Using the groups in Table 1, we can set forth several hypotheses about attitudes toward claimants who choose different options. As a threshold matter, aggrieved injury victims must decide between seeking compensation or “lumping” their injuries. Respondents may equate lumping it with admirable self-reliance and stoicism, while seeing the seeking of compensation as part of a whiny “culture of complaint” (e.g., Hughes Reference Hughes1993). This view implies an anti-claiming hypothesis:

H1: Anti-Claiming Hypothesis. All things being equal, respondents in the Lumping It Group will have significantly more positive attitudes toward the claimant than respondents in the Control Group or the groups seeking compensation (combining the Family Help, Hire a Lawyer, Government Program, and Lawsuit Groups).

If injury victims seek compensation, the next issue concerns attitudes toward claimants who choose different options. Of course, the choice of remedy may not matter. From a simple economic perspective, the underlying claiming mechanisms should be irrelevant. Why should anyone think differently of someone who receives $10,000 from a government program versus a lawsuit? This logic suggests a null hypothesis:

H2: Null Claiming Hypothesis. All things being equal, there will be no significant difference between respondents’ attitudes toward the claimant in the Family Help, Hire a Lawyer, Government Program, and Lawsuit Groups.

Contrary to this null hypothesis, the general policy feedback literature suggests different remedies will yield different political reactions (Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Campbell Reference Campbell2012). Moreover, Linos and Twist (Reference Linos and Twist2017) argue that media coverage is crucial to shaping public opinion backlash. Combining experiments and longitudinal analysis, they show positive “one-sided” coverage of decisions significantly bolstered attitudes toward controversial cases in health care and immigration. This argument accords with the political communication literature, which demonstrates how stories shape the way we learn about the world (Iyengar Reference Iyengar1991) and place issues in a “field of meaning” (Scheufele Reference Scheufele1999; see also Entman Reference Entman1993; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007).

The literature on media coverage of tort suggests this field of meaning tilts against the tort system and its participants. There is a long history in America of “lawyer jokes,” deriding personal injury lawyers as “ambulance chasers,” and widely circulated “tort tales”: dramatic anecdotes that exaggerate the system’s cost, inefficiency, and arbitrariness, such as the infamous McDonald’s coffee case (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004; McCann and Haltom Reference McCann and Haltom2004; Malhotra Reference Malhotra2015; Barnes and Hevron Reference Barnes and Hevron2018). These stories single out the tort system, making it seem especially ridiculous and out of control. They may also have disproportionate effects on public perception because of the “availability heuristic,” a cognitive rule of thumb in which people infer that the ease of recalling events reflects their actual likelihood (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984). Under this heuristic, the more dramatic and shocking an event, the more likely people will believe similar events will happen. According to this logic, people will infer that easy-to-remember “horror stories” about specific tort cases typify the entire system.

Media coverage of seemingly outrageous jury awards and big monetary settlements is likely to persist. The media naturally gravitates to dramatic events (Bennett Reference Bennett2015). The modal recovery in tort is zero, while all the extreme (and newsworthy) cases feature large verdicts against defendants, which may skew coverage toward negative narratives of “break-the-bank” jury awards (Bailis and MacCoun Reference Bailis and MacCoun1996; Garber and Bower Reference Garber and Bower1999; MacCoun Reference MacCoun2006). Consistent with this argument, scholars find that tort tales are the most visible part of a broader pattern of lopsided, negative media coverage, depicting grasping tort litigants rushing to the courts to cash in their litigation “lottery tickets” (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004).

More recent studies explore whether this type of negative coverage reflects a particular bias against litigation or general reporting conventions that favor dramatic, negative anecdotes (Bennett Reference Bennett2015), regardless of institutional setting. For instance, we used a natural experiment to compare newspaper accounts of asbestos tort litigation and the black lung compensation fund, a no-fault social insurance program (Barnes and Hevron Reference Barnes and Hevron2018; Reference Barnes and Parker2023). We argued that these regimes feature similar time frames, injuries, stakeholders, and criticisms by experts, who found that both are inefficient, costly, and prone to frivolous claims. Despite these similarities, coverage of asbestos litigation was significantly more negative and episodic than the black lung program.

In sum, just as one-sided positive coverage might generate positive reactions, the drumbeat of critical stories about the tort system may have primed people to be particularly skeptical about personal injury litigants, suggesting an anti-litigant hypothesis:

H3: Anti-litigant Hypothesis. All things being equal, respondents in the Lawsuit Group will have significantly more negative attitudes toward claimants than those in the Control Group and each non-lawsuit claiming group (the Family Help, Hire a Lawyer, Government Program Groups).

Data and methods

Overview

We follow a long line of scholars who use survey experiments to examine venue effects (e.g., Mondak Reference Mondak1992; Clawson, Kegler, and Waltenburg Reference Clawson, Kegler and Waltenburg2001; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2005; Bartels and Mutz Reference Bartels and Mutz2009; Fontana and Braman Reference Fontana and Braman2012; Gash and Murakami Reference Gash and Murakami2015; Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Woodson Reference Woodson2019). While survey experiments are not a panacea, they help address potential omitted variable bias better than observational studies and provide some leverage over the counterfactual of what would have happened in the absence of litigation by randomly assigning claiming choices in a reasonably controlled environment (Dunning Reference Dunning2012; Hevron Reference Hevron2018).

Survey design and implementation

We ran our survey in January 2021 online using the subject pool from Qualtrics (without quotas), which is the most demographically and politically representative among leading online convenience samples in the United States (Boas et al. Reference Boas, Christenson and Glick2020). The survey employs a posttest-only control group design that randomly assigns subjects to a control or treatment group, allowing us to compare attitudes toward different choices of remedy. The survey was intended to take about ten minutes, and subjects were paid $5 upon completion.

The survey was conducted in waves. On January 7 and 8, we fielded a soft launch, collecting 100 pilot responses to troubleshoot problems. After reviewing the results, we resumed on January 20 and concluded on January 22. We included several quality checks. For example, we automatically dropped respondents who completed the survey in less than one-half the median soft launch time. Prior to randomization, we also tested comprehension and attentiveness using a “screener” question designed by Berinsky, Margolis, and Sances (Reference Berinsky, Margolis, Sances and Warshaw2019; see also Berinsky et al. Reference Berinsky, Margolis and Sances2014; cf. Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018). The screener question was unrelated to our topic and focused solely on ensuring that participants fully read the prompts provided to them.Footnote 2 Participants who answered this question incorrectly were dropped. There were 1,007 participants in total after screening.Footnote 3

Prior to assignment, subjects were asked a series of demographic questions, including questions about their gender, education, race, and political ideology. (Appendix 1 summarizes the sample’s demographic characteristics.) After these questions, subjects read about a hypothetical worker, Joe, who was diagnosed with a serious illness associated with chemicals that he used at work. The prompt went on to say:

Joe believes that his company should have told its employees that these chemicals were risky. He thinks that his employer didn’t take adequate steps to do this while he worked there. Joe’s company argues that nobody knew about these risks at the time Joe worked there and that it followed the rules that were in place.

Despite the fact that Joe worked for the company for a long time and has some health insurance, his insurance does not fully cover his doctors’ bills and medical expenses.

The prompt ends by presenting a list of Joe’s potential claiming options. Subjects were then randomly assigned to a control group, which received only the prompt, or one of five treatment groups: (1) forego pursuing compensation and lump it (“Lumping It”); (2) ask his family for help (“Family Help”); (3) hire a lawyer to write a letter to his former company seeking compensation (“Hire a Lawyer”); (4) file a claim with a government program for workers injured on the job (“Government Program”); or (5) file a lawsuit against his former company (“File a Lawsuit”). Following assignment, participants answered a series of post-test questions about their feelings toward Joe, his level of injury and fault, his mode of seeking compensation, and the justifiability of different claiming options.

Remember workers in states such as California can file (and have filed) workers’ compensation claims and tort suits when they believe their employer’s concealment of risks exacerbated their injuries. Note also that underinsured workers suing a corporation are likely to be sympathetic (see generally Hans Reference Hans2000). As a result, the survey reflected actual claiming scenarios that maximized options under the dispute tree as a matter of law while seeking to create a challenging empirical test for the Anti-Litigant Hypothesis.

Measurement

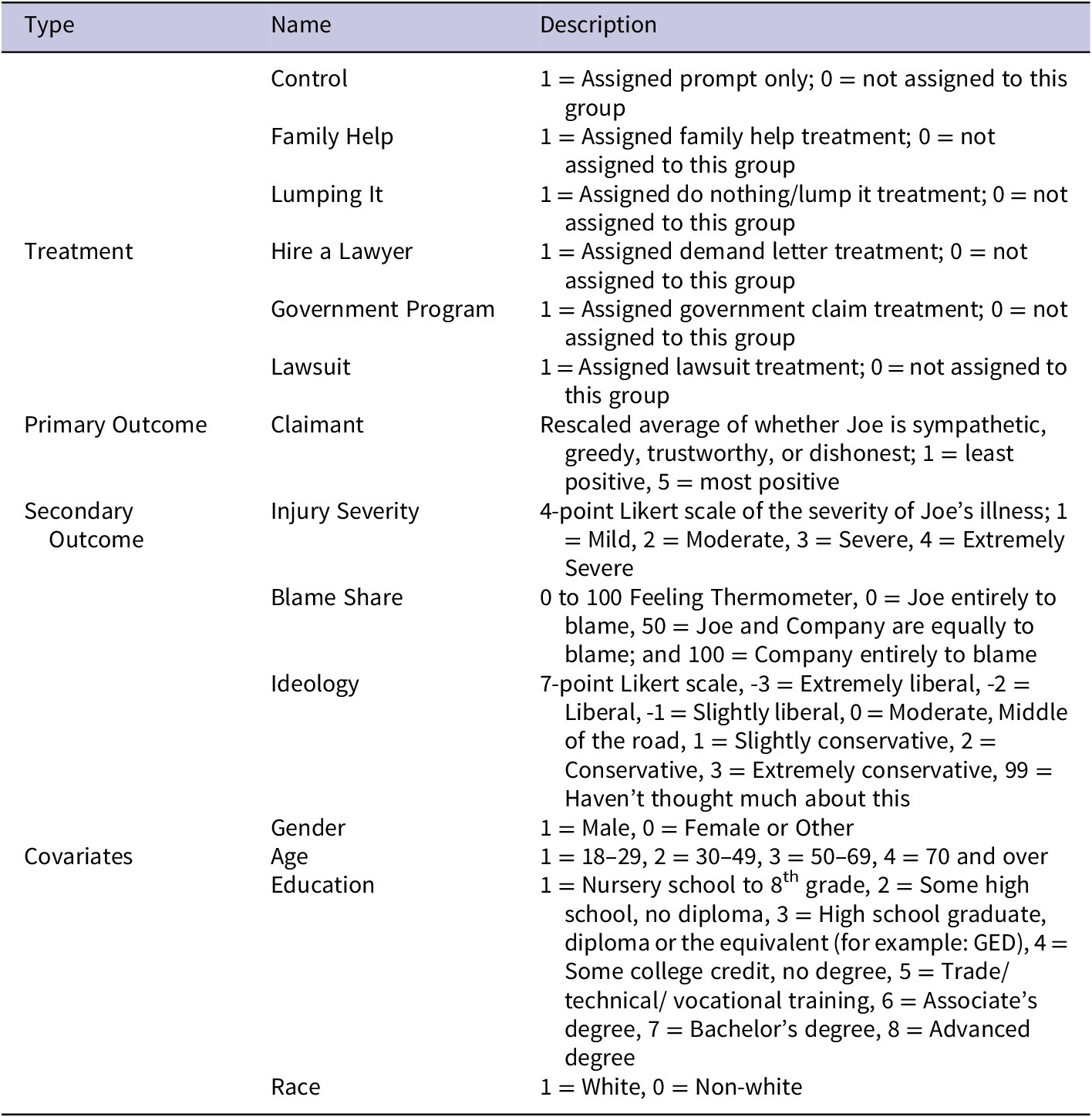

We created dummy variables for each treatment option and measured the primary outcome variable, attitudes toward Joe, in three steps. First, after receiving the treatment, we asked (in random order) whether Joe seemed (1) sympathetic, (2) trustworthy, (3) dishonest, and (4) greedy. Second, we rescaled these responses from negative to positive attitudes toward Joe (from 1, the least positive, to 5, the most positive). Finally, we averaged the rescaled responses to create the Claimant outcome variable.Footnote 4 These measures, along with the measures of our secondary variables and covariates, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of Key Variables and Measures

Randomization

One hundred and seventy-six subjects were randomly assigned to the Control Group, 164 to the Lumping It Group, 162 to the Family Help Group, 168 to Hire a Lawyer Group, 163 to the Government Program Group, and 174 to the Lawsuit Group. As shown in Appendix 2, the randomization performed quite well, producing groups that are similar with respect to the pretreatment demographic characteristics that might affect attitudes toward litigation.

Findings

Perception of injury and grievance

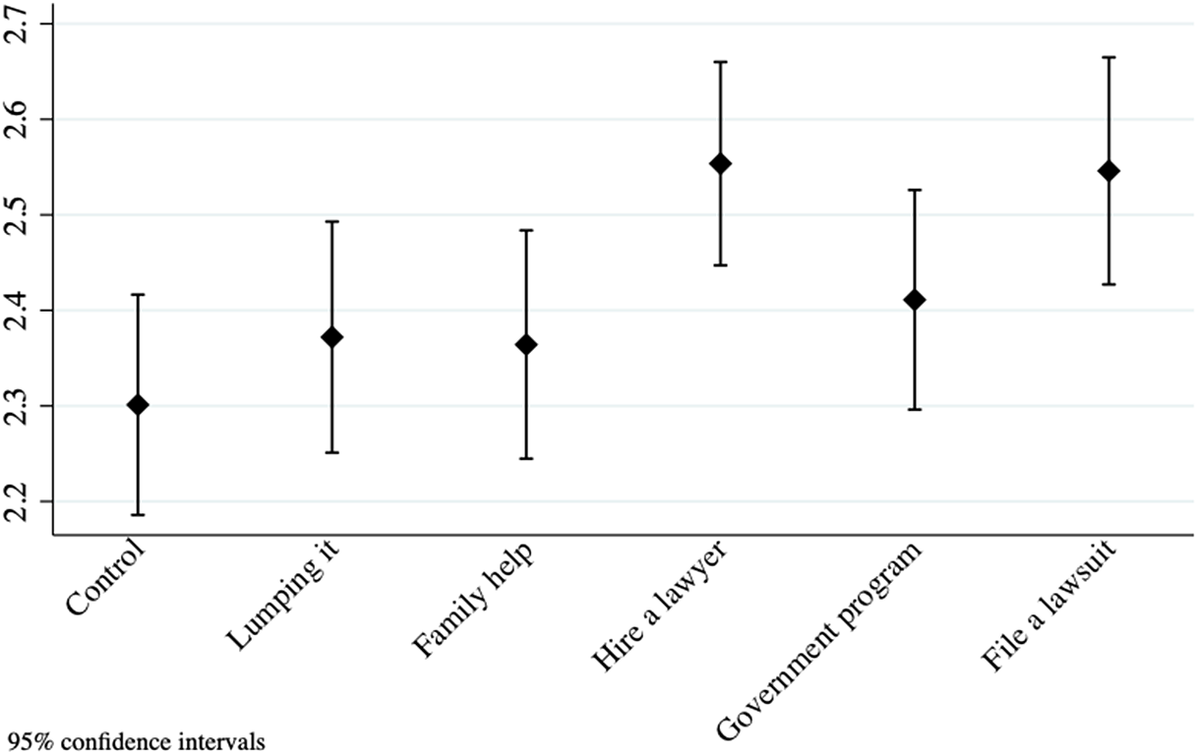

Before turning to the hypotheses, we begin with perceptions of injury and blame, which lie at the base of the pyramid and relate to whether our subjects viewed Joe’s claim favorably, thereby creating a “less likely” case for the Anti-Litigant Hypothesis as intended. Consistent with this goal, our subjects were sympathetic to Joe’s claim, believing on average that he was moderately to severely injured and the Company was mostly at fault. Figure 2 reports the mean perceptions of the severity of Joe’s illness with 95 percent confidence intervals for each group. The results ranged from 2.30 to 2.55 on a four-point scale, where 1 is mild illness, 2 is moderate illness, 3 is severe illness, and 4 is extremely severe illness. Specifically, the Control Group was on the low end (2.30); the Lawsuit and Hire a Lawyer Groups were at the high end (2.54 and 2.55, respectively); and the Family Help and Government Program Groups fell between (2.36 and 2.41, respectively).

Figure 2. Mean Perception of Injury Severity Across Groups (n = 1007).

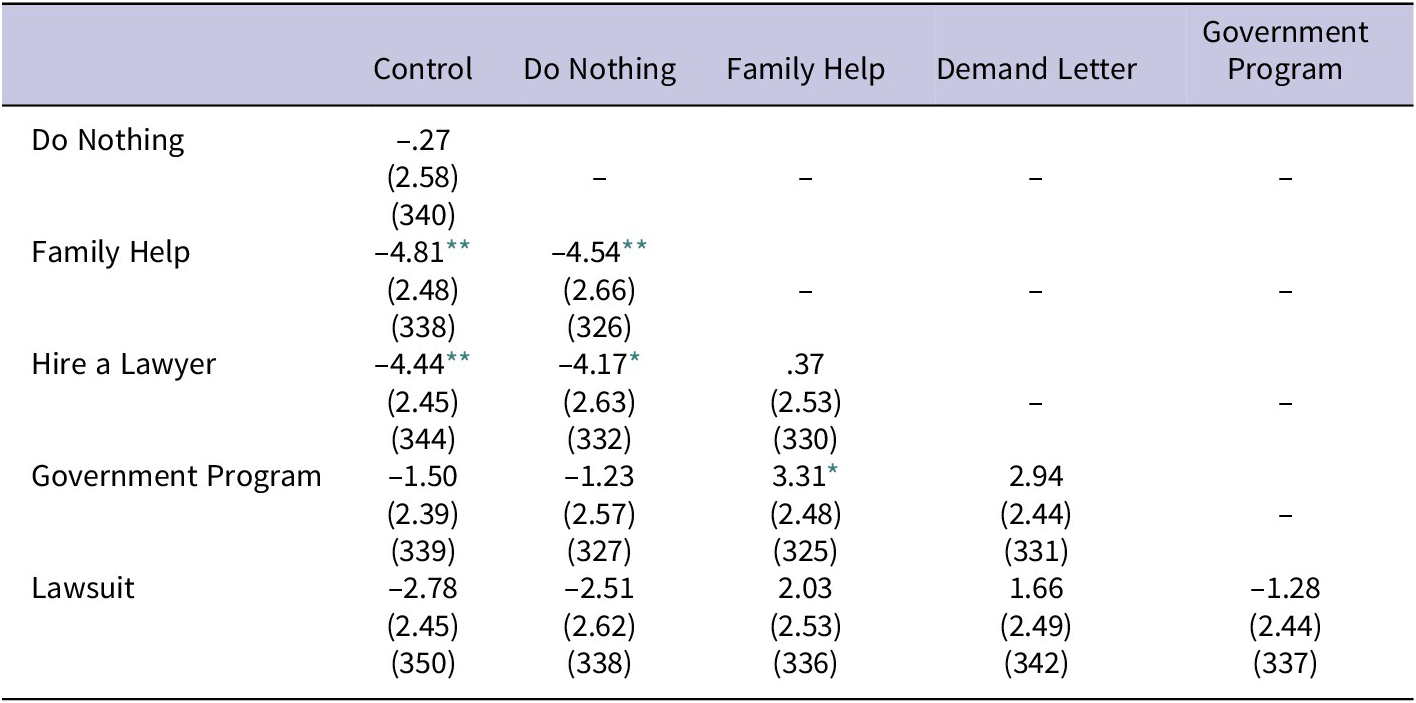

Table 3 sets forth differences in means. (Remember that all confounding variables that may explain the differences in means across these groups beyond our randomized conditions are “controlled for” through the experimental design.) The mean perception of Joe’s injury in the Lawsuit and Hire a Lawyer Groups were statistically the same. Both were higher than the Control Group beyond the .01 level of significance and the other groups to at least the .10 level. So, if anything, our respondents thought claimants who hired lawyers and filed lawsuits were more injured than other types of claimants. (As a robustness check for each component of our analysis, we ran regressions with and without covariates using the Control Group as the missing category. See Appendices 3 through 6.)

Table 3. Differences in Mean Perceptions of Illness Severity Across Groups

Note: Standard errors and N in parentheses. All t-tests assume unequal variance.

* p ≤ .10

** p ≤ .05

*** p ≤ .01

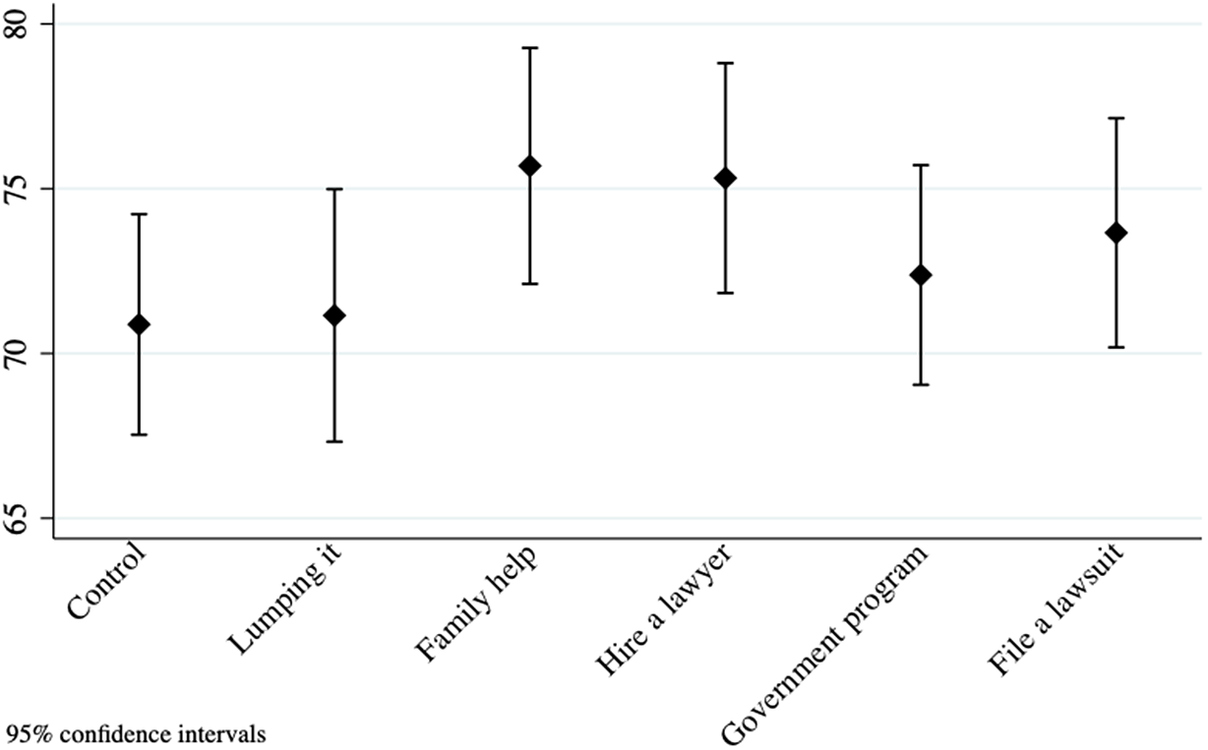

Figure 3 portrays the mean assignment of blame across the groups on a scale from 0 to 100 with 95 percent confidence intervals, where 0 is entirely Joe’s fault, 50 is equal blame, and 100 is entirely the Company’s fault. The results ranged from 71 to 76, indicating that our subjects placed the majority of blame on the Company, which is consistent with viewing Joe’s claim as meritorious. As seen in the last row of Table 4, the differences in the mean assignment of blame in the Lawsuit Group versus all other groups were statistically equivalent.

Figure 3. Mean Assignment of Blame Across Groups (n = 1007).

Table 4. Differences in Mean Assignment of Blame Across Groups

Note: Standard errors and N in parentheses. All t-tests assume unequal variance.

* p ≤ .10

** p ≤ .05

*** p ≤ .01

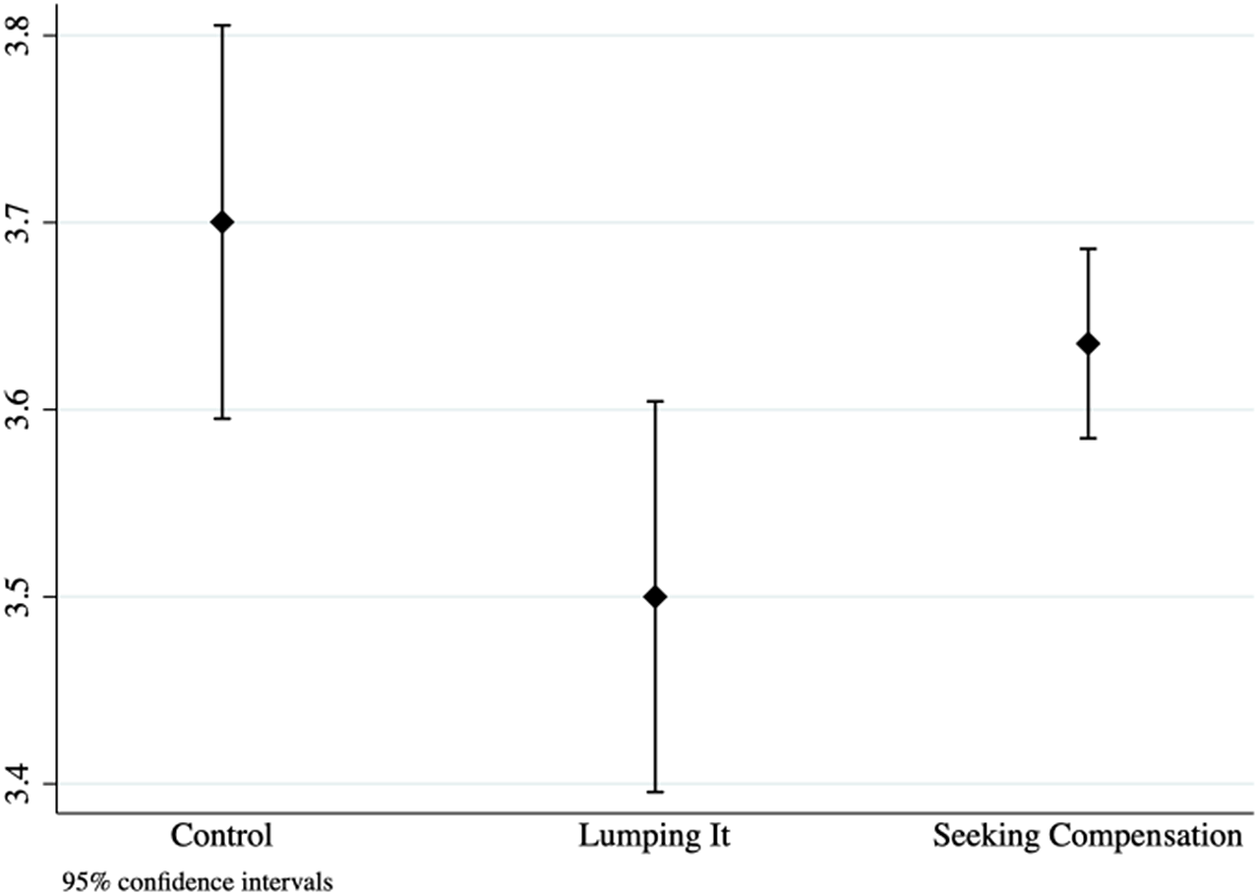

Anti-claiming hypothesis

The next issue concerns attitudes toward claimants who seek compensation versus “lumping” their grievances. To explore this critical juncture, we compared opinions of Joe across the Control, Lumping It, and Seeking Compensation Groups. (This final group averaged responses from the Family Help, Hire a Lawyer, Government Program and Lawsuit Groups.) Figure 4 depicts mean perceptions of Joe across these groups with 95 percent confidence intervals, and Table 5 reports differences in means. Contrary to the Anti-Claiming Hypothesis, subjects viewed Joe more positively in the Control and Seeking Compensation Groups than those in the Lumping It Group. The mean opinion of Joe in the Control Group was 3.70, 3.64 in the Seeking Compensation Group, and 3.50 in the Lumping It Group. The average opinion of Joe in the Control and Seeking Compensation Groups was statistically equivalent, whereas the drop in opinion from these groups to the Lumping It Group was statistically significant to at least the .05 level.

Figure 4. Mean Perception of Claimant: Control, Lumping It, and Seeking Compensation Groups (n = 1007).

Table 5. Differences in Mean Perceptions of Claimant: Control, Lumping It, and Seeking Compensation Groups

Note: Standard errors and N in parentheses. All t-tests assume unequal variance.

* p ≤ .10

** p ≤ .05

*** p ≤ .01

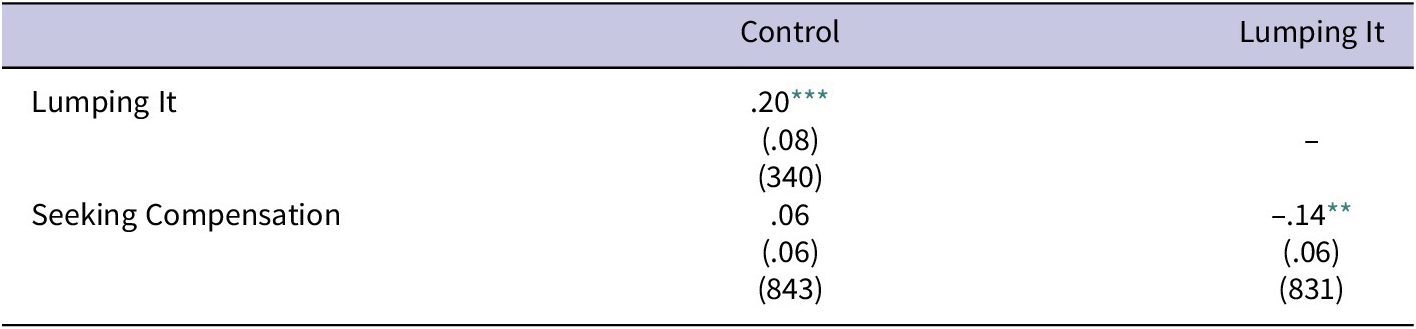

Null claiming hypothesis

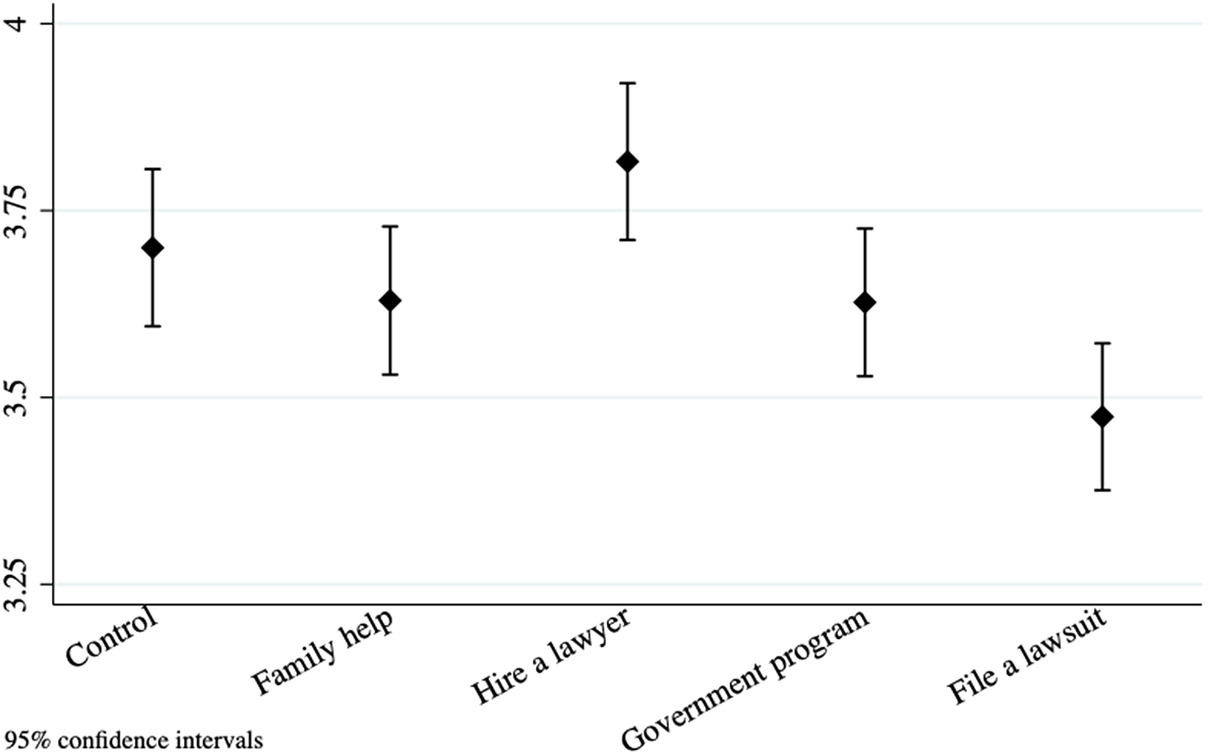

Moving to the dispute tree’s upper branches raises questions about the significance of choosing different remedies. Figure 5 summarizes the mean opinion of Joe for each claiming group as well as the Control Group with 95 percent confidence intervals. Contrary to the Null Claiming Hypothesis, attitudes toward Joe significantly varied across claiming groups. The Hire a Lawyer Group had the highest opinion of Joe (3.82); the Lawsuit Group had the lowest opinion (3.47); and the Family Help and Government Program Groups fell in the middle, sharing the same view of Joe (3.63). It is worth noting that opinions also varied in comparison to the Control Group, as the Hire a Lawyer Group attitudes toward Joe were higher than the Control Group (3.82 versus 3.70); the Lawsuit Group attitudes were lower (3.47 versus 3.70), and the others were about the same (3.63 versus 3.70).

Figure 5. Mean Perception of Claimant Across Control and Claiming Groups (n = 843).

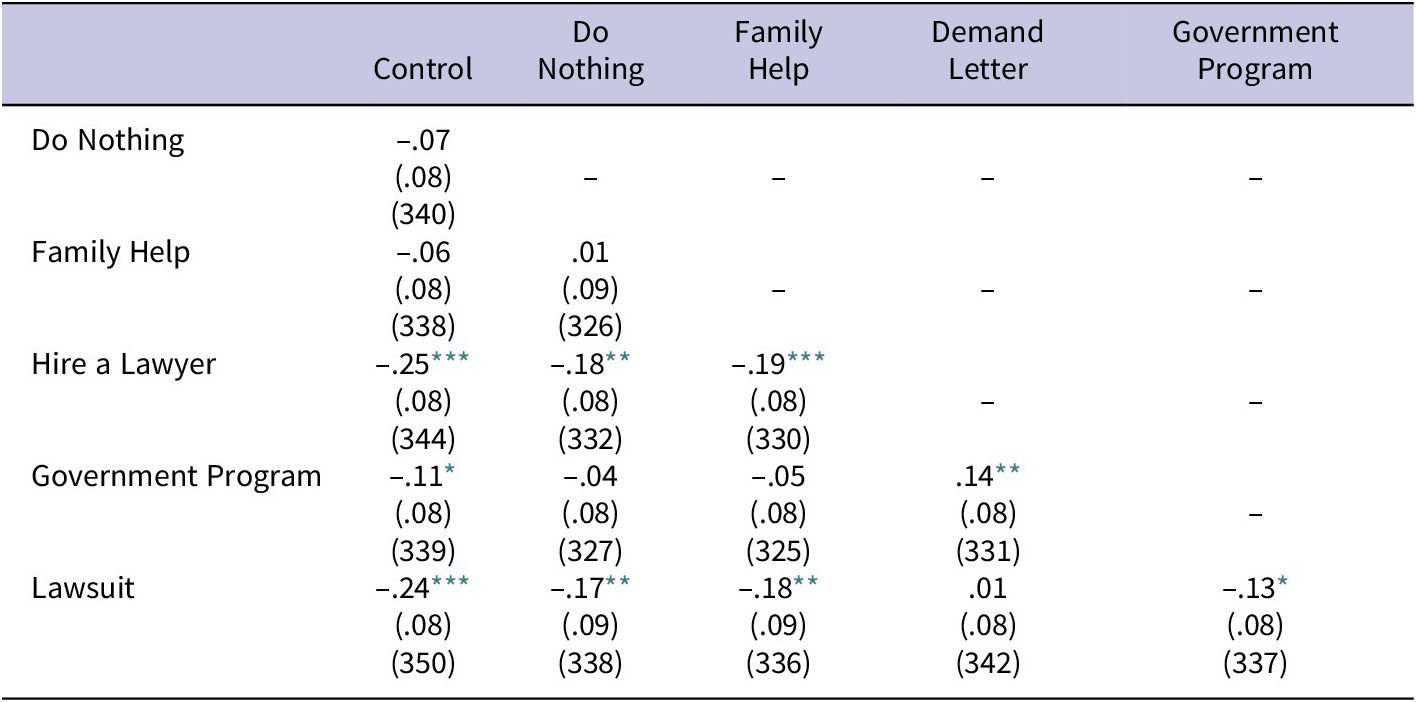

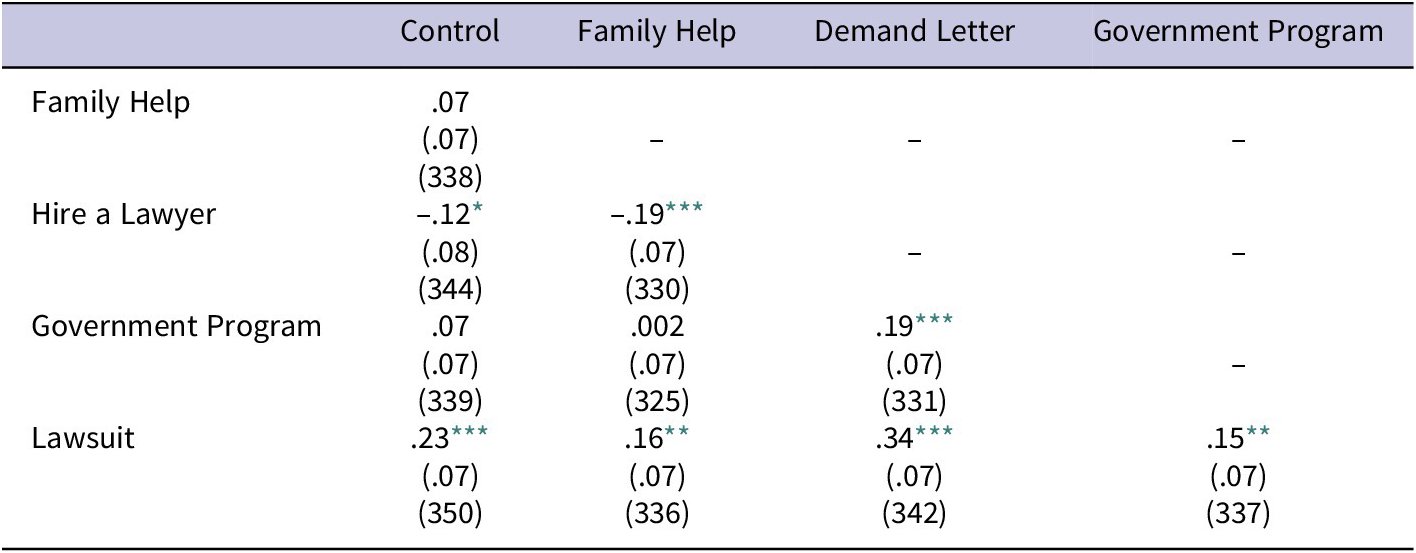

Table 6 reports differences in means. Recall that the Null Claiming Hypothesis predicts equivalent attitudes toward Joe across the claiming options, but as seen in the three claiming group columns in the Table, five of six pairs of claiming options produced statistically significant differences to at least the .05 level. (The exception were attitudes in the Government Program and Family Help Groups, which were statistically the same.)

Table 6. Differences in Mean Attitudes Toward Claimants Across Claiming Groups

Note: Standard errors and N in parentheses. All t-tests assume unequal variance.

* p ≤ .10

** p ≤ .05

*** p ≤ .01

Anti-litigant hypothesis

The final issue under the dispute tree concerns the Anti-Litigant Hypothesis, which predicts that filing a lawsuit will trigger a particularly negative reaction toward Joe. Consistent with this prediction, as seen in Figure 5 above, the average view of Joe in the Lawsuit Group was the lowest among claiming groups: 3.47 compared to 3.70, 3.82, 3.63, and 3.63 in Control, Hire a Lawyer, Family Help, and Government Program Groups, respectively. These differences are statistically significant beyond the .05 level. (See Table 6.)

The relative sizes of the differences in means among the claiming options and the Control Group are also striking. The story lies in the first column of Table 6, which presents the differences between the Control and all claiming groups. It shows the mean difference between the Control and Lawsuit Group was .23 (3.70 versus 3.47), which is about double the next closest difference of .12 (between the Control and Hire a Lawyer Group, 3.70 versus 3.82) and more than triple the other claiming options (.07 or 3.70 versus 3.63 for both the Family Help and Government Program Groups).

Note also that our subjects’ attitudes toward Joe were not evenly distributed across the composite five-point scale. They were more normally distributed, so that the majority of responses on the claimant scale in the sample – 683 of 1007, or 68 percent – were clustered between 3 and 4. From this perspective, a shift of .23 is considerable. Digging a bit deeper, .23 represents half of the variance of the claimant responses in the sample (.46), while a .23 drop in a claimant score would move a respondent’s view of Joe from about the 50th percentile to about the 40th percentile in the sample.Footnote 5 Of course, none of these numbers address the duration of the effect or how the change in attitude would likely alter the respondents’ behavior. Exploring these questions requires further research.

Tort tale coverage as mechanism?

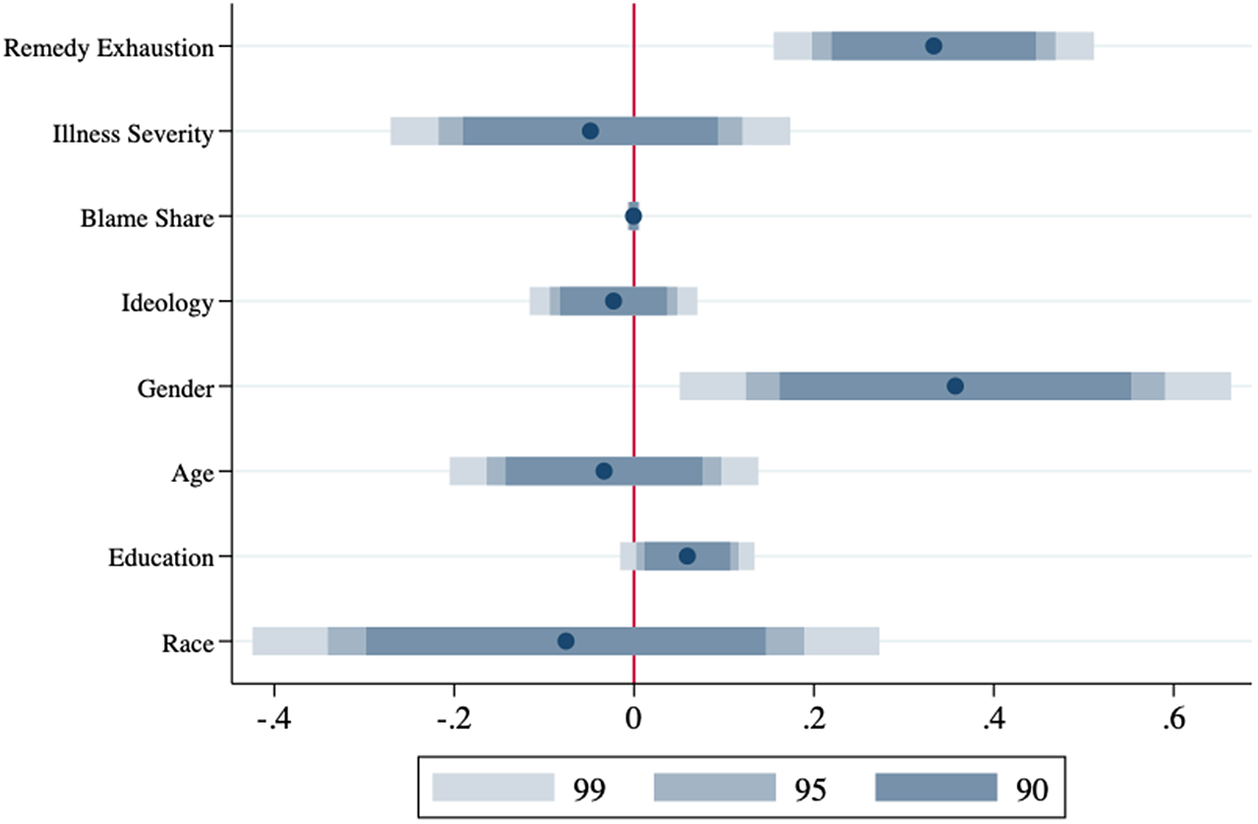

Our research does not directly address the mechanisms underlying the variation in attitudes. However, as discussed earlier, there are strong theoretical reasons to suspect negative tort tale coverage has primed our subjects to view personal injury litigants negatively. To probe this assumption on a preliminary basis, we conducted a secondary analysis of attitudes within the Lawsuit Group. The idea is that, if tort tales about greedy plaintiffs rushing to the courthouse were negatively shaping attitudes toward Joe, telling respondents he exhausted other remedies before filing a lawsuit should improve them.Footnote 6 This is not a foregone conclusion. It is theoretically possible that telling respondents that Joe struck out with his family, a demand letter, and a claim with a government program might erode confidence in the merits of his claim and make his decision to sue seem less justified.

To examine this issue, at the end of the survey, we asked subjects in the Lawsuit Group whether they agreed on a 1 to 5 scale (where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 5 is “strongly agree”) that Joe’s filing a lawsuit would be more justified after being informed of a series of nested claiming scenarios: (1) filing a lawsuit after failing to get compensation from his family; (2) filing a lawsuit after failing to get compensation from his family and a demand letter; and (3) filing a lawsuit after failing to get compensation from his family, demand letter, and government claim.Footnote 7 On average, the respondents’ level of agreement steadily increased after learning of each scenario. When told Joe filed a lawsuit after failing with his family, respondents’ mean level of agreement was 2.91. After being informed that he failed not only with his family but also after a lawyer wrote a demand letter, the mean level of agreement jumped to 3.33. It increased again to 3.56 after being told the final claiming scenario of filing a lawsuit after exhausting the family help, demand letter, and government program options. As seen in Figure 6, this effect of increasing information about the claiming process was significant beyond the .01 level, controlling for perception of injury, assignment of blame share, and our covariates. Although not part of our randomized experiment, this “dose effect” is consistent with the notion that attitudes toward Joe’s decision to litigate were not fixed and that negative assumptions about tort litigants rushing to the courts seemed relevant in shaping attitudes.

Figure 6. Coefficient Plot: Remedy Exhaustion Effect on Justifiable Action (n = 486).

Discussion

Do people turn on those who turn to the courts? Our survey experiment finds people have significantly more negative attitudes toward claimants who decide to sue compared to other remedies, even when they believe, on average, that the claimant was injured and not primarily at fault. Moreover, our subjects were not particularly opposed to injury victims hiring a lawyer, filing a claim with a government program, or seeking family help. Indeed, respondents had significantly more positive views of Joe when he sought compensation as opposed to lumping it. The bottom line was significant anti-litigant sentiment as opposed to anti-claim, anti-hiring a lawyer, or anti-government program attitudes. Put differently, rather than opposing specific court decisions or policies, our respondents negatively reacted to the decision to litigate. Negative perceptions of using the courts, even when underlying claims have merit, raises questions about the foundations of the legitimacy of everyday tort law (see Tyler Reference Tyler2003, Reference Tyler2006, Reference Tyler2019), which is troubling given its role in supplementing and filling gaps in the patchwork of American injury compensation programs (Burke and Barnes Reference Burke and Barnes2018; Kagan Reference Kagan2019).

Our experiment focuses on occupational disease, which is only one type of injury. However, we think similar dynamics are likely with other types of injury claims for several reasons. First, if people turn against litigants like Joe, who is seen as injured and not at fault, it seems likely that they would react negatively toward less sympathetic tort plaintiffs. Second, our admittedly preliminary analysis of attitudes within the Lawsuit Group suggests that negative media coverage about greedy tort plaintiffs rushing to the courts may be priming attitudes toward Joe. If so, negative narratives about tort claimants are not limited to workplace injuries; indeed, the paradigmatic tort tale involves a suit for injuries suffered from spilling a scalding cup of McDonald’s coffee (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004). Finally, our results resonate with studies that use divergent methods and data, which lends them some convergent validity. For example, our subjects’ anti-litigant views comport with Engel’s ethnography of attitudes in a small, Midwestern farming community, which finds particularly negative attitudes toward tort litigants (Engel Reference Engel1984). Our findings on opinion backlash against tort claimants also complement comparative studies and natural experiments that find political backlash against the tort system in the form of greater levels of countermobilization, interest group conflict in Congress, and negative media coverage of tort than its bureaucratic counterparts, as well as case studies of reform efforts designed to discourage the filing of tort claims regardless of their merits (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2015; Barnes and Hevron Reference Barnes and Hevron2018; see also Burke Reference Burke2002; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels and Martin2015; Kagan Reference Kagan2019).

Of course, the benefits of litigation may outweigh the risks of backlash. Given the multiple veto points in our policymaking process, tort may be the only viable option for compensation and holding wrongdoers accountable, despite its many shortcomings (see Kagan Reference Kagan2019). But even when litigation is the only practical alternative, practitioners must be mindful of kneejerk negativity toward their clients. Reflexively negative attitudes toward tort claimants can impact the willingness of juries to recognize claims (MacCoun Reference MacCoun2006; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels and Martin2015), reinforce exaggerated (and sometimes apocryphal) tort tale themes related to greedy litigants and frivolous lawsuits in public discourse (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004; McCann and Haltom Reference McCann and Haltom2004), and bolster ongoing lobbying efforts to limit access to the courts regardless of the merits of individual claims (Burke Reference Burke2002; Staszak Reference Staszak2015; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels and Martin2015; Burbank and Farhang Reference Burbank and Farhang2016). Indeed, a propensity toward policy backlash against tort claimants may be playing out in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the outset of the crisis, litigation began to percolate (Hussain Reference Hussain2020). Passengers sued cruise lines for negligently exposing passengers to the virus and, in some cases, preventing them from seeking treatment. Prisons and nursing homes faced similar suits. Although the total number of cases remained minor compared to other health crises, dozens of states have already passed laws limiting liability for COVID-related lawsuits, cutting off claims before they can be filed (Povich Reference Povich2021). Given these downsides, it is crucial to assess how to manage the risks of backlash in its various guises – public opinion, political, and policy – and build on our preliminary finding that framing litigation as a last resort can bolster attitudes toward worthy claims.

What about non-tort claims? A core lesson from the literature is that backlash varies across policy areas and over time within cases (compare, e.g., Klarman Reference Klarman1994, Reference Klarman2004, Reference Klarman2012; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008; Keck Reference Keck2009; Gash Reference Gash2015). Without a firmer grasp on the underlying mechanisms linking the filing of lawsuits to negative attitudes, it is difficult to speculate whether other types of lawsuits present the same backlash risks as tort suits. At the same time, as seen in Scalia’s dissent in Windsor and Kendall’s warnings in its aftermath, judges and activists share concerns about the political risks of other types of litigation. Moreover, earlier venue effects studies were conducted when the Supreme Court enjoyed high approval ratings. The risk of negative venue effects seems higher given the Court’s falling public support and growing negative media coverage (Grove Reference Grove2019). Under these circumstances, it is worth further exploring when litigation at the federal and state level produces negative attitudes toward claimants, rights, and courts as well as what can be done to reduce the risk of backlash against meritorious claims.

Conclusion

Institutional choice is central to the American fragmented policymaking process. To build on the venue effects literature, we examined attitudes toward claimants under U.S. injury compensation policy, which provides an array of options, including filing lawsuits or claims with government programs. We used the dispute tree to design a survey experiment to probe opinions of different types of claimants. This novel application of the dispute tree allowed us to randomize the choice of remedy and thus account for other factors that might shape attitudes toward claimants and explore the counterfactual of what would happen without litigation.

We find the choice of remedy matters. People have significantly more negative views of injury victims who litigate, even when they believe that the victim is injured, not at fault, and should not “lump it.” A secondary analysis suggested that explaining litigation was used as a last resort can significantly improve attitudes toward its justifiability. These findings add to the mosaic of diverse studies on venue effects, backlash, and perceptions of the legitimacy of ordinary litigation as well as point toward further research on managing the risks of opinion backlash. Along the way, we hope to encourage further use of survey experiments to explore the consequences of institutional choice and turning to the courts in layered policymaking systems both in the United States and abroad.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and editor at the Journal of Law and Courts for their thoughtful comments, as well as panel participants at the 2020 meeting of the Law and Society Association, including Anne Bloom, Lachlan Caunt, Takayuki Li, and Shozo Ota. We also thank the participants at the 2021 Experiments and Elites Conference at the University of Southern California, and particularly Neil Chaturvedi, Ann Crigler, Christian Grose, and Nicholas Weller for their keen insights at various stages of this project. Of course, any remaining errors are entirely our own.

Financial support

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation (Award No. 53-4871-1701) for its support of our ongoing project on the impacts of court-based policymaking.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results are available in the JLC Dataverse.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2023.9.