Introduction

William A. Whitaker and I described our experiments with machine translation of the Latin language, using our ‘Blitz Latin’ machine translator, in an article published in JACT Review (Whitaker and White, Reference Whitaker and White2002). This attracted much useful feedback from readers. Sadly, Dr Whitaker died in December 2010 and therefore he has been unable to contribute to this update concerning Blitz Latin.

The original article outlined the technical difficulties of constructing a machine translator for Latin to English, and concluded that the central difficulty was the ambiguity of the overloaded Latin language (‘overloaded’ being defined as too many unrelated meanings for many words), the multiplicity of overlapping inflections for the words, and the difficulty of assigning English word order to a sentence composed of words ordered by their writer according to their emphasis. The article gave several examples to illustrate the problem of Latin ambiguity. For the convenience of the reader some are repeated below, supplemented with other examples:

plaga: unrelated classical meanings of trap, curtain, region, blow. Further medieval meaning is plectrum-stroke.

domino: to the lord, from the lord, with the lord, by the lord.

gratia Domini Iesu: the grace of the Lord Jesus.Or with gratitude of the Lord to Jesus.

rex amat reginam: the king loves the queen. [Emphasis that it is the king who loves.]

reginam amat rex: the king loves the queen. [Emphasis that it is the queen who is loved.]

regem regina amat: the queen loves the king. Or he loves the king with the queen.

amas reges: you love the kings. Or you will rule the buckets.

amas mensas: you love the tables. Or the buckets measured.

rex est contentus: the king is/eats content (adj.). Or the king has been hastened/held/stretched.

nulla impudica Lucretiae exemplo vivet: no one unchaste from Lucretia will live by the example. Or no one unchaste will live by the example of Lucretia.

rex amat canem suum, qui habitat in stabulo. os mandit: the king loves his dog, which/who lives in a kennel. Chews a bone. [Is it the king or the dog that chews the bone? And os more commonly means ‘mouth’, not ‘bone’.]

Blitz Latin translates only from Latin to English, which permits the use of dedicated translation algorithms specific to Latin. It is a ‘sentence-based’ translator. That is, it creates its output by translation of complete sentences in isolation. The difficulties of passing information from one sentence to another were explained in the original article; the expert view that the subject of an earlier sentence is copied across to its successors was demonstrably not true unless by chance. We concluded also in our earlier article that a machine translator for Latin must have a sufficiently large dictionary. The reason was not the obvious one – that a word not found in the dictionary could not be translated – but rather that an unrelated Latin word might have a similar inflection that could substitute for the correct stem and the correct inflection. Thus, if the Latin noun rex, regis (king) were not present in the electronic dictionary, the short phrase amas reges (see above) could be translated only (and wrongly) as ‘you will rule the buckets’. This error turns a noun reges into the similar and unintended verb, providing a worse translation than if reges had been flagged as ‘unknown’.

A remark made by one of the readers of our first article was intended, and proved, to be particularly reassuring. Many ancient Latin texts, the reader informed us, had been preserved precisely because of their grammatical complexity and ingenuity. This has indeed proved to be the case. Texts written by medieval and later writers of Latin are, generally, much easier to read than those of the preserved ancient writers. It seems that, whereas today we play word-games in the form of crossword puzzles, the early Romans preferred to amuse one another by writing sentences of bizarre complexity for the reader to unravel. We know now that texts intended to instruct (e.g. Caesar, describing his wars, Vitruvius, with architecture, Celsus, concerning medicine) are much easier to translate than works such as those of Hyginus, describing his own fanciful ideas concerning astronomy (or rather, astrology). Latin poets, constrained by the need to select and arrange words in correct order to fit their metre, are also necessarily difficult to translate.

The ‘ablative absolute’ construction provides an interesting point of contention in the design of a machine translator for Latin. One or more Latin words containing the ablative case are used adverbially. Collins' Latin-English dictionary (1997) gives a number of examples including:

hostibus victis: ‘after beating the enemy, having defeated the enemy’ (literally ‘with the enemy beaten’).

exigua parte reliqua [aestatis]: ‘although only a little remained [of the summer]’ (literally ‘with small part remained [of the summer]’).

The failure of Blitz Latin to make adverbial translations in similar clauses has caused criticism from some users in the past, with the result that I examined a large range of clauses designated as ‘ablative absolute’, taken from books of Latin grammar and from the Internet. Yet what exactly is the problem? The literal translations seem to me to be perfectly simple to understand, and I have challenged any critics to provide examples where an adverbial translation would be understood easily whereas the literal translation would not. So far, no one has taken up the challenge.

Progress since 2002

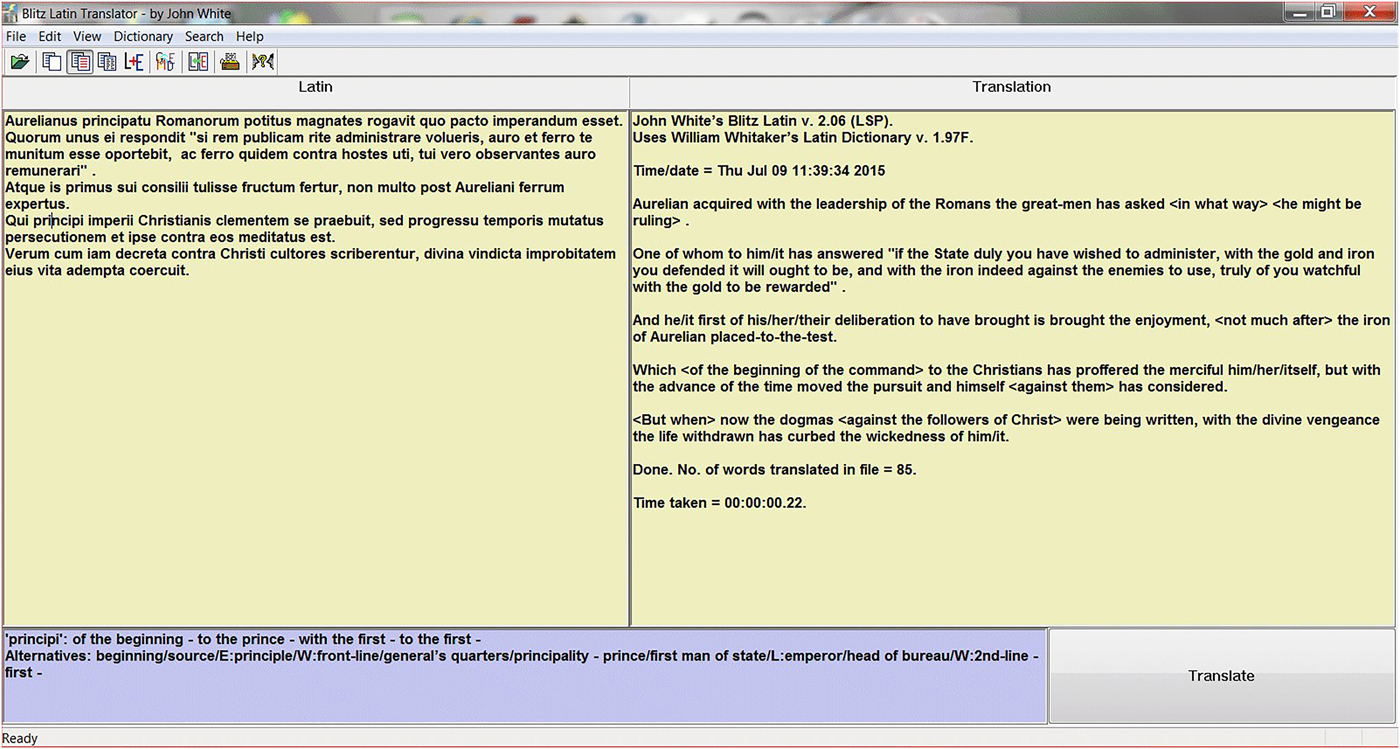

Some of the improvements to Blitz Latin have been cosmetic. The original display was fixed for the most common screen size used in 2001, but by 2003 it had become necessary to create a display that the user could resize to fit varying sizes of screen. This took a considerable effort, but it has not been necessary to alter it subsequently, even in these days of wide-screen computers. The screen layout has also remained the same. For some reason, contemporary machine translators of all languages preferred to have the language in the top half of the display and the translation in the lower half. This was difficult to read and unnatural: newspapers lay out their columns side-by-side and the well-known Loeb series of Latin-English texts has the Latin on the left page and the translation on the right. So this has been the method adopted from the outset by Blitz Latin. It is also the common method now employed by other machine translators, although whether this was due to our innovation, or was discovered independently, I cannot say. The right-hand translation window can be set to show the Latin translation only (as in the picture below) or both Latin sentences and their translation in alternating sentences. A third small window across the bottom of the screen provides output whenever the user left-clicks on a single Latin word on the left screen. The output for the third window can be switched between a list of alternative English meanings or the Latin syntax for the clicked word.

Blitz Latin main screen. On the left the Latin text, on the right the translation. In the bottom pane, result of left mouse-click on the Latin word principi. The words enclosed between ‘< >’ are Latin Standard Phrases, see main text.

Blitz Latin has always been engineered to provide a very fast translation, which encourages the user to make full use of its facilities. By 2004, the most critical search routine for Latin stems had been completely coded in ‘Assembly’, the processor's native machine language, which resulted in a speeding-up of some 12% by itself, while pre-storage of some of the most commonly encountered Latin words also provided another 15% improvement in speed. However, by 2005 it had become clear that there was a benefit to increasing the complexity of some of the translation routines. These new, complex, slower routines actually caused an increase in the overall speed of Blitz Latin, the reason being that each translation of a sentence has always been examined for self-consistency. To take a trivial example, a sentence such as rex amat bellum (the king loves war), deemed at first to have two subject nouns (rex, bellum), a 3rd-person transitive verb and no object, would be rejected, with advice to the Artificial Intelligence routines to find an object noun (bellum). The result of too many rejections was to slow up the translation, so that improvement of the selection routines for ambiguous words had the beneficial effect of reducing the number of re-examinations of the Latin sentence.

A startling improvement in translation quality occurred when Blitz Latin began to examine clauses, instead of an entire sentence. We tightened the definition of a clause further and further, so that clauses today are separated not only by any type of punctuation (including quotation marks) but even by conjunctions such as et (‘and’) and the various forms of the pronoun quis (‘who’ or ‘which’). Relevant information is transferred between clauses.

The English word ‘not’ is now placed in the translated sentence better than in early versions of Blitz Latin, although this proved to be unexpectedly difficult to achieve. For many years, Blitz Latin would translate a phrase such as scriptores non consentiunt as ‘the writers agree not’, providing a quaint old-English feel to the result. Today, the translation is ‘the writers do not agree.’

The ambiguity of Latin remains a big challenge. This ambiguity is less apparent to human translators, who can use their own general knowledge to separate many alternative meanings. Wrong translations ‘make no sense’. However, a machine translator has no concept of sense, common or otherwise. Blitz Latin has always offered users an editing option, so that they can apply their own common sense to the screen translation after Blitz Latin has made its decisions.

Throughout the 13 years that have elapsed since our paper in the old JACT Review, the pursuit of methods to reduce ambiguity has remained this writer's prime obsession. One option, first mooted in the earlier paper, was to introduce a ‘neural network’ for a handful of very ambiguous Latin words, such as plaga (see earlier) and saltus (leap, step, narrow passage, woodland). The principle behind a neural network is to ‘train’ a sample set (typically less than 10 per cent) of the total large group of apparently random data for a single Latin word, in an attempt to find non-obvious patterns in the surrounding Latin words of the sentence. The training set has its Latin meanings assigned correctly by a human (myself), and the patterns that result are used to allocate meanings for every instance of the same Latin word when encountered in any other Latin sentence.

The effort to create a neural network for a single Latin word is considerable, since naturally it is more useful to train a common ambiguous Latin word than to train a rare ambiguous word. Just five words (plaga, saltus, liber, lustrum, contentus) were selected for the training, and to discover whether the technique was effective in providing correct translations according to context. The result was an improvement over the original unvarying translation for each word, where the most frequently cited meaning had always been used. For example, plaga was always translated as ‘blow’; now other meanings are encountered. Even so, the reassignments of meanings are not always correct, and therefore this limited gain in reducing the ambiguity of Latin words has deterred further investigation into the neural network. Another deterrent was the knowledge that the patterns we had found for these five test words were extracted from our contemporary test set of some 3,000 Latin texts, and might have been different if extracted from (or applied to) a different test set of Latin texts.

A much easier line of attack has been simply to extend the electronic dictionary. In 2002, Blitz Latin contained some 34,000 Latin words as they would be counted in a paper dictionary, of which around 4,000 were ‘medieval’ words (i.e., first introduced into Latin during the medieval period). In 2015, Blitz Latin has around 58,000 words – more than 3,240,000 words if we count each inflected variant as a separate word – including much enhanced dictionaries for the medieval age, for the modern era, for the ‘Vatican era’ (i.e., derived from Vatican texts) and a new, optional, botanical dictionary for those who wish to translate botanical publications written in Latin. The official language for botanical research was Latin until 2013; since then, the official language has been English. It was certainly an unfortunate coincidence that the botanical Latin supplement for Blitz Latin was also first published in 2013. However, there remains a vast body of botanical Latin which would be inaccessible for novices without the aid of a translator like Blitz Latin.

In 2002, we could claim that Blitz Latin would translate all Latin words, in our then test set of some 3,000 Latin texts, which occurred more than 20 times (excluding proper names, foreign words and misspellings). In 2015 I can claim that Blitz Latin will translate all Latin words that occur more than four times in the current 4,000 Latin test texts. The great majority of words that occur fewer than four times will also be found in Blitz Latin's electronic dictionary. We have a large dictionary!

Another useful method to improve the translation of Latin texts has been to examine each line of Blitz Latin's output by hand, and to try to discover why any individual translation has gone awry. The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) offers a CD-ROM that contains every Latin text known up to 200 AD, and a few others besides (for example, the Augustan Histories and Justinian's legal digest.) These texts have been proof-read by two sets of external experts, and thus represent a very important primary source of Latin texts, as passed down to modern times by medieval copyists. For years now, I have studied translations by Blitz Latin of short extracts from every one of the entire range of PHI texts. This procedure has uncovered many, very rare, classical words for the electronic dictionary, but the real purpose is to examine exactly why some translations have failed. Frequently the reason is trivial. An ambiguous word has two or more unrelated meanings, and, in the absence of any defining grammatical feature, Blitz Latin has in this case wrongly used the meaning cited in our electronic dictionary as most frequent. There is very little that can be done to fix this kind of error, except to alter the weightings of frequencies for meanings in the electronic dictionary when an alleged minor meaning proves to occur far more often than expected.

Sometimes a simple program bug is discovered, and can be fixed. Blitz Latin is subject to a policy of constant improvement, and it happens occasionally that an ‘improvement’ is defective itself, or else falsifies the output from earlier code. However, the happiest outcome results – occasionally – when a handful of similar mistranslations occurs over many texts, and visual examination provides a common factor that can be corrected with a code algorithm. That is always very satisfying, almost always unexpected and usually could not have been predicted in advance.

This relentless examination and re-examination of real Latin texts has had the long-term results that:

-

i) Defects in Blitz Latin's translations, excepting those caused by ambiguity, are now rare.

-

ii) Blitz Latin is exceptionally stable in use, and releases of new versions are subjected to extended soak-testing. This includes an artificial electronic mimicry of the effect of the user left-clicking (to provide full English meaning) on every Latin word in our current set of 4,000 Latin text files.

Misspelling

The poor spelling of medieval writers, lacking access to dictionaries, and often spelling-as-they-spoke, had resulted by 2002 in the coding of a phonetics search in the Blitz Latin electronic dictionary. This works quite well, and is still used in Blitz Latin's latest versions, but does not discover all medieval misspellings of classical Latin words. It is also possible to create an additional medieval phonetic variant of our main electronic dictionary, as an alternative to the coded approach. I experimented with the phonetic dictionary, an optional file named ‘phoneticUK.dat’, as an alternative to the coded search of the main dictionary. It proved to be very difficult to choose between the alternatives: on some test medieval texts, the coded approach discovered and corrected more misspellings, or was quicker for locating misspellings common to both the coded and the file alternatives; with other medieval files the situation was reversed. I took the decision finally to retain the coded phonetics search on the prosaic ground that it required a smaller package to be installed on the user's computer. However, the phonetic file is still generated automatically every time that the main electronic dictionary is compiled, and could be easily re-introduced at once if ever I change my mind about the better method for phonetics search.

Simple ‘slurs’ in spelling, such as the frequent medieval substitution of an initial imm- with inm-, have been resolved with code in Blitz Latin from the earliest days.

The users of Blitz Latin

When first we created the commercial version of Blitz Latin, we anticipated that the great majority of users would fall into two categories:

-

i) students (and perhaps their teachers);

-

ii) Latin academics who required essentially only the huge vocabulary and phonetic ability of Blitz Latin.

We were largely wrong with both predictions. Initially there was indeed a significant minority of users of Blitz Latin in the form of students studying Latin, mostly at high school. To accommodate such students, we added ‘Easy Latin’ as an option to Blitz Latin in 2006. This option ensured that all ambiguous Latin words in the text would be translated as their most common form only, reflecting such basic usage in school teaching and related examination papers. However, the students have now turned predominantly to (free) Google Latin. As we shall see below, the latter has the potential to provide excellent professional translations of standard, idiosyncratic Latin texts (such as the poets and Cicero). The translations derive ultimately from human experts in Latin, and one wonders what the students' teachers make of this kind of non-literal output. My Latin teacher forbade absolutely any use of professional translations for class work, on the grounds that the translations were not literal and therefore unacceptable.

Secondly, Latin academics feel that they do not need any help whatsoever from a machine translator. This is a pity, since their students will make many of the same errors as the translator.

However, it appears that many academic staff working on medieval studies (for example, in history, medicine, law, ecclesiastical studies) have proved to be enthusiastic users of Blitz Latin, perhaps because their institutions lack a Latin department, and, interestingly, the majority have received at least some instruction in Latin at school, often in further education. Such users form an ideal symbiotic relationship with the developers of Blitz Latin, and we have learned a great deal from their feedback. Equally, of course, we have been able to adapt and enhance the electronic dictionary and to introduce better code in response to their requests. An example is the addition of a series of commands (cut/copy/paste) made available when right-clicking on a word, after a request by an American user.

Since most of our users wish to translate medieval Latin, I have made a massive effort to improve translations in this area. I have enhanced the phonetics code, and adapted Blitz Latin's word-ordering routines to suit this important group. Blitz Latin has always offered to the user two methods for word-ordering. ‘SVOE’ (subject-verb-object-else) word ordering is required generally when reordering phrases derived from classical Latin. ‘Nom-V’ (nominative, then verb) is recommended for translations from medieval Latin or later. Many of the users of Blitz Latin had discovered independently the superiority of Nom-V for medieval texts, and communicated their findings to us. All users can choose which Latin period (classical, medieval, modern) to adopt, and which word-ordering system – including no word ordering at all – that they prefer.

Blitz Latin has always been developed for Microsoft's Windows™ operating system, but there have been some users who have managed to use the translator successfully with Apple's Mac™ computers with the aid of a third-party emulator (from Apple's iOS™ operating system to Windows). The most successful of these convertors appears from feedback to be the ‘Wine’ emulator, which can be downloaded free from Wine's website.Footnote 1 The author, who lacks a Mac computer, and therefore cannot install Blitz Latin on such a computer, can neither test nor endorse these claims, nor provide back-up in the event of any problems.

Quality of Translation

The English language, like other ‘rich’ European languages including the Romance languages derived from Latin, assigns precise meanings to its words. The classical Latin language, however, dealt in concepts. The language lacks the definite and indefinite articles (respectively ‘the’ and ‘a’), and a simple Latin word such as rex, usually defined in dictionaries as ‘king’, has the real conceptual meaning of ‘male regal personage’. The well-known word imperator (conceptually ‘he who gives orders’) is particularly troublesome, since it can be assigned to a successful general, to the emperor himself, or to the head of a four-man road-repair gang. This ambiguity spread into medieval times. Niermeyer's famous medieval Latin dictionary devotes five pages (in three modern languages) to the medieval concept of lex, usually described in any basic Latin dictionary as ‘law’.

Thus there exists no precise mechanism by which Latin can be translated accurately into English, or other rich modern language. The translator must provide a certain amount of infill, and it is instructive to note the number of modern translations into English that exist, for example, for Vergil or Cicero. There can be no single, accurate translation.

A machine translator, such as Blitz Latin, can follow only such rules as have been programmed into it. This makes for a very stilted, literal translation into English, and it is difficult to see how this can be improved with current technology for machine translation. However, there exist two alternative routes. One is unique to Blitz Latin in its complex implementation for Latin. We refer to this technique as ‘Latin Standard Phrases’ and it will be discussed below.

The second alternative is also used widely for translations between modern languages, where the machine translator is commonly described as a ‘statistical translator’.Footnote 2 I prefer the title ‘jigsaw translator’, which is far more descriptive.

The principle of a jigsaw translator is that many existing translations by human professionals of foreign text into English are chopped into small, electronic jigsaw pieces, where (metaphorically) a few words of the foreign language can be found on one side of the jigsaw piece, and their professional translation is found on the other. The size of the pieces can vary from one word to many. When the user translates a new text with a jigsaw translator, the new text is also chopped into pieces, which are matched with the existing set of pieces, and the translation of the latter is used for that piece of text. Naturally, larger jigsaw pieces (many words) are preferred, since they are more likely to be consistently accurate; naturally, such large pieces are encountered rarely in user texts. The chopping technique is completely automated, and the jigsaw translator lacks any knowledge of such basics as grammar or even vocabulary, except insofar that a jigsaw piece contains a word identical to that which it is trying to match. Different human translators will sometimes interpret the same small piece of foreign text in different ways – particularly if one of the words has more than one meaning – and therefore the most commonly encountered translation is used for that piece. Hence the title ‘statistical translator’. This technique works surprisingly well between modern ‘rich’ languages, for example between modern Italian and English, since the word orders are generally the same and there is little ambiguity.

Can a jigsaw translator be effective with Latin, with its erratic word order, its ambiguity for many word meanings, and the range of inflections found on the end of most Latin words? The short answer would appear to be no, although it depends very much on the text. As mentioned previously, the Latin poets were constrained by their need to comply with their metre, and therefore wrote Latin texts that were essentially unique in word order and choice of words throughout. Thus a jigsaw translator that includes, for example, Vergil's Aeneid as part of its jigsaw pieces can be expected to be exceedingly effective at translating Vergil's Aeneid when presented. It will be simply regurgitating the original human professional's translation into English. Indeed, this is a distinguishing characteristic, or diagnostic, of jigsaw translators – they can translate some poetry nearly perfectly, despite the well-known difficulty of machine translation of poetry. I can barely understand poetry written in my own language – the likelihood that I could program a machine to translate foreign poetry perfectly into English is negligible. Yet jigsaw translators sometimes produce perfect results. They are regurgitating someone else's work.

However, any attempt to translate, let us say, a rare medieval Latin text by a jigsaw translator is likely to be crippled by its lack of vocabulary (or the correct inflections on words encountered) and inappropriate jigsaw pieces, designed for use with other texts. Another serious problem, caused by medieval misspelling of classical Latin words, is that some jigsaw pieces stored by the jigsaw translator will be in classical spelling, and thus unable to match the user's medieval text, while some other jigsaw pieces will be in medieval (mis)spelling and unable to match the classical spelling found in classical, medieval and modern texts.

There is also the problem of faulty creation of the texts on the jigsaw pieces. To take a hypothetical example, the sentence rex amat non reginam (the king does not love the queen) might be divided inaccurately into two jigsaw pieces: rex amat = the king does not love and non reginam = the queen, so that if the user has a text for translation that includes the words rex amat mensam, the (false) translation will be ‘the king does not love the table.’ I have seen actual examples of this kind of significant error in more complex texts. Cutting up jigsaw pieces requires great skill and care, but in practice is always automated according to rules.

These observations are borne out in practice with ‘Google™ Latin’, part of Google's very large range of jigsaw translators. Its defects of translation from Latin into English are in part obscured by the very high standard of its English phraseology (regardless of accuracy) and the happy chance that translations into English do not require attention to putting the correct inflection onto the end of every English noun, adjective and verb. Often, though, its translations bear little relationship to the Latin input. Google Latin's weaknesses are exposed mercilessly when one attempts to translate a single clause from English to Latin, a procedure that uses a reversal of the same jigsaw pieces provided for translation from Latin to English. If we invent any short clause (subject, verb, object), throw in a few improbable adjectives to qualify nouns, and examine the Latin phrase that results, we find that the word order usually follows the English order and the inflections are only correct by chance (which is to say, rarely).

Latin Standard Phrases

I believe that the only route currently viable for the accurate machine translation of Latin into English is a line-based grammatical translator, rather than a jigsaw translator. This gives the better chance of resolving difficulties caused by ambiguity and by word order based on emphasis. A paragraph-translator would doubtless be better still, and indeed Blitz Latin does retain certain types of information between sentences and even between paragraphs. Nevertheless, most of Blitz Latin's translation is based on information specific to its current sentence.

I am painfully conscious of the appearance of the stiff and sometimes peculiar form of English translation provided by Blitz Latin's literal-minded algorithms. Blitz Latin has provided from 2004 a special text file ‘userphrases.txt’ that could be augmented by the user in order to provide fixed translations of short phrases. We provided a few examples as encouragement in the text file, for example mihi subolet = ‘I detect’ (literally ‘to me it makes a weak scent.’) The maximum number of such phrases was limited to 100, owing to the heavy computing demand of examining each of the short phrases for every Latin word encountered in a Latin text.

There is nothing new about this idea, which has been implemented in machine translators generally almost from their first introduction. Standard paper Latin dictionaries provide many examples of these special phrases, including that given above. We call these examples ‘Latin Standard Phrases’ (LSPs), and their utility is greatly reduced in Latin by the need to consider inflections on most Latin words.

The big breakthrough for Blitz Latin came with the discovery that it was possible to create efficient code that would conjugate the infinitive form of any verb within a given LSP. To take an example from the current list of LSPs, amare te – ‘to love you’. The new code will convert this basic form into any of the 180-odd verb variants of the verb amare. For example amavi te – ‘I have loved you.’ Suddenly, we have a very valuable method for improving the translation into English of any difficult clause that contains a verb.

First introduced into the new Blitz Latin version 2 in late 2013, the number of LSPs has been increased in leaps and bounds to more than 12,000 entries by 2015. The LSPs have been derived from standard Latin dictionaries (covering all ages from classical to modern Latin), from user feedback and from the author's constant examination of Blitz Latin's translations of the PHI texts mentioned previously. Meissner's list of Latin clauses (Meissner, Reference Meissner and Meissner2012) has also been of considerable value.

In particular, the extra time required for a search of the LSPs has been reduced from the original overhead of 15% beyond the original translation time without the LSPs, to an overhead of about 1%. For theoretical reasons derived from the coding, this overhead for 12,000 LSPs should increase only slightly for every doubling of the number of LSPs.

The addition of these LSPs when encountered in Latin text has improved markedly the quality of translations by Blitz Latin. The biggest weakness lies with the number of sentences translated without any LSP being encountered at all. Frequently, no LSP was required anyway; the original translation was sufficiently good. Nevertheless, the effect of word order on these LSPs remains a challenge, resulting in a certain amount of duplication. For example, we may need as LSPs both amare te and te amare. Fortunately, as stated above, such duplication has only a marginal effect on the speed of translation by the aptly-named Blitz Latin.

It is necessary to clarify the big difference between the translations of a line-based translator with LSPs, and a jigsaw translator. The former assigns the grammar as correctly as it can to ambiguous Latin text, after first correcting medieval or other misspellings, and with very limited word reordering at this point. Then it applies the Latin Standard Phrases (where available) and reorders the resulting text. By contrast, the jigsaw translator decodes Latin text with matching pieces of a human professional's loose (non-literal) translation of a different text.

Conclusions

Blitz Latin is a unique machine translator for Latin into English. Academic attempts at the creation of similar translators have fallen by the wayside (I do not know of any Latin translator currently being developed in an academic environment), while occasional commercial alternatives have either disappeared or are not being developed further. The market for Latin translation is simply too small for the economic deployment by the large translation houses of experts with skills in Latin, artificial intelligence and professional coding. The jigsaw route to translation of Latin, which uses essentially a mincing machine to chop up professionally translated texts, exemplified by Google Latin, is (I believe) inappropriate for a language with ambiguity of meanings and inflections, and with essentially random word order.

Blitz Latin is subject to a policy of continuous improvement, with upgrades typically every six months. Upgrades are free to existing users. A demonstration version can be downloaded free from the international distributors (British-based Software-Partners, www.blitzlatin.com). The free version has a limited medieval vocabulary and around 45 Latin Standard Phrases only, for demonstration purposes. The commercial version requires purchase of a licence, and adds a 4,000-word medieval Latin dictionary and (currently) more than 12,500 LSPs.