Introduction

Pregnancy termination is a serious public health issue with far-reaching consequences (WHO, 2020). Every year, approximately 56 million abortion cases are recorded, with legal abortion contributing to about 34 million cases across the globe (WHO, 2020). Pregnancy termination is often used interchangeably with induced abortion. Moreover, about 97% of all unsafe abortions occur in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs), of which Papua New Guinea (PNG) is included (Lisa et al., Reference Vallely, Homiehombo, Kelly-Hanku and Whittaker2015). Pregnancy termination can have dire consequences on women’s health (e.g. haemorrhage, sepsis, and uterine perforation) and eventually death (WHO, 2012). Evidence from the literature shows that about 13% of global maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortion (Khatri, Poudel & Ghimire, Reference Khatri, Poudel and Ghimire2019). It is therefore important to ascertain the factors contributing to pregnancy termination, particularly unsafe abortions, including intimate partner violence (IPV).

IPV includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and controlling behaviours by an intimate partner (Ahinkorah, Reference Ahinkorah2021; Kabir et al., Reference Kabir, Rahman, Monte-Serrat and Arafat2017; Upadhyay et al., Reference Upadhyay, Gipson, Withers, Lewis, Ciaraldi, Fraser, Huchko and Prata2014). Recently, IPV issues have become important in national development globally (Kabir & Khan, Reference Kabir and Khan2019). IPV has been associated with numerous consequences for women, including pregnancy loss through miscarriages and stillbirth (Durevall & Lindskog, Reference Durevall and Lindskog2015) and termination of pregnancies through induced abortion because of post-traumatic stress disorder and psychological distress (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Padilla, Villaveces, Patel, Atuchukwu, Onotu and Kancheya2019). Despite the attention given to addressing IPV, its prevalence is continuously high in LMICs, including PNG. There have been reported high rates of domestic violence and rape cases in PNG (Government of PNG et al., 2013; Kelly-Hanku, Reference Kelly-Hanku2013; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Bleakley and Ola2011). It is also important to note that IPV against women can happen at any phase of a woman’s life, including during pregnancy. It is possible to argue that complex and deeply nested sociocultural and economic mechanisms serve to promote and perpetuate the act in various socio-spatial situations, given that the prevalence of IPV differs significantly by geography (Adu et al., Reference Adu, Asare and Agyemang-Duah2022). From an ecological perspective, individual, family, and community elements levels are critical in determining how much IPV is exposed to (Adu et al., Reference Adu, Asare and Agyemang-Duah2022).

Relating to the individual-level factors, previous studies showed personal historical and behavioural factors such as alcohol abuse, young age, low level of education, childhood exposure to IPV, unemployment, and marrying before 18 years as risk factors for IPV (Sabri et al., Reference Sabri, Renner and Stockman2014). Family- and community-level influences are profoundly ingrained in cultural mores, beliefs, and customs, which have acted to maintain gender inequities that frequently discriminate against women on a sexual, physical, and emotional level (Bonomi et al., Reference Bonomi, Trabert, Anderson, Kernic and Holt2014). Evidence from the literature has shown that IPV has adverse effects on the reproductive, psychological, and physical health of the victims (Pallitto et al., Reference Pallitto, García-Moreno, Jansen, Heise, Ellsberg and Watts2013; Salazar & San Sebastian, Reference Salazar and San Sebastian2014). It has been reported in Tanzania that IPV has been linked to higher odds of unintended pregnancies that result in pregnancy termination (Stöckl et al., Reference Stöckl, Filippi and Watts2012). Previous studies conducted in Angola (Yaya, Kunnuji & Bishwajit, Reference Yaya, Kunnuji and Bishwajit2019), Nigeria (Benebo, Schumann & Vaezghasemi, Reference Benebo, Schumann and Vaezghasemi2018; Oluwole, Onwumelu & Okafor, Reference Oluwole, Onwumelu and Okafor2020; Onukwugha et al., Reference Onukwugha, Magadi, Sarki and Smith2020), Ghana and Mozambique (Dickson, Adde & Ahinkorah, Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018; Ogum Alangea et al., Reference Ogum Alangea, Addo-Lartey, Sikweyiya, Chirwa, Coker-Appiah, Jewkes and Adanu2018) have investigated the prevalence of termination of pregnancy and IPV from the diverse contextual backgrounds. However, to the best of our knowledge, no known study had examined the association between the termination of pregnancy and IPV among women in PNG despite the high prevalence of these experiences.

Hence, we investigated the relationship between IPV and pregnancy termination in PNG. Today, the sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing) and SDG 5 (gender equality), are committed to fostering good maternal health and addressing IPV, respectively. Therefore, we envision that the findings from our study will contribute to informing interventions aimed at attaining SDGs in PNG.

Methods

Data source, sampling technique, and sample size

The study used data from the 2016–2018 PNG Demography and Health Survey (PNGDHS) conducted from October 2016 to December 2018. This survey is the first demographic and health survey conducted in PNG. The PNGDHS aimed to generate comprehensive data on demographic, maternal, and reproductive issues such as fertility, family planning awareness and practices, breastfeeding practices, health behaviours, immunisations, and domestic and IPV. Through the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme, technical support for the execution of the survey was provided by Inner City Fund (ICF), with the financial support of the PNG Government, the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and UNICEF (NSO & ICF, 2019). The sample for the 2016–2018 PNGDHS was nationally representative and covered the entire population that lived in private dwelling units in the country. The survey used the list of census units (CUs) from the 2011 PNG National Population and Housing Census as the sampling frame and adopted a probability-based sampling approach. Specifically, a two-stage stratified cluster sampling procedure was followed. The methodology and selection procedure details have been reported in the PNGDHS final report.

Each province was stratified into urban and rural areas, yielding 43 sampling strata, except the National Capital District, which has no rural areas. The division paid particular attention to urban–rural variations. Samples of CUs were selected independently in each stratum in two stages. In the first stage, sorting the sampling frame within each sampling stratum to achieve implicit stratification and proportional allocation using a probability proportional-to-size selection was done. In the second sampling stage, a fixed number of 24 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing, resulting in a total sample size of approximately 19,200 households. To prevent bias, no replacements and no changes of the pre-selected households were allowed in the implementing stages. In cases where a CU had fewer than 24 households, all households were included in the sample. A total of 17,505 households were selected for the sample, of which 16,754 were occupied. Of the occupied households, 16,021 were successfully interviewed, yielding a response rate of 96%. In the interviewed households, 18,175 women aged 15–49 years were identified for individual interviews; interviews were completed with 15,198 women, yielding a response rate of 84%. In this present study, the sample comprised 9,943 women who were in intimate unions (either married or co-habiting) during the survey.

Study variables

Outcome variable

Pregnancy termination in the form of miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth was the outcome variable in this study. In the PNGDHS, pregnancy termination was defined as any pregnancy that resulted in a miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth (NSO & ICF, 2019). This definition has been used in most studies to reduce social desirability bias (Onukwugha et al., Reference Onukwugha, Magadi, Sarki and Smith2020; Samad et al., Reference Samad, Das, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Frimpong, Okyere, Hagan, Nabi and Hawlader2021; Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Amouzou, Uthman, Ekholuenetale, Bishwajit, Udenigwe and Shah2018; Antai, Reference Antai2012; Ibisomi & Odimegwu, Reference Ibisomi and Odimegwu2008). The definition is also appropriate in settings such as PNG, where the law prohibits induced pregnancy termination (Lisa et al., Reference Vallely, Homiehombo, Kelly-Hanku and Whittaker2015). Thus, in line with previous studies (Onukwugha et al., Reference Onukwugha, Magadi, Sarki and Smith2020; Samad et al., Reference Samad, Das, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Frimpong, Okyere, Hagan, Nabi and Hawlader2021; Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Amouzou, Uthman, Ekholuenetale, Bishwajit, Udenigwe and Shah2018; Antai, Reference Antai2012; Ibisomi & Odimegwu, Reference Ibisomi and Odimegwu2008), pregnancy termination was measured by a single item: ‘Ever had a terminated pregnancy?’ This question yielded a dichotomous response of ‘no’ (0) and ‘yes’ (1). The present study by using this broad measure of pregnancy termination did not differentiate between induced or spontaneous abortion, since both forms can be influenced by IPV (Bola, Reference Bola2016).

Predictor variable

The key explanatory variable in this study was women in union experience of IPV. We generated the explanatory variable based on three main variables, including physical, sexual, and emotional violence. These variables were derived from the optional domestic violence module, where questions are based on a modified version of the conflict tactics scale (Kishor, Reference Kishor2005; Straus, Reference Straus1979). The present study focused on the experience of physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the last 12 months preceding the survey. Six standard items, including whether the respondent’s last partner ever: pushed, shook, or threw something at her; slapped her; punched her with his fist or something harmful; kicked or dragged her; strangled or burnt her; threatened her with a knife, gun or other weapons; and twisted her arm or pulled her hair, were used to generate the experience of physical violence. Regarding sexual violence, three standard items, including whether the partner ever physically forced the respondent into unwanted sex; whether the partner ever forced her into other unwanted sexual acts; and whether the respondent has been physically forced to perform sexual acts she didn’t want to, were used to generate the experience of intimate partner sexual violence. On emotional violence, women in the union were asked if their last partner ever had threatened to harm her, insulted or made her feel bad. For each item, the responses were ‘never’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, and ‘yes, but not in the last 12 months. However, for our analysis purpose, we created a dichotomous variable to represent whether a respondent had experienced sexual violence in the past 12 months by coding never, yes, but not in the last 12 months together as ‘No’ (0) and yes, often and sometimes, coded together as ‘Yes’ (1). To obtain the overall experience of IPV, we created a third variable, known as experienced IPV in the last 12 months, to represent whether a respondent had reported experiencing either physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence in the past 12 months. The analysis was limited to the experience of IPV in the past 12 months to reduce the bias lifetime experience of IPV could bring since the focus of the study was to look at pregnancy termination within women in the union currently and that past year experience of IPV may have occurred within the current union (Ahinkorah, Reference Ahinkorah2021).

Confounding variables

Theoretically and empirically relevant demographic and socio-economic variables were included as confounders. These individual and contextual variables were included in the analysis based on their association with the outcome variable found by previous studies (Onukwugha et al., Reference Onukwugha, Magadi, Sarki and Smith2020; Samad et al., Reference Samad, Das, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Frimpong, Okyere, Hagan, Nabi and Hawlader2021; Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Amouzou, Uthman, Ekholuenetale, Bishwajit, Udenigwe and Shah2018; Bago, Hibslu & Woldema um, Reference Bago, Hibstu and Woldemariam2017; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Ahinkorah, Adu and Yaya2021) and their availability in the PNGDHS datasets. We included 12 socio-economic and demographic variables as confounders to adjust for the modelling. These variables included respondent’s age in years (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, and 45–49), place of residence (rural and urban), religion (Christian and non-Christian), highest educational level (no education, primary, secondary, and higher), marital status (married and co-habiting), partner’s age in years (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45+, and 55+), partner’s educational level (no education, primary, secondary, and higher), exposure to television (no and yes), exposure to the radio (no and yes), exposure to newspapers/magazines (no and yes), contraceptive use (no and yes), occupation (not working and professional/technical/managerial), and wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest).

Statistical analysis

Both descriptive (frequencies, percentages, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential (chi-square and binary logistic regression) analyses were done using STATA version 13. The statistical analysis followed some essential steps. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies were calculated to describe the demographic and other sample characteristics. We calculated the proportion of women who had experienced IPV in the last 12 months and those who had terminated pregnancy using prevalence odds ratios (OR). Pearson’s chi-square test examined the differences in pregnancy termination by IPV and socio-demographic characteristics. Both bivariate and multiple logistic regression were performed to model the association between IPV and pregnancy termination. We fitted four regression models to derive both unadjusted and adjusted effects of IPV on pregnancy termination. Model 1 included dependent and independent variables only; thus, it was the base model. While adjusting for the theoretically relevant confounding variables, Models 2, 3, and 4 introduced demographic, social, and economic factors to investigate whether these variables play any role and might tamper the effects of IPV on pregnancy termination. Before the regression analysis, diagnostics checks for multicollinearity were conducted using the variance inflation factor (VIF). In this analysis, none of the VIF scores exceeded the value of 2.38, suggesting no multicollinearity. All the estimates in this study are derived by applying appropriate sampling weights supplied by PNGDHS, 2016–2018, and the complex survey design to provide unbiased estimates for the OR and confidence intervals (CIs). We deleted all missing values from the analysis. The results of the regression analyses were presented as crude odds ratios (cOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) at 95% CIs. A statistical significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05 was selected.

Data availability and ethical consideration

The data have been archived in the public repository of DHS. Access to the data requires registration which is granted specifically for legitimate research purposes. Consent forms were administered at household and individual levels per Human Subject Protection. The dataset can be accessed at https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Papua-New-Guinea_Standard-DHS_2017.cfm?flag=0.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of women in the union in PNG

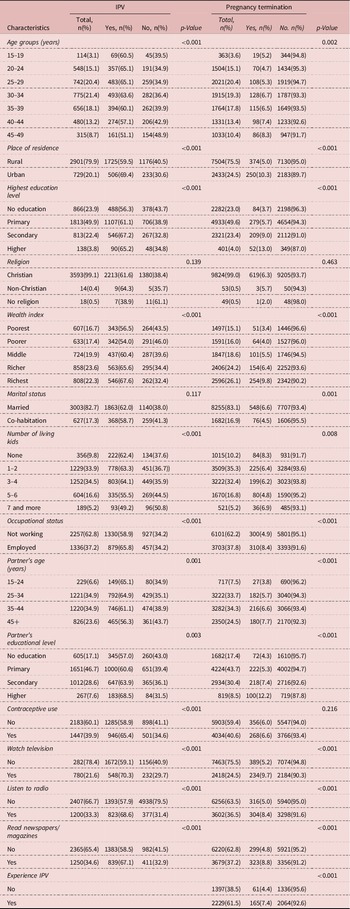

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants by pregnancy termination status are reported in Table 1. The results showed that 20.4% of the participants were aged 25–29 years, 75.5% resided in rural areas, 49.6% had a secondary education, 99.0% were Christians, and 26.1% classified themselves as richest based on the wealth index. The results further revealed that 83.1% of the participants were married, 35.3% were living with 1–2 children, 62.2% were not working, and 34.3% of the participants’ partners were aged 35–44 years. Also, 43.7% of the participants’ partners’ had a primary level of education, 40.6% of the participants used contraceptives, 24.5% watched television, 36.5% listened to the radio, and 37.2% read newspapers/magazines.In a chi-square analysis, the study revealed that there was a statistically significant relationship between age groups, place of residence, highest education level, wealth index, marital status, number of kids, occupational status, partner’s age, partner’s educational level, watching of television, listening to the radio, reading newspapers/magazines, and the experience of IPV concerning pregnancy termination status among women in the union in PNG.

Table 1. IPV and pregnancy termination status among women in union

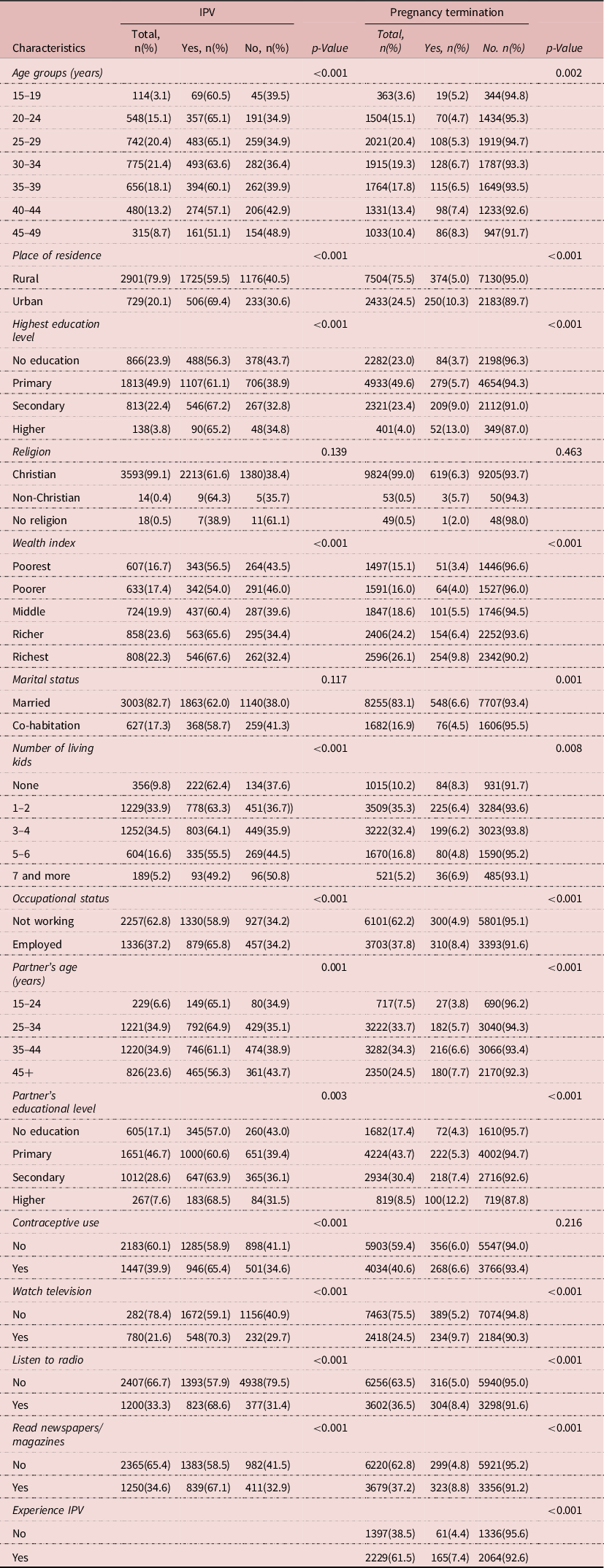

Prevalence of IPV and pregnancy termination

Table 2 presents results on the prevalence of experiences of IPV and pregnancy termination. Overall, 6.3% of women involved in this study had ever terminated a pregnancy, and 6 in 10 women (61.5%) reported having experienced IPV in the last 12 months preceding the survey. Specifically, 53.1%, 48.9%, and 26.9% of the women reported of physical, emotional, and sexual violence, respectively. Of those women who experienced IPV, 7.4% had ever terminated a pregnancy (see Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of IPV and pregnancy termination

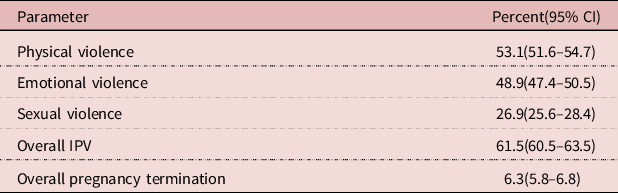

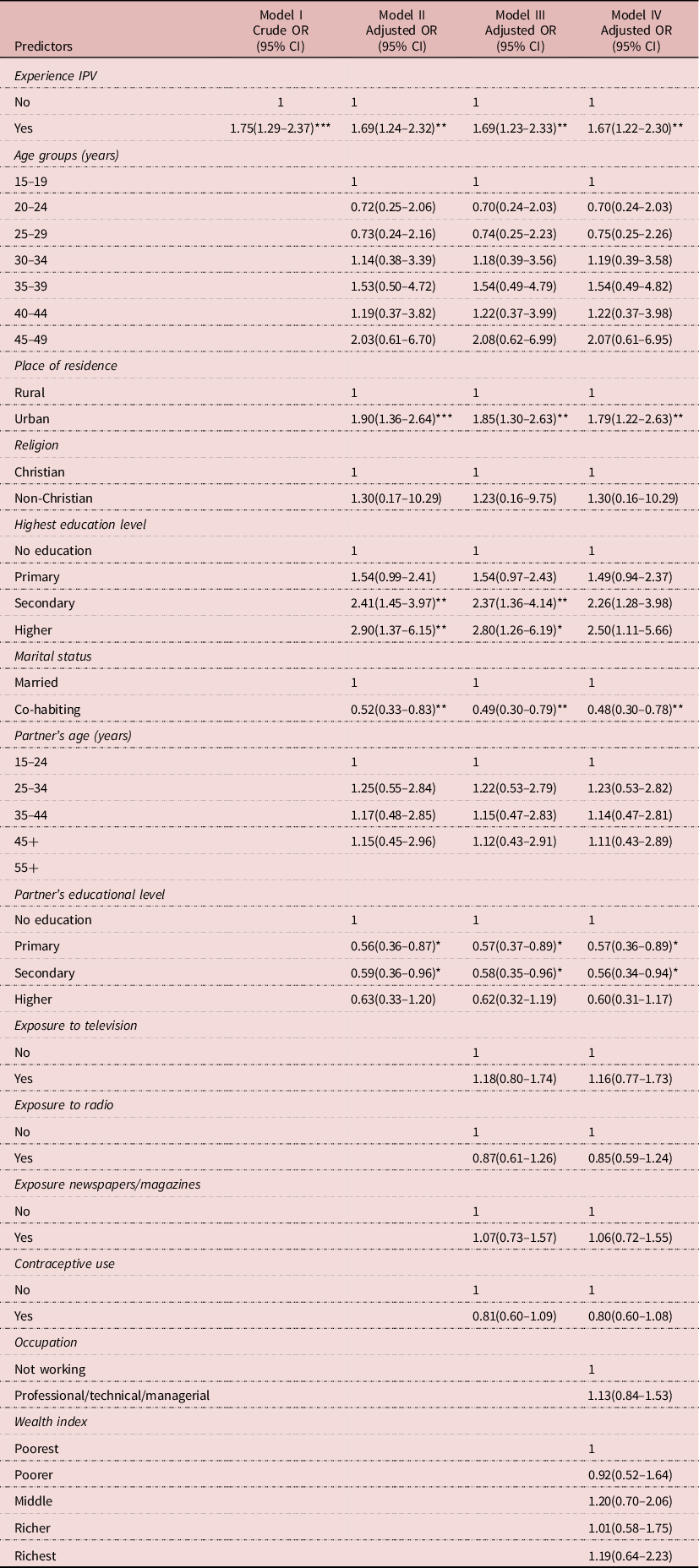

Association between IPV and pregnancy termination

Table 3 presents results on the association between IPV and pregnancy termination among women in the union in PNG. In Model 1, the study revealed that participants who had experienced IPV were 1.75 times significantly more likely to terminate a pregnancy than those who had not experienced IPV (cOR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.29–2.37). In Model 2, when demographic variables were added to the variable in Model 1, the study revealed that participants who were exposed to IPV (aOR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.24–2.32), those who resided in urban areas (aOR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.36–2.64), and those with higher education (aOR: 2.90, 95% CI: 1.37–6.15) were significantly more likely to terminate pregnancy compared with their counterparts. Again, it was found in Model II that participants who were co-habiting (aOR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.33–0.83) and those with a secondary level of education (aOR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.36–0.96) have significantly lower odds of terminating pregnancy compared to their counterparts. In Model III, when social variables were added to all variables in Model II, the study revealed that participants who were exposed to IPV (aOR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.23–2.33), those who resided in urban areas (aOR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.30-2.63), and those with higher education (aOR: 2.80, 95% CI: 1.26-6.19) have a significantly higher likelihood of terminating pregnancy compared with their counterparts. Besides, in Model III, the study revealed that participants who were co-habiting (aOR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30–0.79) and those whose partners have a secondary level of education (aOR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.35–0.96) have lower odds of terminating pregnancy compared with their counterparts. In Model IV, when economic variables were added to all variables in Model III, the study found that participants who were exposed to IPV (aOR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.22–2.30) and those from the urban areas (aOR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.22–2.63) were significantly more likely to terminate a pregnancy than their counterparts. Further, the study revealed that co-habiting participants (aOR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.30–0.78) and those whose partners had a primary level of education (aOR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.36–0.89) were significantly less likely to terminate pregnancy compared with their counterparts. One important take-home point as far as this study is concerned is that, throughout the stages of the model building, that is, from Model I through to Model IV (final model), IPV remains a strong driver of pregnancy termination among women in the union in PNG as the magnitude and direction of association persisted.

Table 3. Bivariate and Multivariable regression of the relationship between IPV with pregnancy termination

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Discussion

IPV is the most common form of gender-based violence, which includes all physical, sexual, or emotional harm as well as controlling behaviours aggravated by a former or current partner (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Ahinkorah, Adu and Yaya2021). This current study assessed the prevalence and association between IPV and pregnancy termination among women in PNG. Overall, the finding from our study revealed a 6.3% prevalence of pregnancy termination and a 61.5% prevalence of IPV among women in PNG. Our findings contradict results from related studies conducted in Bangladesh (Mosfequr, Reference Rahman2015), Nepal (Dalal, Wang & Svanstrom, Reference Dalal, Wang and Svanström2014), and Tanzania (Stockl et al., Reference Stöckl, Filippi and Watts2012), which showed a higher prevalence of pregnancy termination among women. The probable reasons could be the differences in socio-demograhic and economic characteristics such as affluence, employment, and geography of the studies’ settings, which have been linked to pregnancy termination. The high prevalence of pregnancy termination among urban-dwelling, employed women and those with the highest wealth level can be explained by the fact that the richest women can afford to terminate pregnancies because they are financially independent and typically reside in metropolitan regions (Dickson, Adde & Ahinkorah, Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018; Adjei et al., Reference Adjei, Enuameh, Asante, Baiden, Nettey and Abubakari2015; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014).

This finding aligns with findings from Kelly-Hanku (Reference Kelly-Hanku2013), where abortion was low in countries where the practice is restricted or prohibited by law and high among countries with no restrictions on the practice. The finding suggests that certain factors, such as the prohibition of abortion and other related practices under PNG laws, account for the relatively low rate of pregnancy termination in the country compared to results from other studies (Mosfequr, Reference Rahman2015; Dalal, Wang & Svanstrom, Reference Dalal, Wang and Svanström2014). Since abortion is prohibited in PNG, women may feel reluctant to report it, which may have accounted for the relatively low prevalence of termination of pregnancy (Lisa et al., Reference Vallely, Homiehombo, Kelly-Hanku and Whittaker2015). The high prevalence of IPV in PNG could be attributed to the high crime rates, poor social status of women, and societal norms and values that endorse IPV perpetration (Lisa et al., Reference Vallely, Homiehombo, Kelly-Hanku and Whittaker2015; Government of PNG et al., 2013; Kelly-Hanku, Reference Kelly-Hanku2013; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Bleakley and Ola2011). The individual, family, and community factors are crucial in deciding how much IPV is exposed to from an ecological standpoint (Adu et al., Reference Adu, Asare and Agyemang-Duah2022). Specifically, our finding aligns with Lisa et al. (Reference Vallely, Homiehombo, Kelly-Hanku and Whittaker2015) and Darko, Smith, and Walker (Reference Darko, Smith and Walker2015), which confirmed that physical violence is the most prevalent form of IPV in PNG.

In this study, women who had experienced IPV in the last 12 months prior to the survey were significantly more likely to terminate a pregnancy compared to those who did not experience IPV. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in Armenia (Samad et al., Reference Samad, Das, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Frimpong, Okyere, Hagan, Nabi and Hawlader2021), Bangladesh (Mosfequr, Reference Rahman2015), and Tanzania (Stockl et al., Reference Stöckl, Filippi and Watts2012), which revealed that being in an abusive relationship with an intimate partner may affect women’s reproductive decision-making, thereby resulting in pregnancy termination. Also, a similar study by Fanslow et al. (Reference Fanslow, Silva, Whitehead and Robinson2008) reported a positive association between IPV and pregnancy termination in New Zealand. In explaining this association, Fanslow et al. (Reference Fanslow, Silva, Whitehead and Robinson2008) noted that women who experience IPV may not be emotionally prepared to cater for the baby, thus opting for pregnancy termination. Pregnant women who suffer from IPV also experience mental health problems, which make them unprepared for childbirth, and this, in effect, may encourage such women to opt for pregnancy termination (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Bullock and Ferguson2017). Another possible explanation for the significant association between IPV and pregnancy termination found in our study and other previous studies could be that women in abusive relationships may have low autonomy over their sexual lives and hence can have more unwanted pregnancies (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Sasagawa, Fujii, Tomizawa and Makinoda2012) which in turn may increase the number of pregnancy termination. However, this study did not offer any evidence to support this assertion. Further studies can investigate whether IPV victims’ higher likelihood to terminate a pregnancy is associated with low autonomy over sexual lives. Also, it could be that in an abusive relationship, the partner/husband may not want the child and directly force the wife/woman to terminate the pregnancy. According to Mosfequr (Reference Rahman2015), IPV may increase the likelihood of unintended pregnancy by affecting post-conception and pre-conception desire for pregnancy, adaptions to pregnancy, and pregnancy preparations. These findings call for the need for government and policymakers to develop and implement measures and policies or interventions that address the perpetration of IPV in PNG.

Also, our study found that women from the urban centres, those within the richest wealth quintile, and employed women were significantly more likely to terminate their pregnancy than their counterparts. Consistent with a preponderance of evidence from China (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhang, Zhang, Jia, Li, Li and Sun2015) and Ghana (Adjei et al., Reference Adjei, Enuameh, Asante, Baiden, Nettey and Abubakari2015; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014) where women from urban centres, those within the richest wealth quintile, and employed women had higher odds of terminating their pregnancies. In contradiction to this finding, a previous study in Nepal (Tamang et al., Reference Tamang, Tuladhar, Tamang, Ganatra and Dulal2012) reported high abortion rates among rural women. However, Dalal, Wang and Svanström (Reference Dalal, Wang and Svanström2014) found no difference in the rate of pregnancy termination among rural and urban residents. This finding may be explained from the perspective that women from the urban centres may want to delay childbearing (Guttmacher Institute, 2010) and also, urban women who are mainly within the richest quintile and employed are financially stable and can afford to terminate a pregnancy (Dickson, Adde & Ahinkorah, Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018).

Our findings have some policy implications. Our findings highlight the need to implement and strengthen already existing programmes and interventions, such as establishing family support centres and family and sexual violence units that target women in intimate unions. The interventions should aim at reducing IPV to prevent pregnancy termination in the form of miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth. Implementing comprehensive sexuality education on the consequences of IPV, which may reduce the incidence of termination of pregnancy, is also crucial. Specific demographic and socio-economic variables such as place of residence, wealth status, and employment should be considered in the design of policies and measures to reduce pregnancy termination among women in PNG.

This study should be considered with some strengths and limitations. First, using nationally representative data from the first PNGDHS makes conclusions from our study representative. However, due to the cross-sectional of the study design, causal inference cannot be drawn from current outcomes. Also, the retrospective nature of reporting pregnancy termination subjects the data to recall biases.

Conclusion

This study has shown the association between IPV and pregnancy termination among women in PNG. Findings from this current study call for proven effective IPV reduction strategies and programmes targeting both men and women, such as developing, implementing, and strengthening interventions to address IPV in PNG to reduce pregnancy termination. The provision of comprehensive sexual reproductive health, public education, and awareness creation on the consequences of IPV, regular assessment, and referral to appropriate services for IPV may reduce the incidence of pregnancy termination in PNG. Further study is required to examine the IPV indicators (physical, spiritual, and emotional) against pregnancy termination among women in PNG separately.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the DHS. However, restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under licence for the current study; thus, the data are not publicly available. However, they can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request with the permission of DHS programmes.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the women who participated in the Papua New Guinea 2016–2018 Demographic and Health Survey.

Authors’ contributions

WA-D and BY-AA performed the conception, the design of the work, the acquisition, and the analysis. CA and AKA performed the design of the work and the creation of tables. CA and PP performed the design and drafted the work. All authors reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The current research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit source. No other entity besides the authors had a role in the design, analysis, or writing of the current article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required for this study since the data used for this study are secondary data. Necessary permissions and survey data were obtained from the DHS programmes. The DHS data upheld ethical standards in the research process.