Objects shape human existence. In recent years, particularly with the so-called material turn in various academic fields, there has been a meaningful theoretical reconsideration of objects and their relationships with people. Literary scholars too have recognized the importance of objects depicted within texts and have increasingly begun to explore their critical roles.Footnote 1 However, even with such renewed consideration of material things in literature, clothes are often overlooked or seen only as a tangential aspect of a text. This has certainly been the case for the kimono in modern Japanese literature.

The word “kimono” derives from “kirumono (literally ‘thing to wear’)” (Milhaupt Reference Milhaupt2014, 21); the kimono as a garment was a dominant part of Japanese clothing culture until the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 2 Since that time, however, kimonos have been eclipsed as everyday wear by Western clothes, and for many people they have become esoteric objects simply associated with “traditional Japan.” Although kimonos are still worn on occasion today, the various industries and practices involved in their upkeep, production, and retail have changed drastically or disappeared entirely. Because of such changes, understandings of both real and literary kimonos have significantly diminished.

Before this shift in clothing culture, however, most Japanese writers recognized what certain textile types, patterns, or styles could signify for their imagined community of readers, and informed readers could interpret kimonos through their own real-life experiences and familiarity with literary precedents.Footnote 3 Sartorial objects of material culture were an integral part of fictional texts, and readers could gauge how a character's kimono might represent such things as his or her inner self, age, and social and regional identity. Moreover, through kimonos readers could even access a greater world of possible signification that included authorial self-representation, symbolic meanings within the plot, haptic experiences, and even historical or social commentary.

The “language of clothes” (Lurie [1981] Reference Lurie2000), the idea that clothing “speaks” about the wearer's identity and the world he or she inhabits, has long been understood in disciplines such as anthropology, costume and fashion studies, folkloristics, and history. Scholars have examined specific Asian clothing, including the Indian sari, the Vietnamese ao dai, the Korean hanbok, and the Chinese qipao, to consider questions of self-fashioning, gendered and national identities, political expressions, concepts of the body, and the changing contexts and meanings of these objects. In engaging with issues of modernity, Orientalism, consumption, and contemporary globalization, scholars have also discussed East-West sartorial interactions.Footnote 4

Actual kimonos and what they say have also been the subjects of academic studies. For kimonos in contemporary Japan, Liza Dalby uses terms such as “kimonese,” “language of kimono,” and “kimono grammatical rule” to discuss protocols and what is conveyed through dress (Dalby [1993] Reference Dalby2001, 163, 168, 176). Others have explored how the wartime kimono articulates propaganda (Atkins Reference Atkins and Atkins2005; Kashiwagi Reference Kashiwagi and Atkins2005; Wakakuwa Reference Wakakuwa and Atkins2005), and Terry Satsuki Milhaupt's recent work on the kimono from the seventeenth century to the present illuminates the changing meanings expressed through this item over time (Milhaupt Reference Milhaupt2014).

Despite such studies of actual kimonos, however, fictional kimonos in modern literature have been understudied. Literary kimonos certainly function to create what Roland Barthes (Reference Barthes and Howard1986) has called “the reality effect,” in which descriptive objects provide verisimilitude in fiction without referring to anything beyond themselves. But kimonos in literature also speak loudly of many things beyond themselves, communicating information about characters, plot, social context, and so on. Through descriptions of individual kimonos, kimono production, consumption, maintenance, exchange, and reuse, texts offer various layers of meaning and possibilities for interpretation.

In a discussion of late Victorian women's fiction, Christine Bayles Kortsch (Reference Kortsch2009, 4–5) uses the term “dual literacy” to suggest that writers crafted their works through female literacy in “dress culture” as well as in the written word.Footnote 5 In order to fully appreciate such texts, she suggests, we need to understand the material world of clothing, textiles, sewing, and what these conveyed to readers of the time who were conversant in this language. This concept of dual literacy is useful for thinking about kimonos in Japanese texts, works written at a time when both writers and readers could share (or were perceived to share) certain knowledge about kimono culture. Fluency in kimono language includes the ability to recognize kimono types, fabrics, designs, related vocabulary, and what such things signify, as well as the ability to interpret this signification in the context of human-kimono interactions.Footnote 6

But the notion of literacy in clothes can be complicated, and post-mid-century Japanese texts that use kimono language especially present unique challenges. What happens when the author is fluent in the language of kimono but is also intensely aware that she is writing at a time when her readers’ facility with this language is disappearing? Does her literary production and expression change in a world where both the material object (kimono) and its associated language are shifting? And after she herself dies, how does the text live on—rewritten or reread—through its continued engagement with an evolving object?

These questions undergird this essay, an examination of author Kōda Aya (1904–90), her unfinished novel Kimono (1965–68), and its afterlife during the 1990s–2000s. I show how Kōda utilizes different levels of kimono language and also develops the trope of kimono as a vehicle for human development. Kimonos are garments that mark age and social roles, but in this novel set in prewar Japan, they are also objects that provide life lessons for the wearer. By listening to what kimonos say, by being educated through them, Rutsuko, the protagonist of the novel, grows up to find herself and attain agency.

In addition to interpreting the fictional world within the novel, I also use the kimono as a tool to look at the text from the outside, to explore how a material object can allow us to read literature extratextually. This endeavor contributes to broader theoretical discussions on the uses of objects in literary analysis and opens new interpretive avenues for considering the “afterlife” of a text. In this case, the kimono speaks to a number of significant aspects outside the immediate confines of the novel: the author's self-representation during the 1950s, the social context of the 1960s in which the text was written and then abandoned, and the novel's reemergence during the 1990s and the 2000s. Indeed, Kōda's Kimono has had a unique “afterlife,” posthumously published in book form for the first time in 1993 and revitalized through the essays of her literary inheritor, daughter Aoki Tama (1929–). I explore these extratextual aspects in order to create different ways of reading Kimono. I also show how Aoki, in her own writing, emphasizes aspects of Kōda's works for a contemporary readership.

Kōda has long been recognized as a literary inheritor, carrying on the legacy of her famous father Kōda Rohan (1867–1947). By focusing on the kimono, an object that eloquently expresses transformation as well as historical and literary connections over time, I suggest new approaches for understanding Kōda Aya, including a fresh view of this author, not only as a literary inheritor but also as a literary progenitor, whose tropes and concerns are taken up by her own daughter.Footnote 7 Moreover by engaging with contexts of production and posthumous reproduction, I present a new way of interpreting Kimono, and by extension, other texts featuring things.

Indeed, although I discuss a particular case within modern Japanese literature using a particular object of dress, this essay also addresses broader concerns within studies of materiality and cultural representation, especially interactions between humans and things, and how objects speak through texts. By focusing on “things-in-motion” to “illuminate their human and social context” (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986, 5) and considering “the cultural biography of things” (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986), I demonstrate how objects can serve as entryways into literature, allowing us to discover new meanings for both material things and narratives.

Reading Kimono

Of the postwar Japanese authors who wrote about kimono, Kōda Aya is perhaps the best known. She is recognized as a kimono practitioner and specialist of sorts, who consistently wore the garment all her life, even into the postwar era when Western clothes overwhelmingly became the standard.Footnote 8 Kōda's literary career started at age forty-three in 1947, when she began publishing essays about life with her father, Kōda Rohan, after his death. Readers were intrigued by the contrast between the daughter, who had spent most of her life in the domestic world of cooking and cleaning, and the father, a representative Meiji writer. Kōda Aya also went on to write short stories and novels, becoming a respected author in her own right. As both Ann Sherif (Reference Sherif1999) and Alan Tansman (Reference Tansman1993) have detailed in their respective monographs about Kōda, she has a critical place in the landscape of postwar Japanese literature. Her first collected works (zenshū) was published in 1958–59, only eleven years after her literary debut, attesting to critical and popular interest. After her death in 1990, her writing was again in the limelight, particularly with the 1994–97 publication of her twenty-three-volume collected works.Footnote 9

Kōda's Kimono, serialized from June 1965 to August 1968 in the journal Shinchō, features everyday kimono culture in early twentieth-century Japan. The work is a kind of “bildungsroman (kyōyō shōsetsu)” (Tsujii Reference Tsujii and Kōda1996, 366) depicting the protagonist Rutsuko's coming of age; as Sherif (Reference Sherif1999, 140) has illustrated, “kimonos are the means by which Rutsuko comes to develop her own sense of personhood.”Footnote 10 A character who resembles Kōda in some respects, Rutsuko learns about kimono primarily from her grandmother, a wise female mentor. Through encounters with different kinds of fabrics and outfits, Rutsuko not only begins to understand her own sartorial and sensory preferences, but also establishes her worldview and identity. Because Kōda stopped serializing the work in 1968, however, Rutsuko's story was never completed. The unfinished serialization was first published in book form in 1993, several years after Kōda's death.

In this novel, Kōda illustrates the everyday world of 1910s–20s Tokyo, in which the kimono was a fundamental presence. She portrays this past world for a 1960s readership whose relationship with kimonos differed significantly: by the early 1960s, scholars were already explaining that in Japan the kimono was “dying out as a form of every-day dress” and “reemerging as a form of ceremonial or formal dress” (Nakagawa and Rosovsky Reference Nakagawa and Rosovsky1963, 80). In her novel, Kōda describes the tactile qualities of different fabrics and intimates what styles, colors, and patterns may say about the wearer. Through depictions of everyday life, she also reminds readers that the kimono used to be a garment commonly made at home and constantly recreated and changed into other things. Although a kimono has the semblance of finality, handed down over generations, it can be taken apart, washed, resewn, relined, redyed, turned into other kimonos, and (when well worn) made into other household items such as futon bedding. As new bolts of fabric and later as second-hand clothing, kimonos were also important items of economic exchange, used as gifts, payment, and objects to pawn.

Kimono begins with Rutsuko as a child, being reprimanded by her family for having ripped a sleeve off her dōgi, an undergarment padded with cotton, because it was uncomfortable: “The one torn sleeve was placed in the middle, and Rutsuko, her grandmother and mother sat in a triangle around it” (Kōda Reference Kōda1996b, 4).Footnote 11 As this opening suggests, Rutsuko's identity is defined through clothes and the human relationships that develop around them. Her sense of well-being is directly influenced by clothes, and she makes unconventional (often unfeminine) choices in pursuit of this sense of comfort. Throughout the work, we see a strong connection between Rutsuko's physical and mental happiness and kimonos; for instance, she breaks out in hives when wearing a kimono made of merinsu or seru (types of woolen fabric) and one time even fails a school entrance exam because of an ill-fitting kimono.

Kōda often uses the dialogue between Rutsuko and her grandmother to elaborate on what is signified by specific textiles and patterns. This work is certainly not a kimono dictionary or a reference manual, but by showing how Rutsuko learns from the grandmother, Kōda is also able to teach 1960s readers how to “read” kimono accurately. Through the narrative, Kōda implicitly educates readers about different types of fabric and designs, and also guides them in the art of interpreting what they signify. Learning alongside Rutsuko, readers thus improve their fluency in kimono language.

For example, Rutsuko's favorite kimono, one she wears throughout her youth, is made of habutae, a smooth silk used for formalwear, with a checkered design. She encounters this item in a pile of discounted cloth at a kimono dealer's establishment, and it is the first fabric she ever chooses by herself. Through prior conversations and episodes, both Rutsuko and readers along with her have learned that this is a masculine cloth unusual for a women's kimono; later they further come to realize that this combination of expensive textile with checked pattern is also rather rare. Because checks are an everyday pattern unusable in formalwear, most people would find this fabric undesirable. Indeed, readers ultimately realize that this kimono is distinct from conventional kimonos worn by girls of Rutsuko's age, and therefore reflects her unusual aesthetic and haptic tastes. Through Kōda's presentation of Rutsuko's education, readers are guided to recognize that the garment she selects is a one-of-a-kind item that defies standard rules of gender and age appropriateness, and also that it reflects Rutsuko herself. She is an unconventional, special character who is overlooked by most people but appreciated by those able to value unexpected treasures.Footnote 12

Rutsuko grows up learning rules, methods of care, and other basics about kimonos, and accumulating tactile knowledge and sensory experiences. But ultimately, being able to read kimono well is not just about knowledge of fabrics, patterns, and protocol. Throughout the novel, important formative experiences are mediated through kimonos, such as her first encounter with male sexual desire when wearing a kimono that enhances her figure, or her experience of sewing a yukata nightwear for her sick, bedridden mother. Rutsuko learns to see that kimonos are a critical means of self-presentation through which to understand herself and the world in which she lives (see Sherif Reference Sherif1999, 141–45). Rutsuko also comes to appreciate the kimono as a kind of currency that teaches valuable life lessons, such as how and what to give others, what one can or should receive in exchange, and what is truly essential in human life.

Echoing the biblical Ruth (Rutsu), Rutsuko's name underscores her loyal role within the family and also suggests her select status.Footnote 13 In effect, Rutsuko grows up to be an ideal reader of kimono who understands meanings beyond aesthetics or taste. As such, she is contrasted with her eldest sister, a mean-spirited, superficial reader who appears as Rutsuko's direct foil in the story. When they are at their mother's funeral, for example, the difference in how the sisters read kimono is evident. Rutsuko attends the event wearing a dark purple silk iromuji (colored monochrome kimono) with a single family crest, given to her by her grandmother, who helped her prepare for the ceremony. Seeing this choice of funeral wear, appropriate for an unmarried young woman, the eldest sister grins knowingly and comments:

You did well, asking for such a nice kimono. Was it a reward for taking care of the sick patient [their mother]? I'm jealous that purple looks so wonderful against your pale skin. But why did you choose to use a harimon [family crest made on a separate fabric and patched on]? That is so déclassé (gesuppoi). (Kōda Reference Kōda1996b, 260)

The sister only sees this kimono as a “reward” that Rutsuko successfully managed to snatch up. She congratulates her on this addition to her property, but asks with disdain why the family crest did not appear directly on the kimono fabric itself. The wealthy, impeccably dressed, married sister questions the harimon, which she considers the wrong choice for this outfit.Footnote 14

In contrast to the earlier example of Rutsuko's favorite kimono, in which Kōda implicitly educates readers in kimono language by explaining about habutae and the checked pattern, this is an example in which Kōda assumes knowledge of her readers. In this episode, she does not explain what a harimon is, or why it is there. The harimon is an obscure term for readers today, but many 1960s readers would likely have still understood it. The desired type of formal family crest (and one that the sister would presumably have preferred) is a “dye-reserved crest” (Dalby [1993] Reference Dalby2001, 183), made by reserving the white color of the kimono fabric itself before it is dyed. For a single-crested kimono, the family crest appears on the back of the kimono, below the neck (see figures 1, 2, and 3). Unlike a crest made on a new bolt of cloth, the harimon suggests the reuse of an older kimono.

Figure 1. An example of a dye-reserved crest on the back of a light blue women's iromuji (colored monochrome kimono). A one-crest kimono made of a wave pattern textured silk worn with a gold and muted pink brocade obi sash. Photo by M. D. Foster.

Figure 2. Close-up of the crest. Photo by M. D. Foster.

Figure 3. The iromuji with the crest. Photo by M. D. Foster.

Although the story does not clarify the reason for its use, the harimon—dyed out on a separate, small piece of cloth—was likely affixed onto a kimono with no crest, used to cover over a different family crest, or patched over a crest that had become discolored or imperfect in some way due to the process of remaking a used kimono. Its use hints at economic considerations and the limitations that the grandmother faced in the dyeing and resewing of an old kimono into a suitable outfit for Rutsuko. Although the one-crest kimono appears as “proper mourning clothes,” if one looks carefully it is a “cobbled together funeral outfit” (Kōda Reference Kōda1996b, 257, 260).

The sister's question is likely ironic, and she may be well aware of the fact that the harimon was used out of necessity because of the downturn in the family's finances and the inability of the family to purchase a new kimono. Even so, Kōda shows the sister as a limited reader of kimono because she cannot see what it signifies beyond monetary worth and aesthetics. Rutsuko says nothing in response to her sister, nor does she analyze what the harimon signifies in the story, but it is clear that for her, and for the readers as well, this funeral kimono speaks of a complex network of human relationships, values, and emotional connections. The sister's reading is purely on the surface, associating the harimon with Rutsuko's lack of taste or finances. The deeper meaning of this harimon that Rutsuko and the readers access is her grandmother's thoughtfulness and resourceful housekeeping abilities, the intimate relationship between Rutsuko and the grandmother, and Rutsuko's own continued commitment to the family. Through such episodes, Kōda implicitly educates us in becoming skilled readers of kimono and shows the importance of cultivating such interpretive insight.

The text includes many other valuable lessons. For example, kimonos provide Rutsuko with agency. As apparel layered and wrapped around the body and secured only with various cords and an obi sash, a kimono expresses the skill with which it is put on, worn, and accessorized. Rutsuko's grandmother specifically trains her to master the art of self-dressing, to be able to wear different kimonos by herself while achieving comfort and style. Unlike the eldest sister, who needs Rutsuko and others to help her dress at important moments in life, Rutsuko is independent.

More broadly, the kimono also teaches Rutsuko (and readers) to think about the deeper meaning of clothing in the context of national history. In the latter part of the narrative, Rutsuko's family experiences the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, one of the largest disasters of early twentieth-century Japan. One estimate notes 143,000 dead or missing, 128,000 homes destroyed, and 447,000 homes burnt in the greater Tokyo area (Wada Reference Wada and Hirofumi2007, 609). Rutsuko's family members survive, but lose their home in the fires caused by the earthquake; they are left with nothing but, literally, the clothes on their backs.Footnote 15 The devastation depicted in the text concerns a 1923 event, but also closely echoes experiences of World War II, particularly with its focus on fire (bombs) and the loss of basic material needs (food, shelter, and clothes). During and immediately after the war, many kimonos were burnt in air raids or lost in the process of bartering for food and other necessities. Even if readers did not personally experience the so-called “bamboo shoot life” (takenoko seikatsu) in which people lived hand to mouth by peeling off layers of clothing and belongings one by one and selling them to survive, such images of deprivation and lack had become a significant part of the cultural imaginary about the war. Rutsuko, left wearing only an old cotton yukata, comes to the realization that the “fundamental starting point of clothes” is to cover the flesh and to protect oneself from the cold (Kōda Reference Kōda1996b, 341). Her education consists of understanding, wearing, making, giving, and receiving kimonos, but from this moment also entails a rebuilding of her life while keeping this “starting point” in mind. For 1960s readers, this education enables reflection on the national past and the subsequent path since the end of the war; they are reminded of what is most important about dress, as well as the losses and gains incurred through Japan's postwar recovery.

Life and Death of Kimono: The 1960s

Certainly Kimono looks to the past in many ways. It can be read as a semi-autobiographical reference to the days of Kōda's youth, a bildungsroman retracing individual and national growth, or an education in kimono literacy that celebrates prewar dress culture. As Sherif (Reference Sherif1999, 135) notes, the novel, set in the early twentieth century, paid “homage to the end of the age of kimono,” but as a publication serialized in the 1960s also “rode the crest of the kimono boom occasioned by the return of economic prosperity in postwar Japan.” Indeed, it is critical to analyze this novel not only in relation to prewar Japan, but also in the context of its publication during the rapid economic rise of the 1960s. Kimono is simultaneously an exploration of the past and also a discussion of contemporary life: how humans and objects engage and shape each other in a world filled with things. This lesson was vital for the 1960s in which kimonos had become transformed in real life; they were no longer a dominant part of the average Japanese wardrobe and thus were “dying” objects of the past, but at the same time they were also very much “alive” in the present as outfits for special occasions, manifestations of specific fashion trends, and expressions of nostalgia and national identity.

Liza Dalby ([1993] Reference Dalby2001, 131) has noted that the “kimono was resurrected in the 1950s, and continued to grow in popularity during the 1960s in what the Japanese called a ‘kimono boom.’”Footnote 16 The year 1965, for example, when Kōda began serializing Kimono, is recognized in fashion history as the year of the “wafuku (Japanese wear) revival,” in which matching kimono and haori (kimono jacket) ensembles for men sold well, and fashionable mothers began wearing black haori over iromuji to formal school events in what came to be known as the “PTA look” (Shimokawa Reference Shimokawa2001, 342, 344; Yanagi [1985] Reference Yanagi1989, 159–60). Kōda herself wrote an essay on the black haori phenomenon in 1968, addressing its popularity for women (Kōda Reference Kōda1996c, 20–25; see figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. An example of a black haori from the early 1970s worn by a young mother to formal school events. Courtesy of Taoka Noriko. Photo by K. Suzuki.

Figure 5. Back of the black haori showing a continuous pink landscape scene, featuring abstracted black pine trees with gold embroidery, and a single family crest. Courtesy of Taoka Noriko. Photo by K. Suzuki.

With the so-called “Izanagi economic boom” (Izanagi keiki), by 1968 Japan's GNP rose to second place in the world as a capitalist nation after the United States (Iwanami shoten henshūbu Reference Iwanami shoten1991, 456, 466; Masuda Reference Masuda2010, 366). If we read kimono specifically as “a symbol of national consciousness” (Nakagawa and Rosovsky Reference Nakagawa and Rosovsky1963, 80), the 1960s kimono boom may be explained as a rediscovery of Japanese identity. And as scholars have shown, discourses on the kimono even became part of ethnocentric Nihonjinron (theories of the Japanese) (Dalby [1993] Reference Dalby2001, 141–43; Gordon Reference Gordon2012, 194). Certainly, with economic prosperity and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the desire for kimonos may have been partly due to a broader interest in Japanese culture and a sense of an authentic or exotic national identity. Yet rather than viewing this rise in select kimono fashions only as an expression of nationalism or a return to Japanese dress, it is important to understand how this phenomenon also features as part of the broader dynamic consumerism of the 1960s. The “three sacred treasures” of the 1950s, that is, the black-and-white television, laundry machine, and refrigerator, were replaced in the 1960s by the “3C,” the color television, car, and “cooler” (air conditioner) (Masuda Reference Masuda2010, 366–67; Sesō fūzoku kansatsukai Reference Sesō fūzoku2001, 186; Shimokawa Reference Shimokawa2001, 356; Yanagi Reference Yanagi1983, 331). The surge in consumption of these and countless other new products, as well as increased spending on leisure activities, such as travel and entertainment, reflected the emergence of a new consumer lifestyle (see Yanagi Reference Yanagi1983, 331).

Indeed, in 1968 many women may have owned black haori, but they were also wearing other contemporary fashions, including flared trousers (pantalon), mini-skirts (particularly popularized by the British model Twiggy's 1967 visit to Japan), as well as skirts of other lengths such as the midi and maxi (Masuda Reference Masuda2010, 373; Sesō fūzoku kansatsukai Reference Sesō fūzoku2001, 187, 192–93; Shimokawa Reference Shimokawa2001, 339, 362, 368, 370). By this time, clothes were becoming something to be bought ready-made, and also considered items for enjoyment, not worn just for practical purposes (Yanagi [1985] Reference Yanagi1989, 107–8).Footnote 17 Within this context, the 1960s kimono was part of a new fashion culture that cultivated access to various kinds of apparel and different means of self-expression. The rise in personal wealth, the increase in consumer choice, and the expansion of leisure opportunities fueled the kimono boom.

Considered from this perspective, Kōda's novel also resonates as a reassessment of 1960s society in which individuals “sought identity in consumer culture” (Yanagi Reference Yanagi1983, 331). It is important that Rutsuko's identity is constructed through kimonos: not as a consumer who expresses herself through accumulation and trends, but as a producer able to fully utilize limited resources and recreate their form and meaning (making her worn-out favorite kimono wearable with a hakama overskirt; turning the forgettable childhood chirimen silk kimono into a valuable futon for her mother). Rutsuko also exhibits an engaged intimacy with kimonos that had disappeared from the average 1960s Japanese household, such as expertise in kimono management (mending, washing, cleaning, remaking).

While developing such abilities, Rutsuko acknowledges the power of kimonos; at times they seem to act on their own, taking their owner in unexpected or unwanted directions. Her meisen silk kimono teaches her an unwelcome lesson in male sexual desire: a pervert ejaculates on Rutsuko in a crowded train and her grandmother suggests that the striped design of the kimono had showed off her figure too clearly. Rutsuko's kimono, torn when she is hit by a bicycle, becomes a catalyst for her to fall in love with her future husband, a bystander who helps her home from the accident scene. Formation of her mind and body takes place through the exchanges that occur between kimono, herself, and others; meaning is not simply given to an inanimate item, but is created in the dynamic interaction between things and people.Footnote 18 In this sense, Kimono is a novel that emerged from the 1960s economic miracle, in that it clearly grants authority and significance to objects. But at the same time, by depicting Rutsuko's meaningful and close relationship with kimonos, it questions the new consumerism and the burgeoning culture of abundance. Even as the novel looks to the past, it is also very much engaged with the 1960s present in which the kimono is alive—but as only one object among an endless array of products and consumer choices.Footnote 19

Kimono ends on Rutsuko's wedding night as she is being undressed for the first time by her husband. The novel had opened by highlighting Rutsuko's agency, as a girl who rips the sleeve off her uncomfortable underjacket. In contrast, the ending shows her being disrobed by another: “The underclothing made a sound sliding down her hips, being removed by another's hands, not hers.” This event, described as “a marital ceremony that was proceeding smoothly” (Kōda Reference Kōda1996b, 421), is depressing in tone and depicted without romance or sentiment. The scene clinically presents Rutsuko's loss of agency and underscores an earlier suggestion in the text that the marriage was a mistake (418–19). It questions the future of this couple (Yuri Reference Yuri2003, 154) and, as novelist and critic Mizumura Minae ([1993] Reference Mizumura2009, 35) suggests, negatively foreshadows what is to come, intimating that Rutsuko will ultimately reject this marriage, just as she has refused to wear certain kimonos in the past.Footnote 20

Because of the striking resonance created between the opening and the close of the novel through the image of disrobing, it is easy to forget that Kimono was never actually finished, and that Kōda abandoned the serialization after August 1968.Footnote 21 Although she originally had planned to continue Rutsuko's story, Kōda became too busy with other projects to complete the work.Footnote 22 She became passionately involved in the reconstruction of a pagoda at Hōrinji temple in Nara, raising money, observing carpentry work, and even living nearby during 1973–74. She also serialized essays such as Ki (Trees, 1971–84) and Kuzure (Landslides, 1976–77); these works were posthumously published in book form in 1992 and 1991 respectively, and were considered a reflection of her new interest in natural phenomena (see Aoki Tama Reference Aoki1997, 99–104; Reference Aoki2006, 180–82; Kojima [1995] Reference Kojima2003).

But there was another reason she ceased serialization of Kimono. Her daughter Aoki Tama explains that she had tried to persuade her mother to continue the serialization, but Kōda had refused, citing the decline of kimono culture. Aoki paraphrases Kōda:

No matter how much I write about the fun, beautiful, and interesting aspects of kimono, it doesn't mean much if there is no one actually wearing them. When I was writing Kimono there was still something that was mutually understood, but as time passes by, it [the kimono] is no longer even something to be enjoyed but has moved farther and farther away. If there is no mutual feeling (kyōkan), no one will read it [the work]. (Aoki Tama Reference Aoki2006, 183)

In a sense, Kōda is refusing to speak a language that is no longer widely understood. By describing and explaining textiles, tactile sensations, design, protocol, daily practice, and kimono-human connections, she celebrates the rich kimono culture of the past. But the very act of writing about it contributes to its fossilization; it becomes a carefully preserved relic of sorts, to be admired in a museum. Perhaps Kōda is imagining readers who, when reading about Rutsuko's funeral wear, will vaguely wonder, “What is a harimon?” instead of grasping the various ramifications of its meaning. For Kōda, the kimono is still alive, but she recognizes with mixed emotions that like the kimono, she herself is becoming a remnant of the past. In Landslides she comically depicts how uncomfortable she feels in trousers, comparing this to the pain that “young women who were raised in Western clothes” feel when wearing kimonos. Despite the postwar kimono boom, those who shared Kōda's “seventy-odd years” of kimono life were disappearing (Kōda Reference Kōda1996e, 45–48).

Author and Book as Kimono: The 1950s

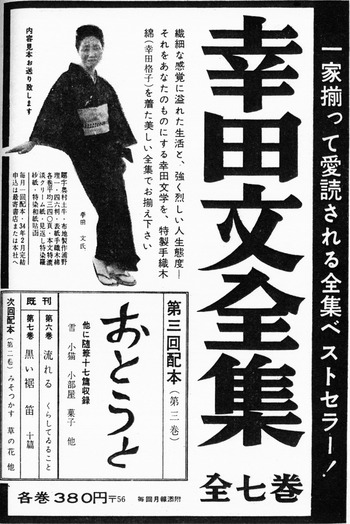

Kōda's abandonment of the novel is particularly poignant because of the close association of author and text. In addition to a few autobiographical elements in the novel itself, Kōda herself has been represented as kimono in a variety of different contexts. Indeed, the association between Kōda and the kimono had been well developed since the 1950s, through her fiction, essays, and collected works. She was known for stories that presented kimonos in memorable ways, such as “Kuroi suso” (Black hem, 1954), about a woman's life depicted through funerals and mourning kimono, and Nagareru (Flowing, 1955), which explores the disappearing world of kimono-wearing women of the demimonde. Kōda also wrote many essays about the kimono during the 1950s and 1960s. A significant landmark, however, was the seven-volume Kōda Aya zenshū (Collected works of Kōda Aya) published by Chūōkōronsha in 1958–59, which literally wore kimonos: the book covers themselves were made of handwoven cotton kimono fabric with a checkered pattern, dubbed the “Kōda check” (Kōda gōshi) (see figure 6).Footnote 23

Figure 6. Kōda Aya zenshū with the “Kōda check” cover (Kōda Reference Kōda1958).

The idea to produce her collected works in this way, an inspired commercial move, is thought to have been the brainchild of the president of Chūōkōronsha, a major publishing firm at the center of the literary world (Fujimoto Reference Fujimoto, Kanai, Kobayashi, Satō and Fujimoto1998, 91). These collected works dramatized the Kōda gōshi as Kōda herself, the kimono fabric speaking volumes, as it were, about the author and her works. Designed by a master dyer based on a “late Edo-period” pattern and “woven in a Tanba region style of traditional mingei [folk art] cloth” (Aoki Nao Reference Aoki2011, 51; Fujimoto Reference Fujimoto, Kanai, Kobayashi, Satō and Fujimoto1998, 92), Kōda gōshi conveyed a certain image of Kōda and her art.Footnote 24 Historically, cotton cloth such as this was an everyday staple, dyed and woven at home. In kimono protocol, such fabric is considered lowest in terms of rank and limited to casual wear (see Dalby [1993] Reference Dalby2001, 173), as is the checked pattern. Thus, in contrast to formal silks, such cotton fabric of muted checks suggested earthiness, resilience, and everyday culture. But already by the late 1950s, this sort of handwoven kimono had also come to be appreciated as a valuable example of mingei, reflecting hand-made authenticity, high quality, and cultural significance.Footnote 25 These contrasting impressions were used to promote Kōda's collected works as those of a down-to-earth, everyday, yet serious and important author.

Chūōkōronsha magazines Chūō kōron (Central review) and Fujin kōron (Women's review) systematically advertised the “beautiful collected works wearing … Kōda gōshi” (Chūō kōron 1958b, 1958c; Fujin kōron 1958b, 1958c) during 1958–59 (see figure 7). Many of the advertisements highlight the cloth cover, and in one ad, novelist Kawabata Yasunari proclaims that Kōda's literary works “are reminiscent of Japanese handwoven fabric” (Chūō kōron 1958a; Fujin kōron 1958a; see figure 8). The July 1958 issue of Fujin kōron featured a special photograph series showing Kōda wearing a kimono made of this fabric and visiting the weaving factory in Nagano prefecture, thus making a clear connection between the kimono-wearing volumes and the author herself (Fujin kōron 1958d). To commemorate the publication, the company also gave away this kimono fabric to 100 people, announcing the winners in the May 1959 issue of Fujin kōron with a picture of Kōda attending the lottery selection (Fujin kōron 1959).Footnote 26

Figure 7. An example of such advertisements, from the Chūō kōron November 1958 issue (Chūō kōron 1958c). This one includes a photo of Kōda Aya in a kimono.

Figure 8. The advertisement from the Chūō kōron July 1958 issue that includes an image of the collected works (Chūō kōron 1958a).

In the 1950s, the association of Kōda, her works, and the cotton kimono fabric conveyed a powerful message that could be easily understood: Kōda and her works are rare and valuable, but also folk-oriented and accessible. The gendered aspect of her identity was highlighted with this connection to a coveted kimono fabric for women; yet unlike decorative silks, this particular fabric did not emphasize her femininity in a way that undermined her seriousness as a writer. This connection of author-kimono-book also provided consumers the satisfaction of owning an authentic item without appearing superficial or materialistic.

During the late 1950s, weavers were still able to produce such kimono fabric on this scale by hand. Aoki Nao (1963–), Kōda's granddaughter (Aoki Tama's daughter), writes about Kōda gōshi in her 2011 essay collection Kōdake no kimono (Kimonos of the Kōda family, 2011).Footnote 27 She consults records and finds out that because Kōda gōshi was handwoven, “one loom could only produce a single tan [the standard fabric length for making one adult kimono] per day,” enough to cover “fifty-three books.” “The collected works had seven volumes each … and tens of thousands of books were sold. Thousands of tan of this cloth were created entirely by hand in the short space of eight months during the publication of the series” (Aoki Nao Reference Aoki2011, 52).

By contrast, it is worth noting that in 1972, when Miyao Tomiko, another writer associated with kimono, decided to self-publish her first book with a kimono fabric cover, it had become difficult to find tōzan, a type of everyday striped cotton. She needed covers for only 500 books, but even after consulting a well-known firm, only machine-woven cloth was available and she had to make her selection from limited pattern choices (Miyao [1983] Reference Miyao1993, 413–14).Footnote 28 Other factors were certainly involved here, but Miyao's experience provides a snapshot of the decline of the everyday kimono during this period. By the time Aoki Nao wrote about the Kōda gōshi, most of the fabric swatches from its late inventor's collection had become pieces of history; with the disappearance of artisans and materials it was no longer possible to produce this kind of kimono cloth. And Kōda's own kimono made of Kōda gōshi had followed the fate of all well-worn casual wear, surviving only as scrap remnants (Aoki Nao Reference Aoki2011, 54, 56).

The postwar revival of kimono during the 1950s–60s invigorated Kōda's writing and helped boost her popularity. But even as she herself became synonymous with the kimono, Kōda was observing its decline. In a 1958 essay praising the kimono as a means for creative self-expression, she articulates her desire to “transmit everything one knows to the inheritors [of kimono knowledge, who will wear kimonos at most just several times a year]” so that the “life” (seimei, inochi) of kimono will continue. At the same time, she makes a self-deprecating comment about this endeavor, saying that for the next generation, such knowledge might only be “something unwanted, like garbage” that an old woman is pushing them to accept (Kōda Reference Kōda1995, 312, 314–15).

For the most part, Kōda's kimono essays do not require readers to have expert knowledge of kimono for full comprehension. This reflects their function as descriptive tutorials, written for an audience that required an introduction to the historical past of kimonos as well as protocol, manners, and taste.Footnote 29 Only a few early essays, such as “Kimono sandai” (Three stories of kimono, 1948), demand high-level kimono literacy of readers. The humorous exchange in this work between the ikebana (flower arrangement) teacher and Kōda Rohan is completely opaque to the uninitiated; it can only be fully understood by a reader who knows the pitfalls of wearing a linen kimono and the unsightly bodily movements required to fix wrinkles—none of which is explained in the text itself (Kōda Reference Kōda1994, 315–16).

In general, however, Kōda did not write about kimonos in this way during the 1950s–60s. Instead, she wrote about them in an approachable fashion in her essays, stories, and novels, explicitly or implicitly teaching readers who could no longer be expected to have in-depth understanding or familiarity. In Kimono, Kōda takes this stance in communicating to a broad spectrum of readers the experience of growing up and being “educated and nurtured” (Kōda Reference Kōda1996d, 304) by kimonos. In the context of social and sartorial changes, however, she would ultimately abandon such efforts to weave her story around a dying object, leaving Kimono unfinished.

Remaking Kimono

On one level, Kōda's predictions about the decline of kimono culture came true after the 1960s. From 1973 to 1981, the market for kimonos was cut in half, and in the next ten years it decreased by another 50 percent (Matsubara Reference Matsubara2010, 99). Despite this, however, Kimono and the messages at its core lived on through its publication, as well as its revitalization in the works of Kōda's daughter, Aoki Tama.

After Kōda died in 1990, many of her serialized works were published as books for the first time, including Kimono in 1993.Footnote 30 Although many authors enjoy a revival and surge in sales after their death, Kōda was given particular revalidation by the literary world. In 1993, critic Nakano Kōji analyzed this posthumous rediscovery of Kōda and posited that her works spoke to the current times in which “the Bubble has burst.” The trendy novels of the late 1980s, the so-called Bubble economy period, featuring urban lifestyles and youth culture, had become irrelevant, while her “honed writing has begun to shine like a well-worn piece of cloth washed numerous times.” The view that a shift from “quantity to quality” (Nakano Reference Nakano1993, 229) had occurred may be a bit schematic, but it is useful for thinking about Kimono and its inherent message advocating a meaningful relationship with the material world. The novel gained new relevance in the post-Bubble era of the 1990s, when upscale brands and overconsumption had become gauche and a more personal, unique experience with objects had come to be deeply desired.Footnote 31

Aoki Tama, in her own writing, highlights such aspects of Kōda's novel, its validation of lasting intimacy between humans and objects, and its celebration of kimono as a vehicle of complex signification and female self-development. With Kōda Aya no tansu no hikidashi (Inside Kōda Aya's kimono dresser, 1995; hereafter, Kimono dresser) and Kimono atosaki (Kimono before and after, 2004–5), essay collections with detailed photographs, Aoki cultivated a new audience for her mother's works during the 1990s–2000s (see figure 9).Footnote 32

Figure 9. Aoki Tama, Kimono atosaki (Kimono before and after). The cover includes a photograph of Aoki Tama in a kimono (Aoki Tama [2004–5] Reference Aoki2006).

Like Kōda, Aoki debuted as an essayist by writing about her family after the death of her parent; committed to preserving the family legacy, she began to write in her sixties in order to promote her mother's works. Aoki's first book, Koishikawa no uchi (The house in Koishikawa, 1994), provides a new look at the relationship between herself, her mother, and her grandfather, a reframing of Kōda's famous essays about Rohan from a different point of view (Aoki Tama [1994] Reference Aoki1998). In addition to works that closely engage with Kōda's writing, Aoki participated in the editing of her mother's posthumous publications, including Kimono and the 1994–97 collected works.Footnote 33

In Kimono dresser and Kimono before and after, Aoki explicitly uses the kimono as an object that connects herself to her mother, grandfather, and daughter, and also frames her writing as an extension of her mother's literary endeavors. In the afterword of Kimono before and after, for example, she expresses deep regret for not having been able to persuade her mother to continue the serialization of Kimono. This is explained as one of the motivating factors for Aoki's own commitment to promoting kimono culture and its enjoyment, and expressly ties her essays to her mother's novel (Aoki Tama Reference Aoki2006, 188–89).

Kimono dresser and Kimono before and after feature discussions and photographs of family kimonos. The former highlights Kōda's kimonos and the mother-daughter relationship, and the latter especially shows how Aoki, in the process of remaking her inherited kimonos, builds connections with weavers, dyers, cleaners, and designers. Both works value personal relationships with material objects and the human relationships that develop around them. The essays also educate readers in various aspects of kimono design and maintenance, practices, and appreciation. Kimono dresser, published soon after the book launch of Kimono, especially provides readers with insight into the types of kimonos discussed in the novel, as well as the link between the fictional Rutsuko and the “real” Kōda Aya.

For example, in “Tagasode” (Whose sleeves), an essay in Kimono dresser, readers discover that the cover design of the 1993 Kimono book was based on a haori that Kōda designed and gave Aoki as a bridal gift (see figure 10). Here, Aoki plays with the known author-book connection seen in the Kōda gōshi volumes, describing young Rutsuko (as a metaphor for the book Kimono itself) happily going out to town in new clothes (Aoki Tama [1995] Reference Aoki2000, 49). And in another essay, “Usuwata” (Padded kimono), Aoki talks about a dōgi undergarment she had made for her mother's eightieth birthday, directly linking Kōda with Rutsuko by noting how Kōda wore a dōgi in her old age, despite having torn off its sleeve in her youth (206).

Figure 10. The Kimono book cover based on a black haori with sleeves featuring flower-patterned insets that Kōda had made for Aoki (Kōda Reference Kōda1996a).

On the surface, these essays simply appear as memoirs. They can even, from the perspective of literary scholars, seem restrictive or misleading in that they highlight autobiographical elements in Kimono and focus on Kōda through the objects she owned and wore rather than through her language and narratives. Indeed, Aoki's essays have been ignored in the academic context, seen perhaps as little more than light nonfiction featuring objects and family anecdotes. Yet I would argue that these essays play a valuable role in furthering our understanding of Rutsuko's story because they revitalize its core meaning and reproduce a similar educational process. In fact, Aoki's essays reenact successful practices of kimono literacy and replicate Kōda's novelistic tropes of correct, in-depth interpretation. Just as readers learn how to understand what kimonos are saying through Rutsuko's development, they can follow the same process through Aoki's own engagement with the kimonos that have been left to her by her mother.

My analysis here is not a limiting means of interpretation that only reads through a biographical lens, but an attempt to read materially, engaging with literature as a thing that—like a kimono—can be taken apart, reproduced, and consumed in different contexts, and as something with a meaningful afterlife. While acknowledging that Kimono is a work unto itself, I suggest that these later essays complement and add new layers of signification to Kōda's text. Aoki, as well as her own daughter, Aoki Nao, appeared in magazines during this period as kimono advocates and practitioners promoting kimono culture and the legacy of Kōda Aya (see, e.g., Kurowassan tokubetsu henshū: Kimono no jikan 2003, 118–19, 175). Aoki explains that publishers came up with the idea to “turn her into an emonkake (kimono hanger),” someone who could wear and give life to the garments Kōda left behind (Aoki Tama Reference Aoki, Kōda and Tama2009, 243). But despite presenting herself in a self-deprecating manner as a passive “hanger” that simply inherited and wore these items for the media, Aoki engages actively with these objects in her writing, textually performing the ideas in Kimono from a new perspective.

In the essay “Tachikake no yukata” (Half-cut yukata) in Kimono dresser, for example, Aoki goes through her mother's belongings after her death and discovers a cotton kimono fabric only partly cut in preparation for sewing. She is puzzled for a while since she knows her mother regularly made such a kimono in “half a day,” but soon realizes that this object speaks of her mother's decline and perhaps even of her awareness of impending death (Aoki Tama [1995] Reference Aoki2000, 104). Aoki's ability to read kimono in this way is also shown in “Toriaezu no hako” (The “for the moment” box), an essay in Kimono before and after. Rummaging through her mother's box labeled “toriaezu” (for the moment), she discovers rolls of different types of brand-new kimono silks. All are in their original white state (before being dyed, cut, and sewn into garments). Aoki understands this to be Kōda's preparation for unforeseen circumstances, including the loss of such fabric in the future (due to the disappearance of kimono industry experts). Such cloth is also meant as a gift for her inheritors, a kind of blank canvas to be used for their own expression (Aoki Tama [2004–5] Reference Aoki2006, 12–14).

The box is labeled “for the moment” because these kimonos are only in a temporary state and must be completed through human participation. Aoki shows how she builds on these texts/textiles, provided by her mother's foresight. Actively engaging with kimonos in this way, Aoki learns to interpret what each item is saying, and through this intimate communication with objects she begins to articulate her own identity. The white cloth that needs to be designed and dyed is presented as a “difficult question/problem” (nanmon) for which a good answer or solution must be found (Aoki Tama [2004–5] Reference Aoki2006, 14). Just like Rutsuko, who becomes connected to the family past and to other characters through kimonos, Aoki reproduces her own process of being “educated and nurtured” by what her mother has left behind in dressers and boxes.

Aoki's challenge is also to understand her own tastes and to create meaningful objects by remaking and utilizing what is available. By developing relationships with craftspeople and specialists, Aoki transforms a number of fabrics and makes them useful. She takes a kimono that Kōda made in her sixties and has it redyed and redesigned for her own daughter; she transforms a black fabric for formal funeral wear into a casual blue kimono made with a special wax drip technique creating the effect of numerous tiny “stars against the night sky” (Aoki Tama [2004–5] Reference Aoki2006, 40). Presenting kimonos as a means of creativity and transformation also powerfully evokes aspects of Rutsuko's lessons.

Aoki Tama's kimono essays published during the 1990s–2000s can be described as memoirs and photo documentations of kimono culture, but they should also be viewed as valuable literary responses to Kōda Aya's Kimono that uniquely reanimate its content. These works distill the essence of Rutsuko's education, the importance of cultivating in-depth kimono “reading” (interpretation) and “writing” (creative self-expression) for individual growth. By illustrating its continued relevance for new generations of readers, these essays meaningfully contribute to the novel's afterlife.

The Afterlife of Things

Currently, the kimono in Japan continues to be used as high-end formalwear for specific occasions, but at the same time, it has also become more of an accessible product due to the growth in the used kimono market, the development of online sales venues, and an increase in affordable fabrics.Footnote 34 Aoki Tama (Reference Aoki2006, 188) observes in the early twenty-first century that there is an increase in the number of people who wear kimonos. And a 2010 book explains that kimonos used to be worn mainly for established formal events, but now women interested in wearing them actively seek out different social opportunities to do so. Rules about protocol and other practices have loosened, and kimonos have become more approachable; still exotic compared to Western wear, they have also become expressions of unique individuality and tools for “enhancing the self” (jibun migaki) (see Matsubara Reference Matsubara2010, 21–22, 29).

The kimono is still “alive” in Japan, inspiring “mutual feeling” albeit in ways that Kōda did not foresee. This is also true for Kimono, an incomplete work depicting what was considered to be a disappearing object. Every text has a kind of afterlife subsequent to its publication and the death of its author, and it is impossible to completely detail how an unfinished text lives on through other works and subsequent eras. We can say, however, that although the kimono essays by Aoki Tama are not sequels or textual completions in the strict sense, they constitute critical responses and textual overwriting by a literary inheritor. Thus they enhance our broader understanding of Kimono and enable a perspective of Kōda as a literary progenitor in addition to the more established view of her as a literary daughter. Instead of considering Kōda only in reference to her father, Rohan, we can appreciate how certain literary tropes and modes of expression are now carried on by her daughter.

Kōda's granddaughter, Aoki Nao, also continues the family legacy in Kimonos of the Kōda family. Although this 2011 essay collection does not directly mention Kimono, it is clearly in conversation with her grandmother's novel as well as her mother's engagement with it. Like Rutsuko in the novel, Aoki Nao shows the process of becoming an agent who can wear kimonos well, understand what suits her best, remake kimonos in suitable ways, and interpret the world through these objects. The idea of a lifetime of learning through kimonos is recreated in these works, which, in turn, heightens the original lessons in Kimono. Kōda's text is thus infused with new life in contemporary Japan even as the vocabulary, content, and significance of kimono language itself is changing.

By reading Kimono through prewar, postwar, and contemporary timeframes, and by taking it apart like a well-worn item of clothing, we can explore its lifecycle in reinvented forms. This is not a rejection of other approaches to this novel or a suggestion that we must, as early twenty-first-century readers, also read works by Aoki Tama or Aoki Nao in order to understand all of Kōda's writing. Rather, I suggest that by focusing on the social life and afterlife of things, literary scholars can extend the very meaning of a text, as something woven from many strands. By focusing on kimono, the material object at the heart of this particular novel, our eyes are opened to historical contexts as well as possibilities for synchronic and diachronic modes of reading. Kimono features kimonos and is a work enlivened by them, but in a larger sense, it shows the importance of things—their power in creating identity and also presenting interpretive possibilities. By listening to the unexpected stories that things tell, we can explore new and broader questions of literary representation and contextual meaning.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Kim Brandt, Rebecca Copeland, Michael Dylan Foster, and the anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Asian Studies for their valuable comments and suggestions. Thanks also to my family for their support of this project.