No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

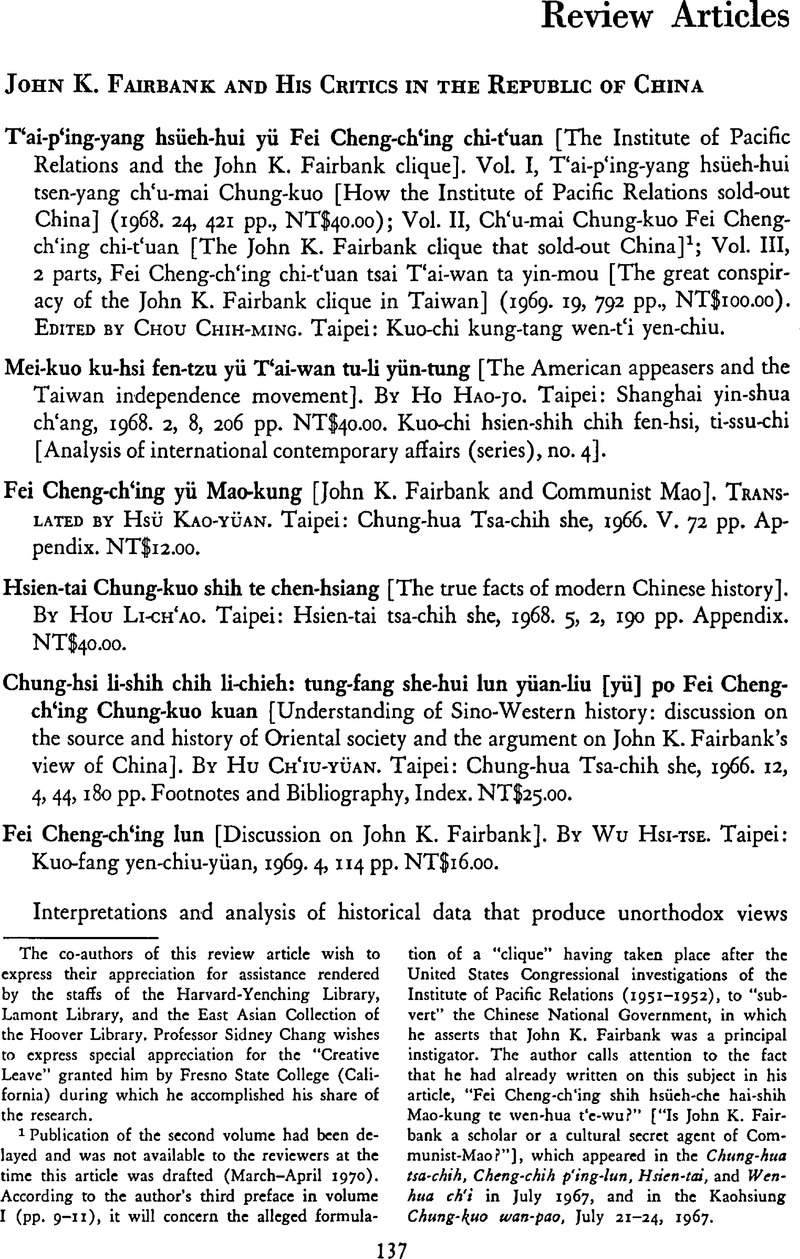

John K. Fairbank and His Critics in the Republic of China

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 March 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1970

References

The co-authors of this review article wish to express their appreciation for assistance rendered by the staffs of the Harvard-Yenching Library, Lamont Library, and the East Asian Collection of the Hoover Library. Professor Sidney Chang wishes to express special appreciation for the “Creative Leave” granted him by Fresno State College (California) during which he accomplished his share of the research.

1 Publication of the second volume had been delayed and was not available to the reviewers at the time this article was drafted (March–April 1970). According to the author's third preface in volume I (pp. 9–11), it will concern the alleged formulation of a “clique” having taken place after the United States Congressional investigations of the Institute of Pacific Relations (1951–1952), to “subvert” the Chinese National Government, in which he asserts that John K. Fairbank was a principal instigator. The author calls attention to the fact that he had already written on this subject in his article, “Fei Cheng-ch'ing shih hsüeh-che hai-shih Mao-kung te wen-hua t'e-wu?” [“Is John K. Fairbank a scholar or a cultural secret agent of Communist-Mao?”], which appeared in the Chung-hua tsa-chih, Cheng-chih p'ing-lun, Hsien-tai, and Wenhua ch'i in 07 1967Google Scholar, and in the Kaohsiung Chung-kuo wan-pao, 07 21–24, 1967.Google Scholar

2 The early objects of criticism were Professor Fairbank's co-authored text, A History of East Asian Civilization (Vol. I, “East Asia: The Great Tradition,” with Edwin O. Reischauer [Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1960]; Vol. II, “East Asia: The Modern Transformation,” with Reischauer and Albert M. Craig [Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1965]) and the Brien McMahon Lecture series, given at the University of Connecticut in 1960.Google Scholar

3 U. S. Senate, 82nd Cong., 2nd Sess., Institute of Pacific Relations: Report of the Committee on the Judiciary … A Resolution Relating to the Internal Security of the United States; Hearings Held July 25, 1951–June 20, 1952 by the Internal Security Subcommittee (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1952). This chapter (no. 2) is a Chinese translation of portions of the Senate's report made by Hu Li-min in Hong Kong in 1953, published under the title Mei-kuo cheng-fu nei te Kung-ch'an-tang (Communists in Government: Report by U. S. Senate Judiciary Committee), [Hsinshih-chi ch'u-pan-she (The New Era Press)]. On another page appears the untranslated subtitle Pang-chu Chung-kung ch'in-to liao Chung-kuo [Helping the Chinese Communists' violent seizure of China]. Hu's footnotes were eliminated and replaced by Chou's footnotes which largely refer to various chapters of his own work. Only a few relatively insignificant paragraphs in the Hu translation were omitted by Chou.

4 Vol. XXXV, No. 13, Section 2 (March 31, 1952), pp. 1–16. Criticism exchanged between Walker, William L. Holland, Secretary General of the IPR, and the journal's editors, appearing in The New Leader, Vol. XXXV, No. 16 (04 21, 1952), pp. 10–12Google Scholar, are not included in Chou's book. The translation, made earlier by Huan P'ing, Lat'ich-mo-erh yü T'ai-p'ing-yang Hsüeh-hui [Lattimore and the Institute of Pacific Relations] (no citation given), omits portions of the original version but does not materially alter the impressions conveyed by the author.

5 The translations, which earlier appeared in the Lien-ho Pao (Taipei), are selected documents from U. S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1941, 7 vols., (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1956)Google Scholar, Vol. V, “The Far East”; and U. S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1943, “China” (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1957).Google Scholar

6 Material on the Marshall mission was taken from Stuart, John Leighton, My Fifty Years in China: The Memoirs of John Leighton Stuart, Missionary and Ambassador (New York: Random House, 1954)Google Scholar, translated by Yen Jen-chün (Jentsun Yen), Tsai Chung-kuo wu-shih-nien, 2 vols., (Hong Kong: Christian Translator's Service, 1955)Google Scholar. The declared object of the editor (pp. 186–187) is to “prove” that the establishment of a coalition government was an American imposed condition for China's receipt of economic and military aid, and hence, “evidence” of American interference in Chinese affairs. The editor further infers that Marshall, and President Harry S. Truman, were affected by the IPR, and the lack of further aid encouraged the Communist cause (p. 198).

7 Selections were taken from Hsien-kuang, Tung, Chiang Tsung-t'ung Chuan [Biography of President Chiang], 3 vols., 3rd ed. (Taipei: Chung-hua wen-hua ch'u-pan shih-yeh wei-yüan-hui, 1954)Google Scholar, a Chinese language edition of Tong, Hollington K., Chiang Kai-shek: Soldier and Statesman (Taipei: China Publishing Co., 1952).Google Scholar

8 (Chicago: H. Regnery, 1963).

9 By General Albert C. Wedemeyer (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1958).

10 This material comes originally from an interview granted to a Scripps-Howard correspondent in Shanghai. In late March 1948, it began to appear in nineteen American newspapers including the New York World Telegram. Chinese translation of the interview began to appear in Shen Pao (Shanghai), 03 24, 1948–04 14, 1948.Google Scholar

11 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1947), taken from pp. 226–229. Chou used a translation made by Mang, Wang et al. , Mei-Su wai-chiao mi-lu [Secret record of American-Soviet relations], 2nd ed., (Naking: Chung-yang hsin-wen she, 1947).Google Scholar

12 Proceedings and Debates, 79th Cong., 1st Sess., Vol. 91, Pt. 13, Appendix, A5528–5531 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1945).Google Scholar

13 The excerpt is from Shao Yü-lin, Sheng-li ch'ien-hou [Before and after victory], (Taipei: Ch'uan-chi wen-hsüeh ch'u-pan-she, 1967), pp. 5–15Google Scholar. Shao, who was educated in Japan and served in the Chinese foreign service there and in Korea and Turkey, was a member of the Chinese delegation to the PR Conference in January, 1945. In this excerpt, he presents, among other things, his version of Communist activities in the IPR.

14 Chou used Yen Jen-chün's translation again but omitted part of it. In Stuart's book, the part excerpted begins at the bottom of page xiv.

15 On the Wen-hsing clique, see Chou, Vol. III, Pt. 1, 238–302, Pt. 2, 503 ff. For perhaps the best reference, see Li-chao, Hou, Wen-hsing chi-t'uan hsiang-tsou na-t'iao lu? [Which way will the Wenhsing clique go?] Taipei, 08 1964, 121Google Scholar p. (Partially reprinted in Chou, Vol. III, Pt. 1, 88–140), and “Fei Cheng-ch'ing yü Wen-hsing chi P'eng Ming-min chih kuan-hsi” [“The relationship of John K. Fairbank with Wen-hsing and P'eng Ming-min”], Hsien-tai, 24 (04 1, 1968), p. 22Google Scholar. For Western reports on this issue, see the London Economist, 04 1, 1968Google Scholar, and The New York. Times, 03 26, 1968Google Scholar. Also see Hu Ch'iu-yüan's reply to the Economist in Chung-hua tsa-chih, V. 6, No. 5 (05 20, 1968), p. 48Google Scholar, also in Chou, Vol. III, Pt. 1, 317–318. For the Chinese Communist view on this issue, see the editorial in Ta-kung pao, 04 23, 1968Google Scholar, “T'ai-wan te Wenhsing shih-chien” [“The Taiwan wen-hsing case”].

16 Yin Hai-kuang, late professor of National Taiwan University (who died September 16, 1969 after a long illness) and author of Lo-chi hsin-yin [New introduction to logic] (Hong Kong: Ya-chou ch'u-pan-she, 1955)Google Scholar and Chung-kuo wen-hua te chan-wang [The outlook for Chinese culture] (2 vols., Taipei: Wen-hsing shu-chü, 1966)Google Scholar, has been considered a highly controversial figure in academic circles in Taiwan due to his critical attitude toward Chinese culture and tradition and other existing problems in Taiwan during recent years. For a good introduction to his ideas, see Ku-ying, Ch'en, Yin Hai-kuang tsui-hou te hua-yü [The last words of Yin Hai-kuang] (Taipei: Shih-chieh Wen-hua Kung-ying-she, 1970)Google Scholar and his own Yin Hai-kuang chin tso hsüan [Selections of Yin Hai-kuang's recent works] (Taipei: Hai-kuang wen-hsüan she, 1969)Google Scholar. Numerous articles appeared about him after his death, mainly in Jen-wu yü ssu-hsiang, a semimonthly in Hong Kong. For other references, see Chan-chi, Huang, “Yin Hai-kuang chiao-shou: i-ke Chung-kuo chih-shih-fen-tzu te pei-chü” [“Professor Yin Hai-kuang: tragedy of a Chinese intellectual”], Min-pao yüeh-k'an, V. 2, No. / (06, 1967), 53–58Google Scholar, also in Chung-hua tsa-chih, V. 5, No. 11 (11 20, 1967), 48–51Google Scholar. For attacks on him, see Li-chao, Hou, “Ch'uan-p'an hsi-hua p'ai te yao-wang: Yin Hai-kuang chih chieh-hsi” [“The young death of the complete westernization faction: the anatomy of Yin Hai-kuang”], Hsientai, No. 19 (11 1, 1967), 14–22Google Scholar, and No. 20 (December 1, 1967), 15–23. Views of Professor Fairbank and eighteen of his associates at Harvard University about Yin were expressed in a telegram of condolence sent to his bereaved wife, dated Sept. 29, 1969. They referred to Professor Yin as “a scholar of critical mind and creative gifts, an exciting teacher, and a man whose devotion to freedom of inquiry and freedom of expression has given us all an inspiring example of intellectual integrity and personal courage.”

17 Of interest is that the Chinese newspaper in Hong Kong, Ta-kung pao, sympathetic to the mainland government, also referred to Fairbank and his associates as “American appeasers.” See editorials in that paper of April 20, 21, 22, 23, 1968.

18 U. S. Senate, 86th Cong., 1st Sess., United States Foreign Policy, Asia, Studies Prepared at the Request of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, by Conlon Associates, Ltd., No. 5, November 1, 1959 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1969). The principal writers of this report were Richard L. Park (South Asia), Guy J. Pauker (Southeast Asia), and Robert A. Scalapino (Northeast Asia), then all at the University of California (Berkeley). Professor Scalapino had written the portion of the report dealing with Communist China and Taiwan, pp. 119–155. Professor Fairbank took no part in the preparation of the study.

19 Dr. Jessup is implicated by Ho as a co-conspirator with Professor Fairbank in giving impetus to the formation of a rival political party, the Chung-kuo tzu-yu tang. This development, in which Hu Shih and Chiang T'ing-fu (T. F. Tsiang) are mentioned as the party's founders, coincided with the preparation of the “China White Paper” [U. S. Department of State, United States Relations With China: With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1949)Google Scholar.] in which Dr. Jessup was principal editor.

20 Ho Hao-jo, basing his information on an article by Li Tung-fang (Orient Lee) in the Chunghua Tsa-chih (Vol. V, No. 11 [11 20, 1967], 8–13, [also in Chou, Vol. III, Pt. 2, 656–671])Google Scholar, claimed that “an annual compensation of US $50,000 was granted to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, from the Ford Foundation fund under his [Fairbank's] control. A condition of exchange was that he would have part of our archives. Since then, John K. Fairbank has used these materials to attack our country” (Ho, p. 8).

21 P'eng Ming-min, a former Professor of Political Science at National Taiwan University, was found guilty of sedition on April 2, 1965 and was sentenced to eight years in prison, from which it was recently reported he had “escaped.” He, and two of his former students, had been charged with the printing and planned distribution of subversive literature advocating the overthrow of the constitution of the Republic of China.

22 The most comprehensive presentation of this issue is in Chou, I. For a poignant summary, see Chou's own preface, pp. 8–24, and Jen Cho-hsüan's preface, pp. 3–4 on the loss of China; also of interest is the review of Chou's volume by Jung-ch'ang, Yang, “‘T'ai-p'ing-yang hsüeh-hui tsen-yang ch'u-mai Chung-kuo’ tu-hou” [“After reading ‘How the Institute of Pacific Relations sold-out China’”], Cheng-chi p'ing-lun, Vol. XXI, No. 9 (01 10, 1969), 28–30Google Scholar. He concludes that Professor Fairbank is a “remnant” of the IPR who is still attempting to sell-out China.

23 Ho Hao-jo refers to a reported incident in which Fairbank was said to have introduced Ch'en I-te, formerly active in the independence movement, as “the future President of the Taiwan Republic.” (In quoting Fairbank, however, Ho rethe ferred to a “P'i-tê Ch'en” (Peter Ch'en), leaving confusion over the proper identity of Ch'en).

24 This document was transmitted by Ambassador C. E. Gauss at Chungking to the U. S. Secretary of State. It was prepared November 19, 1943 by Professor Fairbank who was then in the Chinese capitol as a representative of the Interdepartmental Committee for the Acquisition of Foreign Publications. The subject concerns the student movement and what Professor Fairbank then identified as the “intellectual stultification … promoted largely by Chen Li-fu, the Minister of Education and a leader of the reactionary CC clique.” See U. S. Foreign Relations, 1943, “China,” pp. 384–385Google Scholar; also reproduced in Ho, pp. 12–13.

25 Rev. ed. (New York: The Viking Press, 1962), pp. 47–50, 51–54, 72, 102–105, 294–296.

26 Volume I of A History of East Asian Civilization (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1960), 670.Google Scholar

27 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), pp. 204–205.

28 “The People's Middle Kingdom: Sinocentrism in Modern Dress,” Vol. 44, No. 4 (07, 1966), pp. 574–586.Google Scholar

29 The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 178, No. 3 (09, 1946), 37–42Google Scholar. Hou used the title “Chung-kuo shih-chü chen-hsiang” [“The true picture of conditions in China”]. The translation had appeared in the Shanghai Hsin-min wan-pao, 09 29, 1946.Google Scholar

30 Encounter, Vol. XXVII, No. 6 (12 1966), 14–20Google Scholar. The reply made by Ch'iu Hung-ta first appeared in the Hong Kong Ming-pao yüeh-k'an, Vol. II, No. 5 (05, 1967), 14–15.Google Scholar

31 The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 217, No. 6 (06, 1966), 77–85Google Scholar. Liang's criticism was originally printed in Cheng-hsin hsin-wen, 06 28, 08 2, 1966.Google Scholar

32 “Mao Tse-tung chu-i te ken-yüan yü Chung-kuo wen-hua chih kuan-hsi” [“The origin of Mao Tse-tungism and its relation to Chinese culture”] pp. 81–103), and “Fei Cheng-ch'ing te cheng-chih mien-hsiang chi cheng-chih yün-tso” [“The political framework and political tactics of John K. Fairbank”] (pp. 105–124).

33 This is an old issue, once having been the subject of some controversy in the United States. See Wittfogel, Karl A., “The Legend of ‘Maoism’” Part I), The China Quarterly, No. 1 (01–03, 1960), 72–86Google Scholar; Part 2, The China Quarterly, No. 2 04–06, 1960), 16–34Google Scholar, also Schwartz, Benjamin, “The Legend of the ‘Legend of “Maoism”’,” 35–42Google Scholar; Wittfogel, Schwartz, Henryk Sjaardema, “‘Maoism’—‘Legend’ or ‘Legend of a “Legend”’?” The China Quarterly, No. 4 (10–12 1960), 88–101.Google Scholar

34 Chou Chih-ming went further and declared that “both John K. Fairbank and his wife are American Communists.” See Chou, , I, 13Google Scholar; also, Hsüeh-chia, Cheng, “Fei Cheng-ch'ing shih Kung-ch'an-tang” [“John K. Fairbank is a Communist”], Hsien-tai, No. 25 (05 1, 1968), p. 20Google Scholar. Ho Hao-jo (cited in Chou's books) also regarded Fairbank as a Communist sympathizer and placed weight in support of his argument on a speech critical of Fairbank's advice on China made by John F. Kennedy in 1949 that was reprinted in the Congressional Record in 1961; see Chou, Vol. III, Pt. 1, 25; Pt. 2, p. 333; United States, Congressional Record, 02 21, 1949, p. A993, 08 23, 1961, pp. A6655–A6656.Google Scholar

35 Hu had already published most of his critique in serial form; see “P'ing Ha-fu Fei Cheng-ch'ing chiao-shou chih Chung-kuo kuan” [“Remarks on Harvard Professor John F. Fairbank's views of China”], Chung-hua tsa-chih, Vol. II, No. 10 (09 17, 1964), 5–10Google Scholar; No. 11 (November 17, 1964), 12–24, 27; No. 13 (December 17, 1964), 12–34.

36 For a brief discussion of this matter, see Fairbank, John K., The United Slates and China, 2nd ed., (New York: The Viking Press, 1958), pp. 56–58, 102–105.Google Scholar

37 The writer is Liang Ho-chün, whose article “Fei Cheng-ch'ing yü Chung-kung [“John K. Fairbank and the Chinese Communists”], Cheng-hsin hsin-wen, 06 28 and 08 2, 1966Google Scholar, is reproduced in Hou's book. Liang cites as evidence that Fairbank “thoroughly opposed Confucianism” the memorandum of Ambassador C. E. Gauss written on Nov. 19, 1943 and published in U. S. Foreign Relations, 1943, “China,” p. 385.Google Scholar

38 Professor Fairbank has written much about the need to attempt to measure the degree of “Chineseness” discernible in Communist China. For a brief summary, see his The United States and china pp. 307–317, especially pp. 313–314.Google Scholar

39 For a full discussion of this subject, Hou Li ch'ao's chapter entitled “Mao Tse-tung chu-i te ken-yüan yü Chung-kuo wen-hua chih kuan-hsi” [“The relationship of the origin of Mao-tse-tungism with Chinese Culture”], Hou, , pp. 81–103.Google Scholar

40 An interesting discourse on Synarchy took the form of a letter written to Professor Fairbank by Ch'en Ch'i-t'ien, Aug. 22, 1958, published in Hou, pp. 39–43. For additional views on Western demands for special privileges, see Ch'iu Hung-ta, “Tui Fei Cheng-ch'ing te ‘Chung-kuo shih-chieh Chih-hsü’ kuan te chi-tien i-chien” [“Several opinions with regard to John K. Fairbank's ‘China's World Order’”], Ming-pao yüeh-k'an (Hong Kong), Vol. II, No. 5 (05, 1967), 14–15Google Scholar; also in Hou, , pp. 57–60.Google Scholar

41 See Fairbank's “Synarchy under the Treaties,” in his Chinese Thought and Institutions (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), pp. 204–231Google Scholar; also Fairbank's “The Early Treaty System in the Chinese World Order,” in his The Chinese World Order: Traditional China's Foreign Relations (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968), pp. 257–275Google Scholar. Fairbank first coined the phrase “synarchy” in 1953; see his Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1953), p. 465.Google Scholar

42 Wu Hsi-tse questions Fairbank's reliance on the Hai-lu (A maritime record) to which he reions ferred in his Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast, pp. 18–19Google Scholar, China's Response to the West: a documentary survey, 1839–1923 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1954), p. 20Google Scholar, and East Asia: The Modern Transformation, pp. 127–128Google Scholar. Wu regards it as “a small pamphlet … not more than 20,000 Chinese characters” containing numerour errors (Wu, pp. 84–87). He also regards it as “shocking” to learn that Fairbank claimed that Wei Yüan's Hai-kuo t'u-chih (Illustrated gazeteer of the overseas countries) was based on the Hai-lu. According to Wu, those who reprinted the Hai-lu used Wei Yüan's name simply to give it prestige (Wu, , pp. 87–90).Google Scholar

43 Li Tung-fang (Orient Lee) was the most vituperative in his criticism stating, in English, that Fairbank “is practically illiterate in the strict discipline of historical research” and that “he never has read a history of China written in Chinese, or any historical document written in Chinese.” Moreover, in declaring that Fairbank's books and articles are devoid of either hypothesis or evidence, Li said, “In the place of hypotheses, we find only conclusions. In the place of evidence and proofs, we find only dogmas. Fairbank never cares to mention upon what documents or history books his conclusions are based.” Finally, he wrote, “He simply is a faker.” See Li's “Fei Cheng-ch'ing ju-ho ch'ü-chieh Chung-kuo li-shih (shang)” (“John K. Fair-bank, Twister of Chinese History [part 1]),” Chung-mei yüeh-k'an, Vol. XIII, No. 6 (06 1968), pp. 3–4Google Scholar; English version, pp. 4–6.

44 During World War II, many nationalistic histories were written in China, such as Ch'ien Mu's Kuo-shih ta-kang [General outline of the national history]; see Ssu-yü, Teng, “Chinese Historiography in the Last 50 Years,” Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol. VIII, No. 2 (02 1949), p. 146.Google Scholar

45 Shou, Wen, “T'an li-shih chiao-hsuch” [“On history teaching”], Chung-yang jih-pao (Taipei), 08 9, 1969Google Scholar, See also Hu, , p. 11.Google Scholar

46 Ta-nien, Liu, “How to Appraise the History of Asia,” in Feuerwerker, Albert (ed.), History in Communist China (Cambridge, Mass.: The M.I.T. Press, 1968), p. 357.Google Scholar

47 Since neither reviewer is conversant in Russian, we have relied on “An Unauthorized Digest” of Bereznii, L. A., A Critique of American Bourgeois Historiography on China: Problems of Social Development in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (Leningrad: Leningrad University, 1968)Google Scholar, prepared by Mrs. Ellen Widmer for the East Asian Research Center, Harvard University.

48 Since 1946, Professor Fairbank has held no government positions. Although he participated in a State Department Advisory Council on China during the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, it met very infrequently and was not considered instrumental in policy formulation.

49 Expression of concern over the Fairbank influence in Taiwan is frequent, and recommendations are made to counteract it; see Chou, I, 6, 13, 15, 18–23; Ho, 1–9; Wu, 17. For examples of specific commentary on some men noted in this paragraph, see Chou, III, Pt. 2, 373–374, 376–377 (on Wang), 345–346, 361 (on Kuo), 393–397. 451–452 (on Li), 335–336 (on Hu), 454–457 (on Ho).

50 The late Ch'ing censor, Ch'u Ch'eng-po, resisted any displacement of Chinese values, and Yeh Te-hui defended both the Confucian Way and traditional institutions. See deBary, Wm. Theodore, Chan, Wing-tsit, Watson, Burton, Sources of Chinese Tradition (New York; Columbia University Press, 1960), pp. 736–738, 741–743.Google Scholar