Introduction

The recent democratic backsliding (Lührmann and Lindberg, Reference Lührmannm and Lindberg2019) necessitates a re-assessment of the linkage between party systems and democracy. The dictum of the classical political development literature was that the institutionalization of party systems and the consolidation of democracy are practically the same thing. Ever since, it is often assumed that stable party systems ‘increase democratic governability and legitimacy by facilitating legislative support for government policies; by channeling demands and conflicts through established procedures; by reducing the scope for populist demagogues to win power; and by making the democratic process more inclusive, accessible, representative, and effective’ (Diamond, Reference Diamond, Diamond, Platter, Chu and Dien1997: xxiii).

Today political parties are central political institutions and competitive elections are a must in most countries around the globe, and yet, hybrid regimes and defective democracies proliferate. Incumbent illiberal politicians systematically undermine the separation of powers, the rule of law, the neutrality of the state, and the constraints on the executive – the characteristics that make a democracy liberal. As Diamond put it, ‘the gap between electoral and liberal democracy has grown markedly during the latter part of the third wave’ (Reference Diamond1999: 10). While Zakaria's (Reference Zakaria2003) much cited claim that in today's world democracy is flourishing, liberty is not, can be criticized for not sufficiently recognizing that liberty is a precondition for democratic order, the suggestion that the development of liberal democratic structures may differ from the trajectory of popular and electoral democratic structures is well justified.

Even if institutionalized party politics is beneficial for the overall level of democracy, the impact of institutionalized party politics on liberal democratic aspects requires a scrutiny on its own. On the one hand, the predictability associated with the institutionalized interaction of a few, continuously existing parties is likely to protect the nation against both chaos and the arbitrary rule of charismatic anti-party leaders. On the other hand, the concentration of executive and legislative power in the hands of a few, long-standing political parties may lead to the marginalization of civil society actors, minorities, and smaller parties, making the regime unresponsive to new demands and hurting the individual rights of citizens. Therefore, there are reasons to suspect a complex relationship between institutionalized party politics and the liberal dimension of democracy.

We will approach the institutionalization of party politics by applying the conceptual and operational tools of party system closure (Mair, Reference Mair1997; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2016, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021). Closure constitutes a specific aspect of the broader concept of party system institutionalization. Just like the latter, it taps the predictability of party systems, but it singles out party relations in the governmental arena as the crucial site of institutionalization. The empirical basis for calculating the closure index is provided by the party composition of governments. The index has three components: the degree of access of new parties to government, the alternation of government parties from one government to the next, and the familiarity of coalition formulae. The dataset (cf. Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2022) covers 58 European party systems across more than a century. In this regard it constitutes the most diverse empirical basis used so far for testing the relationship between democracy and party system institutionalization. For the assessment of the levels of liberal democracy, we rely on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (version 11.1) (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Krusell, Luhrmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2021; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2021).

The goal is to reach robust conclusions about the linkage between institutionalized party politics and the liberal dimension of democracy by (1) improving on the conceptualization and operationalization of the analyzed phenomena, (2) including more cases, and (3) extending the studied time-spans. We expect party system closure to strengthen liberalism in democracy, particularly as far as its ‘access’ and ‘formula’ components are considered. If the range of governing parties and coalition combinations remains stable and predictable, the liberal aspects of democracy will benefit. However, we hypothesize that the third component of closure, ‘alternation’, will have a negative impact – when parties do not alter in government or when there is complete turnover, the risks for the abuse of power or policy overhaul increase.

The article starts with outlining the overall relationship between party system institutionalization, on the one hand, and democracy, particularly the liberal dimension of democracy, on the other. We then explain how the closure and the liberal democratic nature of party systems are measured. After giving an overview of the dataset compiled for this analysis, we present the results of regression models that probe into the association between liberalism, democracy, and closure as well as the three components of the latter: formula, access, and alternation.

Our analysis shows that liberal democracy is hurt when the governmental arena is closed to newcomer parties, and it gains strength when governments are built around familiar coalitions – but also when incumbents decide to coopt parties from the opposition. Taken together, these results mean that party system closure as a whole shows no significant impact on the liberal dimension of democracy, because its different components cancel each other out. Since two of the three components of closure have a negative relationship with liberal democracy, the excessively optimistic assessments of the benefits of institutionalized party politics in general need revision. We end with a discussion of what this entails for contemporary party systems and how it helps us to better understand the erosion of liberalism in democracy.

The uneasy relationship between party system institutionalization, democracy, and liberalism

On the one hand, previous research provides grounds to expect a positive association between party system institutionalization and democracy. The former is supposed to reduce the scope of populist leaders, and to promote accountability (Birch, Reference Birch2003; Schleiter and Voznaya, Reference Schleiter and Voznaya2018), governability (Diamond and Linz, Reference Diamond, Linz, Diamond, Hartlyn, Linz and Lipset1989; Mainwaring et al., Reference Mainwaring, O'Donnell, Valenzuela, Mainwaring, O'Donnell and Valenzuela1992; Innes, Reference Innes2002; Zielinski et al., Reference Zielinski, Slomczynski and Shabad2005; Thames and Robbins, Reference Thames and Robbins2007), programmatic representation (Mainwaring and Torcal, Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and Crotty2006), and legitimacy (Mainwaring and Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Diamond, Reference Diamond, Diamond, Platter, Chu and Dien1997: xxiii). On a more general level, low institutionalization can prevent both parties as well as voters from engaging in strategically driven coordination (Mainwaring and Zoco, Reference Mainwaring and Zoco2007), intensifying problems of collective action in relation to preference aggregation.

In party systems that follow no established patterns of behavior and produce ad hoc governments, it could be the case that patronage is the only factor that keeps coalitions together (Lewis, Reference Lewis2006; O'Dwyer, Reference O'Dwyer2006). The governments of inchoate party systems tend to be short-lived (Powell, Reference Powell1982; Müller-Rommel et al., Reference Müller-Rommel, Fettelschoss and Harfst2004; Baylis, Reference Baylis2007; Savage, Reference Savage2016) and therefore the policymaking process can be of low quality. An enduring set of actors and institutional continuity is a prerequisite for successful economic and administrative reforms (Dimitrov et al., Reference Dimitrov, Goetz and Wollmann2006; Tommasi, Reference Tommasi2006; O'Dwyer and Kovalcik, Reference O'Dwyer and Kovalcik2007). It is easier for political actors to determine which party suits them best in the case when governments are composed of a narrow range of parties, which have stable associations amongst each other. Under such circumstances voters are in a position to form a connection to specific political groups, which can extend into loyalty to the political system, further strengthening the latter's legitimacy and stability (Dalton and Weldon, Reference Dalton and Weldon2007).

Stability in the range of alternative governments provides political actors with a broader time span and makes democratic competition more predictable and thus is one of the fundamental reasons why the consolidation of party relations in government can improve democracy. The sources of continuity and predictability can be diverse, including institutional, cultural, demographic, etc., factors. While the literature tends to emphasize the close relationship between parties and specific social groups as the anchor of this stability (Pridham, Reference Pridham1990; Mainwaring and Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Morlino, Reference Morlino1998; Tavits, Reference Tavits2005; Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2017), the degree of closure is also a function of the internal norms of a country's party politics.

It is not uncommon that democratic erosion and failure takes place when a leader emerges, who gathers the reins of power and creates a gap between the demos and its democratic institutions (parties or parliaments). This is less likely in closed systems, where ambitious political entrepreneurs are incentivized to join existing forces, respect established institutions, advocate incremental changes, and remain within the boundaries of liberal, representative democracy (Lane and Ersson, Reference Lane and Ersson2007). It is easier to cultivate complex programmatic traditions and to lock in voters and politicians into such traditions if the roster of parties and the relations among parties is stable (Kitschelt et al., Reference Kitschelt, Hawkins, Luna, Rosas and Zechmeister2010). In the absence of such stability, political actors are more likely to resort to material incentives or charismatic appeal.

On the other hand, there are also arguments that cast doubt on the claim that party system institutionalization is an unconditional blessing. Scholars ranging from Ostrogorski (Reference Ostrogorski1902) to some of the very recent democratic theorists (cf. Saward, Reference Saward2001) have criticized democratic politics for being party-centered. Democracies that revolve around parties can easily turn into oligarchic systems of partial, bureaucratic, and elitist organizations, especially if other political agents like trade unions or mass movements are sidelined. This is especially the case if the range of governing parties is limited to old and established parties and if patterns of coalition formation do not adopt to changing circumstances.

Moreover, the danger that the state is captured by actors that have concentrated power is particularly high in closed systems (Meyer-Sahling and Veen, Reference Meyer-Sahling and Veen2012). Those in power have an incentive to warp the activities of the state to their benefit and as such constitute a threat to the rule of law and a political equality. To the extent that high closure results from an antagonistic relationship between two parties or two blocks of parties, it is less appropriate to speak of an oligarchy. But as far as the preconditions of a consolidated democracy are concerned, the situation may be even worse: the high polarization associated with such configurations is likely to undermine mutual respect, rational decision-making, and trust in the system.

In terms of the empirical co-variation of the various measures of democracy and of institutionalized party politics, most studies (e.g. Diamond and Linz, Reference Diamond, Linz, Diamond, Hartlyn, Linz and Lipset1989; Mainwaring and Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Morlino, Reference Morlino1998; Kuenzi and Lambright, Reference Kuenzi and Lambright2005; Tavits, Reference Tavits2005; Hicken, Reference Hicken2006; Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2007; Weghorst and Bernhard, Reference Weghorst and Bernhard2014; Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2017) point to a positive pattern, finding frequently changing party labels and unpredictable relations among parties in the least democratic systems. But quite a few studies (e.g. Schedler, Reference Schedler1995; Tóka, Reference Tóka1997; Stockton, Reference Stockton2001; Wallis, Reference Wallis2003; Basedau, Reference Basedau, Basedau, Erdmann and Mehler2007; Thames and Robbins, Reference Thames and Robbins2007) found evidence to the contrary, and even Mainwaring and Scully (Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995: 22) arrived to the qualified conclusion according to which the exact degree of party system institutionalization may be irrelevant above a certain threshold.

Party system closure has been conceptualized (Mair, Reference Mair1997) as a synthesis of three aspects of party relations in the governmental arena: high barriers in front of newcomers (‘access’), a deep divide between government and opposition parties, excluding the possibility that (some) opposition parties join (some of) the incumbents in government (‘alternation’), and the repetition of the familiar coalitions (‘formula’). There are reasons to suspect that these three components may not have a uniform relationship with the liberal dimension of democracy.

As far as access is concerned, the literature provides reasons to regard too much openness as dangerous for democracy. Easy access to government can open the doors of executive power to political outsiders and populist, irresponsible, and illiberal parties. High turnover can lead to a ‘carpe diem syndrome’: new parties may act according to their short-term particular interests and with little respect toward the law. In contrast, the restriction of the governments to a few, well-known players can help the voters to identify accountable parties and under the conditions of high-level electoral accountability parties may refrain from undermining the rule of law. Therefore, while the permanent exclusion of newcomers from government may ossify a political system, our hypothesis is that higher closure on access (i.e. small weight of new parties in governments) has a positive impact on the liberal dimension of democracy.

The second component of party system closure, alternation, is likely to point in the opposite direction. A party system has a high score on this dimension if elections are followed either by the endorsement of the ruling government, with each party remaining in power, or by wholesale alternation, when all parties are replaced. Arguably, party systems that follow this simple, transparent pattern of succession can be considered as more institutionalized or, using Mair's terminology, as closed. But while these configurations help closure, they may undermine liberal democracy. In the first instance, when the same parties dominate the executive, the incumbents develop a monopoly over governing and policymaking, opening the door for the abuse of power. In case of wholesale alternation, governments may be tempted to undo what the previous governments have enacted, weakening the predictability associated with the rule of law.

Wholesale alternation is most typical in contexts when governments composed of one or two parties have a comfortable majority in the legislatures. In such situations the governing parties may consider themselves legitimized to try to dominate the judiciary and to turn the parliament into a rubber stamp legislature, diminishing the control potential of opposition parties. In both cases, there is little incentive for self-limitation, for ‘reaching across the aisle’, and the majoritarian attitude may spill over easily into restrictions on counter-majoritarian institutions. Therefore, we expect that (higher closure on) alternation will have a negative impact on the liberal dimension of democracy.

Finally, the influence of formula (i.e. the frequent re-occurrence of familiar coalitions) may be complicated. On the one hand, when new coalition combinations emerge, there is more political bargaining going on, allowing minority interests to play a more prominent role. Furthermore, in innovative coalitions the partners are likely to share some ideological preferences but not others. As a result, they may need to look for compromise and to subject themselves to the legislature. The judiciary may be more independent, less under the influence of one particular party. Given their unstable composition, governments with innovative formulae will have more difficulties in passing big legislative (e.g. constitutional) reforms that could undermine legal and political traditions.

On the other hand, constant experimentation with new formulae may indicate a lack of consolidation of the democratic regime. In case a completely new party takes over the executive, previous agreements are less likely to be respected. Consequently, and given the heavy emphasis in the state-of-the-art on the importance of some regularity in the political landscape for democratic development, we hypothesize that (high closure on) formula will have a positive impact on the liberal dimension of democracy, acknowledging, however, the mechanisms that may point into the opposite direction.

In order to establish the unique contribution of the discussed phenomena to liberalism and democracy, we need to filter out the effects of potential confounding factors. Party systems tend to be high on closure when they are rich, old, characterized by low degree of electoral volatility, low level of polarization, and low fragmentation (Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021). These conditions may be beneficial for high-quality democracy too, and therefore their contribution to liberalism and democracy must be isolated. As far as the impact of the regime type (presidentialism, semi-presidentialism, or parliamentary regime) is concerned, there is no consensus, but given the importance attributed in the literature to the constitutional framework, we add this factor to the list of control variables. We also control for time (the age of the party system) as democracy and especially the liberal dimension of democracy requires time to consolidate.

Because party system closure is measured through the composition of the governments, it primarily taps the stability of the configuration of parties and political elites and tells us less about electoral dynamics. Therefore, we expect closure to play a more significant causal role in shaping the liberal aspects of democracy than to influence its electoral components. In the subsequent analyses we include both generic measures of democracy and an index that specifically focuses on the liberal components in order to separate the two potential relationships.

Our investigation complements Casal Bértoa and Enyedi's analysis (Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021). In their book they found that the survival of democratic systems is conditioned on high degree of closure, but the association between the quality of democracy and closure depends on economic development: in rich societies they are positively related, in poorer countries there seems to be a negative association. In the current article we go beyond the overall index of closure and consider its individual components and their relations to the indexes of liberal democracy.

Measuring party system closure and liberal democracy

Party system institutionalization as closure in the governmental arena

Party systems have many features and all of them can be more or less stable, but most measures of institutionalization of party politics (e.g. Mainwaring and Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Randall and Svåsand, Reference Randall and Svåsand2002; Mainwaring and Torcal, Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and Crotty2006) focus on electoral volatility, fragmentation, or the age of parties. This practice neglects the governmental arena, even though competition for government can be considered to be the ‘fundamental core’ and ‘the most important aspect of party systems’ (Rokkan, Reference Rokkan1970; Smith, Reference Smith1989; Mair, Reference Mair1997: 206). Furthermore, this practice is insensitive to the most essential feature of party systems: party interactions. If a party system is ‘the system of interactions resulting from inter-party competition’ (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976: 44), then the researchers of party system institutionalization need to analyze the continuity in party interactions across time (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976: 43). In line with the Sartorian approach, we understand party system institutionalization as the process by which the patterns of interaction among political parties become routine, predictable, and stable over time. The way we measure interactions has an important limitation: we only explore the governmental arena. But the closure index has a decisive advantage over other indices of party system institutionalization: it reflects the relations among parties directly.

Party systems are considered to be open when (1) the alternations of governments tend to be partial, (2) no stable configuration of governing alternatives exists (the coalition formulae are unfamiliar), and (3) access to government is frequently granted to parties that have not been in government before. Party system closure is high when (1) alternations of governments are wholesale or if the party composition of governments does not change, (2) the governing alternatives (the party compositions of governments) are stable over a longer extent of time (they are ‘familiar’), and (3) governments are limited to a narrow range of parties. Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2016) operationalized all the three components of closure – alternation, formula, and access – using the percentage of minister changes. This study adopts their operationalization.

Accordingly, the measure of alternation is based on the sum of the differences in ministerial shares of parties in two consecutive governments (equivalent to total net change in the calculation of electoral volatility, see Pedersen, Reference Pedersen1979). Peter Mair associated closure with no or wholesale alternation in government, although he acknowledged that institutionalized party politics can also develop under some predictable form of partial alternation (Mair, Reference Mair1997: 212). Wholesale alternation goes against the principle of closure only if the old government is replaced by entirely new parties, but this rarely happens, and such a development automatically leads to low closure scores due to the decline of scores on formula and access. Party systems where the total change in the shares of ministers belonging to particular parties approaches its minimum (0) or maximum (200) values are thus considered to be closed. Values approaching the center of the scale (100) indicate open party systems. Situations where everything or nothing changes between two governments are both more stable and more predictable than situations where change is partial. Therefore, to obtain the alternation score, one needs to subtract total change (0–200) from 100 and take the absolute value of the result. Cases when there is a change in the distribution of ministers across the participating partiesFootnote 1 but no change in the party composition of government are regarded as instances of maximum closure.

The coalition formula facet of party system closure measures the familiarity or innovation with regard to the combination of parties that govern. The parties in government are evaluated against all party combinations that have occurred during the history of the particular party system and are compared to the government with which there is most overlap in terms of the number of parties.Footnote 2 If the very same combination of parties has already governed together, the closure score of the government formula component is 100. If the government is based on an entirely new combination of parties, then closure is 0. In the rest of the cases the following rules are followed. If a government contains a familiar combination of parties, but also parties that are new to this combination, then the value for closure is the proportion of ministers within the current government coming from the familiar part of the coalition. If one or more parties have left the government (and thus the whole coalition has been in government before, but with additional parties), the value for formula is the proportion of ministers in that previous government coming from parties currently in government. According to these rules, a single party government receives 0 on closure if that party has not been in government before. When such a party has been a member of a coalition in the past, the percentage of its coalition partners is subtracted from 100 to obtain the closure value for formula.

Access is measured as the proportion of ministers in a government that come from parties that have been in government before. It thus indicates how the range of governing parties is changing. Access as a facet of closure is lowest if a government is made up of parties that have not been in government and is highest if a government is formed of parties all of which have been previously in government.

The composite closure index, to which we simply refer as ‘closure’, is calculated as the average of the three components. The raw data for the closure index are in terms of government changes (for how government changes are conceptualized and how different kinds of coalitions are considered, see Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021). In order to arrive at overall measures of closure for party systems, we first extend our government-based data to the level of years as follows. For such years when there was one or several government changes, the closure value is the average of all governments during the year. When no change in government happens, the value of closure for the year is 100. This means that if governments do not change in a specific period, then the closure score for that period is at its maximum value. For those years that had only technocratic, acting, caretaker, etc., governments, we consider yearly closure data as missing. In the following analyses we will characterize the degree of closure of particular party systems by averaging such yearly values across the entire duration of the party system.

Democracy, liberal democracy, and their measurement

Democracy factors into our analysis in two ways. First, the Polity IV index is used to determine the duration of democratic phases in party systems, and thereby the scope of information that can be taken into account to calculate closure. Only systems that score at least 6 on the Polity IV scale that runs from −10 (full autocracy) to 10 (full democracy) are considered. Second, the various democracy indicators of the V-Dem dataset version 11.1 (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Krusell, Luhrmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2021; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2021) are used to evaluate the level of liberal democracy in a democratic party system.

The Polity IV index measures democracy through institutions and procedures that are necessary for citizens to express their political preferences and through constraints on the power of the executive (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). More specifically, it focusses on how competitive the process of filling the executive branch of government is and how much the behavior of the executive is constrained by other political institutions. A country is democratic according to the Polity IV index if positions in government are determined through open and competitive elections (two or more parties or candidates) that are stable (enduring actors compete for power without coercion and no major actor is excluded) and if there are checks and balances on the power of the executive (e.g. legislative power is held by the legislature, which can hold the executive accountable). The threshold for being included in the current dataset is much lower than the maximum fulfilment of these criteria. We can thus presume that all countries in the dataset exhibit a minimum level of open political competition and democratic control over the power of the executive, while there is much room for variation, which can be captured by the more fine-grained indicators of V-Dem.

The V-Dem dataset (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016) goes beyond Polity IV in measuring various aspects of democracy, including liberal democracy. The index for the latter (v2x_libdem) is composed of the electoral democracy index (v2x_polyarchy), which primarily focusses on political competition and free and fair elections, and the liberal component (v2x_liberal), which aggregates indicators of liberalism that are separate from electoral democracy. The liberal component index measures the protection of the rights of individuals and minorities vis-a-vis the state and other limits on the power of the executive (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016: 582–583). It contains three sub-indices, which altogether measure 23 possible specific manifestations of liberal democracy through expert assessment (for more on how the indices are constructed, see Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016). The overall measure of liberalism as well as the subindices is presented on a 0–1 scale, where higher values indicate a better condition of liberalism.

The first sub-index, equality before the law and individual liberty index (v2xcl_rol), which will be called the rule of law index for short, is the most extensive of the three. It is based on 14 indicators that measure the impartiality of public administration, laws and law enforcement, access to justice, property rights, freedom from torture, political killings and forced labor, freedom of religion and of foreign and domestic movement. The second sub-index of the liberalism component, the judicial constraints on the executive index (v2x_jucon), measures how much the executive respects the constitution and the decisions of the courts as well as the independent capacity of the judiciary to act. The third sub-index of liberalism, legislative constraints on the executive index (v2xlg_legcon), measures how much the power of the executive is checked by the legislature or other government agencies and how much the opposition in the legislature has the power to exercise oversight. In order to calculate the liberal component index, the V-Dem dataset takes the average of the three above introduced indices.

Our analysis will use the overall liberalism index as well as the three sub-components as outcome variables. In addition to analyzing the relationship between closure (and the components of closure) and the liberal component of democracy, we also test their association to the electoral component and to the overall index of liberal democracy.

Dataset on party systems

Below we analyze 58 minimally democratic party systems (see Table 1) that existed between 1848 and 2021 in Europe. The original party system closure dataset (Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2022) contained more cases, but we had to leave out Andorra, San Marino, and Lichtenstein as they are not part of the V-Dem dataset, and we had to drop Armenia (1991–1994), the post-WWII party system in Greece (1946–1948), and the Yugoslav Kingdom (1921) as there is no available data on volatility for these cases.Footnote 3

Table 1. Party systems included in the analysis

a Party systems still existing at the time of analysis.

While the utilized dataset is the largest in the field of party system institutionalization studies in terms of time-span and the number of systems included, it is limited to Europe.Footnote 4 At the same time, the dataset includes cases from both Eastern and Western Europe, and therefore contains considerable variation on many relevant political and economic dimensions. Additionally, the coalition politics that is in the focus of our analysis is particularly relevant for the multiparty systems typical of European states.

The units of analysis are party systems; the relevant indicators of closure and liberal democracy are averaged over the whole duration of a party system. Such a high degree of aggregation comes with a great deal of information loss, but it is necessary for two reasons. First, the very concept of party system carries the implication that the logic of party interactions has some resilient, system-specific characteristics. For example, the effective number of parties or the durability of governments is, to a large extent, determined by the institutional environment, most notably the electoral system (see Taagepera, Reference Taagepera2007), which tends to be stable over time. Second, the V-Dem indicators that are used in this paper to measure liberal democracy and its components change on average very little over time within party systems. The correlation between the liberal component at year t and t–1 is 0.95. Considering both party system features and the features of democracy, we see much more variation between systems than within systems. The alternative strategy of analyzing the yearly dataset as panel data, focusing on associations within party systems over time and employing some of the standard Time-series Cross-section (TSCS) methods (e.g. Beck and Katz, Reference Beck and Katz2011), would be problematic in this case given the lack of variation within systems (cf. Plümper and Troeger, Reference Plümper and Troeger2019).

Typically, one country is one party system, but in many instances (see Table 1), there was such a degree of discontinuity in party politics that we had to label the subsequent time-periods as separate party systems. In most cases the decision of where to draw the dividing line is unproblematic (like in the case of Latvia I and Latvia II, divided by 60 years of non-democratic rule) and few additional divisions in comparison to the ones that we have implemented seem justifiable. Nevertheless, we have ran several robustness checks. Most importantly, we reran the regressions taking the ruptures in 1994 in Italy, in 1977 in Belgium, in 1990 in Germany, in 1902 in France, in 2004 in Ukraine, in 1971 in Turkey, in 1917 in Spain, in 2001 in North Macedonia, and in 1909 in Greece as separating distinct party systems. This raised the number of cases from 58 to 67. The results remained essentially the same.

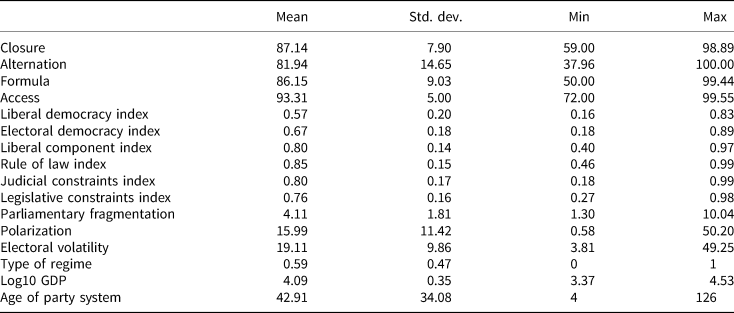

In the subsequent models we control for a host of potentially confounding factors: fragmentation, polarization, electoral volatility, the type of regime, the level of economic development, and the age of the party system. Fragmentation is measured through the effective number of parliamentary parties (Laakso and Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), the standard measure of party system fragmentation. Polarization is captured through the proportion of electoral support for anti-political-establishment parties within the legislature.Footnote 5 As far as electoral volatility is concerned, we use the standard index proposed by Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1979). The type of regime is recorded on a binary scale where 0 indicates presidentialism or semi-presidentialism and 1 signifies parliamentarianism. For the level of economic development, we use the logarithm of per capita GDP from the Gapminder (2021) dataset. Finally, we also include the number of years from the start of the system until its end (or until the present moment) to control for the varying durations of party systems. Like the main variables of interest, the control variables (except age) are also averaged over the lifetime of a party system. Descriptive statistics of all variables included in the models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Analysis and results

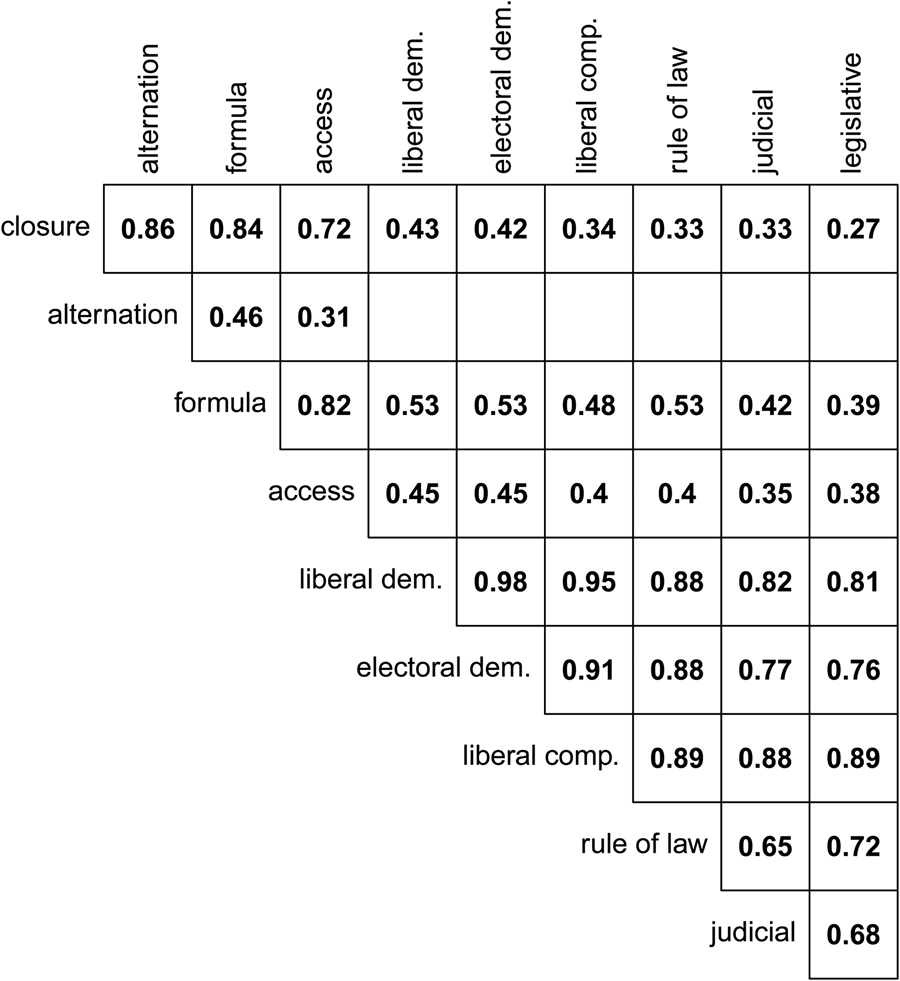

Figure 1 shows the statistically significant correlations between the components of closure and liberal democracy. Looking at bivariate relationships, liberalism and its components have a positive association with closure and its components, with the exception of alternation. At first sight, therefore, it seems that the empirical associations are in line with the optimistic expectations concerning the positive impact of party system institutionalization on the liberal dimension of democracy. Such bivariate associations, however, do not take into account other relevant characteristics of party systems and general socio-economic conditions, which are addressed by the OLS regression models in the following sections.

Figure 1. Correlations of the indices and sub-indices of closure and liberal democracy in Europe. Only coefficients significant at the 0.05 level are shown.

In order to make the different models and the effects of different variables comparable in the OLS regressions, we show standardized regression coefficients, which indicate change in standard deviations. Given the different trajectories of Eastern and Western European party systems, we tested models where the possible difference in the levels of liberal democracy between the two regions was taken into account (region dummy) and where possible differences in the effects for the closure indicators were modeled (interaction effects with region dummy), but the results did not change.

Even though the correlations between some of the predictors in the model were high (see Figure 1), multicollinearity was not a problem as all variance inflation factors were below 5 in the primary model.Footnote 6 No major influential outliers were present in the data, although whether some of the effects are significant at the 0.05 or the 0.1 level does depend on whether all cases are considered or some are left out (with such a low number of cases, this is expected). The results do not change if one excludes the cases that model diagnostics indicated as somewhat influential (Czechoslovakia, France I, Montenegro, Russia, Ukraine, Kosovo, Turkey III, Greece I, Malta) from the analysis. Finally, while analyses with a small number of cases have some obvious limitations, the advantage is that we can be relatively confident that the detected associations are valid, if they are robust to different model specifications and the range of cases included. As standard errors depend on sample size, the lower the number of cases, the stronger an association needs to be to turn up as statistically significant. See the online Appendix for more information about the models and tests that were described above.

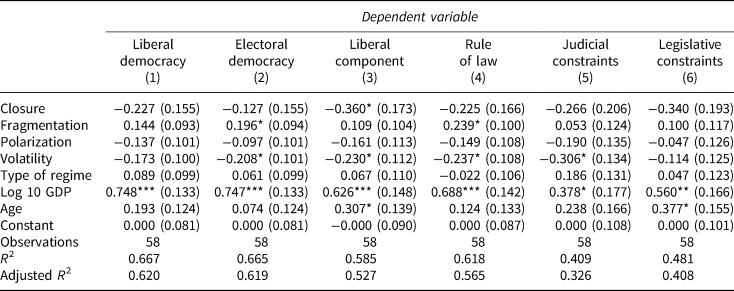

Starting from the association between the composite index of closure and the overall index of liberal democracy, the results of the analysis are shown in Table 3. It is notable here that the positive association of party system closure with liberal democracy and its components, detected at the level of bivariate relations, is no longer observable.

Table 3. Relationship between closure and measures of democracy

Standardized coefficients.

Note: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To the extent that closure is related to the various indices of democracy, the relationship is rather negative, reaching (0.05 level) statistical significance with the liberal component index (an aggregation of the rule of law, the judicial, and the legislative constraints indices).

Only some of the control variables have a clear influence on the various facets of democracy, but the impact of GDP and, to a smaller extent, the influence of the age of democracy appear to be beneficial, while the influence of electoral volatility is detrimental, in line with the expectations. Parliamentary fragmentation, somewhat surprisingly, seems to have a minor positive impact.

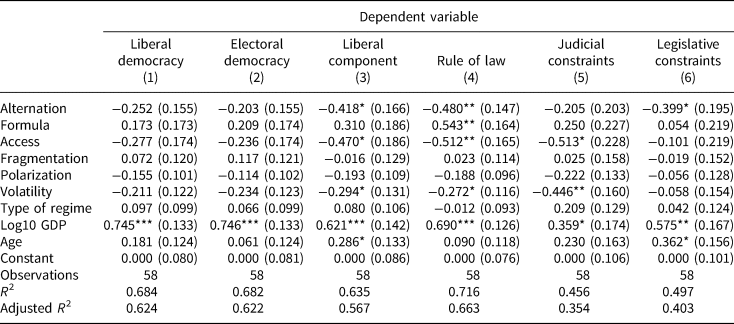

A somewhat different picture emerges if we disaggregate the closure index and test for associations between liberal democracy and its components, on one hand, and formula, access, and alternation, on the other hand (Table 4). None of the components of closure are related to the V-Dem's so-called liberal democracy index which blends indicators of electoral democracy and liberalism. This lack of association is due to a lack of covariation between closure and electoral democracy. However, if the specifically liberal dimension (the ‘liberal component’) and its sub-indices are considered, then both alternation and access have a statistically significant negative impact, undermining the rule of law, and weakening judicial constraints in case of high access (meaning low frequency of new parties included into the governments). The phenomenon that is often considered to be problematic from the point of party system institutionalization, the recombination of opposition and governmental parties into new alliances, seems to be advantageous when the rule of law is considered. The findings also suggest that the openness of governments to new parties is favorable to both rule of law and judicial constraints.

Table 4. Relationship between the components of closure and measures of democracy

Standardized coefficients.

Note: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The clearest example of the pernicious interaction between closure and the rule of law is to be found in Georgia. In this country party system institutionalization can be said to be high. According to its closure index Georgia ranks above Western Europe in this regard. The configuration of party politics is close to a perfect two-party system model, dominated by the struggle between the United National Movement and Georgian Dream. The predictable system is underpinned by the institutional framework (a disproportional mixed electoral system) and by political culture, characterized by high degree of polarization. The very same factors together with the high degree of closure lead to executive aggrandizement and a lack of respect toward rule of law. Current day Germany, however, illustrates well the environment in which the regulations of freedoms and the independent, professional operation of the judiciary is encouraged by the overlap between the consecutive cabinets.

Formula, on the other hand, has a positive association to the rule of law component of liberalism in democracy once the negative effects of alternation and access have been accounted for. The Nordic countries illustrate particularly well the positive relationship between the stabilization of coalition alternatives and the robust respect of individual freedoms, checks and balances, and equality before the law. Formula is the only component of closure that behaves as the optimistic theories of party system institutionalization would predict: the familiar, predictable patterns of coalition-building between parties who have governed together before strengthen the rule of law, and thereby liberal democracy.

As far as the control variables are concerned, minor differences can be observed between the two sets of regressions. When the composite index of closure is used, the earlier noticed small positive influence of parliamentary fragmentation is no longer discernable and the negative impact of volatility appears only for the ‘liberal component’, the rule of law, and judicial constraints indices. The second set of regressions confirms that economic development improves all aspects of democracy, while polarization has no significant impact.

In line with the expectations, the frequent return to familiar coalition formulae is conducive to more robust liberal mechanisms, while the tendency toward no change in governments entails a deterioration in the quality of the liberal dimension of democracy, particularly as far as the rule of law is concerned.

The fact that formula and access have the opposite influence is surprising since there exists a mechanical relation between them: if a new party enters a coalition, the scores of both variables decrease. Accordingly, the association between formula and access is high in the present dataset – the correlation coefficient for their association is 0.82. The two components of closure diverge when parties that have already been in government form novel coalition combinations without co-opting new partners. It seems that this segment of non-overlap, that is, the frequent innovations in the coalition-making habits of established parties, a phenomenon particularly visible in countries like Cyprus, Romania, inter-war Estonia, or post-Gürsel's coup Turkey, creates an environment in which it becomes difficult to maintain robust rule of law mechanisms as well as judicial constraints on the executive.

While the positive effect of closed formula is in line with the expectations, the negative impact of closed access runs against the expectations of the literature. The conclusion must be that in the long run those systems do better that are open to newcomers – even if keeping challenger parties out of government may be occasionally beneficial, especially if these parties are of the illiberal sort.

High values of closure on the dimension of alternation, that is, the tendency of avoiding the governmental cooperation of incumbents and previously opposition parties, typical of dominant (e.g. Georgia, Hungary) or two-party systems (e.g. contemporary Greece and Spain), was expected to have a negative effect, and the results conform to these expectations. In the case of alternation one end of the spectrum, the ‘open’ end, is defined by the configuration when half of the government stays in office, and the other half is replaced. The opposite, ‘closed’, end is defined by two types of configurations: when there is total alternation or when there is no alternation. It is justified to ask the question whether both patterns have the same impact on liberal democracy. In order to find out we ran additional models using ministerial volatility (calculated the same way as electoral volatility) and separating the two aspects of closed alternation. These additional models showed that no change in government (as opposed to partial change) had a significantly negative impact, while wholesale alternation was unrelated to the composite liberal democracy index and to its components (see Appendix). These results make good sense, as the biased use of state power is much more likely if the same parties occupy office for a long period than when governments are regularly and completely replaced.

Conclusion

The bulk of the literature suggests that highly institutionalized party systems provide a better context for high-quality democracy than the less predictable ones. Contrary to the literature, and partly contrary to our own expectations, party system institutionalization, measured in this analysis in terms of closure, was shown to have a more negative than positive impact on the liberal dimension of democracy. This negative influence was not comprehensive. The re-occurrence of the same governmental coalitions does increase, as expected, the likelihood of a robust liberal democratic regime, primarily by fostering the institutionalization of the rule of law. In this regard the general logic which associates consolidated party relations with inclusive, democratic practices applies.

But the low weight of new players has no supporting influence. It is the other way around: polities that structure governments around the same parties are, in fact, more likely to violate the rule of law and to reduce the power of judiciary over the executive. At one level, this is surprising. The countries that are most known for relying on a small circle of parties (sometimes only two) for building governments are the Anglo-Saxon countries and some of the Western European countries, the most mature democracies on earth. But if all cases are considered, these prominent examples lose their relevance, and prove to be exceptions. Typical democratic societies need to get new blood in the executive, otherwise the danger of restricting rights and liberties increases.

Finally, as far as the role of alternation is concerned, our suspicions were confirmed. In closed systems it is harder to constrain the executive. If the new governments contain members of previous governments, but also some parties who have fought the election from the opposition, then a more self-limiting executive culture develops.

Elsewhere (Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2017; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021) it has been shown both that the role of closure is essential for sustaining democratic regimes and that in wealthy European societies the quality of democracy is positively influenced by high degree of party system institutionalization. However, some negative influences have also been documented in poorer European societies (Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021: 255). The results of this paper show that the relationship is even more complex as different components of closure have diverging impacts.

Given these diverging mechanisms, it is no wonder that the composite closure scale does not show a significant impact on the liberal dimension of democracy. But because two of its three components have a negative impact, closure itself can be considered to undermine rather than strengthen liberal democracy.

What should then be the advice for those who care about the liberal dimension of democracy? Should they undermine the institutionalization of party systems? This would certainly go too far. It is in fact good to have parties who show loyalty to each other and who continue to cooperate in government with their former allies, and high electoral volatility must remain a cause for concern. Under the conditions of large electoral instability and lack of continuity in governmental alliances parties are incentivized to exploit to the maximum the temporarily held dominant position. But the recurrent incorporation of new partners into the party alliances and into the government, while it may decrease the overall institutionalization of the party system, is to be encouraged, if the goal is to maximize the liberal aspects of democracy.

The reassessment of the party system–democracy linkage has been made urgent by the recent proliferation of hybrid regimes and of various forms of defective democracy. By now virtually all drastic drops in the quality of democracy are due to the actions of democratically elected incumbents (Svolik, Reference Svolik2019). In illiberal electoral democratic regimes parties are, at least formally, important players, while power is concentrated. The electoral thresholds in most such countries are relatively high, and the campaign rules are restrictive, with the goal of keeping troublemakers out. The result is the concentration of power in the hands of a few players.

Our study suggests that the ossification of party systems is as large, or possibly even larger, danger for liberal democracy than the chaotic functioning of the parties. In order to keep party systems compatible with individual rights and limited government, one needs to accept and even encourage the access of new parties to government. Even more importantly, the cooperation of previous opponents in the executive should be welcome. While such recombination of parties may create more complexity, and in this regard may make the choice of citizens more difficult, it supports the culture in which powers are divided and counter-majoritarian institutions flourish.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2022.22

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp