No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

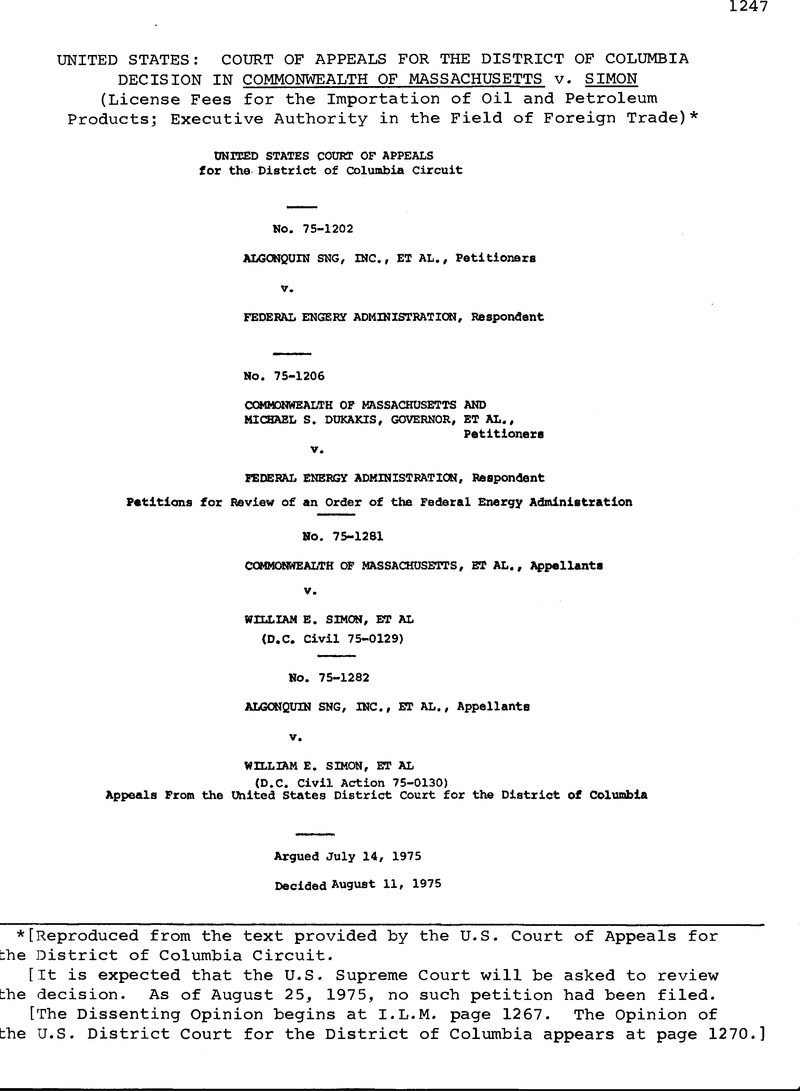

United States: Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Decision in Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Simon (License Fees for the Importation of Oil and Petroleum Products; Executive Authority in the Field of Foreign Trade)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1975

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for bhe District of Columbia Circuit.

[It is expected that the U.S. Supreme Court will be asked to review bhe decision. As of August 25, 1975, no such petition had been filed.

[The Dissenting Opinion begins at I.L.M. page 1267. The Opinion of bhe U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia appears at page 1270.]

References

page 1250 note * [The Trade Act of 1974 appears at 14 I.L.M. 181 (1974).]

page 1253 note * [The Trade Expansion Act of 1962 appears at 1 I.L.M. 340 (1962).]

page 1260 note * [The Customs Court decision appears at 13 I.L.M. 1126 (1974).]

page 1265 note 1/ The term “petroleum” as used herein refers to both crude oil, unfinished oils (which encompasses a variety of refined petroleum products) and finished products.

page 1265 note 2/ See United States Tariff Commission, World Oil Developments and U.S. OilTrnport Policies, T.C. Publication 632 at 46-48 (19731 rhereinafter Tariff Commission Report). Many of these modifications, especially in the period 1970-73, were necessary to meet the gap between domestic supply and demand. As such, MOIP failed to accomplish its stated objective of reducing dependence on foreign oil. See generally id. at 42-70.

page 1265 note 3/ The fees were to increase during that period from 10.5 to 21 cents/bbl for crude oil, from 52 to 63 cents/bbl for motor gasoline and from 15 to 63 cents/bbl for finished products and unfinished oils. Proc. 4210 §3(a).

page 1265 note 4/ The investigation may be commenced upon “request of the head of any department or agency, upon application of an interested party,” or upon the Secretary's own motion. The Secretary must submit his recommendation for action or inaction within one year of the receipt of a request for or the start of an investigation.

page 1266 note 5/ See 40 Fed. Reg. 4412-4465 (1975). Substantive responses were received from all departments except Labor who wrote that it could not conduct an appropriate investigation within the ten day time limit imposed by Secretary Simon.

page 1266 note 6/ Proc. 4341 did not affect the fee-free quotas under the Nixon-imposed fees, nor the schedule for their elimination. President Ford also reinstated the tariffs on petroleum products removed in 1973, but provided that they could be offset against the supplemental fees.

On February 19, 1975, Congress passed a bill imposing a 90-day moratorum upon the implementation of Proc. 4341. H.R. 1767, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975). On March 4th, President Ford vetoed the bill, but suspended the imposition of the supplemental fees for two months. See 121 Cong. Rec. H. 1403; Proc. 4355, 40 Fed. Reg. 10437 (1975). On April 30th, he continued the suspension for an additional thirty days. Proc. 4370, 40 Fed. Reg. 19421 (1975). Finally, on June 1, 1975, President Ford imposed the second dollar of the supplemental fee. Proc. 4377, 40 Fed. Reg. 23429 (1975).

page 1266 note 7/ Commonwealth of Massachusetts and Governor Michael S. Dukakis; State of Connecticut and Governor Ella Grasso; State of Maine and Governor James B. Longley; State of New Jersey and Governor Brendan T. Byrne; State of New York and Governor Hugh Carey; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Governor Milton J. Shapp; State of Rhode Island and Governor Philip W. Noel; and State of Vermont and Governor Thomas P. Salmon. The State of Minnesota subsequently intervened as a plaintiff.

page 1266 note 8/ Algonquin SNG, Inc., New England Power Co., New Bedford gas and Edison Light Co., Cambridge Electric Light Co., Canal Electric Co., Montaup Electric Co., the Connecticut Light and Power Co., the Hartford Electric Light Co., Western Massachusetts Electric Light Co., and Holyoke Water Co.

page 1266 note 9/ Representative Robert P. Drinan, SJ.

page 1266 note 10/ In response a motion by appellants, consented to by the government, the district court pursuant to Fed. R.Civ. P. 65 ordered that its conclusions, with respect to preliminary relief, constitute the court's final judgment.

page 1266 note 11/ The one additional issue raised in the appeal of the Implementing regulations is appellants' contention that the PEA violated the procedural provisions of the Federal Energy Administration Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 761 et seg. In light of our conclusion that the President does not possess substantive power to impose the challenged fees, we do not reach this question.

page 1266 note 12/ Congress also mandated in this connection that the Tariff Commission was to have an advisory role in the process and that President designate an agency to conduct public hearings. 19 U.S.C. §§ 1841, 1843.

page 1266 note 13/ Proc. 4341 was expected to generate $4.8 billion in annual revenues. In 1974 total revenues from all tariffs were $4.3 billion. See White House Fact Sheet at 13, J.A. 170. J.S. Customs Service, Activity Report, Fiscal Year 1974.

page 1266 note 14/ Senator Holland opposed the bill. While statements of opponents normally are no authorative guide to construing the statute, see Bauers v. Heisel, 361 F.2d 581 (3rd Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 386 U.S. 1021 (1967), they may sometimes be useful, especially where proponents make no response.Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963). In this case, we find Senator Holland's statement relevant in light of the fact that his view eventually prevailed.

page 1267 note 15/ The Court also noted that an assessment is made heavy Tr the activity in question was to be discouraged and that the levy is “slight if a bounty is to be bestowed” but concluded that “[s]uch assessments are in the nature of ‘taxes’ which under our constitutional regime are traditionally levied by Congress.” 415 U.S. at 341. Of course, assessing fees to discourage activity is the core of the challenged program.

page 1267 note 16/ The President has created a new mechanism for import adjustment called a license fee. The analysis, however, suggests that what Proclamation 4210 does is substitute a duty system for the quota mechanism of the Mandatory Oil Import Program, for the license fee has the incidences of a duty. The name is new and the administration has been shifted from the Department of the Treasury, (U.S.) Customs Service to the Department of the Interior. Nonetheless, the new program is substantively a duty system[.]

Tariff Commission Report at 97.

page 1267 note 17/ While there may be a useful concept of a fee based on “benefit” the term would be grossly distorted if stretched to this case on the ground that if there were no “benefit” the importer would not pay the charge and consummate the import, for that kind of stretch would make it applicable to all tariffs and duties.

page 1267 note 18/ Similarly, Section 1862(b) would not allow a President to suspend duly enacted tariffs such as President Nixon did in Proclamation 4210. Of course, .President Ford reimposed the tariffs in Proclamation 4341, and no relief is now appropriate.

page 1270 note 1/ The fee Is supplemental because it is Imposed in addition to certain license fees provided by Presidential Proclamation 4210 issued by President Nixon on April 18, 1973.