No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

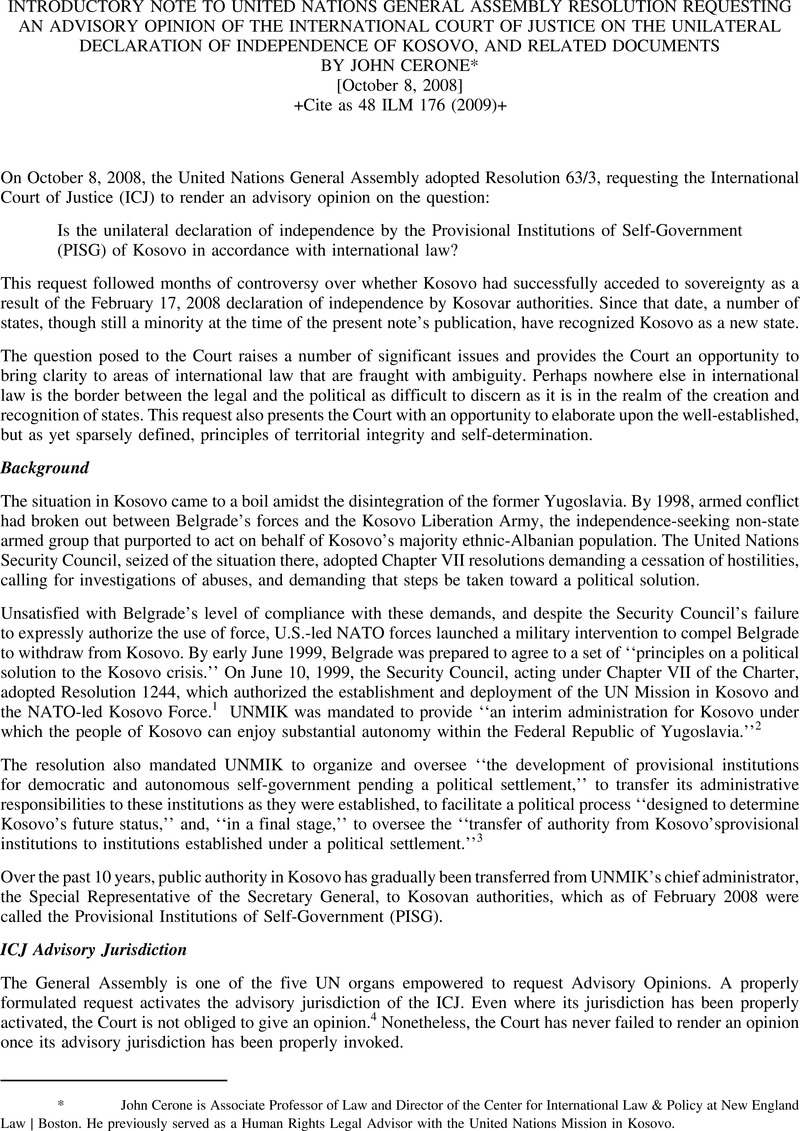

United Nations General Assembly Resolution Requesting an Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice on the Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Kosovo, and Related Documents

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- International Legal Material

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2009

References

End notes

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the United Nations website: (visited February 10, 2009)< http://issuu.com/i.l.m./docs/un_ga_serbia_kosovo_resolution>

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the United Nations website: (visited February 10, 2009)< http://issuu.com/i.l.m./docs/un_ga_serbia_kosovo_resolution>

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the United Nations website: (visited February 10, 2009)< http://issuu.com/i.l.m./docs/un_ga_serbia_kosovo_resolution>

1 S.C. Res. 1244, U.N. Doc. S/RES/1244 (June 10, 1999) [hereinafter Resolution 1244].

2 Id. ¶ 10.

3 Id. ¶ 11.

4 Article 65(1) of the Court’s Statute provides that the “Court may give an advisory opinion on any legal question at the request of whatever body may be authorized by or in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations to make such a request” (emphasis added).

5 Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, 2003 I.C.J. 428 (Dec. 19).

6 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, Dec. 26, 1933, 49 Stat. 3097, 165 U.N.T.S. 21.

7 In addition, commentators have speculated that there is an emerging trend toward incorporation of a human rights dimension into the question of the creation and recognition of states. In particular, some have asserted the existence of a soft law norm requiring non-recognition in the face of massive human rights violations.

8 This may be a basis of distinction with respect to South Ossetia, which is otherwise parallel in many respects, and also with respect to Northern Cyprus, though in that situation the Security Council has affirmatively rejected the legality of the situation. As for South Ossetia, while it may be argued that Georgia agreed to the presence of the Russian peacekeepers (though the validity of that agreement is open to question given the circumstances surrounding its conclusion), the conduct of the latter, from the beginning, clearly exceeded the scope of Georgian consent. Another basis of distinction may be found with respect to the degree of independence enjoyed by the authorities. Many of the South Ossetian ‘authorities’ are Russian public officials (i.e. not merely installed by Moscow, but were already organs of the Russian Federation and continue to serve in that capacity).

9 Perhaps if Kosovo’s secession was the direct result of that violation, it could be argued that there is an obligation to refrain from recognizing the new state. A counter-argument would be that the Security Council’s authorization of KFOR’s presence was a supervening legal event. While this supervening legal event could not retroactively authorize the NATO bombing, and thus could not afford a valid basis for territorial claims made by NATO countries, it could break the causal connection between that bombing and Kosovo’s attempted secession.

10 Resolution 1244, supra note 1, pmbl.

11 Id. ¶ 11.

12 Id. ¶ 10.

13 Id.

14 This is, arguably, reinforced by the way in which UNMIK is conceived throughout the resolution. The resolution envisions UNMIK as a neutral facilitator, while at the same time implying movement (“transitional”) and direction (“autonomy”; “democratic self-governing institutions”). Thus, the language of enabling the enjoyment of substantial autonomy may be seen as stipulating UNMIK’s goal as an interim presence.

15 In this capacity, however, it may be regarded as being competent to act only on behalf of the territory and population group that it actually controls (i.e. south of the Ibar).