No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

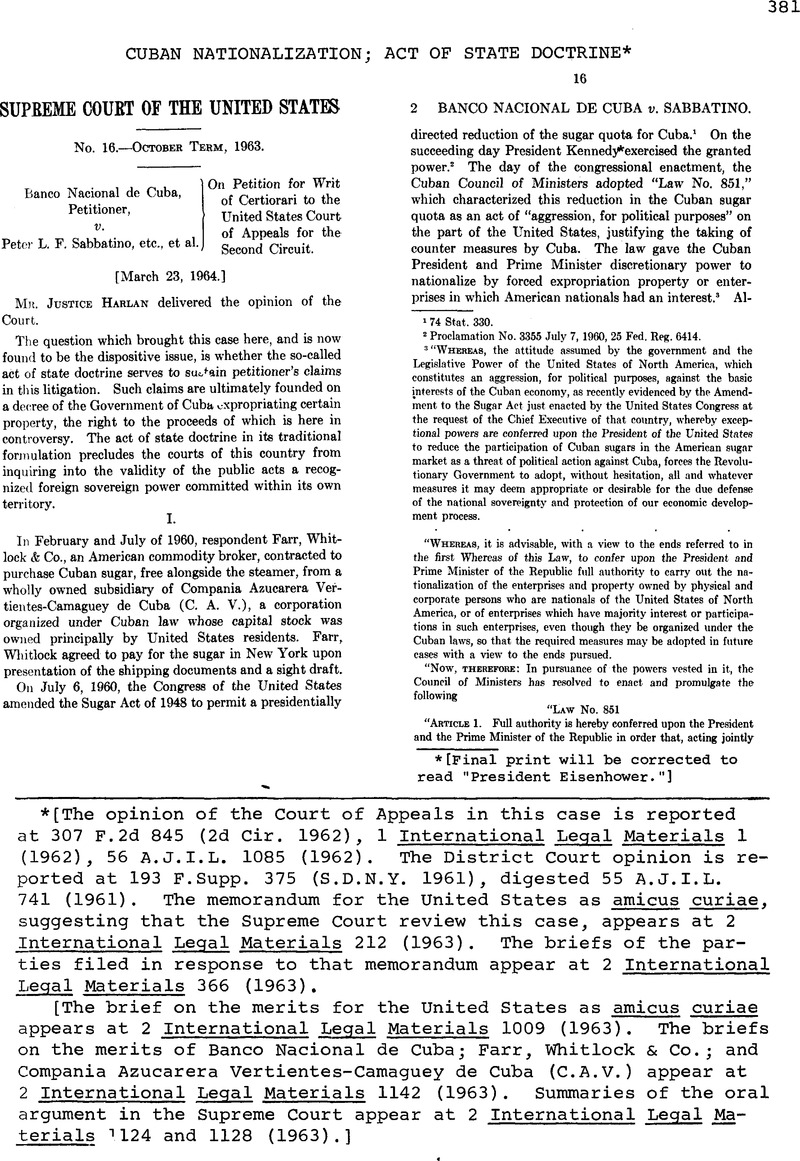

Cuban Nationalization; Act of State Doctrine*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Supplement

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1964

Footnotes

[The opinion of the Court of Appeals in this case is reported at 307 F.2d 845 (2d Cir. 1962), 1 International Legal Materials 1 (1962), 56 A.J.I.L. 1085 (1962). The District Court opinion is reported at 193 F.Supp. 375 (S.D.N.Y. 1961), digested 55 A.J.I.L. 741 (1961). The memorandum for the United States as amicus curiae, suggesting that the Supreme Court review this case, appears at 2 International Legal Materials 212 (1963) . The briefs of the parties filed in response to that memorandum appear at 2 International Legal Materials 366 (1963). [The brief on the merits for the United States as amicus curiae appears at 2 International Legal Materials 1009 (1963). The briefs on the merits of Banco Nacional de Cuba; Farr, Whitlock & Co.; and Compania Azucarera Vertientes-Camaguey de Cuba (C.A.V.) appear at 2 International Legal Materials 1142 (1963). Summaries of the oral argument in the Supreme Court appear at 2 International Legal Materials 1124 and 1128 (1963).]

References

8 C. A. V. also agreed to pay Farr, Whitlock 10% of the $175,000 if C. A. V. ever obtained that sum. 307 F. 2d, at 851.

9 Because of C. A. V.'s amicus position in this Court, and because its arguments have been presented separately from those of Farr, Whitlock, even though each has adopted the other's contentions, this opinion refers to “respondents” although Farr, Whitlock is the only formal party-respondent.

10 In P. & E. Shipping Corp. v. Banco Para el Comercio Exterior de Cuba, 307 F. 2d 415 (C. A. 1st Cir.), the court sua sponte questioned the right of Cuba to sue. It concluded that the matter was one for the Executive Branch to decide and remanded the case to the District Court to elicit the views of the State Department. The trial court in Dade Drydock Corp. v. The M/T Mar Caribe, 199' F. Supp. 871 (S. D. Tex.), apparently equated the severance of diplomatic relations with the withdrawal of recognition and suspended the action “until the Government of the Republic of Cuba is again recognized by the United States of America,” id., at 874. In two other cases, however, Pons v. Republic of Cuba 294 F. 2d 925 (C. A. D. C. Cir.); Republic of Cuba v. Mayan Lines, S. A., 145 So. 2d 679 (Ct. App., 4th Cir., La.), courts have upheld the right of Cuba to sue despite the severance of diplomatic relations.

11 The District Court in The “Gul Djemal,” 296 F. 563, 296 F. 567, did refuse to permit the invocation of sovereign immunity by the Turkish Government, with whom the United States had broken diplomatic relations, on the theory that under such circumstances comity did not require the granting of immunity. The case was affirmed, 264 U. S. 90, but on another ground.

12 The doctrine that nonrecognition precludes suit by the foreign government in every circumstance has been the subject of discussion and criticism. See, e. g., Hervey, The Legal Effects of Recognition in International Law (1928) 112-119; Jaffe, Judicial Aspects of Foreign Relations (1933) 148-156; Borchard, The Unrecognized Government in American Courts, 26 Am. J. Int'l L. 261 (1932); Dickinson, The Unrecognized Government or State in English and American Law, 22 Mich. L. Rev. 118 (1923); Fraenkel, The Juristic Status of Foreign States, Their Property and Their Acts, 25 Col. L. Rev. 544, 547-552 (1925); Lubman, The Unrecognized Government in American Courts: Upright v. Mercury Business Machines, 62 Col. L. Rev. 275 (1962). In this litigation we need intimate no view on the possibility of access by an unrecognized government to United States courts, except to point out that even the most inhospitable attitude on the matter does not dictate denial of standing here.

13 Respondents suggest that suit may be brought, if at all, only by an authorized agent of the Cuban Government. Decisions establishing that privilege based on sovereign prerogatives may be evoked only by such agents, e. g., The Anne, 3 Wheat. 435; Ex parte Muir, 254 U. S. 522, 532-533; The Sao Vicente, 260 U. S. 151; The “Gut Djemal,” 264 U. S. 90, are not apposite to cases in which a state merely sues in our Courts without claiming any right uniquely appertaining to sovereigns.

14 If Cuba had jurisdiction to expropriate the contractual right, it would have been unnecessary for it to compel the signing of a new contract. If Cuba did not have jurisdiction, any action which it took in regard to Farr, Whitlock or the sugar would have been ineffective to transfer C. A. V.'s claim.

15 As appears from the cases cited, a penal law for the purposes of this doctrine is one which seeks to redress a public rather than a private wrong.

16 The doctrine may have a broader reach in Great Britain, see Don Alonso v. Cornero, Hob. 212a, Hobart's King's Bench Reps. 372; Banco de Vizcaya v. Don Alfonso de Borbon Y Austria [1935] 1 K. B. 140; Attorney-General for Canada v. William Schulze & Co. [19011 9 Scots L. T. Reps. 4 (Outer House); Dicey's Conflict of Laws 162 (Morris ed. 1958); Mann, Prerogative Rights of Foreign States and The Conflict of Laws, 40 Grotius Society 25 (1955); but see Lepage v. San Paulo Coffee Estates Co. [1917] W. N. 216 (High Ct. of Justice, Ch. Div.); Lorentzen v. Lydden & Co. [1942] 2 K. B. 202; F. & K. Jabour v. Custodian of Israeli Absentee Property [1954] 1 W. L. R. 139 (Q. B.), than in the United States, cf. United States v. Belmont, 85 F. 2d 542, rev'd, 301 TJ. S. 324 (possibility of broad rule against enforceability of public acts not discussed in either court), United States v. Pink, 284 N. Y. 555, rev'd, 315 U. S. 203 (same); Anderson v. N. V. Transandine Handelmaatschappij, 289 N. Y. 9, 43 N. E. 2d 502; but see Leflar, Extrastate Enforcement of Penal and Governmental Claims, 46 H. L. R. 193, 194 (1932).

17 The courts below properly declined to determine if issuance of the expropriation decree complied with the formal requisites of Cuban law. In dictum in Hudson v. Guestier, 4 Cranch 293, 294, Chief Justice Marshall declared that one nation must recognize the act of the sovereign power of another, so long as it has jurisdiction under international law, even if it is improper according to the internal law of the latter state. This principle has been followed in a number of cases. See, e. g., Banco de Espana v. Federal Reserve Bank, 114 F. 2d 438, 443, 444 (C. A. 2d Cir.); Bernstein v. Van Heyghen Freres Societe Anonyme, 163 F. 2d 246, 249 (C. A. 2d Cir.); Eastern States Petroleum Co. v. Asiatic Petroleum Corp., 28 F. Supp. 279 (D. C. S. D. N. Y.). But see Canada Southern R. Co. v. Gebhard, 109 U. S. 527; cf. Fremont v. United States, 17 How. 542 (United States successor sovereign over land); Sabariego v. Maverick, 124 U. S. 261 (same); Shapleigh v. Mier, 299 U. S. 468 (same). An inquiry by United States courts into the validity of an act of an official of a foreign state under the law of that state would not only be exceedingly difficult but, if wrongly made, would be likely to be highly offensive to the state in question. Of course, such review can take place between States in our federal system, but in that instance there is similarity of legal structure and an impartial arbiter, this Court, applying the full faith and credit provision of the Federal Constitution.

Another ground supports the resolution of this problem in the courts below. Were any test to be applied it would have to be what effect the decree would have if challenged in Cuba. If no institution of legal authority would refuse to effectuate the decree, its “formal” status—here its argued invalidity if not properly published in the Official Gazette in Cuba—is irrelevant. It has not been seriously contended that the judicial institutions of Cuba would declare the decree invalid.

“The letter stated:

“1. This government has consistently opposed the forcible acts of dispossession of a discriminatory and confiscatory nature practiced by the Germans on the countries or peoples subject to their controls.

“3. The policy of the Executive, with respect to claims asserted in the United States for the restitution of identifiable property (or compensation in lieu thereof) lost through force, coercion, or duress as a result of Nazi persecution in Germany, is to relieve American courts from any restraint upon the exercise of their jurisdiction to pass on the validity of the acts of Nazi officials.” State Department Press Release 296, April 27, 1949, 20 State Dept. Bull. 592.

19 Abram Chayes, the Legal Adviser to the State Department, wrote on October 18, 1961, in answer to an inquiry regarding the position of the Department by Mr. John Laylin, attorney for amid:

“The Department of State has not, in the Bahia de Nipe case or elsewhere, done anything inconsistent with the position taken on the Cuban nationalization by Secretary Herter. Whether or not these nationalizations will in the future be given effect in the United States is, of course, for the courts to determine. Since the Sabbatino case and other similar cases are at present before the courts, any comments on this question by the Department of State would be out of place at this time. As you yourself point out, statements by the executive branch are highly susceptible of misconstruction.“

A letter dated November 14, 1961, from George Ball, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs, responded to a similar inquiry by the same attorney:

“I have carefully considered your letter and have discussed it with the Legal Adviser. Our conclusion, in which the Secretary concurs, is that the Department should not comment on matters pending before the courts.“

20 Although the complaint in this case alleged both diversity and federal question jurisdiction, the Court of Appeals reached jurisdiction only on the former ground, 307 F. 2d, at 852. We need not decide, for reasons appearing hereafter, whether federal question jurisdiction also existed.

21 In English jurisprudence, in the classic case of Luther v. James Sagor A Co.. [1921] 3 K. B. 532, the act of state doctrine is articulated in terms not unlike those of the United States cases. See Princess Paley Olga v. Wekz. [19291 1 K. B. 718. But see Anglo- Iranian Oil Co. v. Jafirate (The Rose Mary), [1953] 1 Weekly L. R. 246, [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 316 (Supreme Court of Aden) (exception to doctrine if foreign act violates international law). Civil law countries, however, which apply the rule make exceptions for acts contrary to their sense of public order. See, e. g., Ropit case, Cour de Cassation (France), [1929] Recueil General Des Lois et Des Arrets (Sirey) Part I, 217; 55 Journal Du Droit International (Clunet) 674 (1928), [1927-1928] Ann. Dig., No. 43; Graue, Germany: Recognition of Foreign Expropriations, 3 Am. J. Comp. L. 93 (1954); Domke, Indonesian Nationalization Measures Before Foreign Courts, 54 Am. J. Int'l L. 305 (1960) (discussion of and excerpts from opinions of the District Court in Bremen and the Hanseatic Court of Appeals in N. V. Verenigde Deli-Maatschapijen v. Deutsch-Indonesische Tabak-Handelsgesellschaft m. b. H.. and of the Amsterdam District Court and Appellate Court in Senembah Maatschappij N. V. v. Republiek Indonesie Bank Indonesia); Massouridis, The Effects of Confiscation, Expropriation, and Requisition by a Foreign Authority, 3 Revue Hellenique De Droit International 62, 68 (1950) (recounting a decision of the court of the first instance of Piraeus); Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. S. U. P. O. R. Co., Civil Tribunal of Venice [1955] Int'l L. Rep. 19, 78 II Foro Italiano Part I, 719: 40 Blatter fur Zurcherisehe Rechtsprechung No. 65, 172-173 (Switzerland). See also Anglo- Iranian Oil Co. v. Idemitsu Kosan Kabushiki Kaisha, [1953] Int'l L.. Rep. 312 (High Court of Tokyo).

22 See, e. g., Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Committee on International Law, A Reconsideration of the Act of State Doctrine in United States Courts (1959); Domke, supra, note 21; Mann, International Delinquencies Before Municipal Courts, 70 L. Q. Rev. 181 (1954); Zander, The Act of State Doctrine, 53 Am. J. Int'l L. 826 (1959). But see, e. g., Falk, Toward a Theory of the Participation of Domestic Courts in the International Legal Order: A Critique of Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 16 Rutgers L. Rev. 1 (1961); Reeves, Act of State Doctrine and the Rule of Law— A Reply, 54 Am. J. Int'l L. Rev. 141 (1960).

23 At least this is true when the Court limits the scope of judicial inquiry. We need not now consider whether a state court might, in certain circumstances, adhere to a more restrictive view concerning the scope of examination of foreign acts than that required by this Court.

24 The Doctrine of Erie Railroad v. Tompkins Applied to International Law, 33 Am. J. Int'l L. 740 (1939).

25 Various constitutional and statutory provisions indirectly support this determination, see XJ. S. Const., Art. I, §8, els. 3, 10; Art. II, §§2,3; Art. Ill, §2; 28 U. S. C. §§ 1251 (a)(2), (b)(1), (b)(3), 1332 (a)(2), 1333, 1350-1351, by reflecting a concern for uniformity in this country's dealings with foreign nations and indicating a desire to give matters of international significance to the jurisdiction of federal institutions. See Comment, The Act of State Doctrine— Its Relation to Private and Public International Law, 62 Col. L. Rev., 1278,1297, n. 123; cf. United States v. Belmont, suvra; United States v. Pink, supra.

26 Compare, e. g” Friedman, Expropriation in International Lav 206-211 (1953); Dawson and Weston, Prompt, Adequate and Effective: A Universal Standard of Compensation? 30 Fordham L. Rev 727 (1962), with Note from Secretary of State Hull to Mexican Ambassador, August 22, 1938, V Foreign Relations of the United“ States 685 (1938); Doman, Postwar Nationalization of Foreign Property in Europe, 48 Col. L. Rev. 1125, 1127 (1948). We do not, of course, mean to say that there is no international standard in this area; we conclude only that the matter is not meet for adjudication by domestic tribunals.

27 See Oscar Chinn Case, P. C. I. J., ser. A/B, No. 63, at 87 (1934) ; Chorzow Factory Case, P. C. I. J., ser. A., No. 17, at 46, 47 (1928).

28 See, e. g., Norwegian Shipowners’ Case (Norway/United States) (Perm. Ct. Arb.) (1922), 1 U. N. Rep. Int'l Arb. Awards 307, 334„ 339 (1948), Hague Court Reports, 2d Series, 39, 69, 74 (1932); Marguerite de Joly de Sabla, American and Panamanian General Claims Arbitration 379, 447, 6 U. N. Rep. Int'l Arb. Awards 358, 366 (1955).

29 See, e. g., Dispatch from Lord Palmerston to British Envoy at Athens, Aug. 7, 1846, 39 British and Foreign State Papers 1849-1850, 431-432. Note from Secretary of State Hull to Mexican Ambassador, July 21, 1938, V Foreign Relations of the United States 674 (1938); Note to the Cuban Government, July 16, 1960, 43 Dept. State Bull. 171 (1960).

30 See, e. g., McNair, The Seizure of Property and Enterprises in Indonesia, 6 Netherlands Int'l L. Rev. 218, 243-253 (1959); Restatement, Foreign Relations Law of the United States (Proposed Official Draft 1962), §§ 190-195.

31 See Doman, supra, note 26, at 1143-1158; Fleming, States, Contracts and Progress, 62-63 (1960); Bystricky, Notes on Certain International Legal Problems Relating to Socialist Nationalization, in International Assn. of Democratic Lawyers, Proceedings of the Commission on Private International Law, Sixth Congress (1956), 15.

32 See Anand, Role of the “New” Asian-African Countries in the Present International Legal Order, 56 Am. J. Int'l L. 383 (1962); Roy, Is the Law of Responsibility of States for Injuries to Aliens a Part of Universal International Law? 55 Am. J. Int'l L. 863 (1961).

33 See 1957 Yb. U. N. Int'l L. Comm'n (Vol. 1) 155, 158 (statements of Mr. Padilla Nervo (Mexico) and Mr. Pal (India)).

34 There are, of course, areas of international law in which consensus as to standards is greater and which do not represent a battleground for conflicting ideologies. This decision in no way intimates that the courts of this country are broadly foreclosed from considering questions of international law.

35 See Restatement, Foreign Relations Law of the United States, Reporters’ Notes (Proposed Official Draft 1962), §43, note 3.

36 It is, of course, true that such determinations might influence others not to bring expropriated property into the country, see pp. 33-34, infra, so their indirect impact might extend beyond the actual invalidations of title.

37 Of course, to assist respondents in this suit such a determination would have to include a decision that for the purpose of judging this expropriation under international law C. A. V. is not to be regarded as Cuban and an acceptance of the principle that international law provides other remedies for breaches of international standards of expropriation than suits for damages before international tribunals. See 307 F. 2d, at 861, 868 for discussion of these questions by the Court of Appeals.

38 This possibility is consistent with the view that the deterrent effect of court invalidations would not ordinarily be great. If the expropriating country could find other buyers for its products at roughly the same price, the deterrent effect might be minimal although patterns of trade would be significantly changed.

39 Were respondents’ position adopted, the courts might be engaged in the difficult tasks of ascertaining the origin of fungible goods, of considering the effect of improvements made in a third country on expropriated raw materials, and of determining the title to commodities subsequently grown on expropriated land or produced with expropriated machinery.

By discouraging import to this country by traders certain or apprehensive of nonrecognition of ownership, judicial findings of invalidity of title might limit competition among sellers; did the excluded goods constitute a significant portion of the market, prices for United States purchasers might rise with a consequent economic burden on United States consumers. Balancing the undesirability of such a result against the likelihood of furthering other national concerns is plainly a function best left in the hands of the political branches.

1 The courts of the following countries, among others, and their territories have examined a fully “executed” foreign act of state expropriating property:

England: Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Jafirate (The Rose Mary), [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 316 (Aden. Sup. Ct.); N. V. De Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij v. The War Damage Coram., [1956] Int'l L. Rep. 810 (Singapore Ct. App.).

Netherlands: Senembah Maatschappij, N. V. v. Rupubliek Indonesie Bank Indonesia, 73 Nederlandse Jurisprudence 218 (Amsterdam Ct. App.), excerpts reprinted in Domke, Indonesian Nationalization Measures Before Foreign Courts, 54 Am. J. Int'l L. 305, 307-315 (1960).

Germany: N. V. Verenigde Deli-Maatschapijen v. Deutsch-Indonisische Tabak-Handelsgesellsehaft m. b. H. (Bremen Ct. App.), excerpts reprinted in Domke, supra, at 313-314 (1960); Confiscation of Property of Sedenten Germens Case, [1948] Ann. Dig. 24, 25 (No. 12) (Amstgericht of Dingolfing).

Japan: Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Idemitsu Kosan Kabushiki Kaisha, [1053] Int'l L. Rep. 305 (Tokyo Dist. Ct,), aff'd, [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 312 (Tokyo High Ct,).

Italy: Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. S. U. P. O. R. Co. [1955] Int'l L. Rep. 19 (Ct, of Venice); Anglo Iranian Oil Co. v. S. V. P. O. R., [1055] Int'l L. Rep. 23 (Civil Ct. of Rome).

France: Volatron v. Moulin. [1938-1940] Ann. Dig. 24 (Ct. of App. of Aix); Societe Potasas Iberkas v. Nathan Bloch, [1938-1940] Ann. Dig. 150 (Ct. of Cassation).

The Court does not refer to any country which has applied the act of state doctrine in a case where a substantial international law issue is sought to be raised by an alien whose property has been expropriated. This country and this Court stand alone among the civilized nations of the world in ruling that such an issue is not cognizable in a court of law.

The Court notes that both the courts of New .Jork and Great Britain have articulated the act of state doctrine in broad language similar to that used by this Court in Underbill, supra, and from this it infers that these courts recognize no international law exception to the act of state doctrine. The cases relied on by the Court involved no international law issue. For in these cases the party objecting to the validity of the foreign act was a citizen of the foreign state. It is significant that courts of both New York and Great Britain, in apparently the first cases in which an international law issue was squarely posed, ruled that the act of state doctrine was no bar to examination of the validity of the foreign act. Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Jaflrate (The Rose Mary), [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 316 (Aden Sup. Ct.): “[T]he Iranian laws of 1951 were invalid by international law, for, by them, the property of the company was expropriated without any compensation.” Sulyok v. Penzintezeti Kozpont Budapest, 279 App. Div. 528, aff'd, 304 N. Y. 704 (foreign expropriation of intangible property denied effect as contrary to New York public policy).

2 In one of the earliest decisions of this Court even arguably invoking the act of state doctrine, Hudson v. Guestier, 4 Cranch 293, Chief Justice Marshall held that the validity of a seizure by a foreign power of a vessel within the jurisdiction of the sentencing court could not be reviewed “unless the court passing sentence loses its jurisdiction by some circumstance which the law of nations can recognize.“ Underhill v. Hernandez. 168 U. S. 250, where the Court stated the act of state doctrine in its oft quoted form, was a suit in tort by an American citizen against an officer of the Venezuelan Government for an unlawful detention and compelled operation of the plaintiff'swater facilities during the course of a revolution in that country. Well-established principles of immunity precluded the plaintiff's suit, and this was one of the grounds for dismissal. However, as noted above, the Court did invoke the act of state doctrine in dismissing the suit and arguably the forced detention of a foreign citizen posed a claim cognizable under international law. But the Court did not ignore this possibility of a violation of international law; rather in distinguishing cases involving arrests by military authorities in the absence of war and those concerning the right of revolutionary bodies to interfere with commerce, the Court passed on the merits of plaintiff's claim under international law and deemed the claim without merit under then existing doctrines. “Acts of legitimate warfare cannot be made the basis of individual liability.” (Emphasis added.) 168 U. S., at 253. Indeed the Court cited Dow v. Johnson, 100 TJ. S. 158, a suit arising from seizures by American officers in the South during the Civil War, in which it was held without any reliance on the act of state doctrine that the law of nations precluded making acts of legitimate warfare a basis for liability after the cessation of hostilities, and Ford v. Surget, 97 U. S. 594, which held an officer of the confederacy immune from damages for the destruction of property during the war. American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co.. 213 U. S. 347, a case often invoked for the blanket prohibition of the act of state doctrine, held only that the antitrust laws did not extend to acts committed by a private individual in a foreign country with the assistance of a foreign government. Most of the language in that case is in response to the issue of how far legislative jurisdiction should be presumed to extend in the absence of an express declaration. The Court held that the ordinary understandings of sovereignty warranted the proposition that conduct of an American citizen should ordinarily be adjudged under the law where the acts occurred. Rather than ignoring international law, the law of nations was relied on for this rule of statutory construction.

More directly on point are the Mexican seizures passed upon in Oetjen, 246 U. S. 297, and Ricaud, 246 U. S. 304. In Oetjen the plaintiff claimedjitle from a Mexican owner who was divested of his property during the Mexican revolution. The terms of the expropriation are not clear, but it appears that a promise of compensation was made by the revolutionary government and that the property was to be used for the war effort. The only international law issue arguably present in the case was by virtue of a treaty of the Hague Convention, to which both Mexico and the United States were signatories, governing customs of war on land; although the Court did not rest the decision on the treaty, it took care to point out that this seizure was probably lawful under the treaty as a compelled contribution in time of war for the needs of the occupying army. Moreover, the Court stressed the fact that the title challenged was derived from a Mexican law governing the relations between the Mexican Government and Mexican citizens. Aside from the citizenship of the plaintiff's predecessor in title, the property seized was to satisfy an assessment of the revolutionary government which the Mexican owner had failed to pay. It is doubtful that this measure, even asapplied to non-Mexicans, would constitute a violation of international law. Dow v. Johnson, supra. In Ricaud the titleholder was an American and the Court deemed this difference irrelevant “for the reasons given in Oetjen.” In Ricaud there was a promise to pay for the property seized during the revolution upon the cessation of hostilities and the seizure was to meet exigencies created by the revolution, which was permissible under the provisions of the Hague Convention considered in Oetjen. This declaration of legality in the Hague Convention, and the international rules of war on seizures, rendered the allegation of an international law violation in Riccmd sufficiently frivolous so that consideration on the merits was unnecessary. The sole question presented in Shapleigh, 299 U. S. 468, concerned the legality of certain action under Mexican law, and the parties expressly declined to press the question of legality under international law. And the Court's language in that case—“For Wrongs of that order the remedy to be followed is along the channels of diplomacy“—must be read against the background of an arbitral“ claims commission that had been set up to determine compensation for cl.i imants in the position of Shapleigh, the existence of which the Court was well aware. “[A] Tribunal is in existence, the International Claims Commission, established by convention between the United States and Mexico, to which the plaintiffs are at liberty and have long ago submitted a claim for reparation.” 299 U. S., at 471.

In the other cases cited in the Court's opinion, ante, p. 17, the act of stale doctrine was not even peripherally involved; the law applicable in both United States v. Belmont, 301 U. S. 324, and United States v. Pink, 315 TJ. S. 203, was a compact between the United States and Russia regarding the effect of Russian nationalization decrees on property located in the United States. No one seriously argued that the act of state doctrine precludes reliance on a binational compact dealing with the effect to be afforded or denied a foreign act of state.

3 An act of state has been said to be any governmental act in which the sovereign's interest qua sovereign is involved. “The expression 'act of state’ usually denotes ‘an executive or administrative exercise of sovereign power by an independent state or potentate, or by its duly authorized agents or officers.’ The expression, however, is not a term of art, and it obviously may, and is in fact often intended to, include legislative and judicial acts such as a statute, decree or order, or a judgment of a superior Court.” Mann, The Sacrosanctity of the Foreign Act of State, 59 L. Q. Rev. 42 (1943).

4 Rabel, The Conflict of Laws: A Comparative Study 30-69 (1958); Ehrenzheig, Conflict of Laws, 607-633 (1962); Rest. (2d ed.) Conflict of Laws §254 (a) (Tent. Draft No. 5 (1959); Baade, Indonesian Nationalizations Measures Before Foreign Courts—A Reply, 54 Am. J. Int'l L. 801 (1960); Re, Foreign Confiscations in Anglo- American Law—A Study of The Rule of Decision Principle 49-50 (1951).

5 See generally, Kaplan and Katzenbach, The Political Foundations of International Law (1961), 135-172; Herz, International Politics in The Atomic Age (1959), 58-62.

6 Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Idemitsu Kosan Kabushiki Kaisha, [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 305 (Tokyo Dist. Ct.) aff'd, [1953] Int'l L. Rep. 312 (Tokyo High Ct.); Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. S. U. P. O. R., [1955] Intl L. Rep. 19 (Ct. of Venice (1953)); Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. S. U. P. O. R., [1955] Int'l L. Rep. 23, 39-43 (Civ. Ct. of Rome 1954); compare N. V. Veraniade Deli-Maatschapijen v. Deutsch- Indonesische Tabak-Handels-gesellschaft (Bremen Court of Appeals), excerpts translated in Domke, Indonesian Nationalization Measures Before Foreign Courts, 54 Am. J. Intl L. 305, 313-314 (1960), with Confiscation of Property of Sudenten Germans Case, [1948] Ann. Dig. 24, 25 (No. 12) (Amstgericht of Dingolfing) (discriminatory confiscatory decrees). See also West Rand Central Gold Mining Co. v. The Kino, [1905] 2 K. B. 391.

7 United States v. Moscow Fire Ins. Co., 280 N. Y. 286 (1938), aff'd, 309 U. S. 624; Vladikavkazsky R. Co. v. New York Trust Co., 263 N. Y. 369; Plesch v. Banque Nationale de la Republique de Haiti, 273 App. Div. 224, aff'd, 298 N. Y. 573; Bollock v. Societe Generate, 263 App. Div. 601; Latvian State Cargo & Passenger S. S. Line v. McGrath, 188 F. 2d 1000 (C. A. D. C. Cir.).

8 Second Russian Ins. Co. v. Miller, 297 F. 404 (C. A. 2d Cir.); James v. Second Russian Ins. Co., 239 N. Y. 248; Sokoloff v. National City Bank, 239 N. Y. 158; A/S Merilaid & Co. v. Chase Nat'l Bank, 189 Misc. 285 (Sup. Ct. N. Y.). See also Compania Ron Bacardi v. Bank of Nova Scotia, 193 F. Supp. 814 (D. C. S. D. N. Y.) (normal conflicts rule superseded by a national policy against recognition of Cuban confiscatory decrees).

Similarly, it has been held that nationalization of shares of a foreign corporation or partnership owning property in the United States will not affect the title of former shareholders or partners; the prior owners are deemed to retain their equitable rights in assets located in the United States. Vladikavkazsky R. Co. v. New York Trust Co., 263 N. Y. 369. The acts of a belligerant occupant of a friendly nation in respect to contracts made within the occupied nation have been denied application in our courts. Aboitii & Co. v. Price, 99 F. Supp. 602 (D. C. Utah). Compare Werfel v. Sirnotenska Banka, 260 App. Div. 747, 752 (N. Y.).

9 See the recent affirmation of this doctrine in Banco do Brasil, S. A. v. Israel Commodity Co., holding that an action by Brazil against a New York coffee importer for fraudulently circumventing Brazilian foreign exchange regulations by forging documents in New York was contrary to New York public policy, notwithstanding that the Bretton Woods agreement, to which both the United States and Brazil are parties, expresses a policy favorable to such exchange laws. 12 N. Y. 2d 371, cert, denied, 375 U. S. 919. See also The Antelope, 10 Wheat. 66, 123; Huntington v. Attrill, 146 U. S. 657; Moore v. Mitchell, 30 F. 2d 600, aff'd on other grounds, 281 U. S. 18; Dicey, Conflict of Laws (Morris ed., 7th ed. 1958), 667; Wolff, Private International Law (2d ed. 1950), 525.

10 Hilton v. Guyot, 159 TJ. S. 113 (lack of reciprocity in the foreign state renders the judgment only prima facie evidence of the justice of the plaintiff's claim); cf. Venezuelan Meat Export Co. v. United States. 12 F. Supp. 379 (D. C. D. Md.); The W. Talbot Dodge, 15 F. 2d 459 (D. C. S. D. N. Y.) (fraud is a defense to the enforcement of foreign judgments), Title Ins. & Trust Co. v. California Development Co., 171 Cal. 173 (fraud); Banco Minico v. Ross. 106 Tex. 522 (procedure of Mexican court offensive to natural justice); De Brimont v. Penniman, 7 Fed. Cas. 309, No. 3, 715 (C. C. S. D. N. Y.) (judgment founded on a cause of action contrary to the “policy of our law, and does violence to what we deem the rights of our own citizen“); other cases indicate that American courts will refuse enforcement where protection of American citizens or institutions require reexamination. Williams v. Armroyd, 7 Cranch 423; McDonald v. Grand Trunk R. Co., 71 N. H. 448; Caruso v. Caruso, 106 N. J. Eq. 130; Hohner v. Gratz. 50 F. 369 (C. C. S. DTN. Y.) (alternative holding). See generally Reese, The Status In This Country of Judgments Rendered Abroad, 50 Col. L. Rev. 783 (1950).

11 The Court attempts to distinguish between these foreign acts on the ground that all foreign penal and revenue and perhaps other public laws are irrebuttably presumed invalid to avoid the embarrassment stemming from examination of some acts and that all foreign expropriations are presumed valid for the same reason. This distinction fails to explain why it may be more embarrassing to refuse recognition to an extraterritorial confiscatory law directed at nationals of the confiscating state than it would be to refuse effect to a territorial confiscatory law. From the viewpoint of the confiscating state, the need to affect property beyond its borders may be as significant as the need to take title to property within its borders. And it would appear more offensive to notions of sovereignty for an American court to deny enforcement of a foreign law because it is deemed contrary to justice, morals, public policy, than to deny enforcement because of principles of international law. It will not do to say that the foreign state has no jurisdiction to affect title to property beyond its borders, since other jurisdictional bases, such as citizenship, are invariably present. But for the policy of the forum state, doubtless the foreign law would be given effect under ordinary conflict principles. Compare Sokoloff v. National City Bank, 234 N. Y. 158; Second Russian Ins. Co. v. Miller, 297 F. 404 (C. A. 2d Cir.) with Werfel v. Sirnostenska Banka, 260 App. Div. 747.

The refusal to enforce foreign penal and tax laws and foreign judgments is wholly at odds with the presumption of validity and requirement of enforcement under the act of state doctrine; the political realms of the acting country are clearly involved, the enacting country has a large stake in the decision, and when enforcement is against nationals of the enacting country, jurisdictional bases are clearly present. Moreover, it is difficult, conceptually or otherwise, to distinguish between the situation where a tax judgment secured in a foreign country against one who is in the country at the time of judgment is presented to an American court and the situation where a confiscatory decree is sought to be enforced in American courts.

12 For the extent to which the Framers contemplated the application of international law in American courts and their concern that this body of law be administered uniformly in the federal courts, see The Federalist: No. 3, at 22 (1 Bourne ed. 1901), by John Jay; No. 80, at 112 and 114; No. 83, at 144 and No. 82 (2 Bourne ed. 1901), by Alexander Hamilton; No. 42, by James Madison.

Thomas Jefferson, speaking as Secretary of State, wrote to M. Genet, French Minister, in 1793: “The law of nations make an integral part of the laws of the land.” I Moore, Digest of International Law (1906), 10. And see the opinion of Attorney General Randolph given in 1792: “The law of nations, although not specially adopted by the Constitution or any municipal act, is essentially a part of the law of the land.” 1 Op. Atty. Gen. 27. Also see Warren, The Making of the Constitution, Pt. I, c. I, at 116: Madison's Notes in 1 Farrand 21, 22, 244, 316. See generally Dickinson, The Law of Nations as Part of the National Law of the United States,. 101 XT. of Pa. L. Rev. 26 (1952).

13 This intention was reflected and implemented in the Articles of the Constitution. Art. I, § 8 empowers the Congress “to define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations.” Article III, §2 extends the judicial power “to all CBSes, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;—to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;—to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;—to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;—to Controversies between two or more States;— between a State and Citizens of another State;—between Citizens of different States;—between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, citizens or subjects.“

14 As early as 1793, Chief Justice Jay stated in Chisholm v. Georgia that “Prior… to that period [the date of the Constitution], the United States had, by taking a place among the nations of the earth, become amenable to the law of nations.” 2 Dall. 419, at 474. And in 1796, Justice Wilson stated in Ware v. Hylton: “When the United States declared their independence, they were bound to receive the law of nations in its modern state of purity and refinement.” 3 Dall. 199, at 281. Chief Justice Marshall was even more explicit in The Nereide, when he said:

“If it be the will of the government to apply to Spain any rule respecting systems which Spain is supposed to apply to us, the government will manifest that will by passing an act for the purpose. Till such an act be passed, the Court is bound by the law of nations which is part of the law of the land.” 9 Cranch 388, at 423.

As to the effect such an Act of Congress would have on international law, the Court has ruled that an act of Congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations if any other possible construction remains. MacLeod v. United States, 229 U. S. 416, 434 (1913).

As was well stated in Hilton v. Guyot:

“International law, in its widest and most comprehensive sense— including not only questions of right between nations, governed by what has been appropriately called the law of nations'; but also questions arising under what is usually called private international law or the conflict of laws, and concerning the rights of persons within the territory and dominion of one nation, by reason of acts, private or public, done within the dominions of another nation—is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice, as often as such questions are presented in litigation between man and man, duly submitted to their determination.

“The most certain guide, no doubt, for the decision of such questions is a treaty or a statute of this country. But when, as is the case here, there is no written law upon the subject, the duty still rests upon the judicial tribunals of ascertaining and declaring what the law is, whenever it becomes necessary to do so, in order to determine the rights of parties to suits regularly brought before them. In doing this, the courts must obtain such aid as they can from judicial decisions, from the works of jurists and commentators, and from the acts and usages of civilized nations.” 159 U. S. 113, 163 (1895). For other cases which explicitly invoke the principle that international law is a part of the law of the land, see, for example: Talbot v. Janson, 3 Dall. 133, 161; Respublica v. DeLongchamps, 1 Dall. Ill, 116; The Rapid, 8 Cranch 155, 162; Freemont v. United States, 17 How. 542, 557; United States v. Arjona, 120 U. S. 479.

15 Among others, international law has been relied upon in cases concerning the acquisition and control of territory, Jones v. United States, 137 TJ, S. 202; Mormon Church v. United States, 136 U. S. 1; Dorr v. United States, 195 TJ. S. 138; the resolution-^ boundary disputes, Iowa v. Illinois, 147 U. S. 1; Arkansas v. Tennessee, 246 TJ. S. 158; in cases involving questions of nationality, United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 168 U. S. 649; Inglis v. The Trustees of the Sailors Snug Harbour, 3 Pet. 99; principles of war and neutrality and their effect on private rights, The S. S. Appam, 243 U. S. 124; Dow v. Johnson, 100 TJ. S. 158; Ford v. Surget, 97 TJ. S. 594; and cases involving private property rights generally, The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon, 7 Cranch 116; United States v. Percheman, 7 Pet. 51.

16 [Discriminatory laws enacted out of hatred, against aliens or against persons of any particular race or category or against persons belonging to specified social or political groups … run counter to the internationally accepted principle of the equality of individuals before the law.” Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. S. V. P. 0. R. Co., [1955] Int'I L. Rep. 23, 40 (Civ. Ct. of Rome 1954); see also Friedman, Expropriation In International Law (1953), 189-192; Wortly, Expropriation In Public International Law (1959), 120-121; Cheng, The Rationale of Compensation for Expropriation, 44 Transact. Grot. Soc'y 267, 281, 289 (1959); Seidl-Hohenveldern, Title to Confiscated Foreign Property and Public International Law, 56 Am. J. Int'I L. 507, 509-510 (1962).

17 In the only reference in the Court's opinion to fairness between the litigants, and a court's obligation to resolve disputes justly, ante, p. 35, the Court quickly disposes of this consideration by assuming that the typical act of state case is between an original owner and an “innocent” purchaser, so that it is not unjust to leave the purchaser's title undisturbed by applying the act of state doctrine. Beside the obvious fact that this assumption is wholly inapplicable to the case where the foreign sovereign itself or its agent seeks to have its title validated in our courts—the case at bar—it is far from apparent that most cases represent suits between the original owner and an innocent purchaser. The “innocence” of a purchaser who buys goods from a government with knowledge that possession or apparent title was derived from an act patently in violation of international law is highly questionable. More fundamentally, doctrines of commercial law designed to protect the title of a bona fide purchaser can serve to resolve this question without reliance upon a broad irrebuttable presumption of validity.

18 Another situation was also presented by the Nazi decrees challenged in the Bernstein litigation; these religious expropriations, while involving nationals of the foreign state and therefore customarily not cognizable under international law, had been condemned in multinational agreements and declarations as crimes agajnst humanity. The acts could thus be measured in local courts against widely held principle rather than judged by the parochial views of the forum.

19 The Court argues that an international law exception to the act of state doctrine would fail to deter violations of international law, since judicial intervention would at best be sporadic. At the same time, proceeding on a contradictory assumption as to the impact of such an exception, the Court argues that the exception would render titles uncertain and upset the flow of international trade. The Court attempts to reconcile these conclusions by distinguishing between “direct” and “indirect” impacts of a declaration of invalidity, and by assuming that the exporting nation need only find other buyers for its products at the same price. From the point of view of the exporting nation, the distinction between indirect and direct impact is meaningless, and the facile assumption that other buyers at the same price are available and the further unstated assumption that purchase price is the only pertinent consideration to the exporting country are based on an oversimplified view of international trade.

There is no evidence that either the absence of an act of state doctrine in the law of numerous European countries or the uncertainty of our own law on this question until today's decision has worked havoc with titles in international commerce or presented the nice questions the Court sets out on p. 34, n. 40, ante, or has substantially affected the flow of international commerce.

20 These issues include whether a foreign state exists or is recognized by the United States, Gehton v. Hoyt, 3 Wheat. 246; The Sapphire, 11 Wall. 164, 168, the status that a foreign state or its representatives shall have in this country (sovereign immunity); Ex parte Muir, 254 U. S. 522; Ex parte Peru, 318 U. S. 578, the territorial boundaries of a foreign state; Jones v. United States, 137 U. S. 202, and the authorization of its representatives for state-to-state negotiation. Ex parte Hitz, 111 U. S. 776; In re Baiz, 135 U. S. 403.

2l “[T]he Government of the United States considers this law to be manifestly in violation of these principles of international law which have long been accepted by the free countries of the West. It is in its essence discriminatory, arbitrary and confiscatory.” Press Release No. 397, Dept. of State, July 16, 1960.

The United States Ambassador to Cuba condemned this decree, stating to the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Relations:

“Under instructions from my government, I wish to express to Your Excellency the indignant protest of my government against this resolution and its effects upon the legitimate rights which American citizens have acquired under the laws of Cuba and under International Law.” Press Release No. 441, Dept. of State, Aug. 9, 1960.

* [Final print will be corrected to read “international.“]

22 The Court disclaims saying that there is no governing international standard in this area, but only that the matter is not meft for adjudication. Ante, p. 29, n. 27. But since the Court's view is that there are only the divergent views of nations that subscribe to different ideologies and practical goals on “expropriations,” the matter is not meet for adjudication, according to the Court, because of the lack of any agreement among nations on standards governing expropriations, i. e., there is no international law in this area, but only the political views of the political branches of the various nations.

These assertions might find much more support in the authorities relied on by the Court and others if the issue under discussion was not the undefined category—expropriation—but the clearly discreet issue of adequate and effective compensation. It strains credulity to accept the proposition that newly emerging nations or their spokesmen denounce all rules of state responsibility—reject international law in regard to foreign nationals generally—rather than reject the traditional rule of international law requiring prompt, adequate, and effective compensation.

23 There is another implication in the Court's opinion: the act of state doctrine applies to all expropriations, not only because of the lack of a consensus among nations on any standards but because theissue of validity under international law “touches … the practical and ideological goals of the various members of the community of nations.” If this statement means something other than that there is no agreement on international standards governing expropriations, it must mean that the doctrine applies because the issue is important politically to the foreign state. If this is what the Court means, the act of state doctrine has been expanded to unprecedented scope. No foreign act is subject to challenge where the foreign nation demonstrates that the act is in furtherance of its practical or ideological goals. What foreign acts would not be so characterized?

24 “A refusal of courts to consider foreign acts of, state in the light of the law of nations is not … merely a neutral doctrine of abstention. On the contrary the effect of such a doctrine is to lend thefull protection of the United States courts, police, and governmental agencies to commercial or property transactions which are contrary to the minimum standard of civilized conduct … . ‘ * “ The Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Committee on International Law, A Reconsideration of the Act of State Doctrine In United States Courts (1959), 8.

25 That embarrassment results from a rigid rule of act of state immunity is well demonstrated by the judicial enforcement of German racial decrees after the war. The pronouncements by United States courts that these decrees vest title beyond question was wholly at odds with the executive's official policy, embodied in representations to other governments, that property taken through racial decrees by the Nazi Government should be returned to original owners and thus not be subject to reparation claims. Compare statements by Secretary of State Marshall, reprinted in 16 Dept. State Bull. 653, 793 (1947), with Bernstein v. Van Heyghen Freres Societe Anonyme, 163 F. 2d 246 (C. A. 2d Cir.). This embarrassing divergence of governmental opinion was eliminated only after the executive intervened and requested the courts to adjudicate the matter on the merits. Bernstein v. Nederlondschi-Amerilccuinsche, Stoomvart- Maatschappij, 210 F. 2d 375 (C. A. 2d Cir.).

26 It is difficult to reconcile the Court's statement that rules pertaining to expropriations are unsettled or unclear with the Court's pronounced desire to avoid making any statements on the proper or accepted principles of international law, lest it embarrass the executive, who may have a different view in respect to this particular expropriation or this particular expropriating country. Is not the Court's limitation of the act of state doctrine to the area of expropriations— based upon the uncertainty and fluidity of the governing law in this area—an admission that may prove to be embarrassing to the executive at some later date ? And the very line drawing that the Court stresses as potentially disruptive of the executive's conduct of foreign affairs is inevitable under the Court's approach, since subsequent cases not involving expropriations will require us to determine if the act of state doctrine applies and the Court's standard is the strength and clarity of the principles of international law thought to govern the issue. Again our view of the clarity of these principles and the extent to which they are really rules of international law may not be identical with the views of the Department of State. These are some of the inherent difficulties of establishing a rule of law on the basis of speculations about possible but unidentified embarrassment to the executive at some unknown and unknowable future date.

27 The procedure was instituted as far back as The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon, 7 Cranch 116 (1812), when a United States Attorney, on the initiative of the Executive Branch, entered an appearance in a case involving the immunity of a foreign vessel, and was further denned in Ex parte Muir, 254 U. S. 522, 533 (1920), when the Court stated that the request by the foreign suitor to the executive department was an acceptable and well-established manner of interposing a claim of immunity. Under the procedure outlined in Muir each of the contesting parties may raise the immunity issue by obtaining an official statement from the State Department, or by encouraging the executive to set forth appropriate suggestions to the Court through the Attorney General. See Compania Espanola de Naveqacion Maritima, S. A. v. The Novemar, 303 U. S. 68, 74. See generally Dickinson, The Law of Nations As'National Lawr “Political Questions,” 104 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 451, 470-475 (1956).