No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

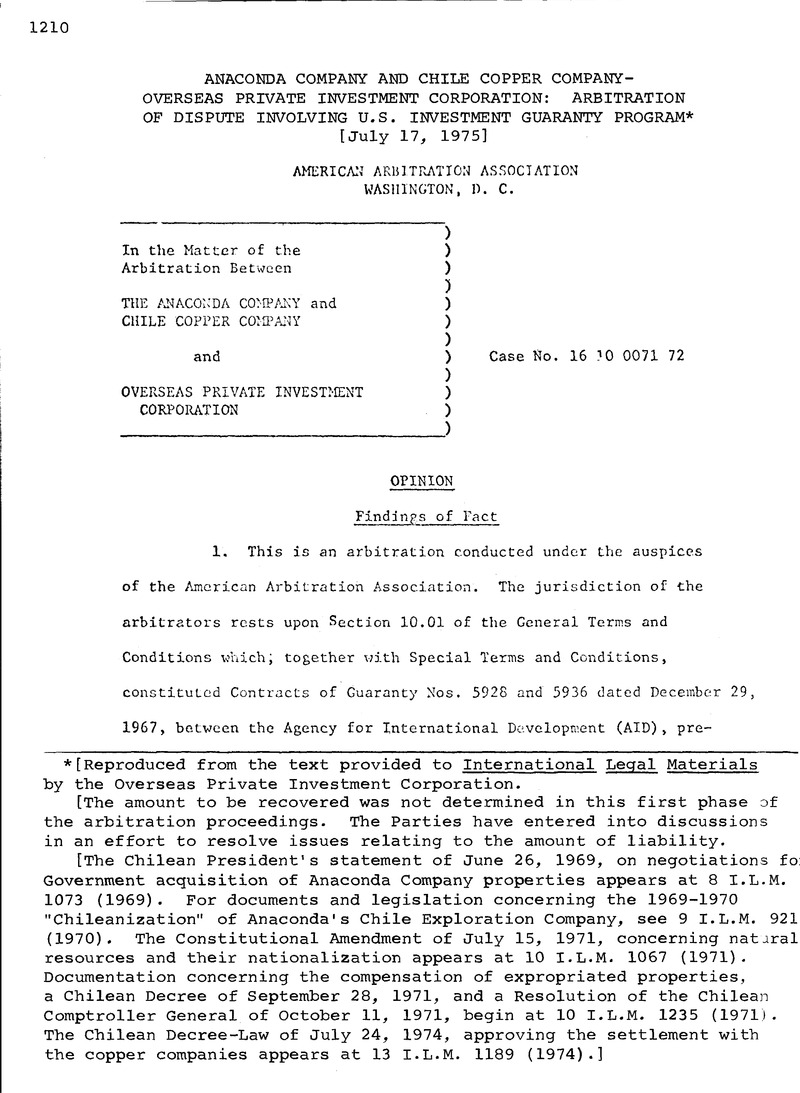

Anaconda Company and Chile Copper Company-Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Arbitration of Dispute Involving U.S. Investment Guaranty Program*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1975

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Over seas Private Investment Corporation.

[The amount to be recovered was notde termined in this first phase of the ar bitration proceedings. The Parties have entered into discussions in an effort to resolve issues relating to the amount of liability.

[The Chilean President's statement of June 26, 1969, on negotiations fo: Government acquisition of Anaconda Company properties appears at 8 I.L.M. 1073 (1969) .For documents and legislation concerning the 1969-1970 “Chileanization” of Anaconda's Chile Exploration Company, see 9 I.L.M. 921 (1970). The Constitutional Amendment of July 15, 1971, concerningnatural resources and the irnational ization appears at 10 I.L.M . 1067 (1971) .Documentation concerning the compensation of expropriated properties, a Chilean Decree of September 28 , 1971, and a Resolution of the Chilean Compt roller General of October 11 ,1971 ,beginat 10 I.L.M. 1235 (1971). The Chilean Decree-Law of July 24, 1974, approving the settlement with the copper companies appear sat 13 I.L.M. 1189 (1974).]

References

1/ That submission to arbitration is authorized by §635(i) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, 22 U.S.C. §2395(i).

2/ Exhibits presented by Claimant commence with numbers whereas Respondent's Exhibits commence with letters. Testimony is referred to by transcript page, e.g., (Tr. ).

3/ Except for ]0 shares of the stdck of Chilex held directly by The Anaconda Company (Ex. 5(a) (b).B).

4/ The history of these programs can be traced in Clubb & Vance, Incentives to Private U.S. Investment Abroad under the Foreign Assistance Program,72 Yale L.J. 475 (1963); Ray, Evolution, Scope and Utilization of Guarantees of Foreign Investments, 21 Bus. Law 1051 (1966).

5/ These requirements relate to such matters as the American nationality of the investor and the existence of an agreement or arrangement between the United States and the host government. The latter requirement was regarded as satisfied by AID with respect to Chile although the protocol as to expropriation was never ratified. (Exs. 7.A, 7.B, 7.C).

6/ At the date of the Contracts of Guaranty the relevant revision was that of October 1966, (Ex, K.5)

7/ But for the waiver letters Anaconda's investments would not have been eligible for guaranty as not being any longer “new” investments when the formal contracts came up for signature.

8/ Citations herein are to a final, definitive, text enacted on May 15, 1967 as Law No. 16,624 which integrated the provisions of the anuary 25, 1966 Law (No. 16,425) as well as prior and subsequent legislation. (Ex. 15-17.B) .

9/ The Bradon Contract appears as Ex. 19.A, the Cerro Contract as Ex. 19.B and the Anaconda-Exotica as Ex. L.l

10/ Initial capitals indicate defined terms.

11/ Section 1.30 of the General Terms and Conditions defines “Project” as meaning “the economic activity of the Foreign Enterprise resulting in whole or in part from the Investment.The Project is more fully described in the Special Terms and Conditions.”

12/ Except for 10 shares owned by The Anaconda Company.

13/ The related term “Date of Expropriation” is defined in Section 1.12 as “the first day of the period in which an action through duration became Expropriatory Action, as defined in Section 1.15.”

14/ OPIC states that this application of standby coverage to amounts already invested, rather than to future investments, was unintended and its consequences unforeseen. However, it does not claim that this use of standby coverage was illegal or improper in this case (Ex, L.5, pp. 43-4). The contract forms have subsequently been changed.

15/ We defer to the “Discussion and Conclusions” the question of what sort of “control” Anaconda might need to retain in order that its investment might remain within the scope of the Guaranty Contracts.

16/ The previous reported arbitration awards under the expropriation guaranty program are: the International Telephone & Telegraph Corporation, Sud America, case, 13 Int. Leg. Mat. 1307 (1974); the International Bank of Wash, case, 11 Int.. Leg. Mat. 1216 (1972); the Valentine Petroleum & Chen. Corp. case, 9 Int. Leg. Mat. 889 (1967). See generally, Adams, The Emerging Law of Dispute Settlement under the United States Investment Insurance Program, 3 Law & Pol. in Int. Bus. 101 (1971).

17/ See, e.g.,D'Oench, Duhme & Co. v. FDIC, 315 U.S. 447 (1942).

18/ In Standard Oil Co.v. United States, 267 U. S. 76, 79 (1925), the Court said “/w_/hen the United States went into the insurance business, issued policies in familiar form and provided chat in case of disagreement it might be sued, it must be assumed to have accepted the ordinary incidents of suits in such business.”

19/ S. Rep. No. 93-676, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. (1974) at Pt IV.F.1.

20/ In United States v. Seckinger, 397 U.S. 203, 210 (1970) the majority states:

“In fashioning a federal rule we are, of course, guided by the genera.lt principles that have evolved concerning the interpretation of contractual provisions such as that involved here. Among these principles is the general maxim that a contract should be construed most strongly against the drafter, which in this case was the United States.”

The dissent (at pp. 221-23) stated the point even more strongly:

“Even in the domain of private contract law, the author of a standard-form agreement is required to state its terms with clarity and candor. Surely no less is required of the United States of America when it does business with its citizens.

Mr. Justice Holmes once said that ‘/m_/en must turn square corners when they deal with the Government.’ I had always supposed this was a two-way street. The Government knows how to write an indemnification clause when that is what it wants. It has not written one here /footnotes omitted/.”

On the construction of insurance contracts generally, see R. Kecton, Basic Text on Insurance Lav; 68-69, 348-357 (1971).

21/ Vernon, Sovereignty at Pay 46-53 (1971); Symposium, Mining the Resources of the Third World, Proceedings of the 67th Ann. Meeting of the Am. Soc'y Int. L. 227 (1973).

22/ We note in this connection that the definition of Expropriatory Action (Section 1.15) speaks in practical not legalistic terms. The test of Section 1.15 (d) is not whether government action affects legal relationships but whether it “directly results in preventing . . . the Investor from exercising effective control . . or from constructing the Project or operating the same.”

23/ A similar construction was made by contract provision in the Kennecott (Braden) case (Ex. 19.A). As to statutory policy, see Specific Risk Investment Guaranty Handbook, p. 12 (Ex. K.5)

24/ Memorandum on Chilean Law Questions prepared by Sergio Gutierrez Olivos and Manuel Vargas Vargas.