No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

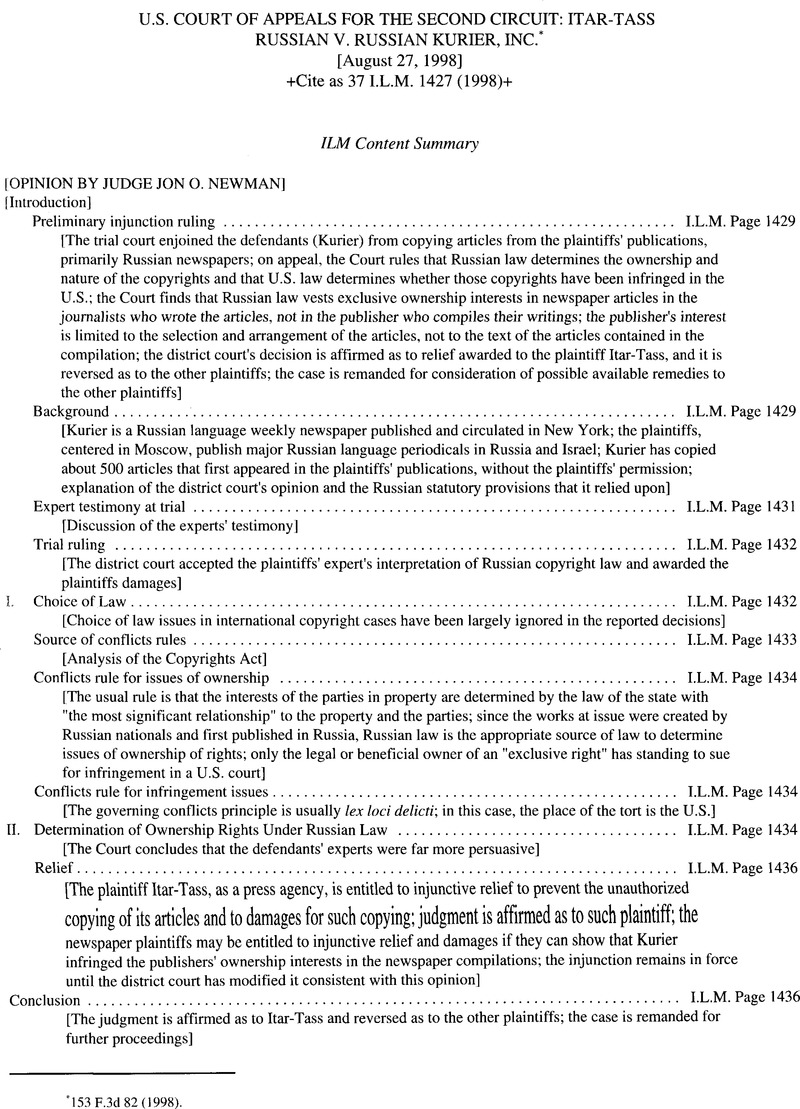

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit: Itar-Tass Russian v. Russian Kurier, Inc.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1998

References

* 153F.3d82(1998).

* [The Judgment is affirmed as to Itar-Tass and reversed as to the other plaintiffs; the case is remanded for further proceedings]

[1] Judge Calabresi was originally a member of the panel, but recused himself after oral argument. Thereafter, Judge Newman was assigned to the panel and has heard the audiotapes of the oral argument.

1 The Newton Davis translation, which was an exhibit at trial, renders this word “publisher.”.

2 The question posed was: Under Russian jurisprudence, must the newspaper be completely copied by infringers of copyright in order for the publisher to have standing to come to court, or does the publisher have the right to come to court even in the case where the copyrights have been infringed by means of a reprint of just one or two articles by third parties (infringers)?

3 Prof. Patry, a faculty member at Cardozo Law School, has served as Adviser to the Register of Copyrights and Counsel to the Subcommittee on Intellectual Property and Judicial Administration of the Committee on the Judiciary of the U.S. House of Representatives. He is the author of well known treatises on copyright law. See William F. Patry, Copyright Law and Practice (1994); William F. Patry, The Fair Use Privilege in Copyright Law (2d ed. 1995).

4 Though Aldon's use of the “actual supervision and control” test for applying the work-for-hire doctrine has since been rejected, see Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989), its use of U.S. law as the source of the work-for-hire doctrine remains unimpaired, though the precedential force of the implicit conflicts ruling is weakened by the absence of any discussion of the issue. Under principles we discuss below, United States law was properly applied to the ownership issue since the country of origin of the work was the United States, the work having been first published in the United States and “authored” by a U.S. citizen.

5 To the extent that this decision applied the U.S. work-for-hire doctrine simply because copyright certificates had been issued by the United States Copyright Office, it relied on an unpersuasive ground. Issuance of the certificate is not a determination concerning applicability of the work-for- hire doctrine or a resolution of any issue concerning ownership. See Jane C. Ginsburg, Ownership of Electronic Rights and the Private International Law of Copyright, 22 Colum.-VLA J.L. & Arts 165, 171 n.22 (1998).

6 See Berne Convention Art. 5(1) (Paris text 1971), reprinted in 3 William F. Patry, Copyright Law and Practice 2013 (1994).

7 See Universal Copyright Convention (Paris text 1971), reprinted in 3 William F. Patry, Copyright Law and Practice 2054 (1994).

8 Prof. Patty's brief, as Amicus Curiae, helpfully points out that the principle of national treatment is really not a conflicts rule at all; it does not direct application of the law of any country. It simply requires that the country in which protection is claimed must treat foreign and domestic authors alike. Whether U.S. copyright law directs U.S. courts to look to foreign or domestic law as to certain issues is irrelevant to national treatment, so long as the scope of protection would be extended equally to foreign and domestic authors.

9 Other pertinent provisions are: Section 2(2), which provides: “The obligations of the United States under the Berne Convention may be performed only pursuant to appropriate domestic law.” Section 3(a)(2), which provides: “The provisions of the Berne Convention … shall not be enforceable in any action brought pursuant to the provisions of the Berne Convention itself.” Section 3(b)(l), which provides: “The provisions of the Berne Convention … do not expand or reduce the right of any author of a work, whether claimed under Federal, State, or the common law … to claim authorship of the work.“

10 The recently added provision concerning copyright in “restored works,” those that are in the public domain because of noncompliance with formalities of United States copyright law, contains an explicit subsection vesting ownership of a restored work “in the author or initial rightholder of the work as determined by the law of the source country of the work.” 17 U.S.C. § 104A(b) (emphasis added); see id. § 104A(h)(8) (defining “source country“).

11 This provision could be interpreted to be an example of the general conflicts approach we take in this opinion to copyright ownership issues, or an exception to some different approach. See Jane C. Ginsburg, Ownership of Electronic Rights and the Private International Law of Copyright, 22 Colum.- VLA J.L. & Arts 165, 171 (1998). We agree with Prof. Ginsburg and with the amicus, Prof. Patry, that section 104A(b) should not be understood to state an exception to any otherwise applicable conflicts rule. See Ginsburg, id.; Brief for Amicus Curiae at 14-17. In deciding that the law of the country of origin determines the ownership of copyright, we consider only initial ownership, and have no occasion to consider choice of law issues concerning assignments of rights.

12 The Berne Convention expressly provides that “[o]wnership of copyright in a cinematographic work shall be a matter for legislation in the country where protection is claimed.” Berne Convention, Art. 14to(2)(a). With respect to other works, this provision could be understood to have any of three meanings. First, it could carry a negative implication that for other works, ownership is not to be determined by legislation in the country where protection is claimed. Second, it could be thought of as an explicit assertion for films of a general principle already applicable to other works. Third, it could be a specific provision for films that was adopted without an intention to imply anything about other works. In the absence of any indication that either the first or second meanings were intended, we prefer the third understanding.

13 Newcity sought to analogize the exclusive rights that he believed were held by both the newspaper and the author to the rights held jointly by co-authors. Russian copyright law, however, like similar provisions elsewhere, recognizes jointly held rights in “a work that is the product of the joint creative work of two or more persons.” Russian Copyright Law, Art. 10(1). In the absence of either joint authorship or contractual arrangements, it would be most unusual to have exclusive rights held by anyone other than the author.

14 Also unpersuasive in the opinion of an arbitration court of the Altai Region of Russia, Closed Stock Company Komsomolskaya Pravda v.Limited Liability Company RIA Nasha Pressa, Case # 235/98-10 (City of Barnaul, Russian Federation, Feb. 25, 1998), which awarded damages to a newspaper for another publication's reprinting of two articles from the newspaper. The opinion of the arbitration court (furnished to us by the appellees) deems exclusive rights in the articles to be owned by the newspaper by virtue of Article 14(2) of the Russian Copyright Law, ignoring the provision of Article 14(4), which renders Article 14(2) inapplicable to newspapers. 1

15 Though the complaint does not precisely plead infringement of compilation rights, it does allege that the newspapers have rights “in the newspapers,” Complaint ¶ 22, and that the defendants have copied “numerous items of Plaintiffs’ Subject Works,” id. ¶ 28. Moreover, when, during the trial, counsel for the defendants objected to a question concerning the “appearance” of some copied text on the ground that “[t]here is no allegation[] in this case about the creative appearance being infringed,” counsel for the plaintiffs replied, “That is, indeed, one of our central arguments.“

16 Moreover, though the parties do not raise the issue, we may assume that the authors of the articles, by submitting them to their newspaper publishers, gave the publishers an implied license to use the articles in the newspaper compilations. That non-exclusive license, of course, does not entitle the publishers to sue in the United States for infringement of the articles as such.

17 Upon remand, the District Court will also have to consider, if the claim is pursued, what relief might be accorded to plaintiff-appellee Heslin Trading Ltd., the publisher of Balagan, a Russian language comic magazine published monthly in Israel. What ownership interests Heslin might have, under Israeli law, that have been infringed, under United States law, by Kurier's copying was not explicitly considered by the District Court. While this appeal was pending, we received a motion from Al J. Daniel, Jr., seeking to intervene in support of the judgment in order to protect the value of a charging lien he asserts as former counsel for the plaintiffs. See Itar- Tass Russian News Agency v. Russian Kurier, Inc., 140 F.3d 442 (2d Cir. 1998). We deny the motion to intervene, without prejudice to renewal in the District Court on remand.