No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

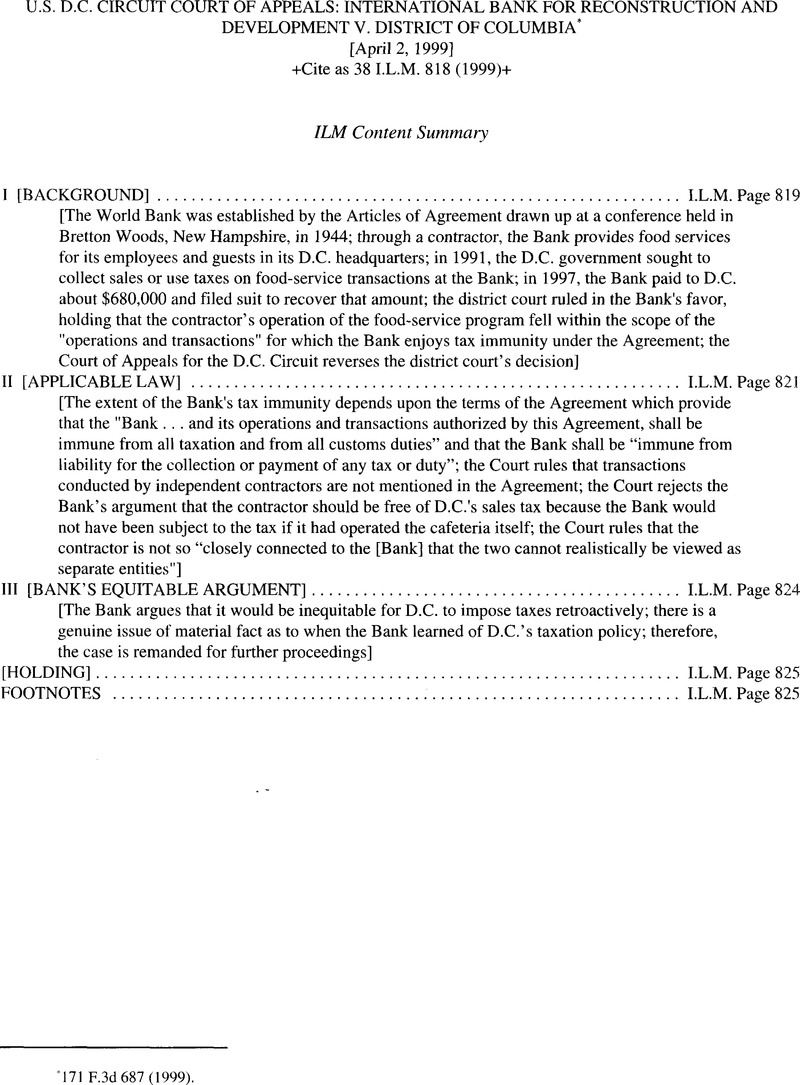

United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development v. District of Colombia

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1999

References

* 1VI F.3d 687 (1999).

1 The record does not disclose whether the Bank actually received any profits for the years covered by the Gardner Merchant contract.

2 The District makes nothing of the point that although the Bank paid the taxes and is suing to recoup its payment, the Bank itself incurred no liability under District law.

3 Although the Gardner Merchant contract contains much detail about the nature of the food program and allows the Bank to monitor closely for compliance, these contractual provisions do not affect our view that the contractor is independent of the Bank.

4 In May 1997, the U.S. State Department informed the District by letter of the government's view that imposing the disputed taxes retroactively would be “inequitable and inconsistent with” Article VII, § 9. The idea appeared to be that the Bank had been lulled into believing that its contractor had tax immunity and so had agreed to hold Gardner Merchant harmless from tax liability. The letter concluded that it was “without prejudice to the views of the United States Government with respect to the question of whether the prospective collection of sales tax by a World Bank contractor from Bank staff and guests who do not enjoy personal sales-tax privileges is permissible under the Articles of Agreement.” Although the United States filed an amicus brief in the district court taking the same position, it has not presented its views to this court.

5 We also place no weight on the statement of the New York Department of Taxation and Finance that if the World Bank had an independent contractor operate a cafeteria for it within the headquarters of the United Nations, food sales would be subject to New York state and local sales tax.

6 Section 9(b) of the Act then provided that “[t]he Commission, and the property, activities, and income of the Commission, are hereby expressly exempted from taxation in any manner or form by any State….” Carson, 342 U.S. at 233.

7 The Bank attempts to broaden the reach of Carson by arguing that its outcome did not depend upon the Atomic Energy Act's express provision for the use of independent contractors. We disagree with such a reading. The Carson Court rested its decision precisely on that ground. As the Court interpreted the Act, Congress anticipated that the Commission would perform its functions through independent contractors. See id. at 236.

8 Graves v. New York ex rel. O'Keefe, 306 U.S. 466, 489 (1939) (Frankfurter, J., concurring).

9 The tax immunity of international organizations is based on a principle analogous to the one upon which Chief Justice Marshall relied in McCulloch-to protect against the destructive power of state interference. See, e.g., Broadbent, 628 F.2d at 34 (“[I]nternational organizations must be free to perform their functions and … no member state may take action to hinder the organization.“)

10 The Bank does not contend that the District's sales and use taxes are discriminatory.