To the Editor—In recent years, the most prevalent organisms isolated from inpatients in Brazilian hospitals have had a carbapenem-resistant profile; they are mostly Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) producers.Reference Rodrigues Perez 1 , Reference Rodrigues Perez and Dias 2 One report suggests that >80% of nosocomial infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae are attributable to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPC-Kp), especially in more critical care settings such as intensive care units (ICUs).Reference Rodrigues Perez 1 , Reference Perez, Rodrigues and Dias 3 Their presence and persistence in these environments are correlated with a clinical decline of infected patients that, despite treatment with antimicrobial drugs, are seldom eradicated from the clinical site of infection or colonization because the bulk of therapeutic options are increasingly scarce.

KPC-producing organisms are often resistant to a broad range of antibiotics beyond the β-lactams. In fact, the plasmids that carry the KPC gene may also contain genes encoding enzymes or other mechanisms, often resulting in reduced susceptibility to distinct antimicrobial classes such as fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides among others. Many treatments of KPC infections have employed tigecycline, polymyxins (polymyxin B or colistin), or also a combination of these. Varying outcomes have been reported.Reference van Duin, Kaye, Neuner and Bonomo 4

Therefore, establishing the resistance profile for these isolates is crucially important not only for monitoring but also for implementing infection control measures and for better management of antibiotic therapy. A survey of KPC-Kp isolates from hospitalized patients was performed to provide an indicator of the prevalence of resistance to 4 potential antimicrobial agents widely used for the treatment of KPC-producing organism.

Enterobacterial isolates were recovered from inpatients between January 1 and December 26, 2016, at a tertiary hospital in Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil. Biochemical tests using a MicroScan automated system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) were used to identify enterobacterial species and to determine the susceptibility profiles to amikacin (AK), fosfomycin (FOT), and tigecycline (TGC), and polymyxin B (PMB) was confirmed using E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Selected Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates confirmed with reduced susceptibility to any carbapenem agent were then tested using a synergistic test applying phenyl-boronic acid to detect KPC (isolates included in this study). No attempt was made to select the KPC-Kp isolates based on their first or subsequent recovery because we aimed to detect a possible development of resistance, although KPC-Kp might have been recovered more than once over this period from the same patient.

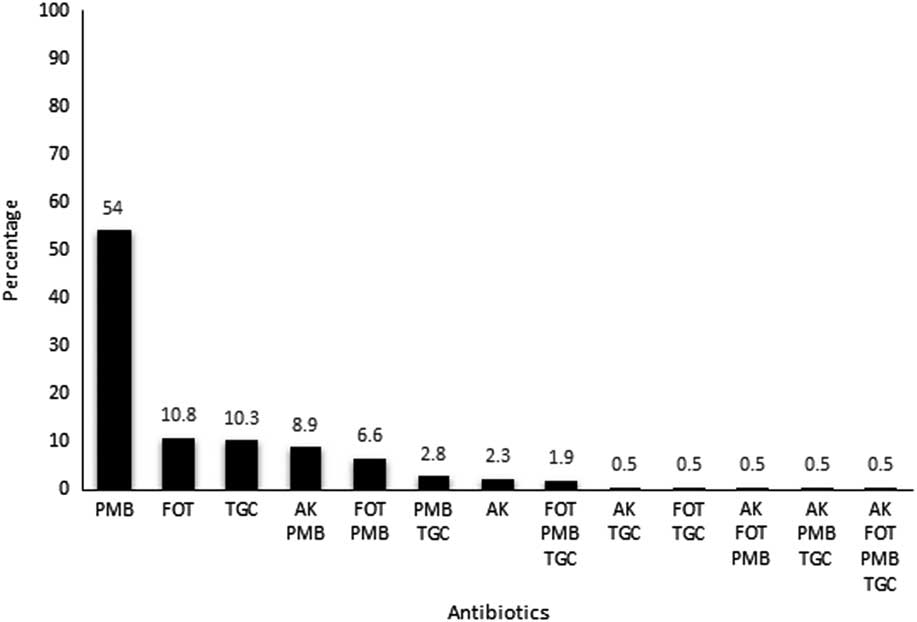

A total of 440 isolates were identified as KPC-Kp during the study period. According to antimicrobial susceptibility testing results, PMB was the least active antibiotic against the panel of isolates (ie, 161 of the 440 isolates [36.6%] were resistant) followed by far by FOT (44 isolates [10%] were resistant), AK (17 isolates [3.9%] were resistent), and TGC (10 isolates [2.3%] were resistant). A minor proportion of isolates displayed intermediate susceptibility to TGC (26 isolates [5.9%] were resistant) and AK (11 isolates [2.5%] were resistant). A little more than half of the KPC-Kp isolates (227 isolates [51.6%]) presented a “multisusceptible” profile, indicating susceptibility to the 4 antimicrobial agents tested in this survey. The remaining 213 isolates were resistant to at least 1 tested antimicrobial agent, and outstanding single resistance to PMB (115 of these 213 isolates [54%]) was the most prevalent resistance profile among the KPC-Kp isolates (Figure 1). Despite this drastic scenario, only 1 isolate was resistant to all 4 antibiotics tested.

Figure 1 Percentage distribution of antimicrobial resistance patterns of KPC-Kp from inpatients during the study period.

Admittedly, there was no cross resistance among the antibiotics tested. Notably, however, the PMB-resistant phenotype, including a single resistance or associated with other agent(s), was the most prevalent phenotype among KPC-Kp isolates identified in this study (54% for single resistance and 75.7% for associated resistance).

Because therapeutics against gram-negative bacilli are scarce and the emergence of this resistance mechanism is a concern, all available options that still show some degree of susceptibility should be strictly monitored. Among the antibiotics evaluated in this survey, PMB has been more widely used than the others. FOT, despite its emergence resistance among KPC-Kp,Reference Perez 5 still showed a low resistance rate; however, its application has been restricted to treating lower urinary tract infections. In addition, despite the current low resistance rates presented to AK and TGC, only in some specific site-related infections has their effectiveness been proven. Thus, as previously shown, the high rate of PMB-resistance seems to be independently associated with its use in clinical practice.Reference Rodrigues Perez and Dias 2 , Reference Giacobbe, Del Bono and Trecarichi 6

KPC production is a major clinical and public health problem in Brazil because it has been increasingly reported and poses a challenge to antimicrobial therapy. This survey described the emergence of KPC-Kp with a PMB-resistance phenotype as a major disseminated pattern in a tertiary-care hospital in Southern Brazil. Failure to reduce the rates of PMB-resistant isolates is worrisome because it may lead to an endemic presence of this phenotype. Measures to control the spread of KPC-mediated resistances, especially those driven by prior exposition as appears to occur with PMB in this study, are urgently needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support: No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest: The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.