To the Editor—Especially for cancer patients, there are multiple coexisting definitions for central venous catheter (CVC)–related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs). Therefore, it is difficult to make comparisons across studies. Furthermore, a considerable number of publications (39 of 190, 21%) did not report the CRBSI definition or cite a reference for the used definition. Reference Tomlinson, Mermel, Ethier, Matlow, Gillmeister and Sung1 To complicate matters further, guidelines on diagnosis of CRBSIs are subject to change over time. Reference Mermel, Farr and Sherertz2,Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza3 For example, in 2003, the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (AGIHO) proposed to distinguish definite (dCRBSIs), probable (pCRBSIs), and possible (possCRBSIs) CRBSIs. Reference Fätkenheuer, Buchheidt and Cornely4 Although these terms are still part of their current guideline, the exact definitions have been adjusted slightly over the years. Reference Wolf, Leithauser and Maschmeyer5,Reference Hentrich, Schalk and Schmidt-Hieber6 In addition, dCRBSIs and pCRBSIs are often combined (dpCRBSIs) for reporting purposes. Reference Schalk, Teschner and Hentrich7,Reference Biehl, Huth and Panse8

Recently, we provided comparative epidemiological data on CRBSIs from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and a registry study in high-risk patients with hematological malignancies. Reference Schalk, Teschner and Hentrich7 In the RCT data set, the 2008 AGIHO definitions for CRBSIs were initially used, Reference Wolf, Leithauser and Maschmeyer5 whereas the registry applied the 2012 AGIHO definitions. Reference Hentrich, Schalk and Schmidt-Hieber6 The 2 guidelines differ in their definition of pCRBSIs and possCRBSIs. In brief, criteria for pCRBSIs and possCRBSIs are more strict in the newer guideline (see Supplementary Table S1 for a detailed comparison). Because end points in the RCT Reference Biehl, Huth and Panse8 referred to the 2008 definitions, the underlying data were reassessed according to the 2012 definitions to ensure comparability of the 2 data sets. Reference Schalk, Teschner and Hentrich7

The question thus arises: To what extent do different CRBSI definitions influence reported CRBSI epidemiology? Therefore, in this study, we compared the epidemiological data of CRBSIs of the aforementioned RCT once using the 2008 definitions and once the 2012 definitions.

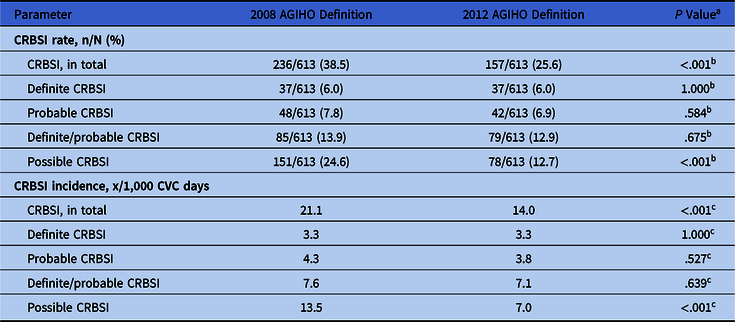

In total, 613 CVCs from cancer patients were analyzed. The patient characteristics were reported elsewhere. Reference Biehl, Huth and Panse8 Our results are summarized in Table 1. According to the 2008 definitions, 236 of 613 CVCs (38.5%) fulfilled criteria for a CRBSI in comparison to 157 of 613 CVCs (25.6%) according to the newer definitions (P < .001). This difference was attributable to documentation of significantly more possCRBSIs in the assessment with the older definitions (151 of 613 [24.6%] vs 78 of 613 [12.7%]; P < .001), but we detected no significant differences for dCRBSIs, pCRBSIs, or dpCRBSIs.

Table 1. Comparison of Epidemiological Parameters of CRBSI According to the 2008 and 2012 AGIHO Criteria

Note. AGIHO, Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology; CRBSI, central venous catheter–related bloodstream infection; CVC, central venous catheter.

a Comparison of the different categories of CRBSI diagnoses with the 2008 and 2012 CRBSI definitions; all P values are 2-sided.

b Fisher exact test.

c χ2 test.

Like the CRBSI rate, the total CRBSI incidence and the incidence of possCRBSIs differed significantly between the assessments with the 2008 and the 2012 definitions (see Table 1 for details).

To measure the interrater reliability (interobserver agreement, precision) between the 2 assessments, we calculated Cohen’s κ. Reference McHugh9 Taking all 613 CVCs into account, there was a strong agreement (κ = .84) between the 2008 and the 2012 definitions. However, this was mostly due to the high proportion of CVCs without any CRBSI diagnosis (311 of 613, 61.5%), which were consistently classified in both the application of the 2008 and the 2012 definitions. Furthermore, all 37 dCRBSIs classified according to the 2008 definitions also met the 2012 definitions for dCRBSIs (κ = 1.00, perfect agreement). As expected, classifications into the group of pCRBSIs and possCRBSIs were less consistent between the 2 definitions. Only 22 of 48 (45.8%) of the older definition of pCRBSIs were also classified as pCRBSIs according to the newer definition (κ = .71, moderate agreement); 26 of 48 (54.2%) were downgraded to possCRBSIs. Analyzing the 85 cases in the combined group of dpCRBSIs according to the 2008 definitions, 59 (69.4%) met the same criteria in the 2012 definitions (κ = .82, strong agreement). Of 151 possCRBSIs in the assessment with the 2008 definitions, only 52 (34.4%) met the criteria for possCRBSIs according to the newer definitions (κ = .47, weak agreement); 79 of 151 (52.3%) were downgraded to cases without a CRBSI diagnosis, whereas 20 of 151 (13.2%) were upgraded to pCRBSIs.

The CRBSI incidence reported in the literature varies strongly, among other factors, depending on the applied CRBSI definition. An accurate CRBSI diagnosis is important for effective and timely treatment and, thus, reduction of further complications. In cancer patients, CRBSI rates are an important end point for supportive care. Reference Tomlinson, Mermel, Ethier, Matlow, Gillmeister and Sung1 Consensus regarding CRBSI definitions is a prerequisite for a meaningful comparison of this important outcome parameter. In a previous study, analyzing the same CVC cohort based on criteria with a microbiological focus yielded a 46% lower CRBSI incidence compared to the incidence analyzed on the basis of a more clinically oriented definition. Reference Tribler, Brandt and Hvistendahl10 Similarly, in our comparison of CRBSI definitions of the former and the updated AGIHO guideline, the CRBSI incidence was ~34% lower using the stricter microbiological criteria (2012 AGIHO definition) compared to the assessment with the 2008 AGIHO definition. However, this discrepancy was only due to the large proportion of possCRBSIs, that is, the more clinically assessed CRBSIs. The interrater reliability regarding dpCRBSIs showed strong agreement, and no significant differences were detected in the dpCRBSIs rate and incidence between the 2008 and 2012 definitions. Based on these findings, strict microbiological definitions seem to yield more consistent epidemiological parameters; they should be used in future studies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.274

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all COAT investigators involved in the conduct of the randomized controlled trial.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

M.J.G.T.V. has served at the speakers’ bureau of Akademie für Infektionsmedizin, Ärztekammer Nordrhein, Astellas Pharma, Basilea, Gilead Sciences, Merck/MSD, Organobalance, and Pfizer, received research funding from 3M, Evoinik, Glycom, Astellas Pharma, DaVolterra, Gilead Sciences, MaaT Pharma, Merck/MSD, Morphochem, Organobalance, and Seres Therapeutics and is a consultant to Alb-Fils Kliniken GmbH, Arderypharm, Astellas Pharma, Ferring, DaVolterra, MaaT Pharma, and Merck/MSD. L.M.B. reports lecture honoraria from Astellas, and MSD and travel grants from 3M and Gilead. E.S. reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.